From Natural Defense to Synthetic Application: Emerging Bacterial Anti-Phage Mechanisms and Their Potential in Industrial Fermentation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Bacteriophages in Industrial Fermentation

2.1. Diversity and Characteristics of Industrial Bacteriophages

2.2. Threats Posed by Bacteriophages to Industrial Fermentation

2.3. Traditional Phage Control Measures

2.4. Development Needs for Broad-Spectrum Phage-Resistant Chassis Cells

3. Research Progress on Bacterial Anti-Phage Systems

3.1. Anti-Phage Methods Based on Blocking Adsorption

3.2. Anti-Phage Mechanisms Based on Inhibiting Replication and Transcription

- (1)

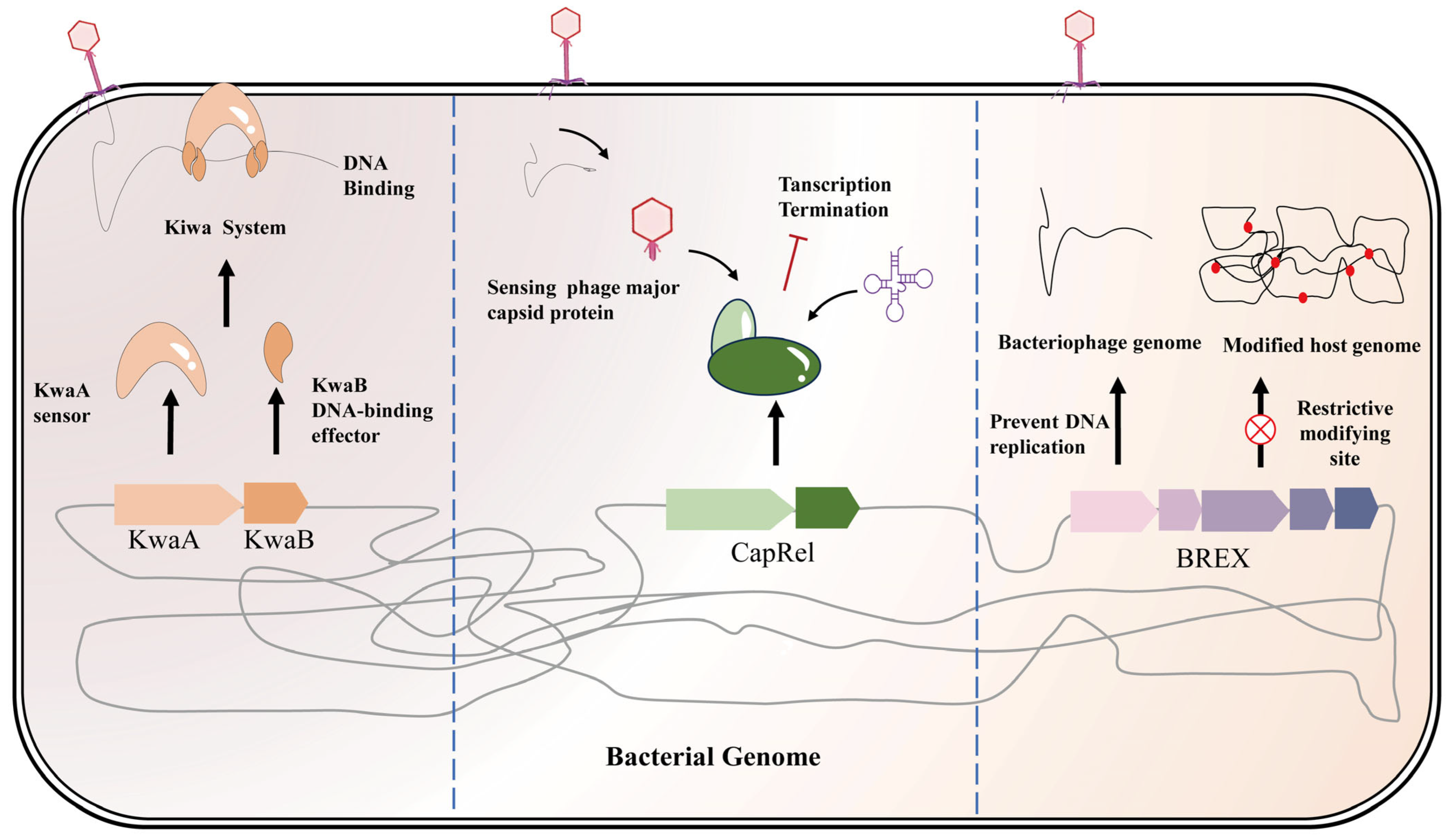

- Repression of Phage Replication Complexes: It was recently discovered that some bacteria produce multi-protein complexes that effectively freeze phage DNA replication at the outset, without cutting the DNA. One example is the Kiwa system, identified in E. coli O55:H7, is a representative example [49]. Kiwa consists of a membrane-anchored sensor protein (KwaA) and a DNA-binding effector protein (KwaB). When a phage adsorbs to the cell surface, KwaA’s periplasmic loop detects this attachment and triggers KwaB to rapidly seize the incoming phage DNA at the inner membrane. By tightly binding the phage DNA, KwaB halts replication initiation and blocks late-gene transcription—without destroying the DNA or killing the host. Because the phage infection is immediately “frozen,” no progeny is produced and the host cell remains alive (Figure 1). This non-suicidal interference is especially valuable in industrial fermentations, as it preserves biomass. However, phages can fight back. Phage T4, for instance, encodes the Gam protein, which imitates a DNA end and binds the KwaB site to inhibit the Kiwa complex. Bacteria in turn reinforce Kiwa with backup: Kiwa loci are often found alongside the host’s RecBCD nuclease [50]. RecBCD will degrade loose phage DNA ends, making it harder for Gam to concurrently block both defenses. Once RecBCD activity removes Gam’s interference, Kiwa can resume its function, thereby restoring robust protection.

- (2)

- Metabolic/Biosynthetic Interference and Toxin-Antitoxin Systems: Many bacterial stress responses to phage involve TA systems that slow or stop cellular metabolism, thereby hindering phage replication. In essence, these act like “mild” abortive infections, damping growth rather than immediately killing the cell. For instance, the CapRel system (a Type II TA) is activated by sensing a phage major capsid protein. When triggered, the antitoxin is degraded and the CapRel toxin is released, which then cleaves specific host tRNAs (Figure 1). This shut-down of protein synthesis halts both host and phage processes, blocking phage production [51,52]. Likewise, the DarTG system (Type IV TA) modifies phage DNA: the DarT toxin ADP-ribosylates the phage genome, preventing normal replication and transcription [53]. Importantly, TA-based defenses are often phage-responsive—they impose their toxic effect only upon detecting a phage signal. For example, T4 infection causes host transcription to cease, which is a cue that activates certain host RNase toxins (like RnlA/RnlB or ToxIN) to start indiscriminately cleaving RNA [54]. These responses may put the host into stasis or even kill it, but crucially, they abort the phage infection before maximal virion production, essentially “trapping” the phage inside a non-growing or dead cell. This curtails phage amplification in the overall population.

- (3)

- Epigenetic Modification and Resource Limitation: Some defenses work by altering DNA chemistry or starving phage processes of resources. The BREX system, for example, modifies the host DNA with unique methylation or phosphorothioate marks [55,56]. Any invading phage DNA lacking these marks is recognized as foreign, and BREX somehow blocks its replication (by an unclear mechanism) without cutting it, drastically reducing phage yield (Figure 1). BREX systems are found in roughly 10% of sequenced bacteria [57]. Similarly, the Dnd system adds phosphorothioate groups to the host genome; phage DNA that is not similarly modified gets selectively attacked by host nucleases, akin to a twist on the restriction-modification concept [58,59]. Bacteria can also slow phage growth by limiting key metabolites. The Gabija defense is illustrative: it has two components, GajA (a nuclease) and GajB (an ATP-binding protein). Under normal nutrient conditions, high nucleotide levels keep GajA inactive. But when a phage infection rapidly depletes the host’s nucleotide pools (dNTPs, NAD+), GajA is unleashed to nick phage DNA, stalling replication forks [60,61]. In this way, Gabija acts as a sensor of phage-induced resource theft: harmless to the host when nutrients are plentiful, but quick to attack phage DNA when the phage is consuming nucleotides. Another multi-gene defense, DISARM (“defense island associated with restriction-modification”), combines several enzymes to concurrently impede phage DNA replication and transcription [62]. Summary: The mechanisms above illustrate how bacteria can stall phage reproduction by means other than direct DNA cleavage—be it through epigenetic discrimination, metabolic booby-traps, or global resource withdrawal. These systems often operate alongside nucleolytic defenses in the same strain, collectively fortifying the cell’s anti-phage arsenal [22,23].

3.3. Anti-Phage Mechanisms Based on Targeted Phage Clearance

- (1)

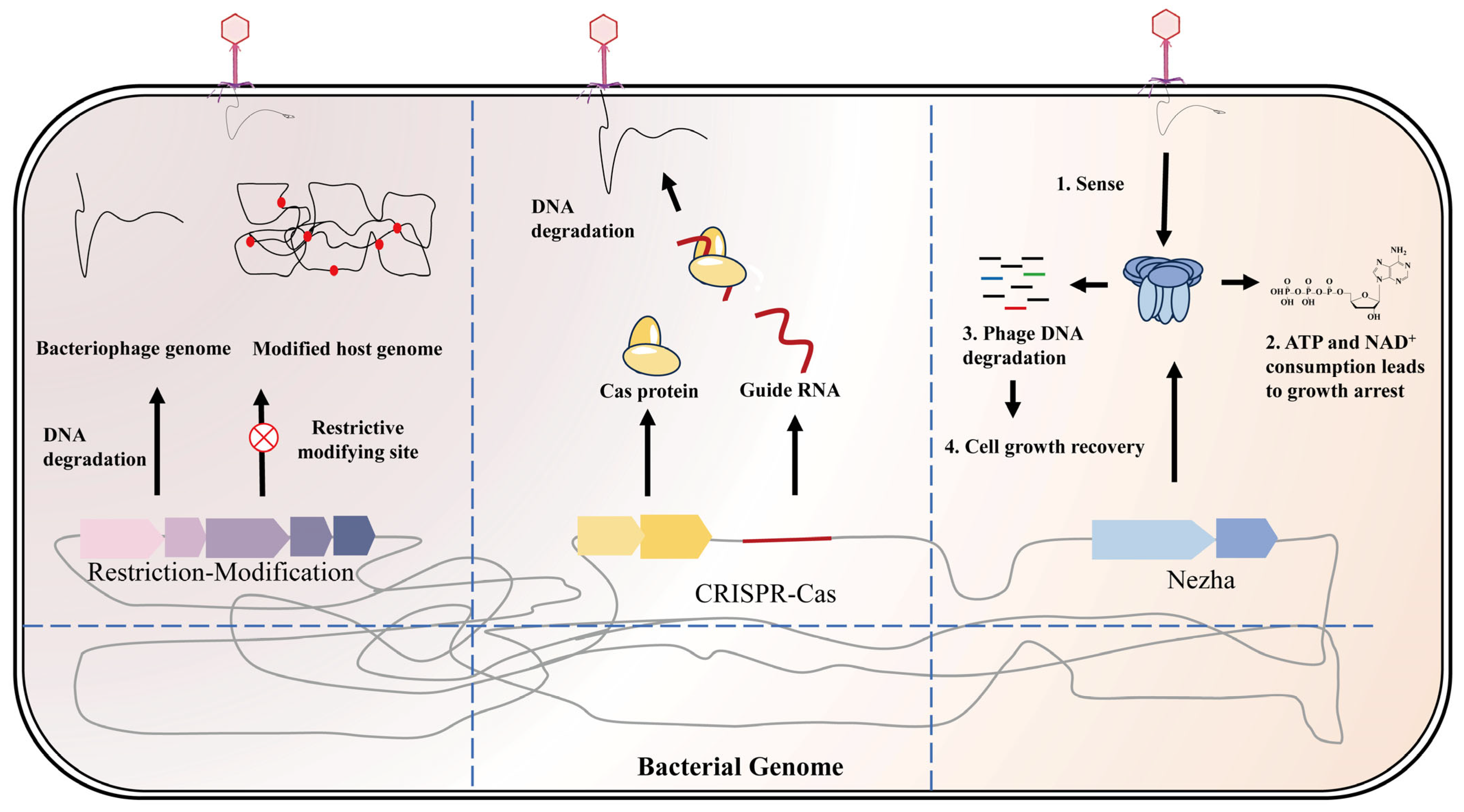

- Restriction-Modification (R-M) Systems: The canonical bacterial defense is the restriction enzyme system, paired with a DNA methylase. The host’s methyltransferase tags its own genome at specific sequences; any incoming DNA lacking those methylation marks is recognized as foreign and cleaved by the restriction endonuclease. R-M systems (especially Types I–IV) are found in ~75% of bacteria [22]. Classic Type II R-M enzymes (e.g., EcoR I) cut at a defined short DNA sequence, while Type I/III systems bind a recognition site but cleave the DNA some distance away. Bacteria have even evolved modification-dependent restriction enzymes to counter phages that chemically modify their DNA (Figure 2). For example, phage T4 glycosylates its 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) bases to evade normal restriction enzymes. E. coli counters with enzymes like PvuRts1I, which specifically recognize 5hmC or its glucosylated form and cut the phage DNA despite its camouflage. In summary, R-M systems distinguish self vs. non-self based on DNA methylation patterns and slice up invader DNA accordingly. They remain a foundational tool (and a go-to engineering strategy) for protecting production strains from phage contamination.

- (2)

- CRISPR-Cas Adaptive Immunity: This system is the bacterial equivalent of a “memory” immune system [63,64,65,66,67]. After surviving a phage attack, a bacterium may integrate snippets of the phage DNA (spacers) into its CRISPR array. Later, if the same phage attacks again, the bacterium transcribes these spacers into CRISPR RNAs (crRNAs) that guide Cas nucleases to the matching phage sequence, cutting the invader’s DNA. There is a wide variety of CRISPR-Cas systems (Figure 2). Generally, Type I and II CRISPR systems target dsDNA. For instance, the well-known Type II-A CRISPR (Cas9) uses a guide RNA to cleave specific phage DNA sequences with surgical precision. Type III CRISPR systems provide a twist: they detect phage RNA transcripts rather than DNA. When a Type III complex binds a phage mRNA, it cleaves that RNA and simultaneously the Cas10 subunit generates a second messenger (cyclic oligoadenylate, cOA) from ATP [68]. This cOA then activates auxiliary nucleases like Csm6/Csx1, which indiscriminately degrade viral RNAs, amplifying the defensive response. In Staphylococcus aureus, for example, the Type III-A system’s Cas10 produces cOA upon sensing target RNA, which activates Csm6 to aggressively degrade viral RNA—greatly enhancing phage clearance. This multi-layered response is conceptually similar to second-messenger cascades in mammalian innate immunity. Interestingly, bacteria sometimes coordinate different CRISPR types: e.g., accessory proteins Csx27/28 in a Type VI system can modulate the cOA pathway of a Type III system, fine-tuning the immune response for efficiency and avoiding excessive self-damage [69,70].

- (3)

- Helicase-Nuclease Complex Systems: A theme emerging from several new discoveries is paired enzymes, a helicase and a nuclease, that work together to demolish phage DNA. The helicase unwinds the phage’s double helix, and the nuclease follows behind, cutting the now-exposed single strands. This one-two punch circumvents many phage DNA protection tricks (like tight packing or secondary structures). For example, the Nezha defense system assembles a large complex of a Sir2-family NADase and a HerA-family helicase [71]. This complex has multiple activities (ATPase, helicase, nuclease) and is thought to sense phage DNA replication, then spring into action: it halts host cell growth and simultaneously chews up the phage genome, but after the threat is eliminated, it switches off to let the cell resume normal function (Figure 2). Notably, even well-known systems have similar components—Type I CRISPR’s Cas3 protein itself is a helicase-nuclease combo. Many recently named defenses also pair unwinding and cutting functions. A concrete example is Shedu: this system, containing a DUF4263-domain protein, serves as an endonuclease that often sits in a larger defense gene cluster, rapidly shredding phage DNA right after injection [72,73]. Another, Pycsar, uses a cyclic nucleotide signal to activate its nuclease component specifically when phage DNA is detected [74]. The proliferation of such multi-enzyme machines underscores how bacteria deploy highly sophisticated molecular tools to ensure any invading phage genome is efficiently unwound and destroyed on the front lines of infection.

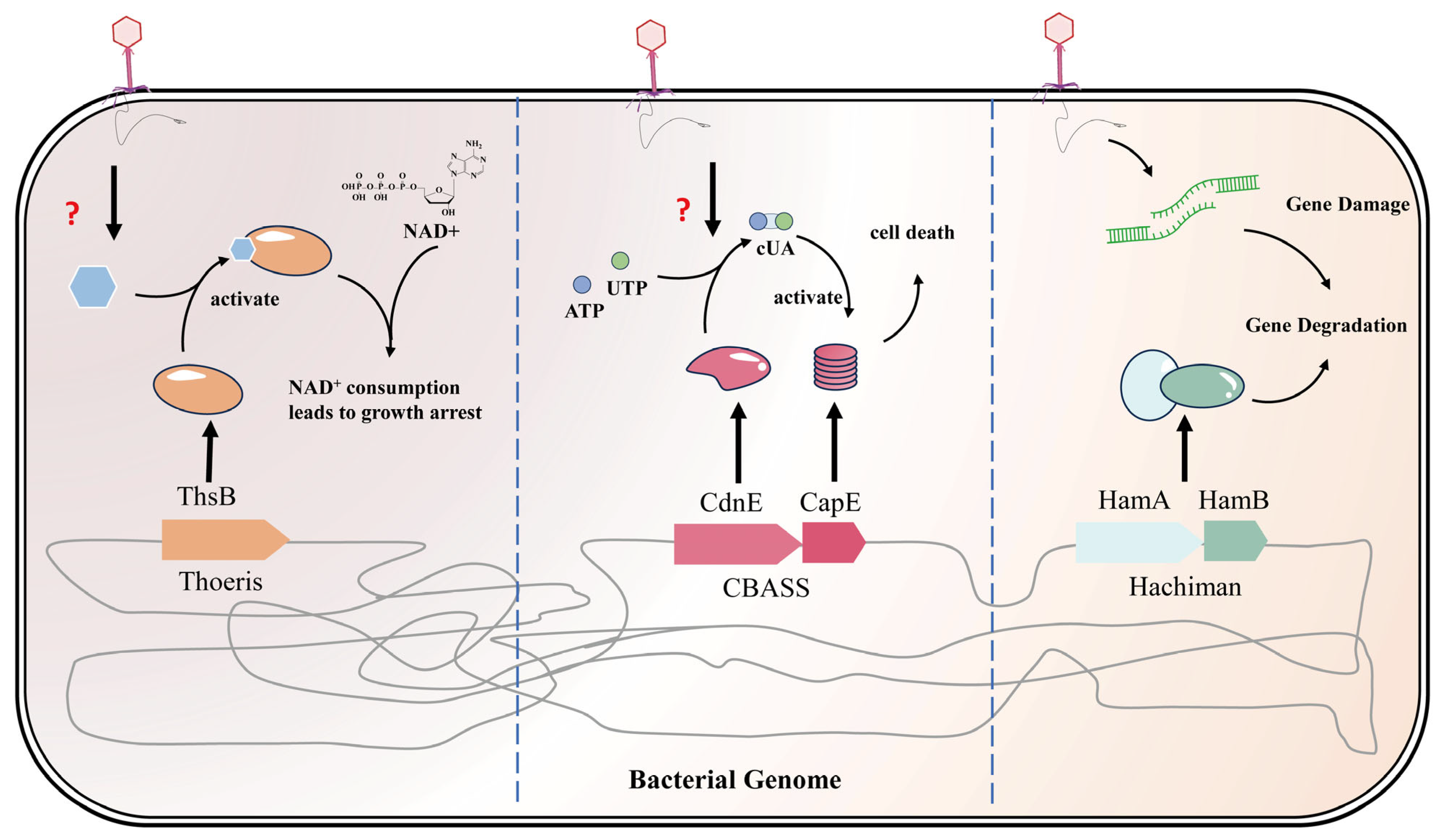

3.4. The Final Line of Defense: Abortive Infection Systems

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kaminski, B.; Paczesny, J. Bacteriophage Challenges in Industrial Processes: A Historical Unveiling and Future Outlook. Pathogens 2024, 13, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, L.; Escobedo, S.; Gutiérrez, D.; Portilla, S.; Martínez, B.; García, P.; Rodríguez, A. Bacteriophages in the Dairy Environment: From Enemies to Allies. Antibiotics 2017, 6, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marco, M.B.; Moineau, S.; Quiberoni, A. Bacteriophages and dairy fermentations. Bacteriophage 2012, 2, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hampton, H.G.; Watson, B.N.J.; Fineran, P.C. The arms race between bacteria and their phage foes. Nature 2020, 577, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.; Mo, Z.R.; Wang, L.R.; Chen, S.; Lee, S.Y. Overcoming Bacteriophage Contamination in Bioprocessing: Strategies and Applications. Small Methods 2025, 9, 2400932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Los, M. Strategies of phage contamination prevention in industry. Open J. Bacteriol. 2020, 4, 20–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Mizushima, S. Roles of Lipopolysaccharide and Outer Membrane Protein OmpC of Escherichia coli K-12 in the Receptor Function for Bacteriophage T4. J. Bacteriol. 1982, 151, 718–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertozzi Silva, J.; Storms, Z.; Sauvageau, D. Host receptors for bacteriophage adsorption. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2016, 363, fnw002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erez, Z.; Steinberger-Levy, I.; Shamir, M.; Doron, S.; Stokar-Avihail, A.; Peleg, Y.; Melamed, S.; Leavitt, A.; Savidor, A.; Albeck, S.; et al. Communication between viruses guides lysis–lysogeny decisions. Nature 2017, 541, 488–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, A.; Sorek, R. The phage-host arms race: Shaping the evolution of microbes. BioEssays 2010, 33, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, X.; Xiao, X.; Mo, Z.; Ge, Y.; Jiang, X.; Huang, R.; Li, M.; Deng, Z.; Chen, S.; Wang, L.; et al. Systematic strategies for developing phage resistant Escherichia coli strains. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevallereau, A.; Pons, B.J.; van Houte, S.; Westra, E.R. Interactions between bacterial and phage communities in natural environments. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 20, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Jiang, H.; Li, C.; Wang, S.; Mi, Z.; An, X.; Chen, J. Sequence characteristics of T4-like bacteriophage IME08 genome termini revealed by high throughput sequencing. Virol. J. 2011, 8, 194. [Google Scholar]

- Orsini, G.; Igonet, S.; Pène, C.; Sclavi, B.; Buckle, M.; Uzan, M.; Kolb, A. Phage T4 early promoters are resistant to inhibition by the anti-sigma factor AsiA. Mol. Microbiol. 2004, 52, 1013–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aframian, N.; Omer Bendori, S.; Hen, T.; Guler, P.; Eldar, A. Expression level of anti-phage defence systems controls a trade-off between protection range and autoimmunity. Nat. Microbiol. 2025, 10, 1954–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortier, L.C.; Bransi, A.; Moineau, S. Genome sequence and global gene expression of Q54, a new phage species linking the 936 and c2 phage species of. J. Bacteriol. 2006, 188, 6101–6114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leprince, A.; Mahillon, J. Phage Adsorption to Gram-Positive Bacteria. Viruses 2023, 15, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyman, P.; Abedon, S.T. Bacteriophage Host Range and Bacterial Resistance. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 2010, 70, 217–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartual, S.G.; Otero, J.M.; Garcia-Doval, C.; Llamas-Saiz, A.L.; Kahn, R.; Fox, G.C.; van Raaij, M.J. Structure of the bacteriophage T4 long tail fiber receptor-binding tip. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 20287–20292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Kim, J.; Kim, M.; Park, Y.; Ryu, S. Development of new strategy combining heat treatment and phage cocktail for post-contamination prevention. Food Res. Int. 2021, 145, 110415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Allah, I.M.; El-Housseiny, G.S.; Al-Agamy, M.H.; Radwan, H.H.; Aboshanab, K.M.; Hassouna, N.A. Statistical optimization of a podoviral anti-MRSA phage CCASU-L10 generated from an under sampled repository: Chicken rinse. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1149848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millman, A.; Melamed, S.; Leavitt, A.; Doron, S.; Bernheim, A.; Hor, J.; Garb, J.; Bechon, N.; Brandis, A.; Lopatina, A.; et al. An expanded arsenal of immune systems that protect bacteria from phages. Cell Host Microbe 2022, 30, 1556–1569.e1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Dai, Z.; Ouyang, Y.; Fu, C.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Yang, K.; Zheng, S.; Wang, W.; Tao, P.; et al. Bacterial Hachiman complex executes DNA cleavage for antiphage defense. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magaziner, S.J.; Salmond, G.P.C. A novel T4- and lambda-based receptor binding protein family for bacteriophage therapy host range engineering. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1010330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H.; Shin, H.; Choi, Y.; Ryu, S. Complete genome sequence analysis of bacterial-flagellum-targeting bacteriophage chi. Arch. Virol. 2013, 158, 2179–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flayhan, A.; Wien, F.; Paternostre, M.; Boulanger, P.; Breyton, C. New insights into pb5, the receptor binding protein of bacteriophage T5, and its interaction with its Escherichia coli receptor FhuA. Biochimie 2012, 94, 1982–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicks, L.M.T.; Vermeulen, W. Bacteriophage-Host Interactions and the Therapeutic Potential of Bacteriophages. Viruses 2024, 16, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohm, K.; Floccari, V.A.; Lutz, V.T.; Nordmann, B.; Mittelstadt, C.; Poehlein, A.; Dragos, A.; Commichau, F.M.; Hertel, R. The Bacillus phage SPbeta and its relatives: A temperate phage model system reveals new strains, species, prophage integration loci, conserved proteins and lysogeny management components. Environ. Microbiol. 2022, 24, 2098–2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yee, L.M.; Matsuoka, S.; Yano, K.; Sadaie, Y.; Asai, K. Inhibitory effect of prophage SPbeta fragments on phage SP10 ribonucleotide reductase function and its multiplication in Bacillus subtilis. Genes. Genet. Syst. 2011, 86, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Ryu, S. Spontaneous and transient defence against bacteriophage by phase-variable glucosylation of O-antigen in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Mol. Microbiol. 2012, 86, 411–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahin, Y.H.; Elwakil, B.H.; Ghareeb, D.A.; Olama, Z.A. Micrococcus lylae MW407006 Pigment: Production, Optimization, Nano-Pigment Synthesis, and Biological Activities. Biology 2022, 11, 1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauerhofer, L.M.; Pappenreiter, P.; Paulik, C.; Seifert, A.H.; Bernacchi, S.; Rittmann, S.K.R. Methods for quantification of growth and productivity in anaerobic microbiology and biotechnology. Folia Microbiol. 2019, 64, 321–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepecka, A.; Okon, A.; Szymanski, P.; Zielinska, D.; Kajak-Siemaszko, K.; Jaworska, D.; Neffe-Skocinska, K.; Sionek, B.; Trzaskowska, M.; Kolozyn-Krajewska, D.; et al. The Use of Unique, Environmental Lactic Acid Bacteria Strains in the Traditional Production of Organic Cheeses from Unpasteurized Cow’s Milk. Molecules 2022, 27, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagerlund, A.; Langsrud, S.; Moretro, T. In-Depth Longitudinal Study of Listeria monocytogenes ST9 Isolates from the Meat Processing Industry: Resolving Diversity and Transmission Patterns Using Whole-Genome Sequencing. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 86, e00579-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, R.; Li, J.; Zeng, P.; Duan, L.; Dong, J.; Ma, Y.; Yang, L. The Application of Membrane Separation Technology in the Pharmaceutical Industry. Membranes 2024, 14, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Zhao, D.; Ye, L.; Zhan, T.; Xiong, B.; Hu, M.; Bi, C.; Zhang, X. A programmable CRISPR/Cas9-based phage defense system for Escherichia coli BL21(DE3). Microb. Cell Fact. 2020, 19, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernheim, A.; Sorek, R. The pan-immune system of bacteria: Antiviral defence as a community resource. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 18, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doron, S.; Melamed, S.; Ofir, G.; Leavitt, A.; Lopatina, A.; Keren, M.; Amitai, G.; Sorek, R. Systematic discovery of antiphage defense systems in the microbial pangenome. Science 2018, 359, eaar4120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belalov, I.S.; Sokolov, A.A.; Letarov, A.V. Diversity-Generating Retroelements in Prokaryotic Immunity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassallo, C.N.; Doering, C.R.; Littlehale, M.L.; Teodoro, G.I.C.; Laub, M.T. A functional selection reveals previously undetected anti-phage defence systems in the E. coli pangenome. Nat. Microbiol. 2022, 7, 1568–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; You, J.; Pan, X.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, W.; Rao, Z. Genomic and biological insights of bacteriophages JNUWH1 and JNUWD in the arms race against bacterial resistance. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1407039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Huang, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wu, Q.; Xue, L.; Wang, J.; Ding, Y. Recent advances in phage defense systems and potential overcoming strategies. Biotechnol. Adv. 2023, 65, 108152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, N.T.; Hryckowian, A.J.; Merrill, B.D.; Fuentes, J.J.; Gardner, J.O.; Glowacki, R.W.P.; Singh, S.; Crawford, R.D.; Snitkin, E.S.; Sonnenburg, J.L.; et al. Phase-variable capsular polysaccharides and lipoproteins modify bacteriophage susceptibility in Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron. Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5, 1170–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Huang, L.; Yang, Y.; Xiang, Y.; Liu, J. Essential phage component induces resistance of bacterial community. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadp5057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Perez, J.; Otero, J.; Sanchez-Osuna, M.; Erill, I.; Cortes, P.; Llagostera, M. Impact of mutagenesis and lateral gene transfer processes in bacterial susceptibility to phage in food biocontrol and phage therapy. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1266685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venturini, C.; Petrovic Fabijan, A.; Fajardo Lubian, A.; Barbirz, S.; Iredell, J. Biological foundations of successful bacteriophage therapy. EMBO Mol. Med. 2022, 14, e12435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.C.; Laderman, E.; Huiting, E.; Zhang, C.; Davidson, A.; Bondy-Denomy, J. Core defense hotspots within Pseudomonas aeruginosa are a consistent and rich source of anti-phage defense systems. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, 4995–5005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hochhauser, D.; Millman, A.; Sorek, R. The defense island repertoire of the Escherichia coli pan-genome. PLoS Genet. 2023, 19, e1010694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Todeschini, T.C.; Wu, Y.; Kogay, R.; Naji, A.; Cardenas Rodriguez, J.; Mondi, R.; Kaganovich, D.; Taylor, D.W.; Bravo, J.P.K.; et al. Kiwa is a membrane-embedded defense supercomplex activated at phage attachment sites. Cell 2025, 188, 5862–5877.e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.; Wilkinson, M.; Chaban, Y.; Wigley, D.B. A conformational switch in response to Chi converts RecBCD from phage destruction to DNA repair. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2020, 27, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Tamman, H.; Coppieters ’t Wallant, K.; Kurata, T.; LeRoux, M.; Srikant, S.; Brodiazhenko, T.; Cepauskas, A.; Talavera, A.; Martens, C.; et al. Direct activation of a bacterial innate immune system by a viral capsid protein. Nature 2022, 612, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokar-Avihail, A.; Fedorenko, T.; Hör, J.; Garb, J.; Leavitt, A.; Millman, A.; Shulman, G.; Wojtania, N.; Melamed, S.; Amitai, G.; et al. Discovery of phage determinants that confer sensitivity to bacterial immune systems. Cell 2023, 186, 1863–1876.e1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeRoux, M.; Srikant, S.; Teodoro, G.I.C.; Zhang, T.; Littlehale, M.L.; Doron, S.; Badiee, M.; Leung, A.K.L.; Sorek, R.; Laub, M.T. The DarTG toxin-antitoxin system provides phage defence by ADP-ribosylating viral DNA. Nat. Microbiol. 2022, 7, 1028–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, H.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, X.; Dai, L.; Tong, A.; Tang, D.; Chen, Q.; Yu, Y. A toxin-antitoxin system provides phage defense via DNA damage and repair. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhushan, K. BacteRiophage EXclusion (BREX): A novel anti-phage mechanism in the arsenal of bacterial defense system. J. Cell. Physiol. 2017, 233, 771–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordeeva, J.; Morozova, N.; Sierro, N.; Isaev, A.; Sinkunas, T.; Tsvetkova, K.; Matlashov, M.; Truncaitė, L.; Morgan, R.D.; Ivanov, N.V.; et al. BREX system ofEscherichia colidistinguishes self from non-self by methylation of a specific DNA site. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldfarb, T.; Sberro, H.; Weinstock, E.; Cohen, O.; Doron, S.; Charpak-Amikam, Y.; Afik, S.; Ofir, G.; Sorek, R. BREX is a novel phage resistance system widespread in microbial genomes. EMBO J. 2014, 34, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Guan, S.; Quimby, A.; Cohen-Karni, D.; Pradhan, S.; Wilson, G.; Roberts, R.J.; Zhu, Z.; Zheng, Y. Comparative characterization of the PvuRts1I family of restriction enzymes and their application in mapping genomic 5-hydroxymethylcytosine. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, 9294–9305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, S.; Chen, C.; Huang, W.; He, Y.; Du, X.; Wang, Y.; Ou, H.; Deng, Z.; Xu, C.; Jiang, L.; et al. A widespread phage-encoded kinase enables evasion of multiple host antiphage defence systems. Nat. Microbiol. 2024, 9, 3226–3239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, R.; Huang, F.; Wu, H.; Lu, X.; Yan, Y.; Yu, B.; Wang, X.; Zhu, B. A nucleotide-sensing endonuclease from the Gabija bacterial defense system. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, 5216–5229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.A.; Wilkinson, M.E.; Strecker, J.; Makarova, K.S.; Macrae, R.K.; Koonin, E.V.; Zhang, F. Prokaryotic innate immunity through pattern recognition of conserved viral proteins. Science 2022, 377, eabm4096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofir, G.; Melamed, S.; Sberro, H.; Mukamel, Z.; Silverman, S.; Yaakov, G.; Doron, S.; Sorek, R. DISARM is a widespread bacterial defence system with broad anti-phage activities. Nat. Microbiol. 2017, 3, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.i.; Sun, B.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, Y.u.; Yang, S. A modified pCas/pTargetF system for CRISPR-Cas9-assisted genome editing in Escherichia coli. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2021, 53, 620–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amitai, G.; Sorek, R. CRISPR–Cas adaptation: Insights into the mechanism of action. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 14, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouillon, C.; Schneberger, N.; Chi, H.; Blumenstock, K.; Da Vela, S.; Ackermann, K.; Moecking, J.; Peter, M.F.; Boenigk, W.; Seifert, R.; et al. Antiviral signalling by a cyclic nucleotide activated CRISPR protease. Nature 2022, 614, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasiunas, G.; Sinkunas, T.; Siksnys, V. Molecular mechanisms of CRISPR-mediated microbial immunity. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2013, 71, 449–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.P.; Dai, L.; Dong, J.H.; Chen, C.; Zhu, J.G.; Rao, V.B.; Tao, P. Covalent Modifications of the Bacteriophage Genome Confer a Degree of Resistance to Bacterial CRISPR Systems. J. Virol. 2020, 94, e01630-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niewoehner, O.; Garcia-Doval, C.; Rostøl, J.T.; Berk, C.; Schwede, F.; Bigler, L.; Hall, J.; Marraffini, L.A.; Jinek, M. Type III CRISPR–Cas systems produce cyclic oligoadenylate second messengers. Nature 2017, 548, 543–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKitterick, A.C.; LeGault, K.N.; Angermeyer, A.; Alam, M.; Seed, K.D. Competition between mobile genetic elements drives optimization of a phage-encoded CRISPR-Cas system: Insights from a natural arms race. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2019, 374, 20180089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, M.; Li, J. The evolving CRISPR technology. Protein Cell 2019, 10, 783–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, D.; Chen, Y.; Chen, H.; Jia, T.; Chen, Q.; Yu, Y. Multiple enzymatic activities of a Sir2-HerA system cooperate for anti-phage defense. Mol. Cell 2023, 83, 4600–4613.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.J.; Li, H.; Deep, A.; Enustun, E.; Zhang, D.P.; Corbett, K.D. Bacterial Shedu immune nucleases share a common enzymatic core regulated by diverse sensor domains. Mol. Cell 2025, 85, 523–536.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeff, L.; Walter, A.; Rosalen, G.T.; Jinek, M. DNA end sensing and cleavage by the Shedu anti-phage defense system. Cell 2025, 188, 721–733 e717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, M.H.; Chen, C.J.; Yang, C.S.; Wang, Y.C.; Chen, Y. Structural and functional characterization of cyclic pyrimidine-regulated anti-phage system. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampton, H.G.; Jackson, S.A.; Fagerlund, R.D.; Vogel, A.I.M.; Dy, R.L.; Blower, T.R.; Fineran, P.C. AbiEi Binds Cooperatively to the Type IV abiE Toxin-Antitoxin Operator Via a Positively-Charged Surface and Causes DNA Bending and Negative Autoregulation. J. Mol. Biol. 2018, 430, 1141–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Rodriguez, G.; Perez, A.T.; Konijnenberg, A.; Sobott, F.; Michiels, J.; Loris, R. The RnlA-RnlB toxin-antitoxin complex: Production, characterization and crystallization. Acta Crystallogr. F 2020, 76, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naka, K.; Qi, D.; Yonesaki, T.; Otsuka, Y. RnlB Antitoxin of the RnlA-RnlB Toxin-Antitoxin Module Requires RNase HI for Inhibition of RnlA Toxin Activity. Toxins 2017, 9, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durmaz, E.; Klaenhammer, T.R. Abortive phage resistance mechanism AbiZ speeds the lysis clock to cause premature lysis of phage-infected. J. Bacteriol. 2007, 189, 1417–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haudiquet, M.; Chakravarti, A.; Zhang, Z.; Ramirez, J.L.; Herrero del Valle, A.; Olinares, P.D.B.; Lavenir, R.; Ahmed, M.A.; de la Cruz, M.J.; Chait, B.T.; et al. Structural basis for Lamassu-based antiviral immunity and its evolution from DNA repair machinery. bioRxiv 2025. bioRxiv:2025.2004.2002.646746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, Z.; Lang, H.; Fu, W.; Gao, Y.; Yin, S.; Sun, P.; Li, Z.; Huang, J.; Liu, S.; et al. Cyclic-dinucleotide-induced filamentous assembly of phospholipases governs broad CBASS immunity. Cell 2025, 188, 3744–3756.e3716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Q.S.; Richey, S.T.; Ur, S.N.; Ye, Q.Z.; Lau, R.K.; Corbett, K.D. Structure and activity of a bacterial defense-associated 3′-5′ exonuclease. Protein Sci. 2022, 31, e4374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabonis, D.; Avraham, C.; Chang, R.B.; Lu, A.; Herbst, E.; Silanskas, A.; Vilutis, D.; Leavitt, A.; Yirmiya, E.; Toyoda, H.C.; et al. TIR domains produce histidine-ADPR as an immune signal in bacteria. Nature 2025, 642, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, J.; Wu, W.; Ke, S.; Zhou, Z.; Xia, S.; Chen, J.; Zhu, R.; Hou, Y.; Makanyire, T.; Shan, X.; et al. Molecular mechanisms of CBASS phospholipase effector CapV mediated membrane disruption. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 8611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swarts, D.C.; Jore, M.M.; Westra, E.R.; Zhu, Y.; Janssen, J.H.; Snijders, A.P.; Wang, Y.; Patel, D.J.; Berenguer, J.; Brouns, S.J.J.; et al. DNA-guided DNA interference by a prokaryotic Argonaute. Nature 2014, 507, 258–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ofir, G.; Herbst, E.; Baroz, M.; Cohen, D.; Millman, A.; Doron, S.; Tal, N.; Malheiro, D.B.A.; Malitsky, S.; Amitai, G.; et al. Antiviral activity of bacterial TIR domains via immune signalling molecules. Nature 2021, 600, 116–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yirmiya, E.; Leavitt, A.; Lu, A.L.; Ragucci, A.E.; Avraham, C.; Osterman, I.; Garb, J.; Antine, S.P.; Mooney, S.E.; Hobbs, S.J.; et al. Phages overcome bacterial immunity via diverse anti-defence proteins. Nature 2024, 625, 352–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huiting, E.; Bondy-Denomy, J. A single bacterial enzyme i(NHI)bits phage DNA replication. Cell Host Microbe 2022, 30, 417–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temin, H.M. Reverse transcriptases. Retrons in bacteria. Nature 1989, 339, 254–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millman, A.; Bernheim, A.; Stokar-Avihail, A.; Fedorenko, T.; Voichek, M.; Leavitt, A.; Oppenheimer-Shaanan, Y.; Sorek, R. Bacterial Retrons Function In Anti-Phage Defense. Cell 2020, 183, 1551–1561.e1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.D.; Popp, P.F.; Hughes, T.C.D.; Roa-Eguiara, A.; Rutbeek, N.R.; Martin, F.J.O.; Hendriks, I.A.; Payne, L.J.; Yan, Y.M.; Humolli, D.; et al. Structure and mechanism of the Zorya anti-phage defence system. Nature 2025, 639, 1093–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Bacteriophage | Classify | Host | Receptor |

|---|---|---|---|

| T4 | Myoviridae | E. coli | LPS/OmpC |

| T7 | Podoviridae | E. coli | LPS |

| T5 | Siphoviridae | E. coli | FhuA |

| T1 | Siphoviridae | E. coli | FhuA/TonBb |

| T2 | Myoviridae | E. coli | OmpF/lipopolysaccharide/FadL |

| Lambda | Siphoviridae | E. coli | LamB |

| SPP1 | Siphoviridae | Bacillus subtilis | Polyglycerol phosphate on the glucose group of WTA YueB |

| φ29 | Podoviridae | B. subtilis | WTA |

| p2 | Siphoviridae | Lactococcus lactis | Cell wall carbohydrates/ The phosphogluconate group on the membrane |

| SPC35 | Siphoviridae | Salmonella sp. | BtuB/O12-antigen |

| DT1 | Siphoviridae | S. thermophilus | Cell wall polysaccharides |

| 2972 | Siphoviridae | S. thermophilus | Cell wall polysaccharides |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, H.; You, J.; Li, G.; Rao, Z.; Zhang, X. From Natural Defense to Synthetic Application: Emerging Bacterial Anti-Phage Mechanisms and Their Potential in Industrial Fermentation. Fermentation 2026, 12, 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation12010017

Zhang H, You J, Li G, Rao Z, Zhang X. From Natural Defense to Synthetic Application: Emerging Bacterial Anti-Phage Mechanisms and Their Potential in Industrial Fermentation. Fermentation. 2026; 12(1):17. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation12010017

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Hengwei, Jiajia You, Guomin Li, Zhiming Rao, and Xian Zhang. 2026. "From Natural Defense to Synthetic Application: Emerging Bacterial Anti-Phage Mechanisms and Their Potential in Industrial Fermentation" Fermentation 12, no. 1: 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation12010017

APA StyleZhang, H., You, J., Li, G., Rao, Z., & Zhang, X. (2026). From Natural Defense to Synthetic Application: Emerging Bacterial Anti-Phage Mechanisms and Their Potential in Industrial Fermentation. Fermentation, 12(1), 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation12010017