Abstract

The time relaxation model has proven to be effective in regularization of Navier–Stokes Equations. This article reviews several published works discussing the development and implementations of time relaxation and time relaxation models (TRMs), and how such techniques are used to improve the accuracy and stability of fluid flow problems with higher Reynolds numbers. Several analyses and computational settings of TRMs are surveyed, along with parameter sensitivity studies and hybrid implementations of time relaxation operators with different regularization techniques.

1. Introduction

Time relaxation models (TRM) are a novel class of regularizations of the Navier–Stokes Equations (NSE) formulated by nudging solutions of the NSE toward a spatially-regularized solution. This is accomplished by adding a relaxation term to the momentum equations of the NSE, i.e.,

where is fluid velocity, p is pressure, is kinematic viscosity, and accounts for external forcing. The scaling parameter has the units . For our purposes, the relaxation term is constructed to exclusively dissipate (through time) scales of motion beneath a user-selected threshold.

In a general sense, the notion of nudging was first seen in [1,2], though instead of dissipating small velocity scales, the authors nudged computed velocity solutions toward recorded atmospheric data. If we momentarily let , where is appropriately-interpolated real-world data while is sufficiently smooth, the simplified ODE,

shows that for some constant C,

Over an extended time scale it becomes apparent that in this context, computed solutions to a model like (1) move toward . The rate and extent that this occurs is wholly determined by the problem settings, , and the relaxation parameter .

It is well understood that the principal difficulty in accurately resolving turbulent fluid flow is one of scale. In viscous, incompressible flow in three dimensions, K-41 theory suggests that, given a Reynolds number , a direct numerical simulation of the NSE requires spatial discretization resulting in degrees of freedom [3]. Such calculations can become challenging, and often unfeasible for practical problems at even modest Reynolds numbers. While some practitioners might be tempted to side-step the difficulty by simply using a coarse discretization, under-resolving the dissipation scale of motion can lead to unacceptable error. As a result, several techniques have been developed to relax these difficult discretization requirements.

The TRMs discussed in this paper were devised to address this difficulty by nudging a carefully under-resolved numerical approximation to the NSE toward a spatially filtered solution. This is a practical solution since the larger, dominant scales of motion contain the bulk of a flow’s kinetic energy, and account for most of the momentum transport. Hence, it becomes possible to accurately resolve the largest scales of motion without the burden of resolving the smallest.

Broadly speaking, regularization terms in time relaxation models are often formulated:

where G is a smoothing kernel selected to act as a low-pass spatial filter for the fluid velocity. Hence, including such a term in (1) acts to nudge computed solutions toward the spatially-filtered velocity. The rate and scale at which this occurs is determined by , and the filtering process

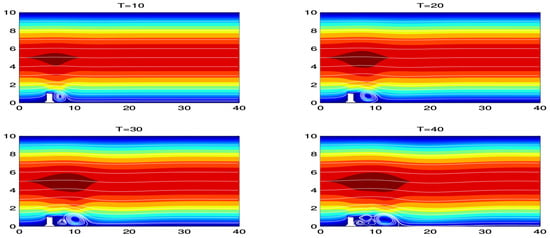

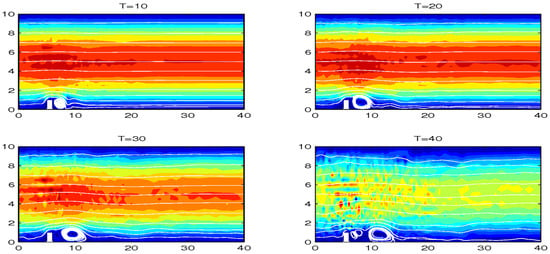

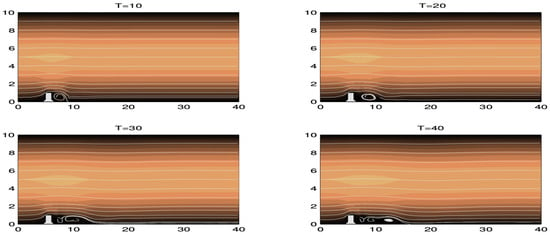

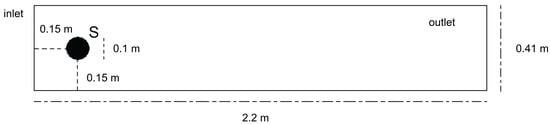

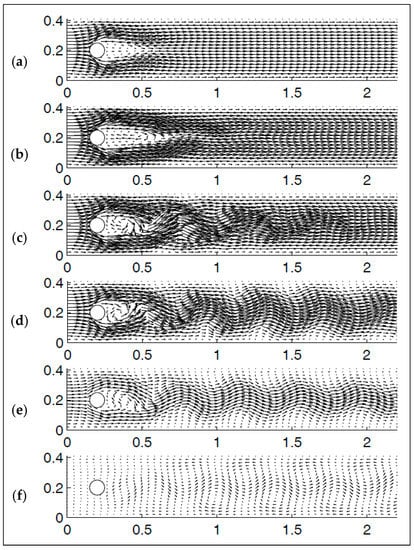

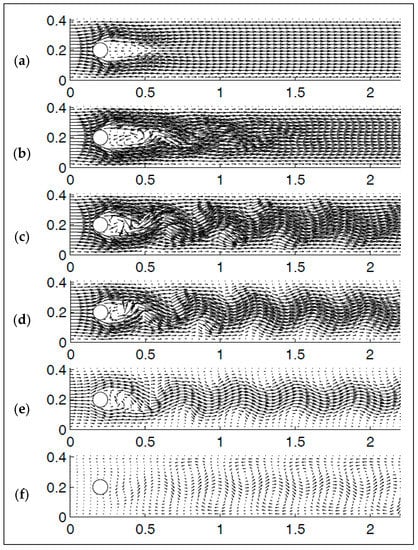

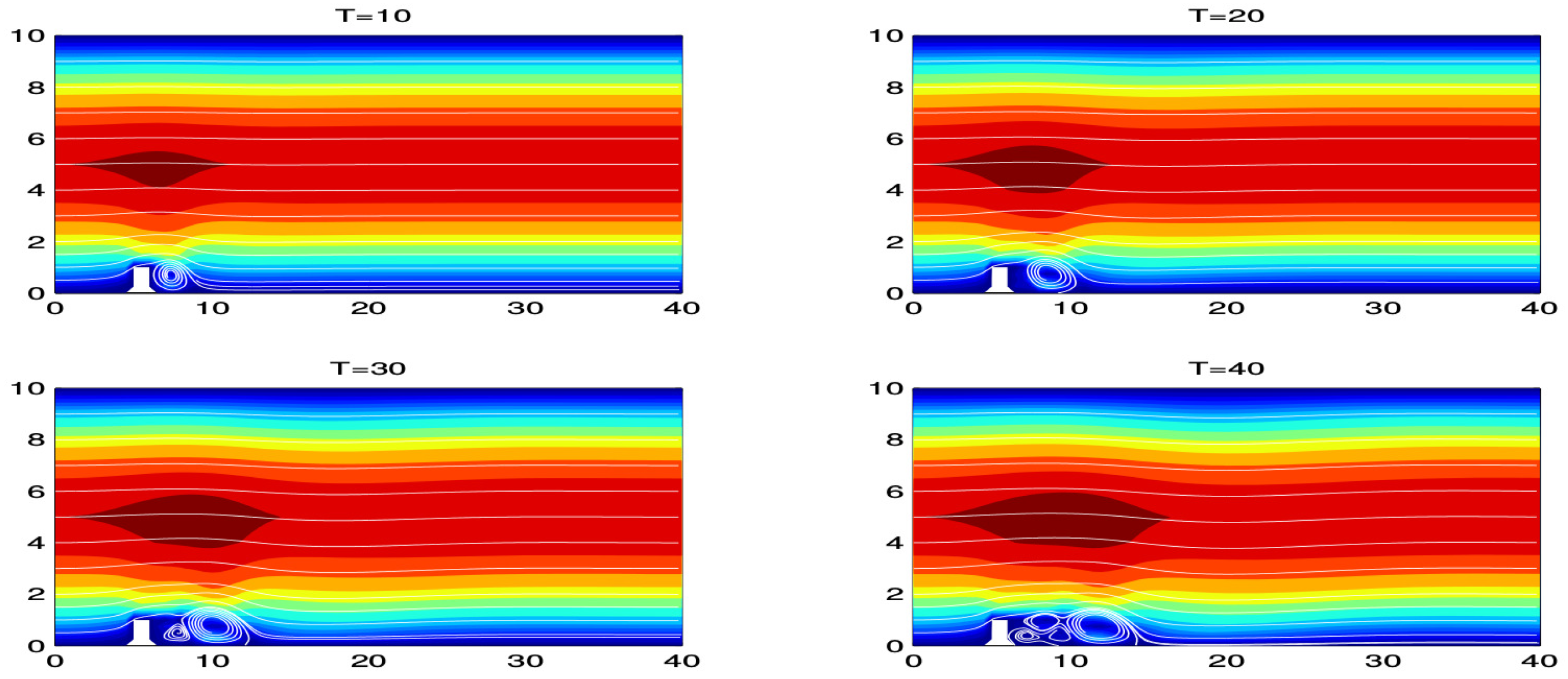

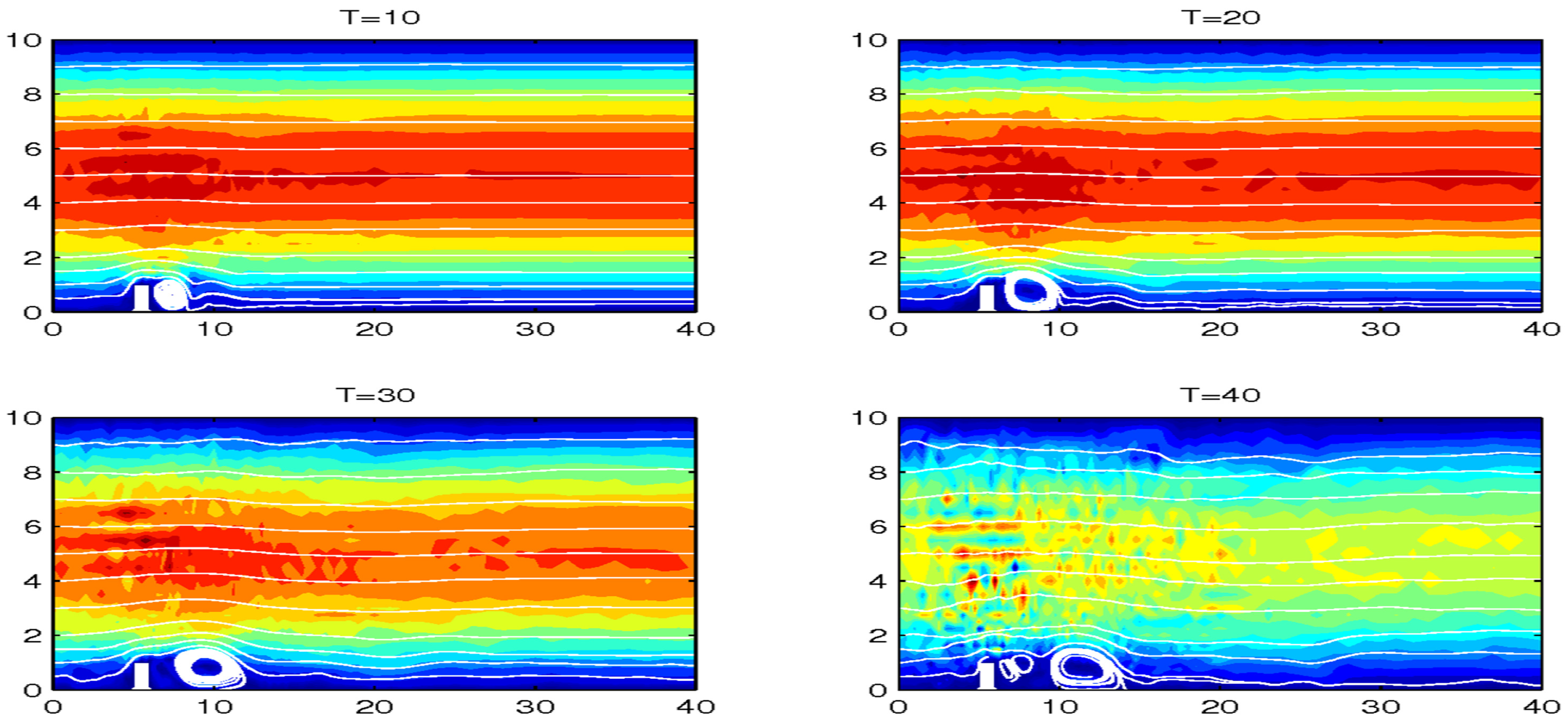

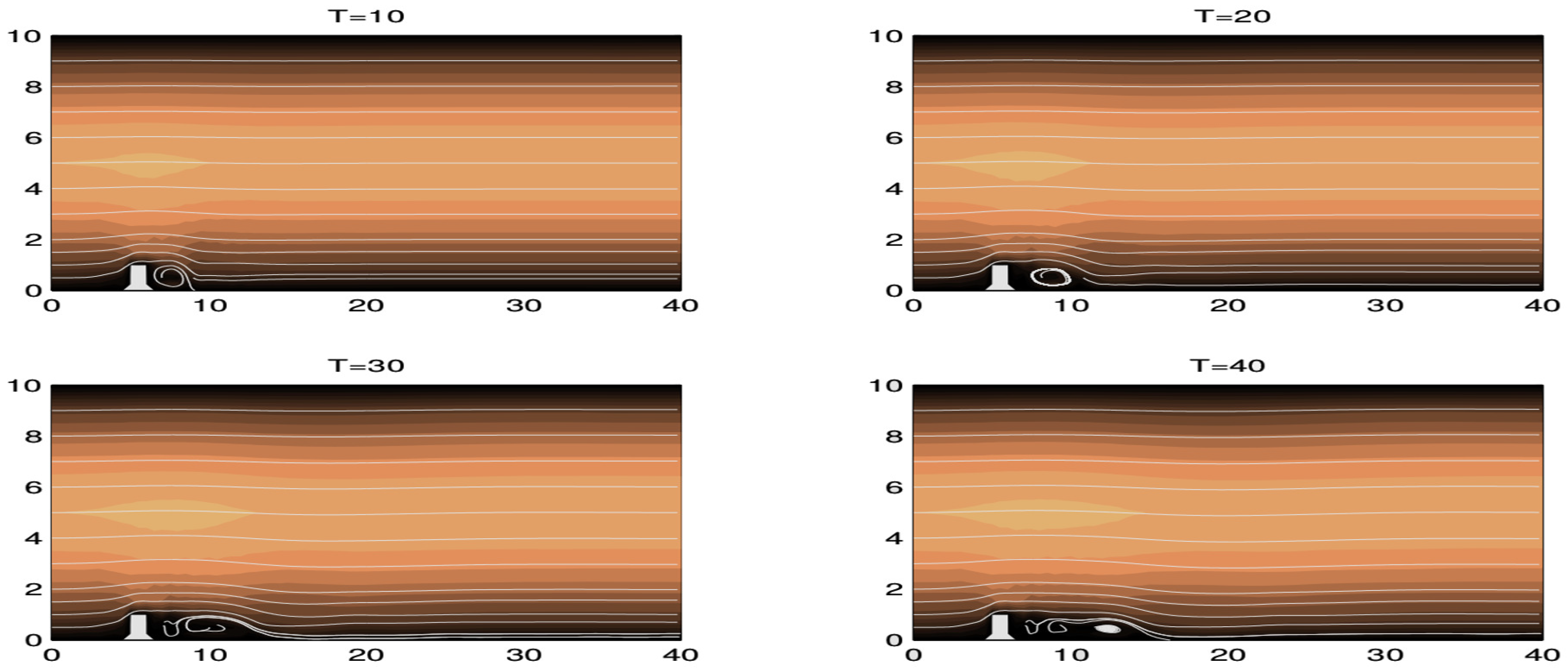

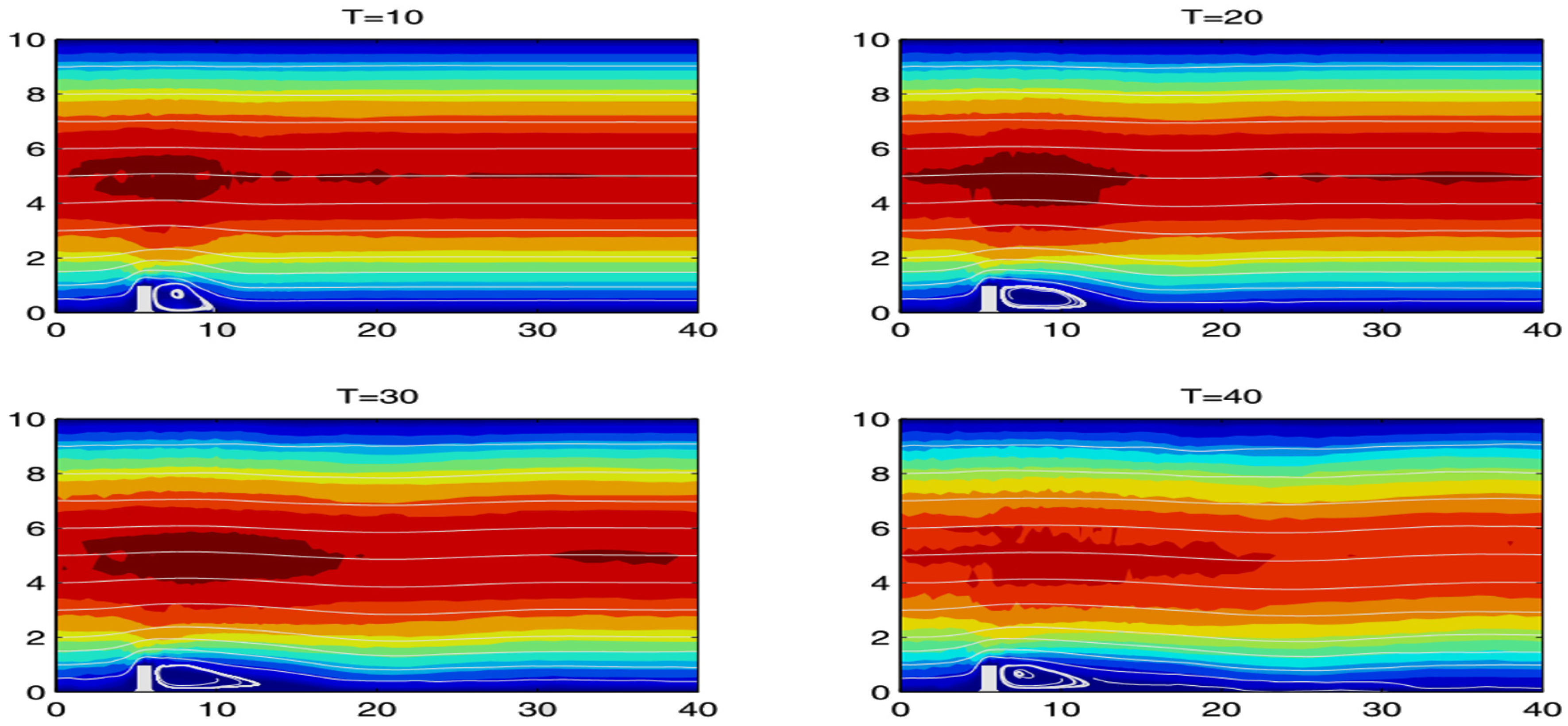

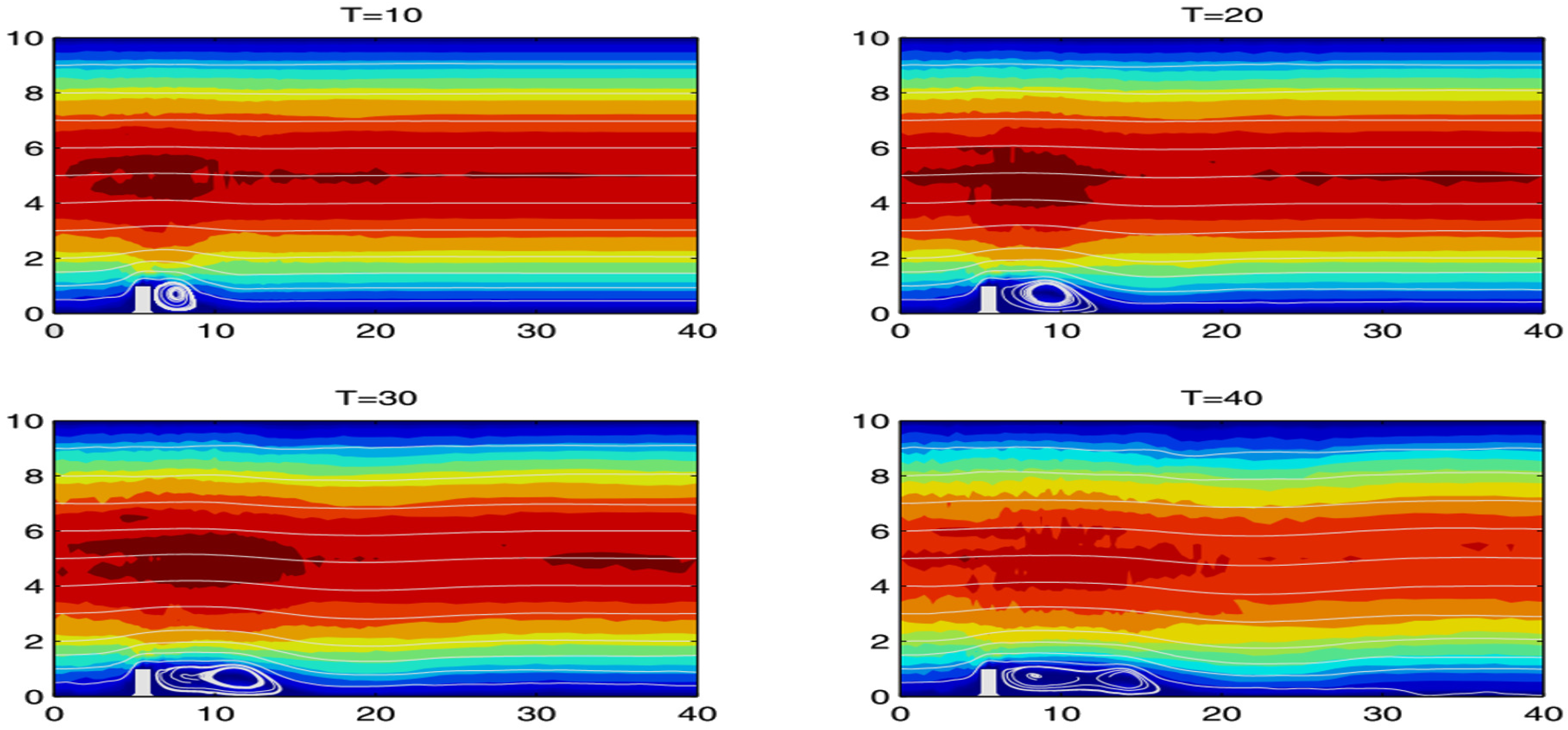

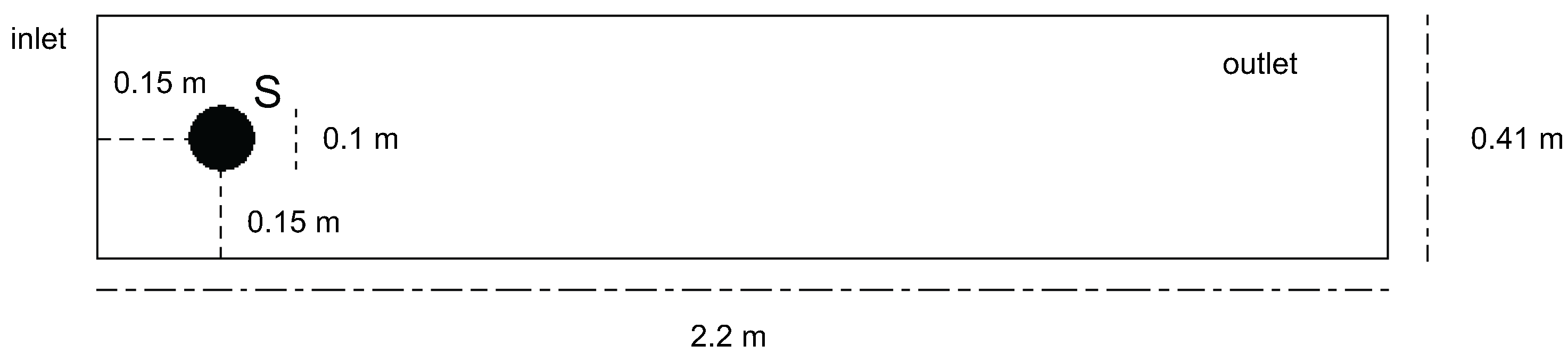

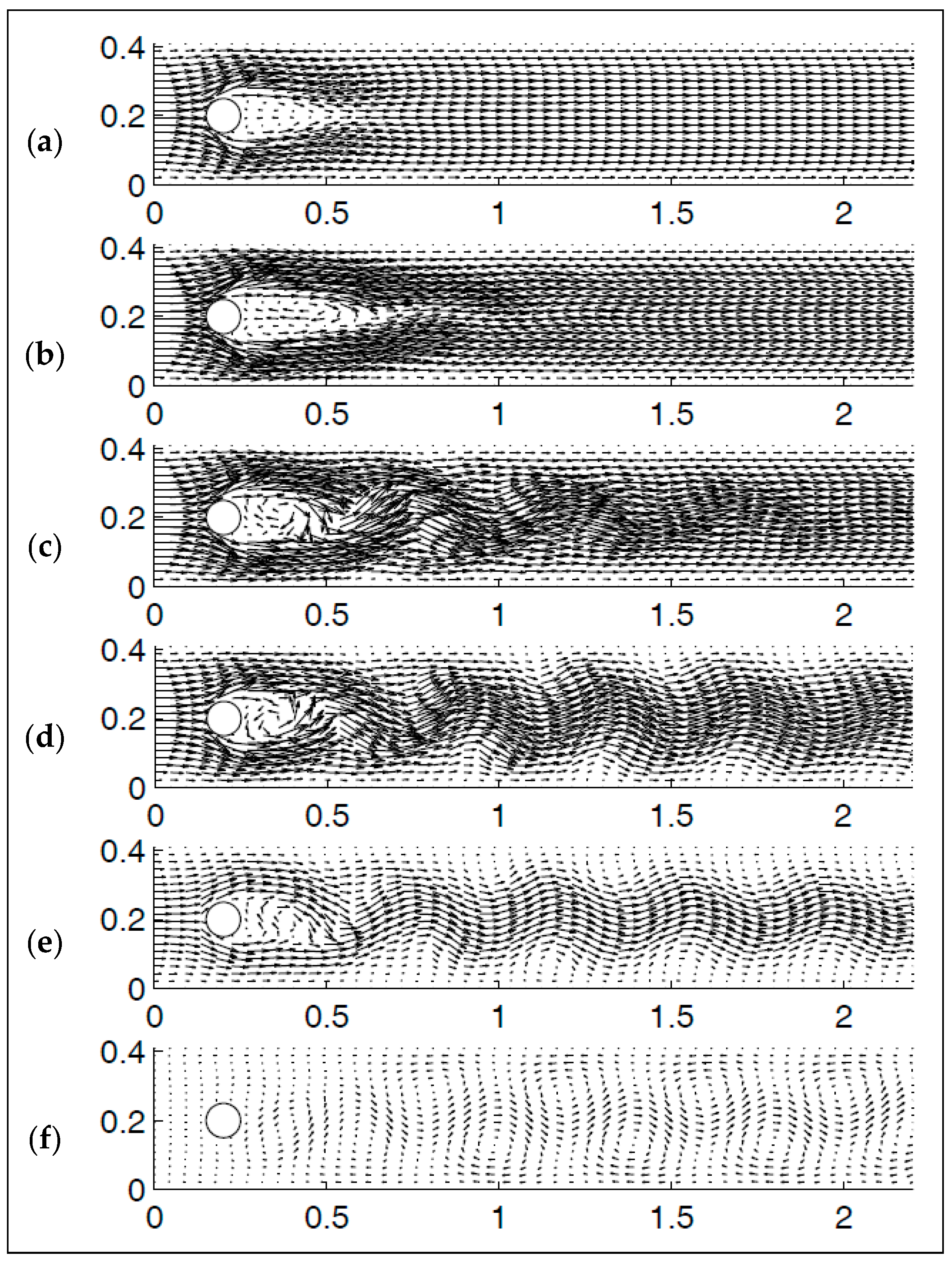

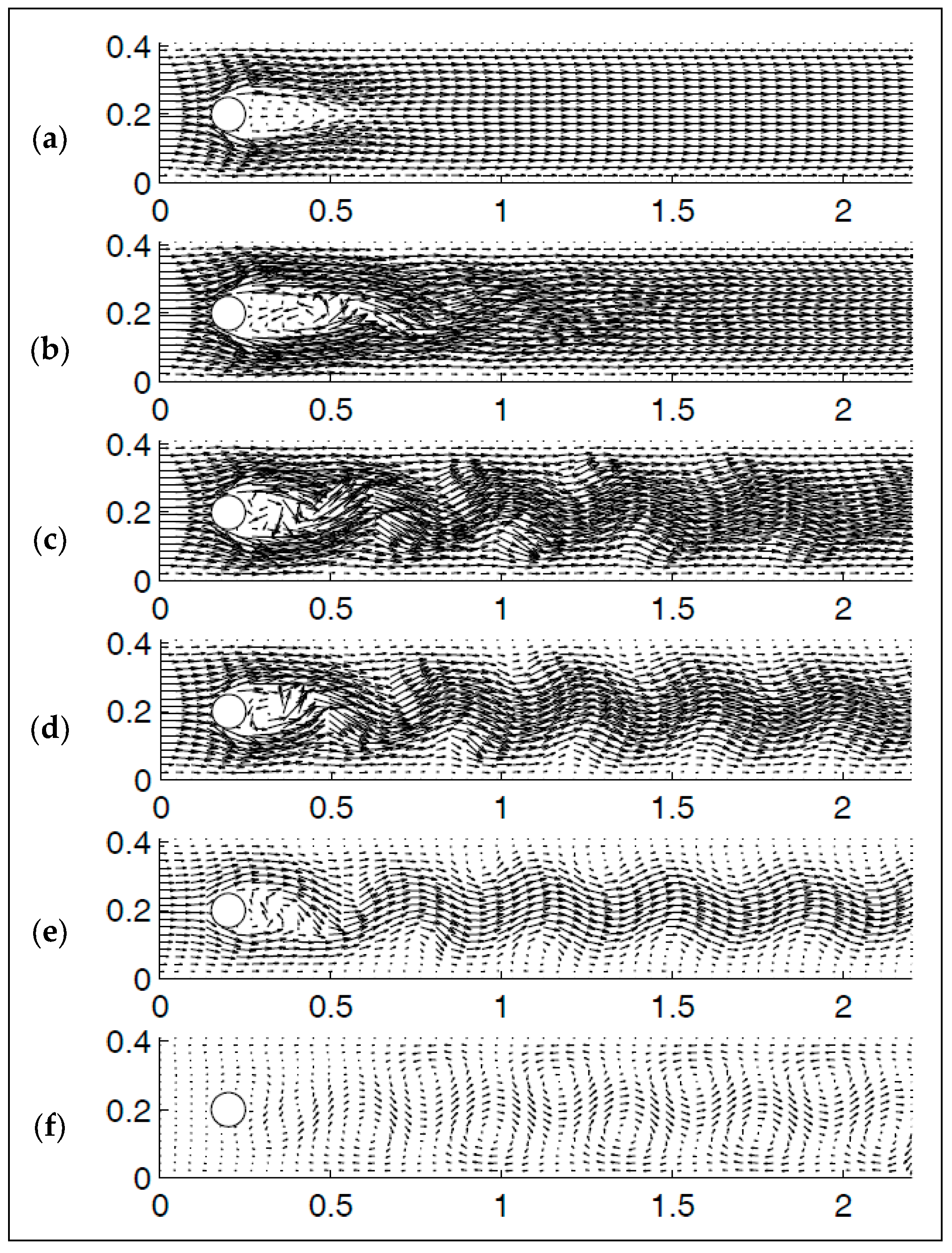

The goal of this article is to effectively summarize the body of research pertaining to TRM models, and the results of their implementations in computational settings. We begin in Section 2 where we briefly introduce basic notational and function spaces, as well as the differential filtering used in TRMs and the higher-order approximate deconvolution operators. We then introduce the time relaxation techniques seen in [4,5,6] in Section 3. We present and briefly discuss linear and nonlinear forms of time relaxation terms, and their effects on the transfer of kinetic energy from large scales of motion to small. This discussion continues in Section 4 where a brief survey of implementations utilizing finite element methods (FEM) is included, [7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. We will continue surveying these results by comparing the performance of the several TRM formulations and FEM techniques on the benchmark flow past a full step problem. Section 5 presents a summary of a sensitivity analysis seen in [13]. We conclude in Section 6 with a brief summary, and a discussion of open problems.

2. Notation and Preliminaries

Throughout this article and the papers referenced, the common function spaces and norms considered are,

where Q contains all pressure functions of finite energy , and contains all fluid velocities with finite kinetic energy , and finite rate of energy dissipation . The space is required given the added restriction on incompressible flows that be divergence-free.

It is often necessary in convergence analyses to impose significant smoothness assumptions on the true, weak solutions to the incompressible NSE. Typically, we require these solutions to be bounded, and to weakly admit several spatial derivatives. For instance, the sufficient condition of Lemma 1 requires the true solution to be in time, and in space where,

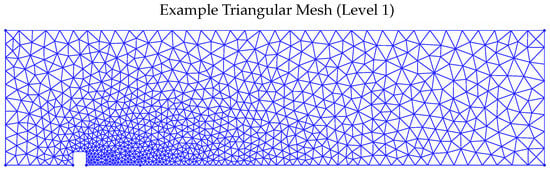

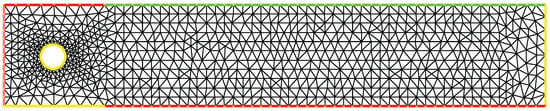

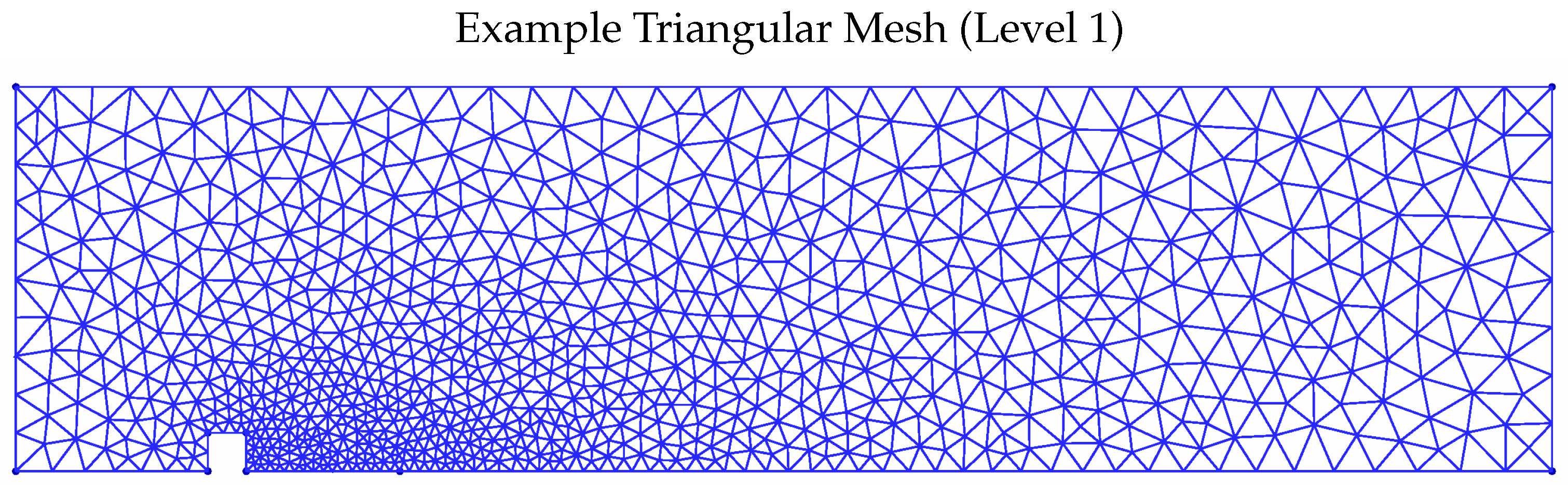

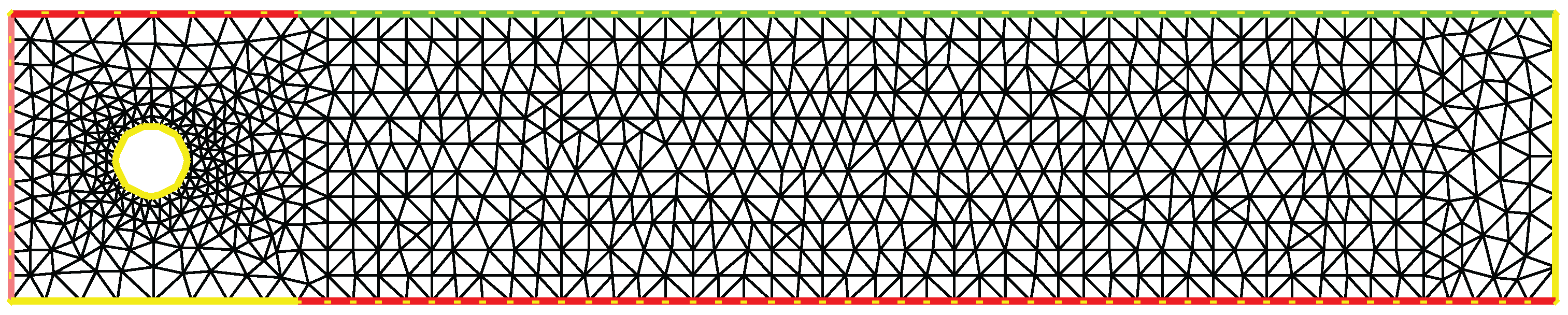

When discussing computations, h represents a minimal mesh scale, and , , and represent the discrete counterparts to and , respectively. There have been a variety of spatial discretizations of TRMs, and in an effort to simplify the notation in this article we carry this notation between these discussions.

2.1. Differential Filtering

The notion of a differential smoothing filter was introduced by Germano [14].

Definition 1 (Continuous Differential Filter).

Given and a given filtering radius of 0, we define the filtering of ϕ as , where is the solution to the PDE.

We can infer from Definition 1 that on a suitable domain , given a particular quantity , the low-pass filtered quantity is the unique solution to the equation where .

The spatial filtering process behaves as local averaging. In [14], it is shown that in 3D, the Green’s function for the PDE defined above is a smoothing kernel. This differs from other averaging techniques like long-time averaging, as features present beneath the spatial filter length scale will certainly be removed. In contrast, in long-time averaging persistent flow, features will remain if they are steady in time, regardless of spatial scale.

It is clear that repeated applications of the differential spatial filter will result in added truncation of sub filter-length scales. This is important in approximate deconvolution techniques, which are discussed in the following section. For notational simplicity, as it becomes necessary to filter quantities multiple times, let the number of over-bars account for this information such that if is filtered two times, this is written as , and if it is filtered three times this is shown as .

2.2. Approximate Deconvolution

Deconvolution operators are often presented as the pseudo-inverse of a particular convolution operator. Thus, as its name would suggest, approximate deconvolution operators approximate such deconvolution operators. The deconvolution problem can be stated by first letting be a function over a suitable domain . Let be obtained by filtering by the differential filter in Definition 1. Let F denote the filtering operator. The deconvolution problem, as discussed in [15], becomes,

This approach approximates a deconvolution operator D through fixed point iteration. Due to its ease of implementation, to date, TRM models have exclusively utilized the van Cittert approximate deconvolution algorithms, which are described below. Alternative techniques do exist, and are proposed as open problems in Section 6.

Algorithm 1 (van Cittert Approximate Deconvolution).

Given a filter F, a filtered function assign , then for perform the fixed-point iteration,

We then call

This algorithm’s formulation can be simplified slightly, such that, given an order of deconvolution N,

Hence, the added precision is obtained through added extrapolation. The first few approximate-deconvolution operators can be written as,

3. Time Relaxation

Time relaxation techniques, in the context of turbulent fluid flow regularization, were introduced by Stolz et al. in [4,5]. Their formulation is considered a regularization of a Chapman–Enskog expansion [16,17], and was devised as a way to introduce added energy dissipation to A the approximate deconvolution models, a class of large eddy simulations. In [6], the authors instead introduced this time relaxation term to the unregularized NSE. Therein the linear TRM was first written:

This new class of models nudged computed solutions of the unregularized NSE toward the regularized flow . Existence and uniqueness were demonstrated in [6], along with regularity of strong solutions. It is also shown that the model is effective in dampening spatial fluctuations beneath without substantially altering the larger, dominant scales, particularly when high-order deconvolution is utilized. A nonlinear extension was also considered, i.e.,

This particular nonlinear relaxation model is a special case of the nonlinear TRM studied in [11]. It was argued that this quadratic extension presents a novel consistency with friction forcing, which is proportional to the square of the velocity.

3.1. Convergence of Weak Solutions of the Linear TRM to the NSE

Weak solutions to the linear TRM were shown to converge to weak solutions of the NSE in [7]. We will demonstrate that result here.

A variational formulation of the NSE can be written: Find , with satisfying,

The operator is self-adjoint and positive on X, [7]. Define B such that,

Therefore is well-defined, positive, and bounded. Next, select . We see,

Define the difference , then subtract (16) from (13) to see,

Test this equation with to see

Using Young’s inequality, Equation (21) becomes,

Applying Gronwall’s Lemma, then multiplying through by the integrating factor, , then using , we have,

i.e.,

Based on the above, the following lemma was stated.

Lemma 1.

This result guarantees a weak sense of limit consistency, i.e., if for a particular value of we call the linear TRM solution , then for any ,

3.2. The Effects of Time Relaxaiton on the Energy Cascade

In the linear case (9) and (10), a similarity study was also conducted in [6] revealing that if is selected appropriately, one will not only observe an energy cascade, but potentially control that cascade by inducing a new effective Kolmogorov micro-scale for (9) and (10) that agrees with the filtering length . This was called a “perfect resolution,” since in this case the extra dissipation perfectly balances the energy transfer from external power sources to the new cutoff scale while preventing a non-physical accumulation of energy there. This is accomplished by selecting,

where U is the global velocity scale, and L is the characteristic length scale of the domain. This results in and in turn guarantees, for deconvolution order N,

Forcing an accelerated dissipation to occur at a this larger length scale has the potential to substantially relax the spatial discretization requirements in numerical simulations. In 3D flows, the sufficient condition to fully resolve (9) and (10) is,

which is totally independent of . The savings can be estimated by the ratio,

This is a significant improvement, especially for flows presenting large Reynolds’ numbers.

3.3. A General Nonlinear Time Relaxation Extension

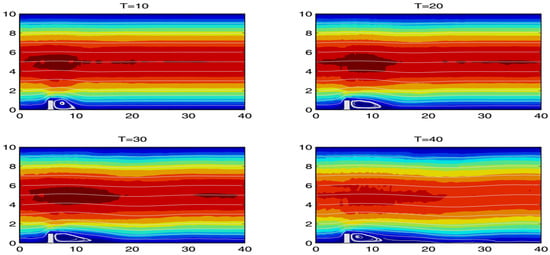

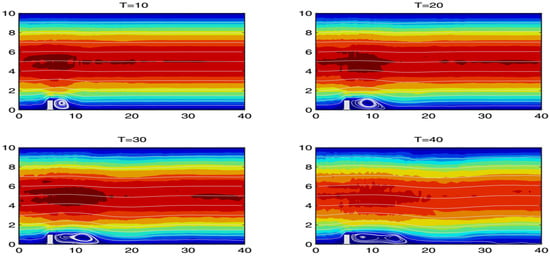

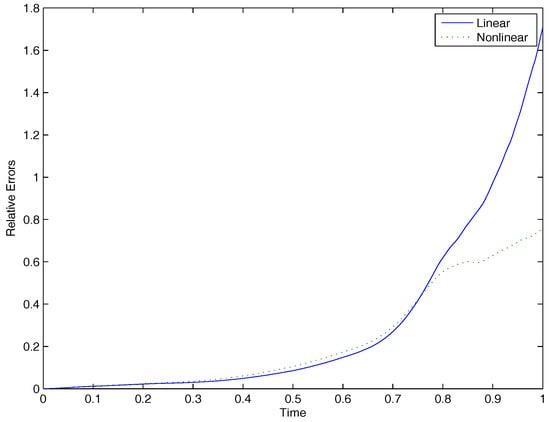

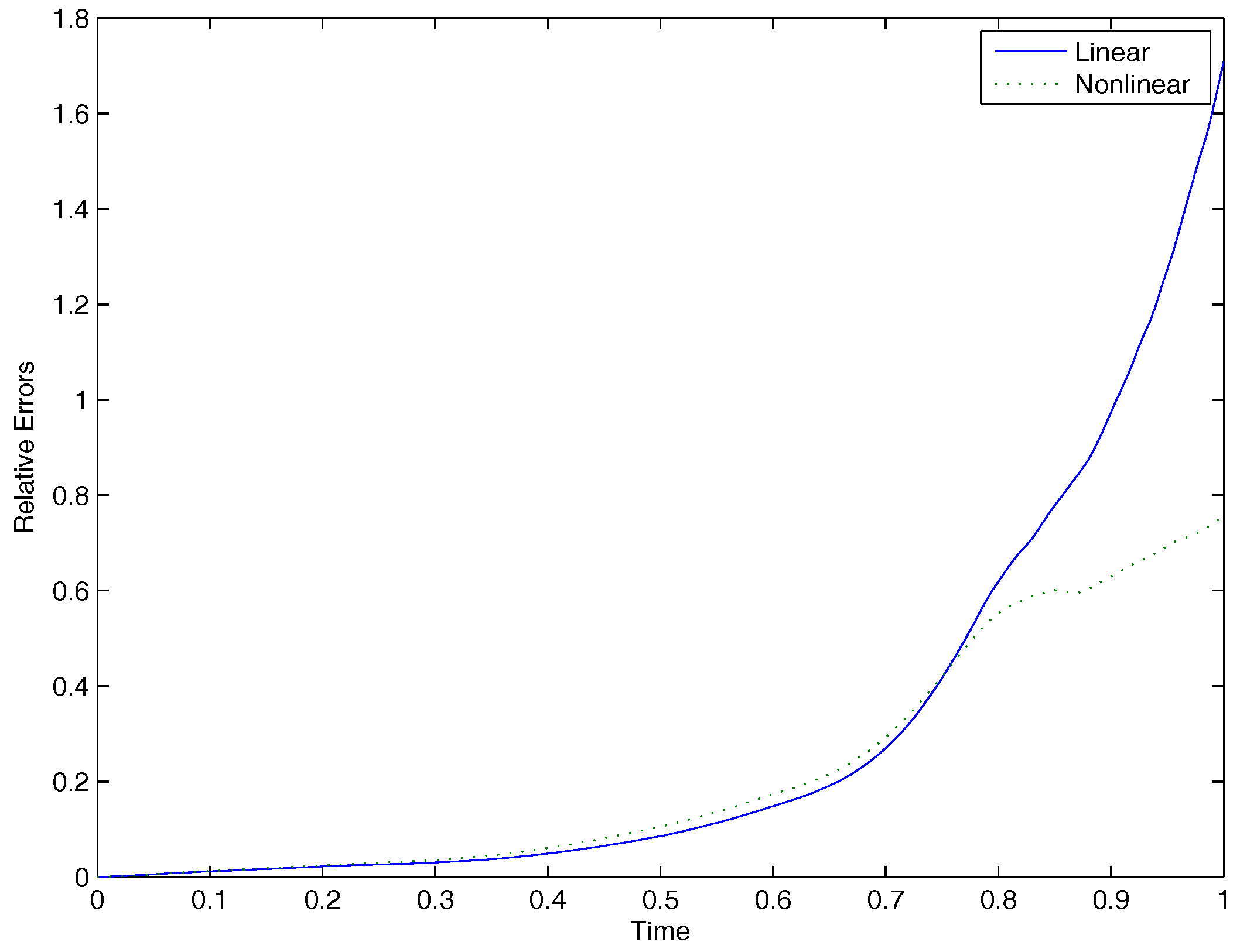

A natural extension to the nonlinear formulation seen in [6] and (11) and (12) is discussed in detail in [11]. The main motivational claim for exploring the extended nonlinear model is that it does a better job of regularizing flow at higher wave numbers. This is demonstrated with numerical results, and discussed further in Section 4.

For , the time relaxation term is scaled such that,

Calculating the energy dissipation penalty for such models is a simple endeavor. If we let represent the energy dissipation penalty functional, in inviscid L-periodic flow on the cube , we find that for the linear case,

While this is fairly simple, if we note that the approximate deconvolution operators are self-adjoint, in the same settings, the energy dissipated by the generalized nonlinear models is then given by,

Hence, it can be surmised from (27) and (29) that if differs significantly from a spatially-filtered , a greater penalty will be contributed to the energy dissipation rate; i.e., more energy will be dissipated. The nonlinear formulation stands to easily exaggerate that process for larger values of r.

5. Parameter-Sensitivity Study of the Time Relaxation Model

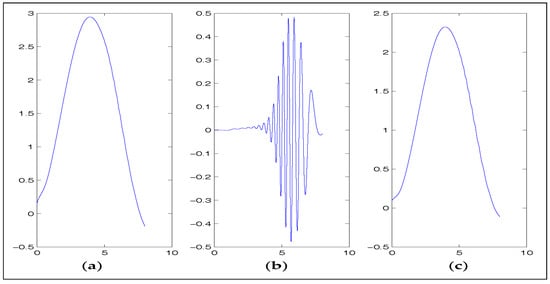

The “optimal” parameter choices for non-physical quantities like the relaxation coefficient , nonlinear time relaxation order r, and the filtering length are discussed [6,11,19]. That said, the notion of “optimal” scales for such parameters are inherently problem- and goal-specific. This is further complicated by the fact computed solutions are inherently sensitive to these parameters.

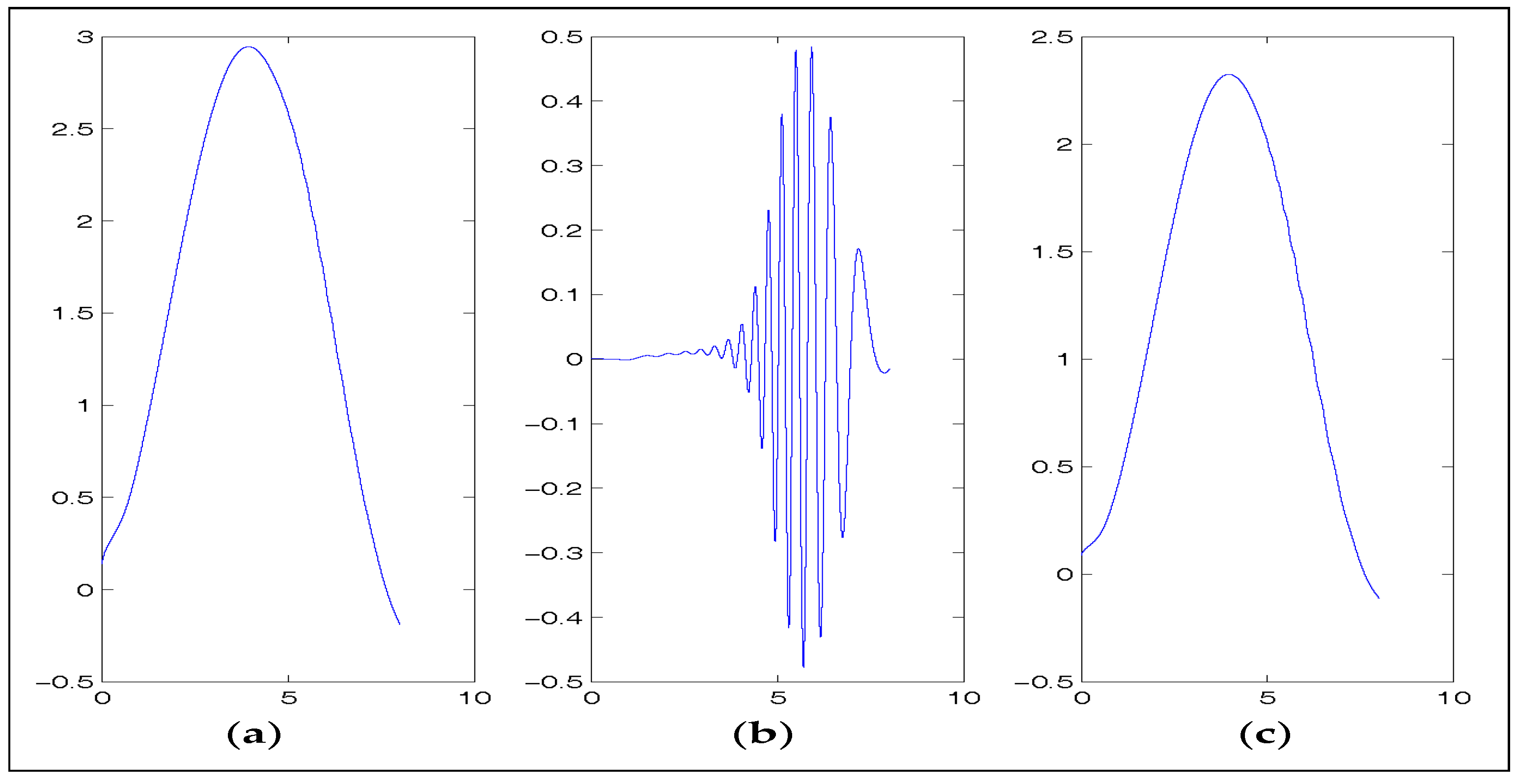

The notion of sensitivity for the linear time relaxation model was addressed in [22]. Since it is understood that a velocity solution to the linear model is sensitive to perturbations of , we denote velocity solutions to the linear TRM for a given as The solution results in a direct numerical simulation of the NSE. We can estimate sensitivity by the forward finite difference (FFD)

Further, if we assume varies smoothly with , we can define the sensitivity as the implicit derivative,

We similarly define the sensitivity of pressure as , and filtered velocity .

The sensitivity is evaluated in two ways. Firstly, the FFD method (36) can be used and secondly, the sensitivity equation method (SEM) can also be used. The SEM is developed by taking an implicit derivative of (9) and (10), as well a the filter Equation (5). For simplicity, we let then by selecting , the sensitivity equations are written:

Initial and boundary conditions for (9) and (10) are inherently insensitive to , hence for all implementations,

The new PDE (38)–(40) is discretized and computed in conjunction with the model’s discretization. In [22] the SEM equations are discretized using the same scheme, Taylor–Hood finite elements, and Crank–Nicolson time stepping. For notational clarity, in the discussion of the Crank–Nicolson temporal discretization, we let for the continuous variable and for both, continuous and discrete variables. Thus, we obtain the following discretized finite element variational formulations.

Given , end-time , the time step is chosen , find the approximated TRM solution , for satisfying,

and the sensitivity solution , for satisfying,

Find , for satisfying,

and for the sensitivity solution, find , for satisfying,

The sensitivity is evaluated on several benchmark problems that consider a variety of mesh scales and Reynolds numbers. Each sensitivity calculation is computed by both the FFD and SEM techniques. One such benchmark is the 2D lid-driven cavity problem where , and . The initial and boundary conditions for the linear TRM velocity are given by,

The sensitivity estimates are enumerated in Table 3 and Table 4. It is with these values that one can determine the reliability of a the linear time relaxation model when .

Table 3.

Computations of for the lid-driven cavity problem.

Table 4.

Computations of for the lid-driven cavity problem.

5.1. Comparing the SEM and FFD Methods

In [22], the authors used both the SEM and FFD techniques, under the assumption they would provide similar results in the tested settings. This appears to have been done as a form of sanity check. Neither technique demonstrates an overall advantage. For instance, both methods require effectively doubling all computational efforts by solving a second system of equations. Both methods are also easily implemented in working code bases.

The only situation that would necessitate the use of FFD over the SEM is if there is good reason to doubt the existence of the implicit derivatives in (37). On the other hand, a FFD computation is effectively meaningless if the case is unstable or otherwise unreliable, which is not uncommon in under-resolved flows at higher Reynolds numbers. The choice of implementing one technique over the other is largely problem-specific, and a question best left to the good judgment of future authors.

5.2. Determining Reliability of Time-Relaxation Models through Sensitivity Study

As mentioned at the beginning of this section, determining an optimal choice of is a difficult endeavor. Sensitivity studies can be used with great effect to help quantify the reliability of such calculations. While [22] did not explore particular methods to directly quantify model reliability, examples can be found in [23,24]. One such technique is to quantify reliability by using the linear estimate,

The above estimate holds for any norm.

If, for example, the total kinetic energy of a particular flow is known or can be accurately estimated, enforcing a accuracy as an upper bound can determine permissible intervals of model-reliability. Likewise, if for a given norm, the goal is for the computed results of the TRM model to be accurate to within 5% of , we simply attempt to find an interval such that,

To date, this type of study has not been performed on time relaxation models, and would make for interesting future work.

6. Conclusions and Open Problems

Herein we have presented a summary of a selection of published results about and relevant to time relaxation models. We briefly introduced the technique and the motivations for their development, as well as the results from several computational implementations. While numerous studies have been performed in literature, a number of open questions remain.

Much of the numerical results surveyed herein use the Crank–Nicolson time-stepping scheme. The behavior of linear and nonlinear TRMs with alternate time-stepping schemes, like BDF2 or schemes that permit a variable time-step, remains an open problem. Higher-order time-stepping schemes have also not been considered.

It would be interesting to see the extent to which the energy dissipation penalty for the nonlinear TRM parameter, as determined by and r, affects the energy cascade. Furthermore, numerical experiments have not been seen for nonlinear orders greater than the quadratic case, .

In fluid flow problems, approximate deconvolution has been largely accomplished by the van Cittert approximate deconvolution technique. Other techniques exist, i.e. Guerts approximate inverse operators [25], and others. Time relaxation models would be an excellent test bed for such studies, given their simplicity.

So far, the only parameter sensitivity investigation for TRMs was performed in [22], wherein analysis and experiments to estimate sensitivity were done. It would be interesting to see a full analysis of the and sensitivities for both the linear and nonlinear TRMs. It would also be interesting to see how these parameters affect the outcomes of important functionals, i.e. forces acting on submerged bodies like lift and drag, or physical quantities like energy, enstrophy, helicity, and their dissipations. Finally, a full investigation into the reliability of time relaxation models in challenging computational settings would be of particular interest. This is briefly discussed in Section 5.2.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kistler, R. A Study of Data Assimilation Techniques in an Autobarotropic Primitive Equation Channel Model. Master’s Thesis, Penn State University, State College, PA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Hoke, J.; Anthes, R. The initialization of numerical models by a dynamic-initialization technique. Mon. Weather Rev. 1976, 104, 1551–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolmogorov, A. The local structure of turbulence in incompressible viscous fluids for very large Reynolds numbers. Dokl. Akad. Nauk SSR 1941, 30, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolz, S.; Adams, N.; Kleiser, L. The approximate deconvolution model for large-eddy simulations of compressible flows and its application to shock-turbulent-boundary-layer interaction. Phys. Fluids 2001, 13, 2985–3001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolz, S.; Adams, N.; Kleiser, L. An approximate deconvolution model for large-eddy simulation with application to incompressible wall-bounded flows. Phys. Fluids 2001, 13, 997–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layton, W.; Neda, M. Truncation of scales by time relaxation. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2007, 325, 788–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ervin, V.; Layton, W.; Neda, M. Numerical analysis of a higher order time relaxation model of fluids. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Model. 2007, 4, 648–670. [Google Scholar]

- Neda, M. Discontinuous time relaxation method for the time-dependent Navier-Stokes equations. Adv. Numer. Anal. 2010, 2010, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neda, M.; Sun, X.; Yu, L. Increasing accuracy and efficiency for regularized Navier-Stokes equations. Acta Appl. Math. 2012, 118, 57–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De, S.; Hannasch, D.; Neda, M.; Nikonova, E. Numerical analysis and computations of a high accuracy time relaxation fluid flow model. Int. J. Comput. Math. 2012, 89, 2353–2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunca, A.; Neda, M. Numerical analysis of a nonlinear time relaxation model of fluids. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2014, 420, 1095–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takhirov, A.; Neda, M.; Waters, J. Time relaxation algorithm for flow ensembles. Numer. Methods Partial Differ. Equ. 2016, 32, 757–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neda, M.; Waters, J. Finite element computations of time relaxation algorithm for flow ensembles. Appl. Eng. Lett. 2016, 1, 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Germano, M. Differential filters for the large eddy numerical simulation of turbulent flows. Phys. Fluids 1986, 29, 1755–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertero, M.; Boccacci, P. Introduction to Inverse Problems in Imaging; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenau, P. Extending hydrodynamics via the regularization of the Chapman–Enskog expansion. Phys. Rev. A 1989, 40, 7193–7196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schochet, S.; Tadmor, E. The regularized Chapman–Enskog expansion for scalar conservation laws. Arch. Ration. Mech. Anal. 1992, 119, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volker, J. Reference values for drag and lift of a two-dimensional time-dependent flow around a cylinder. Int. J. Numer. Methods Fluids 2004, 44, 777–788. [Google Scholar]

- Connors, J.; Layton, W. On the Accuracy of the Finite Element Method Plus Time Relaxation. Math. Comput. 2010, 79, 619–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecht, F. New development in FreeFem++. J. Numer. Math. 2012, 20, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, M.; Turek, S. The benchmark problem ‘flow around a cylinder’. In Flow Simulation with High-Performance Computers II, Notes on Numerical Fluid Mechanics; Vieweg + Teubner Verlag: Wiesbaden, Germany, 1996; Volume 52, pp. 547–566. [Google Scholar]

- Neda, M.; Pahlevani, F.; Waters, J. Sensitivity Analysis of the Time Relaxation Model. Appl. Math. Mech. 2015, 7, 89–115. [Google Scholar]

- Pahlevani, F.; Davis, L. Parameter Sensitivity of an Eddy Viscosity Model: Analysis, Computation, and It’s Application to Quantifying Model Reliability. Int. J. Uncertain. Quantif. 2013, 3, 397–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breckling, S.; Neda, M.; Pahlevani, F. Sensitivity Analyses of the Navier-Stokes-α Model. 2017. submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Geurts, B.J. Inverse modeling for large-eddy simulation. Phys. Fluids 1997, 9, 3585–3587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).