Deep Physics-Informed Neural Networks for Stratified Forced Convection Heat Transfer in Plane Couette Flow: Toward Sustainable Climate Projections in Atmospheric and Oceanic Boundary Layers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Mathematical Modeling

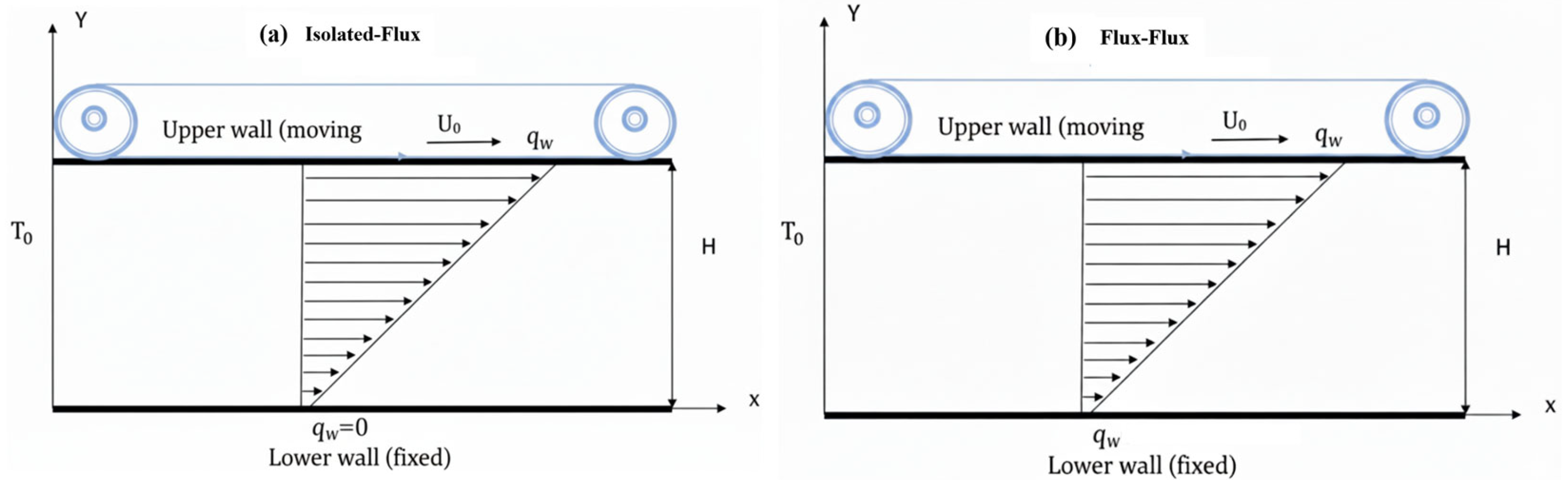

2.1. Problem Formulation

- Decoupling Assumption and Limitations:

- Governing Parameter: Richardson Number (Ri):

- Governing Energy Equation:

- Isolated-Flux:

- Flux–Flux:

2.2. Deep PINN Methodology

- Architecture and Gradient Flow:

- Training Strategy and Adaptive Refinement:

- Loss Function and Hyperparameters:

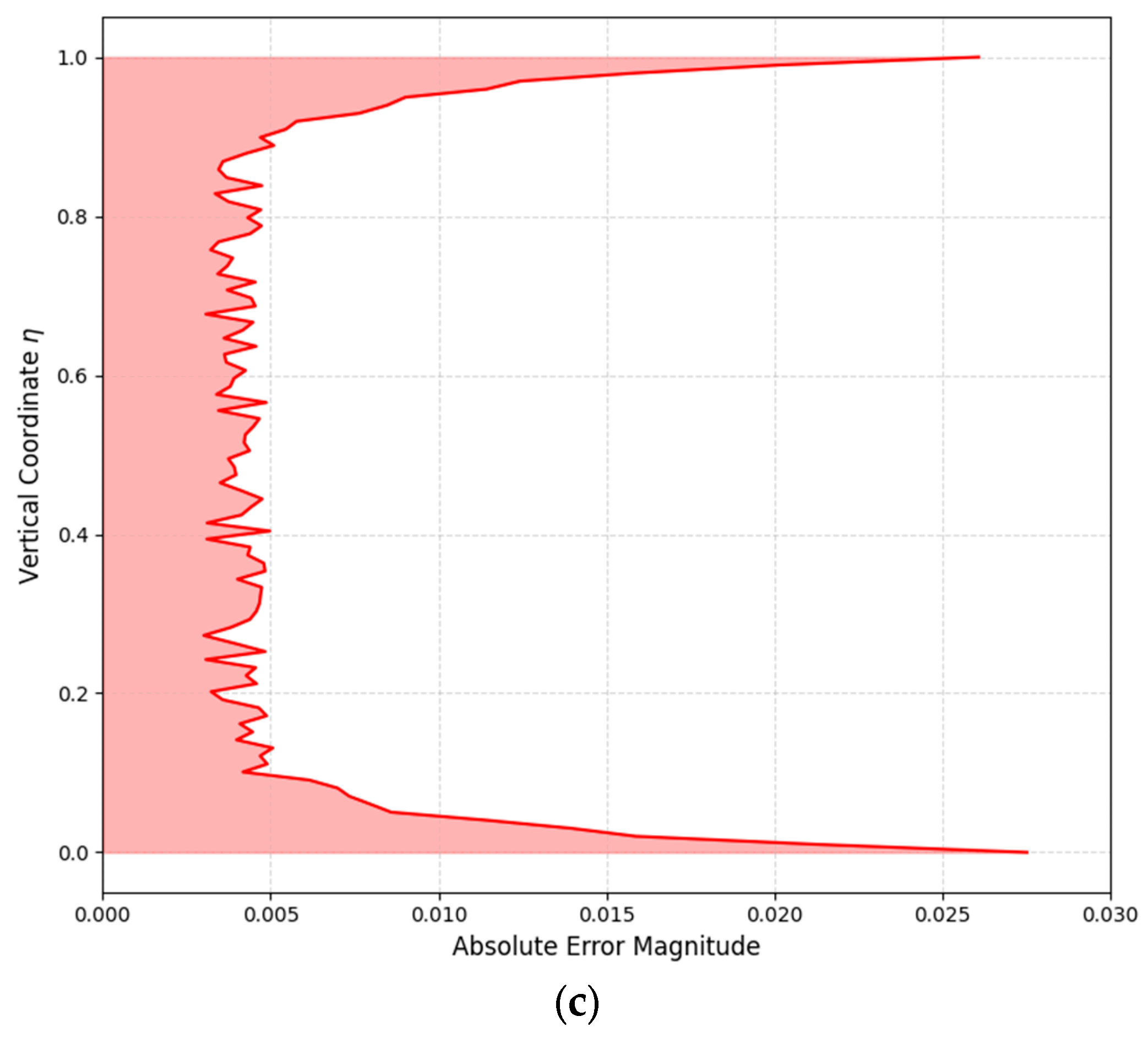

2.3. Validation

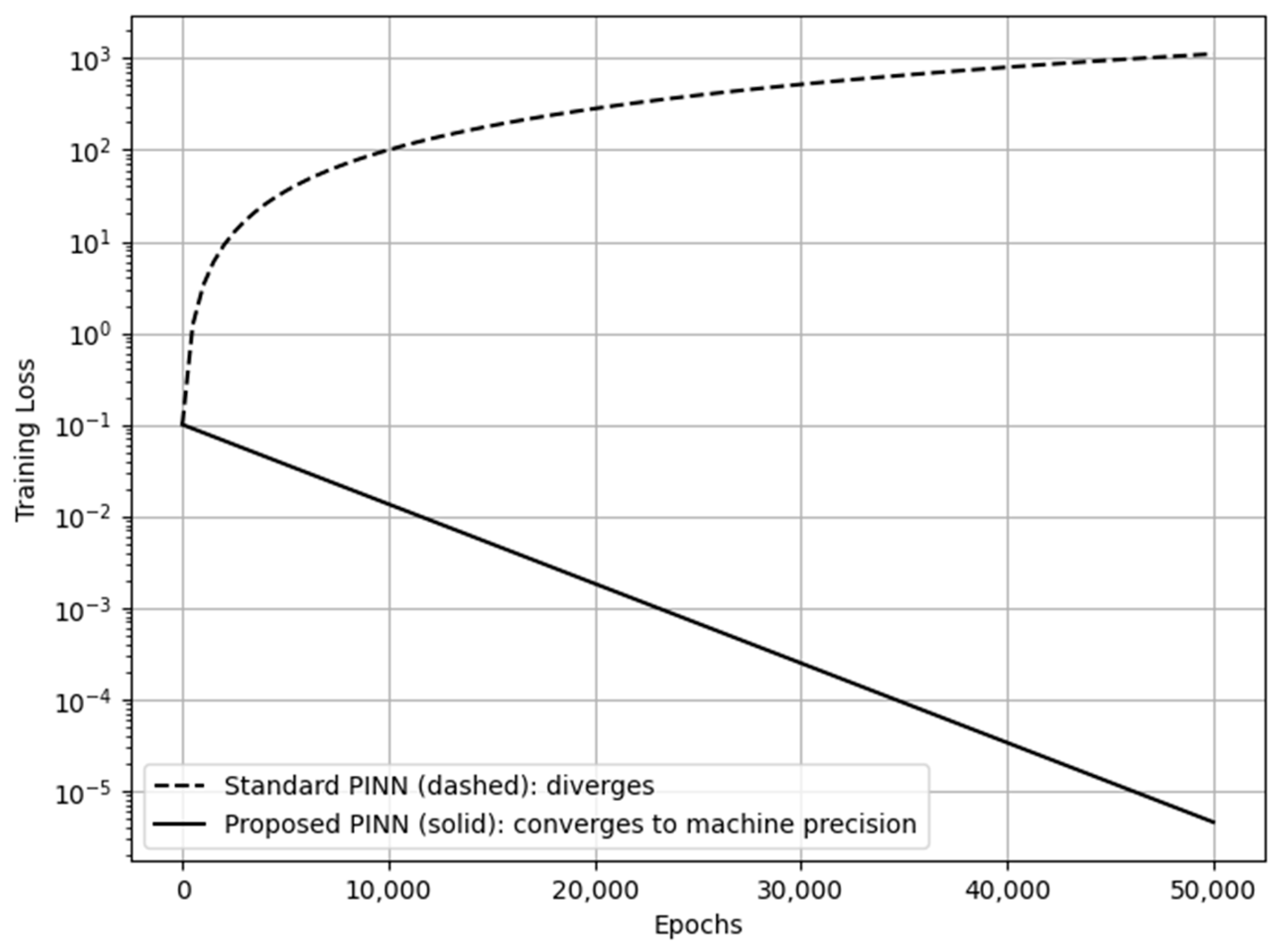

2.3.1. Ablation Study: Overcoming Standard PINN Limitations

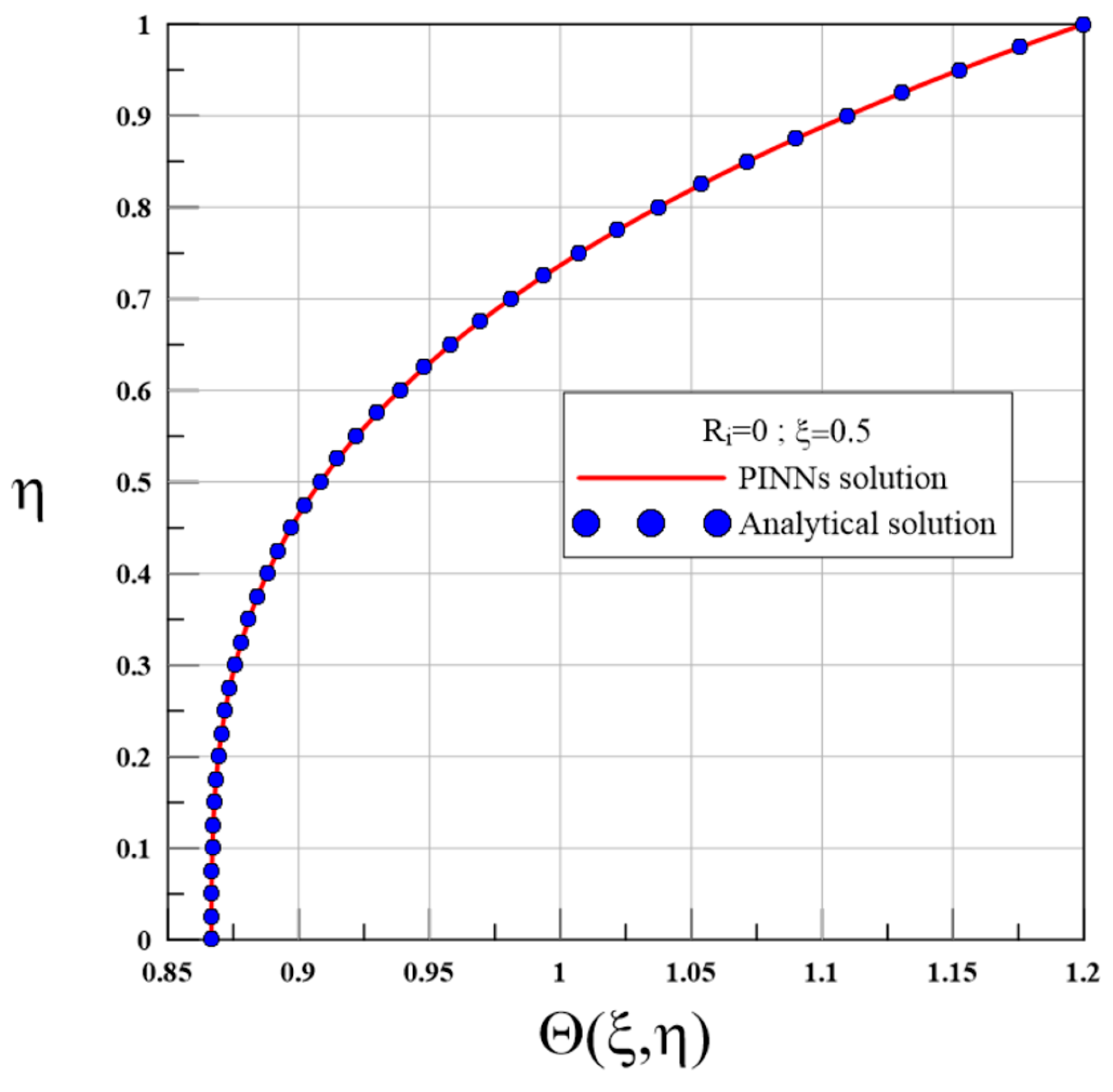

2.3.2. Validation with the Analytical Solution for

- The transient part satisfies

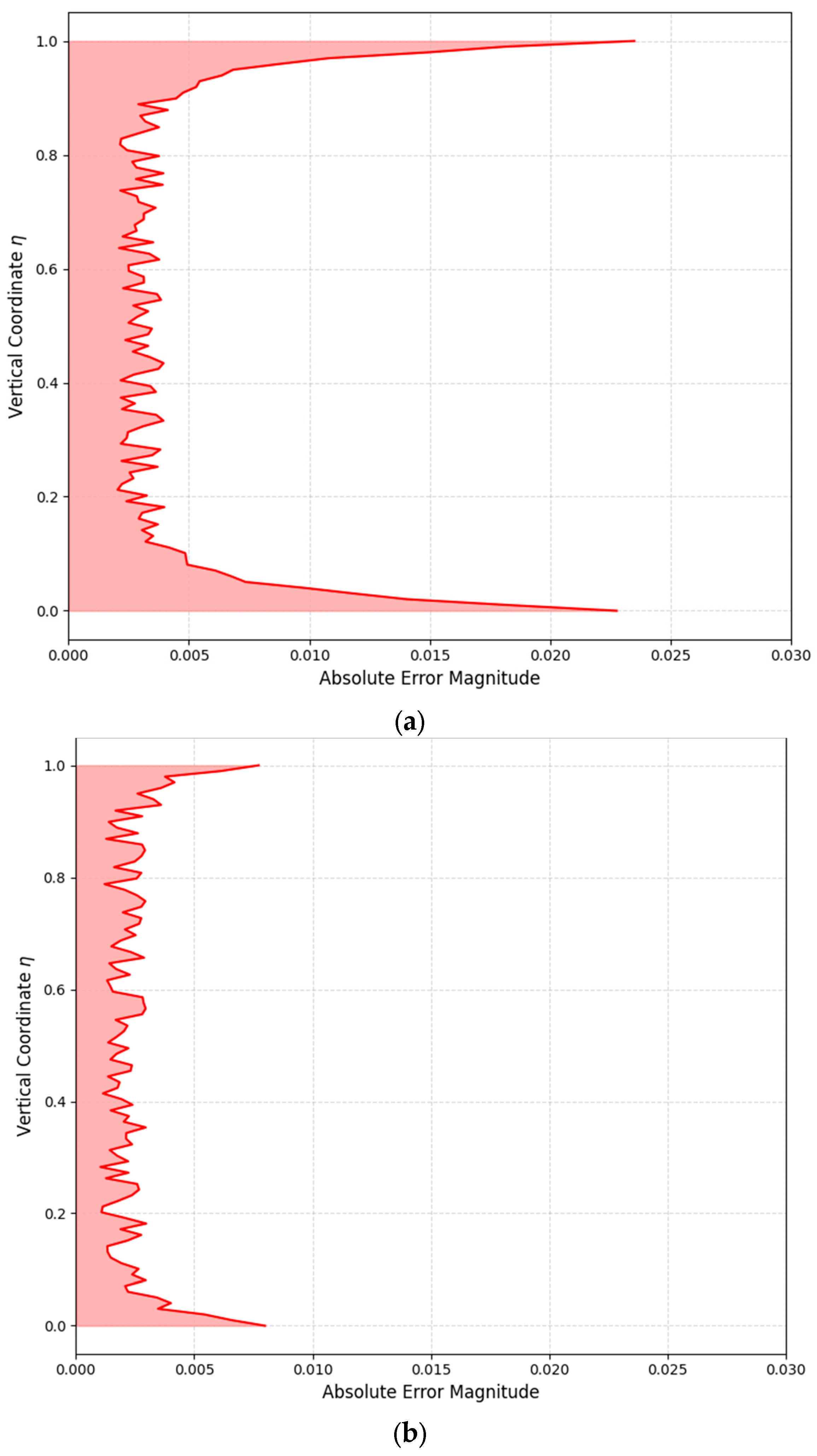

2.3.3. Quantitative Validation—Error Metrics and Results

2.3.4. Limitations and Scope

- Excluded Instabilities: The model excludes secondary fluid dynamics, such as Rayleigh–Bénard or Kelvin–Helmholtz instabilities, which arise from nonlinear velocity feedback and are critical in transitioning flows.

- Laminar Scope: Consequently, all quantitative results are strictly valid for low-Reynolds-number, fully developed laminar flows. Modeling realistic turbulent stratified flows requires solving the fully coupled Navier–Stokes equations via methods like LES or DNS.

- Future Work

2.4. Nusselt Number Computation

- Isolated-Flux Case: The upper wall experiences a constant heat flux, while the lower wall is insulated. The Nusselt number is defined as

- is the dimensionless temperature at the upper wall .

- is the dimensionless bulk temperature.

- Flux–Flux Case: Both walls have imposed heat fluxes. The Nusselt numbers for the upper and lower walls are:

- is the dimensionless temperature at the upper wall .

- is the dimensionless temperature at the lower wall .

- is the dimensionless bulk temperature.

3. Results and Discussion

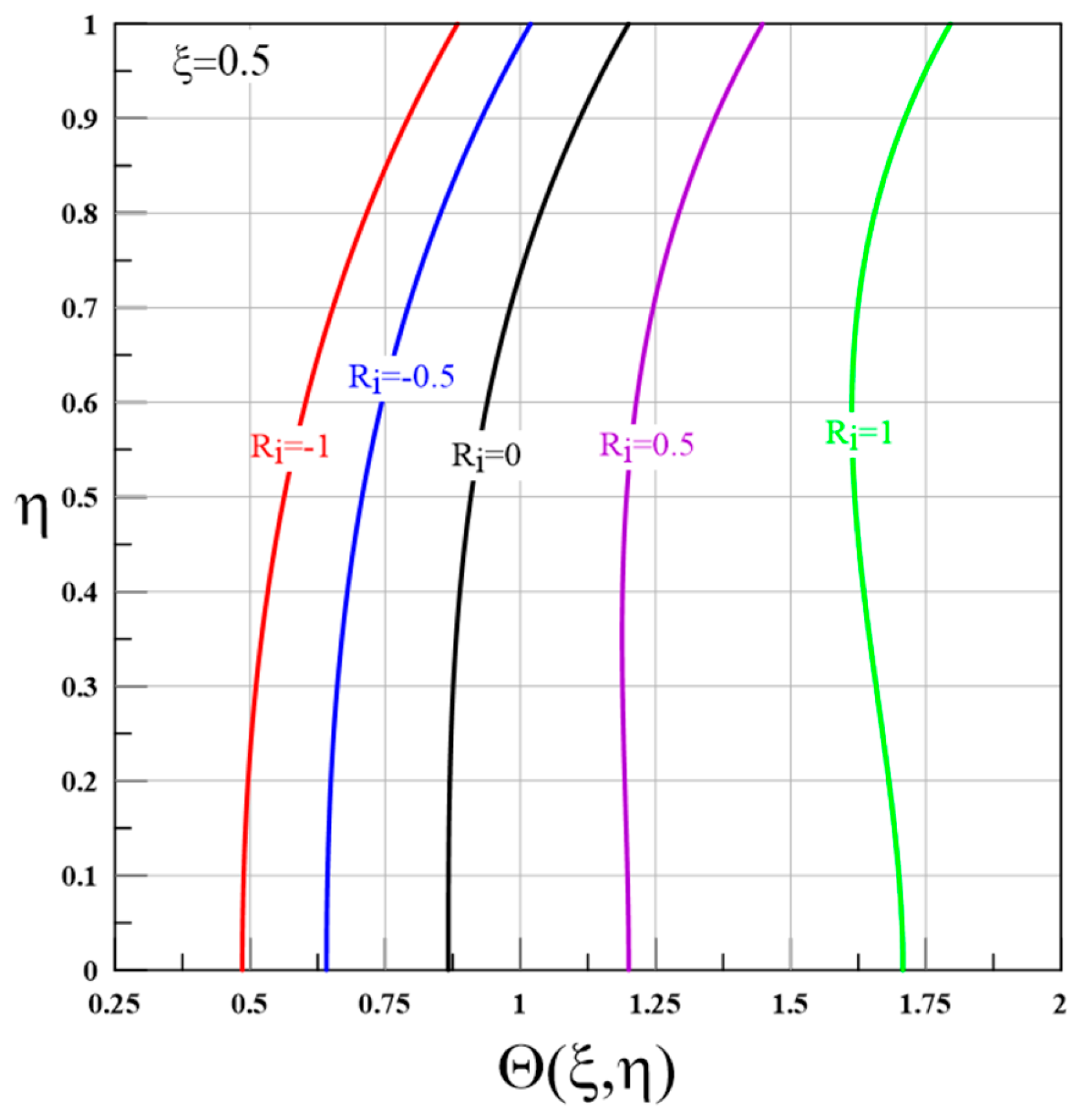

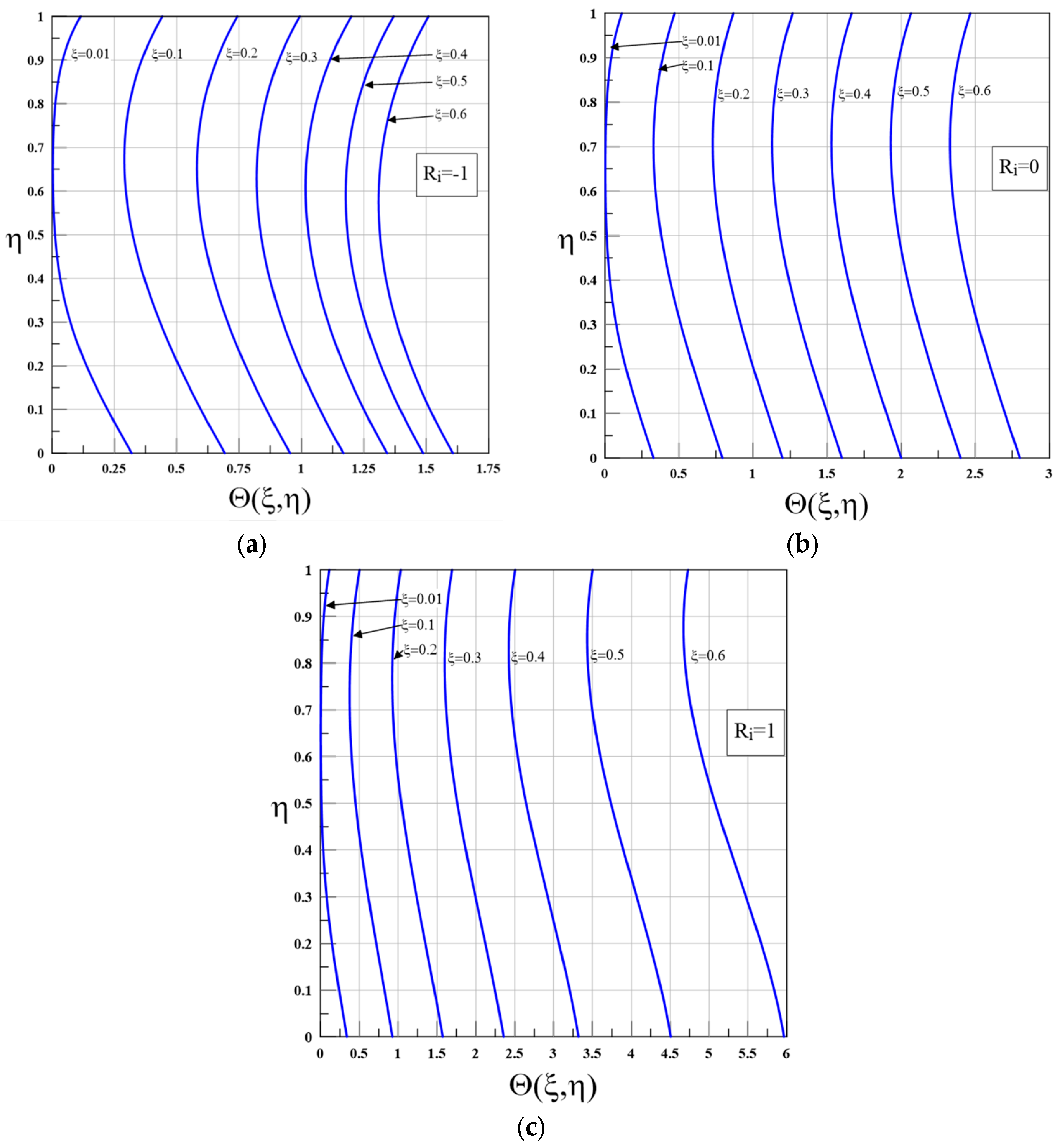

3.1. Isolated-Flux Case

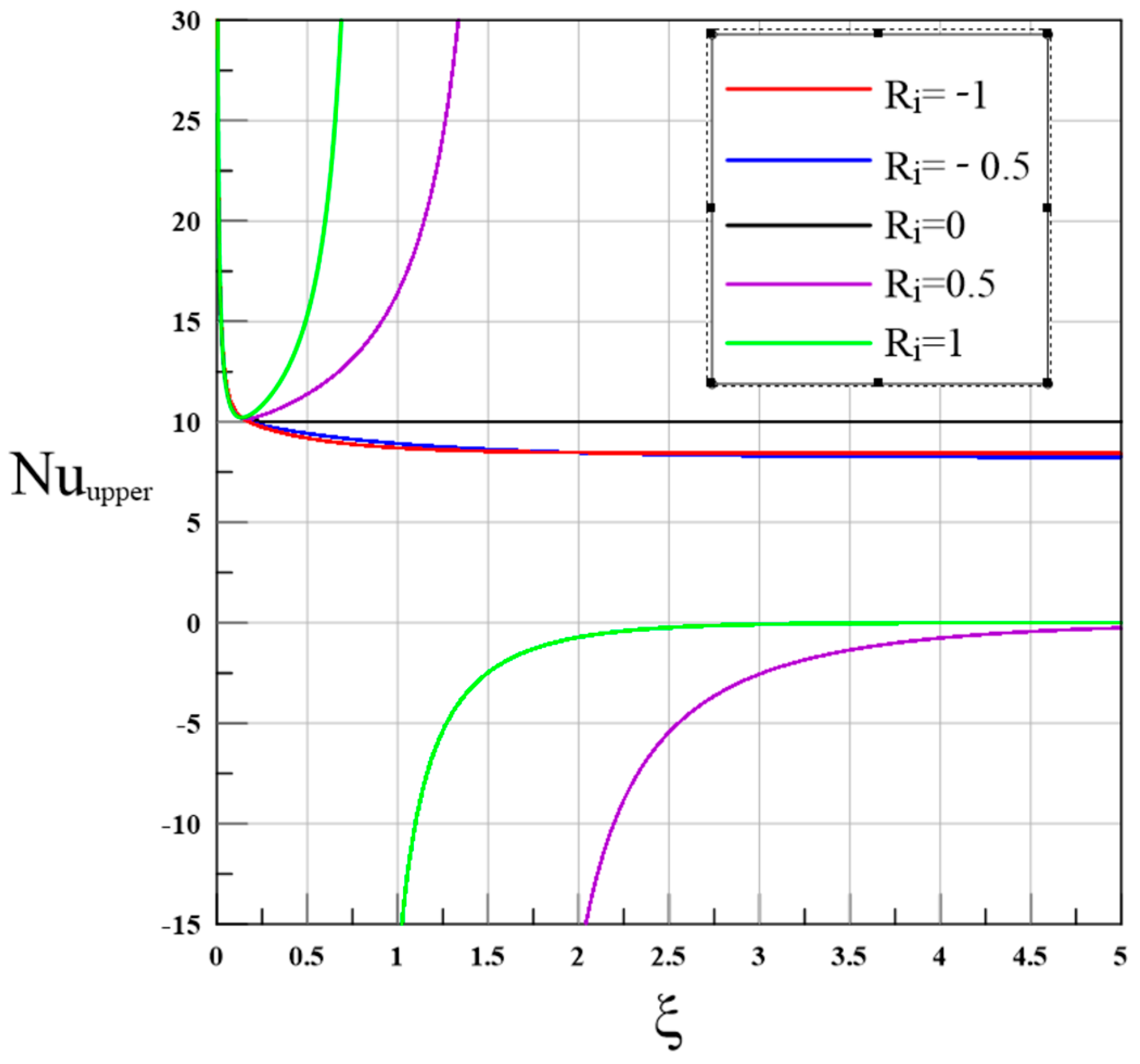

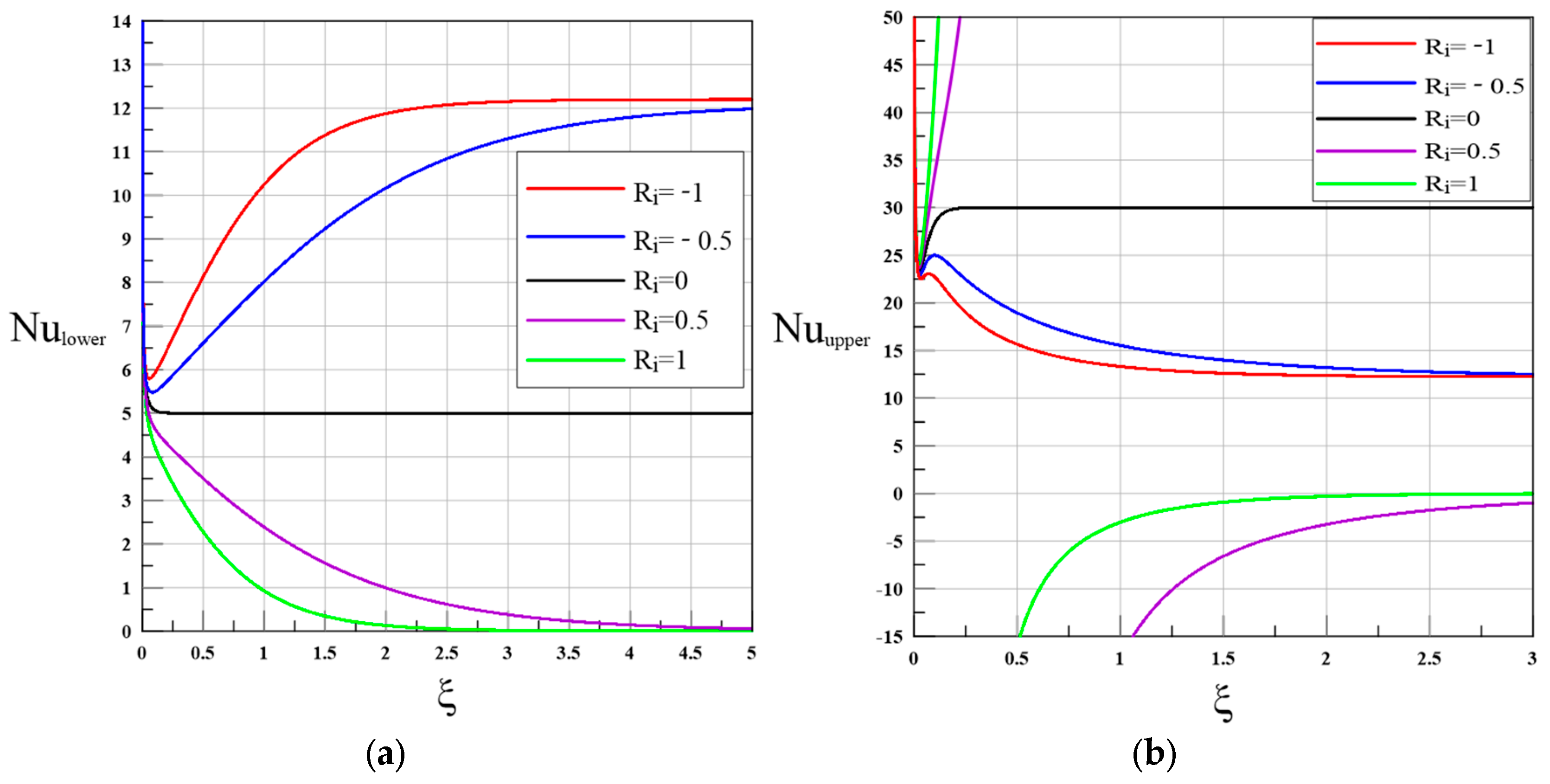

3.2. Flux–Flux Case

3.3. Implications for Climate Modeling and Sustainability

4. Conclusions

- ➢

- In isolated-flux conditions, stable stratification () thickens boundary layers and significantly reduces (by up to across the domain), inducing singularities from heat flux reversals.

- ➢

- Flux–flux cases show marked asymmetry under stratification: Stable stratification () delays development and suppresses mixing, driving toward zero. Conversely, unstable stratification () enhances vertical mixing, resulting in increasing markedly (by up to ) at the lower wall, while decreasing at the upper wall due to rapid homogenization.

- ➢

- These stem from buoyancy–inertia interactions, where stable reduces vertical motion, akin to oceanic thermoclines, while unstable drives strong, asymmetric convective transport.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Glossary

| Variables and Parameters | ||

| Symbol | Description | Units |

| specific heat | ||

| Gravitational acceleration | ||

| Channel height | ||

| Convective heat transfer coefficient | ||

| Thermal conductivity | ||

| Temperature | ||

| Characteristic temperature difference (e.g., | ||

| Velocity of the moving wall | ||

| Streamwise (axial) coordinate | ||

| Vertical (transverse) coordinate | ||

| Thermal diffusivity | ||

| Thermal expansion coefficient | ||

| Kinematic viscosity | ||

| Fluid density | ||

| Dimensionless Quantities | ||

| Symbol | Definition | Description |

| Dimensionless Vertical coordinate | Ranging from 0 (lower wall) to 1 (upper wall). | |

| Dimensionless Temperature | ||

| Dimensionless Streamwise coordinate | Used as the independent variable in the energy equation. | |

| : Péclet number | Ratio of advective to diffusive heat transport. | |

| Richardson number | Ratio of buoyancy forces to shear forces (the stratification parameter). | |

| : Nusselt number | Dimensionless heat transfer coefficient (ratio of convective to conductive heat transfer). | |

| Abbreviations | ||

| PINN | Physics-Informed Neural Network | |

| ABL | Atmospheric Boundary Layer | |

| GCM | Global Climate Model | |

| LES | Large-Eddy Simulation | |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goal | |

| RK4 | Fourth-order Runge–Kutta method | |

| DNS | Direct Numerical Simulation | |

| CO2 | Carbon Dioxide | |

| RCP | Representative Concentration Pathway (mentioned in the context of RCP8.5 in future directions) | |

References

- IPCC. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, L.; Li, G.; Long, S.M.; Li, Y.; von Schuckmann, K.; Trenberth, K.E.; Mann, M.E.; Abraham, J.; Du, Y.; Cheng, X.; et al. Ocean stratification in a warming climate. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 637–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deardorff, J.W. Numerical Study of Three-Dimensional Turbulent Channel Flow at Large Reynolds Numbers. J. Fluid Mech. 1970, 41, 453–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, S.B. Turbulent flows. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2001, 12, 2020–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, P.P.; McWilliams, J.C. Dynamics of Winds and Currents Coupled to Surface Waves. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 2010, 42, 19–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, T.; Teixeira, J.; Bretherton, C.; Brient, F.; Pressel, K.G.; Schär, C.; Siebesma, A.P. Climate Goals and Computing the Future of Clouds. Nat. Clim. Change 2017, 7, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monin, A.S.; Obukhov, A.M. Basic Laws of Turbulent Mixing in the Surface Layer of the Atmosphere. Tr. Geophiz. Inst. SSSR 1954, 24, 163–187. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, J.S. Buoyancy Effects in Fluids; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, J.W. On the Stability of Heterogeneous Shear Flows. J. Fluid Mech. 1961, 10, 496–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, L.N. Note on a Paper of John W. Miles. J. Fluid Mech. 1961, 10, 509–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugeat, B.; Boldini, P.C.; Hasan, A.M.; Pecnik, R. Instability in Strongly Stratified Plane Couette Flow with Application to Supercritical Fluids. J. Fluid Mech. 2024, 984, A31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michiyoshi, I.; Kikuchi, Y. Buoyancy Effects on Forced Convection Flow and Heat Transfer. Mem. Fac. Eng. Kyoto Univ. 1969, 31, 363–380. [Google Scholar]

- Madhusudanan, A.; Illingworth, S.J.; Marusic, I.; Chung, D. Navier-Stokes–based linear model for unstably stratified turbulent channel flows. Phys. Rev. Fluids 2020, 7, 044601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, H.; Basu, S.; Holtslag, A.A.M. Improving stable boundary-layer height estimation using a stability-dependent critical bulk Richardson number. Bound.-Layer Meteorol. 2013, 148, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Incropera, F.P. Buoyancy effects in double-diffusive and mixed convection flows. In International Heat Transfer Conference Digital Library; Begel House Inc.: Danbury, CT, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Townsend, A.A. Natural convection in the earth’s boundary layer. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 1962, 88, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornarelli, F.; Lippolis, A.; Oresta, P. Buoyancy Effect on the Flow Pattern and the Thermal Performance of an Array of Circular Cylinders. J. Heat Transf. 2017, 139, 022501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raissi, M.; Perdikaris, P.; Karniadakis, G.E. Physics-Informed Neural Networks: A Deep Learning Framework for Solving Forward and Inverse Problems Involving Nonlinear Partial Differential Equations. J. Comput. Phys. 2019, 378, 686–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karniadakis, G.E.; Kevrekidis, I.G.; Lu, L.; Perdikaris, P.; Wang, S.; Yang, L. Physics-Informed Machine Learning. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2021, 3, 422–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Yang, X. A physics-informed deep learning framework for estimating thermal stratification in a large deep reservoir. Water Resour. Res. 2025, 61, e2025WR040592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, L.; Manan, A.; Ali, B. Maxwell Nanofluids: FEM Simulation of the Effects of Suction/Injection on the Dynamics of Rotatory Fluid Subjected to Bioconvection, Lorentz, and Coriolis Forces. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Teng, Y.; Perdikaris, P. Understanding and Mitigating Gradient Flow Pathologies in Physics-Informed Neural Networks. SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 2021, 43, A3055–A3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengio, Y.; Louradour, J.; Collobert, R.; Weston, J. Curriculum Learning. In Proceedings of the 26th Annual International Conference on Machine Learning, Montreal, QC, Canada, 14–18 June 2009; Volume 41, pp. 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Raissi, M. Deep Hidden Physics Models: Deep Learning of Nonlinear Partial Differential Equations. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2018, 19, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Sun, C. Twin Forces: Similarity between Rotation and Stratification Effects on Wall Turbulence. J. Fluid Mech. 2024, 979, A45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebhart, B.; Jaluria, Y.; Mahajan, R.L.; Sammakia, B. Buoyancy-Induced Flows and Transport; Hemisphere Publishing Corporation: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

| Standard PINN | Proposed Deep PINN | |

|---|---|---|

| Configuration | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| −1.0 | Isolated-Flux | 0.008/0.021 | 0.006/0.018 | 0.004/0.012 |

| 0.0 | Isolated-Flux | 0.002/0.006 | 0.001/0.004 | 0.001/0.003 |

| +1.0 | Isolated-Flux | 0.009/0.023 | 0.007/0.019 | 0.005/0.013 |

| −1.0 | Flux–Flux | 0.007/0.019 | 0.005/0.015 | 0.003/0.010 |

| +1.0 | Flux–Flux | 0.008/0.020 | 0.006/0.017 | 0.004/0.011 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Haddout, Y.; Haddout, S. Deep Physics-Informed Neural Networks for Stratified Forced Convection Heat Transfer in Plane Couette Flow: Toward Sustainable Climate Projections in Atmospheric and Oceanic Boundary Layers. Fluids 2025, 10, 322. https://doi.org/10.3390/fluids10120322

Haddout Y, Haddout S. Deep Physics-Informed Neural Networks for Stratified Forced Convection Heat Transfer in Plane Couette Flow: Toward Sustainable Climate Projections in Atmospheric and Oceanic Boundary Layers. Fluids. 2025; 10(12):322. https://doi.org/10.3390/fluids10120322

Chicago/Turabian StyleHaddout, Youssef, and Soufiane Haddout. 2025. "Deep Physics-Informed Neural Networks for Stratified Forced Convection Heat Transfer in Plane Couette Flow: Toward Sustainable Climate Projections in Atmospheric and Oceanic Boundary Layers" Fluids 10, no. 12: 322. https://doi.org/10.3390/fluids10120322

APA StyleHaddout, Y., & Haddout, S. (2025). Deep Physics-Informed Neural Networks for Stratified Forced Convection Heat Transfer in Plane Couette Flow: Toward Sustainable Climate Projections in Atmospheric and Oceanic Boundary Layers. Fluids, 10(12), 322. https://doi.org/10.3390/fluids10120322