Combined Effect of Sonication and Electron Beam Irradiation on the Photocatalytic Organic Dye Decomposition Efficiency of Graphitic Carbon Nitride

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of g-C3N4

2.2. Sonication and Electron Beam Irradiation

2.3. Characterization

2.4. Photocatalytic Decomposition of Organic Dye

3. Results and Discussion

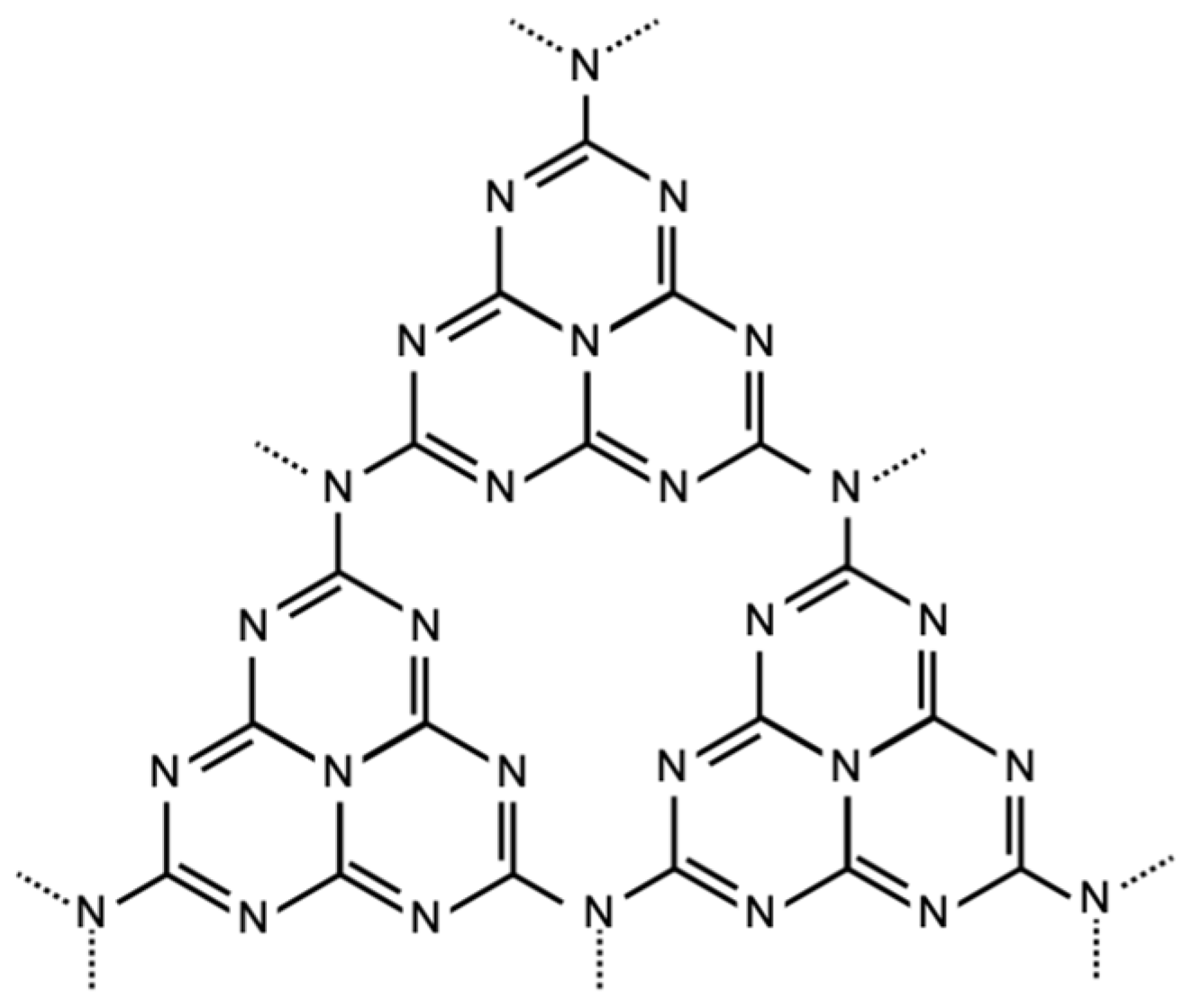

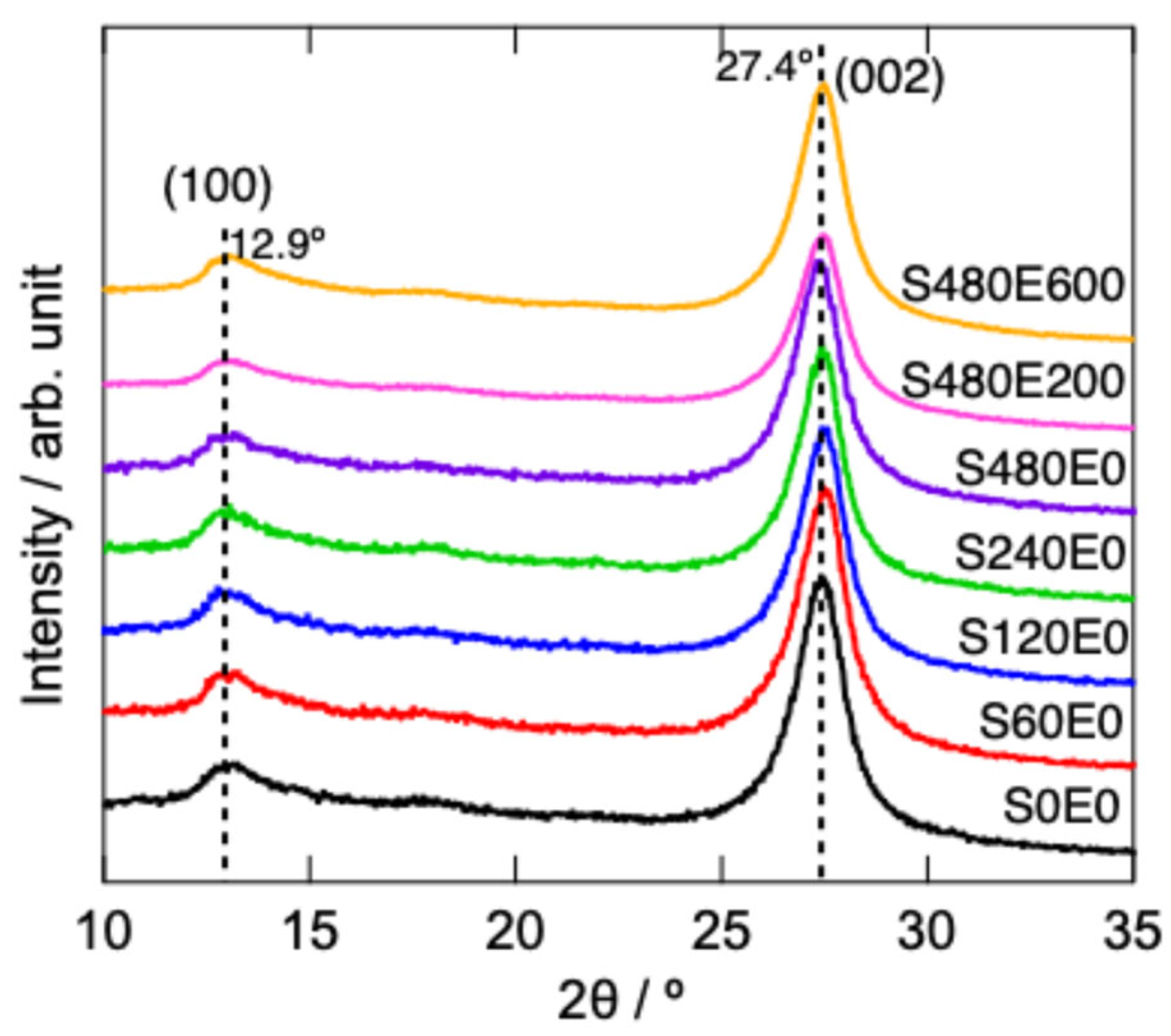

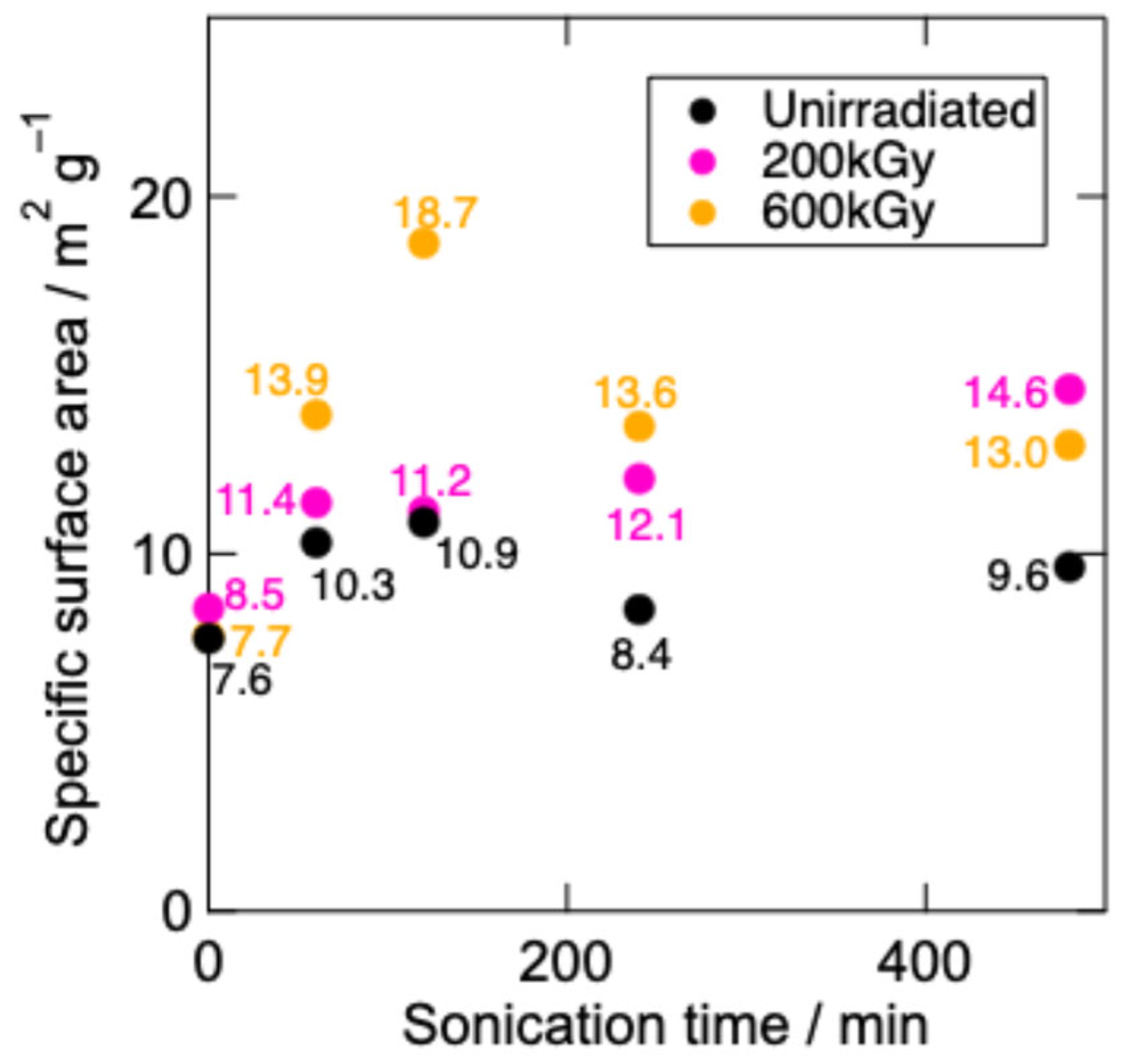

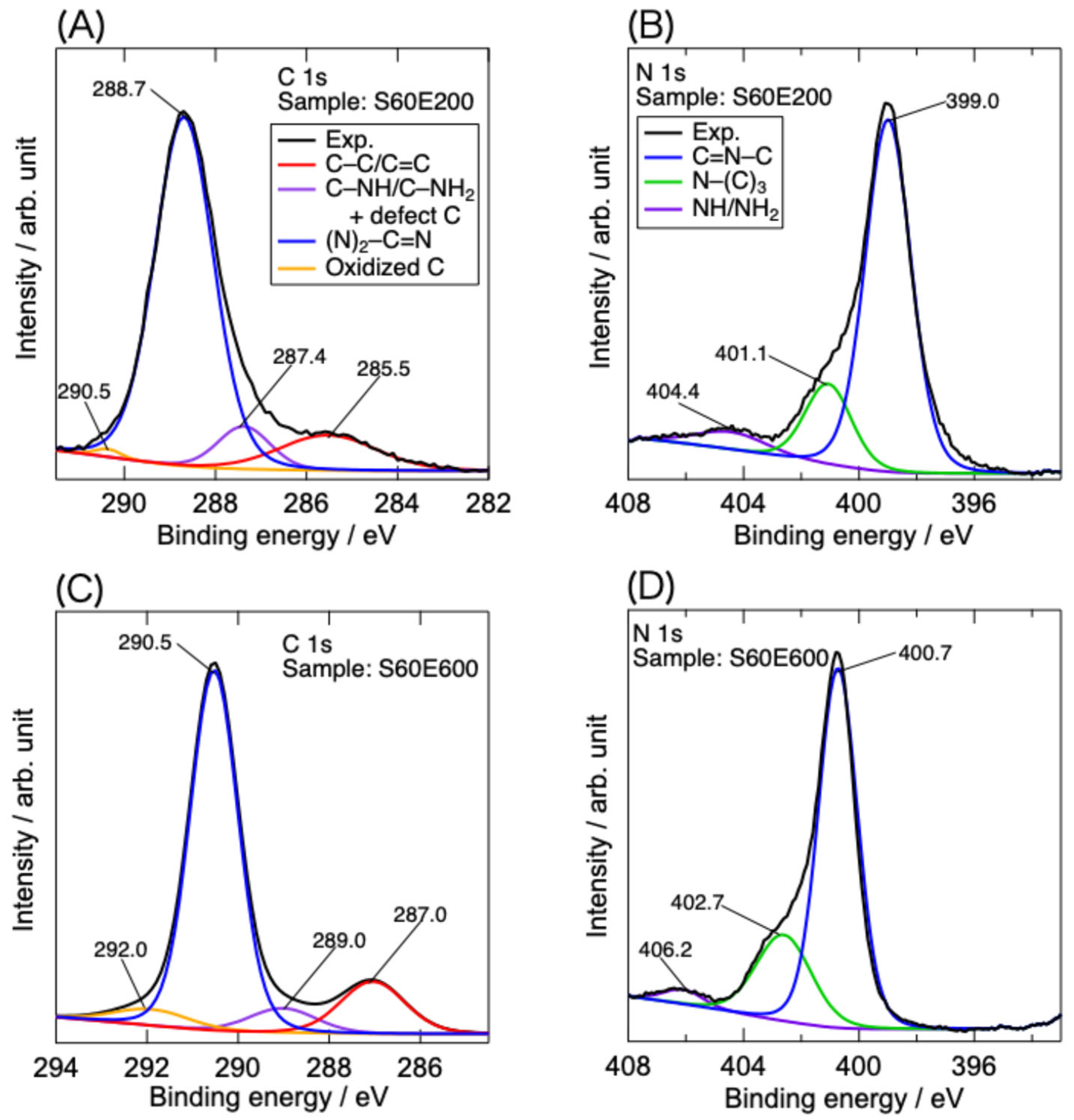

3.1. Characterization of g-C3N4

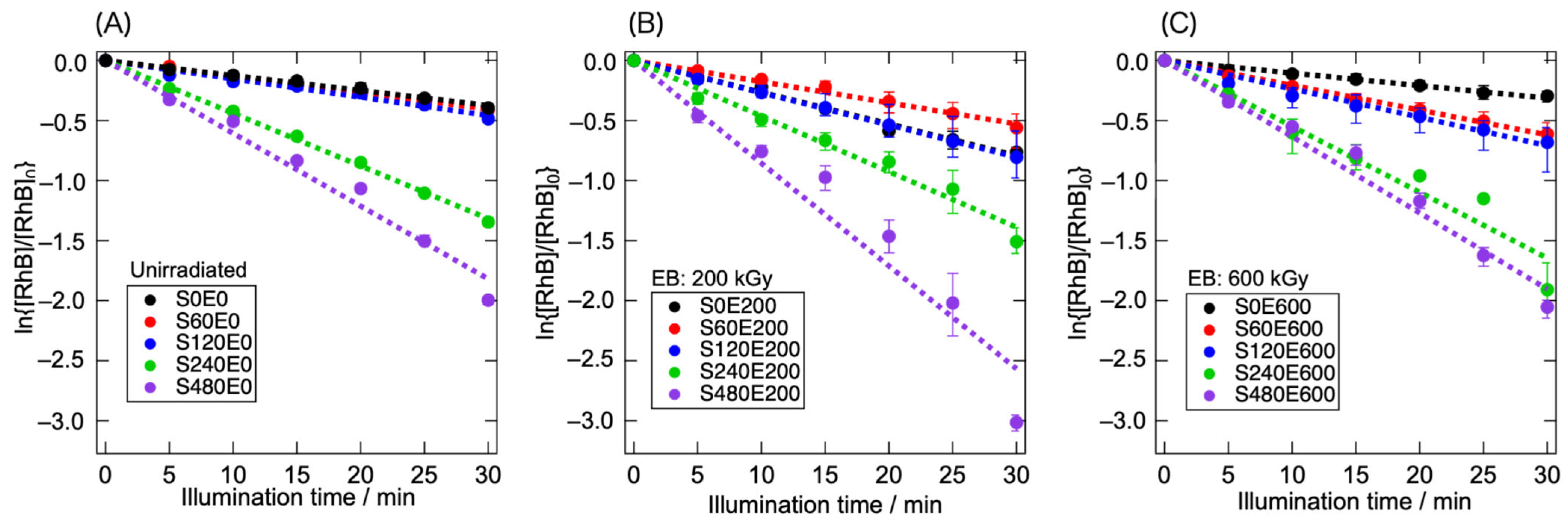

3.2. Photocatalytic RhB Decomposition Using Treated g-C3N4

4. Conclusions

- Low-dose EB irradiation further improves the reaction efficiency of sonicated g-C3N4, as it does that of g-C3N4 that is not sonicated.

- Higher-dose EB irradiation did not markedly increase the reaction efficiency compared to that of unirradiated g-C3N4 despite its larger specific surface area.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, Z.; Wang, J.; Iqbal, W.; Shi, M.; Yang, L.; Chang, N.; Qin, C. Morphology-effects of four different dimensional graphitic carbon nitrides on photocatalytic performance of dye degradation, water oxidation and splitting. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2023, 173, 111109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wang, W.; Hu, W.; Xu, S.; Gao, C.; Li, X. Nitrogen vacancy/oxygen dopants designed nanoscale hollow tubular g-C3N4 with excellent photocatalytic hydrogen evolution and photodegradation. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2023, 180, 111477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Wang, Y.; Nga, T.T.T.; Zhang, J.; Wang, R.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, D.; Dong, C.-L.; Shen, S. Electron-rich pyrimidine rings enabling crystalline carbon nitride for high-efficiency photocatalytic hydrogen evolution coupled with benzyl alcohol selective oxidation. EES Catal. 2023, 1, 552–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Shi, W.; Lu, J.; Shi, Y.; Guo, F.; Kang, Z. Dual-channels separated mechanism of photo-generated charges over semiconductor photocatalyst for hydrogen evolution: Interfacial charge transfer and transport dynamics insight. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 454, 140442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Liu, H.; Sun, C.; Wu, L.; Jiao, F. Precise Defect Engineering with Ultrathin Porous Frameworks on g-C3N4 for Synergetic Boosted Photocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2024, 63, 2665–2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, U.; Pal, A. Defect engineered mesoporous 2D graphitic carbon nitride nanosheet photocatalyst for rhodamine B degradation under LED light illumination. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2020, 397, 112582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Yang, D.; Ding, F.; An, K.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, W.; Jiang, Z. One-pot fabrication of porous nitrogen-deficient g-C3N4 with superior photocatalytic performance. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2020, 400, 112729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Fang, W.-X.; Wang, J.-C.; Qiao, X.; Wang, B.; Guo, X. pH-controlled mechanism of photocatalytic RhB degradation over g-C3N4 under sunlight irradiation. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2021, 20, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Li, X.; Song, P.; Ma, F. Porous graphitic carbon nitride nanosheets for photocatalytic degradation of formaldehyde gas. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2021, 762, 138132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Zhou, P.; Zhang, L.; Zhong, Y.; Sui, X.; Wang, B.; Ma, Y.; Feng, X.; Xu, H.; Mao, Z. g-C3N4 nanosheets exfoliated by green wet ball milling process for photodegradation of organic pollutants. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2021, 766, 138335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, D.A.; Pham, C.T.N.; Ngoc, T.N.; Phi, H.N.; Ta, Q.T.H.; Truong, D.H.; Nguyen, V.T.; Luc, H.H.; Nguyen, L.T.; Dao, N.N.; et al. One-step synthesis of oxygen doped g-C3N4 for enhanced visible-light photodegradation of Rhodamine B. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2021, 151, 109900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Tsai, W.-F.; Wei, W.-H.; Lin, K.-Y.A.; Liu, M.-T.; Nakagawa, K. Hydroxylation and sodium intercalation on g-C3N4 for photocatalytic removal of gaseous formaldehyde. Carbon 2021, 175, 467–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, A.G.; Hussain, M.Z.; Hammond, N.; Luca, S.V.; Fischer, R.A.; Minceva, M. Synthesis of Highly Active Doped Graphitic Carbon Nitride using Acid-Functionalized Precursors for Efficient Adsorption and Photodegradation of Endocrine-Disrupting Compounds. ChemistrySelect 2022, 7, e202201909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamble, G.; Ganai, A.M.; Lakshmi, D.V.; Rao, N.N.; Rajarikam, N.; Rao, P.V. Impact of pyrolysis temperature on physicochemical properties of carbon nitride photocatalyst. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 2023, 38, 055020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefa, S.; Zografaki, M.; Dimitropouros, M.; Paterakis, G.; Galiotis, C.; Sangeetha, P.; Kiriakidis, G.; Konsolakis, M.; Binas, V. High surface area g-C3N4 nanosheets as superior solar-light photocatalyst for the degradation of parabens. Appl. Phys. A 2023, 129, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Molina, Á.; Pastrana-Martínez, L.M.; Morales-Torres, S.; Maldonado-Hódar, F.J. Photodegradation of cytostatic drugs by g-C3N4; Synthesis, properties and performance fitted by selecting the appropriate precursor. Catal. Today 2023, 418, 114068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, V.A.; Huu, H.T.; Ngo, H.N.T.; Ngo, N.N.; Thi, L.N.; Phan, T.T.T.; Nguyen, L.T.; Nguyen, T.L.; Luc, H.H.; Le, V.T.; et al. Magnesiothermic reduction synthesis of N-deficient g-C3N4 with enhanced photocatalytic performance under visible light. Chem. Phys. 2023, 575, 112061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, D.; Kim, S.; Fujitsuka, M.; Majima, T. Defects rich g-C3N4 with mesoporous structure for efficient photocatalytic H2 production under visible light irradiation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2018, 238, 638–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Cheng, L.; Wang, Y.; Miao, Y.; Ding, G.; Jiao, Z. Two physical strategies to reinforce a nonmetallic photocatalyst, g-C3N4: Vacuum heating and electron beam irradiation. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 14002–14008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picho-Chillán, G.; Dante, R.C.; Muños-Bisesti, F.; Martín-Ramos, P.; Chamorro-Posada, P.; Vargas-Jentzsch, P.; Sánchez-Arévalo, F.M.; Sandoval-Pauker, C.; Rutto, D. Photodegradation of Direct Blue 1 azo dye by polymeric carbon nitride irradiated with accelerated electrons. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2019, 237, 121878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, R.G.; Ta, H.Q.; Yan, X.; Bachmatiuk, A.; Praus, P.; Mamakhel, A.; Iversen, B.B.; Su, R.; Gemming, T.; Rümmeli, M.H. Tailoring the stoichiometry of C3N4 nanosheets under electron beam irradiation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2021, 23, 4747–4756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, L.; Paramanik, L.; Choi, D.; Yoo, S.H. Advancing photocatalytic performance for enhanced visible-light-driven H2 evolution and Cr(VI) reduction of g-C3N4 through defect engineering via electron beam irradiation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2025, 685, 161996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harako, A.; Shimoda, S.; Suzuki, K.; Fukuoka, A.; Takada, T. Effects of the electron-beam-induced modification of g-C3N4 on its performance in photocatalytic organic dye decomposition. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2023, 813, 140320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Cao, Y.; Wang, H.; Yu, H.; Peng, F.; Zou, H.; Liu, Z. Revealing active-site structure of porous nitrogen-defected carbon nitride for highly effective photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 373, 687–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Gao, B.; Dou, M.; Huang, X.; Ma, Z. A porous g-C3N4 nanosheets containing nitrogen defects for enhanced photocatalytic removal meropenem: Mechanism, degradation pathway, and DFT calculation. Environ. Res. 2020, 184, 109339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, D.; Jia, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, J.; Meng, F.; Wang, D.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, Z. Facile synthesis of distinctive nitrogen defect-regulated g-C3N4 for efficient photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2024, 142, 110816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Iwasa, N.; Fujita, S.; Koizumi, H.; Yamaguchi, M.; Shimada, T. Porous graphitic carbon nitride nanoplates obtained by a combined exfoliation strategy for enhanced visible light photocatalytic activity. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 499, 143901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Yanase, T.; Iwasa, N.; Koizumi, H.; Mukai, S.; Iwamura, S.; Nagahama, T.; Shimada, T. Sugar-assisted mechanochemical exfoliation of graphitic carbon nitride for enhanced visible-light photocatalytic performance. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 8444–8455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Song, C.; Kou, M.; Wang, Y.; Deng, Y.; Shimada, T.; Ye, L. Fabrication of ultra-thin g-C3N4 nanoplates for efficient visible-light photocatalytic H2O2 production via two-electron oxygen reduction. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 425, 130615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Gong, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhan, L.; Ma, L.; Fang, Z.; Vajtai, R.; Wang, X.; Ajayan, P.M. Exfoliated Graphitic Carbon Nitride Nanosheets as Efficient Catalysts for Hydrogen Evolution Under Visible Light. Adv. Mater. 2013, 25, 2452–2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, X.; Xu, H.; Xu, Y.; Yan, J.; Xia, J.; Xu, L.; Song, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Li, H. Exfoliated graphene-like carbon nitride in organic solvents: Enhanced photocatalytic activity and highly selective and sensitive sensor for the detection of trace amounts of Cu2+. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 2563–2570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairley, N.; Fernandez, V.; Richard-Plouet, M.; Guillot-Deudon, C.; Walton, J.; Smith, E.; Flahaut, D.; Greiner, M.; Biesinger, M.; Tougaard, S.; et al. Systematic and collaborative approach to problem solving using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. Appl. Surf. Sci. Adv. 2021, 5, 100112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunauer, S.; Emmett, P.H.; Teller, E. Adsorption of Gases in Multimolecular Layers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1938, 60, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fudouzi, H.; Egashira, M.; Shinya, N. Formation of electrified images using electron and ion beams. J. Electrostat. 1997, 42, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatarintsev, A.A.; Zykova, E.Y.; Ieshkin, A.E.; Orikovsaya, N.G.; Rau, E.I. Electrization of the Quartz Glass Surface by Electron Beams. Phys. Solid State 2023, 65, 1236–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghobashy, M.M.; Sharshir, A.I.; Zaghlool, R.A.; Mohamed, F. Investigating the impact of electron beam irradiation on electrical, magnetic, and optical properties of XLPE/Co3O4 nanocomposites. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 4829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, R.; Dou, H.; Chen, L.; Zheng, S.; Zhang, Y. Graphitic carbon nitride with S and O codoping for enhanced visible light photocatalytic performance. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 15842–15850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhmood, T.; Xia, M.; Lei, W.; Wang, F.; Mahmood, A. Fe-ZrO2 imbedded graphene like carbon nitride for acarbose (ACB) photo-degradation intermediate study. Adv. Powder Technol. 2018, 29, 3233–3240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Harako, A.; Shimoda, S.; Suzuki, K.; Fukuoka, A.; Takada, T. Combined Effect of Sonication and Electron Beam Irradiation on the Photocatalytic Organic Dye Decomposition Efficiency of Graphitic Carbon Nitride. C 2025, 11, 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/c11040091

Harako A, Shimoda S, Suzuki K, Fukuoka A, Takada T. Combined Effect of Sonication and Electron Beam Irradiation on the Photocatalytic Organic Dye Decomposition Efficiency of Graphitic Carbon Nitride. C. 2025; 11(4):91. https://doi.org/10.3390/c11040091

Chicago/Turabian StyleHarako, Aika, Shuhei Shimoda, Keita Suzuki, Atsushi Fukuoka, and Tomoya Takada. 2025. "Combined Effect of Sonication and Electron Beam Irradiation on the Photocatalytic Organic Dye Decomposition Efficiency of Graphitic Carbon Nitride" C 11, no. 4: 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/c11040091

APA StyleHarako, A., Shimoda, S., Suzuki, K., Fukuoka, A., & Takada, T. (2025). Combined Effect of Sonication and Electron Beam Irradiation on the Photocatalytic Organic Dye Decomposition Efficiency of Graphitic Carbon Nitride. C, 11(4), 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/c11040091