Evaluation Model of Microhemodynamics in Finger Skin at Arterial Occlusion and Post-Occlusive Hyperemia

Abstract

1. Introduction

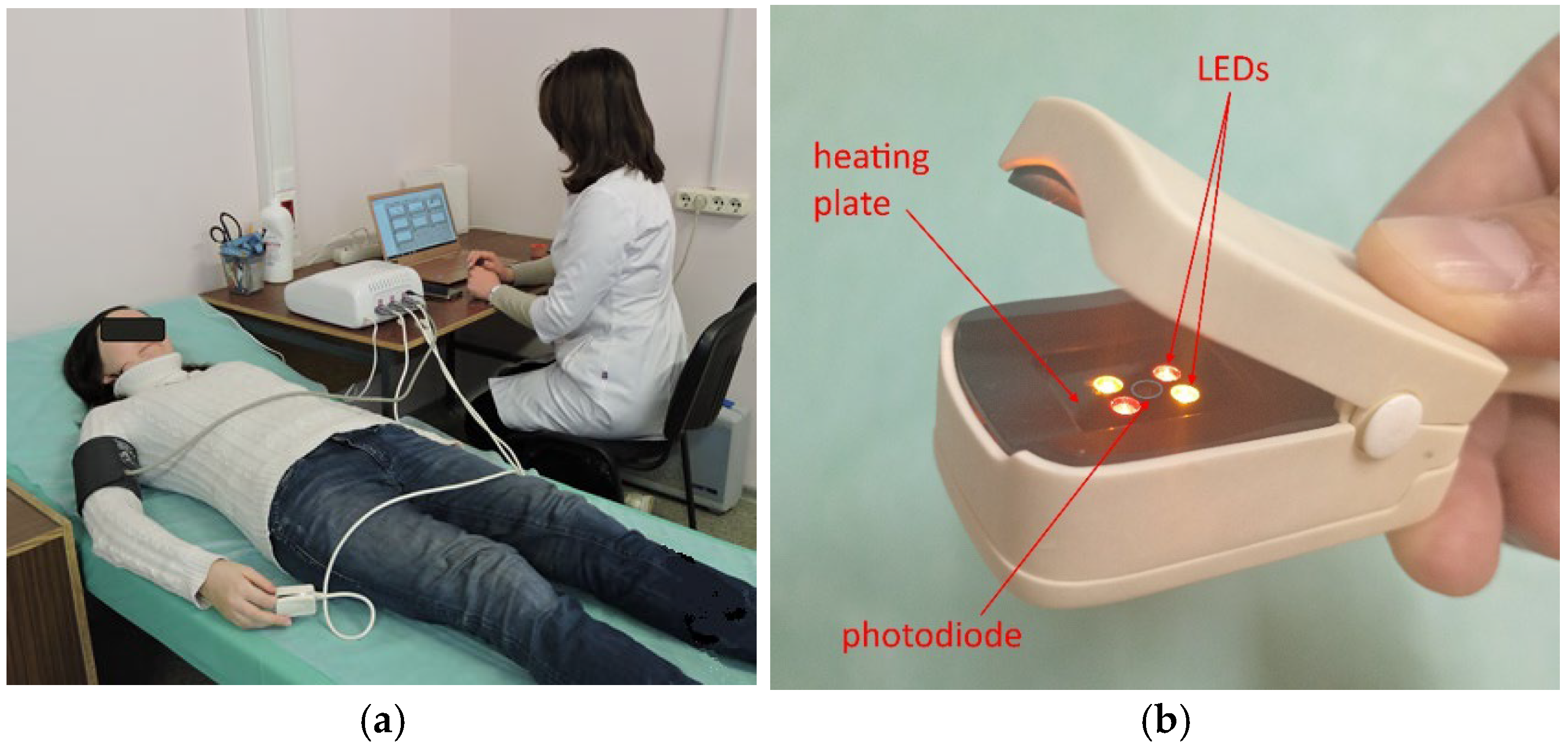

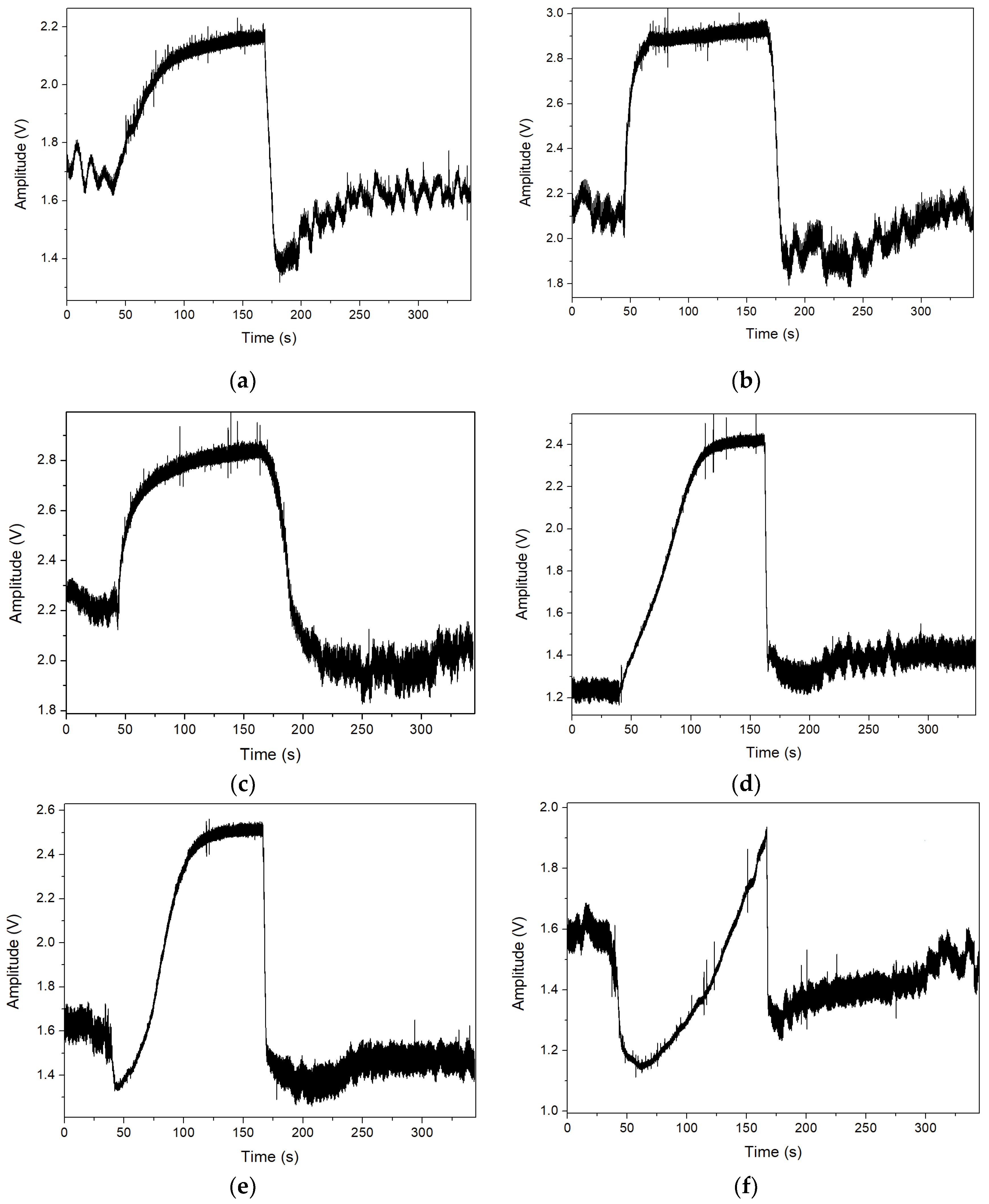

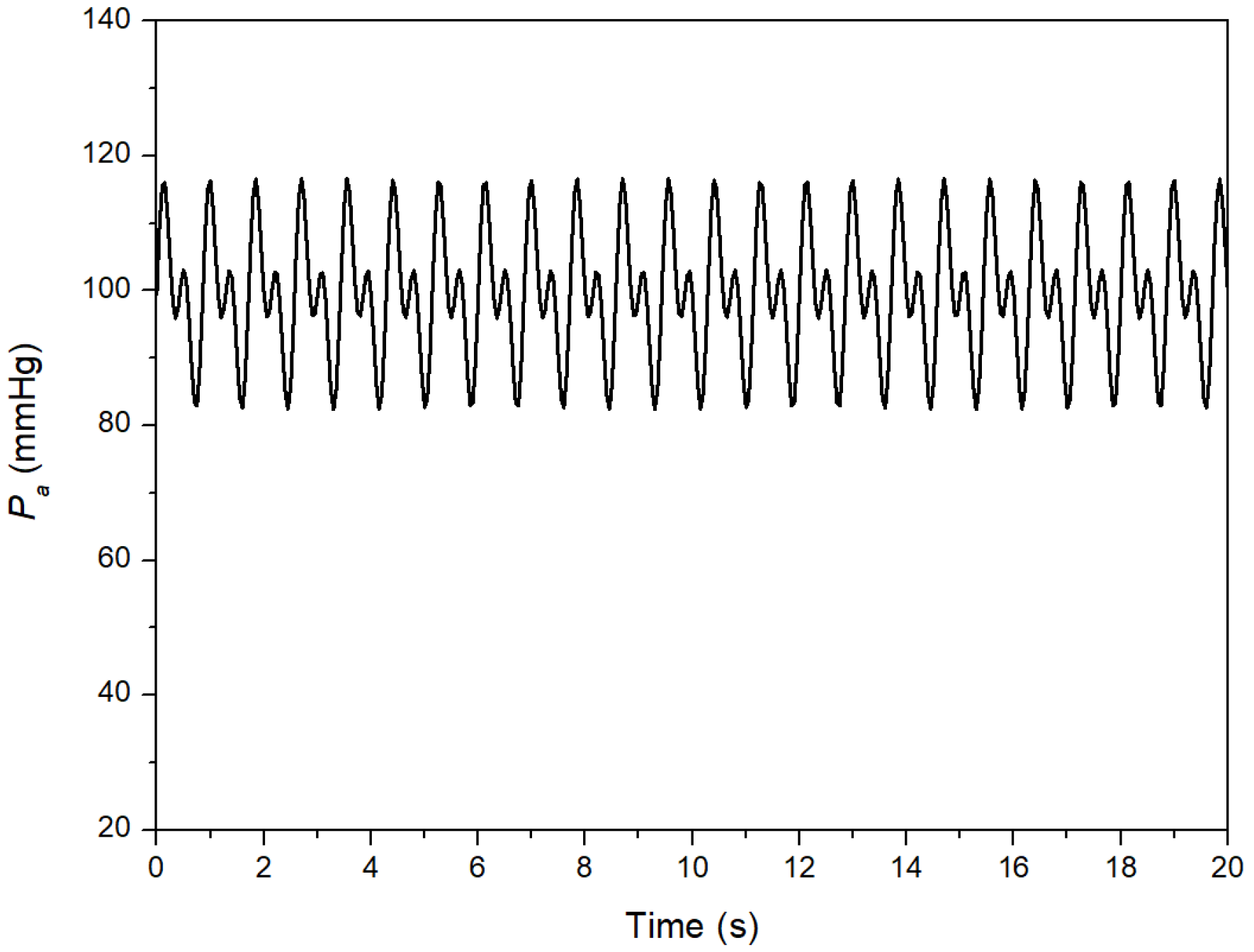

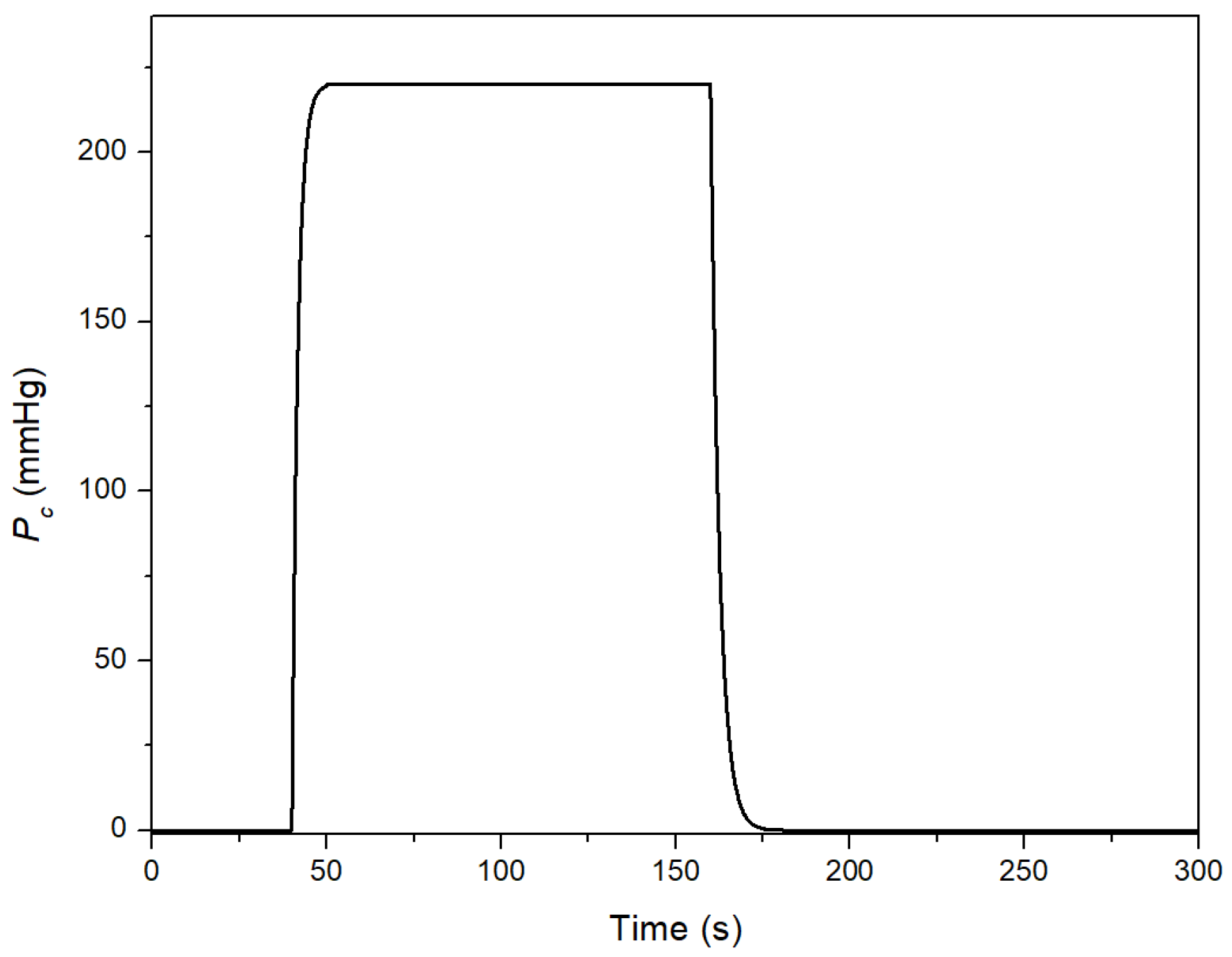

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Clinical Data

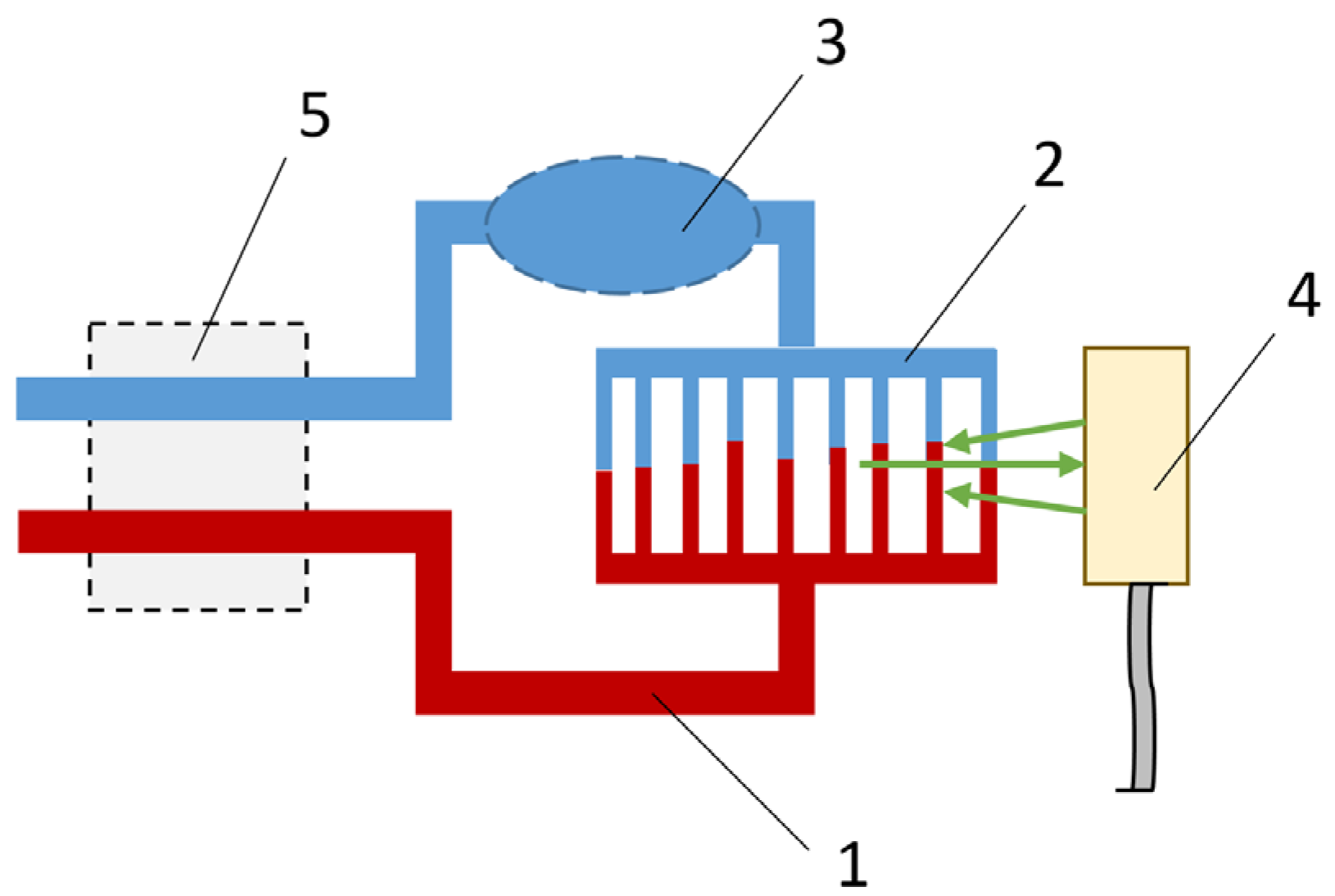

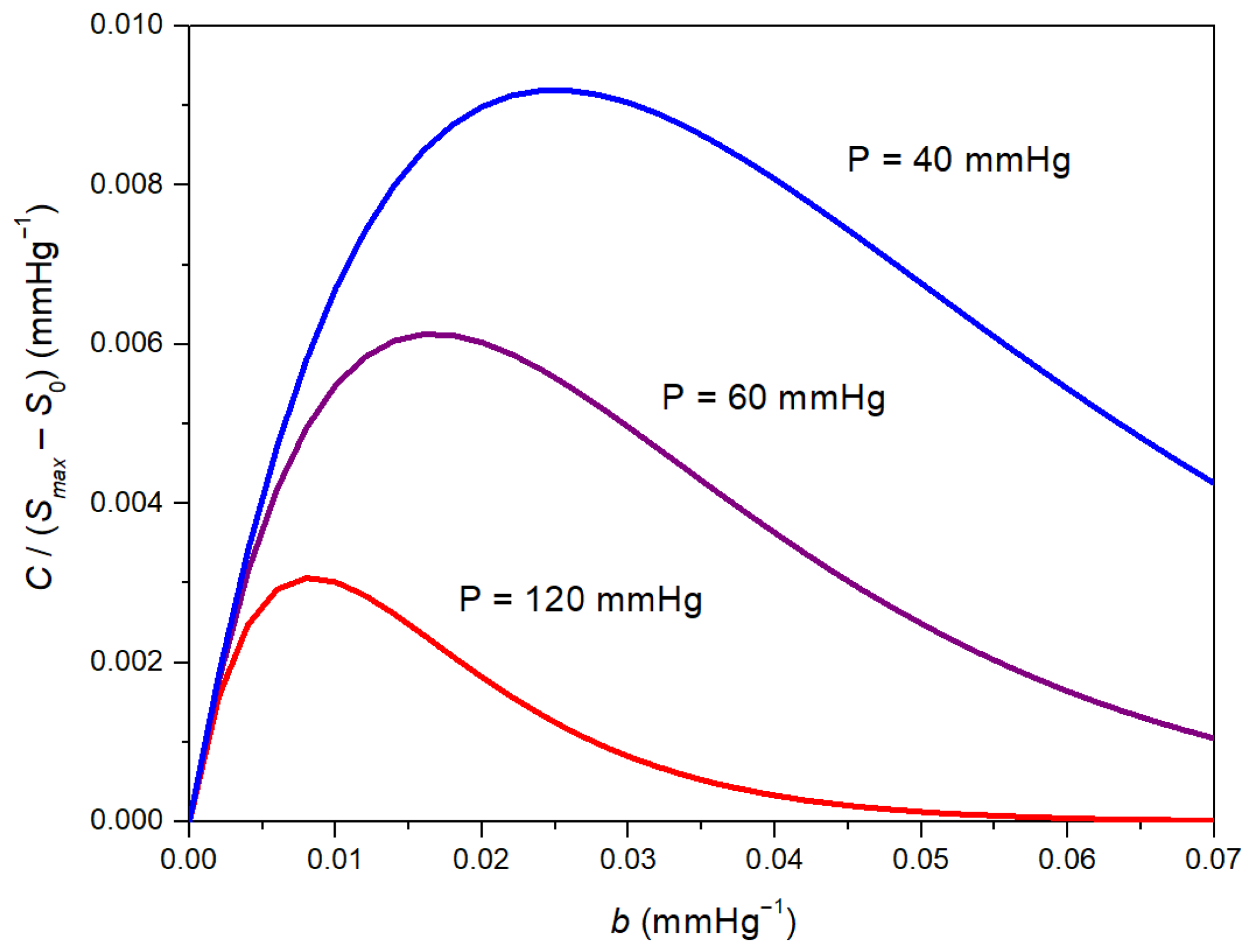

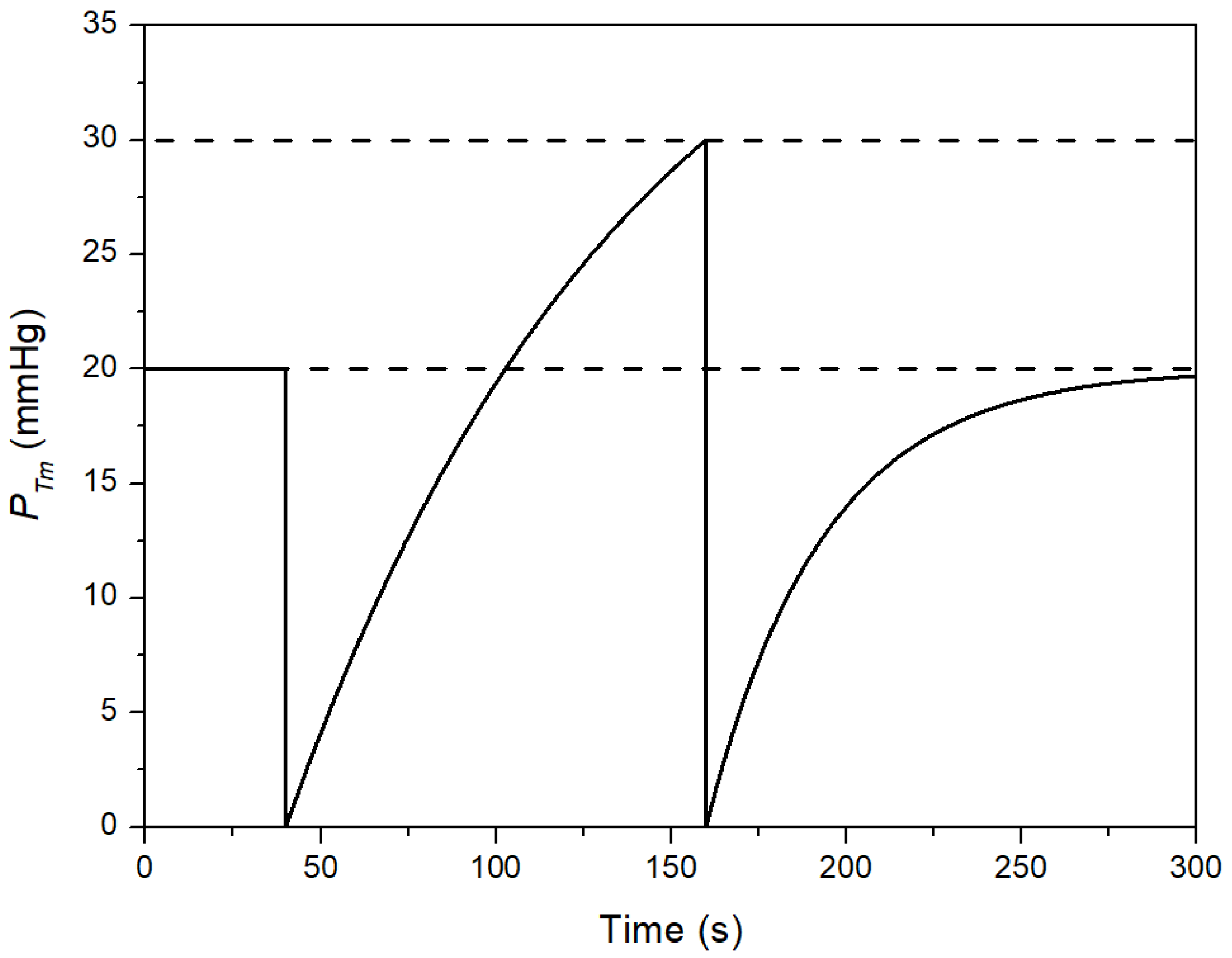

2.2. Theoretical Approach

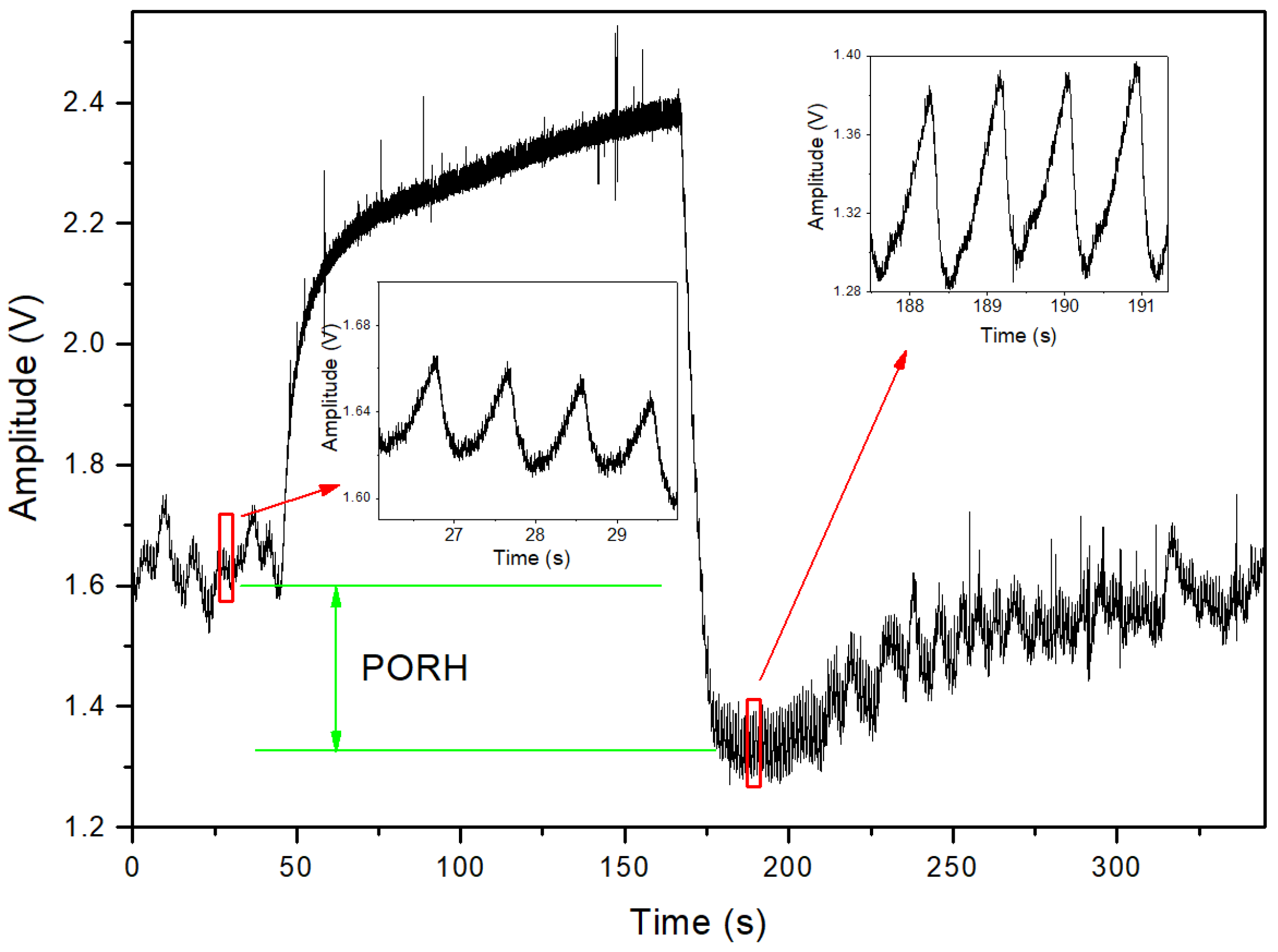

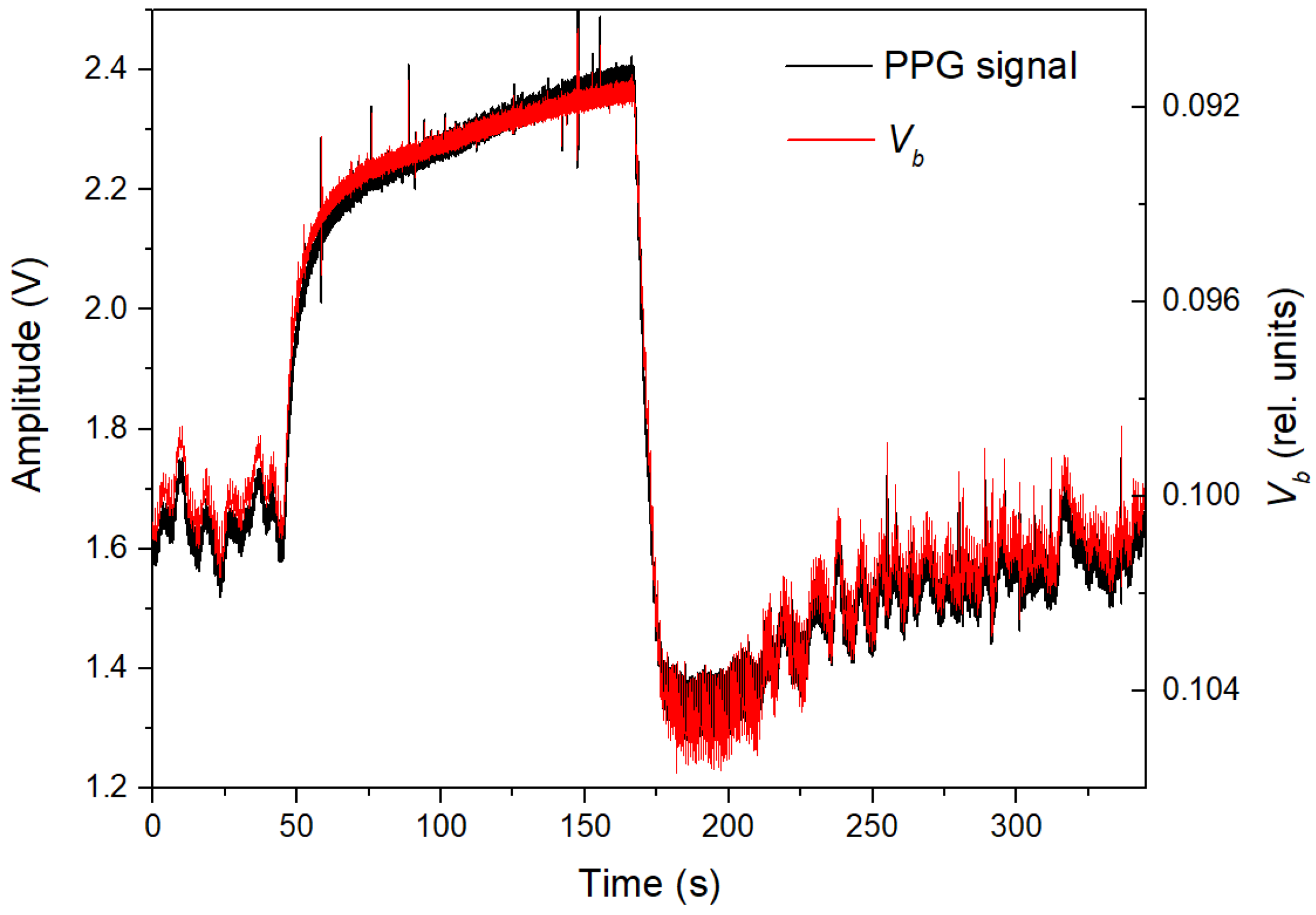

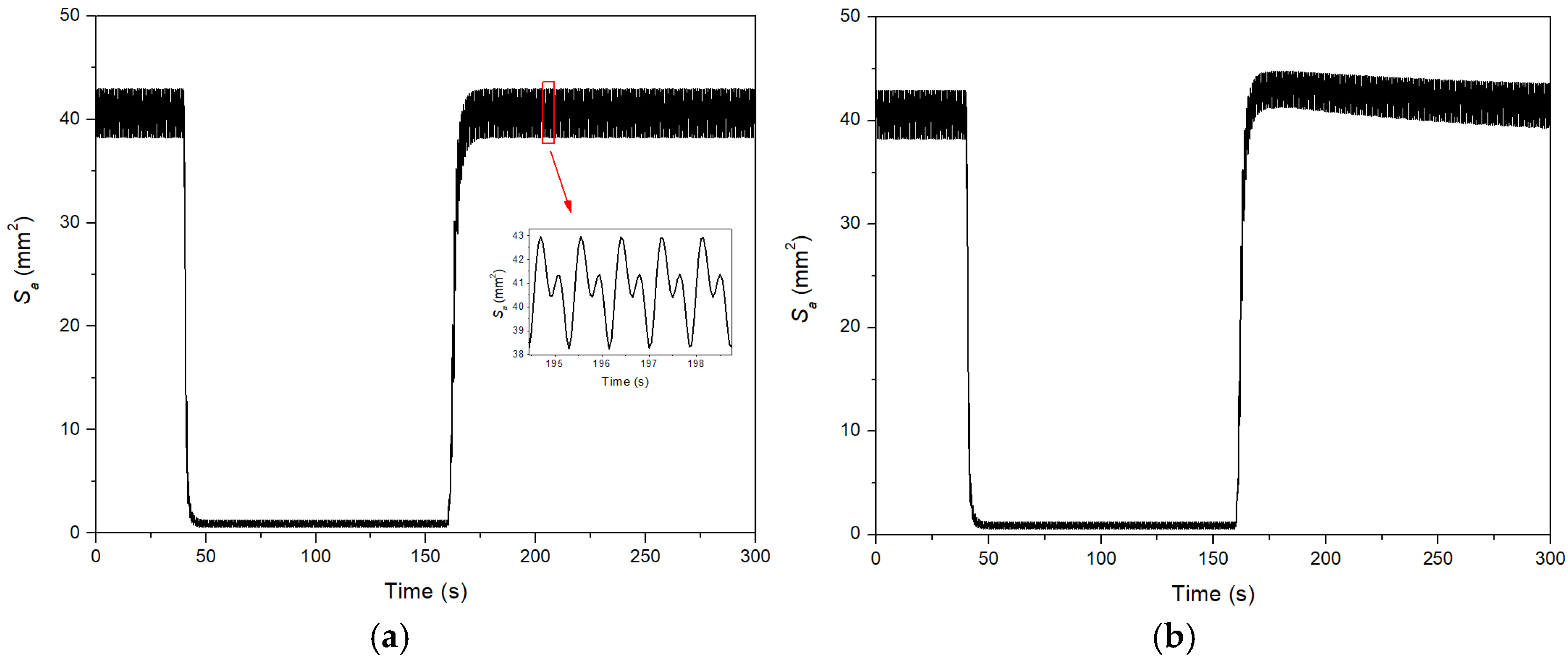

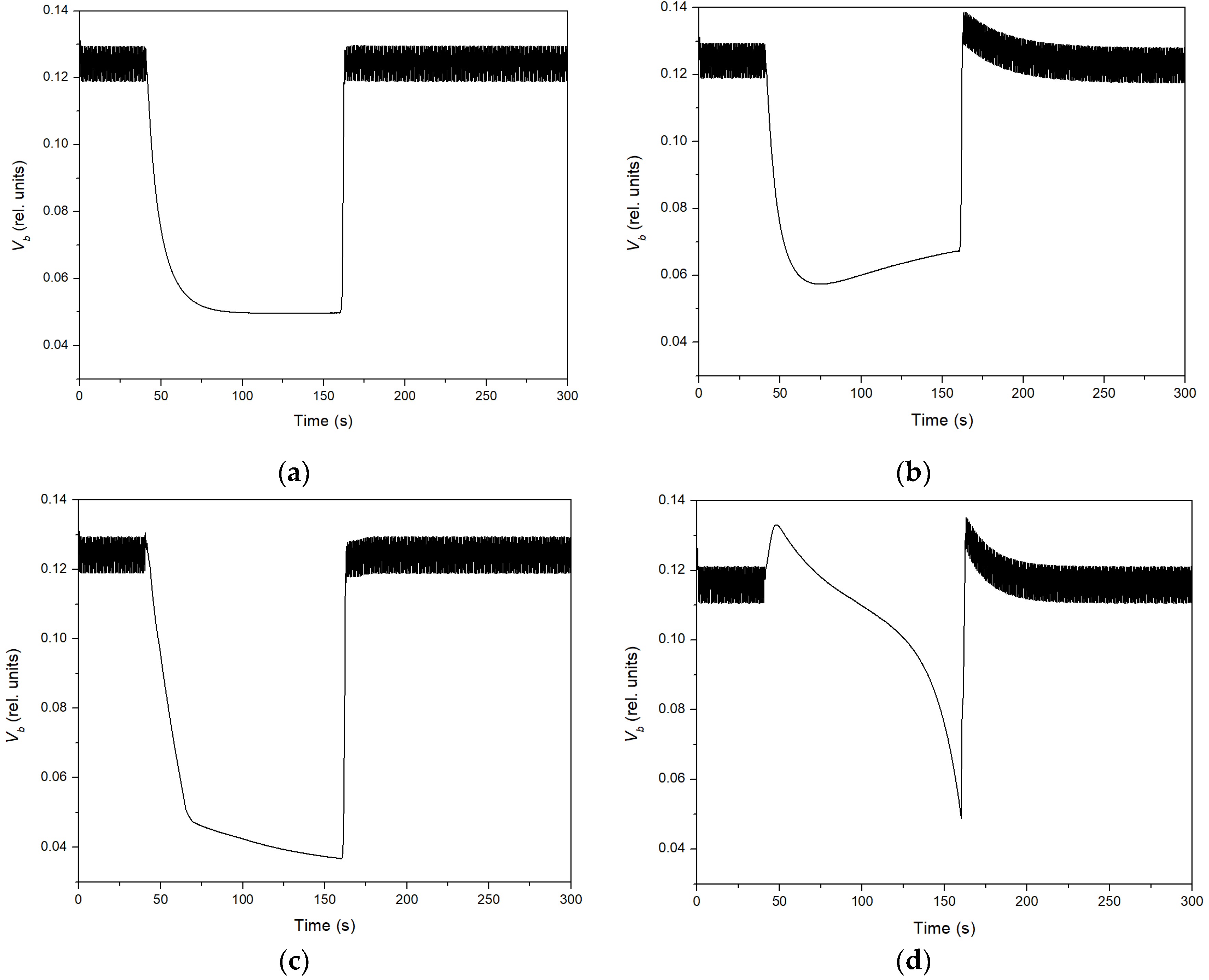

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Roth, G.A.; Mensah, G.A.; Johnson, C.O.; Addolorato, G.; Ammirati, E.; Baddour, L.M.; Barengo, N.C.; Beaton, A.Z.; Benjamin, E.J.; Benziger, C.P.; et al. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risk factors, 1990–2019: Update from the GBD 2019 study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 76, 2982–3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luzhnov, P.V.; Pika, T.O.; Shamaev, D.M. Developing the structure of a hardware and software system for quantitative diagnosis of microhemodynamics. Int. J. Biomed. 2015, 5, 228–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, V.; Varghese, B.; van Leeuwen, T.G.; Steenbergen, W. Review of methodological developments in laser Doppler flowmetry. Lasers Med. Sci. 2009, 24, 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriacou, P.A.; Allen, J. Photoplethysmography: Technology, Signal Analysis and Applications; Elsevier Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lapitan, D.; Rogatkin, D. Optical incoherent technique for noninvasive assessment of blood flow in tissues: Theoretical model and experimental study. J. Biophotonics 2021, 14, e202000459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdes, C.P.; Varma, H.M.; Kristoffersen, A.K.; Dragojevic, T.; Culver, J.P.; Durduran, T. Speckle contrast optical spectroscopy, a non-invasive, diffuse optical method for measuring microvascular blood flow in tissue. Biomed. Opt. Express 2014, 5, 2769–2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roustit, M.; Cracowski, J.L. Non-invasive assessment of skin microvascular function in humans: An insight into methods. Microcirculation 2012, 19, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troy, A.M.; Cheng, H.M. Human microvascular reactivity: A review of vasomodulating stimuli and non-invasive imaging assessment. Physiol. Meas. 2021, 42, 094001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roustit, M.; Cracowski, J.L. Assessment of endothelial and neurovascular function in human skin microcirculation. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2013, 34, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogatkin, D.A.; Ivlieva, A.L.; Shtyflyuk, M.E. Cumulative assessment of tone and reactivity of the microvascular bed based on in vivo optical flowmetry data. Justification of the approach. Med. Fiz. 2024, 3, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, P.S. Oscillometric measurement of blood pressure: A simplified explanation. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2019, 33, 349–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharman, J.E.; Tan, I.; Stergiou, G.S.; Lombardi, C.; Saladini, F.; Butlin, M.; Padwal, R.; Asayama, K.; Avolio, A.; Brady, T.M.; et al. Automated ‘oscillometric’ blood pressure measuring devices: How they work and what they measure. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2023, 37, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forouzanfar, M.; Dajani, H.R.; Groza, V.Z.; Bolic, M.; Rajan, S.; Batkin, I. Oscillometric blood pressure estimation: Past, present, and future. IEEE Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2015, 8, 44–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Yadav, S.; Kumar, A. Accuracy of oscillometric-based blood pressure monitoring devices: Impact of pulse volume, arrhythmia, and respiratory artifact. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2024, 38, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, F.K.; Turney, D. Oscillometric determination of diastolic, mean and systolic blood pressure—A numerical model. J. Biomech. Eng. 1986, 108, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drzewiecki, G.; Hood, R.; Apple, H. Theory of the oscillometric maximum and the systolic and diastolic detection ratios. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 1994, 22, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forouzanfar, M.; Ahmad, S.; Batkin, I.; Dajani, H.R.; Groza, V.Z.; Bolic, M. Coefficient-free blood pressure estimation based on pulse transit time–cuff pressure dependence. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2013, 60, 1814–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Reynolds, L.; Alberts, T.; Vahala, L.; Hao, Z. Model-based analysis of arterial pulse signals for tracking changes in arterial wall parameters: A pilot study. Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol. 2019, 18, 1629–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raamat, R.; Talts, J.; Jagomägi, K.; Länsimies, E. Mathematical modelling of non-invasive oscillometric finger mean blood pressure measurement by maximum oscillation criterion. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 1999, 37, 784–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babbs, C.F. Oscillometric measurement of systolic and diastolic blood pressures validated in a physiologic mathematical model. Biomed. Eng. Online 2012, 11, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbé, K.; Van Moer, W.; Schoors, D. Analyzing the windkessel model as a potential candidate for correcting oscillometric blood-pressure measurements. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2012, 61, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriacou, P.A.; Shafqat, K.; Pal, S.K. Pilot investigation of photoplethysmographic signals and blood oxygen saturation values during blood pressure cuff-induced hypoperfusion. Measurement 2009, 42, 1001–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitzan, M.; Slotki, I.; Shavit, L. More accurate systolic blood pressure measurement is required for improved hypertension management: A perspective. Med. Devices 2017, 10, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Xiong, J.; He, L. Fair non-contact blood pressure estimation using imaging photoplethysmography. Biomed. Opt. Express 2024, 15, 2133–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, S.A.; Rogowski, Z.; Kanter, Y.; Hemli, J. DC photoplethysmography in the evaluation of sympathetic vasomotor responses. Clin. Physiol. 1993, 13, 561–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashayekhi, G.; Zahedi, E.; Attar, H.M.; Sharifi, F. Flow mediated dilation with photoplethysmography as a substitute for ultrasonic imaging. Physiol. Meas. 2015, 36, 1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapitan, D.G.; Rogatkin, D.A. Features of the DC component of the laser Doppler signal during arterial occlusion. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference Laser Optics (ICLO), Saint Petersburg, Russia, 4–8 June 2018; p. 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapitan, D.G.; Raznitsyn, O.A. A method and a device prototype for noninvasive measurements of blood perfusion in a tissue. Instrum. Exp. Tech. 2018, 61, 745–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glazkov, A.A.; Lapitan, D.G.; Makarov, V.V.; Rogatkin, D.A. Optical non-invasive automated device for the study of central and peripheral hemodynamics. Phys. Bases Instrum. 2021, 10, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapitan, D.G.; Tarasov, A.P.; Rogatkin, D.A. Justification of the photoplethysmography sensor configuration by Monte Carlo modeling of the pulse waveform. J. Biomed. Photonics Eng. 2022, 8, 030306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasov, A.P.; Rogatkin, D.A. Modeling of pulse wave signals for a blood pressure monitor with a remote photoplethysmography sensor. In Proceedings of the 2025 Photonics & Electromagnetics Research Symposium (PIERS), Chiba, Japan, 5–9 November 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Saeed, F.; Carter, C.; Kolade, J.; Brothers, R.M.; Liu, H. Understanding metabolic responses to forearm arterial occlusion measured with two-channel broadband near-infrared spectroscopy. J. Biomed. Opt. 2024, 29, 117001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, B.; Chase, J.; Nokes, R.; Shaw, G.; Wake, G. Minimal haemodynamic system model including ventricular interaction and valve dynamics. Med. Eng. Phys. 2004, 26, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caro, C.G.; Pedley, T.J.; Schroter, R.C.; Seed, W.A.; Parker, K.H. The Mechanics of the Circulation; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Volobuev, A.N. Fluid flow in tubes with elastic walls. Phys.-Uspekhi 1995, 38, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, D.J.; Babbs, C.F.; Geddes, L.A.; Bourland, J.D. Measurements of young’s modulus of elasticity of the canine aorta with ultrasound. Ultrason. Imaging 1979, 1, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, H.H.; Collins, R.E. On the pressure-volume relationship in circulatory elements. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 1982, 20, 565–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, J.E.; Guyton, A.C. Textbook of Medical Physiology, 13th ed.; Elsevier Science: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lan, H.; Al-Jumaily, A.M.; Lowe, A.; Hing, W. Effect of tissue mechanical properties on cuff-based blood pressure measurements. Med. Eng. Phys. 2011, 33, 1287–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forouzanfar, M.; Dajani, H.R.; Groza, V.Z.; Bolic, M.; Rajan, S.; Batkin, I. Ratio-independent blood pressure estimation by modeling the oscillometric waveform envelope. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2014, 63, 2501–2503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekhar, A.; Yavarimanesh, M.; Hahn, J.O.; Sung, S.H.; Chen, C.H.; Cheng, H.M.; Mukkamala, R. Formulas to explain popular oscillometric blood pressure estimation algorithms. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tarasov, A.P.; Karpov, V.N.; Rogatkin, D.A. Evaluation Model of Microhemodynamics in Finger Skin at Arterial Occlusion and Post-Occlusive Hyperemia. Fluids 2025, 10, 314. https://doi.org/10.3390/fluids10120314

Tarasov AP, Karpov VN, Rogatkin DA. Evaluation Model of Microhemodynamics in Finger Skin at Arterial Occlusion and Post-Occlusive Hyperemia. Fluids. 2025; 10(12):314. https://doi.org/10.3390/fluids10120314

Chicago/Turabian StyleTarasov, Andrey P., Vasily N. Karpov, and Dmitry A. Rogatkin. 2025. "Evaluation Model of Microhemodynamics in Finger Skin at Arterial Occlusion and Post-Occlusive Hyperemia" Fluids 10, no. 12: 314. https://doi.org/10.3390/fluids10120314

APA StyleTarasov, A. P., Karpov, V. N., & Rogatkin, D. A. (2025). Evaluation Model of Microhemodynamics in Finger Skin at Arterial Occlusion and Post-Occlusive Hyperemia. Fluids, 10(12), 314. https://doi.org/10.3390/fluids10120314