1. Introduction

Owing to escalating environmental concerns, the demand for clean energy solutions has seen a substantial rise [

1,

2,

3]. Hydrogen energy offers substantial promise in advancing the transition to a clean energy future and plays a crucial role in achieving deep decarbonization on a large scale. Water electrolysis represents a pivotal technology for green hydrogen production, offering a sustainable pathway to generate hydrogen while simultaneously mitigating the intermittency and variability inherent in renewable energy sources, thereby enhancing grid stability and energy storage capabilities [

4,

5]. Fuel cells, particularly PEMFC, have emerged as a promising technology in this shift. A fuel cell operates by reacting hydrogen with oxygen to form water and release heat, while the associated electrochemical process produces electrical power [

6]. Their low-temperature operation, fast start-up capabilities, and strong energy-conversion performance make these fuel cells attractive for portable power devices, transportation technologies, and various co- or multigeneration applications [

7]. Previous studies emphasize that the geometry of the flow channels within the bipolar plates is a crucial factor, as well-designed channels enhance mass transport and can substantially raise the achievable power density of PEMFC systems [

8].

Recognizing the significant influence of channel architecture on PEMFC performance, extensive numerical and experimental investigations have been devoted to examining both traditional channel configurations and emerging, non-conventional flow-path concepts. Many recent designs introduce internal features or adopt biomimetic structural ideas to lower pressure losses between the inlet and outlet passages, ultimately improving overall cell performance. Kumar and Reddy [

9] examined four distinct flow-field layouts serpentine, parallel, multi-parallel, and discontinuous under both steady-state and transient operating conditions. They found that the discontinuous configuration offered superior power density during steady operation, whereas parallel-type channels delivered better performance when the system underwent transient changes. Kuo and Chen [

10] proposed a wavy-shaped channel configuration that increased convective heat transfer, which in turn accelerated electrochemical reaction rates and improved cell output, particularly under high current density conditions. Drawing inspiration from the branching structure of the mammalian lung, Kloess et al. [

11] designed a biomimetic flow field that produced markedly more uniform gas distribution, as demonstrated through numerical simulation. Xiao et al. [

12] carried out numerical development of a PEMFC model inspired by the vein network of a tree leaf, providing theoretical justification for the optimization of such biomimetic flow-field architectures.

CFD has become an indispensable approach for investigating and optimizing the performance of PEMFCs. Numerical simulations provide detailed insights into local flow patterns, species transport, and electrochemical interactions that are often difficult to capture experimentally. Recent studies have demonstrated that CFD enables systematic evaluation of channel geometry, taper ratios, and operating conditions, offering predictive capabilities for fuel distribution, water management, and pressure loss estimation. This approach not only reduces experimental costs and development time but also provides valuable guidance for improving flow field design and enhancing overall system efficiency [

13,

14,

15].

Moreover, recent CFD investigations [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20] have demonstrated remarkable progress in predictive modeling and simulation accuracy. These developments further establish CFD as a crucial tool for analyzing complex thermo-fluid dynamics and optimizing advanced energy systems such as PEM fuel cells.

Several researchers have investigated the geometric effects on PEMFC performance. Karrar H. Fahim et al. [

21] emphasized that flow field geometry is critical in achieving uniform reactant distribution across the catalyst surface, thereby enhancing electrochemical reactions and overall fuel cell efficiency. Elena Carcadea et al. [

22] conducted CFD and experimental analyses of various serpentine flow field configurations. Their findings revealed that increasing the number of channels and reducing channel width, particularly in a 14-channel layout, led to improved water management and higher current density, especially at elevated loads.

Additional studies have explored global geometric variables such as parallel-serpentine designs, mesh configurations, and tubular channel structures. Leila Rostami et al. [

23] proposed a novel V-Ribbed flow field design that merges serpentine and parallel characteristics to enhance gas distribution and reduce pressure drop. Their CFD results showed improved oxygen transport, reduced liquid water accumulation, and up to a 41.5% increase in current density compared to traditional designs. Similarly, Feng Sun et al. [

24] developed a 3D fine-mesh flow field model and demonstrated that increasing the porosity of the structure enhanced oxygen availability and reduced pressure losses, resulting in a 21.5% increase in peak power density over conventional parallel designs. Lastly, Lei Yuan et al. [

25] investigated tubular PEMFC with different flow arrangements and found that counter-flow configurations, particularly the square chordal design, significantly improved reactant uniformity and net power output.

Numerous investigators have demonstrated that the shape of the flow path and cross-section in PEMFC channels plays a crucial role in enhancing cell performance. Elaibi et al. [

26] investigates the impact of novel mixed cross-sectional flow-channel designs on fuel cell performance. The study concludes that these designs improve efficiency, reliability, and contribute to advancing clean energy technologies. Similarly, Wang et al. [

27] developed a variable cross-section wavy flow channel for PEM fuel cells to enhance mass transfer and water removal efficiency. Their CFD simulations identified optimal geometric parameters that improved current density by 9.06% compared to conventional designs.

Mahmut Kaplan et al. [

28] developed a 3D model showing that reducing channel width and depth significantly enhances current density (up to 57%) due to increased gas velocity, though at the cost of higher pressure drop. Keke Liu et al. [

8] proposed dome-like and branched variable cross-section channels, with CN-19 achieving the best performance, increasing current and power densities by enhancing oxygen distribution and flow. Chakrit Suvanjumrat et al. [

29] used a 3D multiphase CFD model to find that a channel aspect ratio of 1.0 maximizes power density, balancing pressure drop and transport efficiency. Yi Wu et al. [

30] compared five channel shapes rectangular, triangular, trapezoidal, inverted trapezoidal, and elliptical and reported that the triangular channel achieved the best performance in high-temperature PEMFCs by enhancing reactant utilization and gas permeation.

While existing research has explored either tapered channels (to accelerate flow and compensate for reactant depletion) or V-shaped cross-sections (to enhance under-rib convection), these approaches are often treated in isolation. The critical research gap lies in creating a synergistic design that effectively integrates both strategies. This study introduces the novel SVTC, an architecture specifically engineered to address this challenge. The SVTC is a multifunctional design. Its angled “V” walls are configured to promote under-rib convection, while its progressive symmetric tapering is designed to simultaneously accelerate flow, maintaining high reactant concentration and optimizing mass transport along the entire channel. This work moves beyond simple geometric comparisons to investigate the specific influence of these combined design parameters. By evaluating multiple SVTC configurations against traditional rectangular channels, this study demonstrates a new, integrated approach to flow field design, proving that the synergy of these features leads to significant enhancements in power density and vapor water management.

2. Numerical Method and Model Setup

2.1. Geometric Configuration

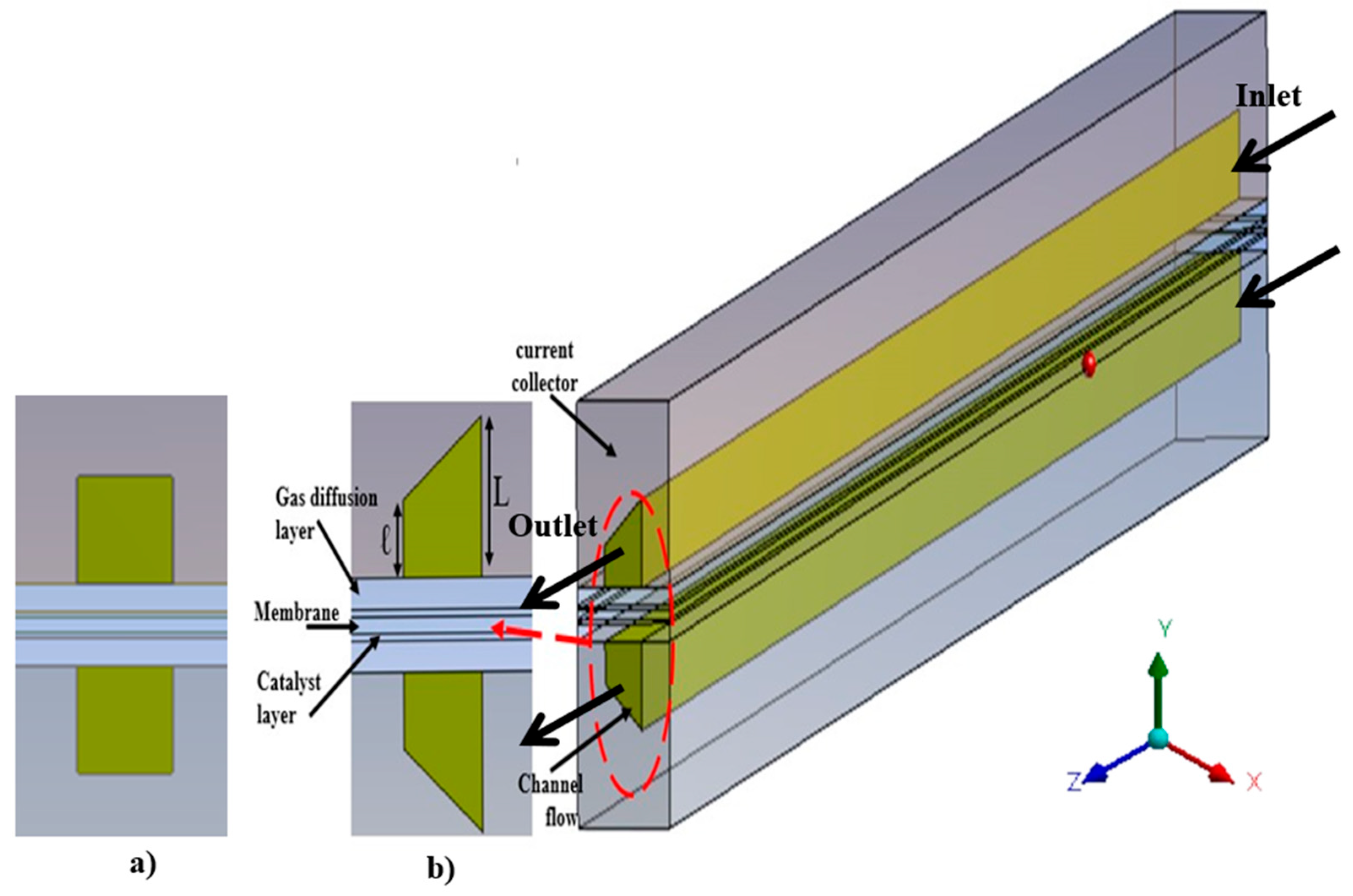

This study investigates a single-channel PEMFC with straight gas channels and a planar flow field design. The geometrical models of the selected PEMFC configurations were developed using ANSYS Design Modeler, as illustrated in

Figure 1a,b.

The cell structure consists of a current collector, a gas flow channel, a gas diffusion layer (GDL), and a catalyst layer (CL) on both the anode and cathode sides. A membrane is centrally positioned between these layers, forming a complete layered assembly. The detailed dimensions of each component are presented in

Table 1.

For the SVTC design, the trapezoidal channel section is characterized by lower and upper base lengths, denoted as ℓ and L, respectively, where ℓ < L, as shown in

Figure 1b. The ratio R = ℓ/L is introduced as a key geometric design parameter and is systematically varied to assess and optimize cell performance, as shown in

Table 2.

The simulation is conducted based on the following set of assumptions:

The model operates under steady-state and non-isothermal conditions.

Fluid flow is assumed to be laminar and incompressible.

The GDL, CL, and membrane are modeled as isotropic and homogeneous porous media.

Reactive gases follow ideal gas behavior.

Liquid water formation is neglected, and only water vapor transport is considered.

2.2. Modeling and Simulation Approach

In this study, two channel cross-sectional geometries SVTC and rectangular were analyzed using the ANSYS FLUENT 18.1 [

31] CFD software, as illustrated in

Figure 1. The symmetric V-tapered channel, characterized by a straight main path with opposing angled indentations forming a “V” shape on both the upper and lower walls, is designed to enhance local turbulence and improve reactant distribution across the flow field.

Numerical simulations are employed to evaluate how these channel configurations affect the fuel cell’s performance, pressure distribution, and transport phenomena within the PEMFC. The three-dimensional simulation framework integrates the Navier–Stokes equations for fluid flow, along with governing equations for energy and mass conservation, species transport, electrical charge conservation, and electrochemical kinetics described by the Butler-Volmer equation. The formulation and implementation of the coupled physical models follow the methodologies provided in the ANSYS PEMFC Add-on Module [

27,

28].

Variables u, v, and w denote the velocity components along the x, y, and z axes, respectively.

In this formulation, the symbol μ represents the dynamic viscosity of the gas phase, while , , and denote the directional permeability components in the x, y, and z directions, respectively, for both the CL and GDL.

Energy Transport

The conservation of energy is described by:

While a fuel cell’s maximum theoretical voltage is defined by its thermodynamic equilibrium potential (E), the actual operating voltage is always lower due to irreversible losses that occur when current is drawn. The usable cell potential (V

cell) is therefore determined by deducting the sum of all voltage losses, or overpotentials, from this ideal potential, as given by the following relationship [

26]:

The activation overpotential, denoted as

ηa,

c[

V] are determined from the local electrical potentials in the electrodes and membrane [

27]:

where

ηohm represents the ohmic losses. The parameter

Vcat corresponds to the cathode half-cell potential, which serves as a model input to establish the operating condition of the fuel cell. The reversible cell potential

E in Equation (11) is obtained from the Nernst equation [

23]:

The ohmic losses in Equation (11) are computed by solving the potential distribution equations within the gas diffusion layers.

The polymer electrolyte membrane plays a key role in understanding water transport behavior within fuel cells. Inside the membrane, water moves through two main mechanisms electro-osmotic drag and diffusion both of which are governed by the membrane’s hydration level. The corresponding protonic conductivity, σ, is determined using the empirical relation provided in Refs. [

27,

29]:

The above empirical expression for membrane protonic conductivity follows the correlation proposed by Springer et al. [

32] for Nafion 117 membranes. In this relation, λ is the number of water molecules per sulfonic acid group (dimensionless) and T is the absolute temperature (K). The constants were empirically adjusted to yield conductivity in ohm

−1 m

−1, ensuring full dimensional consistency. This formulation remains the standard model for describing the coupled influence of temperature and hydration on proton transport in polymer electrolyte membranes.

2.3. Boundary Conditions

All simulations maintained constant flow rates at the channel inlets, consistent with the specified anode and cathode humidification levels, using air as the oxidant. Dirichlet boundary conditions were imposed on species concentration, heat, and mass flow at the anode and cathode inlets, while the outlets were governed by a specified pressure. The external surfaces of the fuel cell were treated with Neumann boundary conditions to ensure zero flux and adiabatic walls. The transport equations for species, momentum, energy, mass, electric charges, and electrochemical kinetics were solved using the software’s integrated algorithm. To ensure numerical stability, relaxation coefficients of 0.95 were applied to the species, water content, and energy equations, with coefficients of 0.3 and 0.7 used for momentum and pressure, respectively. The solver utilized F-cycle Multigrid cycles (Full Approximation Scheme) to accelerate convergence, and the BICGSTAB method (Biconjugate Gradient Stabilize Method) was employed to stabilize the iterative solutions for species concentrations, water saturation, and electrical potentials. The cell’s performance was evaluated by constructing a polarization (I–V) curve from 160 steady-state simulations, sweeping the voltage from an open circuit condition down to 0.15 V.

2.4. Mesh Independence

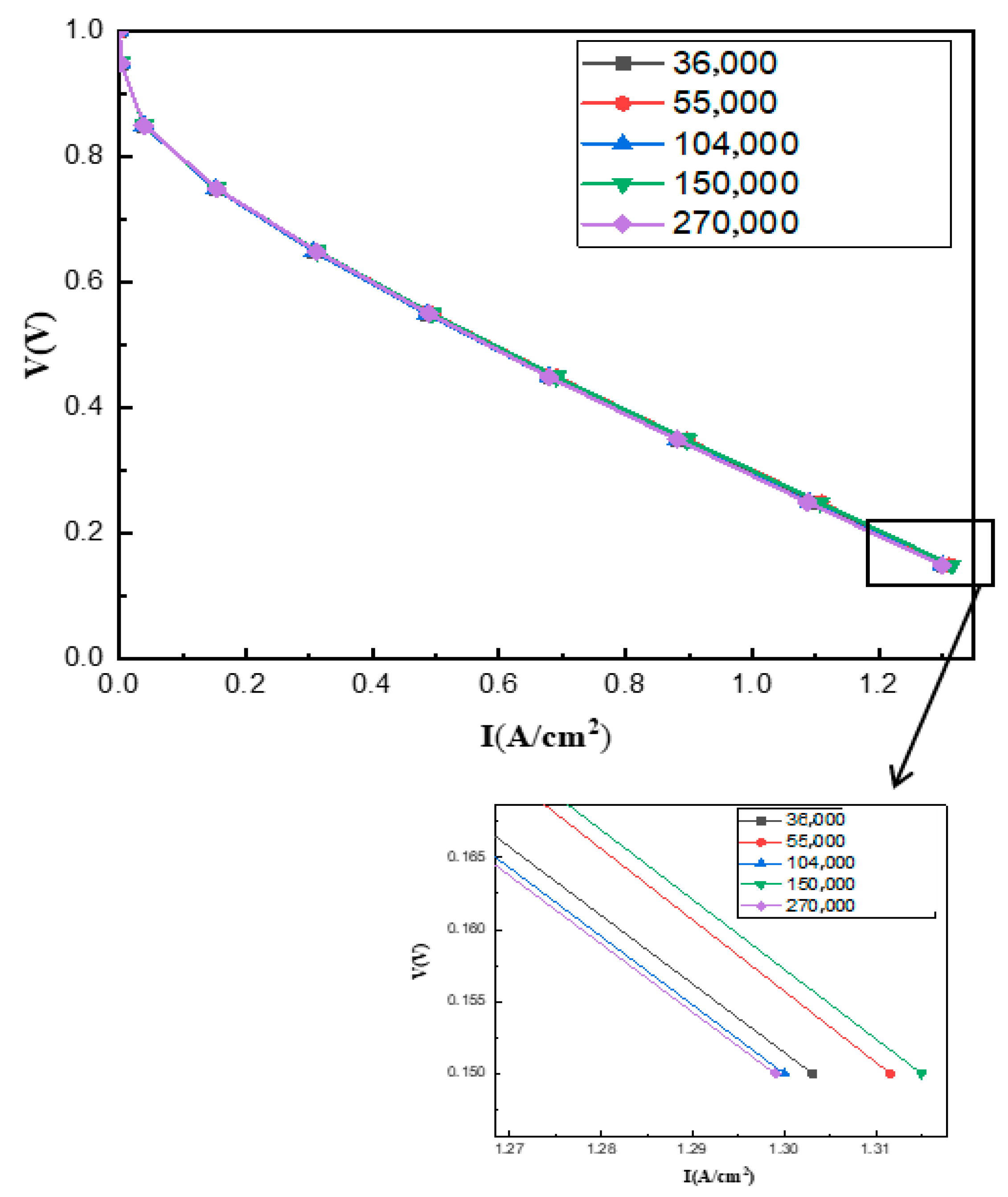

A mesh independence study was conducted to evaluate the numerical uncertainty associated with the spatial discretization in the CFD model. Using ANSYS Mesh, five distinct non-uniform grids were generated, refined in the x- and y-directions while maintaining a uniform structure in the z-direction.

The resulting polarization curves for all five cases, shown in

Figure 2, demonstrated very close agreement. The mesh comprising 36,000 elements was selected for all subsequent simulations, as its I-V curve occupied a central position among the tested cases, confirming its representativeness. This configuration offers an optimal balance, being the smallest mesh that substantially reduces computational expense without compromising result accuracy.

The finalized mesh structure featured 80 divisions along the Z-axis, 10 along the x-axis, and a y-axis distribution of five divisions each for the CL, GDL, and membrane, 10 for the current collector, and five for the channel.

2.5. Validation

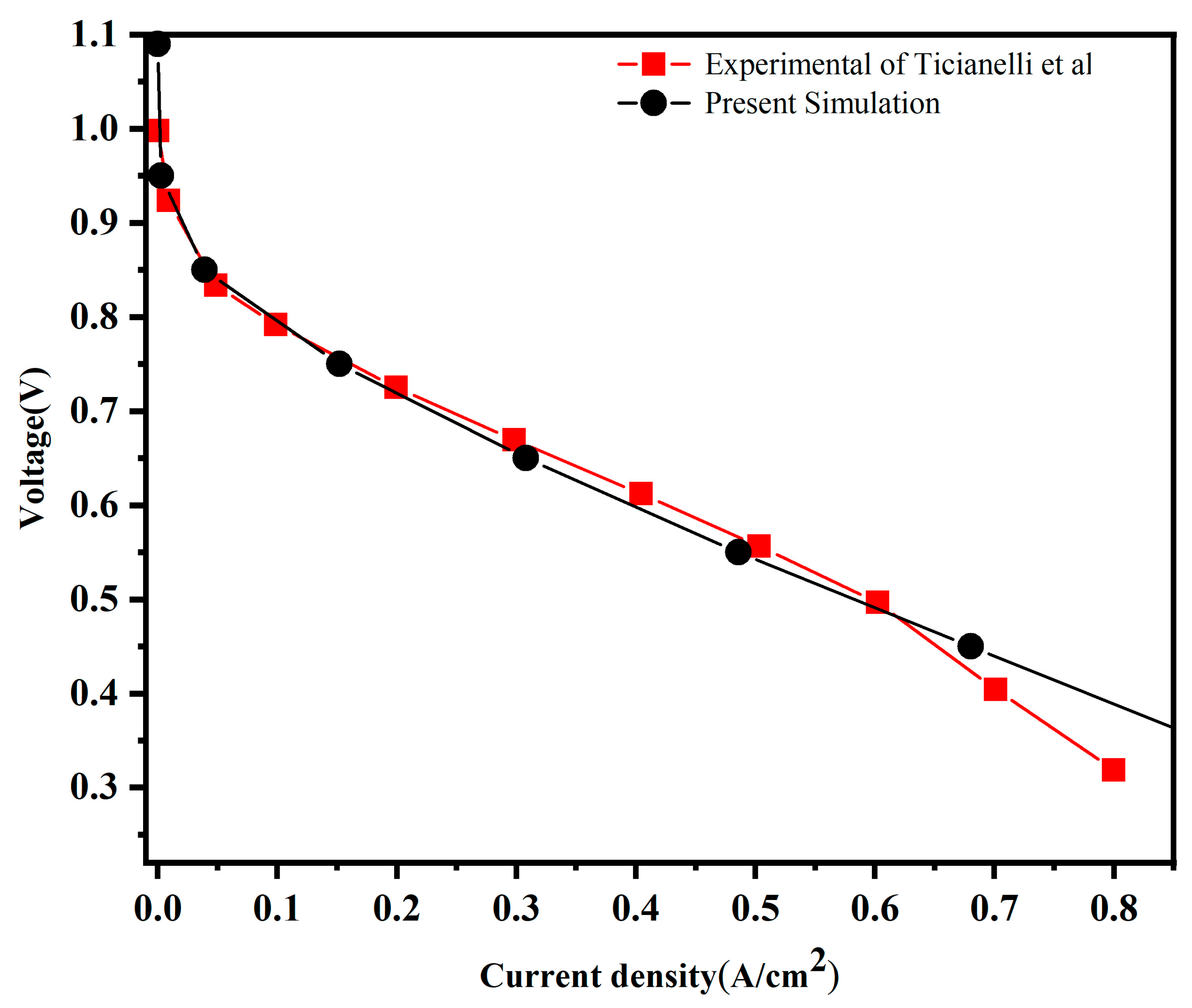

The accuracy of the computational model was verified by comparing the simulated polarization curve with published experimental results from Ticianelli et al. [

33], as presented in

Figure 3.

The model demonstrates excellent agreement with the experimental results in the low current density region, confirming its predictive accuracy under these conditions. A minor deviation emerges at higher current densities, where the simulated voltage slightly overpredicts the experimental values. This discrepancy is likely due to factors such as mass transport overpotentials, inherent model simplifications, or unaccounted thermal effects that become more pronounced at high loads.

Nevertheless, with a mean absolute percentage error of 6% across the operating range, the validation confirms that the simulation robustly captures the overall performance characteristics of the PEMFC, affirming its suitability for the present study.

3. Results and Discussion

After developing and simulating a PEMFC single-cell base model featuring straight channels in the commercial CFD software ANSYS FLUENT 18.1 [

31], Our earlier studies [

34,

35] comprehensively address the mesh independence test and offer a detailed comparison between numerical simulations and experimental data. While these referenced articles contain extensive information and analysis, this study also includes a validation figure for completeness.

Two comparison strategies are employed in this study to evaluate the influence of channel geometry on fuel cell performance:

Shape-based comparison: The first strategy involves comparing a conventional rectangular channel (with dimensions ℓ = L = 0.8 mm) to the proposed SVTC geometry. In this case, both the cross-sectional area and the channel height are kept constant, allowing a direct assessment of the impact of geometry shape alone.

Taper ratio-based comparison: The second strategy uses a tapered reference channel Here, the taper ratio R = ℓ/L is systematically varied. To ensure a fair comparison, the cross-sectional area is held constant by adjusting the channel length L according to changes in ℓ. This method isolates the effect of tapering from variations in the inlet area, enabling a more precise evaluation of taper geometry on performance.

3.1. Effect of Cross-Section Geometry

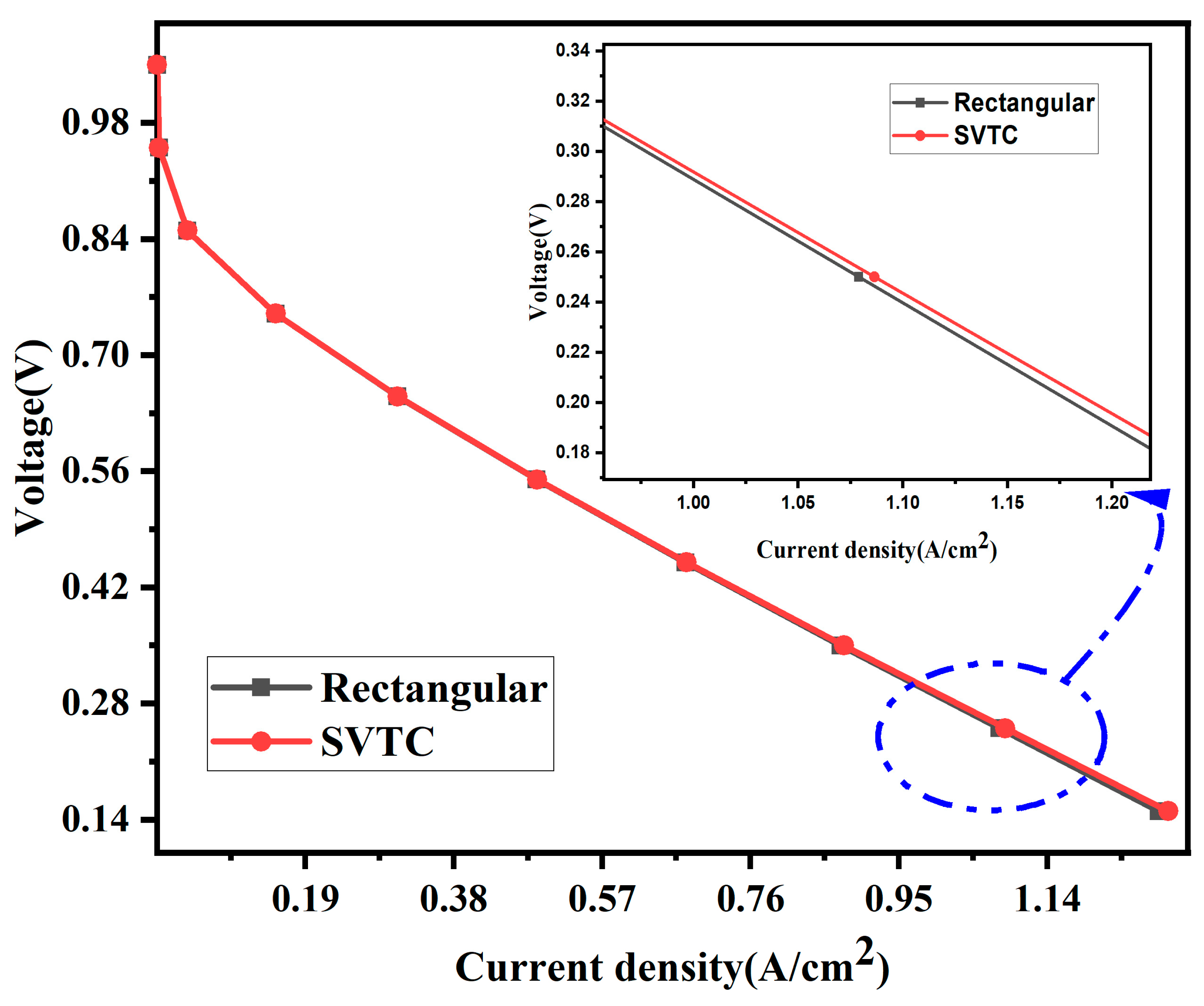

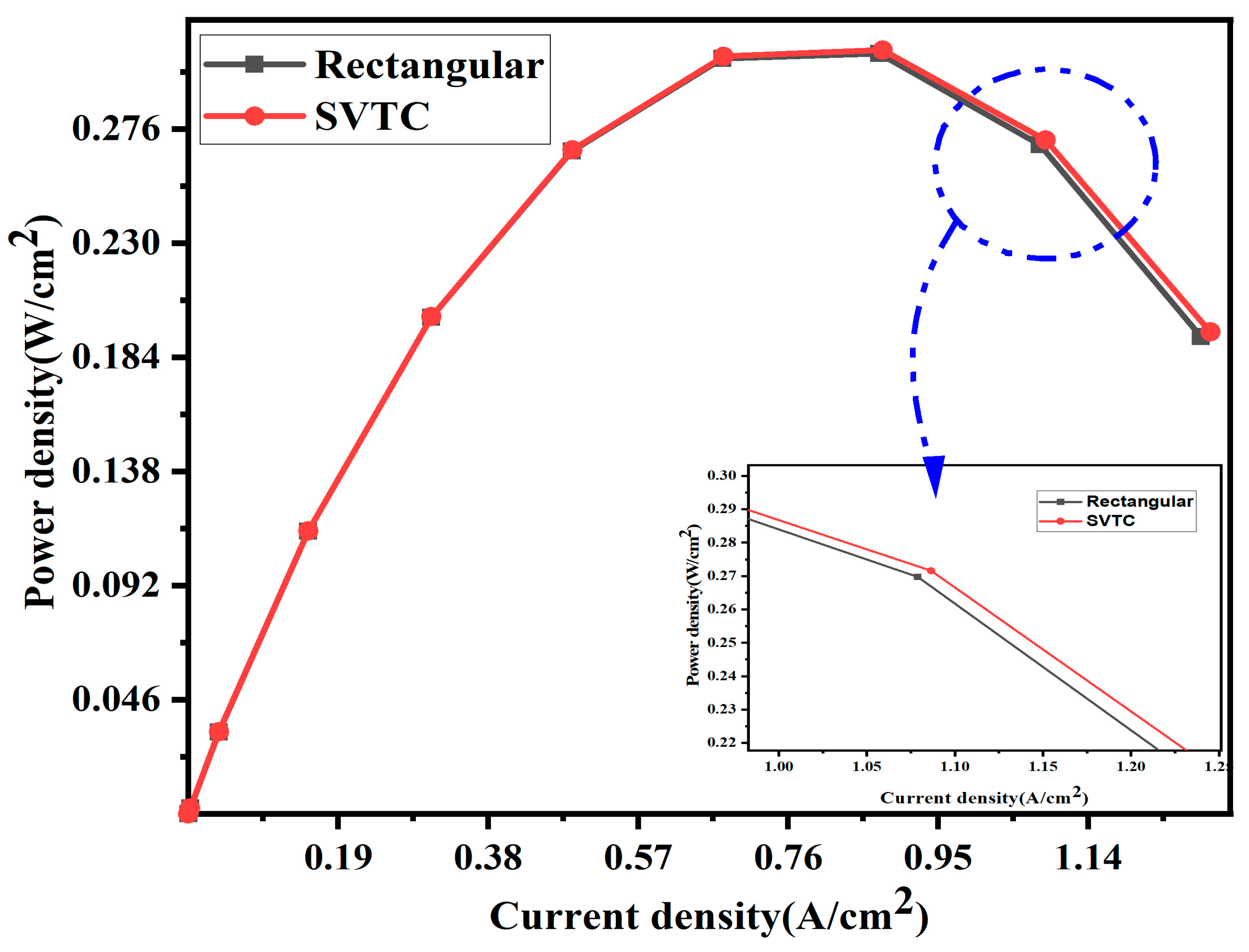

The results presented in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 clearly demonstrate the superior performance of the SVTC design compared to the rectangular channel configuration in a PEMFC.

An analysis of the polarization curves in

Figure 4 reveals enhanced voltage stability in the SVTC channel configuration relative to the conventional rectangular design. The SVTC maintains a higher voltage at elevated current densities, suggesting a reduction in both activation and ohmic losses. At a cell voltage of 0.35 V, the rectangular channel delivers a current density of 0.8755 A/cm

2, whereas the SVTC reaches 0.8796 A/cm

2. This improvement is attributed to more effective reactant transport and enhanced electrochemical activity within the flow field.

As shown in

Figure 5, the comparison of power density curves clearly demonstrates the superior performance of the SVTC channel configuration compared to the conventional rectangular design. The SVTC achieves a higher peak power output, suggesting more efficient fuel utilization and enhanced water and gas management within the flow field. At a cell voltage of 0.35 V, the rectangular channel produces a power density of 0.306425 W/cm

2, whereas the SVTC yields 0.30786 W/cm

2. Although the difference is modest, the consistent improvement underscores the influence of channel geometry on overall output efficiency.

These findings affirm that structural optimization particularly in channel geometry plays a pivotal role in enhancing fuel cell performance and improving overall operational efficiency.

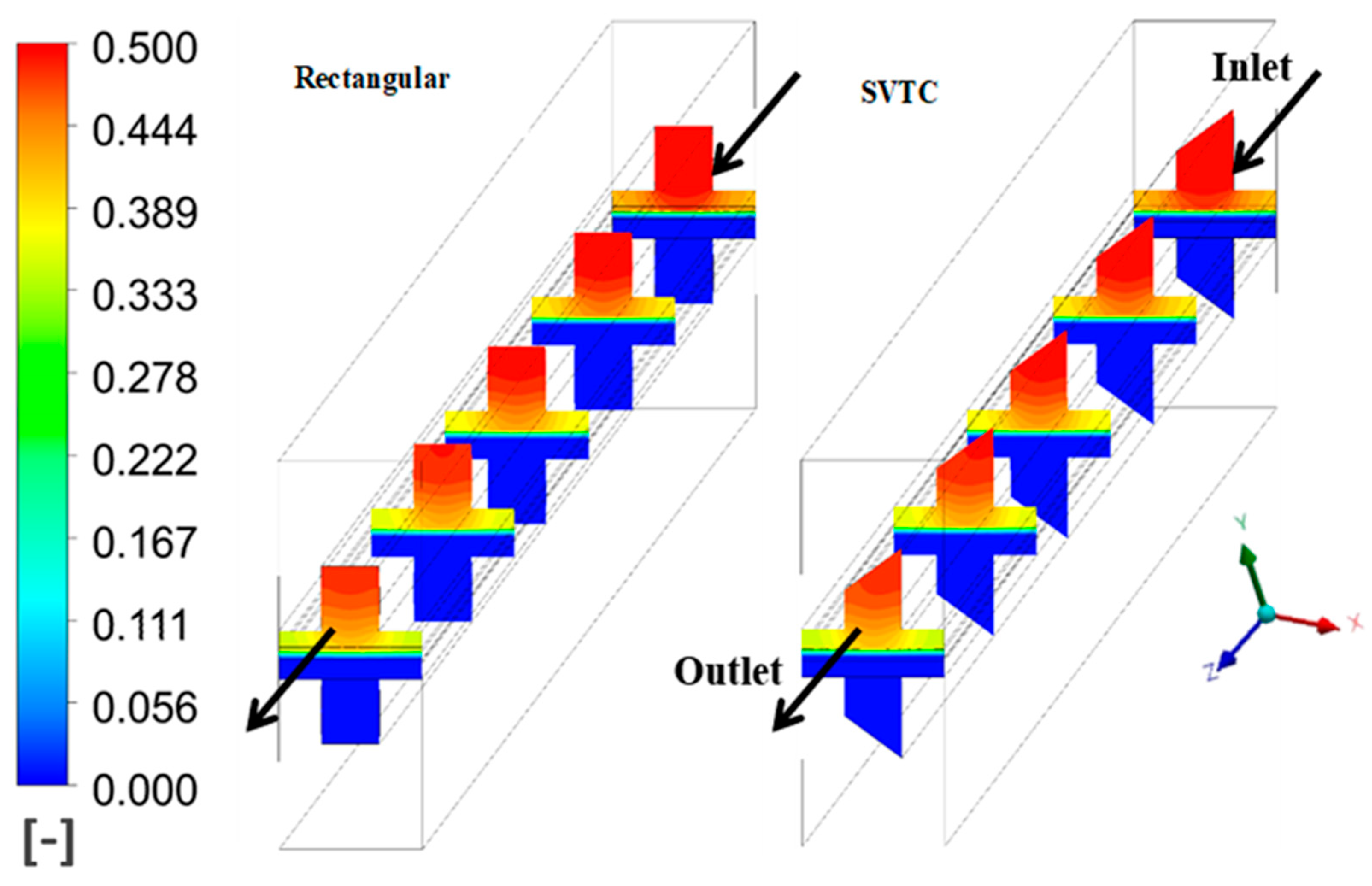

Figure 6 shows the hydrogen mass fraction distribution in the anode channels. The SVTC design exhibits a uniform hydrogen distribution throughout the flow field, unlike the rectangular channel, which shows significant depletion near the outlet regions. Such fuel starvation zones in the rectangular design directly contribute to the drop in voltage seen in

Figure 4.

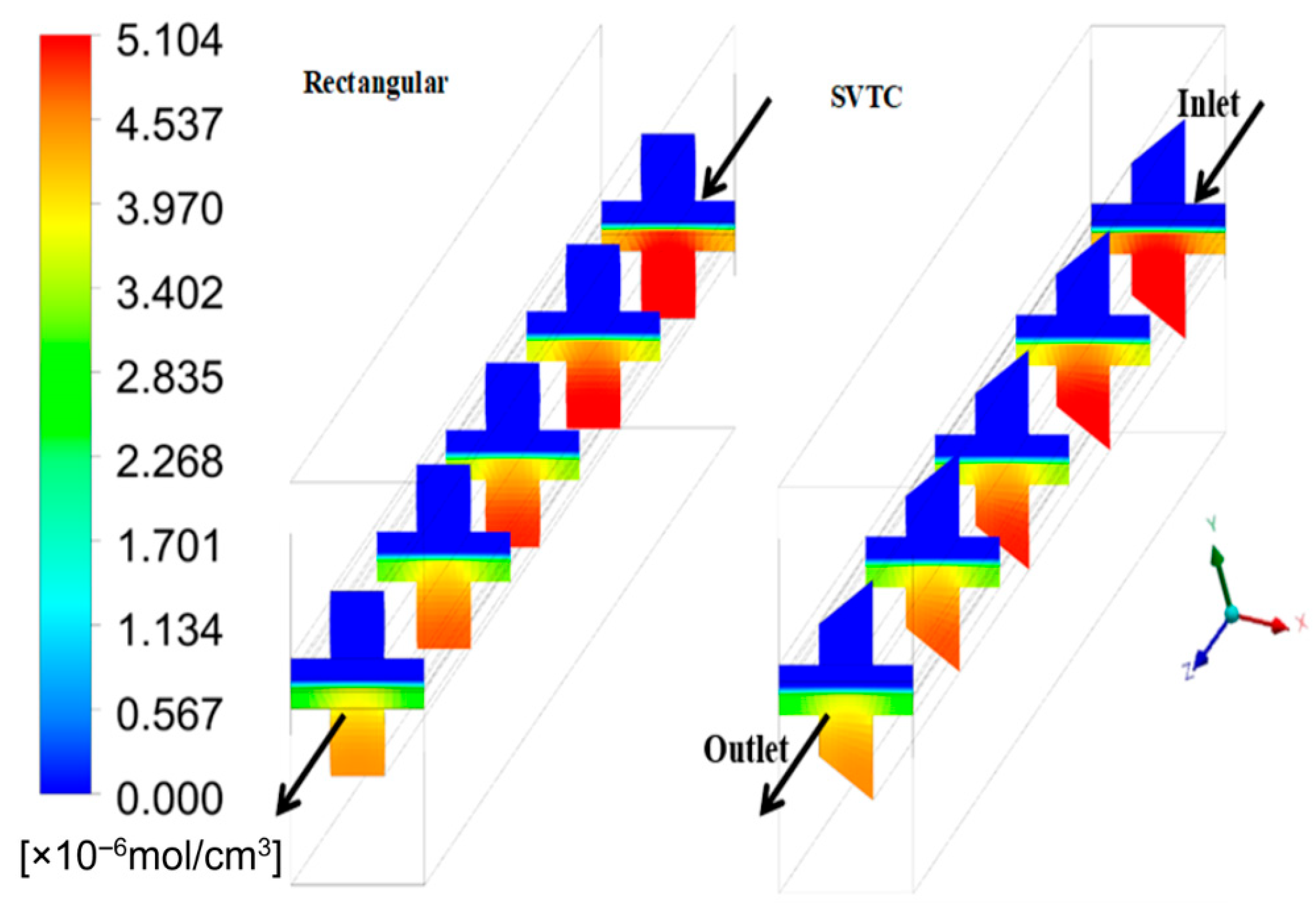

Figure 7 presents the oxygen molar concentration in the cathode channels. In the SVTC configuration, oxygen is more evenly distributed, enabling efficient reduction reactions across the active surface area. In contrast, the rectangular design exhibits oxygen starvation regions, especially at the downstream ends, leading to reduced reaction rates and a more pronounced voltage loss at higher current densities.

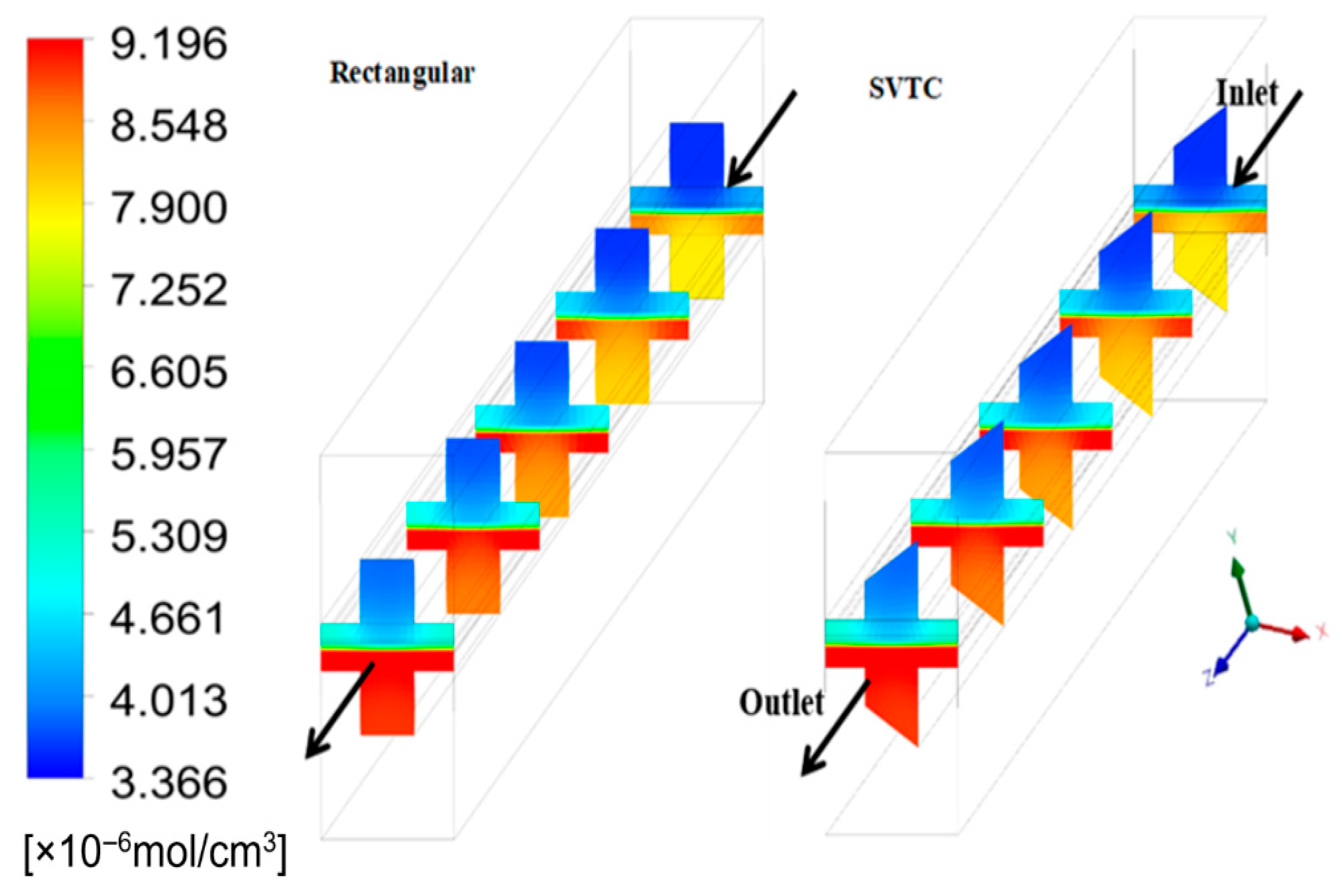

Figure 8 displays the water molar concentration within the cell. The SVTC design ensures effective water removal, avoiding accumulation and flooding that can block reactant access. Meanwhile, the rectangular design is prone to water buildup, especially in low-velocity corners, which increases mass transport limitations and negatively affects power output as seen in

Figure 5.

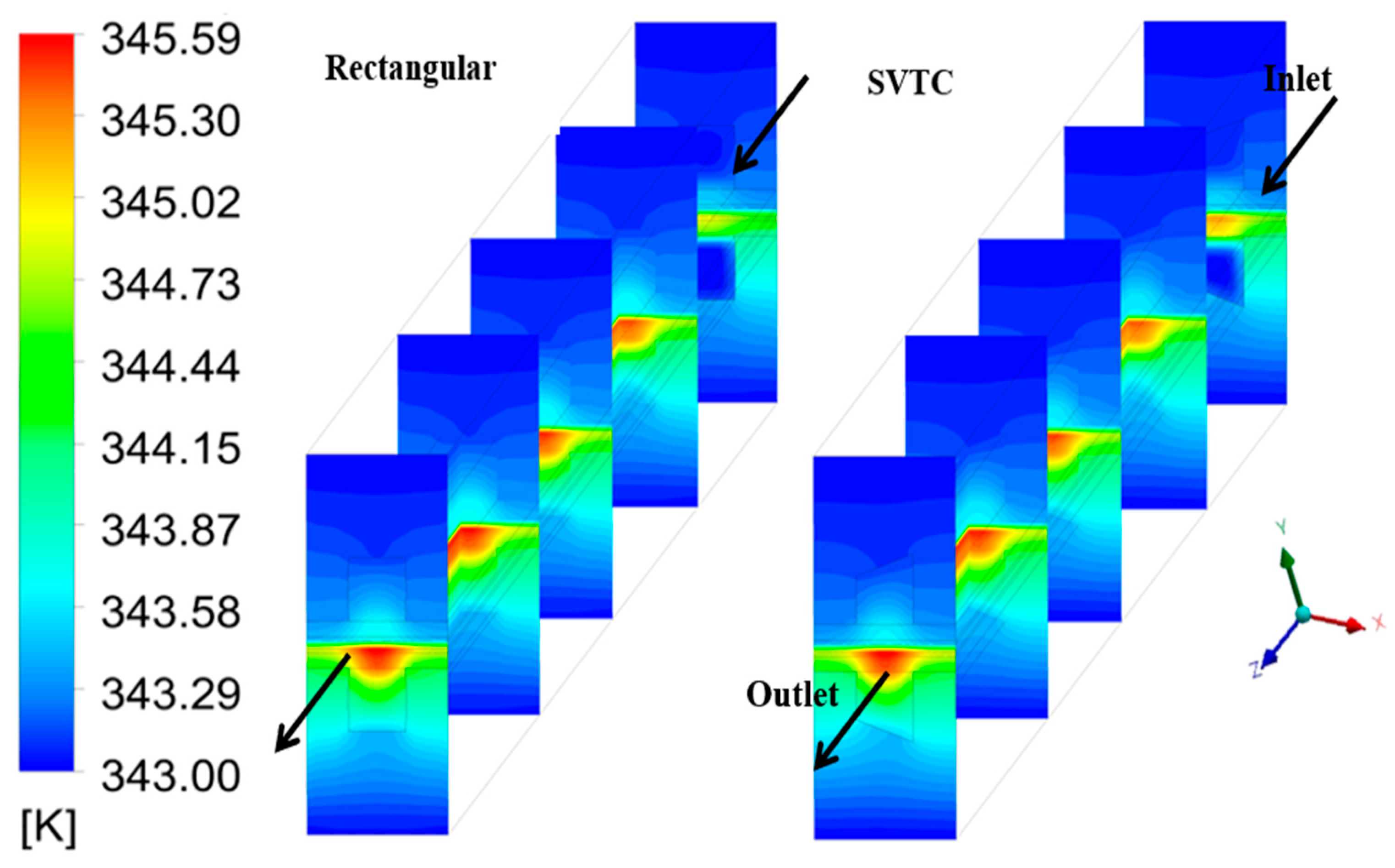

Figure 9 displays the temperature distribution within the PEMFC for rectangular and SVTC designs. The SVTC configuration shows slightly higher temperature values, particularly near the outlet, due to enhanced electrochemical reactions and improved reactant diffusion along the tapered sidewalls. This moderate temperature rise promotes better proton conductivity and more uniform heat distribution, while the rectangular design exhibits cooler zones caused by uneven reactant transport and localized reaction intensity.

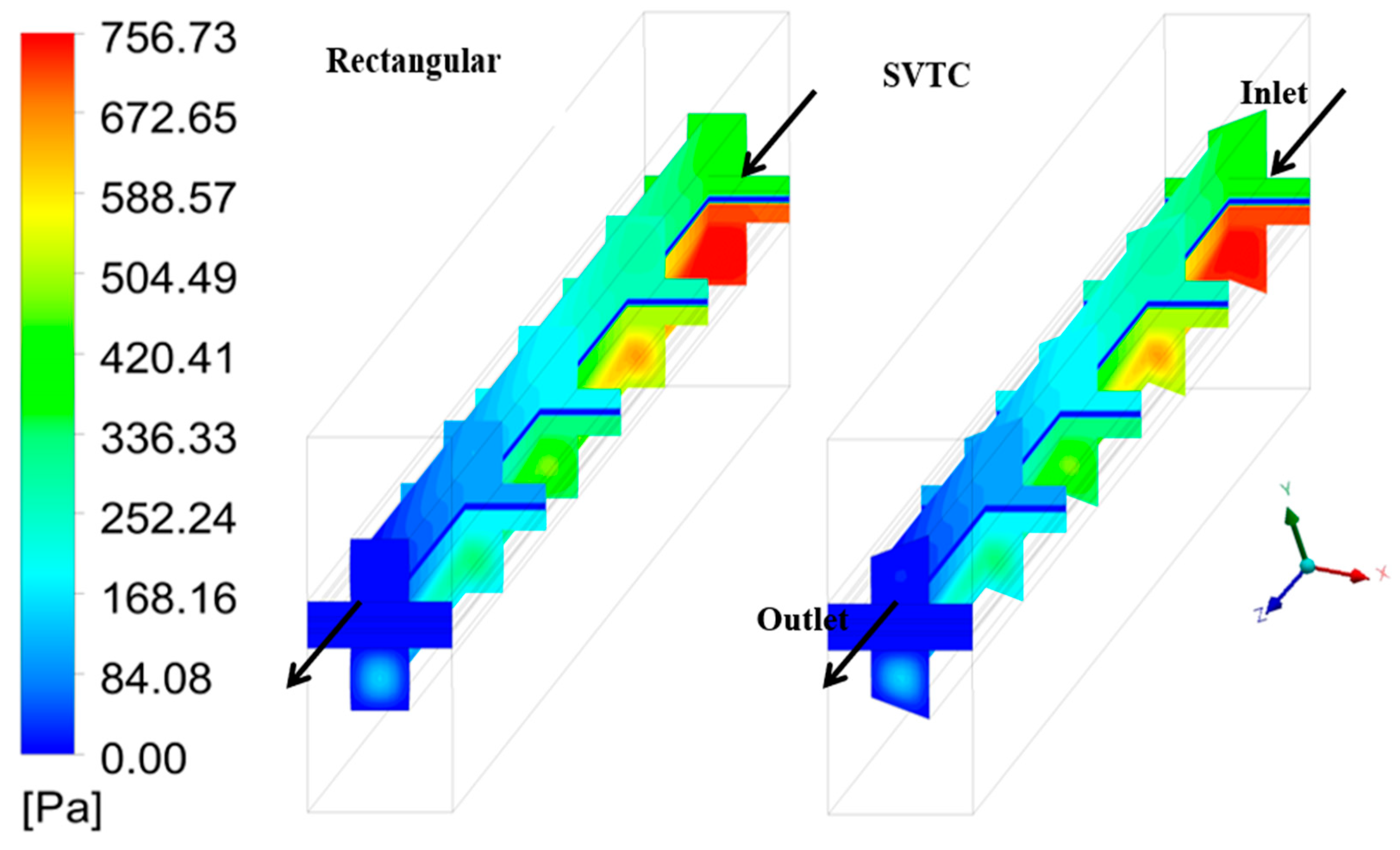

Figure 10 displays the pressure distribution within the PEMFC for rectangular and SVTC designs. The SVTC configuration produces a slightly higher pressure drop due to the tapered sidewalls, which accelerate gas flow and improve reactant convection along the channel. This promotes more uniform gas distribution and effective water removal, while the rectangular channel shows lower flow momentum and less efficient mass transfer.

3.2. Analysis of Polarization, Power Density, and Pressure Drop

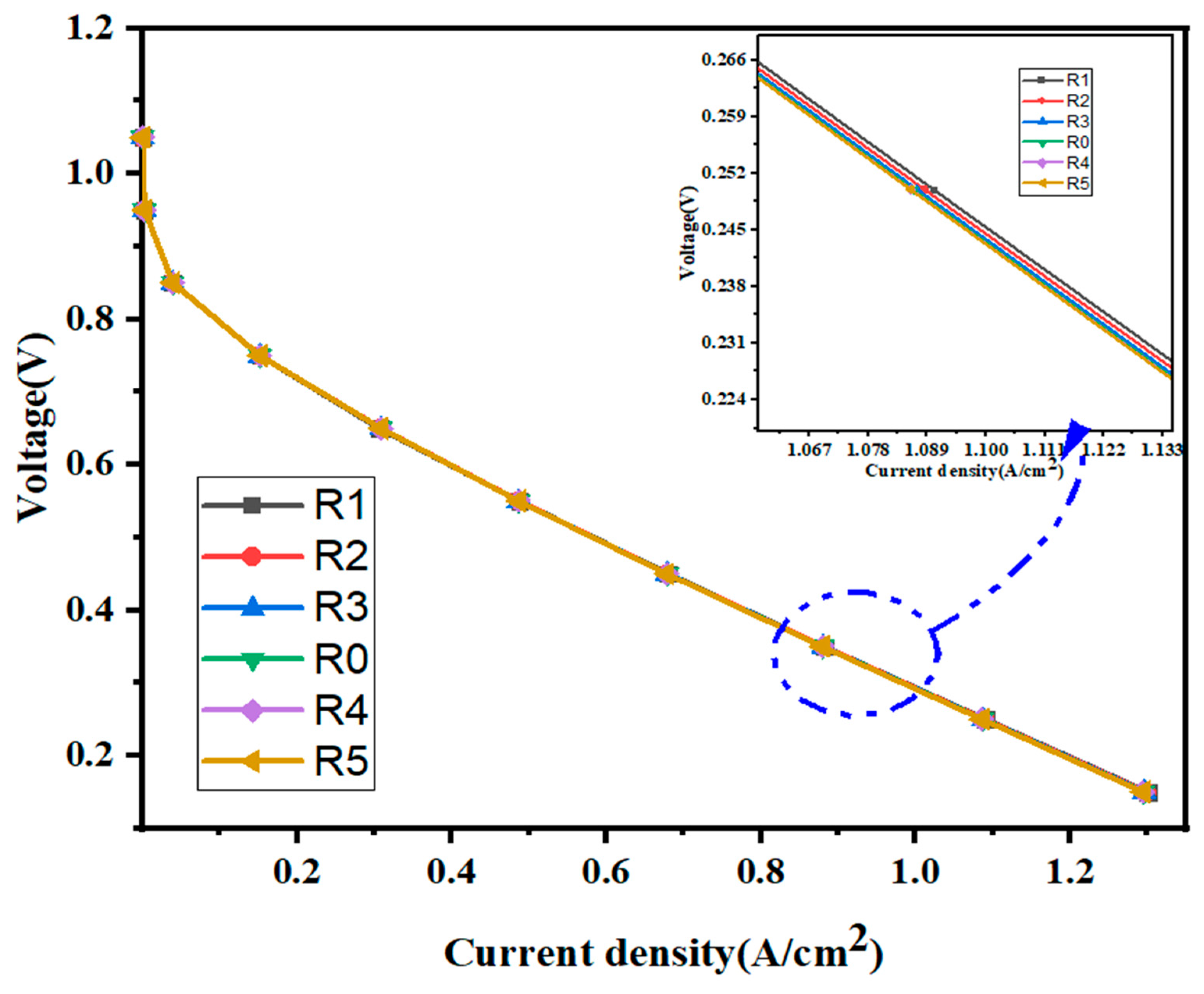

Figure 11 shows that all SVTC channel configurations exhibit a similar voltage current density trend, with voltage rising to a peak before declining. Peak performance occurs near 0.88 A/cm

2, where configuration R1 reaches 0.8822 A/cm

2 and R5 records 0.8794 A/cm

2. Although R5 has a slightly lower current density, it demonstrates better electrochemical performance. This improvement is likely attributed to enhanced reactant distribution, lower mass transport resistance, and more effective water removal resulting from the SVTC channel geometry.

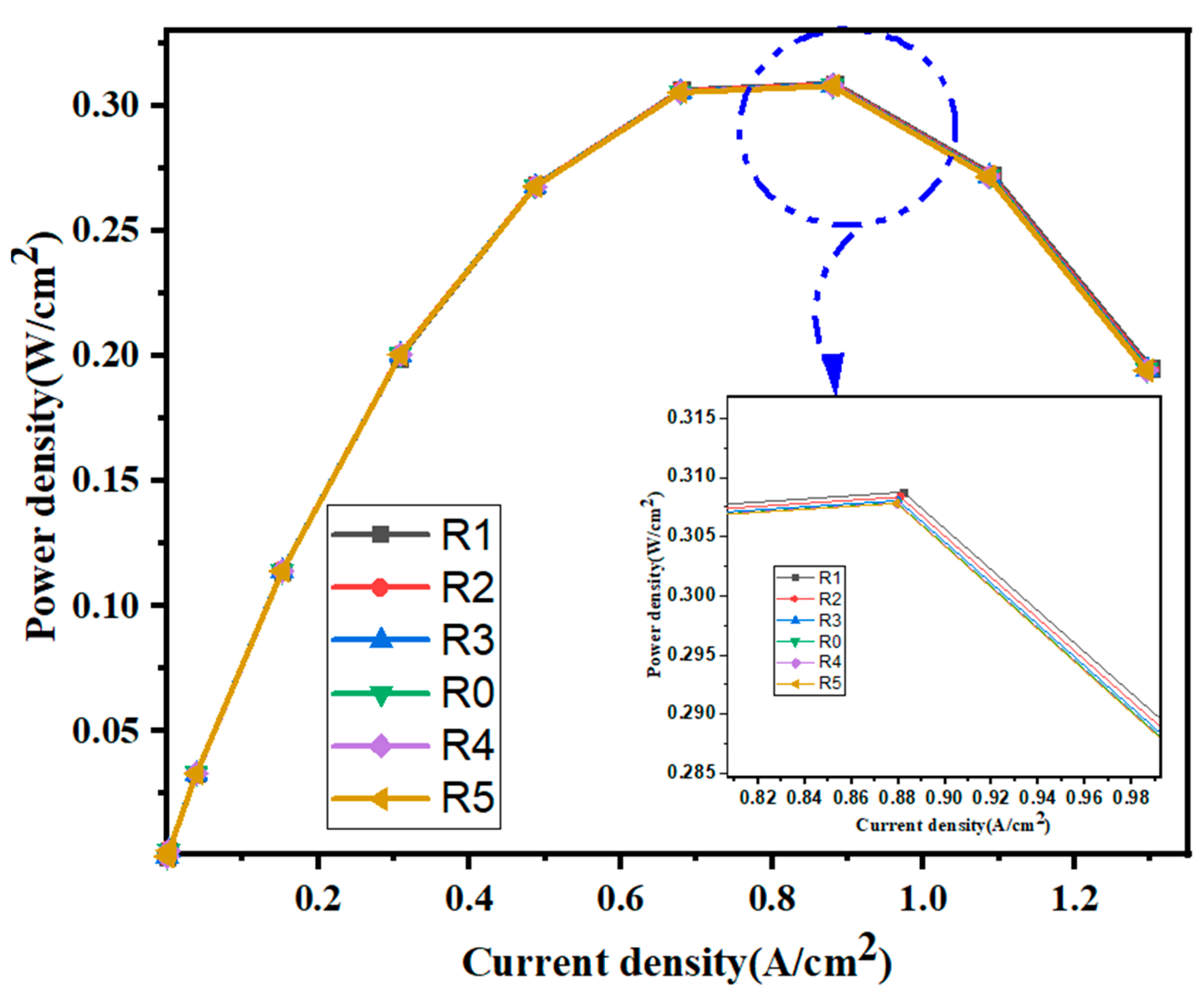

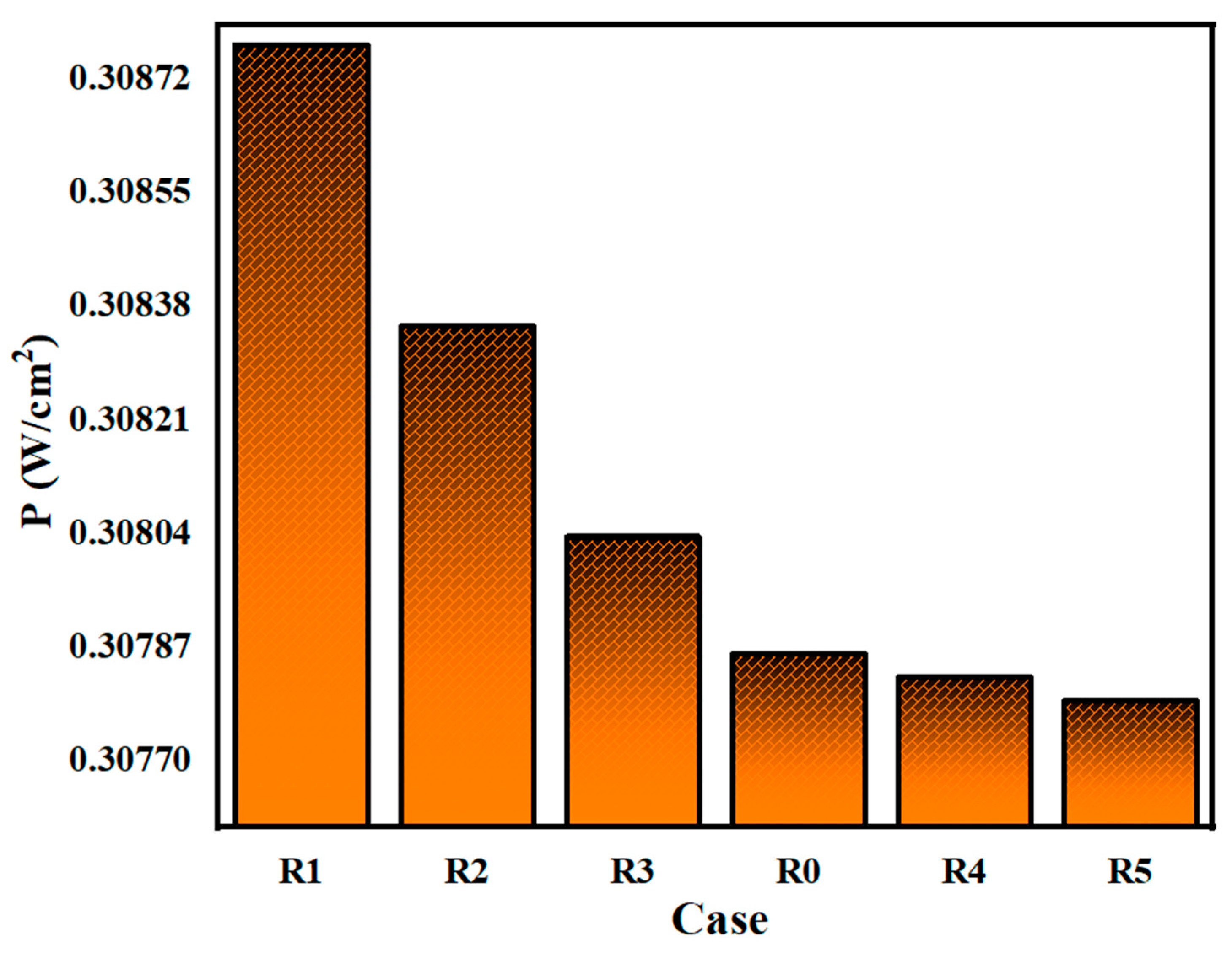

Figure 12 presents the power density characteristics for SVTC channel configurations with varying taper ratios. All designs exhibit a similar pattern, where power density increases with current density until reaching a maximum. Configuration R1 records the highest peak power density at 0.30877 W/cm

2, indicating the most efficient performance among the tested designs. R5 follows closely with a peak of 0.30779 W/cm

2. Despite the small difference, R5’s result highlights the beneficial influence of tapering in improving flow distribution, reducing transport losses, and enhancing water removal.

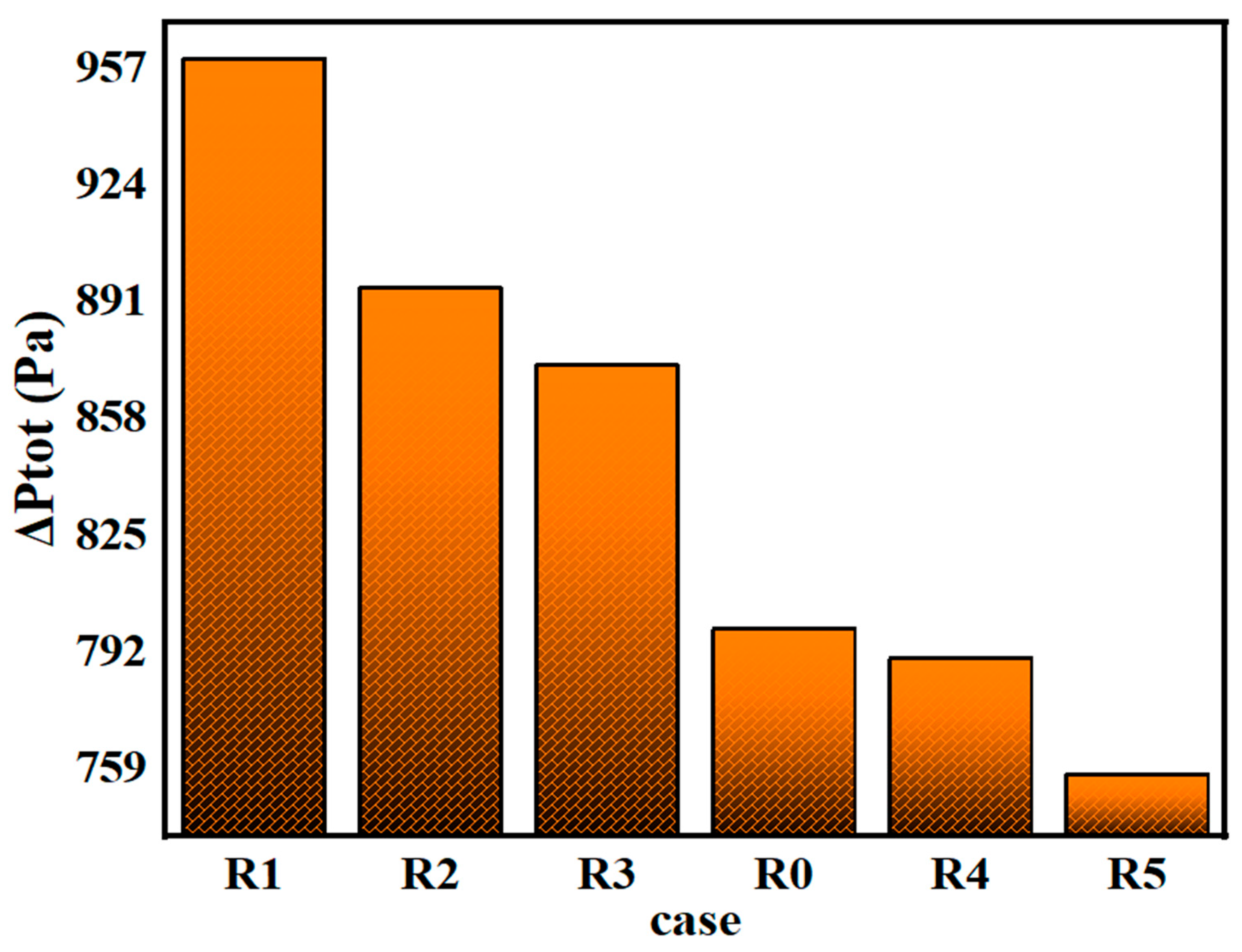

Figure 13 and

Figure 14 present the effect of taper ratio on output power density and total pressure drop in SVTC channels. As illustrated in

Figure 13, the output power density shows only slight variation across all configurations, ranging between 0.30779 and 0.30877 W/cm

2. These minor differences indicate that tapering exerts little influence on the gross electrochemical output of the system.

It is important to note that the total pressure drop is computed as the difference between the area-weighted inlet and outlet pressures:

By contrast,

Figure 14 demonstrates a clear dependence of pressure drop on taper ratio. The total pressure drops decreases progressively with increasing taper, from 959.77 Pa in case R1 to 757.68 Pa in case R5. This reduction in hydraulic resistance lowers the pumping power demand, which in turn enhances the net power density, as summarized in

Table 3. Notably, the net power density increases from 0.294558 W/cm

2 in R1 to a peak of 0.297031 W/cm

2 in R5.

These results underline the significance of flow field geometry optimization. While taper ratio has little effect on gross power output, it strongly affects fluid dynamics and associated energy losses. Greater tapering, as seen in R4 and R5, promotes improved reactant distribution, facilitates water removal, and reduces transport resistance, leading to higher overall system efficiency. Thus, minimizing pressure drop emerges as a key strategy for maximizing the net performance of PEM fuel cells.

Table 3 shows how the taper ratio affects flow behavior and overall energy efficiency in SVTC channels. Although the power density output stays nearly the same across all cases, a lower taper ratio leads to a noticeable drop in both pressure loss and the power needed for pumping. As a result, the net power density increases steadily, with R5 reaching the highest value of 0.297031 W/cm

2. This suggests that more tapered channels help improve the distribution of reactants and remove excess water more effectively, while also lowering flow resistance. On the other hand, less tapered (more rectangular) channels reduce pressure drop but may limit reactant transport. Balancing these effects is important, as the design of the flow field is a pivotal aspect of PEMFC optimization, with the taper ratio emerging as a key geometric variable. This parameter critically influences the trade-off between efficient reactant distribution and the minimization of parasitic energy losses. In the subsequent part of this study, a comprehensive evaluation of the numerical findings is provided, exploring their consequences for overall cell efficacy and outlining the principal insights obtained from the computational analysis.

Consequently, the taper ratio is instrumental in augmenting PEMFC functionality through its regulation of mass transport phenomena and associated energy consumption. For clarity, this segment can be structured using subheadings to deliver a focused and accurate summary of the computational outcomes, their analysis, and the ensuing deductions.

4. Conclusions

In this study, a three-dimensional computational model was used to examine how different gas channel geometries affect the performance of a single-channel PEMFC. A computational analysis was conducted to evaluate a conventional rectangular channel against a SVTC, utilizing the ANSYS FLUENT software under steady-state and isothermal conditions.

The simulation results demonstrated that the SVTC configuration enhances fuel cell performance through improved reactant distribution and more effective water management, coupled with a reduction in pressure drop. These combined effects contributed to superior voltage stability and a marked improvement in power density relative to the conventional rectangular design. Out of all the tested taper ratios, the R5 configuration delivered the best performance, with the highest net power density of 0.297031 W/cm2 due to its efficient flow characteristics and reduced pumping power.

These findings demonstrate that channel geometry, specifically the taper ratio, has a strong impact on both transport behavior and overall efficiency. Optimizing this aspect of the flow field can lead to substantial gains in PEMFC operational performance and offers critical insights for advancing flow field architectures.

While the proposed SVTC design offers significant performance improvements in PEMFCs, it is crucial to consider the engineering application value and manufacturing feasibility of this innovative geometry.

Furthermore, the potential risks of stress concentration in metal bipolar plates, introduced by the tapered channels, were also addressed. Such stress concentrations have the potential to threaten the operational lifespan of the bipolar plates, thereby warranting dedicated studies to assess their implications for the long-term functional reliability of PEMFC systems.