Bound Coherent Structures Propagating on the Free Surface of Deep Water

Abstract

1. Introduction

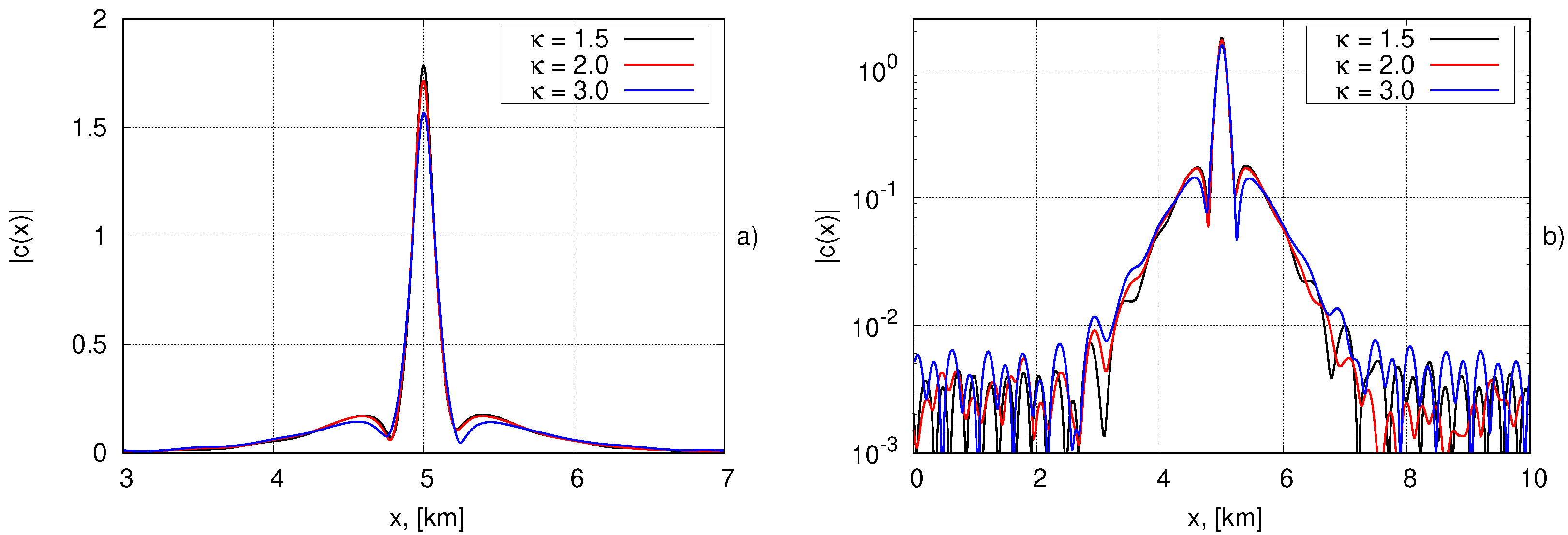

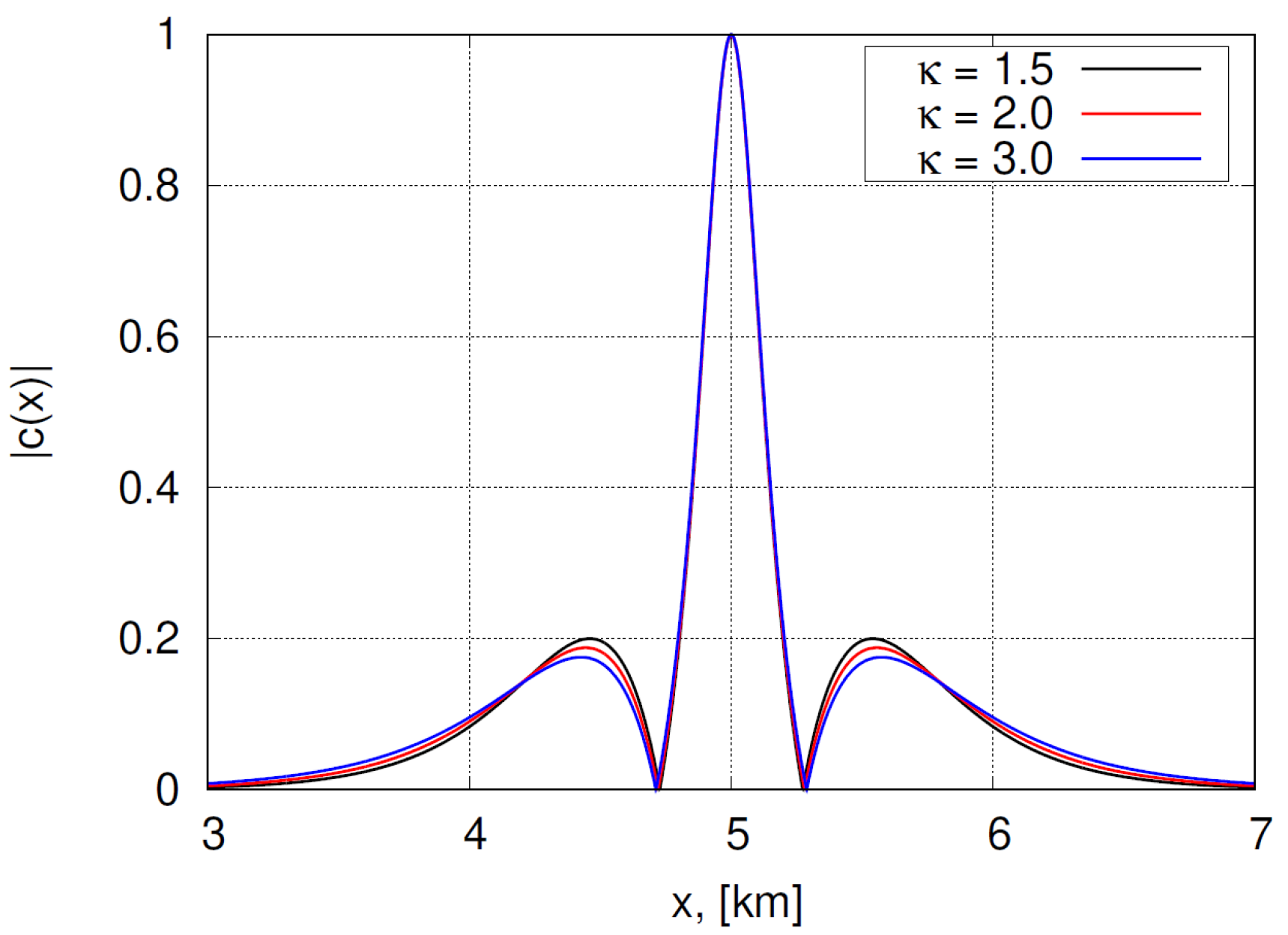

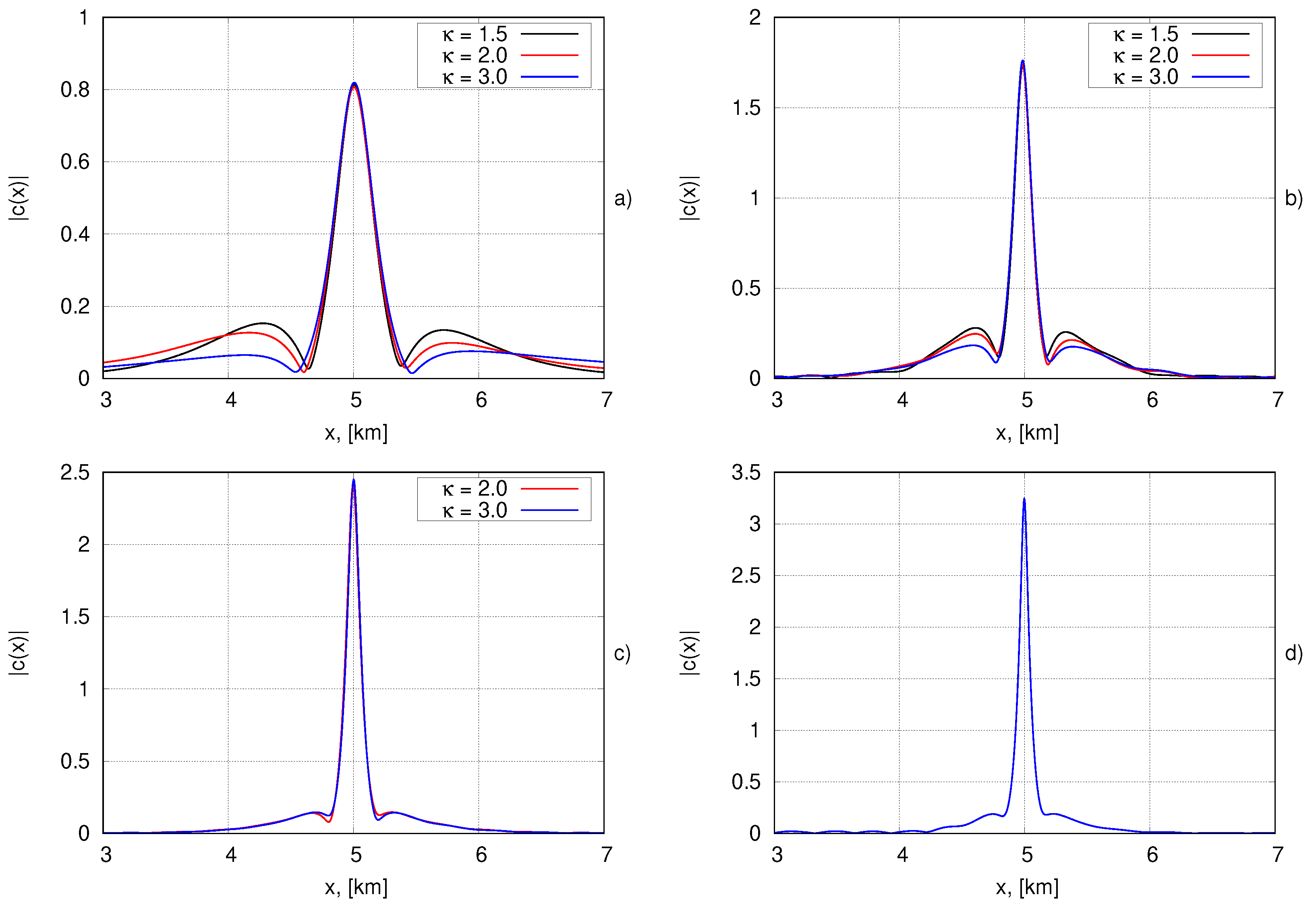

2. Deep Water Wave Equations

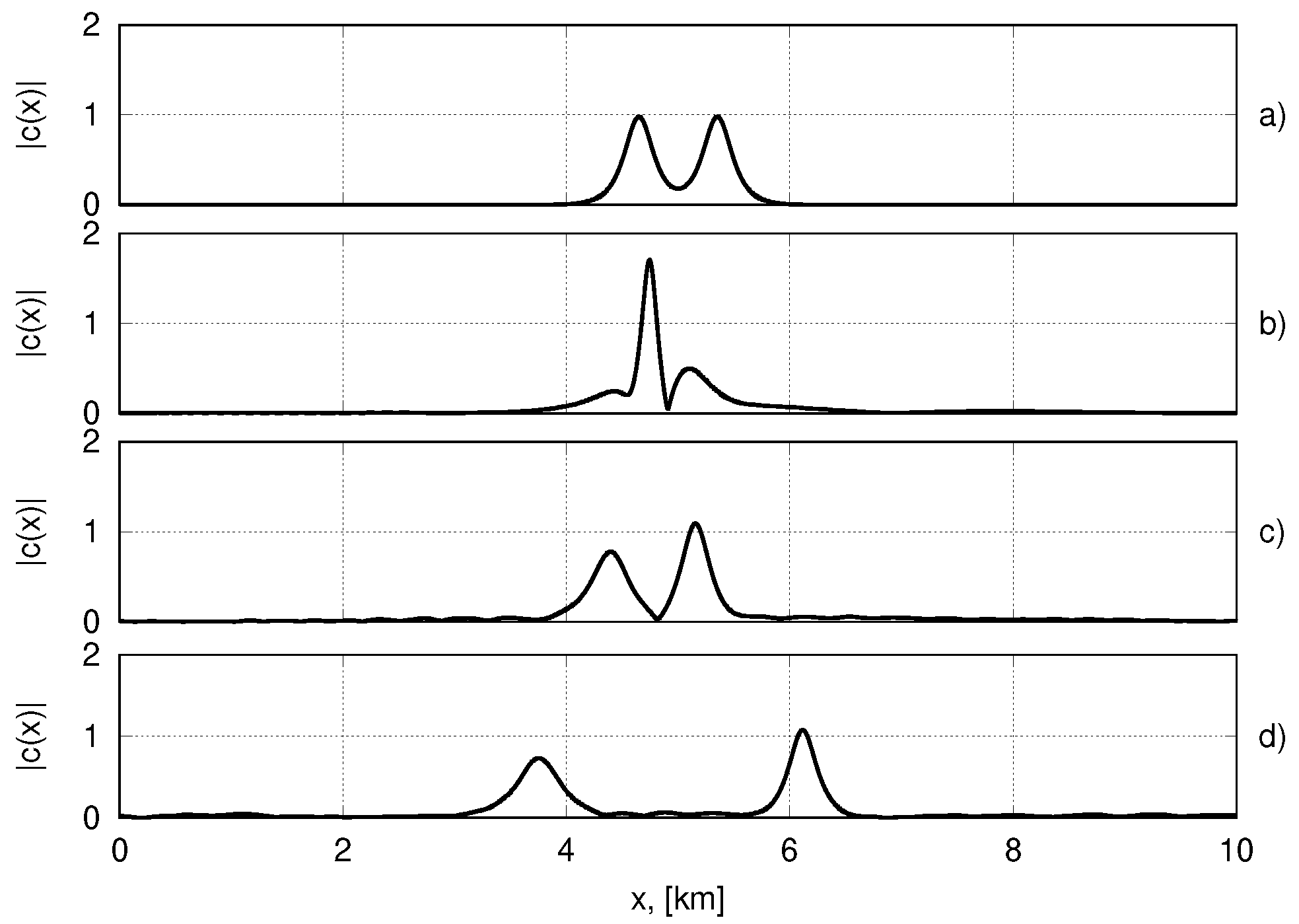

3. Bound Structures in the Super Compact Dyachenko-Zakharov Equation

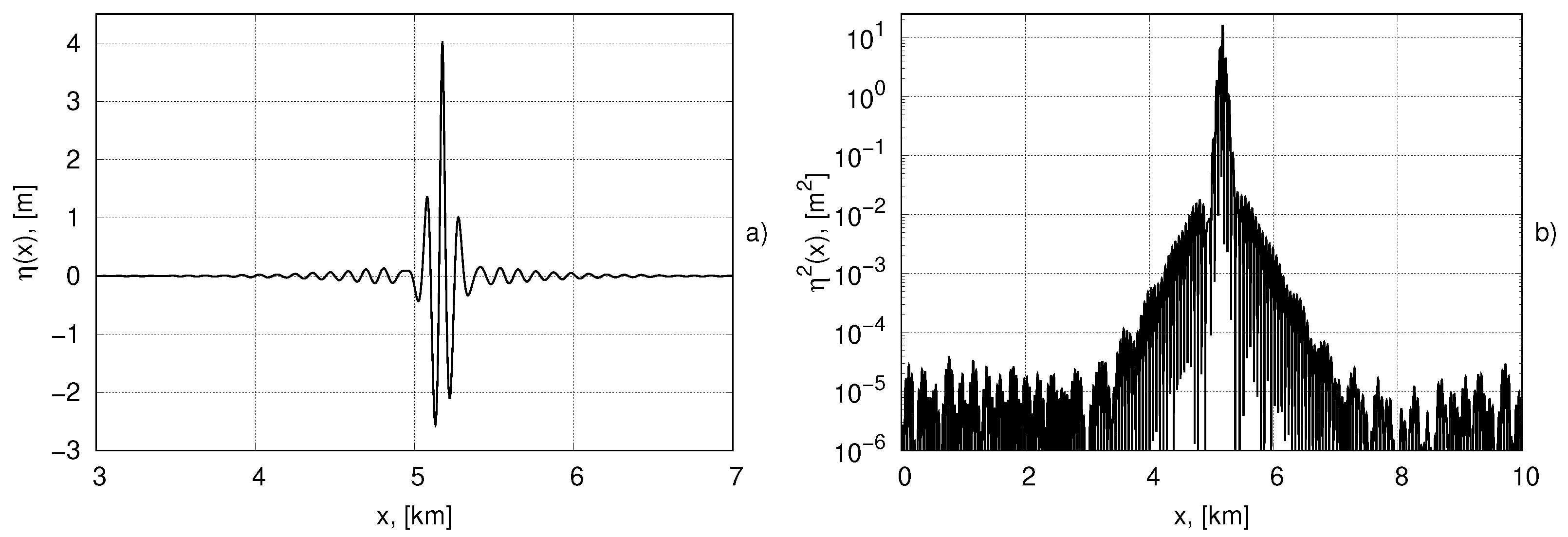

3.1. Numerical Method for Obtaining Bound Structures. Experiments with Two Breathers

3.2. Numerical Method for Obtaining Bound Structures. Experiments with Bi-Solitons of the NLSE

4. Bound Structures in the Full System of Nonlinear Equations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NLSE | nonlinear Schrödinger equation |

| SCDZE | super compact Dyachenko-Zakharov equation |

| RV (equations) | fully nonlinear equations written in conformal variables |

References

- Korteweg, D.J.; De Vries, G.X.L.I. On the change of form of long waves advancing in a rectangular canal, and on a new type of long stationary waves. Lond. Edinb. Dublin Philos. Mag. J. Sci. 1895, 39, 422–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadomtsev, B.B.; Petviashvili, V.I. On the stability of solitary waves in weakly dispersing media. Sov. Phys. Dokl. 1970, 15, 539–541. [Google Scholar]

- Boussinesq, J. Théorie des ondes et des remous qui se propagent le long d’un canal rectangulaire horizontal, en communiquant au liquide contenu dans ce canal des vitesses sensiblement pareilles de la surface au fond. J. Math. Pures Appl. 1872, 17, 55–108. [Google Scholar]

- Davey, A.; Stewartson, K. On three-dimensional packets of surface waves. Proc. R. Soc. London. Math. Phys. Sci. 1974, 338, 101–110. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, C.S.; Greene, J.M.; Kruskal, M.D.; Miura, R.M. Method for solving the Korteweg-deVries equation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1967, 19, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakharov, V.E.; Shabat, A.B. A scheme for integrating the nonlinear equations of mathematical physics by the method of the inverse scattering problem. I. Funct. Anal. Its Appl. 1974, 8, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakharov, V.E.; Manakov, S. On the complete integrability of a nonlinear Schrödinger equation. Theor. Math. Phys. 1974, 19, 551–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peregrine, D.H. Water waves, nonlinear Schrödinger equations and their solutions. ANZIAM J. 1983, 25, 16–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhmediev, N.; Eleonskii, V.; Kulagin, N. Generation of periodic trains of picosecond pulses in an optical fiber: Exact solutions. Sov. Phys. JETP 1985, 62, 894–899. [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsov, E.A. Solitons in a parametrically unstable plasma. DoSSR 1977, 236, 575–577. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.C. The perturbed plane-wave solutions of the cubic Schrödinger equation. Stud. Appl. Math. 1979, 60, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dysthe, K.B. Note on a modification to the nonlinear Schrödinger equation for application to deep water waves. Proc. R. Soc. London. Math. Phys. Sci. 1979, 369, 105–114. [Google Scholar]

- Dyachenko, A.; Kachulin, D.; Zakharov, V.E. Super compact equation for water waves. J. Fluid Mech. 2017, 828, 661–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyachenko, A.I.; Kuznetsov, E.A.; Spector, M.; Zakharov, V.E. Analytical description of the free surface dynamics of an ideal fluid (canonical formalism and conformal mapping). Phys. Lett. A 1996, 221, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyachenko, A.I. On the Dynamics of an Ideal Fluid with a Free Surface. Dokl. Math. 2001, 63, 115–117. [Google Scholar]

- Dyachenko, A.I.; Zakharov, V.E. On the formation of freak waves on the surface of deep water. JETP Lett. 2008, 88, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slunyaev, A. Numerical simulation of “limiting” envelope solitons of gravity waves on deep water. J. Exp. Theor. Phys. 2009, 109, 676–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slunyaev, A.; Clauss, G.F.; Klein, M.; Onorato, M. Simulations and experiments of short intense envelope solitons of surface water waves. Phys. Fluids 2013, 25, 067105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slunyaev, A.; Klein, M.; Clauss, G.F. Laboratory and numerical study of intense envelope solitons of water waves: Generation, reflection from a wall, and collisions. Phys. Fluids 2017, 29, 047103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachulin, D.; Dyachenko, A.; Gelash, A. Interactions of coherent structures on the surface of deep water. Fluids 2019, 4, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyachenko, A.I.; Kachulin, D.; Zakharov, V.E. On the nonintegrability of the free surface hydrodynamics. JETP Lett. 2013, 98, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petviashvili, V.I. Equation of an extraordinary soliton. FizPl 1976, 2, 469–472. [Google Scholar]

- Dyachenko, A.; Kachulin, D.; Zakharov, V.E. Envelope equation for water waves. J. Ocean. Eng. Mar. Energy 2017, 3, 409–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachulin, D.; Gelash, A. On the phase dependence of the soliton collisions in the Dyachenko–Zakharov envelope equation. Nonlinear Process. Geophys. 2018, 25, 553–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachulin, D.; Dyachenko, A.; Dremov, S. Multiple Soliton Interactions on the Surface of Deep Water. Fluids 2020, 5, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabat, A.; Zakharov, V. Exact theory of two-dimensional self-focusing and one-dimensional self-modulation of waves in nonlinear media. Sov. Phys. JETP 1972, 34, 62. [Google Scholar]

- Zakharov, V.E. Stability of periodic waves of finite amplitude on the surface of a deep fluid. J. Appl. Mech. Tech. Phys. 1968, 9, 190–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korotkevich, A.; Pushkarev, A.; Resio, D.; Zakharov, V.E. Numerical verification of the weak turbulent model for swell evolution. Eur. J. Mech. B/Fluids 2008, 27, 361–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyachenko, A.; Kachulin, D.; Zakharov, V.E. Collisions of two breathers at the surface of deep water. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2013, 13, 3205–3210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frigo, M.; Johnson, S.G. The design and implementation of FFTW3. Proc. IEEE 2005, 93, 216–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kachulin, D.; Dremov, S.; Dyachenko, A. Bound Coherent Structures Propagating on the Free Surface of Deep Water. Fluids 2021, 6, 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/fluids6030115

Kachulin D, Dremov S, Dyachenko A. Bound Coherent Structures Propagating on the Free Surface of Deep Water. Fluids. 2021; 6(3):115. https://doi.org/10.3390/fluids6030115

Chicago/Turabian StyleKachulin, Dmitry, Sergey Dremov, and Alexander Dyachenko. 2021. "Bound Coherent Structures Propagating on the Free Surface of Deep Water" Fluids 6, no. 3: 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/fluids6030115

APA StyleKachulin, D., Dremov, S., & Dyachenko, A. (2021). Bound Coherent Structures Propagating on the Free Surface of Deep Water. Fluids, 6(3), 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/fluids6030115