Particle Tracking Velocimetry Measurements and Simulations of Internal Flow with Induced Swirl

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

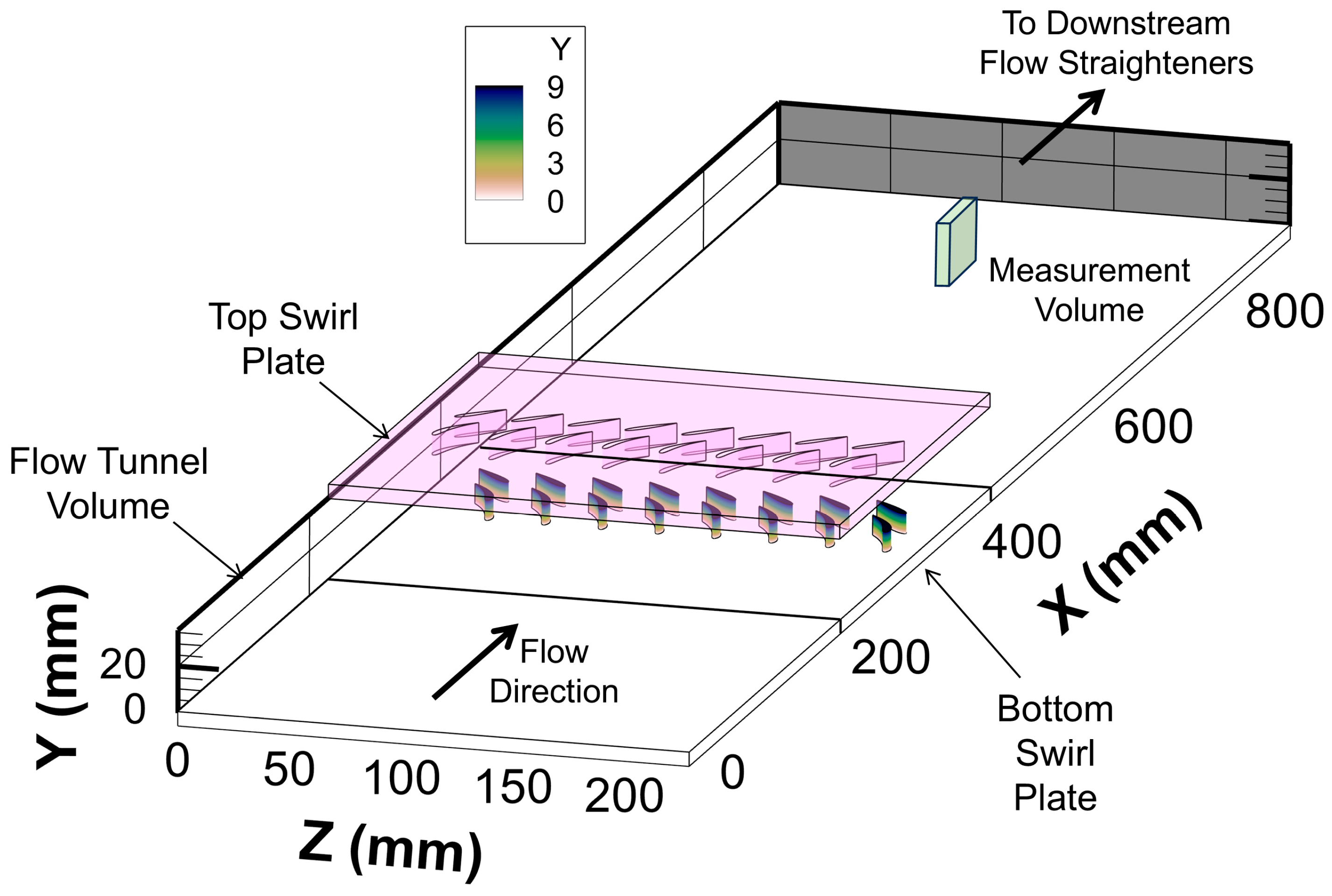

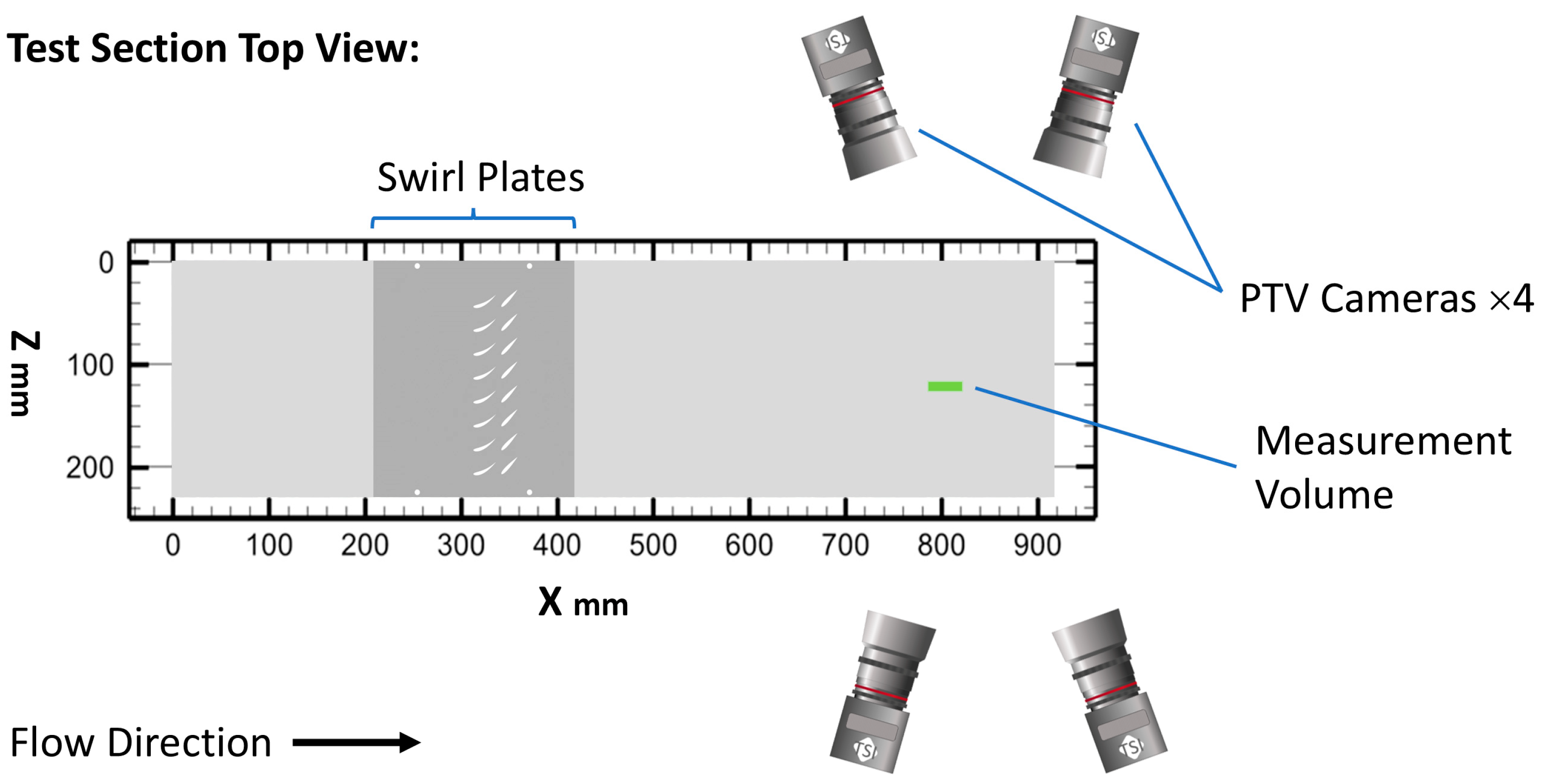

2.1. Roughness Internal Flow Tunnel (RIFT)

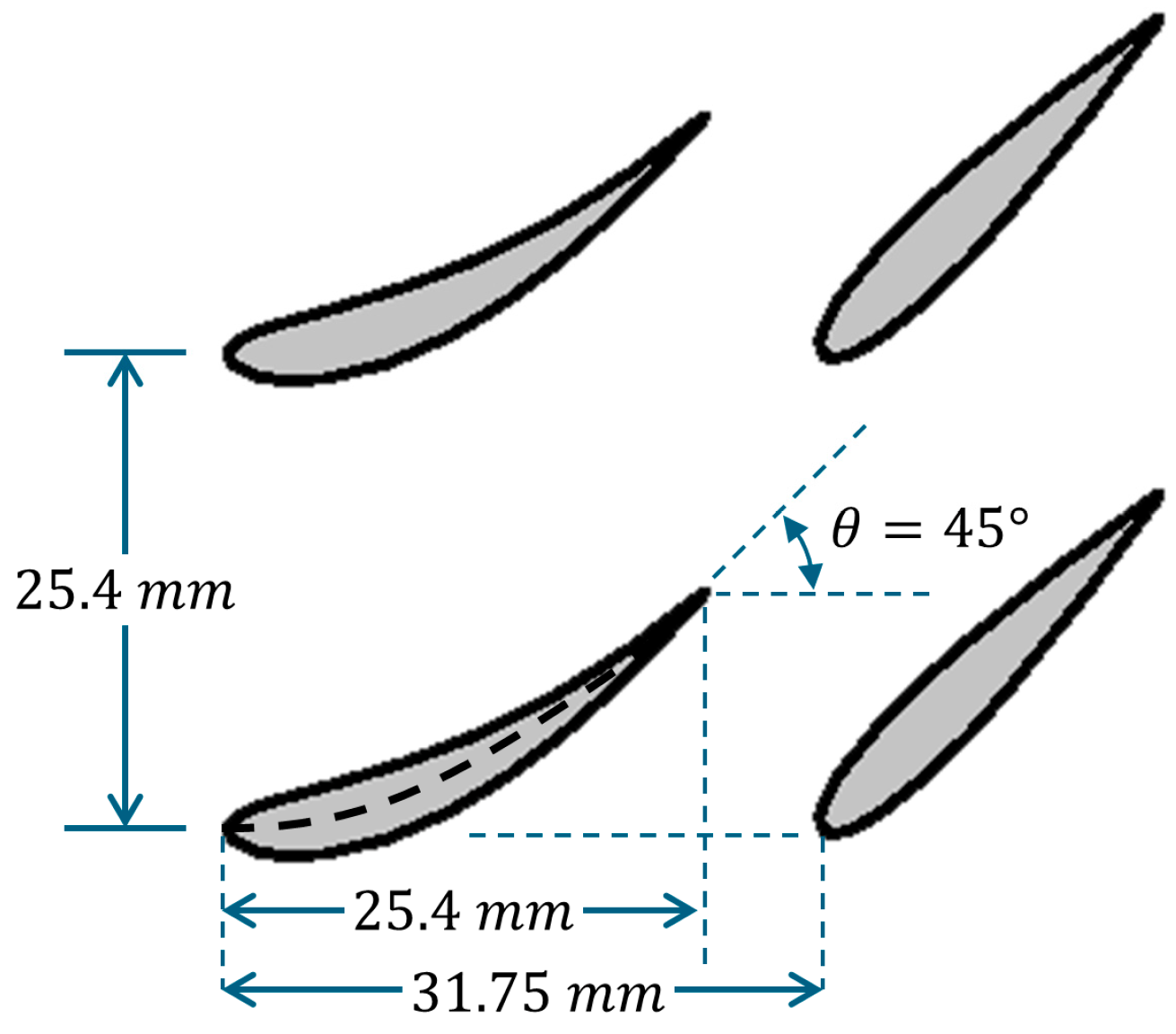

2.2. Swirl Plates

2.3. Particle Tracking Velocimetry (PTV) System

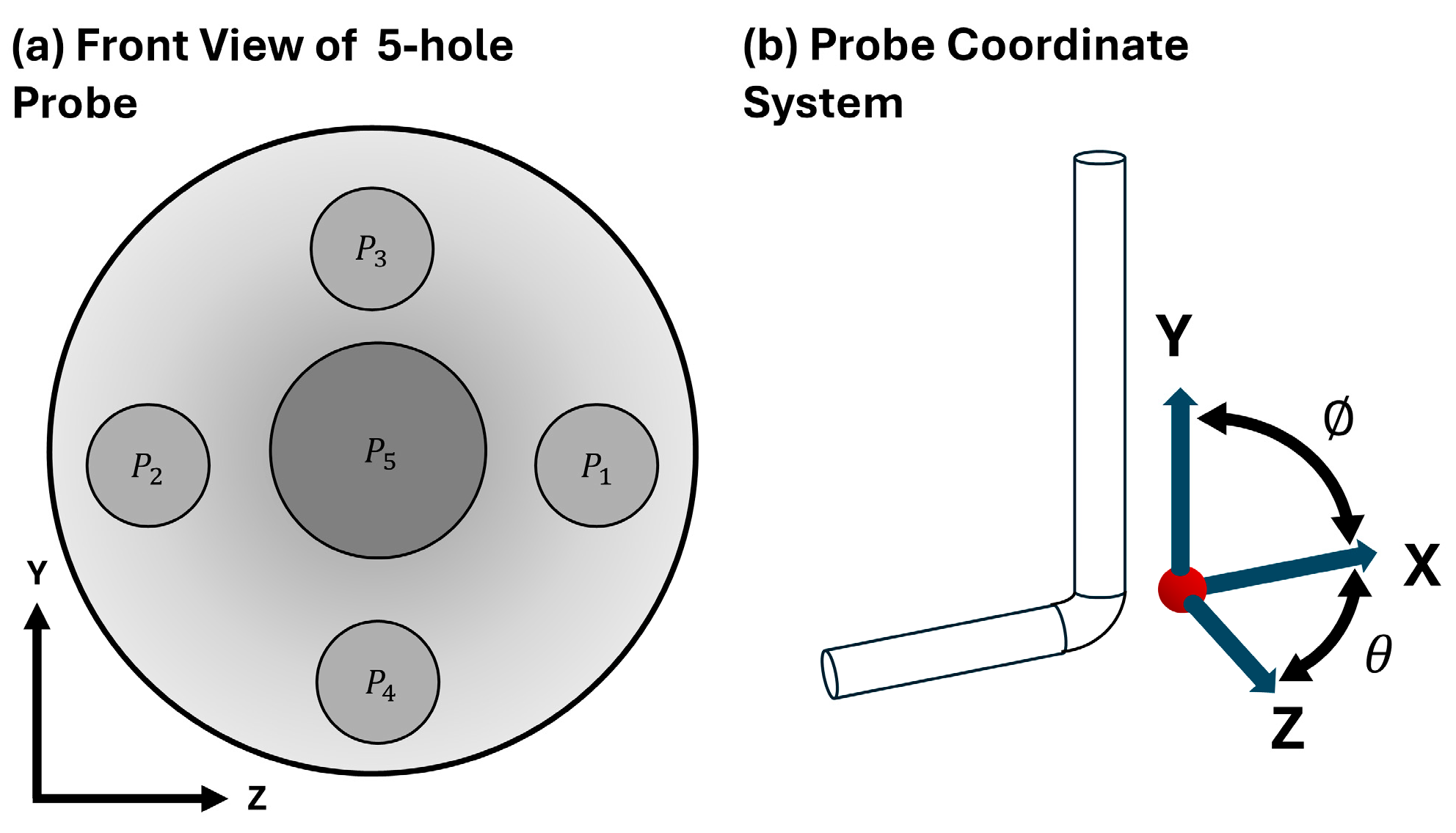

2.4. 5-Hole Probe

2.5. Swirl Number Calculation

2.6. Uncertainty Analysis

2.7. Simulation Methodology

3. Results

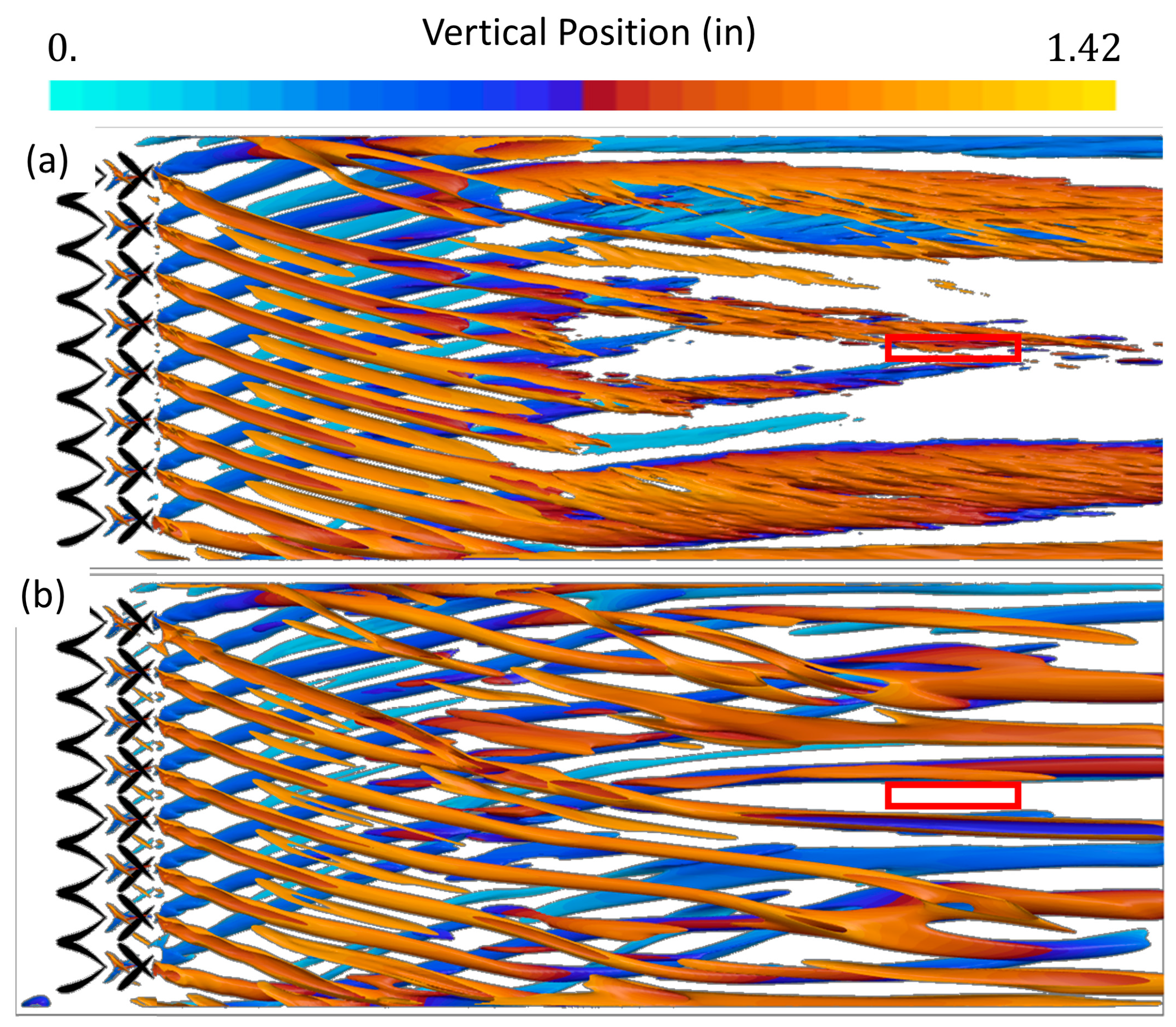

3.1. PTV Vector Clouds

3.2. PTV Velocity Profiles

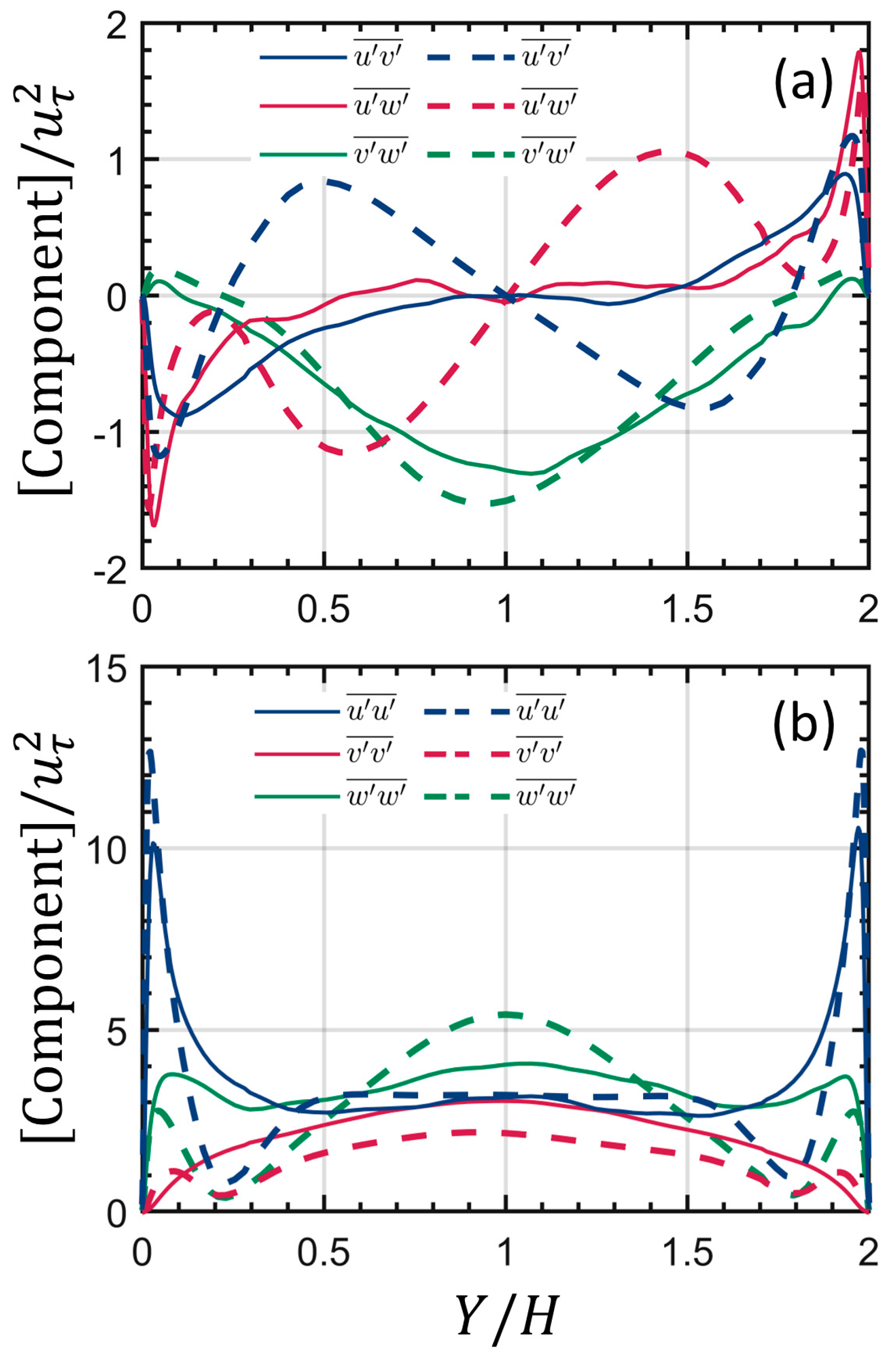

3.3. Swirl Strength

3.4. Simulation Results

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- The PTV system was employed to measure fluid rotation despite limitations in spanwise measurement uncertainty. The PTV measurements demonstrated similar variations as found in the five-hole probe measurements with the substantial benefit of characterizing an entire volume of ensemble-averaged swirling flow measurements.

- (2)

- The flow direction mean velocity profiles produced by the DES for flow within the measurement volume largely agree with measurements taken using the five-hole probe and PTV system.

- (3)

- Both RANS models underpredicted streamwise velocity at the channel midline.

- (4)

- The DES model underpredicts fluid rotation near the walls, but the maximum lateral flow agrees within 4% of the maximum channel streamwise (axial) flow.

- (5)

- The EB-RSM model predicts fluid rotation within 5% of the maximum channel streamwise flow despite underpredicting the centerline streamwise velocity by 15% of the maximum streamwise flow velocity.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RIFT test section cross-sectional area | |

| Systematic uncertainty of the x variable | |

| RIFT nozzle discharge coefficient = 0.915 | |

| Channel half-height (y-axis) | |

| Length of test section | |

| Random uncertainty of x variable | |

| Volumetric flow rate | |

| Reynolds number found with hydraulic diameter | |

| Spatially averaged mean velocity in x-direction | |

| Bulk streamwise velocity interacting with the smooth surface opposing the rough wall | |

| Bulk streamwise velocity interacting with the rough surface | |

| Bulk velocity tangential to the x-axis | |

| Bulk velocity in the x-direction | |

| Velocity tangential to the x-axis | |

| Velocity in the x-direction | |

| Density of air | |

| Viscosity of air | |

| Wall shear | |

| Pressure drop across test section | |

| time fluctuating quantity | |

| spatially averaged quantity | |

| time or volumetrically (bulk) averaged quantity |

References

- Vashahi, F.; Lee, S.; Lee, J. Experimental Analysis of the Swirling Flow in a Model Rectangular Gas Turbine Combustor. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 2016, 76, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.K.; Lilley, D.G.; Syred, N. Swirl Flow; Abacus Press: Tunbridge Wells, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Syred, N.; Beer, J.M. Combustion Swirling Flows: A Review. Combust. Flame 1974, 23, 143–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, C.; Chen, F.; Yu, T.; Cai, W.; Li, X.; Lu, X. Experimental study on flame/flow dyanmics in a multi-nozzle gas turbine model combustor under thermo-acoustically unstable condition with different swirler configurations. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2020, 98, 105692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.X.; Langella, I.; Swaminathan, N.; Stöhr, M.; Meier, W.; Kolla, H. Simulation of a dual swirl gas turbine combustor: Flame flow structures and stabilisation under thermosacoustically stable and unstable conditions. Combust. Flame 2019, 203, 279–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucca-Negro, O.; O’Doherty, T. Vortex breakdown; a review. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2001, 27, 431–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, J.; Zilliac, G.; Bradshaw, P. Mean and Turbulence Measurements in the Near Field of a Wingtip Vortex. AIAA J. 1997, 35, 1561–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algifri, A.H.; Bhardwaj, R.K.; Rao, Y.V.N. Prediction of the decay process of turbulent swirl flow. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. 1987, 201, 279–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fejer, A.; Lazan, A.; Wolf, L., Jr. Study of Swirilng Fluid Flows. 1968. Available online: https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/html/tr/AD0682529/ (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Kitoh, O. Experimental study of turbulent swiriling flow in a straight pipe. J. Fluid Mech. 1991, 225, 445–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattingly, G.E.; Yeh, T.T. NBS’ Industry-Goverment Consotium Research Rpogram on Flowmeter Insatllation Effects. Summary Report; National Bureau of Standards: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Mottram, R.C.; Rawat, M.S. The swirl damping properties of pipe-roughness and the implications for the orfice meters installation. In Proceedings of the Interational Conference on Flow Measurements, Glasgow, Scotland, 9–12 June 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Murakami, M.; Kito, O.; Katayama, Y.; Lida, Y. An experimental study of swirling flow in pipes. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 1976, 128, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nissan, A.; Bresan, V. Swirling flow in cylinders. Am. Institue Chem. Eng. 1961, 7, 543–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senoo, Y.; Nagata, T. Swirl flow in long pipes with different roughness. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 1972, 15, 1514–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhovich, E.P. Experimental investigation of local properties of swirled turbulent flow in cylindrical channels. Fluid Mech. Sov. Res. 1978, 7, 74–84. [Google Scholar]

- Weske, D.R.; Sturov, G.Y. Experimental study of turbulent swiled flows in a cylindrical tube. Fluid Mech. Sov. Res. 1978, 3, 74–84. [Google Scholar]

- Steenbergen, W.; Voskamp, J. The rate of decay of swirl in turbulent pipe flow. Flow Meas. Instrum. 1998, 9, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazuyoshi, M.; Yasutake, H.; Mizue, M. A study on swirling flow in a rectangular channel. J. Therm. Sci. 2001, 10, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, E.H.; Chu, W.X.; Ahmed, N.; Zeng, M. A new configuration of winglet longitudinal voertx generator to enhance heat transer in a rectangular channel. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2016, 104, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kito, O. Axi-asymmetric character of turbulent swirlng flow in a straight circular pipe. Bull. JSME April. 1984, 27, 683–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobota, T.; Marble, F. Swirling FLows in Annular-to-Rectangular Transition Section. J. Propuls. 1989, 5, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widenhorn, A.; Noll, B.; Stohr, M.; Aigner, M. Numerical Investigation of a Laboratory Combustor Applying Hybrid RANS-LES Methods. In Advances in Hybrid RANS-LES Modeling; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 152–161. [Google Scholar]

- Widenhorn, A.; Noll, B.; Aigner, M. Numerical Study of a Non-Reacting Turbulent Flow in a Gas Turbine Model Combustor. In Proceedings of the 47th AIAA Aerospace Sciences, Orlando, FL, USA, 5–8 January 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mansouri, Z.; Boushaki, T. Investigation of Large-Scale Structures of Annular Swirling Jet in a Non-Premixed Burner using Delayed Detached Eddy Simulation. Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow 2019, 77, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paik, J.; Sotiropolous, F. Numerical Simulation of Strongly Swirling Turbulent Flows through an Abrupt Expansion. Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow 2010, 31, 390–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yang, R.; Huang, Z.; Li, G.; Qin, X.; Li, J.; Wu, X. Detached Eddy Simulation on the Structure of Swirling Jet Flow Field. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2022, 49, 929–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClain, S.T.; Hanson, D.R.; Emily, C.; Snyder, J.C.; Kunz, R.F.; Thole, K.A. Flow in a simulated turbine blade cooling channel with spatially varying roughness caused by additive manufacturing orientation. J. Turbomach. 2021, 143, 071013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stafford, G.J.; McClain, S.T.; Hanson, D.R.; Kunz, R.F.; Thole, K.A. Convection in scaled turbine internal cooling passages with additive manufacturing roughness. J. Turbomach. 2023, 144, 041008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldt, R.; McClain, S.T.; Kunz, R.F.; Xiang, Y. Tomographic Flow Measurements Over Additively Manufactured Cooling Channel Roughness. Exp. Fluids 2024, 65, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldt, R.; McClain, S.T.; Kunz, R.F. Flow through a Passage with Scaled Additive Manufacturing Roughness Representing Different Printing Orientations. J. Fluids Eng. 2024, 146, 121203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TSI Inc. Insight V3V 4G Softare for Volumetric 3-Component Velocimetry Flow Measurement Systems; TSI Incorporated: Shoreview, MN, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, W.; Pan, G.; Menon, R.; Troolin, D.; Graff, E.; Gharib, M.; Pereira, F. Volumetric three-component velocimetry: A new tool for 3d flow measurement. In Proceedings of the 14th International Symposium on Application of Laser Techniques to Fluid Mechanics, Lisbon, Portugal, 7–10 July 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hamed, A.M.; Gallary, R.M.; McAtee, B.R. Localized Blowing for Near-Wake Flow and Vortical Structure Control in Turbulent Boundary Layers Over Periodic Two-Dimensional Roughness. ASME J. Fluids Eng. 2024, 146, 034502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, G.L.; Schobeiri, M.T.; Pappu, K.R. Five-hole pressure probe analysis technique. Flow Meas. Instrum. 1998, 23, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignat, G.; Durox, D.; Candel, S. The suitability of different swirl number deffinitions for describing swirl flows: Accurate, common and (over-) simplified formulations. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2022, 89, 100969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.-C.; Tien, W.-H.; Duncan, J.; Paul, M.; Ponchaut, N.; Mouton, C.; Dabiri, D.; Rösgen, T.; Hove, J. A vision-based hybrid particle tracking velocimetry (PTV) technique using a modified cascade correlation peak-finding method. Exp. Fluids 2012, 53, 1251–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, H.W.; Steele, W.G. Experimentation and Uncertainty Analysis for Engineers, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Moffat, R.J. Describing the Uncertainties in Experimental Results. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 1988, 1, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shur, M.L.; Spalart, P.; Strelets, M.K.; Travin, A.K. A hybrid RANS-LES approach with delayed-DES and wall-modelled LES capabilities. Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow 2008, 29, 1638–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menter, F. Two-Equation Eddy-Viscosity Turbulence Modeling for Engineering Applications. AIAA J. 1994, 43, 1598–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arolla, S.K.; Durbin, P.A. Modeling rotation and curvature effects within scalar eddy viscosity model framework. Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow 2013, 39, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manceau, R.; Hanjalic, K. Elliptic Blending Model: A New Near-Wall Reynolds-Stress Turbulence Closure. Phys. Fluids 2002, 14, 744–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lardeau, S.; Manceau, R. Computations of Complex Flow Configurations Using a Modified Elliptic-Blending Reynolds-Stress Model. In Proceedings of the 10th International ERCOFTAC Symposium on Engineering Turbulence Modeling and Measurements, Marbella, Spain, 17–19 September 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Churchfield, M.; Blaisdell, G. Reynolds Stress Relaxation Turbulence Modeling Applied to a Wingtip Vortex Flow. AIAA J. 2013, 51, 2643–2655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revell, A.; Iaccarino, G.; Wu, X. Advanced RANS Modeling of Wingtip Vortex Flows. In Proceedings of the Summer Program 2006; Center for Turbulence Research: Stanford, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

| 10,000 | 0.4070 | 0.1880 |

| 20,000 | 0.4893 | 0.3367 |

| 30,000 | 0.5556 | 0.3193 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Boldt, R.; Hanson, D.R.; Jiang, L.; McClain, S.T. Particle Tracking Velocimetry Measurements and Simulations of Internal Flow with Induced Swirl. Fluids 2025, 10, 323. https://doi.org/10.3390/fluids10120323

Boldt R, Hanson DR, Jiang L, McClain ST. Particle Tracking Velocimetry Measurements and Simulations of Internal Flow with Induced Swirl. Fluids. 2025; 10(12):323. https://doi.org/10.3390/fluids10120323

Chicago/Turabian StyleBoldt, Ryan, David R. Hanson, Lulin Jiang, and Stephen T. McClain. 2025. "Particle Tracking Velocimetry Measurements and Simulations of Internal Flow with Induced Swirl" Fluids 10, no. 12: 323. https://doi.org/10.3390/fluids10120323

APA StyleBoldt, R., Hanson, D. R., Jiang, L., & McClain, S. T. (2025). Particle Tracking Velocimetry Measurements and Simulations of Internal Flow with Induced Swirl. Fluids, 10(12), 323. https://doi.org/10.3390/fluids10120323