Abstract

The growing global population has resulted in a higher demand for energy, leading researchers to prioritize the development of alternative energy sources and the improvement of current technologies. Nanofluids (NFs) are a promising method for enhancing heat transfer and efficiently utilizing solar thermal energy. This study describes the preparation of four NFs: two mono NFs of SiC and HfC containing nanoparticle concentrations ranging from 0.10–1.0 wt.%. Moreover, two hybrid NFs were synthesized within the same concentration range (0.10–1.0 wt.%) of SiC-HfC nanocomposites in proportions of 60 wt.% SiC-40 wt.% HfC and 40 wt.% SiC-60 wt.% HfC, all dispersed in a mixture of ethylene glycol (EG) and distilled water (50EG-50H2O). The materials were synthesized by carbothermal reduction, and the NFs were prepared using the two-step method. The NFs showed stable dispersion, with HfC and 40SiC-60HfC systems exhibiting the higher zeta potential (ζ) values. Viscosity remained largely unaffected by particle addition. The thermal diffusivity of the NFs was measured by the thermal lens spectroscopy (TLS) technique using 1:20 diluted samples. The hybrid nanofluid 40SiC-60HfC improved diffusivity by 66.93%, presenting a synergistic effect in its performance, highlighting its potential in clean energy systems.

1. Introduction

Over the years, the world’s population has increased, and with it, the need for energy consumption. For this reason, science has advanced in the search for energy sources that are friendly to the environment. An inexhaustible source is solar energy [1]. Solar energy can be captured through photoelectric systems (solar cells) and thermal systems (solar collectors). The last ones use heat transfer fluids to capture and transmit the energy in an efficient way [2]. The most frequently used heat transfer fluids are water, ethylene glycol (EG), propylene glycol, oils, and mixtures of some of them [3]. However, their thermal performance is limited due to their low thermal conductivity values [4].

To satisfy energy demand and reduce costs in solar absorption systems, it is necessary to increase the efficiency of the base fluids. One option to increase the heat transfer of the fluids is to add solid particles, which have a higher thermal conductivity compared with the base fluids [5]. Maxwell first proposed the addition of solid particles to heat transfer fluids (HTFs), observing improvements in the thermal conductivity of the HTFs [6]. However, as the particles are of millimeter or micrometer sizes, instability phenomena such as agglomeration and rapid sedimentation can occur, resulting in clogging of channels, pressure drops, pipe erosion, and increased viscosity. Therefore, even if thermal conductivity improvements are obtained, the use of these suspensions is not advisable because it increases the pumping power consumption [7]. To solve this problem, in 1995, Choi and Eastman [8] introduced the concept of nanofluids (NFs), which are colloidal dispersions of nano-sized materials (1–100 nm) in HTFs or base fluids. They observed a remarkable enhancement of thermal conductivity and a low increase in viscosity [9].

Nanoparticles (NPs) used in the preparation of NFs include metals such as gold (Au) [10], copper (Cu) [11] and silver (Ag) [12]; metal oxides such as copper oxide (CuO) [13], titanium dioxide (TiO2) [14], silicon dioxide (SiO2) [15], zinc oxide (ZnO) [16], iron oxide (Fe3O4) [17], zirconium dioxide (ZrO2) [18], and aluminum oxide (Al2O3) [19]; carbon-based materials such as graphene [20], carbon nanotubes [21], and diamond [22]; metal nitrides such as boron nitride (BN) [23], and aluminum nitride (AlN) [24]; and metal carbides such as titanium carbide (TiC) [25], and silicon carbide (SiC) [26].

The thermophysical properties of NFs can be further enhanced by incorporating different types of nanomaterials. These dispersions are known as hybrid NFs, which are obtained by dispersing nanocomposites or different NPs in the base fluid to provide novel or enhanced capabilities [27]. The main objective of using hybrid NFs is to improve heat transfer due to the synergistic effect of the different materials [28].

Several hybrid NFs investigations have been carried out using SiC as one of the components. Ramalingam et al. [29] prepared Al2O3/SiC NFs in a mixture of distilled water and EG. The dynamic viscosity decreases with increasing temperature. The highest thermal conductivity was 0.498 and 0.523 Wm−1K−1 at 60 °C and 65 °C for a volume concentration of 0.8%. Li et al. [30] synthesized silicon carbide-multiwall carbon nanotubes (SiC-MWCNTs) hybrid NFs in EG base fluid, improved the thermal conductivity by 32% at 1 wt.% particle concentration, and the viscosity increased with particle concentration and decreased with temperature. Despite the high thermal conductivity of MWCNTs, more processes are needed to achieve good dispersion and obtain stable NFs [31]. On the other hand, hafnium carbide (HfC) has been studied only as a mono nanofluid, and there are few reports using this material as NPs in NFs. Gokul et al. [32] prepared HfC NFs in EG-based fluid and studied their potential application in heat transfer by measuring the concentration-dependent thermal diffusivity. However, they report neither stability nor viscosity of their NFs. Concerning the EG-H2O mixture, Nikkan et al. [33] studied SiC NFs in water and EG-H2O mixture. They reported that NFs based on EG-H2O mixture showed better heat transfer characteristics than water-based NFs.

The main applications of hybrid NFs are in heat transfer, including automotive, aerospace, refrigeration, microfluidic devices, bioconvective flow, medical treatment, drug delivery, and solar energy [34,35,36]. Thermal conductivity and thermal diffusivity are considered the most important properties for evaluating the heat transfer performance of NFs, where improvement of these properties leads to better heat transfer efficiency of thermal systems [37]. However, most reports on SiC NFs have focused on investigating only thermal conductivity and a few studies on thermal diffusivity.

One point to consider is the difficulty in accurately determining thermal diffusivity using classical methods (3ω method, non-stationary hot wire, heat flow, protected hot plate, etc.) due to their significant disadvantages (thermal convection, low sensitivity to changes in physicochemical composition, etc.), which make them unsuitable for NFs. Thermal lens spectrometry (TLS) is a technique used to obtain thermal diffusivity in NFs, as it is possible to detect changes in the diffusion coefficient () with small variations in concentration (in the range of mg to µg/mL) and in the morphology of NPs (size, layer thickness, particle shape) in NFs [38]. TLS has limited applicability, for example, when the sample is very opaque or has high light scattering. With opaque samples, the TLS signal can be affected by background absorption, scattering, and thermal convection that distorts the thermal gradient, justifying its dilution [39]. To resolve opacity issues in NFs with high nanoparticle content, it may be necessary to take measures (such as dilution, optical clarity, minimizing dispersion) to ensure valid results [40].

In this study, silicon carbide and hafnium carbide (60SiC-40HfC and 40SiC-60HfC) nanocomposites are used as NPs in the preparation of hybrid NFs. The base fluid used was a mixture of EG and distilled water (50EG-50H2O); both were used because they are the most commonly used as refrigerants, and EG has very interesting properties for this application [41]. The experiments were carried out at room temperature and with a nanoparticle concentration of 0.10–1.0 wt.%. This research aims to analyze the stability and viscosity of hybrid SiC-HfC NFs and HfC NFs due to the good solar radiation absorption characteristics of these materials, and to determine the thermal diffusivity by TLS, keeping the viscosity and the temperature constant. The novelty of the current study relates to the determination of the thermal diffusivity of hybrid NFs containing SiC and HfC NPs, which have not been studied, and their possible application for heat transfer improvement.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. NFs Preparation

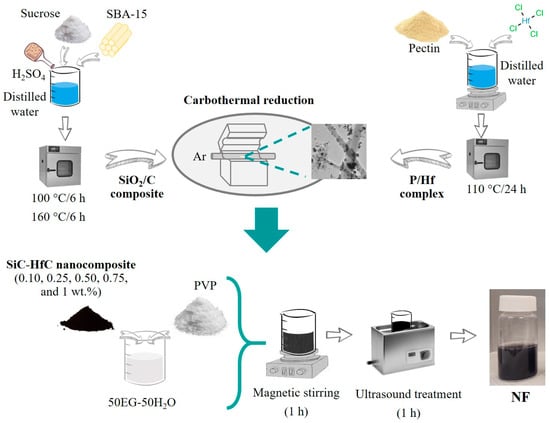

The NFs were prepared by the two-step method, first the nanocomposites were synthesized and then dispersed in the base fluid [42]. SiC-HfC nanocomposites were synthesized by carbothermal reduction of the silica/carbon composite (SiO2/C) and the pectin/hafnium complex (P/Hf). The SiO2/C composite was synthesized by impregnating silica SBA-15 with an aqueous solution of sucrose as carbon source and sulfuric acid (H2SO4). This solution was dried at 100 °C for 6 h, and subsequently the temperature was increased to 160 °C for another 6 h. The P/Hf complex was obtained by dissolving the pectin as carbon source in distilled water with continuous magnetic stirring at 40 °C. Then, hafnium tetrachloride (HfCl4) was added slowly to the pectin solution, and stirring was continued for 3 h at 40 °C. Afterward, the obtained solution was dried in an oven at 110 °C for 24 h. The carbothermal reduction of the SiO2/C compound and the P/Hf complex was carried out at 1600 °C for 3 h in argon atmosphere with some modifications [43].

The nanocomposites were dispersed in a 50EG-50H2O base fluid. To maintain their stability, the surfactant polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP K-30) at a concentration of 1:2 relative to the total mass of the NPs was added, and the pH was adjusted to 11 with NaOH to improve the stability of the NFs by increasing the repulsive forces between the NPs [44]. The pH was measured with a digital potentiometer (Orion Versa Star, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Prior to each measurement series, the pH meter was calibrated using standard buffer solutions at pH 4 (biphthalate), pH 7 (phosphate), and pH 10 (borate). In addition, magnetic agitation at 700 rpm and ultrasound treatment (model 75D, Aquasonic, VWR Scientific, Radnor, PA, USA), working at a frequency of 35 kHz) were used for 1 h each treatment. The methodology for the synthesis of the nanocomposites, as well as the preparation of the NFs, is shown graphically in Figure 1. The NFs were prepared with a percentage of 0.10, 0.25, 0.50, 0.75, and 1.0 wt.%.

Figure 1.

Schematic of SiC-HfC nanocomposite synthesis and two-step hybrid nanofluids (NFs) preparation process.

2.2. Nanocomposites Characterization

Before dispersing the NPs in the base fluid, these were characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD, DMAX 2200, RIGAKU, Tokyo, Japan) for the identification of the crystalline phases using a diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å). Data collection was performed in a range 2θ from 20° to 80° with a scanning speed of 2°/min, using a voltage of 40 kV and 40 mA current in the X-ray tube. The morphology, microstructure, and size of the NPs were characterized by transmission electron microscopy (TEM, JEM 2010 F, JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) operating at an accelerating voltage of 200 kV. The samples were prepared as follows: A small amount of powder was dispersed in ethanol by ultrasonic treatment for 1 min. Two drops of the suspended material were taken and deposited on 300-mesh Cu grids covered with a lacey carbon membrane. Once the dispersion was deposited on the grid, it was vacuum-dried for several hours. To determine the particle size distribution, TEM image analysis was performed using ImageJ and OriginPro 9.0 software (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA).

2.3. NFs Characterization

The surface charge and stability of the NFs were obtained by zeta potential (ζ) measurement using a Zetasizer Nano ZSP (Malvern Panalytical, Worcestershire, UK) using capillary cells (DTS1070,Malvern Panalytical, Worcestershire, UK). The zeta potential is determined by the electrophoretic motion of charged particles when influenced by an electric field [45]. Before each measurement of the zeta potential, a slight agitation was applied to each sample, and all measurements were carried out at 25 °C.

A compact modular rheometer (MCR 502, Anton Paar Gmbh, Graz, Austria) was used to obtain the viscosity values of the NFs. The measurement of the viscosity of NFs at different nanoparticle concentrations (0.10–1.0 wt.%) was performed at a shear rate of 100 s−1 and at different temperatures (20 to 80 °C). All experiments were performed with rotational method, without preshear, with a torque of 0.02–0.005 mN·m, and with disposable CC27 measurement geometry using 9 mL of sample for each NF.

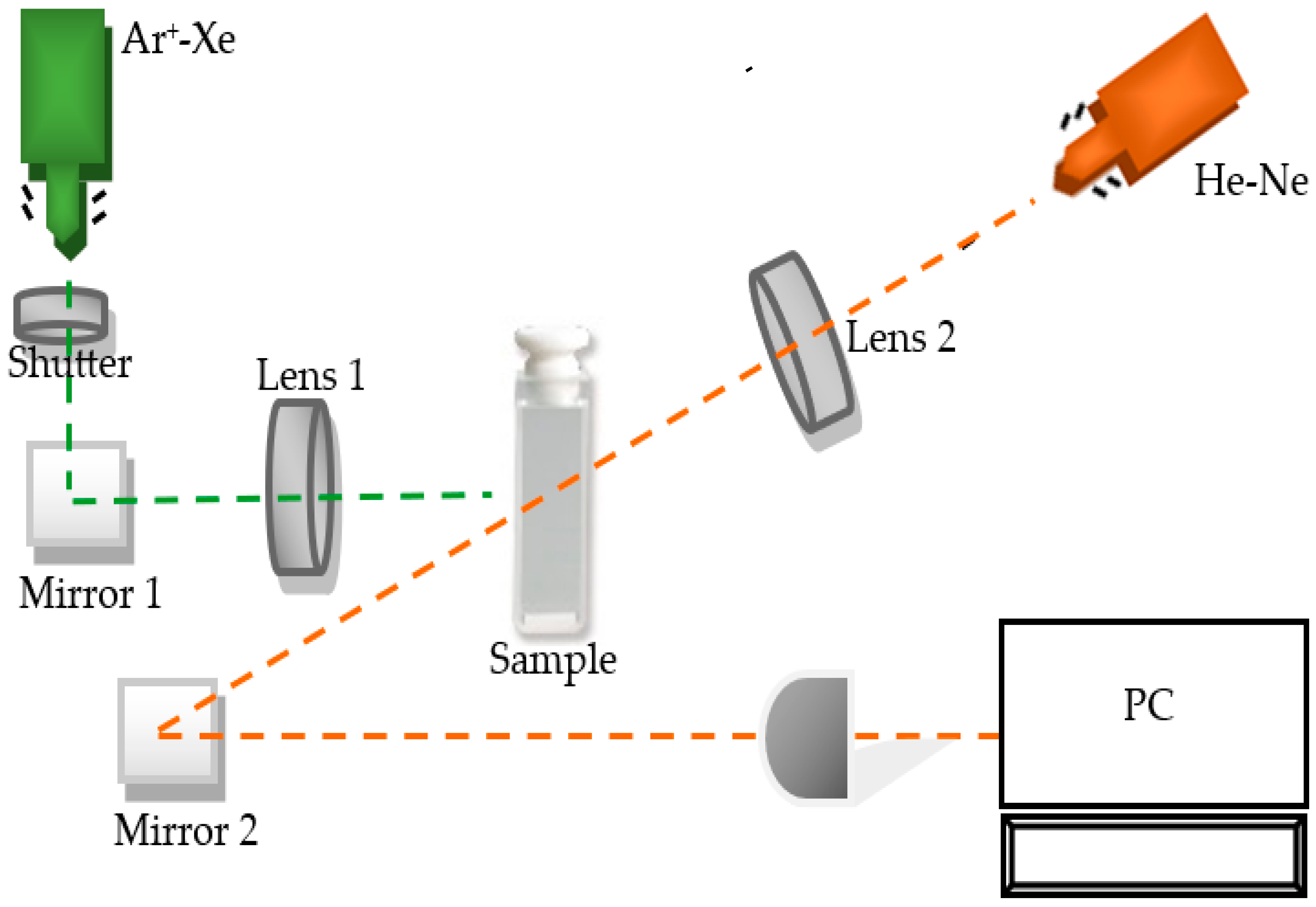

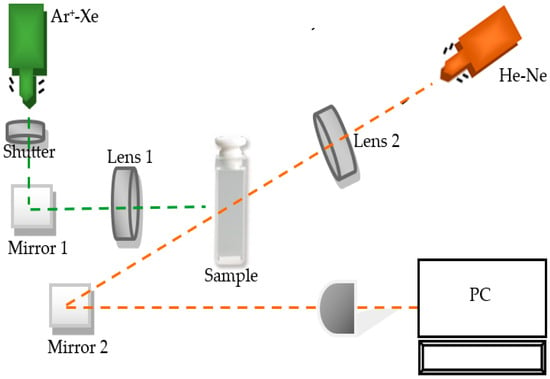

NFs thermal diffusivity measurements were carried out using a TLS arrangement with decoupled light beams described in Figure 2. This technique is a non-destructive method that is highly sensitive and precise, allowing it to detect small changes in the thermal properties of nanometric materials [32,46,47,48,49].

Figure 2.

Experimental setup for thermal lens technique (TLS).

The photothermal TLS consists of using a pulsed excitation laser beam, which hits a liquid sample, causing a change in its local temperature, and consequently causes variations in the refractive index of the material, creating a thermal lens, which modifies the path of a second laser beam (test laser). This results in a defocusing (or focusing) of the center of the probe’s laser beam. By measuring these changes in intensity as a function of time, the thermal diffusivity of the sample can be obtained. The experimental data were fitted using the theoretical Equation (1) by solving for the required values through Equations (2)–(5), with θ and tc (TLS characteristic) as fitting parameters [47,48].

where

where I(t) is the intensity of the probe laser beam at time (t) and normalized with I(0), which is the initial intensity of the probe laser beam at time t = 0; V is the beam waist ratio, with being the distance from the probe beam waist to the sample (∼8 cm) and being the probe beam confocal distance (6.56 cm); m is the beam spot size ratio, with () and () being the waist of the probe and excitation beam of the sample, respectively; is the characteristic thermal time constant of the formed thermal lens, is the laser wavelength of the probe beam (632 nm He-Ne 0.9 mW), D and k are the diffusivity and the thermal conductivity of the sample, θ is a fitting parameter associated with the phase shift of the probe beam; is the power of excitation beam (40 mW Ar+ Xe at 514 nm); α is the absorption coefficient, and l is the thickness of the sample (1 cm); and is the refractive index dependent on the temperature of the sample. It was observed that the laser beam could not pass through the samples.

Therefore, to use TL for measuring the contribution of nanocomposites to the fluid-based thermal properties, each sample was diluted 1:20, original formulation of the NFs: 50EG-50H2O base fluid, respectively, obtaining semitransparent samples. For the calibration of the TL technique, the base liquids, distilled water (), EG (), ethanol () were used [46,49].

A UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Lambda 35, PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) equipped with a 1 cm quartz cuvette was used to measure each nanofluid’s optical absorption coefficient (α). The same cuvettes were used for TLS measurements. To ensure reproducibility, each sample was measured six times, and the reported values match the average of those measurements. This is in agreement with the experimental and theoretical curves and was confirmed by typical fitting residuals of less than 3% and R2 > 0.98. With an uncertainty of ±5%, the spot sizes of the pump beam () and probe beam () were 4.0 × 10−3 cm and 1.8 × 10−3 cm, respectively.

3. Results

3.1. Nanocomposites

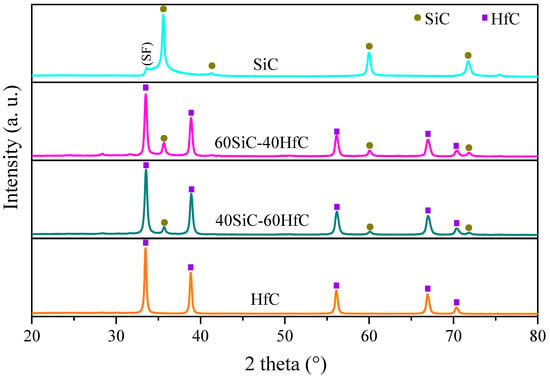

For SiC, HfC nanomaterials and their nanocomposites, we present the structural and morphological characterization studied before forming the NFs. Figure 3 shows the X-ray diffraction patterns of SiC, HfC, and SiC-HfC nanocomposites. The XRD pattern of SiC shows the peaks at 2θ at 35.6°, 41.3°, 60.0°, and 71.8°, which represent the (111), (200), (220), and (311) planes, respectively, which agree with the cubic phase (JCPDS No. 00-029-1129) [50]. In addition, the XRD pattern of SiC shows a small peak attributed to stacking faults (SF) in the (111) planes in the growth of nanowires (NWs) [51].

Figure 3.

XRD patterns of the synthesized materials by carbothermal reduction at 1600 °C: SiC, 60SiC-40HfC, 40SiC-60HfC, and HfC.

On the other hand, the XRD pattern of HfC presents five peaks at 2θ at 33.5°, 38.8°, 56.1°, 66.9°, and 70.3°, which correspond to the (111), (200), (220), (311), and (222) planes, respectively, of the cubic phase of HfC (JCPDS No. 00-039-1491), which agree with the literature [52,53]. The sharp and intense peaks suggest high crystallinity at the nanometric scale for both materials [54]. The XRD pattern of the nanocomposite materials shows sharp crystallized peaks for SiC and HfC, both in cubic phases.

However, the peaks of HfC are more intense than those of SiC, due to the high electron density of Hf relative to Si. The plane (111) peak of HfC (2θ = 33.5°) overlaps the peak attributed to stacking faults in the SiC because the diffraction grades of these peaks are similar. The presence of only two phases (SiC and HfC) indicates that there was no chemical reaction between them [55]. By carbothermal reduction at 1600 °C, most of the precursor material is converted to carbides with a minimum amount of hafnium oxide (HfO2) present.

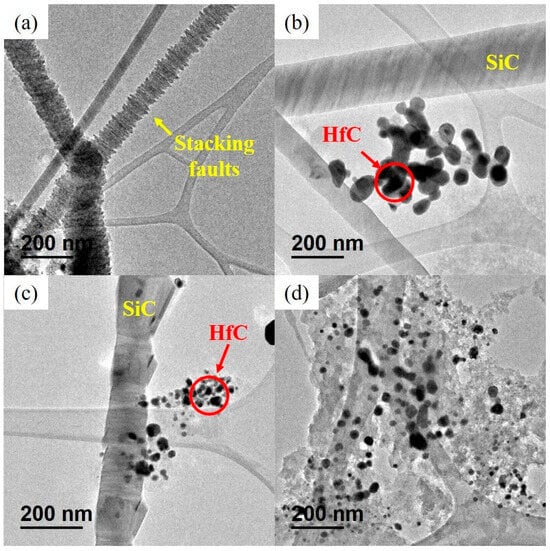

Figure 4 shows TEM micrographs of SiC, HfC, and SiC-HfC nanocomposite powders. The TEM micrograph of SiC (Figure 4a) shows NWs with diameters from a few nanometers to 200 nm and lengths of a few micrometers. In addition, the NWs have a variety of shapes and can be divided into straight NWs with a smooth surface and irregularly shaped NWs with a rough surface due to stacking faults, as observed in Figure 4a [56,57]. The presence of the stacking faults in the TEM micrographs of the SiC NWs corroborates the peak at 2θ = 33.6° of XRD. In the micrograph of HfC (Figure 4d), we observe quasi-spherical NPs with an average particle size of 15 nm; similar morphology and sizes are reported for HfC by other authors [58]. Residual carbon is observed in the HfC micrographs; the excess of carbon can suppress the growth of HfC particles [59], either by acting as a physical barrier to the diffusion of hafnium atoms or by promoting the formation of a larger number of HfC crystal nuclei than in a stoichiometric reaction, which would lead to the formation of smaller particles. Also, it can be deduced that the carbon precursor of HfC helps to the formation of SiC in nanocomposites, then the formation of larger NPs for HfC.

Figure 4.

TEM images of the synthesized materials by carbothermal reduction at 1600 °C; (a) SiC; (b) 60SiC-40HfC; (c) 40SiC-60HfC; and (d) HfC.

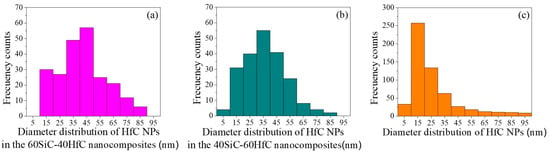

In the micrographs of nanocomposites (Figure 4b,c), SiC NWs and HfC particles are presented, distinguished by light and dark contrast, respectively [59]. The low contrast in the color of SiC (gray) with respect to the background is due to the low atomic number of Si (Z = 14); nevertheless, there is a high contrast between HfC (black) with SiC and the background, due to the high atomic number of Hf (Z = 72) [60]. No residual carbon is observed in nanocomposites; therefore, the particle sizes of HfC in the nanocomposites tend to be larger than in HfC material itself. For the 60SiC-40HfC and 40SiC-60HfC nanocomposites, the average HfC size was 45 and 35 nm, respectively (Figure 5a,b).

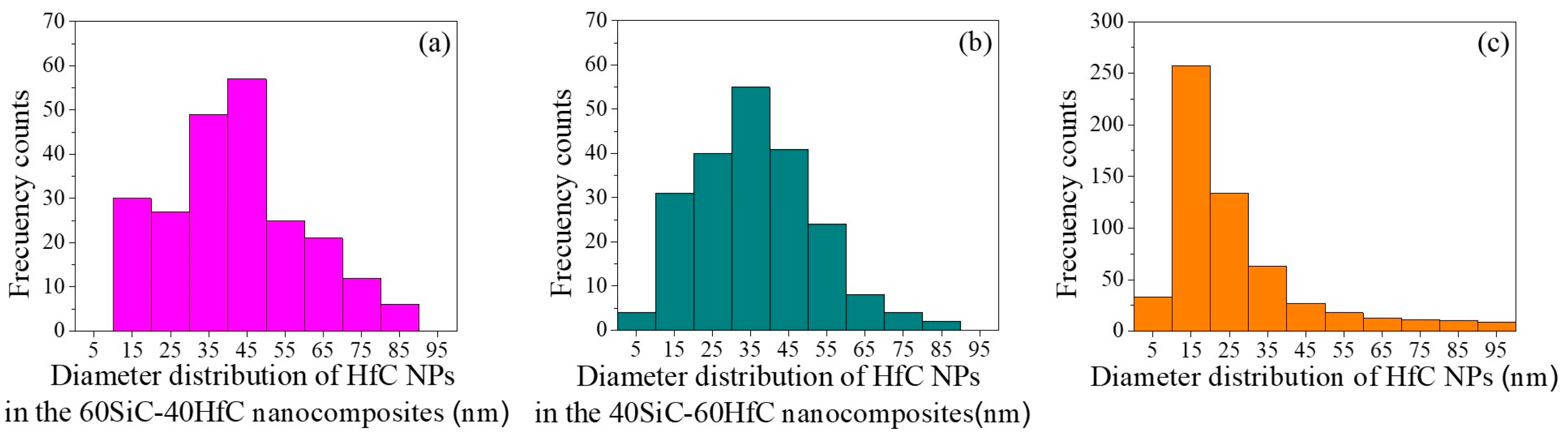

Figure 5.

HfC particle size distribution: (a) 60SiC-40HfC; (b) 40SiC-60HfC; and (c) HfC.

Figure 5 shows the size distribution of HfC NPs in the 60SiC-40HfC, 40SiC-60HfC, and pure HfC samples. The average HfC NPs sizes in these materials were approximately 45 nm, 35 nm, and 15 nm, respectively.

Smaller NPs exhibit more pronounced Brownian motion—the random movement that facilitates their dispersion, collision, and suspension within the base fluid. This dynamic behavior promotes a more homogeneous distribution of NPs, thereby preventing sedimentation and agglomeration over time and enhancing the long-term stability of the NPs suspension [61]. These observations are consistent with the measured zeta potential values in the present study: the 40SiC-60HfC and HfC NPs, which contain smaller particles, exhibited the highest zeta potential levels. Such stability is essential for maintaining the improved properties of the fluid over time and ensuring consistent thermal performance.

3.2. NFs

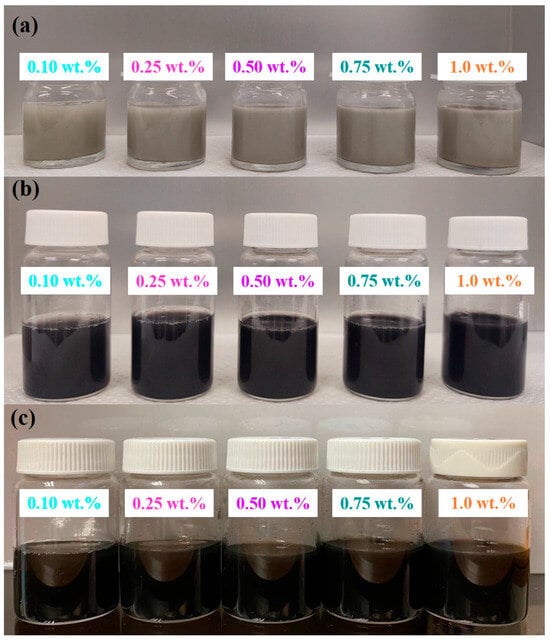

The NFs were prepared with percentages of 0.10, 0.25, 0.50, 0.75, and 1.0 wt.%, their photographs are shown in Figure 6. A gray color is observed for SiC NFs, while a black color is observed for NFs containing HfC. The prepared NFs appear homogeneous upon visual inspection. A visual inspection of HfC NFs at different concentrations over time (1, 7, 14, and 21 days) was performed; photographs are shown in Figure S1.

Figure 6.

Photographs of the several hybrid NFs in 50EG-50H2O mixture prepared by magnetic stirring and ultrasound treatment in their different weight percentages of NPs: (a) SiC; (b) 40SiC_60HfC; (c) HfC NFs.

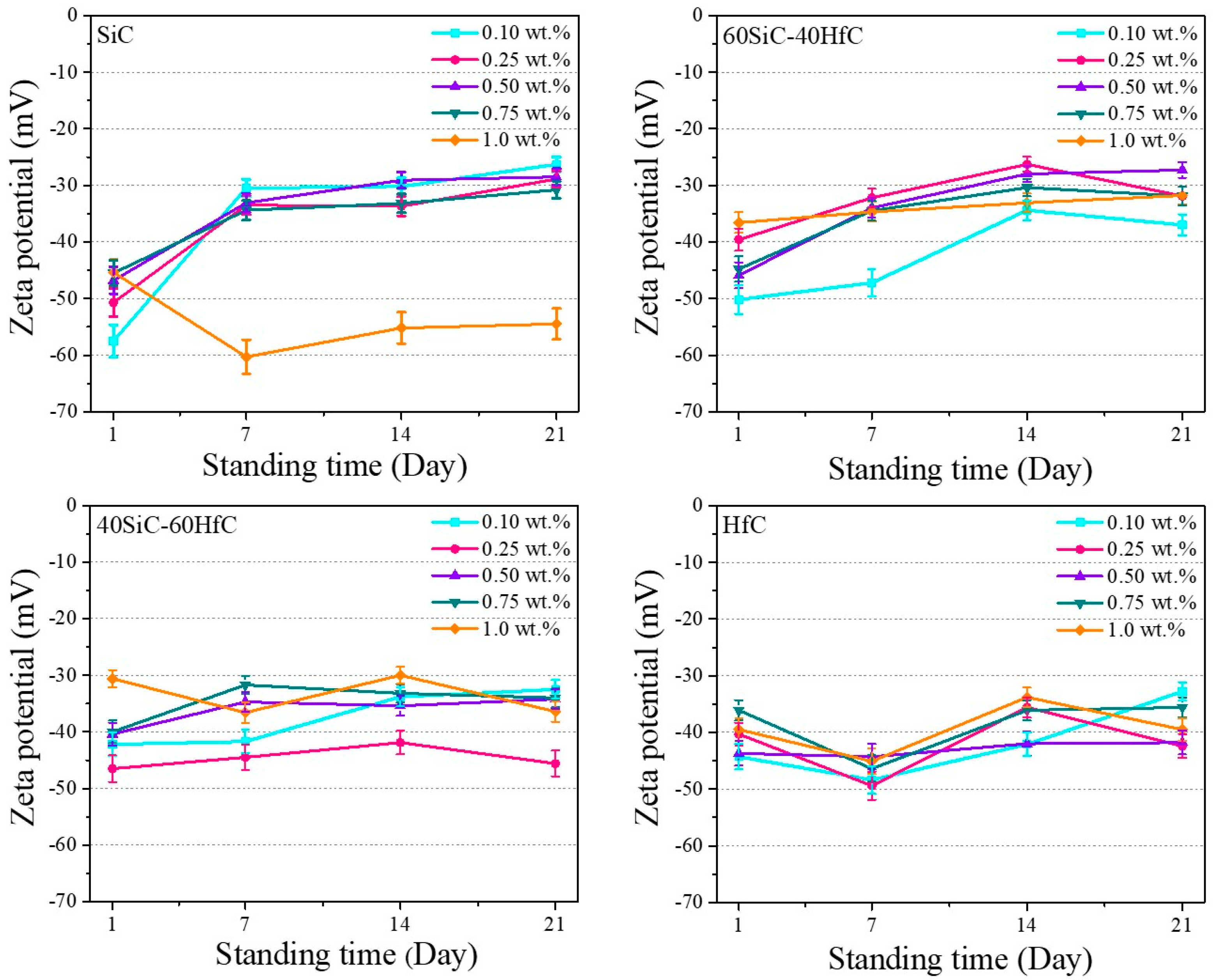

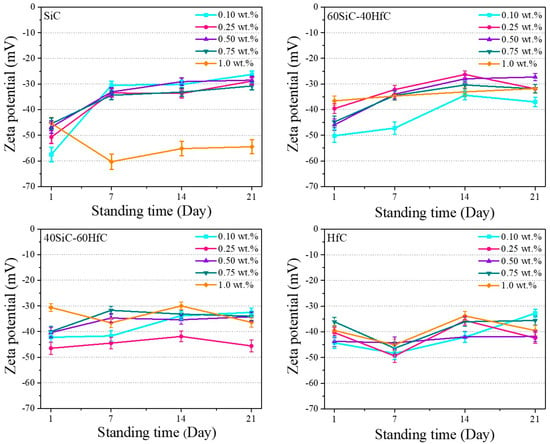

Figure 7 and Table 1 show the zeta potential graphs of the different NFs prepared as a function of the standing time. In general, it is observed that the zeta potential values of NFs decrease slightly as the standing time increases. This phenomenon is presented in NFs prepared with SiC in previous research [61]. Zeta potential measurements offer insight into the magnitude of electrostatic repulsion between suspended NPs, serving as a key indicator of colloidal stability. A high zeta potential value (positive or negative) reflects strong interparticle repulsion that avoids particle aggregation by preventing them from approaching one another [42]. For SiC NFs at 1.0 wt.%, significantly high values of negative zeta potentials are observed. This behavior can be attributed to an insufficient amount of PVP at this concentration to fully coat the SiC NWs. As a result, the electrostatic repulsion arising from surface hydroxyl groups—formed during pH adjustment—predominates over the steric stabilization that could be provided by the PVP. A suspension is considered stable when the magnitude of the zeta potential is greater than |ζ| > 30 mV [62].

Figure 7.

Zeta potential of SiC-HfC hybrid NFs in 50EG-50H2O mixture as a function of standing time.

Table 1.

Zeta potential of SiC-HfC hybrid NFs in 50EG-50H2O mixture as a function of standing time.

For these NFs systems, stabilization techniques were applied during their preparation. Ultrasonic treatment leads to the production of stable NFs by breaking nanoparticle clustering [63]. Magnetic stirring improves stability by breaking the clustering; however, using only magnetic stirring does not ensure the stability of the suspensions over a long period of time [64], so magnetic stirring, ultrasound treatment, use of PVP, and pH adjustment were used in our systems [65]. The last two techniques modify the surface charge of the NPs and NFs by seeking an electrostatic or steric repulsion between them. By adjusting the pH to 11, and with the presence of PVP molecules, higher zeta potential values were achieved, since these conditions allow interparticle repulsion by steric and electrostatic interactions.

The NFs of HfC and the 40SiC-60HfC nanocomposite in their different weight percentages present |ζ| > 30 mV in the analyses performed at 1, 7, 14, and 21 days. This may be due to the uniformity in size and morphology of the HfC reported in TEM micrographs (Figure 4d). In the case of SiC NFs and 60SiC-40HfC nanocomposite, they present values around −30 mV from day 14 of standing. However, all these values remain very close to the threshold, showing |ζ| > 25 mV (Table 1). Several authors have reported that nanosystems with |ζ| > 25 mV also tend to exhibit high stability [66,67,68]. The stability of NPs helps increase the thermal conductivity of NFs [67]. It is likely that the NFs with a higher amount of HfC exhibit slightly higher zeta potential values because they are smaller in size and therefore present a larger specific surface area. It is plausible that the PVP does not form a complete coating over all particles, leading to a predominance of electrostatic repulsion—arising from surface hydroxyl groups during pH adjustment—over the steric stabilization provided by the PVP.

In this regard, the barely perceptible signal for HfO2 in XRD (Figure 3) indicates its presence at very low concentrations. However, its presence in NFs can only contribute to the colloidal stability of HfC NPs, since contact with water promotes the formation of -OH groups. These groups facilitate hydrogen bonding with the carbonyl groups of PVP, promoting the coating of the NPs by PVP and thus steric repulsion. This effect is in addition to that caused by the formation of HfO2 on the surface due to the interaction of HfC with water.

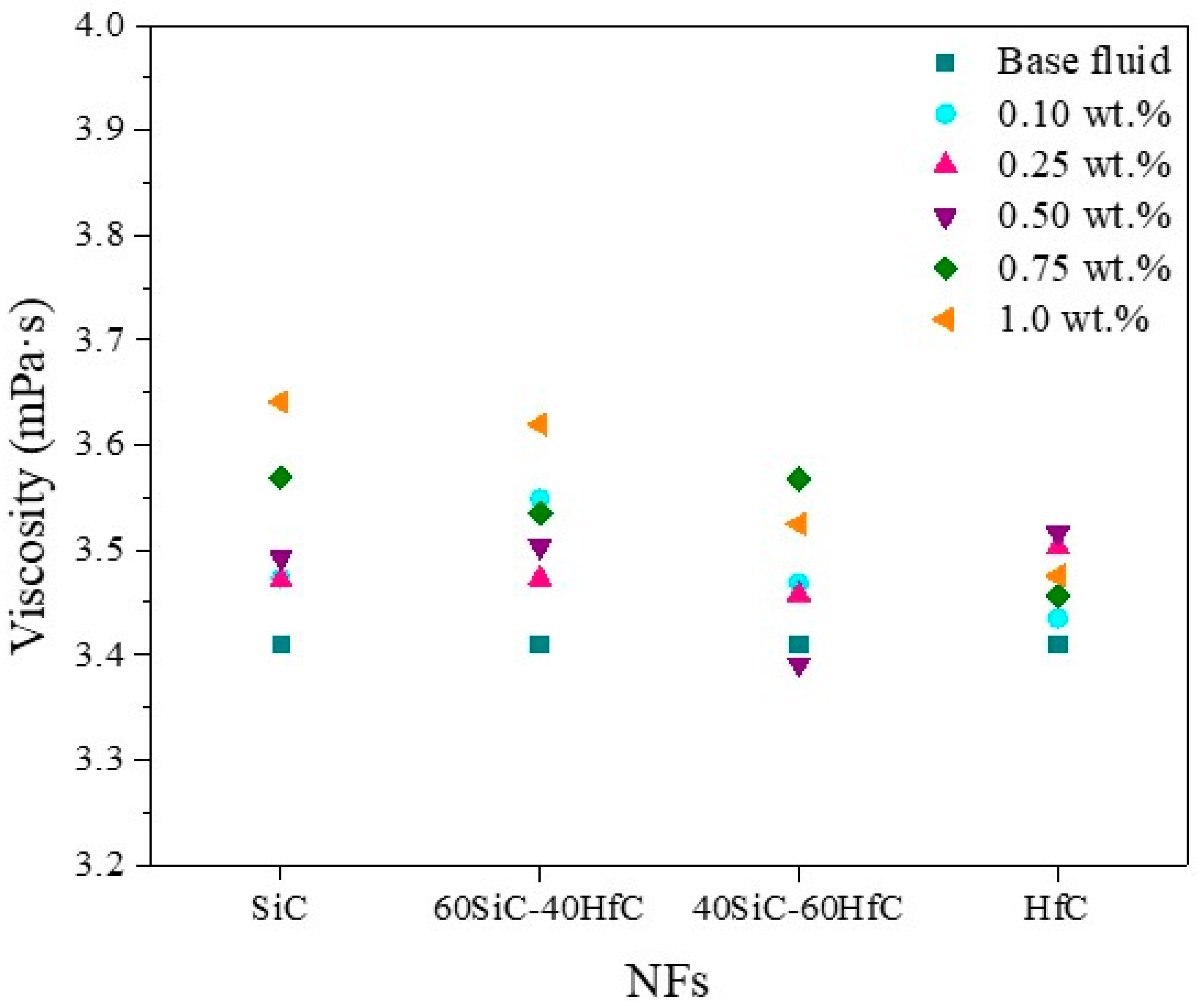

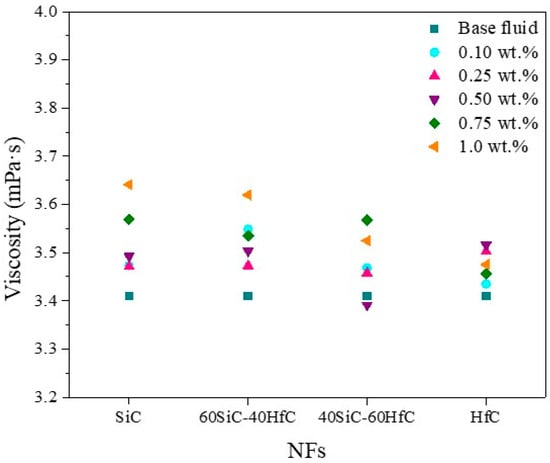

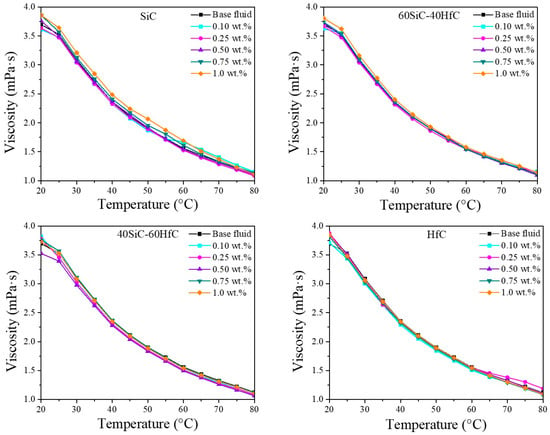

A rheological analysis of the base fluids was performed to determine their viscosity and behavior. The rheological tests revealed the behavior of the base fluids at 20 °C, obtaining Newtonian fluids due to the fact that the viscosity value is constant with respect to the shear rate (Figures S2 and S3). The viscosity at room temperature of the individual NFs with different weight percentages of NPs is detailed in Figure 8. The increase in viscosity of the NFs prepared in this work is very small as the weight percentage of SiC-HfC NPs increases. This indicates that their low viscosity makes them suitable for heat-transfer applications without requiring additional pumping power. In general, for NFs in which SiC is the predominant component, an increase in nanoparticle concentration leads to a rise in viscosity. According to the literature, the viscosity increases with the concentration of NPs, and the smaller the increase, the better the performance because a large increase in viscosity raises the cost of the process [69]. The effect on viscosity caused by the addition of PVP in some reported studies is detailed below: Luo et al. [70] investigated the rheological properties of SiC NFs in ethanol with three dispersants: tetramethylammonium hydroxide (TMAH), polyethyleneimine (PEI), and PVP. The lowest viscosity values were found in NFs with PVP. The PVP dispersant content was 1% to 6 wt.%, with lower viscosity values obtained at 5 wt.%. Rehman et al. [71] examined the effects of eight different surface-active agents on the stability, rheological behavior, and thermophysical properties of hybrid NFs composed of Al2O3 and TiO2 dispersed in a water-EG mixture (60:40). Among the surfactants evaluated, PVP demonstrated the highest suitability for Al2O3–TiO2 hybrid NFs, primarily due to the enhanced colloidal stability, moderate viscosity profile, and improved thermal performance it imparted to the system.

Figure 8.

Viscosity at room temperature of SiC-HfC hybrid NFs in 50EG-50H2O mixture.

The viscosity of the different NFs was also measured in a temperature range from 20 to 80 °C (Figure 9). Viscosity decreases with increasing temperature. This trend has been reported for hybrid NFs of SiC [72]. Viscosity reductions were up to about 70% for all NFs prepared over the entire temperature range. Viscosity decreases with an increase in temperature due to a reduction in density and an increase in kinetic energy. This behavior has been reported in other investigations of SiC [73]. As the kinetic energy of the NPs increases, the velocity of the NPs increases while the contact time decreases. Consequently, the adhesion between NPs is weakened and leads to a decrease in the viscosity of the NFs [32]. Although SiC is in the quasi-spherical form with particle sizes larger than HfC particles, the viscosity increase is similar in all NFs, because SiC is also in the form of NWs, which rotate like quasi-spherical particles and align themselves with respect to the flow direction [74], resulting in very little increase in viscosity even when they are micrometer lengths. Currently, no viscosity studies on HfC NFs have been reported; however, several investigations have evaluated the viscosity of SiC NFs in different base fluids. Ajeeb et al. [37] analyzed the viscosity of SiC NFs prepared with a base fluid composed of 70 vol.% distilled water and 30 vol.% EG, using SiC concentrations ranging from 0.01 to 0.05 vol.%. The viscosities they reported are lower than those obtained in our systems, likely due to the distinct H2O-EG ratio employed. Nonetheless, their observations are generally consistent with our results: the NFs exhibited Newtonian behavior, with viscosity increasing as nanoparticle concentration increased and decreasing with increasing temperature. Li et al. [75] investigated the rheological behavior of SiC NFs formulated with a water/EG mixture at a 60:40 volume ratio and containing SiC from 0 to 1.0 vol.%. The SiC NPs, with an average diameter of 30 nm, produced stable suspensions through the addition of PVP as a dispersant. Although the viscosities they reported are higher than those obtained in our systems, the overall trends are consistent: the NFs exhibit Newtonian behavior, and viscosity increases with nanoparticle volume fraction and decreases as temperature rises.

Figure 9.

Viscosity of SiC-HfC hybrid NFs in 50EG-50H2O mixture at different temperatures.

The thermal diffusivity values of the base fluid, base fluid + PVP, and different NFs at 0.5 wt.% of NPs are presented in Figure 10. All the NFs values of thermal diffusivity obtained were higher than those of the base fluid and the base fluid with surfactant (PVP). The increase in thermal diffusivity of the nanofluid depends on many factors, such as heat transfer assisted by Brownian motion, reduction in thermal resistance, and specific heat capacity of the nanofluid. Solids have comparatively lower heat capacity than liquids; therefore, the specific heat capacity of the nanofluid is always lower than that of the base liquid, thus the thermal diffusivity of the nanofluid improves [76]. Moreover, the higher the particle concentration, the higher the thermal diffusivity [77]. In addition, another reason may be that the liquid forms layers around the NPs, which may act as a thermal bridge to improve diffusivity [78]. It is observed that the HfC NFs show better thermal diffusivity compared with SiC NFs, due to their smaller nanoparticle size. Besides, we observed that the 40SiC-60HfC NF displays better values of thermal diffusivity. Reports in the literature indicate that thermal diffusivity is governed by multiple factors, including nanoparticle size and morphology, surface capping or functionalization, the physicochemical properties of the base fluid, the intensity of Brownian motion, and the specific heat capacity of the system [79]. The 40SiC-60HfC NFs contain a higher amount of HfC NPs, which are smaller than SiC. According to the literature, a smaller size increases the surface-to-volume ratio and, therefore, thermal diffusivity [80,81]. Another factor that helps this NF is that it contains SiC in the form of NWs, which have lengths of up to microns and diameters in nanometers, resulting in a high aspect ratio (length-to-diameter ratio) [82]. It is also necessary to point out that the large number of stacking faults present in SiC NWs (Figure 4a) could hinder the mean free path of phonons in the heat transfer mechanism for the NWs. Furthermore, the size of the HfC NPs, around 35 nm in the hybrid NF, could be suitable for ballistic transport mechanisms, which, together with the contribution of SiC, brings out a synergistic effect, presenting better thermal diffusivity values with respect to the NFs of individual components.

Figure 10.

Thermal diffusivity of 50EG-50H2O base fluids and SiC-HfC hybrid NFs at 0.5 wt.% of NPs.

Table 2 summarizes the obtained fitting parameters and the calculated thermal diffusivities for each nanofluid. The parameters θ and tc were obtained from the time evolution of thermal lens signal results (Figure S4). From the comparison of thermal diffusivity values (Table 2) for the 40SiC-60HfC nanofluid () with respect to the weighted average value of the mono NFs SiC () and HfC (), which is , we observe an improvement of 14.8%. This improvement cannot be explained solely by the contribution of the constituent nanomaterials; rather, it may indicate the presence of synergistic mechanisms within the hybrid nanofluid.

Table 2.

Fitting parameters for θ and tc and the calculated, , of 50EG-50H2O base fluids and SiC-HfC hybrid NFs.

Several factors could contribute to this improvement, from the anisotropic morphology of SiC, which could facilitate percolation networks, to the potentially denser packing promoted by the HfC nanoparticles, which may reduce interfacial thermal resistance. Furthermore, the stability of the nanofluid dispersion, promoted by steric repulsion due to the presence of PVP, along with the electrostatic repulsion, supports Brownian motion and nanoparticle interaction.

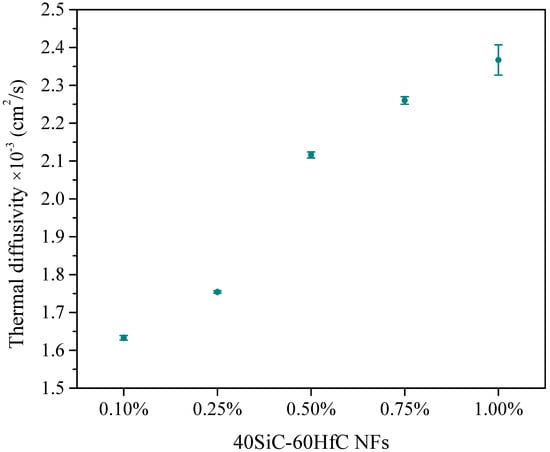

Figure 11 shows the thermal diffusivity of 40SiC-60HfC NFs at different concentrations (0.10–1.0 wt.%). This nanofluid was chosen because it exhibited the highest thermal diffusivity among the NFs analyzed. Again, this agrees with the zeta potential values obtained (Figure 7). This nanofluid presents zeta potential values higher than the absolute value of −30 mV in the analyses performed at 1, 7, 14, and 21 days. Therefore, this was the most stable nanofluid studied, stability being one of the factors that increases thermal diffusivity [83]. With increasing concentration of NPs, the thermal diffusivity value also increases. This phenomenon has been reported in other investigations [82]. The lowest thermal diffusivity value obtained for 40SiC-60HfC nanofluid was at 0.1 wt.%, while the highest value was at 1.0 wt.%, the percentage improvement of thermal diffusivity was 44.95% between them. The 40SiC-60HfC hybrid nanofluid at 1.0 wt.% showed the best thermal diffusivity values; the percentage improvement of thermal diffusivity is 66.93% compared with the base fluid + PVP. Given that there is an increase in the thermal diffusivity of the NFs with respect to the base fluids, it is expected that there will also be an increase in thermal conductivity values of the NFs with respect to the base fluids [37]. An increase in thermal diffusivity indicates an increase in heat transfer, which is an important property for heat transfer in solar cell applications because it decreases the manufacturing size and cost of the equipment [84].

Figure 11.

Thermal diffusivity of 40SiC-60HfC NFs in 50EG-50H2O mixture with different particle concentrations.

Table 3 shows a comparison of the thermal diffusivity values obtained in the present work with works reported in the literature. The diffusivity shown by the hybrid NFs of this work was higher than in other reports. However, in NFs prepared from SiC and BN in concentrations of 0.01-0.05 vol.% in the mixture of 70EG-30H2O, they found that thermal diffusivity was also increased with the addition of NPs [37], as in our systems. A similar phenomenon occurs with HfC NFs: as the concentration of NPs increases, thermal diffusivity increases. It is reported that at higher concentrations, NPs self-assemble into long-chain structures, thereby reducing Brownian motion and improving heat transfer by conduction, which explains the increase in thermal diffusivity [32]. As for the work carried out with Au NPs, they also obtained higher thermal diffusivity values as the concentration of NPs increased. However, they used H2O, EG, and ethanol as base fluids, obtaining better results with H2O [80].

Table 3.

Comparison of the thermal diffusivity values obtained in the present work with works reported in the literature.

The TLS measurements performed on the 1:20 diluted samples exhibit reliable comparative trends among NFs with different compositions. The controlled dilution preserves the same particle-to-fluid ratio across all formulations, providing a consistent basis for comparison while minimizing multiple scattering and ensuring measurement stability. Although the diffusivity values obtained from the diluted samples only represent the absolute thermal performance of the undiluted NFs, they serve as a diagnostic reference to evaluate the relative changes in heat-transport behavior induced by variations in nanoparticle type and concentration. This approach allows us to isolate the effect of composition on thermal diffusivity while maintaining the practical relevance of the observed trends.

4. Conclusions

In this work, several samples of hybrid, stable, and homogeneous NFs were prepared using the SiC, HfC, and SiC-HfC nanocomposite dispersed in the 50EG-50H2O mixture by the two-step method for five weight percentages of 0.10 to 1.0 wt.%. The stability of the prepared samples was corroborated by zeta potential values. The dispersion of these NFs was stable for at least 3 weeks and, according to the zeta potential results, the NFs showing the best stability were the NFs containing the smallest NPs, in this case, HfC. The NFs of HfC and 40SiC-60HfC nanocomposite present values of |ζ| > 30 mV in the analyses performed at 1, 7, 14, and 21 days. In the case of SiC NFs and 60SiC-40HfC nanocomposite, they present values around −30 mV from day 14 of standing. In general, the addition of NPs does not cause significant changes in the viscosity of the base fluid. The viscosity variation is lower in HfC NFs compared with SiC-containing NFs, due to the nanoparticle size and homogeneity of HfC. It is observed that HfC NFs showed better thermal diffusivity compared with SiC NFs. On the other hand, the hybrid NF (40SiC-60HfC) at 1.0 wt.% showed the best thermal diffusivity values; the percentage improvement of thermal diffusivity is 66.93% compared with the base fluid + PVP, exhibiting a better thermal diffusivity compared with individual NFs, presenting a synergistic effect in their performance. Therefore, research on SiC-HfC hybrid NFs is important, novel, and necessary for future applications in heat transport technologies for clean energy, such as solar cells.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/fluids10120316/s1, Figure S1: Photographs of the HfC NFs in 50EG-50H2O mixture prepared by magnetic stirring and ultra-sound treatment as a function of standing time; (a) 1 day; (b) 7 days; (c) 14 days; and (d) 21 days; Figure S2. Viscosity vs. shear rate of SiC-HfC hybrid NFs in 50EG-50H2O mixture; Figure S3. Shear stress vs. shear rate of SiC-HfC hybrid NFs in 50EG-50H2O mixture; Figure S4. TL signal of (a) base fluid, (b) base fluid + PVP, (c) HfC 0.5 wt.%, (d) SiC 0.5 wt.%, (e) 60SiC-40HfC 0.5 wt.%, (f) 40SiC-60HfC 0.5 wt.%, (g) 40SiC-60HfC 0.1 wt.%, (h) 40SiC-60HfC 0.25 wt.%, (i) 40SiC-60HfC 0.75 wt.%, and (j) 40SiC-60HfC 1.0 wt.%.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.G.C.-M. and J.C.T.-C.; methodology, C.A.G.-M., C.S.R.-W., J.L.J.-P. and R.G.-F.; software, C.A.G.-M., J.L.J.-P., R.G.-F. and C.A.P.-R.; validation, C.S.R.-W., L.G.C.-M. and J.C.T.-C.; formal analysis, C.A.G.-M., C.S.R.-W., C.A.P.-R. and J.C.T.-C.; investigation, C.A.G.-M.; resources, J.C.T.-C.; data curation, C.A.G.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, C.A.G.-M. and C.S.R.-W.; writing—review and editing, L.G.C.-M., C.S.R.-W., J.L.J.-P. and J.C.T.-C.; visualization, C.A.G.-M.; supervision, L.G.C.-M. and J.C.T.-C.; project administration, J.C.T.-C.; funding acquisition, J.C.T.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by SECIHTI, in projects 242943 and 269519, and for the Ph.D. scholarship No. 298147.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the use of the facilities at the MET-UNISON Laboratory of the University of Sonora and the UPIITA-IPN.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EG | Ethylene glycol | |

| HfC | Hafnium Carbide | |

| HTFs | Heat transfer fluids | |

| MWCNTs | Multiwalled carbon nanotubes | |

| NFs | Nanofluids | |

| NPs | Nanoparticles | |

| PEI | Polyethyleneimine | |

| PVP | Polyvinylpyrrolidone | |

| SiC | Silicon carbide | |

| TLS | Thermal lens spectroscopy | |

| TMAH | Tetramethylammonium hydroxide | |

| vol.% | Volume percentage | |

| wt.% | Weight percentage | |

| Nomenclature | ||

| Symbol | Description | Unit |

| Refractive index dependent on the temperature | ||

| Thermal diffusivity | ||

| Intensity of the probe laser beam | ||

| Intensity of the probe laser beam at time 0 | ||

| Thermal conductivity | ||

| Thickness of the sample | ||

| Beam spot size ratio | ||

| Power excitation beam | mW | |

| Time | ||

| Characteristic thermal time constant of the formed thermal lens | cm | |

| Beam waist radio | cm | |

| Excitation beam of the sample | cm | |

| Waist of the probe | cm | |

| Distance from the probe beam waist to the sample | cm | |

| Probe beam confocal distance | cm | |

| α | Absorption coefficient | |

| ζ | Zeta potential | mV |

| |ζ| | Absolute value zeta potential | mV |

| θ | Fitting parameter associated with the phase shift of the probe beam | |

| Laser wavelength of the probe beam | nm | |

References

- Hamzat, A.K.; Omisanya, M.I.; Sahin, A.Z.; Ropo Oyetunji, O.; Abolade Olaitan, N. Application of Nanofluid in Solar Energy Harvesting Devices: A Comprehensive Review. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 266, 115790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, Z.; Lee, M.; Cho, H. Thermophysical Advancements and Stability Dynamics in Nanofluids for Solar Energy Harvesting: A Comprehensive Review. Renew. Energy 2025, 248, 123052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, U.S.; Sangwai, J.S.; Byun, H.-S. A Comprehensive Review on the Recent Advances in Applications of Nanofluids for Effective Utilization of Renewable Energy. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 207, 114901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alktranee, M.; Al-Yasiri, Q.; Saeed Mohammed, K.; Al-Lami, H.; Bencs, P. Energy and Exergy Assessment of a Photovoltaic-Thermal (PVT) System Cooled by Single and Hybrid Nanofluids. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2024, 24, 100769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahamude, A.S.F.; Kamarulzaman, M.K.; Harun, W.S.W.; Kadirgama, K.; Ramasamy, D.; Farhana, K.; Bakar, R.A.; Yusaf, T.; Subramanion, S.; Yousif, B. A Comprehensive Review on Efficiency Enhancement of Solar Collectors Using Hybrid Nanofluids. Energies 2022, 15, 1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, J.; Soni, A.; Barai, D.P.; Bhanvase, B.A. A Minireview on Nanofluids for Automotive Applications: Current Status and Future Perspectives. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2023, 219, 119428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morozova, M.A.; Osipov, A.A.; Maksimovskiy, E.A.; Zaikovsky, A. V Optical Properties, Thermal Conductivity, and Viscosity of Graphene-Based Nanofluids for Solar Collectors. Nano-Struct. Nano-Objects 2024, 40, 101409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.U.S. Enhancing Thermal Conductivity of Fluids With Nanoparticles. Am. Soc. Mech. Eng. Fluids Eng. Div. FED 1995, 231, 99–105. [Google Scholar]

- Dewanjee, D.; Kundu, B. A Review of Applications of Green Nanofluids for Performance Improvement of Solar Collectors. Renew. Energy 2025, 240, 122182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, M.; Xu, B.; Shi, L.; Zhou, T.; Zheng, N.; Sun, Z. Self-Assembled Au-CQDs Nanofluids with Excellent Solar Absorption and Medium–High Temperature Stability for Solar Energy Harvesting. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 672, 765–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, D.K.; Kumar, S.P.; Shenoy, U.S. Design, Synthesis, and Characterization of Stable Copper Nanofluid with Enhanced Thermal Conductivity. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 39, 109129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavari, R.; Abed, A.M.; Akbari, O.A.; Marzban, A.; Baghaei, S. Numerical Study of Flow and Free Convection of Water/Silver Nanofluid in a Circular Cavity Influenced by Hot Fluid Flow. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2022, 153, 104378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadhim, S.A.; Hammoodi, K.A.; Askar, A.H.; Rashid, F.L.; Abdul Wahhab, H.A. Feasibility Review of Using Copper Oxide Nanofluid to Improve Heat Transfer in the Double-Tube Heat Exchanger. Results Eng. 2024, 24, 103227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtadha, T.K.; dil Hussein, A.A.; Alalwany, A.A.H.; Alrwashdeh, S.S.; Al-Falahat, A.M. Improving the Cooling Performance of Photovoltaic Panels by Using Two Passes Circulation of Titanium Dioxide Nanofluid. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2022, 36, 102191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, H.A.; Togun, H.; Abed, A.M.; Mohammed, H.I.; Armaghani, T. Cooling Lithium-Ion Batteries with Silicon Dioxide -Water Nanofluid: CFD Analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 208, 115007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuok, L.P.; Elkady, M.; Zkria, A.; Yoshitake, T.; Nour Eldemerdash, U. Evaluation of Stability and Functionality of Zinc Oxide Nanofluids for Enhanced Oil Recovery. Micro Nano Syst. Lett. 2023, 11, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toma, S.H.; Santos, J.J.; da Silva, D.G.; Huila, M.F.G.; Toma, H.E.; Araki, K. Improving Stability of Iron Oxide Nanofluids for Enhanced Oil Recovery: Exploiting Wettability Modifications in Carbonaceous Rocks. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 212, 110311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajeena, A.M.; Farkas, I.; Víg, P. A Comparative Experimental Study on Thermal Conductivity of Distilled Water-Based Mono Nanofluids with Zirconium Oxide and Silicon Carbide for Thermal Industrial Applications: Proposing a New Correlation. Int. J. Thermofluids 2023, 20, 100424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtadha, T.K.; Hussein, A.A. Optimization the Performance of Photovoltaic Panels Using Aluminum-Oxide Nanofluid as Cooling Fluid at Different Concentrations and One-Pass Flow System. Results Eng. 2022, 15, 100541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, R.; Shen, J.; Tang, X.; Zhao, L.; Gao, J. Performances of a Tailored Vegetable Oil-Based Graphene Nanofluid in the MQL Internal Cooling Milling. J. Manuf. Process. 2025, 134, 814–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajeeb, W.; Oliveira, M.S.A.; Martins, N.; Murshed, S.M.S. Forced Convection Heat Transfer of Non-Newtonian MWCNTs Nanofluids in Microchannels under Laminar Flow. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2021, 127, 105495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alklaibi, A.M.; Sundar, L.S.; Sousa, A.C.M. Experimental Analysis of Exergy Efficiency and Entropy Generation of Diamond/Water Nanofluids Flow in a Thermosyphon Flat Plate Solar Collector. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2021, 120, 105057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Tiwari, A.K. Performance Evaluation of Evacuated Tube Solar Collector Using Boron Nitride Nanofluid. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2022, 53, 102466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chammam, W.; Farooq, U.; Sediqmal, M.; Waqas, H.; Yasmin, S.; Zulfiqar, F.; Liu, D.; Khan, S.A. Estimation of Heat Transfer Coefficient and Friction Factor with Showering of Aluminum Nitride and Alumina Water Based Hybrid Nanofluid in a Tube with Twisted Tape Insert. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 23071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abhilash, P.; Raghupati, U.; Nanda Kumar, R. Design and CFD Analysis of Hair Pin Heat Exchanger Using Aluminium and Titanium Carbide Nanofluids. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 39, 764–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezekwem, C.; Dare, A. Thermal and Electrical Conductivity of Silicon Carbide Nanofluids. Energy Sources Part A Recover. Util. Environ. Eff. 2024, 46, 11320–11338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahariq, I.; khan, D.; Ghazwani, H.A.; Shah, M.A. Enhancing Heat and Mass Transfer in MHD Tetra Hybrid Nanofluid on Solar Collector Plate through Fractal Operator Analysis. Results Eng. 2024, 24, 103163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra Haeri, S.; Khiadani, M.; Ramezanzadeh, B.; Kariman, H.; Zargar, M. Photo-Thermal Conversion Properties of Hybrid NH2-MIL-125/TiN/EG Nanofluids for Solar Energy Harvesting. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 258, 124607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalingam, S.; Dhairiyasamy, R.; Govindasamy, M. Assessment of Heat Transfer Characteristics and System Physiognomies Using Hybrid Nanofluids in an Automotive Radiator. Chem. Eng. Process.—Process Intensif. 2020, 150, 107886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, H.; Luo, B. The Thermophysical Properties and Enhanced Heat Transfer Performance of SiC-MWCNTs Hybrid Nanofluids for Car Radiator System. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2021, 612, 125968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zeng, G.; Lei, X. The Stability, Optical Properties and Solar-Thermal Conversion Performance of SiC-MWCNTs Hybrid Nanofluids for the Direct Absorption Solar Collector (DASC) Application. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2020, 206, 110323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokul, V.; Swapna, M.S.; Raj, V.; Saritha Devi, H.V.; Sankararaman, S. Concentration-Dependent Thermal Duality of Hafnium Carbide Nanofluid for Heat Transfer Applications: A Mode Mismatched Thermal Lens Study. Int. J. Thermophys. 2021, 42, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikkam, N.; Saleemi, M.; Haghighi, E.B.; Ghanbarpour, M.; Khodabandeh, R.; Muhammed, M.; Palm, B.; Toprak, M.S. Fabrication, Characterization and Thermophysical Property Evaluation of SiC Nanofluids for Heat Transfer Applications. Nano-Micro Lett. 2014, 6, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejo, J.P.; Prado, J.I.; Lugo, L. Hybrid or Mono Nanofluids for Convective Heat Transfer Applications. A Critical Review of Experimental Research. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2022, 203, 117926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, N.; Mondal, M.K.; Mandal, D.K.; Manna, N.K.; Gorla, R.S.R.; Chamkha, A.J. A Narrative Loom of Hybrid Nanofluid-Filled Wavy Walled Tilted Porous Enclosure Imposing a Partially Active Magnetic Field. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2022, 217, 107028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, N.; Mandal, D.K.; Manna, N.K.; Benim, A.C. Enhanced Energy and Mass Transport Dynamics in a Thermo-Magneto-Bioconvective Porous System Containing Oxytactic Bacteria and Nanoparticles: Cleaner Energy Application. Energy 2023, 263, 125775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajeeb, W.; Murshed, S.M.S. Characterization of Thermophysical and Electrical Properties of SiC and BN Nanofluids. Energies 2023, 16, 3768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khabibullin, V.R.; Usoltseva, L.O.; Mikheev, I.V.; Proskurnin, M.A. Thermal Diffusivity of Aqueous Dispersions of Silicon Oxide Nanoparticles by Dual-Beam Thermal Lens Spectrometry. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georges, J. Advantages and Limitations of Thermal Lens Spectrometry over Conventional Spectrophotometry for Absorbance Measurements. Talanta 1999, 48, 501–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khabibullin, V.R.; Mikheev, I.V.; Proskurnin, M.A. Features of High-Precision Photothermal Analysis of Liquid Systems by Dual-Beam Thermal Lens Spectrometry. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, M.; Lou, D.; Wang, D.; Younes, H.; Hong, H.; Chen, H.; Peterson, G.P. Ti3C2Tx MXene Nanofluids with Enhanced Thermal Conductivity. Chem. Thermodyn. Therm. Anal. 2022, 8, 100077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.A.; Hasnain, S.M.M.; Pandey, S.; Tapalova, A.; Akylbekov, N.; Zairov, R. Review on Nanofluids: Preparation, Properties, Stability, and Thermal Performance Augmentation in Heat Transfer Applications. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 32328–32349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceballos-Mendivil, L.G.; Tánori-Córdova, J.C.; Baldenebro-López, J.A.; Soto-Rojo, R.A.; Baldenebro-López, F.J. Synthesis and Characterization of HfC/SiC Ceramic Nanoparticles. Microsc. Microanal. 2018, 24, 1110–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younes, H.; Mao, M.; Sohel Murshed, S.M.; Lou, D.; Hong, H.; Peterson, G.P. Nanofluids: Key Parameters to Enhance Thermal Conductivity and Its Applications. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2022, 207, 118202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Kumar, A.; Alam, M.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, P.; Goyat, V. A Study of Morphology, UV Measurements and Zeta Potential of Zinc Ferrite and Al2O3 Nanofluids. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 59, 1034–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punnakkal, V.S.; Francis, F.; Pius, M.; Santhi, A.; Anila, E.I. Thermal Diffusivity Study of One-Pot Synthesised Polypyrrole Silver Nanocomposite by Thermal Lens Method. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 34, 105151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna-Sánchez, J.L.; Jiménez-Pérez, J.L.; Carbajal-Valdez, R.; Lopez-Gamboa, G.; Pérez-González, M.; Correa-Pacheco, Z.N. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Jalapeño Chili Extract and Thermal Lens Study of Acrylic Resin Nanocomposites. Thermochim. Acta 2019, 678, 178314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netzahual-Lopantzi, Á.; Sánchez-Ramírez, J.F.; Jiménez-Pérez, J.L.; Cornejo-Monroy, D.; López-Gamboa, G.; Correa-Pacheco, Z.N. Study of the Thermal Diffusivity of Nanofluids Containing SiO2 Decorated with Au Nanoparticles by Thermal Lens Spectroscopy. Appl. Phys. A 2019, 125, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sindhu Swapna, M.N.; Raj, V.; Cabrera, H.; Sankararaman, S.I. Thermal Lensing of Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotube Solutions as Heat Transfer Nanofluids. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2021, 4, 3416–3425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Yuan, S.; Zou, J.; Wu, Z.; Li, X.; Guo, W.; Tan, S.; Wang, H.; Hao, Y.; Ruan, H. Harnessing a Silicon Carbide Nanowire Photoelectric Synaptic Device for Novel Visual Adaptation Spiking Neural Networks. Nanoscale Horiz. 2024, 9, 1813–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.-Y.; Chi, C.-C.; Hsu, W.-K.; Ouyang, H. Synthesis of SiC/SiO2 Core–Shell Nanowires with Good Optical Properties on Ni/SiO2/Si Substrate via Ferrocene Pyrolysis at Low Temperature. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajpoot, S.; Nonavinakere Vinod, K.; Fang, T.; Xu, C. Synthesis of Hafnium Carbide (HfC) via One-Step Selective Laser Reaction Pyrolysis from Liquid Polymer Precursor. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2025, 108, e20650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.O.; Caraballa, P.H.; Bregman, A.G.; Bell, N.S.; Nicholas, J.R.; Ringgold, M.; Treadwell, L.J. Fabrication of Tantalum and Hafnium Carbide Fibers via ForcespinningTM for Ultrahigh-Temperature Applications. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 2021, 6672746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, S.; Fan, S.; Ma, X.; Ma, Y.; Luan, C.; Ma, J.; Liu, C. Ablation Performance of C/HfC-SiC Composites with in-Situ HfSi2/HfC/SiC Multi-Phase Coatings under 3000 °C Oxyacetylene Torch. Corros. Sci. 2022, 200, 110218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Meng, Z.; Xiao, B.; Li, J.; Liu, K.; Yang, M.; Zhang, S.; Goto, T.; Tu, R. Mechanical, Electrical and Thermal Properties of HfC-HfB2-SiC Ternary Eutectic Composites Prepared by Arc Melting. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2021, 41, 6943–6951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Yang, Z.; Tang, X.; Yue, Y. Strong Structural Occupation Ratio Effect on Mechanical Properties of Silicon Carbide Nanowires. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 11386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Jeon, W.B.; Moon, J.S.; Lee, J.; Han, S.-W.; Bodrog, Z.; Gali, A.; Lee, S.-Y.; Kim, J.-H. Strong Zero-Phonon Transition from Point Defect-Stacking Fault Complexes in Silicon Carbide Nanowires. Nano Lett. 2021, 21, 9187–9194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Y. Preparation of HfC-SiC Ultra-High-Temperature Ceramics by the Copolycondensation of HfC and SiC Precursors. J. Mater. Sci. 2022, 57, 4467–4480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Q.; Yu, Z.; Riedel, R.; Ionescu, E. Single-Source-Precursor Synthesis and High-Temperature Evolution of a Boron-Containing SiC/HfC Ceramic Nano/Micro Composite. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2021, 41, 3002–3012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amandine, V.; Cédric, M.; Sergio, M.; Patricia, D. An ImageJ Tool for Simplified Post-Treatment of TEM Phase Contrast Images (SPCI). Micron 2019, 121, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajeena, A.M.; Farkas, I.; Víg, P. A Comprehensive Experimental Study on Thermal Conductivity of ZrO2-SiC/DW Hybrid Nanofluid for Practical Applications: Characterization, Preparation, Stability, and Developing a New Correlation. Arab. J. Chem. 2023, 16, 105346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, M.S.; Khazaei, M.; Misaghi, M.; Koosheshi, M.H. Improving the Stability of Nanofluids via Surface-Modified Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles for Wettability Alteration of Oil-Wet Carbonate Reservoirs. Mater. Res. Express 2022, 9, 035005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urmi, W.T.; Rahman, M.M.; Kadirgama, K.; Ramasamy, D.; Maleque, M.A. An Overview on Synthesis, Stability, Opportunities and Challenges of Nanofluids. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 41, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Panigrahi, P.K. Stability of Nanofluid: A Review. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2020, 174, 115259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrozifard, A.; Goshayeshi, H.R.; Zahmatkesh, I.; Chaer, I.; Salahshour, S.; Toghraie, D. Experimental Optimization of the Performance of a Plate Heat Exchanger with Graphene Oxide/Water and Al2O3/Water Nanofluids. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2024, 59, 104525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shnoudeh, A.J.; Hamad, I.; Abdo, R.W.; Qadumii, L.; Jaber, A.Y.; Surchi, H.S.; Alkelany, S.Z. Synthesis, Characterization, and Applications of Metal Nanoparticles. In Biomaterials and Bionanotechnology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 527–612. [Google Scholar]

- dos Santos, C.C.; Viali, W.R.; Viali, E.S.N.; Marques, R.F.C.; Jafelicci Junior, M. Colloidal Stability Study of Fe3O4-Based Nanofluids in Water and Ethylene Glycol. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2021, 146, 509–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Zhang, M.; Chen, K.; Wang, M. Nano-Emulsion Prepared by High Pressure Homogenization Method as a Good Carrier for Sichuan Pepper Essential Oil: Preparation, Stability, and Bioactivity. LWT 2022, 154, 112779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porgar, S.; Oztop, H.F.; Salehfekr, S. A Comprehensive Review on Thermal Conductivity and Viscosity of Nanofluids and Their Application in Heat Exchangers. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 386, 122213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, G.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, J.; Zhang, J.; Sun, Y.; Shen, Q.; Zhang, L. Study on Rheological Behavior of Micro/Nano-Silicon Carbide Particles in Ethanol by Selecting Efficient Dispersants. Materials 2020, 13, 1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.; Yaqub, S.; Ali, M.; Nazir, H.; Shahzad, N.; Shakir, S.; Liaquat, R.; Said, Z. Effect of Surfactants on the Stability and Thermophysical Properties of Al2O3+TiO2 Hybrid Nanofluids. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 391, 123350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akilu, S.; Sharma, K.V.; Aklilu, T.B.; Azman, M.S.M.; Bhaskoro, P.T. Temperature Dependent Properties of Silicon Carbide Nanofluid in Binary Mixtures of Glycerol-Ethylene Glycol. Procedia Eng. 2016, 148, 774–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Li, X.; Zou, C.; Wang, T.; Lei, X. Rheological Behavior of Ethylene Glycol-Based SiC Nanofluids. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2015, 84, 925–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Atrens, A.; Stokes, J.R. A Review of Nanocrystalline Cellulose Suspensions: Rheology, Liquid Crystal Ordering and Colloidal Phase Behaviour. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 275, 102076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Zou, C. Thermo-Physical Properties of Water and Ethylene Glycol Mixture Based SiC Nanofluids: An Experimental Investigation. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2016, 101, 412–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, S.; Francis, F.; Joseph, S.A.; Kala, M.S. Enhanced Thermal Diffusivity of Water Based ZnO Nanoflower/RGO Nanofluid Using the Dual-Beam Thermal Lens Technique. Nano-Struct. Nano-Objects 2021, 28, 100784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Pérez, J.L.; López-Gamboa, G.; Sánchez-Ramírez, J.F.; Correa-Pacheco, Z.N.; Netzahual-Lopantzi, A.; Cruz-Orea, A. Thermal Diffusivity Dependence with Highly Concentrated Graphene Oxide/Water Nanofluids by Mode-Mismatched Dual-Beam Thermal Lens Technique. Int. J. Thermophys. 2021, 42, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, D.; Francis, F.; Pius, M.; Ani Joseph, S. Thermal Diffusivity Measurement of Fe2O3-Au Nanofluid Composite Using Thermal Lens Technique. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nideep, T.K.; Ramya, M.; Nampoori, V.P.N.; Kailasnath, M. The Size Dependent Thermal Diffusivity of Water Soluble CdTe Quantum Dots Using Dual Beam Thermal Lens Spectroscopy. Phys. E Low-Dimens. Syst. Nanostructures 2020, 116, 113724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Muñoz, G.A.; Balderas-López, J.A.; Ortega-Lopez, J.; Pescador-Rojas, J.A.; Salazar, J.S. Thermal Diffusivity Measurement for Urchin-like Gold Nanofluids with Different Solvents, Sizes and Concentrations/Shapes. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2012, 7, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.P.; Choi, S.U.S. Role of Brownian Motion in the Enhanced Thermal Conductivity of Nanofluids. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2004, 84, 4316–4318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, M.; Anugop, B.; Vijesh, K.R.; Balan, V.; Nampoori, V.P.N.; Kailasnath, M. Morphology and Concentration-Dependent Thermal Diffusivity of Biofunctionalized Zinc Oxide Nanostructures Using Dual-Beam Thermal Lens Technique. Mater. Lett. 2022, 323, 132599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, F.; Anila, E.I.; Joseph, S.A. Dependence of Thermal Diffusivity on Nanoparticle Shape Deduced through Thermal Lens Technique Taking ZnO Nanoparticles and Nanorods as Inclusions in Homogeneous Dye Solution. Optik 2020, 219, 165210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senthilkumar, D.; Jumpholkul, C.; Wongwises, S. Enhancing Thermal Behavior of SiC Nanopowder and SiC/Water Nanofluid by Using Cryogenic Treatment. Adv. Mater. Process. Technol. 2018, 4, 402–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutras, K.N.; Peppas, G.D.; Fetsis, T.T.; Tegopoulos, S.N.; Charalampakos, V.P.; Kyritsis, A.; Yiotis, A.G.; Gonos, I.F.; Pyrgioti, E.C. Dielectric and Thermal Response of TiO2 and SiC Natural Ester Based Nanofluids for Use in Power Transformers. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 79222–79236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Wang, C.; Wen, H.; Liu, L. Research and Optimization of Thermophysical Properties of Sic Oil-Based Nanofluids for Data Center Immersion Cooling. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2022, 131, 105863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.M.; Yunus, W.M.M. Study of the Effect of Volume Fraction Concentration and Particle Materials on Thermal Conductivity and Thermal Diffusivity of Nanofluids. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2011, 50, 085201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltaninejad, S.; Husin, M.S.; Sadrolhosseini, A.R.; Zamiri, R.; Zakaria, A.; Moksin, M.M.; Gharibshahi, E. Thermal Diffusivity Measurement of Au Nanofluids of Very Low Concentration by Using Photoflash Technique. Measurement 2013, 46, 4321–4327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).