Metal-Doped Carbon Dots as Heterogeneous Fenton Catalysts for the Decolourisation of Dyes—Activity Relationships and Mechanistic Insights

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Materials

2.2. Synthesis of Metal-Doped CDs

2.3. Characterisation Method for Samples

2.3.1. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

2.3.2. X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS)

2.3.3. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

2.3.4. Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometer (ICP-MS)

2.3.5. Fluorescence Analysis

2.3.6. Zeta Potential Determination

2.4. Catalytic Degradation of Methylene Blue and Rhodamine Blue

2.5. Kinetic Analysis

2.6. Statistical Analyses

3. Result and Discussion

3.1. Characterisation of Metal-Doped CDs and Their Catalytic Implications

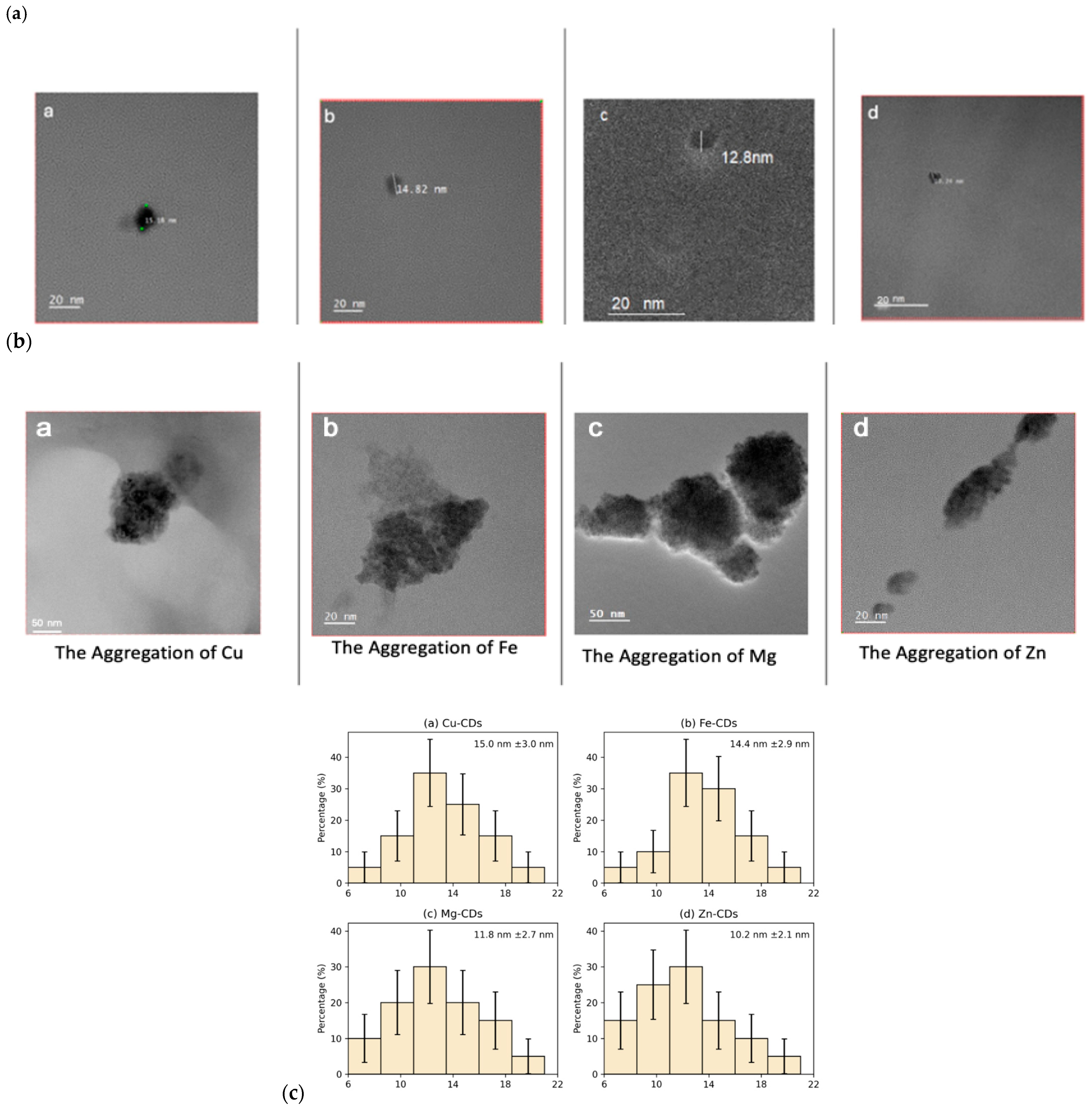

3.1.1. TEM Analysis

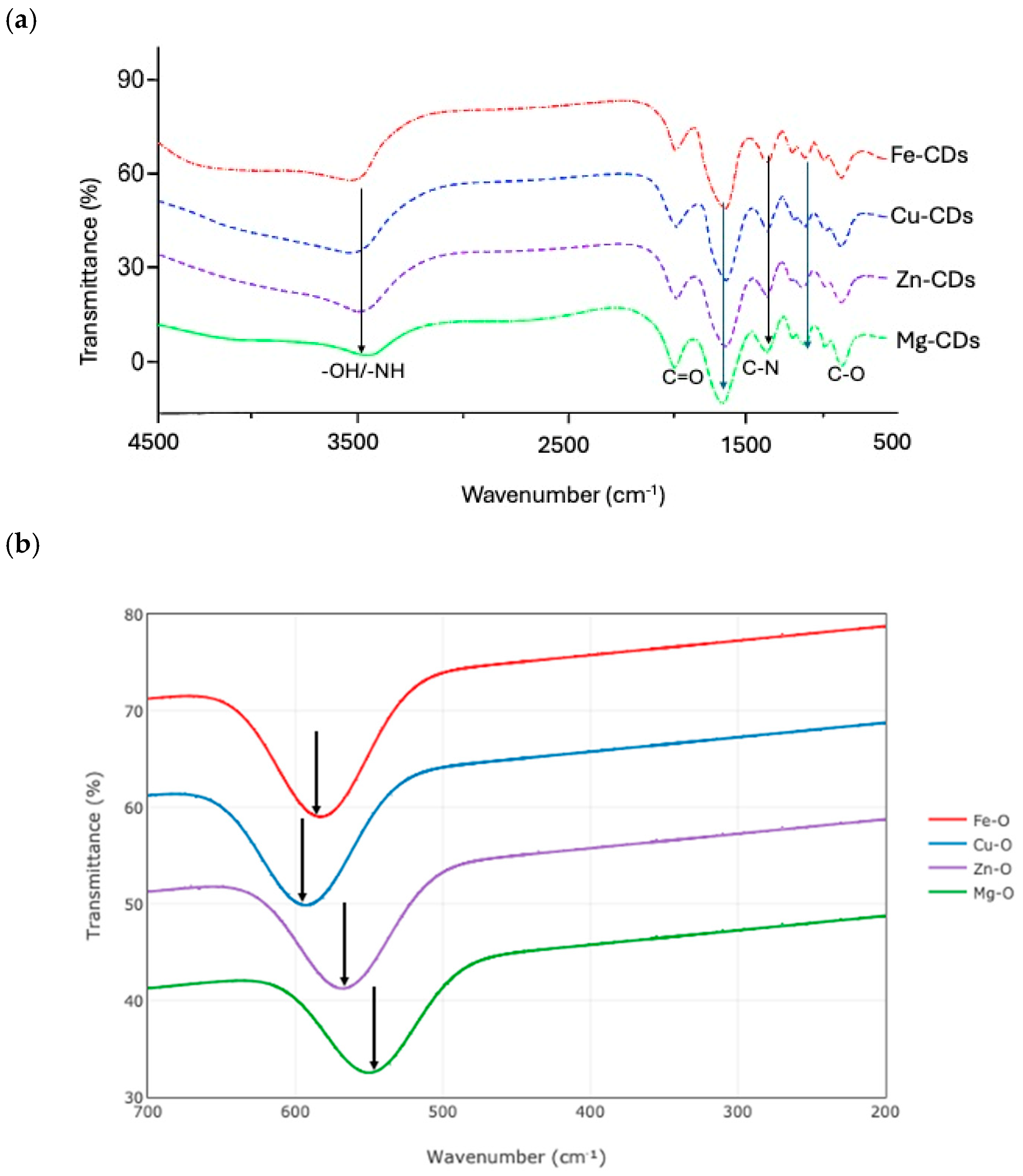

3.1.2. FTIR Analysis

3.1.3. ICP-MS Analysis

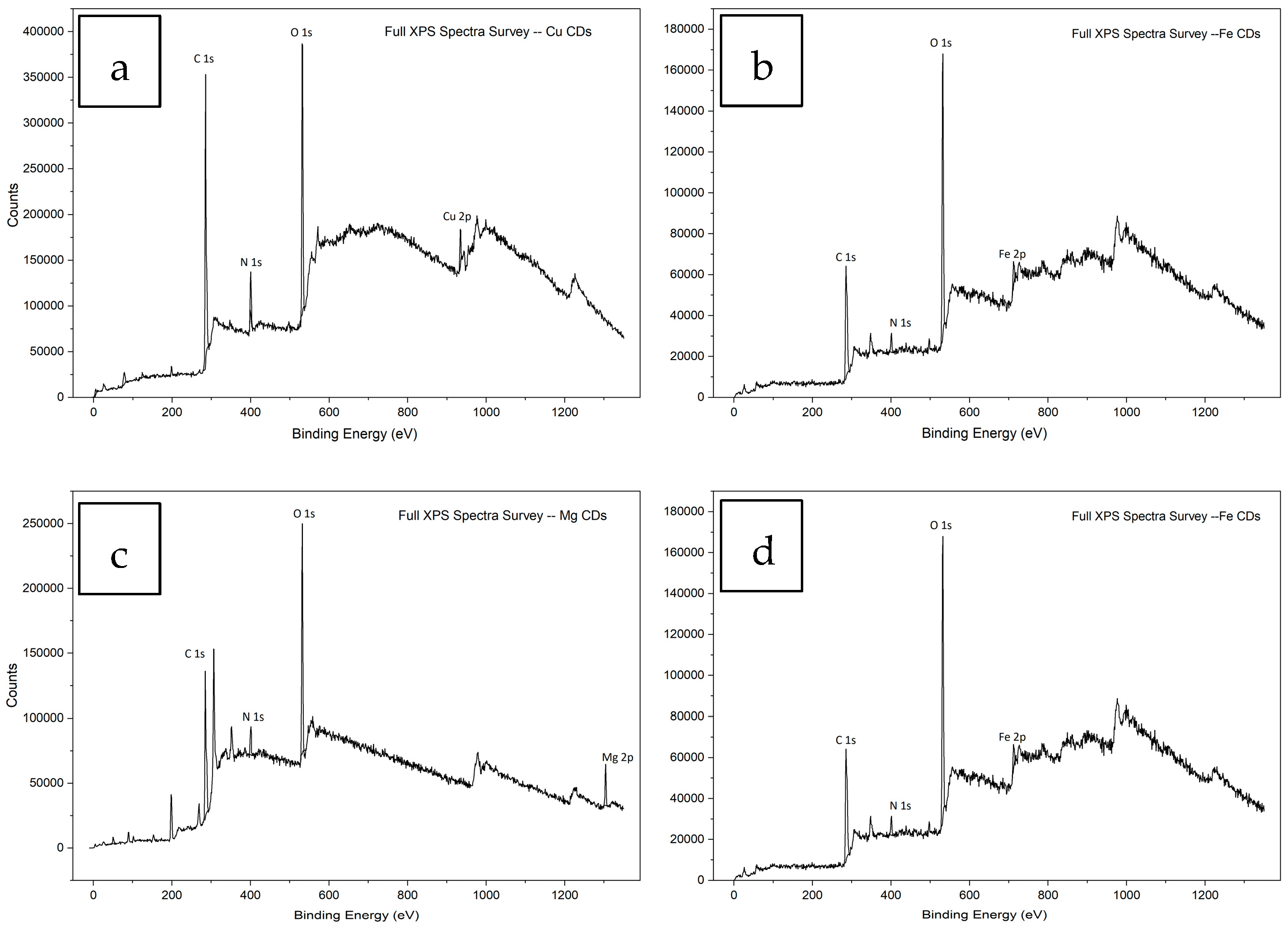

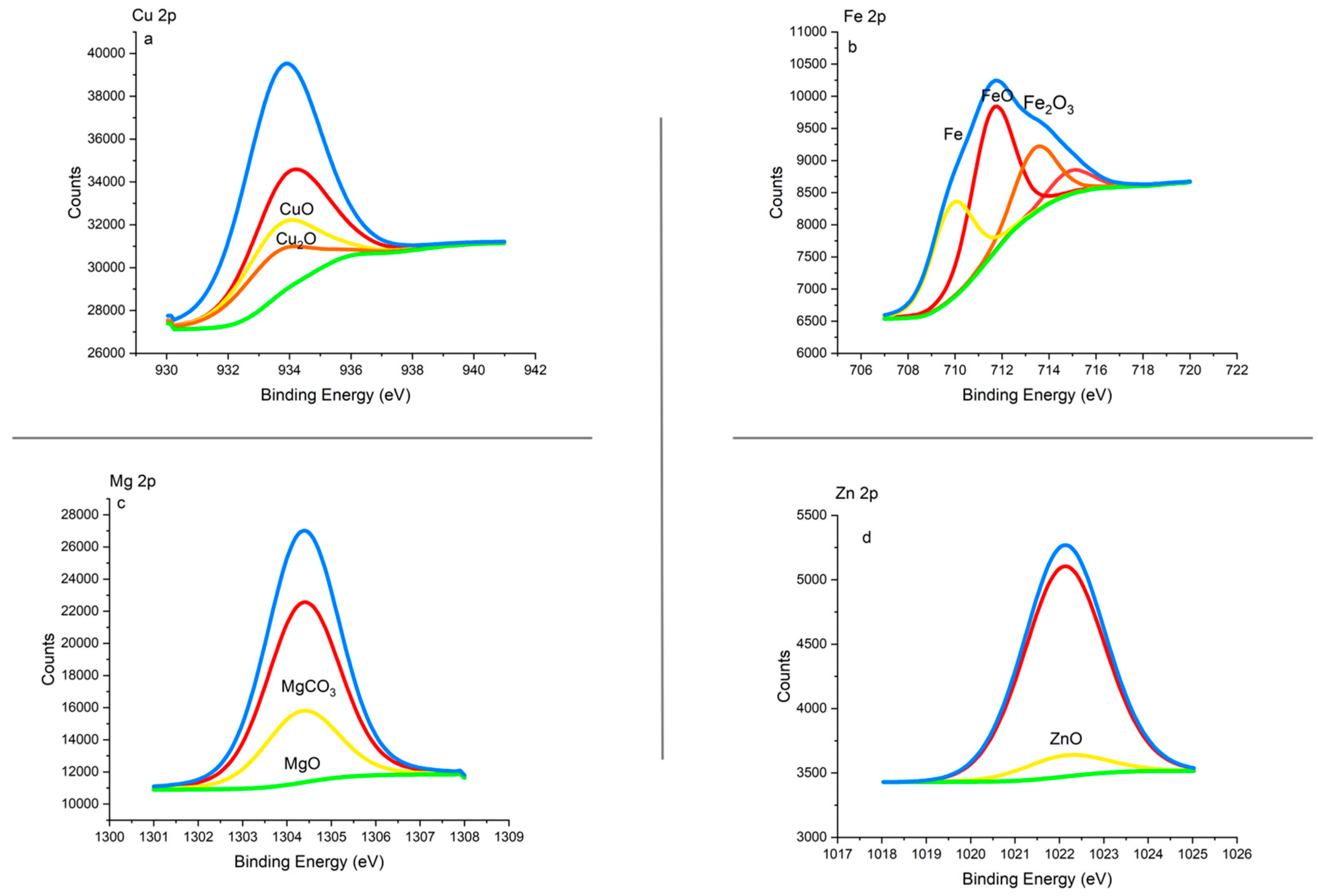

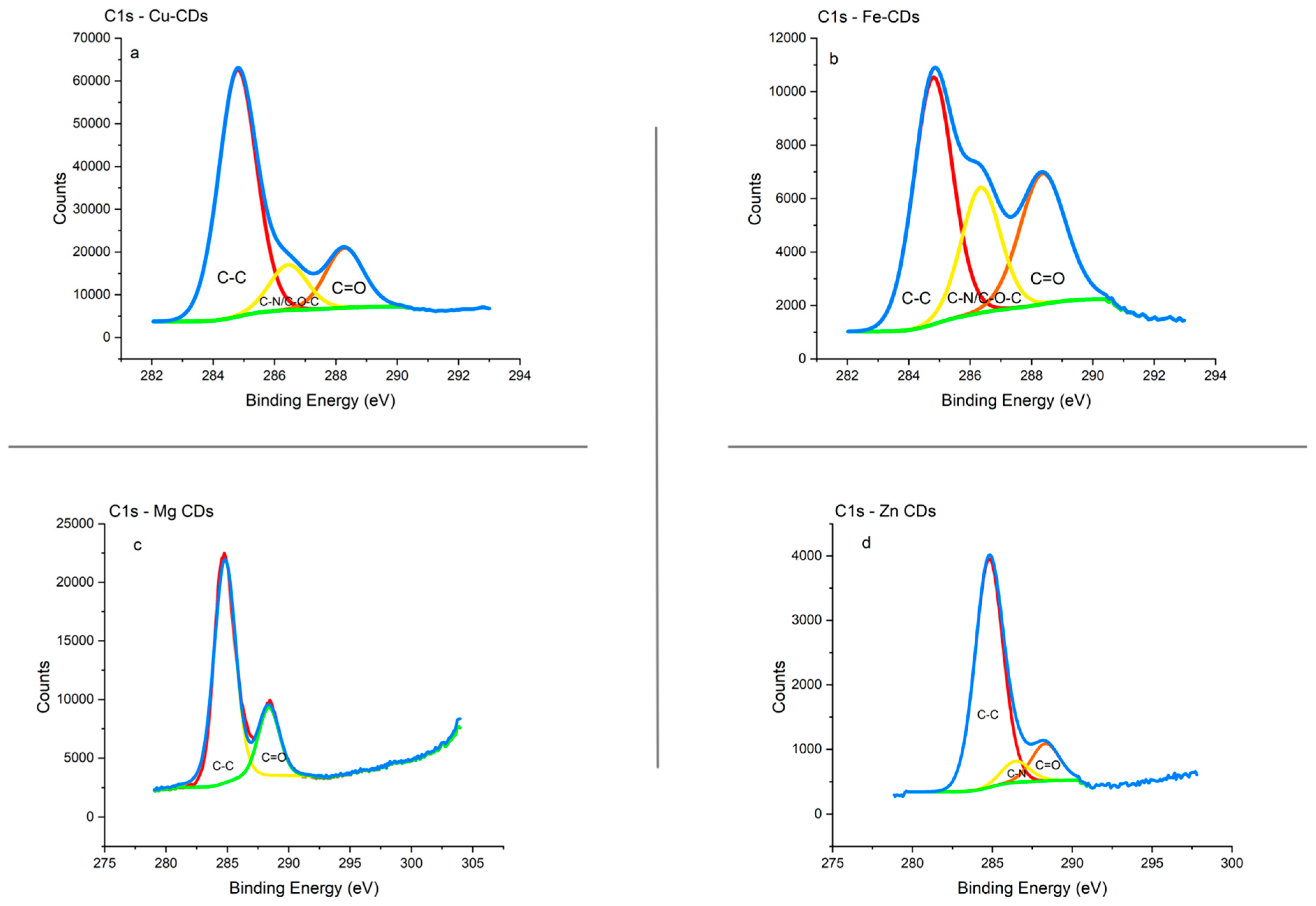

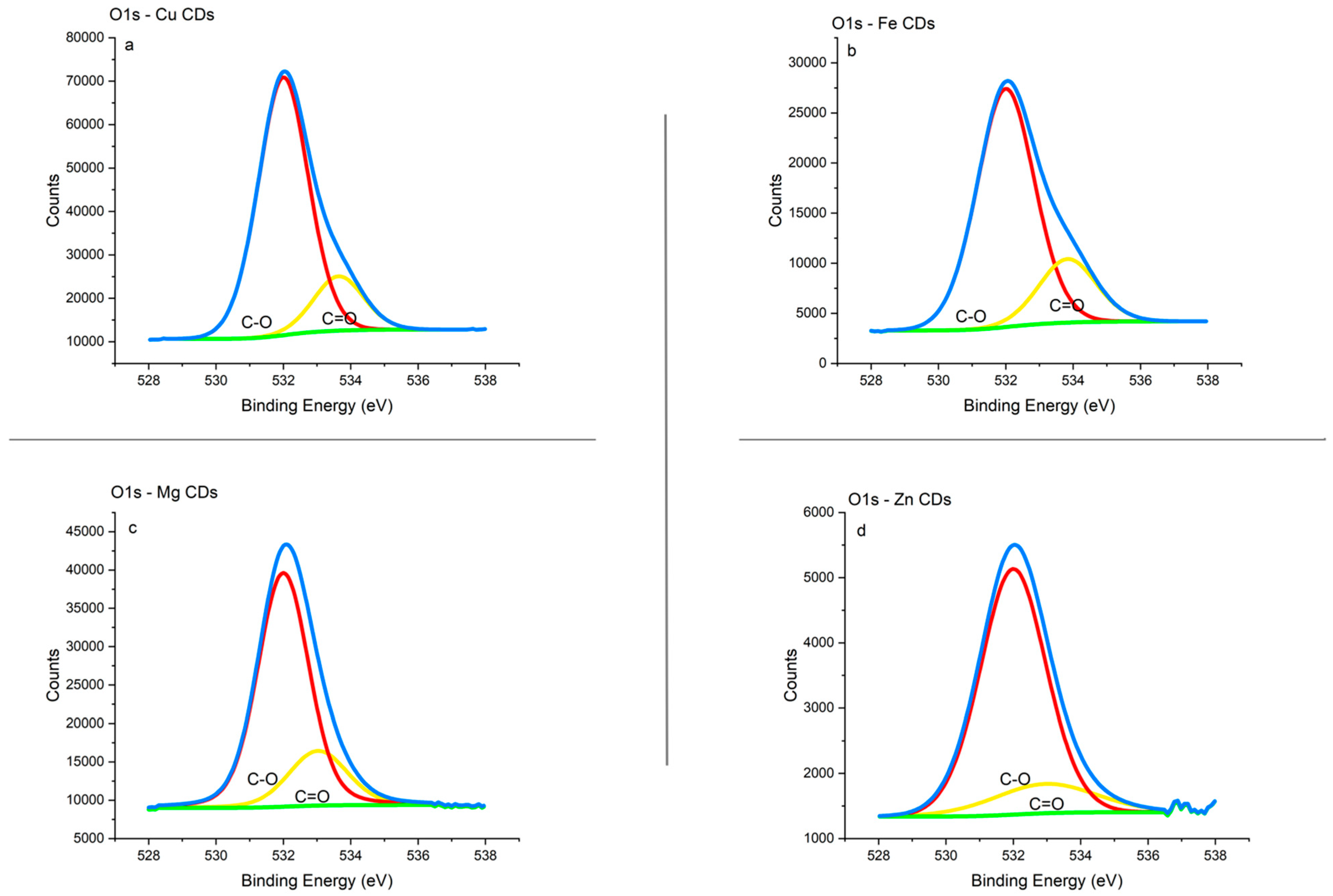

3.1.4. XPS Analysis

3.1.5. Integration of ICP-MS; FTIR and XPS

3.1.6. Zeta Potential Measurements

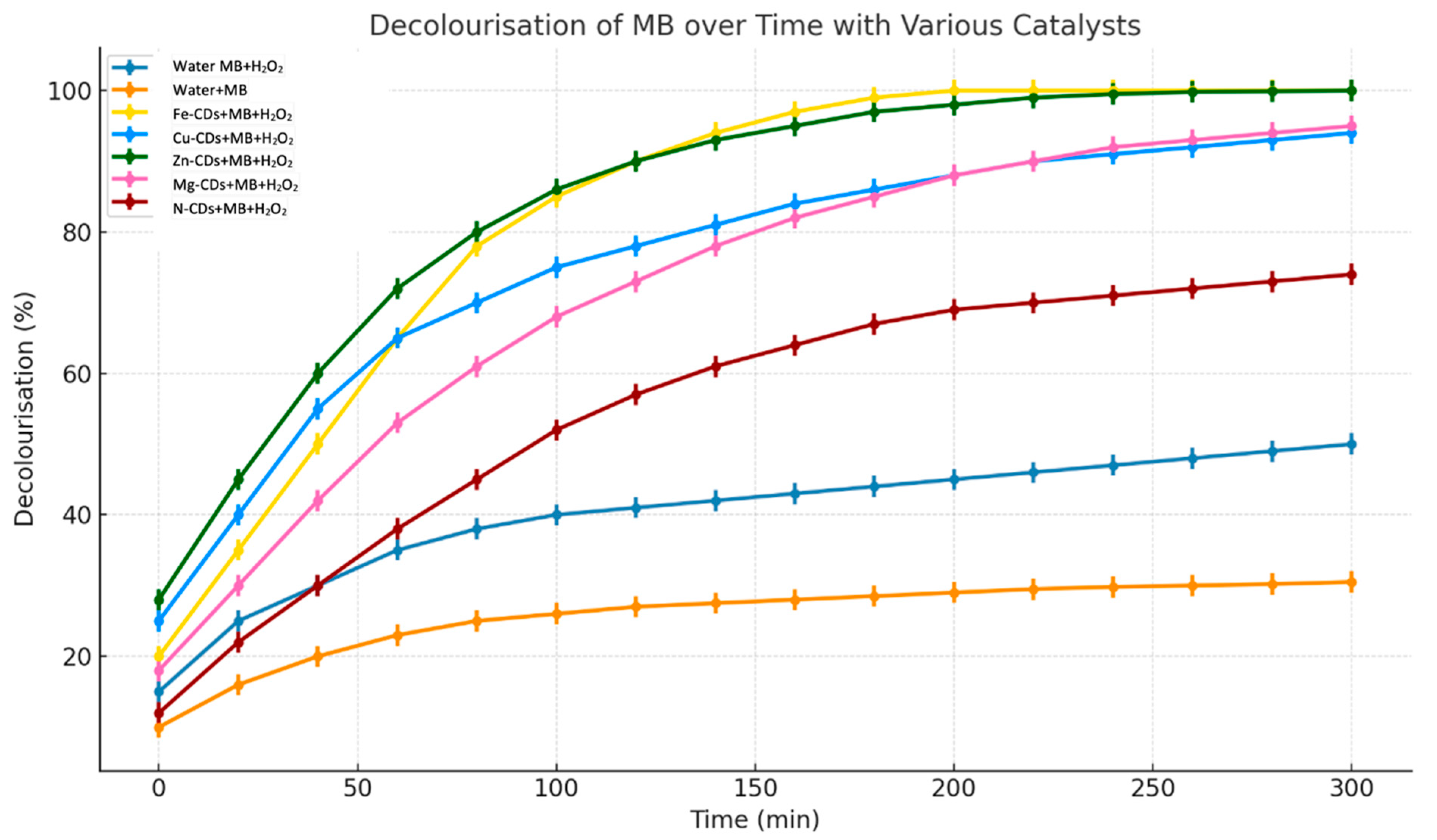

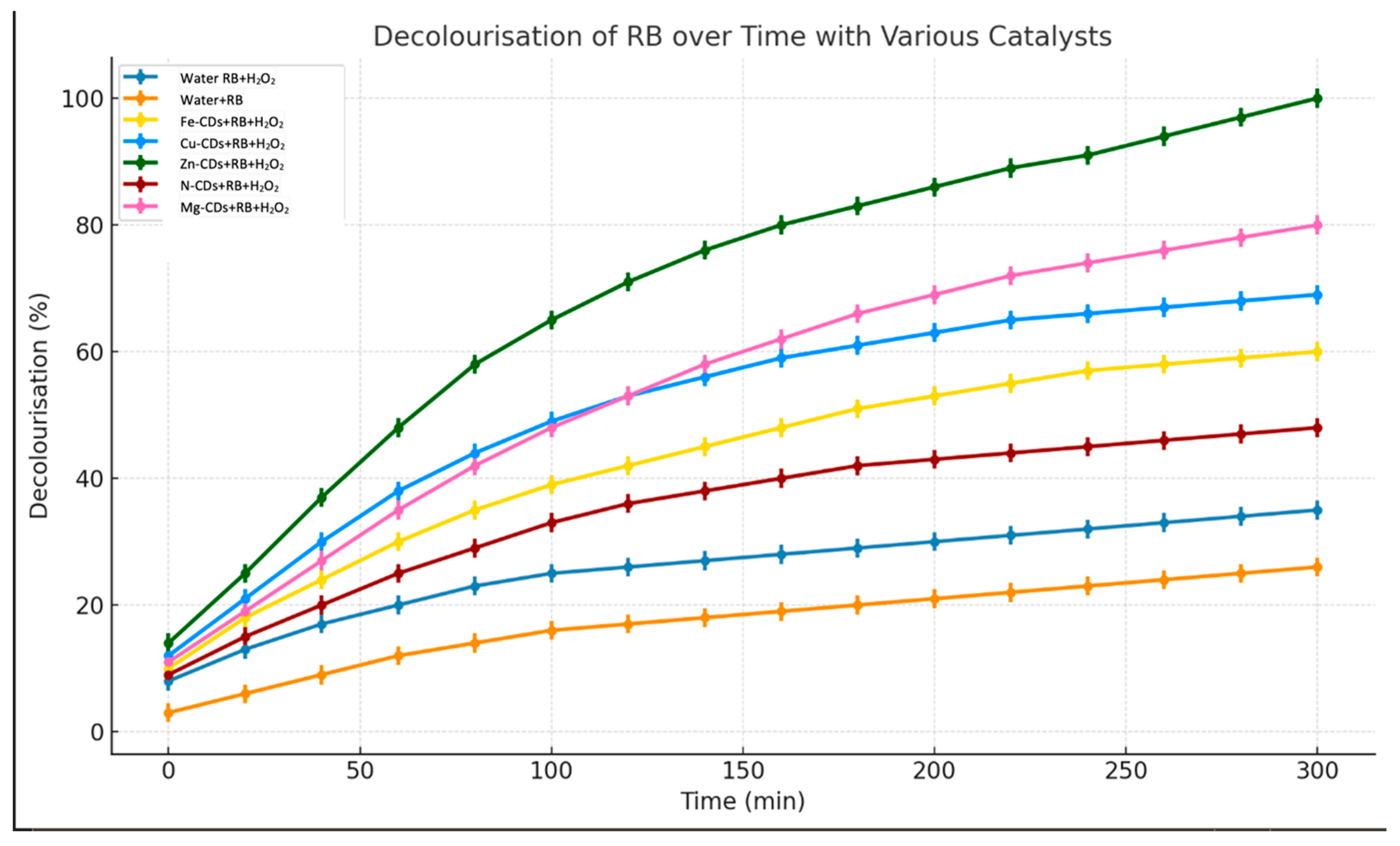

3.2. Catalytic Degradation Performance of Metal-Doped CDs

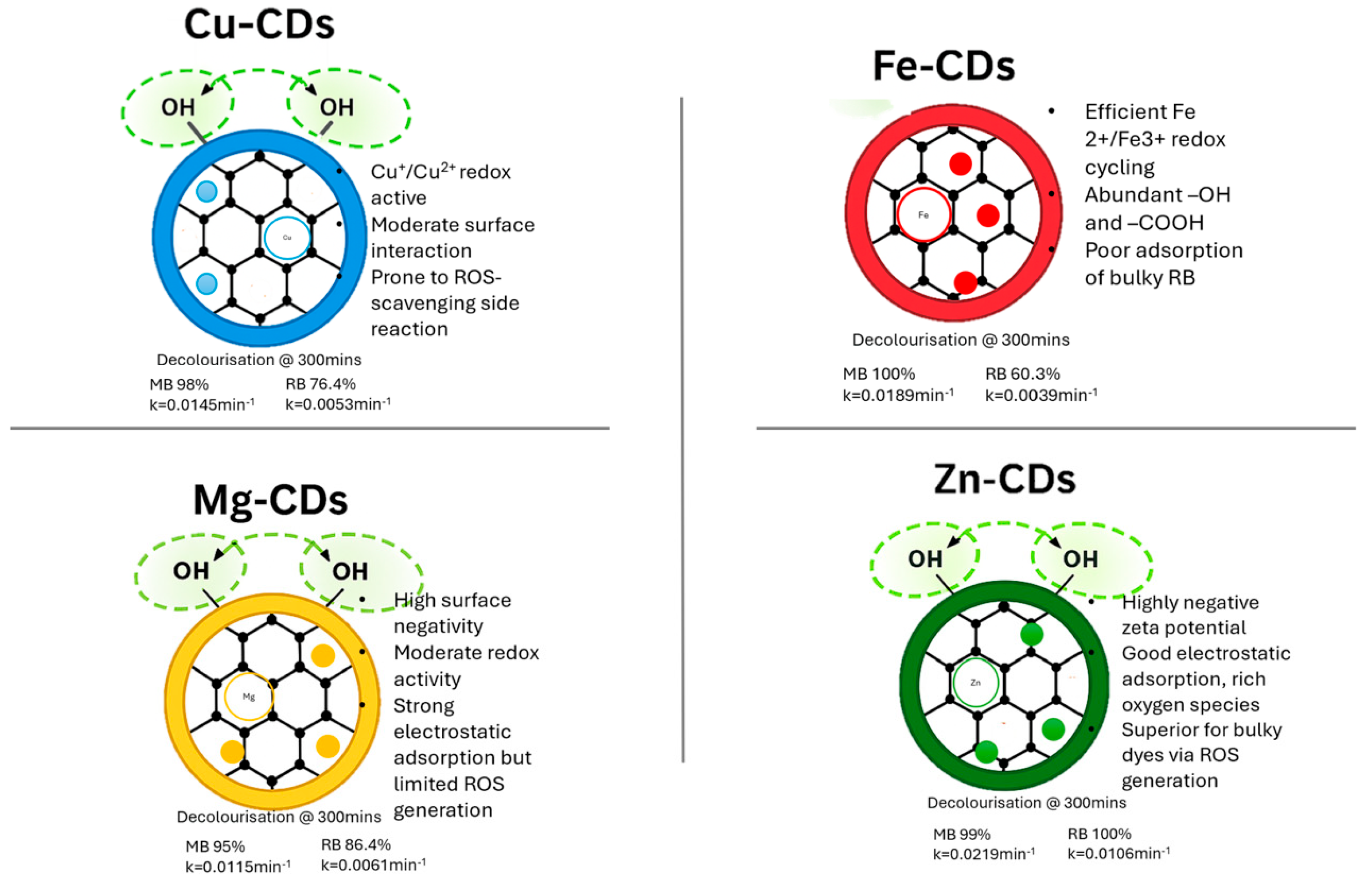

3.3. Structure-Function Correlation in Metal-Doped CDs for Dye Degradation

3.3.1. Catalytic Performance of Fe-Doped CDs

3.3.2. Catalytic Performance of Zn-Doped CDs

3.3.3. Catalytic Performance of Cu-Doped CDs

3.3.4. Catalytic Performance of Mg-Doped CDs

3.4. Future Investigations and Catalyst Stability

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al-Tohamy, R.; Ali, S.S.; Li, F.; Okasha, K.M.; Mahmoud, Y.A.-G.; Elsamahy, T.; Jiao, H.; Fu, Y.; Sun, J. A critical review on the treatment of dye-containing wastewater: Ecotoxicological and health concerns of textile dyes and possible remediation approaches for environmental safety. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 231, 113160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katheresan, V.; Kansedo, J.; Lau, S.Y. Efficiency of various recent wastewater dye removal methods: A Review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 4676–4697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagub, M.T.; Sen, T.K.; Afroze, S.; Ang, H.M. Dye and its removal from aqueous solution by adsorption: A Review. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2014, 209, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saratale, R.; Saratale, G.; Chang, J.; Govindwar, S. Bacterial decolorization and degradation of azo dyes: A Review. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2011, 42, 138–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lellis, B.; Fávaro-Polonio, C.Z.; Pamphile, J.A.; Polonio, J.C. Effects of textile dyes on health and the environment and bioremediation potential of living organisms. Biotechnol. Res. Innov. 2019, 3, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forgacs, E.; Cserháti, T.; Oros, G. Removal of synthetic dyes from Wastewaters: A Review. Environ. Int. 2004, 30, 953–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Ye, W.; Xie, M.; Seo, D.H.; Luo, J.; Wan, Y.; Van der Bruggen, B. Environmental impacts and remediation of dye-containing wastewater. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 785–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, S. Reactive species in advanced oxidation processes: Formation, identification and reaction mechanism. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 401, 126158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, L.; Ji, H. Preparation of 2D/2D coal-LDH/bio(oh)xi1−x heterojunction catalyst with enhanced visible–light photocatalytic activity for organic pollutants degradation in water. Water 2024, 16, 1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K. Fenton Reaction: A Brief Overview, SPERTA MEMBRANE. 2024. Available online: https://spertasystems.com/fenton-reaction-overview (accessed on 17 August 2025).

- Akram, Z.; Raza, A.; Mehdi, M.; Arshad, A.; Deng, X.; Sun, S. Recent advancements in metal and non-metal mixed-doped carbon quantum dots: Synthesis and emerging potential applications. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, H.; Xin, Q.; Jia, X.; Gong, J.R. Single precursor-based luminescent nitrogen-doped carbon dots and their application for iron (III) sensing. Arab. J. Chem. 2019, 12, 1083–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallareta-Olivares, G.; Rivas-Sanchez, A.; Cruz-Cruz, A.; Hussain, S.M.; González-González, R.B.; Cárdenas-Alcaide, M.F.; Iqbal, H.M.; Parra-Saldívar, R. Metal-doped carbon dots as robust nanomaterials for the monitoring and degradation of water pollutants. Chemosphere 2023, 312, 137190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu-Melha, S. Metal-doped carbon quantum dots for catalytic discoloration of methylene blue in day light. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2024, 447, 115233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Fan, X.; Guan, R.; Hu, Y.; Jiang, S.; Shao, X.; Wang, S.; Yue, Q. Carbon dots as metal-free photocatalyst for dye degradation with high efficiency within nine minutes in dark. Opt. Mater. 2022, 123, 111914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, A.; Varghese, A.; Kalathiparambil Rajendra, S.D.; Pinheiro, D. Comprehensive understanding of biomedical usages of metal and non metal doped carbon dots. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 37, 106991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hübner, C.; Haase, H. Interactions of zinc- and redox-signaling pathways. Redox Biol. 2021, 41, 101916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Tang, Y.; Xiong, D.; Zhang, W.; Liu, Z.; Chu, P.K.; Wang, G. Carbon dots for reactive oxygen species modulation. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2025, 166, 101024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIST Office of Data and Informatics. Rhodamine B. 2025. Available online: https://webbook.nist.gov/cgi/cbook.cgi?ID=C81889&Mask=FFF&utm_source (accessed on 17 August 2025).

- NIST Office of Data and Informatics. Methylene Blue. 2025. Available online: https://webbook.nist.gov/cgi/inchi?ID=C61734&Mask=80&utm_source (accessed on 17 August 2025).

- Evdokimenko, N.; Vikanova, K.; Bazlov, A.; Tkachenko, O.; Kapustin, G.; Kalmykov, K.; Tedeeva, M.; Beresnev, K.; Kustov, L.; Kustov, A. Effect of the nature of iron precursors on the activity of Fe-containing catalysts in CO2 conversion. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2024, 688, 119998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S. Influence of synthesis strategy on the formation of microspheres of self-assembled CuO rectangular nanorods and hierarchical structures of self-assembled Cu2O nanospheres from single precursor (copper (II) acetate monohydrate) and their structural, optical, thermal and magnetic properties. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2021, 258, 123929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasnidawani, J.; Azlina, H.; Norita, H.; Bonnia, N.; Ratim, S.; Ali, E. Synthesis of ZnO Nanostructures Using Sol-Gel Method. Procedia Chem. 2016, 19, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasiri, P.; Saviz, S.; Dorranian, D.; Sari, A.H. MgO/MgAl2O4 nanocomposites synthesis by plasma torch from aqueous solution of MgCl2 and AlCl3 salts and studying the effect of raw material concentration on the products. Appl. Phys. A 2022, 128, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikmen, S. Hydrothermal synthesis and properties of Ce1−xBixO2−δ solid solutions. Solid State Ionics 1998, 112, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, W.; Lee, A.; Tae, Y.; Lee, B.; Choi, J.-S. Enhancing catalytic efficiency of carbon dots by modulating their Mn doping and chemical structure with metal salts. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 8996–9002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, P.; Ghobadifard, M.; Mohebbi, S.; Ashengroph, M. The performance of Metal Carbon-based quantum dots as an anti-bacterial factor in green conditions. J. Organomet. Chem. 2024, 1026, 123495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeing, G.; Rendón-Angeles, J.C. Hydrothermal Synthesis of Nanoparticles; Preprint; MDPI Books: Basel, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraldi, M.; Ferrari, R.; Auriemma, R.; Sponchioni, M.; Moscatelli, D. Concentration of polymer nanoparticles through dialysis: Efficacy and comparison with lyophilization for pegylated and zwitterionic systems. J. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 109, 2607–2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beker, S.A.; Khudur, L.S.; Cole, I.; Ball, A.S. Catalytic degradation of methylene blue using iron and nitrogen-containing carbon dots as Fenton-like catalysts. New J. Chem. 2021, 46, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Luo, Y.; Tsai, P.; Wang, J.; Chen, X. Metal ions doped carbon quantum dots: Synthesis, physicochemical properties, and their applications. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2018, 103, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Fu, Y.; Zhao, S.; Xiao, J.; Lan, M.; Wang, B.; Zhang, K.; Song, X.; Zeng, L. Metal ions-doped carbon dots: Synthesis, properties, and applications. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 430, 133101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anpalagan, K.; Yin, H.; Cole, I.; Zhang, T.; Lai, D.T.H. Quantum yield enhancement of carbon quantum dots using chemical-free precursors for sensing Cr (VI) ions. Inorganics 2024, 12, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Xi, R.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, P.; Hu, D. Recent development of transition metal doped carbon materials derived from biomass for hydrogen evolution reaction. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 32436–32454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tantra, R.; Schulze, P.; Quincey, P. Effect of nanoparticle concentration on zeta-potential measurement results and reproducibility. Particuology 2010, 8, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Kang, D.; Jeong, S.; Do, H.T.; Kim, J.H. Photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B dye by TiO2 and gold nanoparticles supported on a floating porous polydimethylsiloxane sponge under ultraviolet and visible light irradiation. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 4233–4241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salari, H. Kinetics and mechanism of enhanced photocatalytic activity under visible light irradiation using Cr2O3/Fe2O3 nanostructure derived from bimetallic metal organic framework. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 103092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravanan, R.; Shankar, H.; Rajasudha, G.; Stephen, A.; Narayanan, V. Photocatalytic degradation of organic dye using nano ZnO. Int. J. Nanosci. 2011, 10, 253–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Jin, C.; Li, Y.; Shen, W. Dynamic behavior of metal nanoparticles for catalysis. Nano Today 2018, 20, 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jozanikohan, G.; Abarghooei, M.N. The Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) analysis for the Clay Mineralogy Studies in a clastic reservoir. J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 2022, 12, 2093–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosvenor, A.P.; Kobe, B.A.; Biesinger, M.C.; McIntyre, N.S. Investigation of multiplet splitting of Fe 2P XPS spectra and bonding in Iron Compounds. Surf. Interface Anal. 2004, 36, 1564–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran, P.; Arul, V.; Sethuraman, M.G. Ecofriendly synthesis of fluorescent nitrogen-doped carbon dots from Coccinia grandis and its efficient catalytic application in the reduction of methyl orange. J. Fluoresc. 2019, 30, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, T.; Maslakov, K.; Sidorov, A.; Kiskin, M.; Linko, R.; Savilov, S.; Lunin, V.; Eremenko, I. XPS detection of unusual Cu(ii) to Cu(I) transition on the surface of complexes with redox-active ligands. J. Electron Spectrosc. Relat. Phenom. 2020, 238, 146878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhai, Y.; Li, L. Study on the properties of the MGCO3@2MN1−XMXCO3 carbonate composite material as a cathode electrode in the aqueous zinc-ion battery and the effect of Ag Ion doping at the Manganese Site. AIP Adv. 2023, 13, 085113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Cai, W.; Zhang, M.; Su, R.; Ye, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Guo, Y.; Yu, Z.; Li, S.; et al. Photoluminescence mechanism and applications of Zn-Doped Carbon Dots. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 17254–17262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Liao, W. Hierarchical carbon material of N-doped carbon quantum dots in-situ formed on N-doped carbon nanotube for efficient oxygen reduction. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 495, 143597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, F.P.; Rastogi, A.; Singh, S. Optical properties and zeta potential of carbon quantum dots (CQDs) dispersed nematic liquid crystal 4′- heptyl-4-biphenylcarbonitrile (7CB). Opt. Mater. 2020, 105, 109849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohail, M.; Xie, B.; Li, B.; Huang, H. Zn-doped carbon dots-based versatile bioanalytical probe for precise estimation of antioxidant activity index of multiple samples via Fenton chemistry. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2022, 363, 131558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xie, T.; Liu, X.; Wu, D.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Fan, X.; Zhang, F.; Peng, W. Enhanced redox cycle of Fe3+/Fe2+ on Fe@NC by boron: Fast electron transfer and long-term stability for Fenton-like reaction. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 445, 130605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wirecka, R.; Lachowicz, D.; Berent, K.; Marzec, M.; Bernasik, A. Ion distribution in iron oxide, zinc and manganese ferrite nanoparticles studied by XPS combined with argon gas cluster ion beam sputtering. Surf. Interfaces 2022, 30, 101865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.J.; Chakraborty, A.; Sehgal, R. A systematic review of industrial wastewater management: Evaluating challenges and enablers. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 348, 119230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beker, S.A.; Khudur, L.S.; Krohn, C.; Cole, I.; Ball, A.S. Remediation of groundwater contaminated with dye using carbon dots technology: Ecotoxicological and Microbial Community responses. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 319, 115634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brillas, E.; Martínez-Huitle, C.A. Decontamination of wastewaters containing synthetic organic dyes by electrochemical methods. An updated review. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2015, 166–167, 603–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, S.; Liang, K.; Zhu, J.; Yang, B.; Zhao, D.; Kong, B. Hetero-atom-doped carbon dots: Doping strategies, properties and applications. Nano Today 2020, 33, 100879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Vione, D.; Rivoira, L.; Carena, L.; Castiglioni, M.; Bruzzoniti, M.C. A review on the degradation of pollutants by Fenton-like systems based on zero-valent iron and persulfate: Effects of reduction potentials, PH, and anions occurring in waste waters. Molecules 2021, 26, 4584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, K. Biogenic synthesis of Allium cepa derived magnetic carbon dots for enhanced photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue and rhodamine B dyes. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2023, 15, 869–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basavaraj, N.; Sekar, A.; Yadav, R. Review on green carbon dot-based materials for the photocatalytic degradation of dyes: Fundamentals and Future Perspective. Mater. Adv. 2021, 2, 7559–7582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazzaf, H.; Nechchadi, B.; Jouali, A.; Salhi, A.; El Krati, M.; Tahiri, S. Synthesis of heterogeneous photo-fenton catalyst from Iron Rust and its application to degradation of acid red 97 in aqueous medium. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 107570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Fan, Z. Application of magnesium ion doped carbon dots obtained via hydrothermal synthesis for arginine detection. New J. Chem. 2020, 44, 4842–4849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artyushkova, K.; Fulghum, J.E. Identification of chemical components in XPS spectra and images using multivariate statistical analysis methods. J. Electron Spectrosc. Relat. Phenom. 2001, 121, 33–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Wang, B.; Wang, T.; Li, C.; Wang, W.; Wang, M.; Zhang, J. One-pot synthesis of Zn–CdS@C nanoarchitecture with improved photocatalytic performance toward antibiotic degradation. Chemosphere 2022, 300, 134621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, L.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Z.; Zhu, J.; Zhamaerding, A.; Feng, L.; Yang, D.; Meng, L.; He, C.; Wang, W.; et al. Multi-dimensional micro-nano scale manganese oxide catalysts induced chemical-based advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) in environmental applications: A critical review. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 474, 145600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, O.S.G.P.; Rodrigues, C.S.D.; Madeira, L.M.; Pereira, M.F.R. Heterogeneous fenton-like degradation of P-nitrophenol over tailored carbon-based materials. Catalysts 2019, 9, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Shan, P.; Xu, R.; Sun, X.; Hou, J.; Guo, F.; Li, C.; Shi, W. Boosted photo-self-Fenton degradation activity by Fe-doped carbon dots as dual-function active sites for in-situ H2O2 generation and activation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 353, 128529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, A.; Hagos, M.; Belachew, N.; Murthy, H.C.A.; Basavaiah, K. Enhanced photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B, antibacterial and antioxidant activities of green synthesised ZnO/N doped carbon quantum dot nanocomposites. New J. Chem. 2021, 45, 21852–21862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tammina, S.K.; Yang, D.; Li, X.; Koppala, S.; Yang, Y. High photoluminescent nitrogen and zinc doped carbon dots for sensing Fe3+ ions and temperature. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2019, 222, 117141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, M.; Shanker, U. Sun-light driven rapid photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue by poly(methyl methacrylate)/metal oxide nanocomposites. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2018, 559, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borzyszkowska, A.F.; Sulowska, A.; Czaja, P.; Bielicka-Giełdoń, A.; Zekker, I.; Zielińska-Jurek, A. ZnO-decorated green-synthesized multi-doped carbon dots from Chlorella pyrenoidosa for sustainable photocatalytic carbamazepine degradation. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 25529–25551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alomar, M.; Liu, Y.; Chen, W. Surface decorated Zn0.15Cd0.85S nanoflowers with P25 for enhanced visible light driven photocatalytic degradation of Rh-B and stability. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, P.; Ganguly, S.; Bose, M.; Mondal, S.; Choudhary, S.; Gangopadhyay, S.; Das, A.K.; Banerjee, S.; Das, N.C. Zinc and nitrogen ornamented bluish white luminescent carbon dots for engrossing bacteriostatic activity and Fenton based bio-sensor. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2018, 88, 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Kuo, D.-H.; Saragih, A.D.; Wu, Z.-Y.; Abdullah, H.; Lin, J. The effect of the Cu+/Cu2+ ratio on the redox reactions by nanoflower CuNiOS catalysts. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2019, 194, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamenković, T.; Bundaleski, N.; Barudžija, T.; Validžić, I.; Lojpur, V. XPS study of iodine and tin doped Sb2S3 nanostructures affected by non-uniform charging. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 567, 150822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Ball, A.S.; Cole, I.; Yin, H. Metal-doped carbon dots as Fenton-like catalysts and their applications in pollutant degradation and sensing. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, P.; Kumar, A. Advanced oxidation process: A remediation technique for organic and non-biodegradable pollutant. Results Surf. Interfaces 2023, 11, 100122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Meng, Q.; Wang, L.; Zhang, J.; Song, Y.; Jin, H.; Zhang, K.; Sun, H.; Wang, H.; Yang, B. Highly photoluminescent carbon dots for multicolor patterning, sensors, and bioimaging. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 3953–3957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Wavenumber (cm−1) | Assigned Functional Group | Bond Type/Vibration Mode | Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| ~3290 | –OH/–NH | O–H and N–H stretching | Presence of surface hydroxyl and amine groups, enhancing substrate adsorption |

| ~1635 | C=O | Carbonyl/carboxyl stretching | Presence of –COOH or ketones, facilitating interaction with H2O2 |

| ~1265 | C–N | C–N stretching | Nitrogen doping and increased surface polarity |

| 1085 | C–O | C–O stretching | Carbon doping increased surface function |

| 582 | Fe–O | Metal–oxygen stretching | Fe doping relevant to Fenton-like redox cycling |

| 592 | Cu–O | Metal–oxygen stretching | Cu doping linked to electron transfer enhancement |

| 567 | Zn–O | Metal–oxygen stretching | Zn doping associated with high surface area and ROS pathways |

| 549 | Mg–O | Metal–oxygen stretching | Mg doping, improving surface polarity and adsorption |

| Sample | Mass of Precursors-Metal Only (mg) | Metal-Only Concentration (mg) | Retention Efficiency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fe–CDs | 150 | 21.6 | 14.4 |

| Cu–CDs | 318 | 158 | 49.7 |

| Zn–CDs | 298 | 62.9 | 21.1 |

| Mg–CDs | 248 | 143 | 57.7 |

| Catalyst Type | Dye | pH | Temp (°C) | Degradation Efficiency | k (min−1) | Cost & Scalability | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe-doped CDs | MB | 6.8 | 50 | 100% in 180 min | 0.0189 | Low-cost, scalable | This work– |

| Zn-doped CDs | RB | 6.8 | 50 | 100% in 300 min | 0.0106 | Low-cost, scalable | This work– |

| Fe3O4@SiO2–NH2 | MB | 3.0 | 25 | 96% in 120 min | 0.0082 | Moderate | [50] |

| MIL-88B (Fe-MOF) | MB | 5.5 | 45 | 92% in 180 min | 0.0121 | High-cost, less scalable | [58] |

| ZnO–biochar composite | RB | 7.0 | 30 | 85% in 240 min | 0.0042 | Low-cost | [18] |

| CuO nanoparticles | MB | 6.0 | 40 | 94% in 120 min | 0.0075 | Moderate | [59] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, W.; Cole, I.; Ball, A.S.; Yin, H. Metal-Doped Carbon Dots as Heterogeneous Fenton Catalysts for the Decolourisation of Dyes—Activity Relationships and Mechanistic Insights. C 2025, 11, 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/c11040087

Chen W, Cole I, Ball AS, Yin H. Metal-Doped Carbon Dots as Heterogeneous Fenton Catalysts for the Decolourisation of Dyes—Activity Relationships and Mechanistic Insights. C. 2025; 11(4):87. https://doi.org/10.3390/c11040087

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Weiyun, Ivan Cole, Andrew S. Ball, and Hong Yin. 2025. "Metal-Doped Carbon Dots as Heterogeneous Fenton Catalysts for the Decolourisation of Dyes—Activity Relationships and Mechanistic Insights" C 11, no. 4: 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/c11040087

APA StyleChen, W., Cole, I., Ball, A. S., & Yin, H. (2025). Metal-Doped Carbon Dots as Heterogeneous Fenton Catalysts for the Decolourisation of Dyes—Activity Relationships and Mechanistic Insights. C, 11(4), 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/c11040087