Abstract

As the global population grows, the demand for cost-effective and eco-friendly water purification methods is increasing, which presently is at its peak due to the increase of impurities in water and the increasing awareness of waterborne disease. Carbon-based materials, which includes activated carbon, carbon nanotubes (CNTs), graphene, graphene oxide (GO), reduced graphene oxide (rGO), fullerene, and carbon dots, are observed as potential candidates for water treatment. In the present review, developments related to water purification methods using carbon nanomaterials over the last decade are critically summarized, with an emphasis on their thermophysical properties. The fabrication techniques for activated carbon, CNTs, graphene, and graphene oxide are presented, with an emphasis on the properties of carbon materials that allow their usage for water purification. Then, an extensive review of 71 patents dedicated to water purification using carbon materials such as activated carbon and cotton fibers is performed. Subsequently, the more important research studies on water purification using carbon nanomaterials are discussed, showing that CNTs, GO, and rGO are widely used in water treatment processes. The present review critically discusses the recent developments and provides important information on water purification using carbon materials.

1. Introduction

Water is the most abundant and irreplaceable resource available globally, however despite its importance, water scarcity is occurring due to the rapid increase in the global population, intense industrialization, stringent water quality standards, and negative climate change [1]. Contamination with heavy metals (arsenic, iron, lead, mercury, chromium), microbes (Escherichia coli, Staphylococus), biological compounds, and other components (fluoride, cadmium) is widely encountered as major challenge related to water purification technology [1,2,3]. The rising challenge of pure water availability is reflected in UN models that project that 1.8 billion people will face water scarcity by 2025. This is why the problem of water scarcity is listed in the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) [2,4].

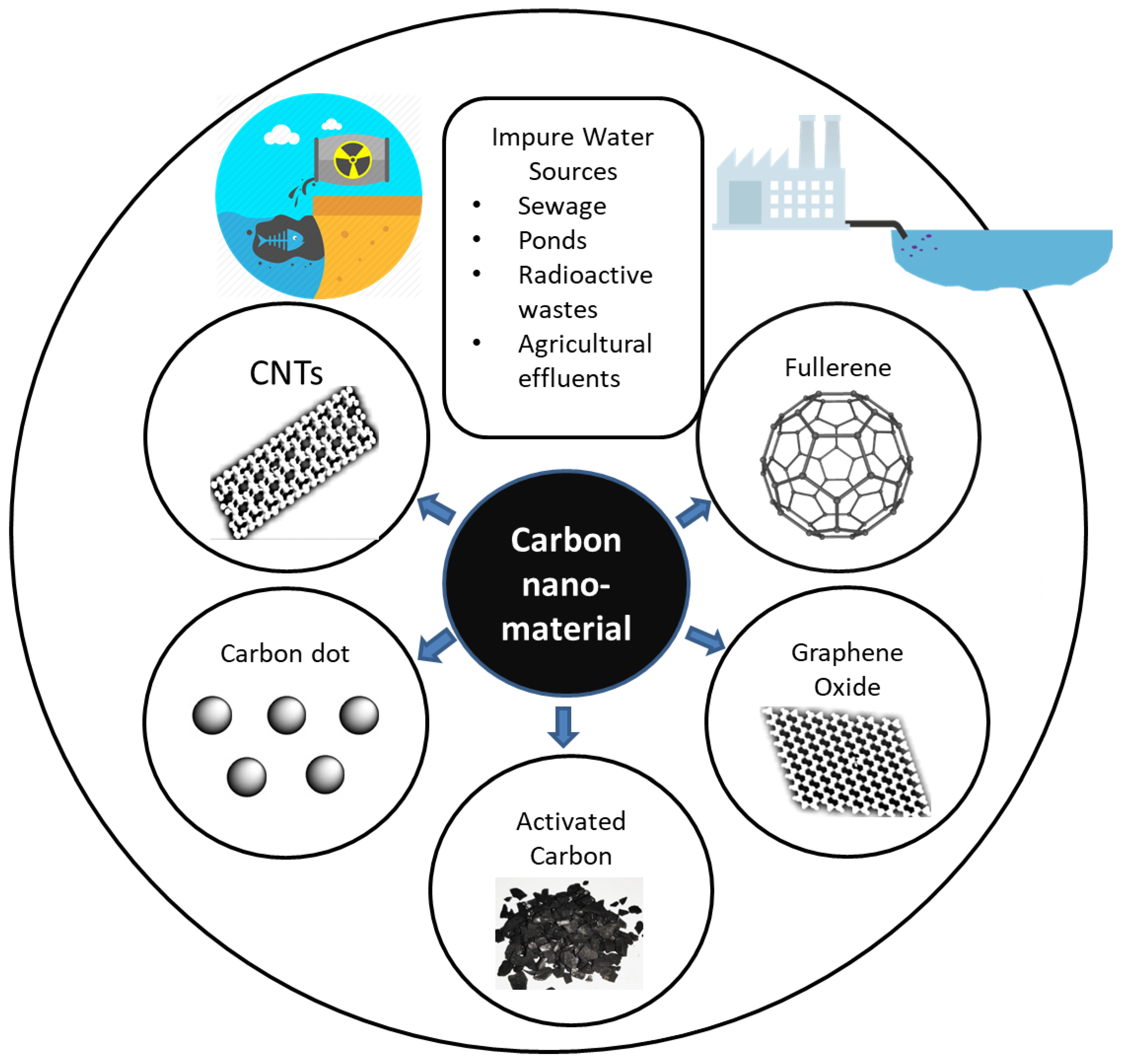

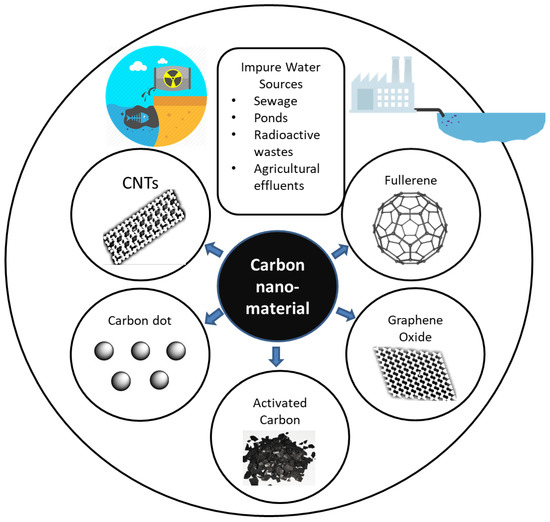

Conventional water treatment includes absorption, membrane filtering, and distillation processes [2,3,4]. Industrial effluent, agricultural waste water, sewage, and radioactive waste water are sources of contamination, as shown in Figure 1. Carbon nanoparticles can potentially be used for technological innovation in terms of improving water treatment due to being eco-friendly and cost-effective [5] and because of their specific surface area, strong sorption, fast kinetics [1], thermal stability, and conductivity [2,6,7]. Single-walled and multiwalled carbon nanotubes (CNTs, MWCNTs), graphene, and fullerene are among the most popular examples of carbon nanoparticles [1]. Graphene has been one of the most widely tested materials for water purification technology since its discovery in 2010 [4].

Figure 1.

Use of carbon for water purification. CNTs, carbon nanotubes.

The structural properties of carbon nanomaterials such as CNTs, graphene oxide, carbon dots, fullerene, and activated carbon are largely responsible for their use in water purification technology. However, they also have some other additional characteristics that make them potential candidates. For example, the electrically conductive and selective ion transfer properties of CNTs could be important for desalination [8]. Additionally, 2D graphene is a versatile absorbent due to its high affinity to target contaminants because its surface functional groups, which are present on single sheets of carbon, are utilized to absorb heavy metals [6]. The formation of hierarchically structured layers allows absorption of heavy metals due to the formation of mesopores within the walls of the macropores [9]. Liu et al. [10] synthesized L-cysteine-functionalized MWCNTs for selective sorption of heavy metals and observed that the use of MWCNT–cysteine allows effective sorption of cadmium.

Activated carbon is a widely used material in existing water purification systems [11,12,13,14,15,16], due to its cost-effectiveness and availability. However, it has limited removal efficiency due to its low specific surface area, lower number of active sites, non-selectivity, and low absorption kinetics [17]. Activated carbon is a highly porous material with a heterogeneous range of pores (measuring approximately <2 nm in diameter) that are present all around its internal structure [18]. These pores increase the specific surface area to up to 2500 m2/g [19]. Typically, activated carbon is made up of 80% carbon, with the remaining 20% composed of other elements such as oxygen and nitrogen [20,21].

CNTs are promising materials, as they are able to generate size-exclusion membranes, and due to their nanoscale features are capable of blocking the transport of certain microorganisms across these membranes. The main advantage of this is that the membranes can effectively filter bacteria from aqueous solutions, where the amount of CNT loading also has an effect on the virus filtration capacity [22]. An epoxy-entrapped, vertically aligned CNT material displayed similar antibiofouling properties, with physical damage and oxidative stress to microorganisms proposed as the mechanisms of action [23]. A more direct approach for fabricating antibacterial CNT water purification membranes was achieved with the incorporation of the natural bactericide nisin through adsorption onto CNTs [24]. The nisin-adsorbed CNTs were then coated onto a polycarbonate filter membrane, where bacteria become entrapped and are then neutralized. This approach provides a treatment method for nanometer-range bacteria.

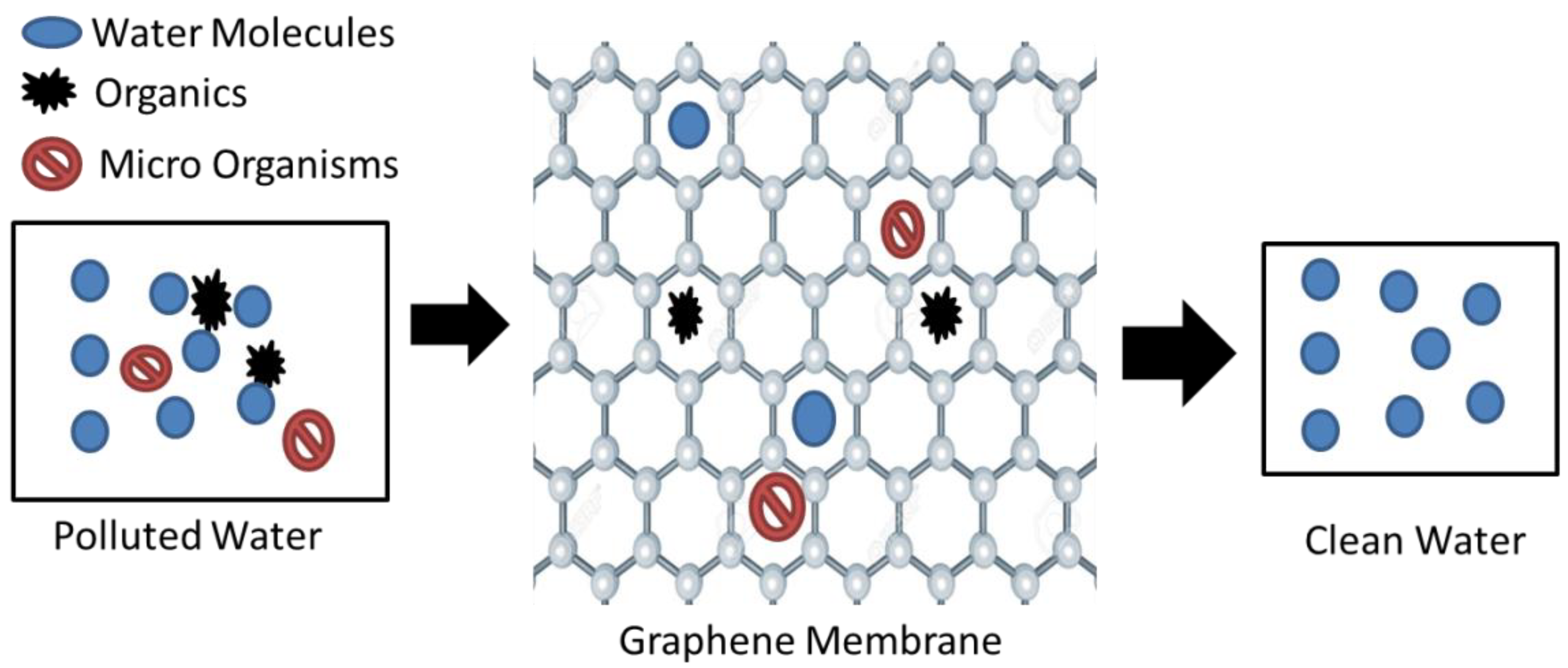

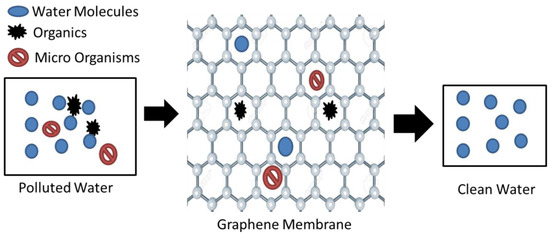

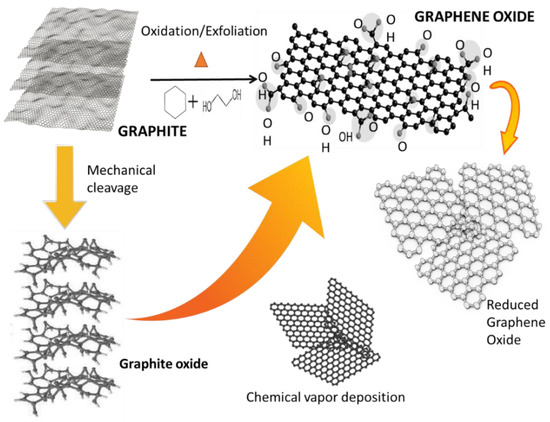

Graphene oxide (GO) and reduced graphene oxide (rGO) are the two main derivatives of graphene [25]. Graphene oxide (GO) acts as a promising sorbent, having the ability to efficiently remove heavy metals and radionuclides. GO has attracted attention within the research community due to its extremely powerful separation ability. The presence of -OH, -COOH, -C=O, and other hydrophilic groups is the possible reason for this [26,27]. The highly functionalized operative surfaces of GO give it the potential to remove pollutants from water, as displayed in Figure 2 [28]. It can be observed that the graphene structure is only permeable to water molecules, and hence filters out impurities.

Figure 2.

Graphene water purification method [28].

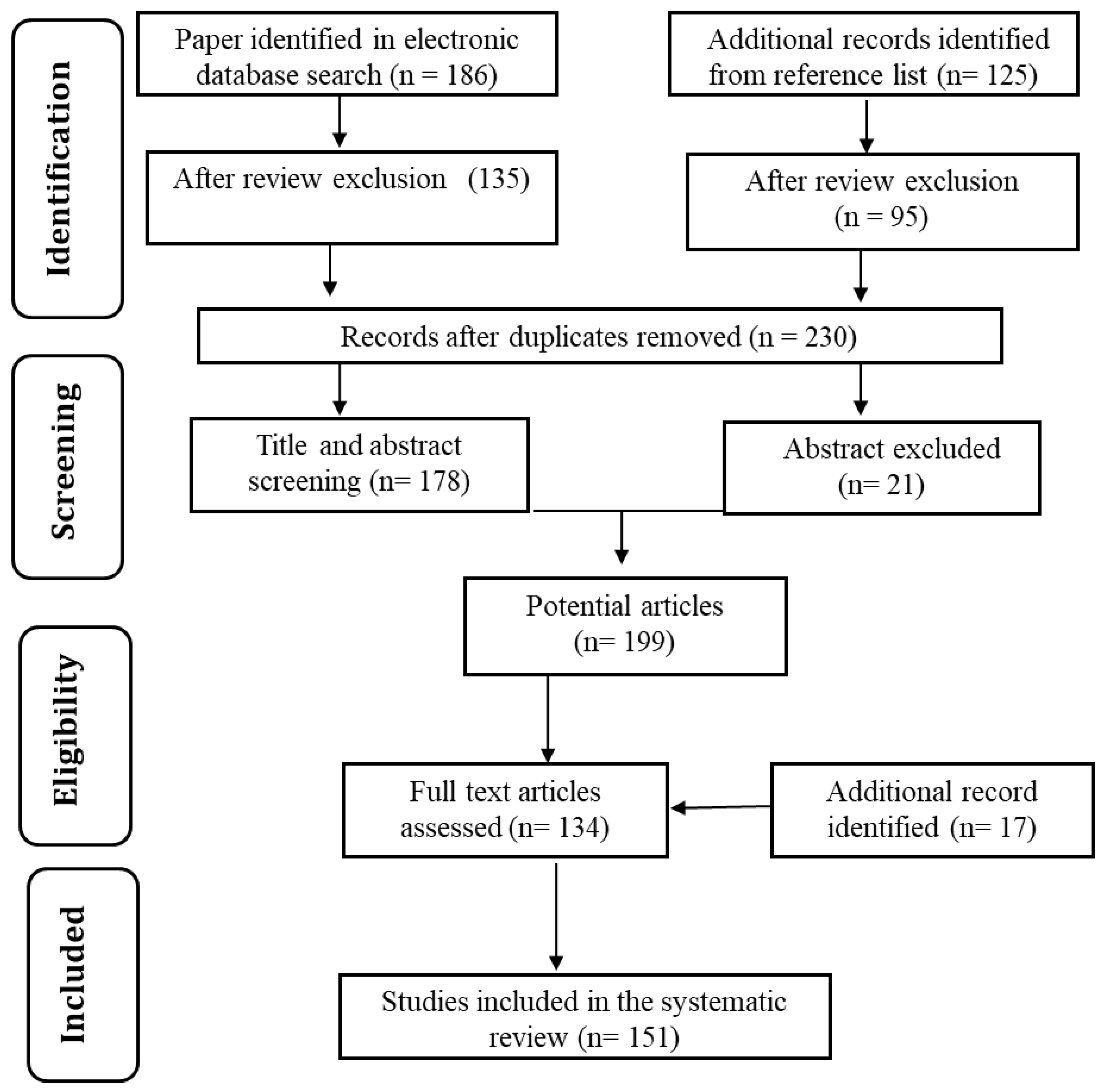

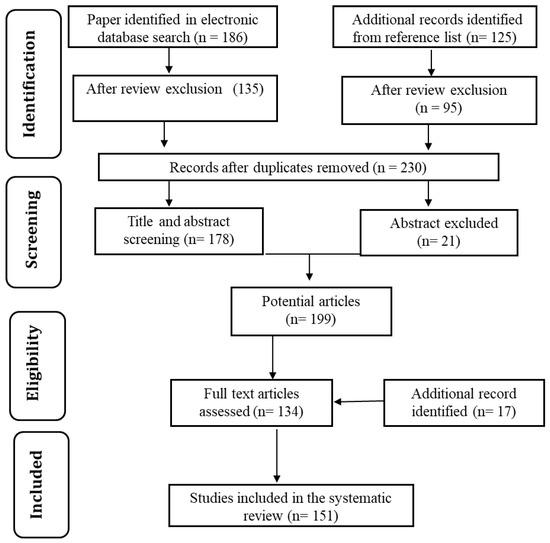

The vast technological advancements in water purification methods and significant contributions of carbon materials motivated us to prepare a detailed review of the topic. In order to keep the paper focused, the most appropriate articles were selected from Google Scholar, PatSeer, Scopus, and Science Direct databases. Combinations of keywords such as “water purification” and “carbon nanoparticles” were used. The focus was on studies published in the last decade. The date of the last search was 8 November 2020. Figure 3 shows the flow chart for relevant research article identification and selection. The selection of relevant articles was performed in two stages, as below.

Figure 3.

Flowchart of identification and selection strategy used for research articles.

- In the initial stage, the bibliographies were searched according to the article title and abstract. Moreover, relevant patents were identified based on the title and claim. Articles were filtered to meet the following three basic topic criteria: (a) water purification; (b) use of carbon nanoparticles; (c) subject related to cost-effective and eco-friendly technology. Additional papers were also searched from articles’ reference lists. After review and exclusion of the database sources, 230 studies remained.

- In the second stage, the studies were read in full to identify the most relevant studies. Patents were also examined to identify the most appropriate ones. This process led to a final number of 151 potential studies.

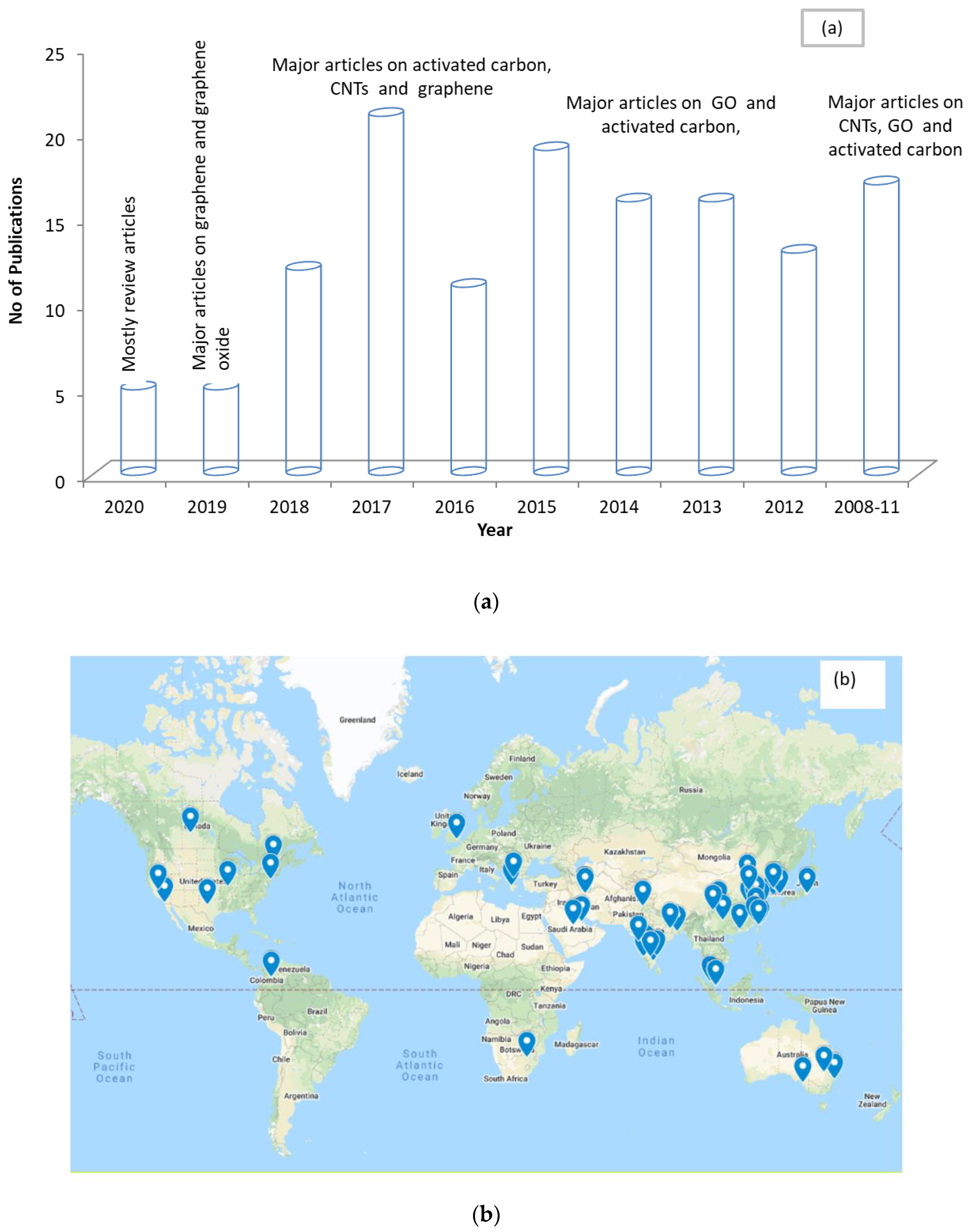

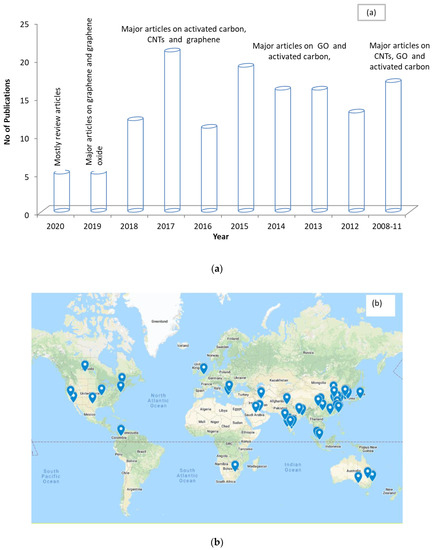

Figure 4a,b shows the chronological distribution of the recent publications and the geographical locations of the contributing authors for articles relating to water purification involving carbon-based nanoparticles. It can be observed that activated carbon, CNTs, and graphene are the most used carbon materials. This reflects the increase in attention from the research community towards testing carbon-based nanoparticles in water purification systems. Additionally, it can be observed that the researchers in this field are spread globally.

Figure 4.

Representation of publications by year (a) and geographical location (b) from 2010–2020 for articles on water purification using carbon nanoparticles.

Carbon-based materials are gaining popularity due to their superior structural properties, ease of handling, eco-friendly nature, and cost-effectiveness. They are widely recommended for adsorption-based water purification methods due to their renewable nature [29]. The innovative use of carbon materials for water purification technologies is one of the focus areas within the research community, which can be observed from the 71 patents included in the present review. Carbon materials are used both alone and in composite structures, with fiber (basalt fiber) often used to improve the effectiveness [30,31]. Han et al. [32] prepared CNT-based photothermal nanocomposites and observed improved water purification via solar steam generation. Li et al. [33] prepared super-aligned carbon-nanotube-activated carbon composite electrodes and observed improvements in the water distillation capability. Among the articles, physical absorption, photodegradation, and solar-driven evaporation processes are widely studied [34]. The recent review on carbon-based nanoparticles for water purification provides insights on heavy metal removal [35], osmosis membranes [36], and carbon material properties [37]. The present review covers recent articles and patents related to water purification using carbon materials.

The present study reviews the recent developments in water purification technology using carbon materials. The initial section discusses carbon nanomaterial fabrication. The next section covers patents related to water purification using carbon materials from the last decade. It provides insights into recently developed water purification technologies. Further, recent research articles on water purification using activated carbon, CNTs, graphene, graphene oxide, and other carbon materials are discussed.

2. Carbon Nanomaterial Fabrication

Nanotechnology has emerged at the forefront of science and technology development. Carbon-based nanomaterials such as activated carbon, CNTs, graphene, carbon dots, and fullerene are major building blocks of this new technology. Due to their unique combination of electrical, thermal, and mechanical properties, the interest of the scientific community in potential applications of carbon nanomaterials in composites, electronics, computers, hydrogen storage, drug delivery, sensors, and many other related areas has grown rapidly [19,31].

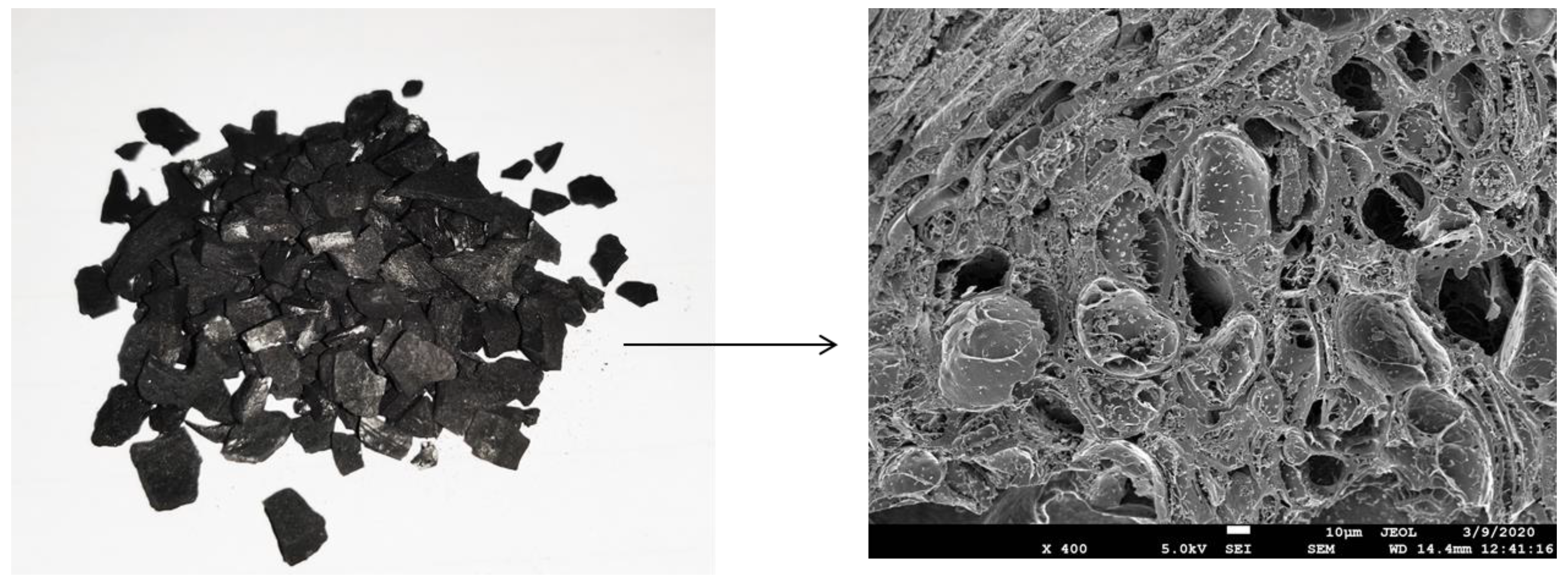

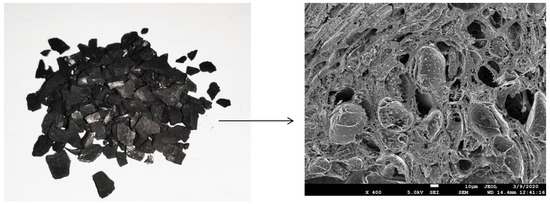

Activated carbon is formed from carbonaceous materials (bamboo, eucalyptus, lignite, coconut shell and husk), which makes it cost-effective, and hence widely used in water purification technology [19,28]. Figure 5 shows the granular activated carbon with its corresponding FESEM image. It can be observed that macropores are visible on its surface. In general, activated carbon is a crude form of graphite with a highly porous structure, containing pores of various sizes. It has a large number of cracks and crevices at the molecular level, which greatly increase its surface area. Activated carbon has an internal surface area of up to 1500 m2/g. This enables activated carbon to carry out a phenomenon called adsorption, in which the molecules of a liquid or a gas are trapped by the internal or external surface of a solid. The structure of activated carbon is almost similar to that of pure graphite, since the C-C bonds hold the hexagonal layers in the activated carbon molecules. The graphite crystals are composed of layers of fused hexagons held by weak van der Waals forces. The pore structure develops in the activated carbon, and thus the final properties of the activated carbon mainly depend on the raw materials and the production process [38].

Figure 5.

Macropores in activated carbon.

Do et al. [28] formed an activated carbon–Fe3O4 nanoparticle composite for water treatment. This composite provided the combined features of activated carbon (absorption) and Fe3O4 nanoparticles (magnetic with catalytic properties). They used a coconut-shell-based powdered activated carbon. The presence of Fe3O4 nanoparticles in the pores of the activated carbon allows easy manipulation of the super paramagnetic properties. The authors observed the easy regeneration of the composite by washing with hydrogen peroxide due to the presence of Fe3O4, meaning it can be used repeatedly. The activated carbon–Fe3O4 nanoparticle composite is a potential absorbent catalyst that could be used for the removal of organic compounds, however its absorption capacity is gradually reduced with repeated regeneration.

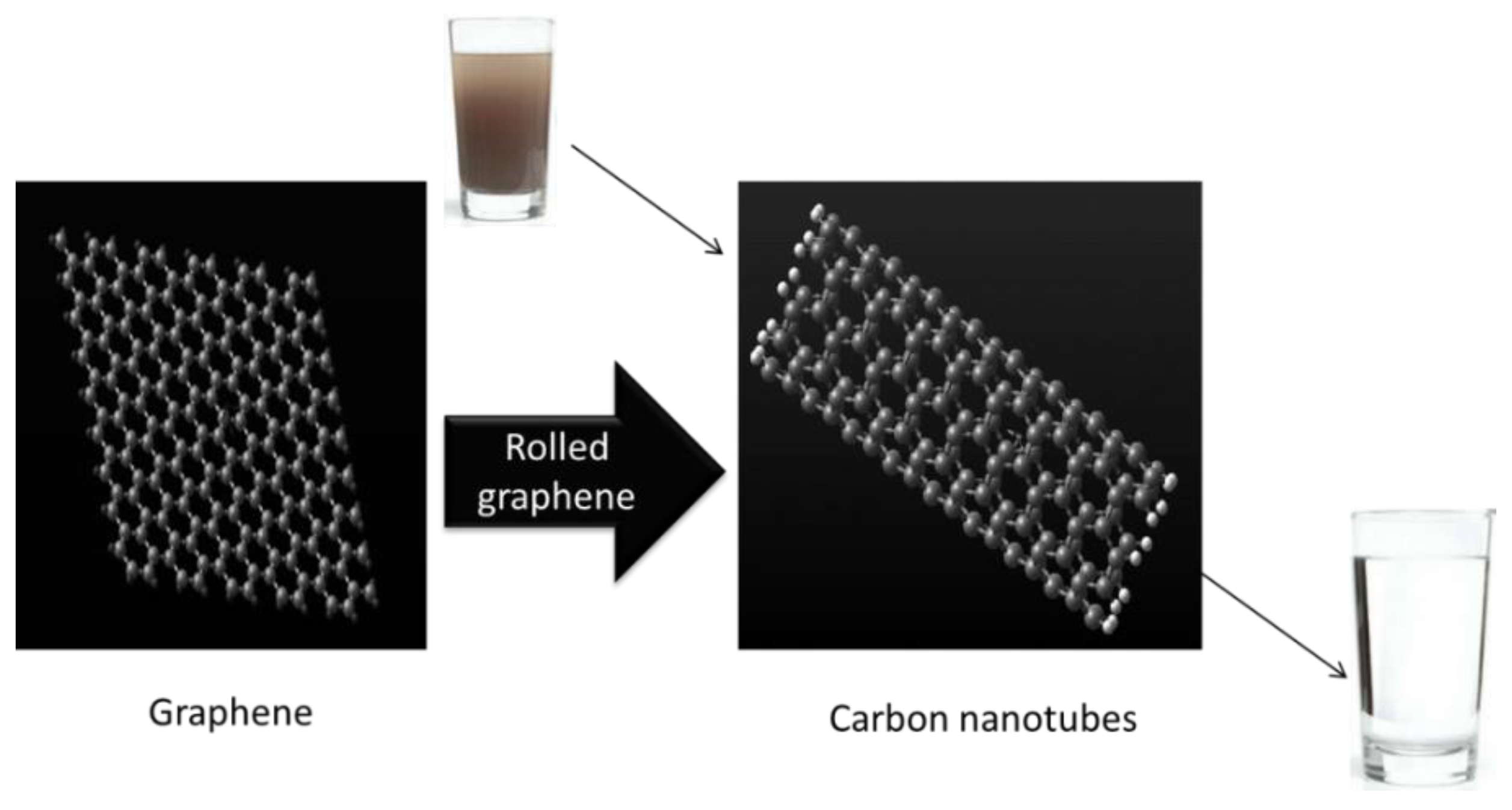

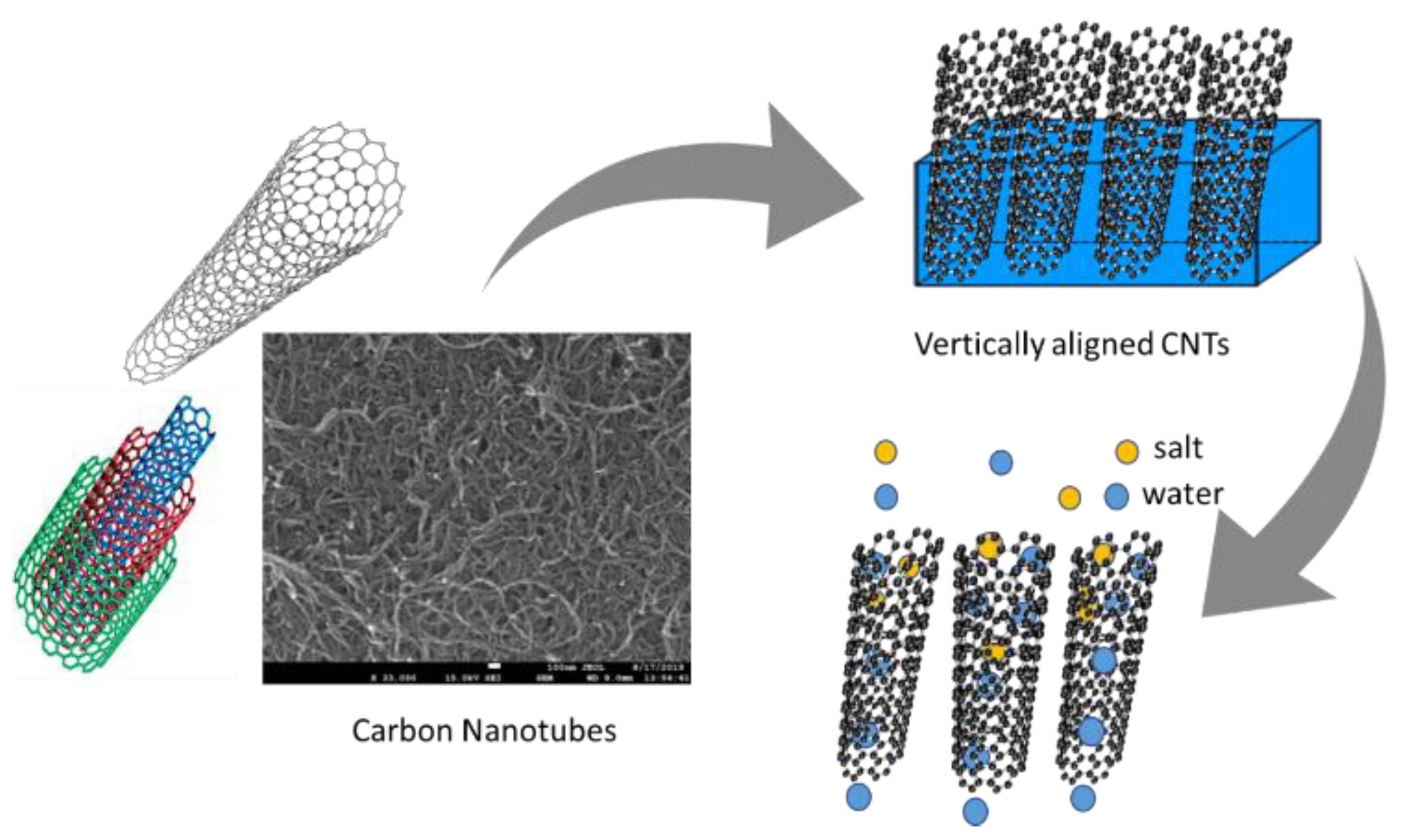

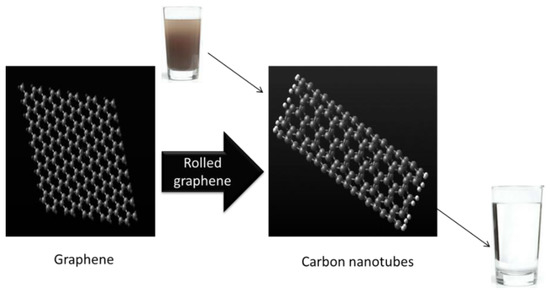

A carbon nanotube can be considered as a graphene sheet that has been rolled up to make a seamless cylinder with a diameter as small as 0.4 nm, with a length of up to a few centimeters, and half of a fullerene molecule in each end as a cap. CNTs come in various forms, such as single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs), double-walled carbon nanotubes (DWCNTs), and multiwalled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs). SWCNTs consist of a single sheet of graphene forming a cylinder, as shown in Figure 6. The small diameter of CNTs means they are impermeable to impurities and makes them able to purify water. DWCNTs consist of two such cylinders in a concentric arrangement, whereas MWCNTs consist of an array of concentric cylinders that are positioned at a distance of 0.35 nm from each other. There are various ways to define the structure of carbon nanotubes. One possibility is to consider that CNTs may be obtained by rolling a graphene sheet in a specific direction, maintaining the circumference of the cross-section [39]. Since the microscopic structure of the CNTs is closely related to graphene, the tubes are usually labelled in terms of graphene lattice vectors. Two types of carbon nanotube (CNT) membranes can be fabricated, namely (i) vertically aligned (VA) and (ii) mixed matrix (MM) CNT membranes [40].

Figure 6.

Use of CNTs for water purification.

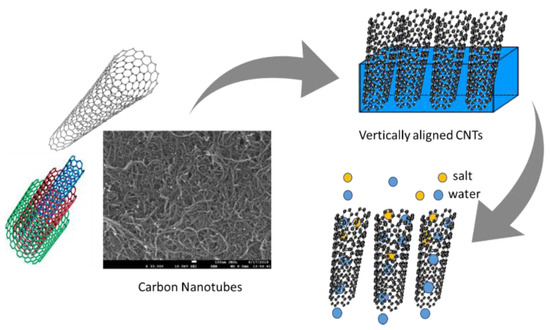

Vertically aligned carbon nanotube (VA-CNT) membranes are synthesized by arranging perpendicular CNTs with supportive filler contents between the tubes, as shown in Figure 7 [25]. These membranes are molecular sieves with an intercalated filler matrix such as a polymer between them. The fillers may be epoxy, silicon nitride, or plastic resins with no water permeability. The fabrication procedure is simple but the pore sizes are irregular, means membranes are not able to retain Ru (NH3)63+ ions initially following H2O plasma and HCl treatments. However, in a previous study, functionalization of a CNT core with negatively charged carboxylate groups trapped the positively charged Ru (NH3)63+ ions [41]. The synthesis of homogeneous CNT membranes using laser vaporization, arc discharge, and pyrolysis is challenging due to the difficulty of controlling the diameter, length, and chirality. The chemical vapor deposition (CVD) approach is probably the best method for synthesizing VA-CNT membranes [42]. The use of catalysts in the CVD method ensures uniform CNT membranes of 20–50 nm in diameter and 5–10 μm in length [43].

Figure 7.

Schematic of CNT membrane fabrication [25].

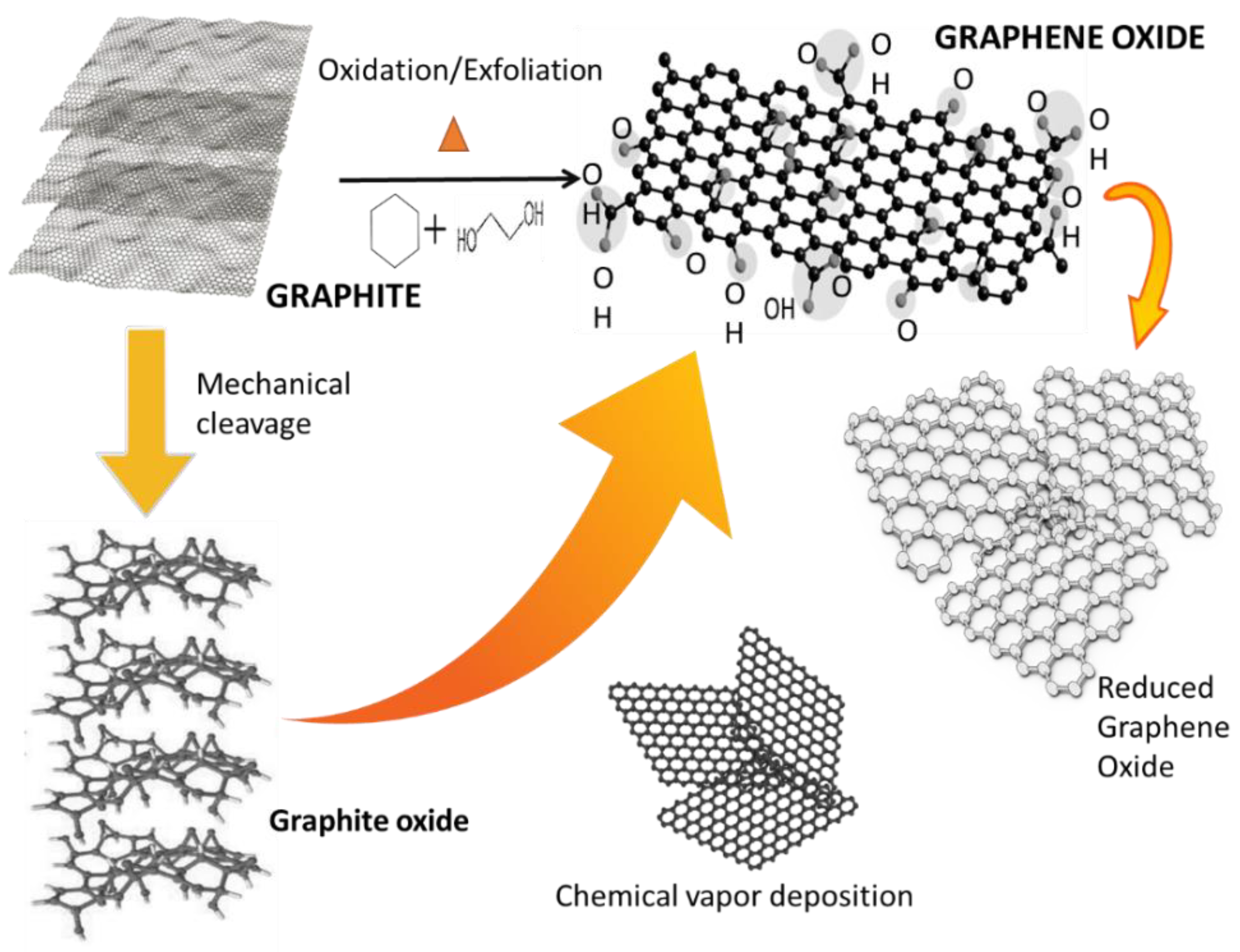

Graphene oxide (GO) can be regarded as a typical two-dimensional oxygenated planar molecular material, with sp2 carbon atoms in a honeycomb structure [30]. GO is a non-stoichiometric chemical compound comprising carbon, oxygen, and hydrogen in a variable ratio, which largely depends on the processing methodologies [30]. It possesses abundant oxygen functional groups that are introduced into the flat carbon grid during chemical exfoliation, which present as oxygen epoxide groups (bridging oxygen atoms), carbonyl (C=O), hydroxyl (-OH), phenol, and even organo sulfate groups. Figure 8 shows theoretical models of the structure of graphite or graphene oxide [31]. In 1936, Hofmann and Rudolf [44] proposed the first GO structure, in which numerous epoxy groups were randomly distributed on a graphite layer. In 1946, Ruess [45] updated the Hofmann model by incorporation hydroxyl entities and alternating the basal plane structure (sp2 hybridized mode) with an sp3 hybridized carbon system (where s & p are atomic orbitals).

Figure 8.

Theoretical models of the structure of graphite or graphene oxide [31].

In 2013, Dimiev et al. [30] revisited the structure via acid titration and ion exchange experiments in terms of the acidity of GO and proposed a novel dynamic structural model (DSM), which describes the evolution of several carbon structures with attached water molecules beyond the static Lerf–Klinowski (L-K) model. Amongst these models created from 1936 through to 2018, the L-K model has become the accepted basic model due to its interpretability for the majority of experimental data and ease with which it can be further adapted. However, knowledge about the structure of GO is still an ongoing argument.

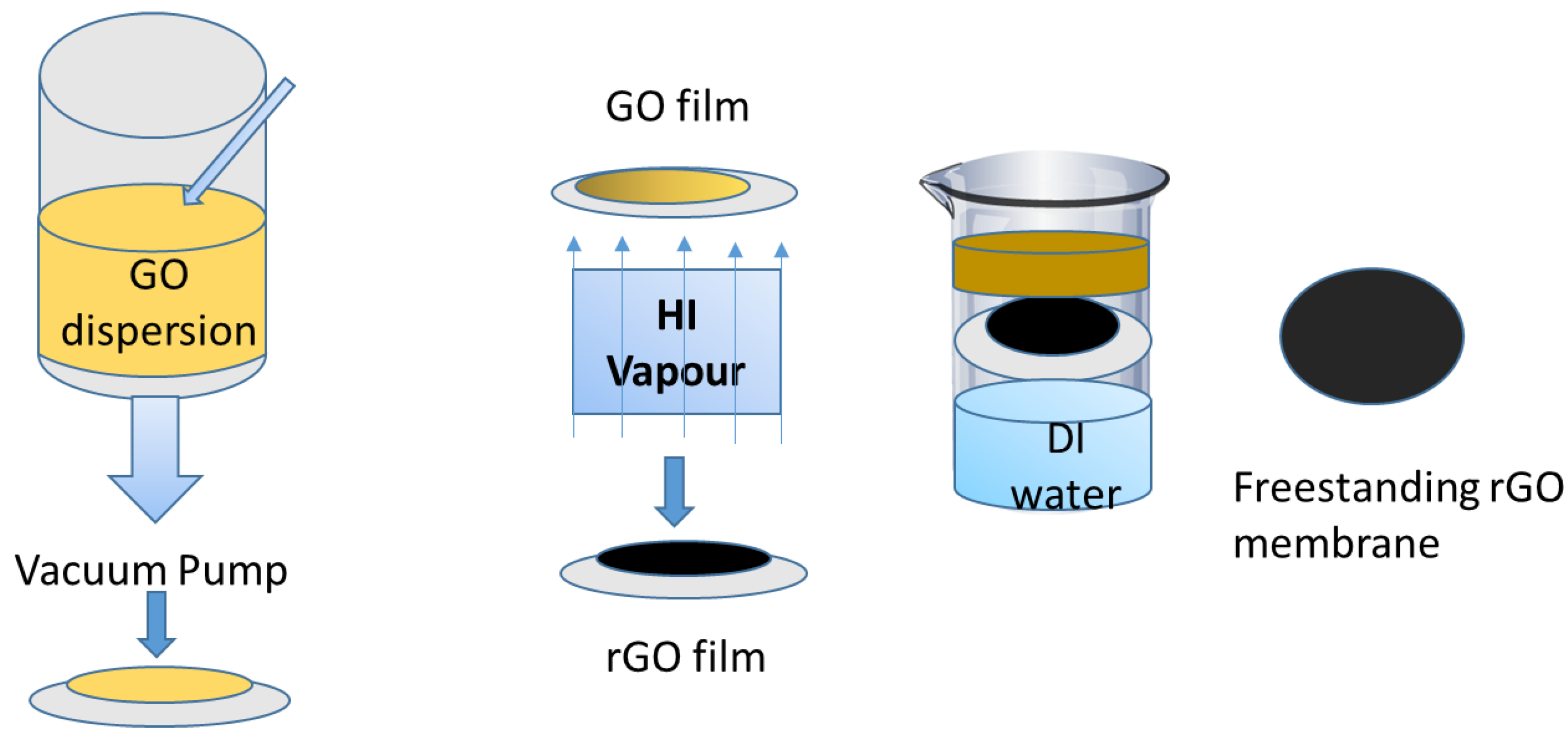

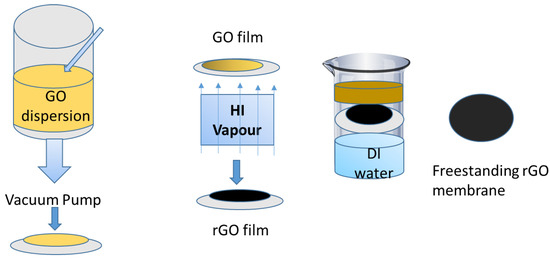

Fabrication of graphene oxide (GO) membrane: A simplistic and efficient method for fabricating ultrathin reduced graphite oxide (rGO) membranes is shown in Figure 9. A modified Hummer’s method is first used for the synthesis of the GO nanosheets measuring several micrometers in diameter [46]. A supported GO membrane is then formed on a mixed cellulose ester (MCE) filter by straining a diluted GO dispersion. This filtration method is not only simple and highly reproducible, but also allows precise and accurate control of the thickness of the GO layer [47]. Figure 9 shows the fabrication of rGO and its use for water purification. The color of the GO membranes formed on the MCE filter is light yellow. The resultant GO–MCE membrane is then placed above a hydriodic acid (HI) solution. Within 2–3 min, the GO membrane will quickly turned black, indicating that GO has reduced to rGO using HI vapor. Later, the rGO–MCE membrane is placed on the water’s surface. Within 1 min, spontaneous separation of the rGO membrane from the MCE filter will be achieved. The MCE filter will sink to the bottom, while the ultrathin rGO membrane will float on the water’s surface [48].

Figure 9.

Fabrication of reduced graphite oxide (rGO) for water treatment [48].

3. Recent Patents for Water Treatment Using Carbon Material

This section explores the recent patents for water treatments using carbon materials. Activated carbon, GO, rGO, CNTs, fullerene, carbon dots, and carbon composites are widely used to develop and improve water purification technologies. This is reflected by the number of patents that integrate processes and technologies for use in small- and large-scale water purification. Table 1 lists patents related to water purification using carbon-based particles.

Table 1.

Patents for water purification technologies involving carbon-based particles.

Patent CN109502896A [49] involves a water purifier that use graphene in membrane form along with polypropylene cotton, which can successfully remove impurities ranging from iron rust to dust. Patent CN107265530A [50] is a multiple-effect water purifier that utilizes acrylamide-oligomer-grafted oxidized graphene for purification, using processes such as flocculation and filtration to remove phenyl compounds and heavy metal ions. Patent CN108002366A [51] uses graphene in a completely different form, whereby a new kind of graphene water cleaning foam was made using solar energy, which can evaporate the moisture present in sewage using solar radiation, with a very high ion removal rate (>99.5%) and high bacteria removal rate (>99.9%), meeting drinking water standards.

Patent US3612279A [52] involves a device containing four large perforated tubes wrapped with filter cloth coated with a mixture of activated powdered carbon, diatomaceous earth, and fibers. The four tubes are inserted into a tank fed at the bottom with impure water, which passes through the filter cloth, entering the tubes through perforations. Each of these tubes is connected on top, then finally a union pipe serves as an outlet for the filtered water. In this process, materials such as rust, sediment, chlorine, and other undesirable substances are left outside the tank. Patent US2014166591A1 [53] involves a water filter that utilizes granulated active carbon, along with two other technologies—ultraviolet “C” (UVC) and photocatalytic oxidation (PCO). In the beginning, the granulated active carbon particles are coated with titanium dioxide, which turns all of the surfaces into powerful semiconductors, triggering a powerful PCO process when UVC photons come into contact with them. The carbon particles absorb the organic compounds, while the other technologies finish the oxidation process. Additionally, this process can regenerate the carbon particles endlessly. Patent W02010144175A1 [54] involves a design in which activated carbon is used in the filtration mesh. The main objective of this design is to decrease the content of leachable arsenic present in water, which can be toxic if consumed. To achieve this, an adsorbent for leachable arsenic is introduced within the carbon particles at a concentration of less than 5%. Tianye [55] developed an active carbon filter using active carbon from bamboo, along with other chemicals such as sodium hydroxide, potassium hydroxide, octadecyl acrylate, bentonite, and silicon dioxide. It contained a natural antibacterial agent that was added into the active carbon material. The filter process was economical, had a large absorption capacity, and did not create any secondary pollution.

Patent CN106830474A [56] involves a water purification system that can be used for healthy wine production using various filtration methods and processes. It contains an ultraviolet sterilizer, ultrafiltration membrane, precision filter, and an active carbon filter. All of these steps and processes are connected and the water is filtered through these systems. Patent CN109081477A [57] involves another filter that can be used for rural water supply and purification systems using a heavy metal ion treatment system, a water softening system, an activated carbon filter system, and adsorption layers that utilize graphene oxide, KDF55 alloy, and polyacrylic acid. It is claimed that the filter can purify toxic organisms and compounds and is easy to operate.

Patent CN10304386AJ [58] involves a three-stage filter that is used to tackle the problem of water loss and weak acid water production, which were the problems created by the filters currently available in the market. Therefore, the first stage involves microfiltration, as well as a composite molecular sieve; the second phase involves spherical preparation using active carbon and spontaneous medium-distance infrared rays; the last stage involves a nanofiltration membrane. Due to the requirement of low pressure, the absence of a pump saves energy. This design also manages to preserve water resources as intended. Patent CN209361991U [59] is a design for a household filter with an easy-to-replace activated carbon filter element. The design aims to eliminate the inconvenience faced by consumers by using a handy filter. Patent CN107298506A [60] involves an active carbon filter, wherein the purifier body is divided into a filtering cavity and an absorbing cavity, with the stirrers located in the filtering cavity. In the adsorbing cavity, numerous active carbon spheres are placed. The aim is that stirrers will speed up the water purification process.

4. Recent Research Papers on Water Purification Using Carbon Material

Access to pure drinking water is of the utmost importance for a healthy life. The search for eco-friendly and cost-effective methods for water purification has been a research priority for a long time. The increasing contamination (microorganism, chemicals, sediments, organic residuals) has made the research community accelerate its efforts. The use of carbon-based materials (activated carbon, CNTs, graphene, fullerene nanoparticles) for water purification has been widely investigated by research communities in the last decade, as observed from Table 2.

Table 2.

Studies on water purification.

Nasrabadi and Foroutan [4] observed that CNTs have the potential to act as nanoelectrodes for separation of Na+ and Cl− ions. They observed the nanoscale water purification (desalination) potential of CNTs using molecular dynamics simulations. The external electric field makes the Na+ move towards negatively charged CNTs and vice versa, leading to desalination. This study displays the potential applications of CNTs as efficient desalination nanomaterials. Ntim and Mitra [119] proposed a multiwalled carbon nanotube–zirconia (MWCNT-ZrO2) nanohybrid for use in the removal of arsenic traces in water. The MWCNT-ZrO2 nanohybrid absorbs AS(V) faster than AS(III). One of the major advantages is that the adsorption capacity is not a function of pH. The adsorption rate of arsenic is two to three times slower than iron-coated MWCNTs, however the capacity is two to five times higher than iron-coated MWCNTs.

Beobide et al. [120] stated that industrial waste water contains highly biodegradable compounds. Due to these highly biodegradable compounds, it is not effective to use a membrane bioreactor (MBR) alone, so it is used in combination with nanofiltration or reverse osmosis. Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) is used to measure the level of methyl blue (MB). MB is used in the textile industry as an aromatic dye. At a concentration of 500 ng/mL it affects the human nervous system. By using CNTs, there was a clear reduction in MB at 1622cm−1. Bakajin et al. [121] used CNTs in their initial experimentation stage by considered the three important factors i.e. capital, energy and operational cost. CNTs have a uniform pore size, which eliminates the need for multistage pretreatment efforts. The membrane surfaces of CNTs are hydrophilic, making cleaning easy using backwashing or rinsing. Das et al. [122] stated that due to a lack of fresh water for daily usage purposes, CNTs were used for filtration, as they can remove the pollutants and salt from water. The usage of CNTs in water is becomes more effective than other conventional options due to the low energy consumption and antifouling and self-cleaning properties (CNT membranes have a self-cleaning capacity).

Masinga et al. [123] discussed the synthesis of nanocomposites of β cyclodextrin polymers and nitrogen-doped carbon nanotubes under microwave irradiation. The polymers synthesized in the microwave showed better results in the removal of PnP from water than the conventional polymers. Zhang et al. [124] outlined a construction strategy for porous TiO2 nanotube carbon macroscopic monoliths (TNCMs). This material not only has a large surface area, porosity, and optical properties, but is also advantageous due to its adsorption properties and use of photocatalytic materials. TNCMs can be reused due to their robustness, facilitating organic waste water purification.

Nguyen-Phan et al. [125] prepared reduced graphene oxide–titanate (rGO-Ti) hybrids by including spherical TiO2 nanoparticles with graphene. The RGO sheets were used as a platform for the deposition of titanate, which showed much better results compared to pure materials. Sreeprasad et al. [5] showed a simple synthetic process for rGO–metal oxide composites and outlined their water purification applications. The primary cause for composite formation is the reaction between the rGO and metal precursor. The composites are used in water purification and can also be used in engineering and science fields, such as in catalysis and for fuel cells.

Peng et al. [126] worked on the removal of arsenate from water. The authors synthesized GO-FeOOH composites, showing excellent absorption of arsenate from water. This experimental procedure showed the three-dimensional matrix method is less efficient than using two-dimensional GO sheets. Sun et al. [127] fabricated graphene oxide–silver nanoparticles (GO-AgNPs) onto cellulose acetate (CA). In the filtration process, GO-AgNPs have higher standards of infiltration than the GO and silver membrane. The presence of GO-AgNPs provides strong antibacterial activity in the membrane. This study shows the good potential for antibiofouling membrane development for membrane separation.

Manafi et al. [128] observed that the insolvent phase polyacrylamide (PAM) –graphene-based nanocomposites were synthesized to allow better dispersion of graphene nanoplatelets in the matrix. This process was carried out using acid in the case of functionalized graphene nanoplatelets (FGNp) to achieve the fine dispersion found in the PAM matrix. In addition to GO, both the efficiency and supernatant turbidity decreased. There was a concentration change of GO and the water was cleaned efficiently. Moreover, Lompe et al. [129] showed that a composite material can be formed by combining powdered activated carbon (PAC) with the magnetic properties of iron oxide nanoparticles (NPs). The elimination of ammonia did not influence the iron oxide NPs on the PAC in a bioreactor. The PAC showed good performance in terms of both being adsorbent and removing biological growth in drinking water. Kim et al. [130] studied graphene-based nanofiltration membranes, which were used for water purification. By altering the level of arc discharge, the degree of oxidation increased from 28.1% at 1 A to 53.9% at 4 A. Filters made of graphene sheets have excellent ion rejection capabilities compared to polyamide membranes. The high-carbon nanochannels show a tendency towards high water flux and show rejection in the case of hydrophobic interactions.

Yin et al. [131] demonstrated how graphene nanosheets are used in an in situ interfacial polymerization process. GO nanosheets have a multilayer structure. The spacing between layers was 0.83 nm and the GO nanosheets were dispersed in the polyamide, which improved the salt rejection in water. The GO nanosheets also rejected NaCl and Na2SO4 from water. GO sheets serve as water channels. The addition of different nanoparticle in carbon material also attempted to improve magnetic and other desired properties [132]. Pawar et al. [133] showed that the hydrothermal method can be used for the synthesis of MWCNTs and GO, where the nanostructure is based on single-crystal hematite (Fe2O3). The samples were analyzed by performing different tests, such as X-ray diffraction, field emission scanning electron microscopy, and high-resolution electron microscopy tests. This technique involves lower fabrication costs for material formation and is also suitable for photocatalysis, having a high success rate for water purification. Sharma et al. [1] used graphene–carbon nanotube–iron oxide composites formed via the synthesis of carbon and iron-based nanomaterials for water purification. Due to the large surface area of graphene and graphene oxide, the absorption rate of impurities is higher. Magnetic-based nanomaterials are used to remove impurities and the extraction of nanomaterials from treated water is achieved by using external magnets. Tuan et al. [134] showed that capacitive deionization can be used for water purification to reduce the harshness of water by using an electrochemical double layer. There is extensive ongoing research on the use of reduced graphene oxide as a catalyst as compared to all other carbon-based materials. The efficiency of CDI was observed to be 3.54 mg by using purified rGO as an electrode.

5. Conclusions

In the present paper, a comprehensive review was performed of recent developments related to water purification technology using carbon materials. The most relevant patents and papers published in the last decade were carefully selected. In the initial stage, fabrication and structural properties were discussed. Adsorption is a well-established method for water purification. Activated carbon, CNTs, GO, and rGO have been widely tested for adsorptive removal of impurities due to their superior physicochemical properties. The FESEM image of activate carbon displayed macropores on its surface, with an internal surface area of up to 1500 m2/g. Improvements in effectiveness have been achieved by combining carbon nanomaterials with other nanoparticles (activated carbon–Fe3O4 nanoparticle composites) and through structural modifications (vertically aligned CNTs). These are new approaches that can improve the effectiveness and efficiency.

The recent patents over the last decade related to water purification technologies using carbon materials were discussed. Activated carbon is the most widely used carbon material in either original or combined form. The recent research articles on water purification using carbon materials were also covered. The hydrophilic surfaces of CNTs enable backwashing and rinsing. The use of carbon materials in combined form, such as MWCNT-ZrO2, rGO–Ti, and GO-Ag, are recent attempts at improving the effectiveness of water purification. The usage of carbon nanomaterials as nanoelectrodes adds one more reason for their application as water purification materials.

In conclusion, carbon-based materials can be used for small- and large-scale water purification technologies. They are cost-effective and eco-friendly options, which have experienced a steady increase in attention from the research community.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K. and M.G.K.; methodology, A.K.; investigation, A.Y. and T.R.R.; data curation, H.R.; writing—original draft preparation, A.K. and M.G.K.; writing—review and editing, I.E.S.; visualization, A.K.; supervision, I.E.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Virender, K.S.; McDonald, T.J.; Kim, H.; Garg, V.K. Magnetic graphene-carbon nanotube iron nanocomposites as adsorbents and antibacterial agents for water purification. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2015, 225, 229–240. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, M.J.; Tung, V.C.; Kaner, R.B. Honeycomb Carbon: A Review of Graphene. Chem. Rev. 2009, 110, 132–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, S.; Bindal, R.C.; Tewari, P.K. Carbon nanotube membranes for desalination and water purification: Challenges and opportunities. Nano Today 2012, 7, 385–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasrabadi, A.T.; Foroutan, M. Ion-separation and water-purification using single-walled carbon nanotube electrodes. Desalination 2011, 277, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.K.; Filip, J.; Zboril, R.; Varma, R.S. Natural inorganic nanoparticles—Formation, fate, and toxicity in the environment. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 8410–8423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-F.; Truong, Q.D.; Chen, J.-R. Graphene sheets synthesized by ionic-liquid-assisted electrolysis for application in water purification. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2013, 264, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreeprasad, T.; Maliyekkal, S.M.; Lisha, K.; Pradeep, T. Reduced graphene oxide–metal/metal oxide composites: Facile synthesis and application in water purification. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 186, 921–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, P.S.; Ismail, A.F.; Ng, B.C. Carbon nanotubes for desalination: Performance evaluation and current hurdles. Desalination 2013, 308, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.-S.; Zhong, L.-S.; Song, W.-G.; Wan, L.-J. Synthesis of hierarchically structured metal oxides and their application in heavy metal ion removal. Adv. Mater. 2008, 20, 29772008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Yan, X.-P. Preparation, characterization, and application of L.-cysteine functionalized multiwalled carbon nanotubes as a selective sorbent for separation and preconcentration of heavy metals. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2008, 18, 1536–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chengfeng, R.; Rongrong, R. Get Rid of Chlorine Residue Active Carbon Water Purification Filter Core. U.S. Patent CN08791367U, 26 April 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Song, B.; Jian, L.; Honghu, P.; Shunpeng, Z.; Zhonghua, Z.; Jianqi, Z.; Guocheng, Z. Corncob Active Carbon Water Purification Filter Core. U.S. Patent CN204918207U, 2 October 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Du, H. Active Carbon Water Purification Device with Automatic Flushing and Pollutant Discharge Functions. U.S. Patent CN201678532U, 26 March 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jie, L.; Min, L.; Jing, X. Active Carbon Water Purification Unit. U.S. Patent CN207478059U, 12 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Triestam, A. Hot Water Heater Has Water Container with Electrical Heating Body, Replaceable Active Carbon Water Filter(s) and/or UV Radiation Source(s); Water Flows Through Filter and/or Past UV Source. U.S. Patent DE19946064A1, 16 December 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Archer, V.L. Activated Carbon Water Filter. U.S. Patent CN209397001U, 17 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gehrke, I.; Geiser, A.; Somborn-Schulz, A. Innovations in nanotechnology for water treatment. Nanotechnol. Sci. Appl. 2015, 8, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezoti, O.; Cazetta, A.L.; Bedin, K.C.; Souza, L.S.; Martins, A.C.; Silva, T.L.; Júnior, O.O.S.; Visentainer, J.V.; Almeida, V.C. NaOH-activated carbon of high surface area produced from guava seeds as a high-efficiency adsorbent for amoxicillin removal: Kinetic, isotherm and thermodynamic studies. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 288, 778–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dąbrowski, A.; Podkościelny, P.; Hubicki, Z.; Barczak, M. Adsorption of phenolic compounds by activated carbon—A critical review. Chemosphere 2005, 58, 1049–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Dastgheib, S.A.; Karanfil, T. Adsorption of dissolved natural organic matter by modified activated carbons. Water Res. 2005, 39, 2281–2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady-Estévez, A.S.; Kang, S.; Elimelech, M. A Single-Walled-Carbon-Nanotube Filter for Removal of Viral and Bacterial Pathogens. Small 2008, 4, 481–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, Y.; Kim, C.; Seo, D.K.; Kim, T.; Lee, J.S.; Kim, Y.H.; Ahn, K.H.; Bae, S.S.; Lee, S.C.; Lim, J.; et al. High performance and antifouling vertically aligned carbon nanotube membrane for water purification. J. Membr. Sci. 2014, 460, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Yang, L. Dual functional nisin-multi-walled carbon nanotubes coated filters for bacterial capture and inactivation. J. Biol. Eng. 2015, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ain, Q.-U.-; Farooq, M.U.; Jalees, M.I. Application of magnetic graphene oxide for water purification: Heavy metals removal and disinfection. J. Water Process. Eng. 2019, 33, 101044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lujanienė, G.; Šemčuk, S.; Lečinskytė, A.; Kulakauskaitė, I.; Mažeika, K.; Valiulis, D.; Pakštas, V.; Skapas, M.; Tumėnas, S. Magnetic graphene oxide based nano-composites for removal of radionuclides and metals from contaminated solutions. J. Environ. Radioact. 2016, 166, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, B. Adsorption and coadsorption of organic pollutants and a heavy metal by graphene oxide and reduced graphene materials. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 281, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yan, L.; Xu, W.; Guo, X.; Cui, L.; Gao, L.; Wei, Q.; Du, B. Adsorption of Pb(II) and Hg(II) from aqueous solution using magnetic CoFe2O4-reduced graphene oxide. J. Mol. Liq. 2013, 191, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, M.H.; Phan, N.H.; Nguyen, T.K.P.; Pham, T.T.S.; Nguyen, V.K.; Vu, T.T.T. Activated carbon/Fe3O4 nanoparticle composite: Fabrication, methyl orange removal and regeneration by hydrogen peroxide. Chemosphere 2011, 85, 1269–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusain, R.; Kumar, N.; Ray, S.S. Recent advances in carbon nanomaterial-based adsorbents for water purification. Co-ord. Chem. Rev. 2020, 405, 213111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimiev, A.M.; Alemany, L.B.; Tour, J.M. Graphene oxide. Origin of acidity, its instability in water, and a new dynamic structural model. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 576–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L. Structure and synthesis of graphene oxide. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2019, 27, 2251–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Yang, J.; Li, X.; Li, W.; Zhang, X.; Koratkar, N.; Yu, Z. Flame synthesis of superhydrophilic carbon nanotubes/ni foam decorated with fe2onanoparticles for water purification via solar steam generation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 13229–13238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Liang, S.; Wu, Y.; Yang, M.; Huang, X. Cross-stacked super-aligned carbon nanotube/activated carbon composite electrodes for efficient water purification via capacitive deionization enhanced ultrafiltration. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2020, 14, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libing, Q.; Yabei, T.; Yanqing, X.; Ning, L. Modified Basalt Fibre Applied to Water Quality Purification. CN107262042A, 20 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, C.; Ma, T.; Wang, J.; Zhou, Y. Removal of heavy metals from aqueous solution using carbon-based adsorbents: A review. J. Water Process. Eng. 2020, 37, 101339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Saleem, H.; Ibrar, I.; Naji, O.; Hawari, A.A.; AlAnezi, A.A.; Zaidi, S.J.; Altaee, A.; Zhou, J. Recent developments in forward osmosis membranes using carbon-based nanomaterials. Desalination 2020, 482, 114375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweetman, M.J.; May, S.; Mebberson, N.; Pendleton, P.; Vasilev, K.; Plush, A.S.E.; Hayball, J.D. Activated carbon, carbon nanotubes and graphene: Materials and composites for advanced water purification. J. Carbon Res. 2017, 3, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, M. Mechanical properties of activated carbon fibers. In Activated Carbon Fiber and Textiles; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2017; pp. 167–180. [Google Scholar]

- Dresselhaus, M.S.; Lin, Y.; Rabin, O.; Jorio, A.; Filho, A.S.; Pimenta, M.; Saito, R.; Samsonidze, G.; Dresselhaus, G. Nanowires and nanotubes. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2003, 23, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, C.H.; Baek, Y.; Lee, C.; Kim, S.O.; Kim, S.; Lee, S.; Kim, S.-H.; Bae, S.S.; Park, J.; Yoon, J. Carbon nanotube-based membranes: Fabrication and application to desalination. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2012, 18, 1551–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinds, B.J.; Chopra, N.; Rantell, T.; Andrews, R.; Gavalas, V.; Bachas, L.G. Aligned Multiwalled Carbon Nanotube Membranes. Science 2004, 303, 62–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.C.; Shin, Y.M.; Lee, Y.H.; Lee, B.S.; Park, G.-S.; Choi, W.B.; Lee, N.S.; Kim, J.M. Controlling the diameter, growth rate, and density of vertically aligned carbon nanotubes synthesized by microwave plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2000, 76, 2367–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, J.K.; Noy, A.; Huser, T.; Eaglesham, A.D.; Bakajin, O. Fabrication of a carbon nanotube-embedded silicon nitride membrane for studies of nanometer-scale mass transport. Nano Lett. 2004, 4, 2245–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, U.; Holst, R. Über die säurenatur und die methylierung von graphitoxyd. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 2006, 72, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruess, G. Über das graphitoxyhydroxyd (graphitoxyd). Chem. Mon. 1947, 76, 381–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummers, W.S., Jr.; Offeman, R.E. Preparation of graphitic oxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1958, 80, 1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Chen, Z.; Du, X.; Logan, M.J.; Sippel, J.; Nikolou, M.; Kamaras, K.; Reynolds, J.R.; Tanner, D.; Hebard, A.F.; et al. Transparent, conductive carbon nanotube films. Science 2004, 305, 1273–62004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, H.; Zhang, X. Facile fabrication of freestanding ultrathin reduced graphene oxide membranes for water purification. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qianfeng, L. Graphene Water Purifier. U.S. Patent CN109502896A, 22 March 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Longjingling, H.; Information Tech Co. Ltd. A Kind of Multiple-Effect Water Treatment Agent and Preparation Method thereof and Method for Treating Water. U.S. Patent CN107265530A, 20 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Liangti, Q.; Cheng, H.; Zhang, P.P. Graphene Solar Energy Water Cleaning Foam as Well as Preparation Method and Application. U.S. Patent CN108002366A, 8 May 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hostetter, W.E. Carbon Water Filter. U.S. Patent US3612279A, 12 October 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Tarifi, M.H. PCO/UVC/Carbon Water Filter. U.S. Patent US2014166591A1, 19 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, A.; Brigano, J.; Schroeder, H.; Popovic, V. Activated Carbon Water Filter with Reduced Leachable Arsenic and Method for Making the Same. U.S. Patent WO2010144175A1, 16 December 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T. Active Carbon Water Treatment Agent. U.S. Patent CN107555518A, 9 January 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Z.; Li, M. Aqua Pure Extract System and Method Are Used in Health Preserving Wine Production. U.S. Patent CN106830474A, 13 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, W.; Jiang, Y.; Lin, X.; Wang, L.; Guo, S.; Shen, J.; Peng, P.; Wang, D. A Kind of Rural Area Sub-Prime of Energy-Saving and Emission-Reduction is for Water Purification Integral System. U.S. Patent CN109081477A, 25 December 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Iang, Y. Energy-Saving and Water-Saving Type Water Purifier. U.S. Patent CN103043836A, 17 April 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, P.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, K.; Chen, T. A Kind of Active Carbon Filter Core that Household Water Filter is Conveniently Replaceable. U.S. Patent CN209361991U, 10 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, X. Possesses the Activated Carbon Filter of Stirring Mixed Function. U.S. Patent CN107298506A, 27 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, L. A Kind of Preparation Method of Sintering Activity Charcoal Water Purification Catridge. U.S. Patent CN109250781A, 22 January 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, Y. Silver Loaded Activated Carbon Water Purification Filter Element. U.S. Patent CN203002379U, 19 June 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.; Liu, Y. Ozone-Biological Activated Carbon Water Purification Method and Device. U.S. Patent CN102126809B, 30 May 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y. Negative-Ion Sintered Activated Carbon Water Purification Filter Element and Preparation Method Thereof. U.S. Patent CN105481045A, 13 April 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C. Active Carbon Water Purification Device is Used in a Kind of Production of Drinking Mineral Water. U.S. Patent CN209537118U, 25 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L. Activated Carbon Water Purification Device and Preparation Method. U.S. Patent CN103055808A, 24 April 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.-H. Large-Capacity Water Treatment Apparatus Having Improved Activated Carbon Water-Purification and Regeneration Function. U.S. Patent WO2016190525A1, 1 December 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gappa, G.; Juentgen, H.; Klein, J.; Reichenberger, J. Activated-Carbon Water Purification Controlled by Analysis of Carbon Content in Water. U.S. Patent CA1048940A, 20 February 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Shifeng, B.H.; Nuannuan, J.; Liang, M.; Mingjuan, S.; Yuanyuan, W. Method for Preparing Graphene Oxide Water Purifying Filter Core. U.S. Patent CN103785223A, 14 May 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, J.; Liang, S. Self-Cleaning Active Carbon Filter Cartridge Device. U.S. Patent CN203803176U, 3 September 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J. Activated-Carbon Filter Cored Structure Water Purification Machine. U.S. Patent CN204058096U, 31 December 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. A Kind of Household Active Charcoal Filter Core. U.S. Patent CN204342473U, 20 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Y. Front Activated Carbon Filter Cartridge-Free Drinking Fountain. U.S. Patent CN101935114A, 5 January 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Qiu, J. Making Method of Negative Ion-Sintered Active Carbon Water Purification Filter Core. U.S. Patent CN103588257A, 19 February 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hyu, I. Carbon Nanoparticle for Photocatalyst. KR101495124B1, 24 February 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Magnusson, J.H. Iodine Resin/Carbon Water Purification System. U.S. Patent CA2052200A1, 28 March 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Claus, F.; Hailong, D.; Ana, K.; Dorothee, G. Carbon Dots (c Dots) Method for Their Preparation and Their Use. EP2913300A1, 2 September 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Qiu, M.; Zhang, J. Water Purification Composite Material and Preparation Method and Application Thereof. U.S. Patent CN107352627A, 17 November 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nobuyuki, S.; Hideo, U. Holder for Activated-Carbon Filter Cartridge. U.S. Patent JPS6295499A, 1 May 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Magnusson, J.; Magnusson, K.J. System Made of Iodine-Containing Resin and Carbon for Water Purification. U.S. Patent DE69103366T, 16 December 1990. [Google Scholar]

- ELS Business Group International LLC. Carbon Water Filter. U.S. Patent TH53392B, 7 October 2002.

- CHE, C. Preparation Method of Graphene Water Purifier Filter Core. U.S. Patent CN108190994A, 22 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Xiuan, A. Ecological Agriculture Co LTD. Compound for Purifying Water. U.S. Patent CN107720976A, 22 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.-L. An Improved Reverse Osmosis/Activated Carbon Water Filter with Automatic Forced Self-Cleaning Function. U.S. Patent TW311477U, 21 June 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Li, N.; Qian, L.; Tan, Y.; Xu, Y. A Kind of Treated Basalt Fiber Applied to Purification of Water Quality. U.S. Patent CN107262042A, 20 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. Dynamic-Static Combined Multistage Filter Bed Cyclone Magnetization Water Purifier. U.S. Patent CN104058542A, 24 September 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G. Rotational Flow Magnetizing Water Purifier with Dynamic and Static Combination Multistage Filter Bed. U.S. Patent CN203269713U, 6 November 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, J. Water Saving Water Purifier. U.S. Patent CN201962142U, 7 September 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, J. A Kind of Novel High Efficiency Water Purifier Equipment for Modern Plant. U.S. Patent CN204619525U, 9 September 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, X. The Activated Carbon Filter of Multi-Filtering. U.S. Patent CN107311378A, 3 November 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Wu, X. A Kind of Low Waste Water Purifier of Energy-Conserving and Environment-Protective. U.S. Patent CN207016571U, 16 February 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, S.; He, L.; Peng, H.; Sun, P.; Xie, M. A Kind of Composition Type Clear Water Machine. U.S. Patent CN203938535U, 12 November 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Yabing, S.; Dong, H.; Shunbin, L.; Lin, B.; Yan, Z.; Sujie, L.; Zehua, Z.; Shaopeng, R. Multi-Functional Water Purifier Integrated with Activated Carbon and Low-Temperature Plasma. U.S. Patent CN103145284B, 5 November 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, C. A Kind of Novel Anti-Freezing Water Purifier. U.S. Patent CN207108646U, 16 March 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, S. A Kind of Tap Water Purifier with Active Carbon Backwash Function. U.S. Patent CN109850977A, 7 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.; Huang, L.; Huang, R. A Kind of RO Water Purifier. U.S. Patent CN208747829U, 16 April 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, L. A Kind of Energy-Saving Water Purifier with Multistage Filtering Function. U.S. Patent CN107473475A, 15 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.G. A Domestic Water Purifier Equipped Outdoor. U.S. Patent KR20030070267A, 30 August 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X. Ultrafiltration Water Purification Machine with Water Intake Pressure Adjustment and Display Functions. U.S. Patent CN203728654U, 23 July 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W. A Kind of Novel Intelligent Water Purifier for Family’s Water Purification. U.S. Patent CN204644006U, 16 September 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, X. Rear-Mounted Water Purifier of Four–Core. U.S. Patent CN205346992U, 29 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, W. Water-Saving Water Purifier. U.S. Patent CN105800813A, 27 July 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J. Pressure Charged Heating Water Purifier. U.S. Patent CN204111513U, 21 January 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Z. A Outdoor Water Purifier for Water Treatment. U.S. Patent CN205473053U, 17 August 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, L. High-Precision Ultrafiltration Water Purifier and Water Purification Method Thereof. U.S. Patent CN103979695A, 13 August 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C. Wastewater-Free Water Purifier. U.S. Patent CN107867764A, 3 April 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Z. The Outdoor Water Purifier of Ceramic Element. U.S. Patent CN204454785U, 8 July 2015. [Google Scholar]

- He, D. Ultra-Low-Pressure Reverse Osmosis Water Purifier. U.S. Patent CN206368080U, 1 August 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hui, D.; Yong, W.; Yongshu, Z. A Kind of Wall-Hanging Water Purifier that RO Membrane Cartridge Is Set. U.S. Patent CN204224339U, 25 March 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bin, Y. A Kind of Filter Element of Water Purifier Convenient for Recycling Waste Water. U.S. Patent CN207891156U, 21 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Dong, C.; Lu, Q.; Si, D.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, Y. Water Purifier without Wastewater Discharge. U.S. Patent CN105384274A, 9 March 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Haitao, Y. Electrostatic Activated Carbon Filter Element of Water Purifier. U.S. Patent CN108217804A, 29 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Qiang, Y. Hydroelectric Separation Water Purifier. U.S. Patent CN208843834U, 10 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Xiaofei, L. Water Purifier. CN202415284U, 5 September 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y. RO (Reverse Osmosis) Water Purifier of Pressure-Free Barrel. U.S. Patent CN202808504U, 20 March 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Wang, P. A Kind of Novel Water Purifier. U.S. Patent CN204550255U, 12 August 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, W. Constant-Pressure Water Purifier Using Water Purifying Agent. U.S. Patent CN104671528A, 3 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, R. Vertical Water Purifier. U.S. Patent CN207192981U, 6 April 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ntim, S.A.; Mitra, S. Adsorption of arsenic on multiwall carbon nanotube-zirconia nanohybrid for potential drinking water purification. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2012, 375, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beobide, A.S.; Anastasopoulos, J.; Voyiatzis, G.A.; Lainioti, G.C.; Kallitsis, J.; Kouravelou, K. Embedment of functionalized carbon nanotubes into water purification membrance. Procedia Eng. 2012, 44, 1918–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bakajin, O.; Noy, A.; Fornasiero, F.; Grigoropoulos, C.P.; Holt, J.K.; Bin Kim, S.; Park, H.G. Nanofluidic carbon nanotube membranes: Applications for water purification and desalination. In Nanotechnology Applications for Clean Water, 2nd ed.; Elsevier Inc.: Oxford, UK; Waltham, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, R.; Ali, E.; Bee, S.; Hamid, A.; Ramakrishna, S.; Zaman, Z. Carbon nanotube membranes for water puri fi cation: A bright future in water desalination. DES 2014, 336, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masinga, S.P.; Nxumalo, E.N.; Mamba, B.B.; Mhlanga, S.D. Microwave-induced synthesis of b-cyclodextrin/N-doped carbon nanotube polyurethane nanocomposites for water purification. J. Phys. Chem. Ear 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Lu, Z.; Jin, S.; Zheng, Y.; Ye, T.; Yang, D.; Li, Y.; Zhu, L.; Zhu, L. TiO2 nanotube-carbon macroscopic monoliths with multimodal porosity as efficient recyclable photocatalytic adsorbents for water purification. Math. Chem. Phys. 2016, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-phan, T.; Hung, V.; Jung, E.; Oh, E.; Hyun, S.; Suk, J.; Lee, B.; Woo, E. Applied surface science reduced graphene oxide–titanate hybrids: Morphologic evolution by alkali-solvothermal treatment and applications in water purification. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2012, 258, 4551–4557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, F.; Luo, T.; Qiu, L.; Yuan, Y. An easy method to synthesize graphene oxide–FeOOH composites and their potential application in water purification. Mater. Res. Bull. 2013, 48, 2180–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Qin, J.; Xia, P.; Guo, B.; Yang, C.; Sun, X.; Qin, J.; Xia, P.; Guo, B.; Yang, C.; et al. Graphene oxide-silver nanoparticle membrane for biofouling control and water purification. Chem. Eng. J. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manafi, M.; Manafi, P.; Agarwal, S.; Bharti, A.K.; Asif, M.; Gupta, V.K. Synthesis of Nanocomposites from Polyacrylamide and Graphene Oxide: Application as flocculants for water purification. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lompe, K.M.; Menard, D.; Barbeau, B. Performance of biological magnetic powdered activated carbon for drinking water purification. Water Res. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Song, Y.; Ibsen, S.; Ko, S.; Heller, M.J. Controlled degrees of oxidation of nanoporous graphene filters for water purification using an aqueous arc discharge. Carbon 2016, 109, 624–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Zhu, G.; Deng, B. Graphene oxide (GO) enhanced polyamide (PA) thin-film nanocomposite (TFN) membrane for water purification. Desalination 2015, 379, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gondal, M.A.; Ilyas, A.M.; Baig, U. Facile synthesis of silicon carbide-titanium dioxide semiconducting nanocomposite using pulsed laser ablation technique and its performance in photovoltaic dye sensitized solar cell and photocatalytic water purification. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawar, R.C.; Choi, D.; Lee, C.S. Reduced graphene oxide composites with MWCNTs and single crystalline hematite nanorhombohedra for applications in water purification. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, T.N.; Chung, S.; Lee, J.K.; Lee, J. Improvement of water softening efficiency in capacitive deionization by ultra purification process of reduced graphene oxide. Curr. Appl. Phys. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pudza, M.Y.; Abidin, Z.Z.; Rashid, S.A.; Yasin, F.M.; Noor, A.S.M.; Issa, M.I. Eco-Friendly Sustainable Fluorescent Carbon Dots for the Adsorption of Heavy Metal Ions in Aqueous Environment. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Cui, A.; Xu, Y.; Fu, X. Graphene oxide–TiO2 composite filtration membranes and their potential application for water purification. Carbon 2013, 62, 465–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegab, H.M.; Zou, L. Graphene oxide-assisted membranes: Fabrication and potential applications. J. Membr. Sci. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamage, S.M.; Sathasivan, A. Chemosphere A review: Potential and challenges of biologically activated carbon to remove natural organic matter in drinking water puri fi cation process. Chemosphere 2017, 167, 120–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghu, M.S.; Kumar, K.Y.; Prashanth, M.K.; Prasanna, B.P.; Vinuth, R.; Kumar, C.B.P. Adsorption and antimicrobial studies of chemically bonded magnetic graphene oxide-Fe3O4 nanocomposite for water purification. J. Water Process Eng. 2017, 17, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzuto, C.; Pugliese, G.; Bahattab, M.A.; Aljlil, S.A.; Drioli, E.; Tocci, E. Multiwalled carbon nanotube membranes for water purification. separation and purification technology. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarasidis, C.V.; Plakas, V.K.; Karabela, J.A. Novel water-purification hybrid processes involving in-situ regenerated activated carbon, membrane separation and advanced oxidation. Chem. Eng. J. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, A.; Ponnan, E.; Jagadeesh, B.B. TiO2 nanosheet-graphene oxide based photocatalytic hierarchical membrane for water purification. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2017, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maji, S.; Ghosh, A.; Gupta, K.; Ghosh, A.; Ghorai, U.; Santra, A.; Sasikumar, P.; Ghosh, U.C. Efficiency evaluation of arsenic(III) adsorption of novel graphene oxide@iron-aluminium oxide composite for the contaminated water purification. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathore, P.; Kotia, A. Gravity water purifier using activated carbon form coconut shell for rural application. Plant Arch. 2020, 20, 2626–2640. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).