Preparation of Gel Electrolyte for Lithium Metal Solid-State Batteries and Its Failure Behavior at Different Temperatures

Abstract

1. Introduction

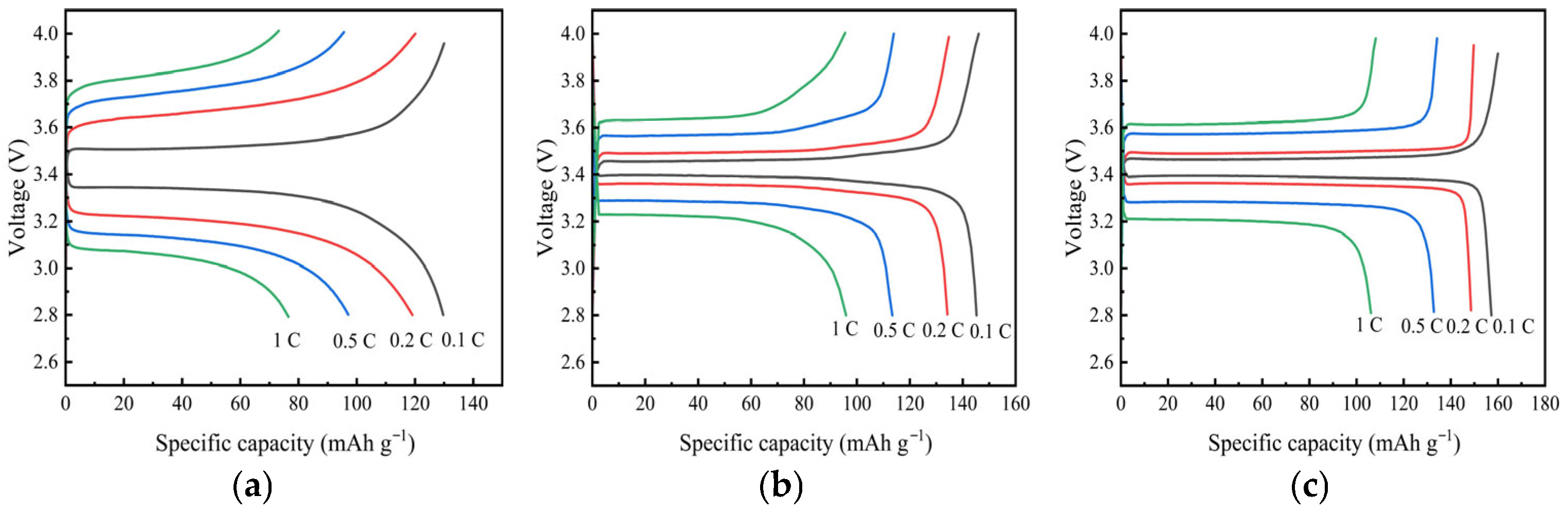

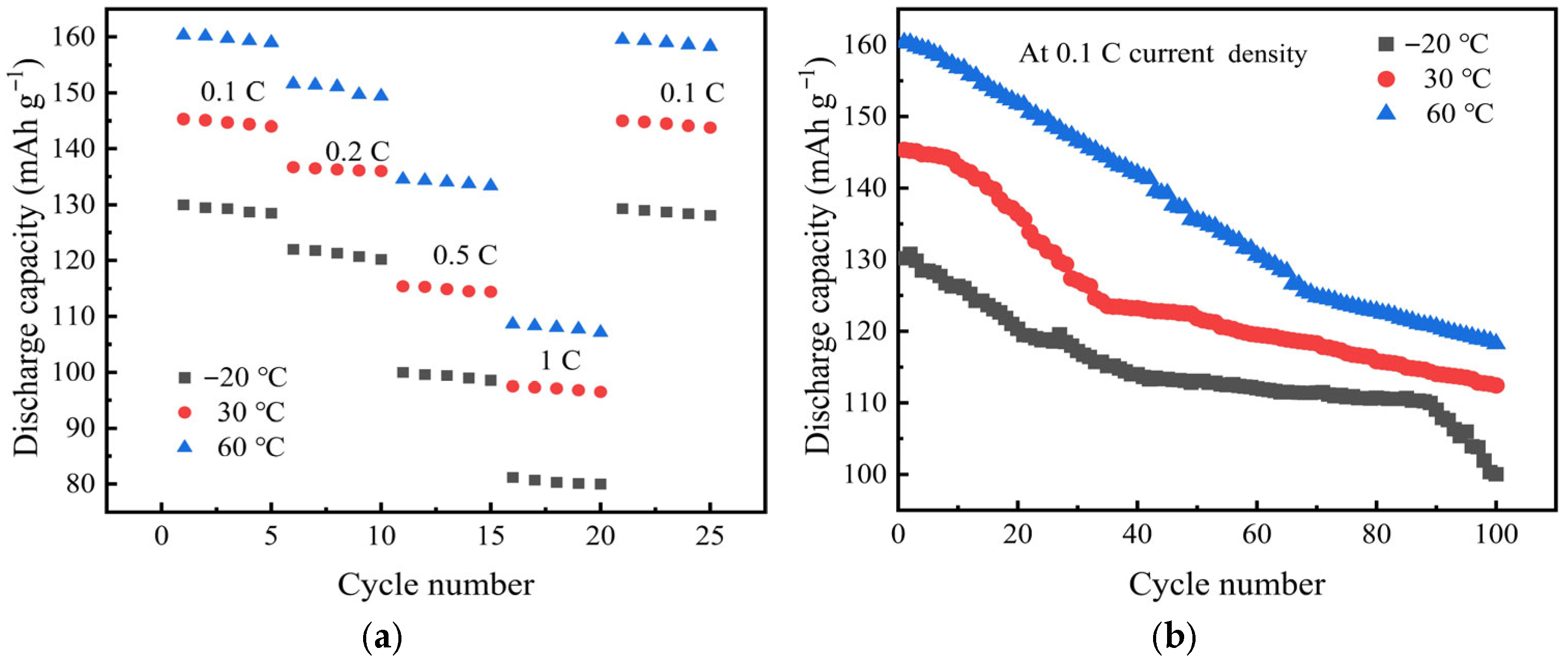

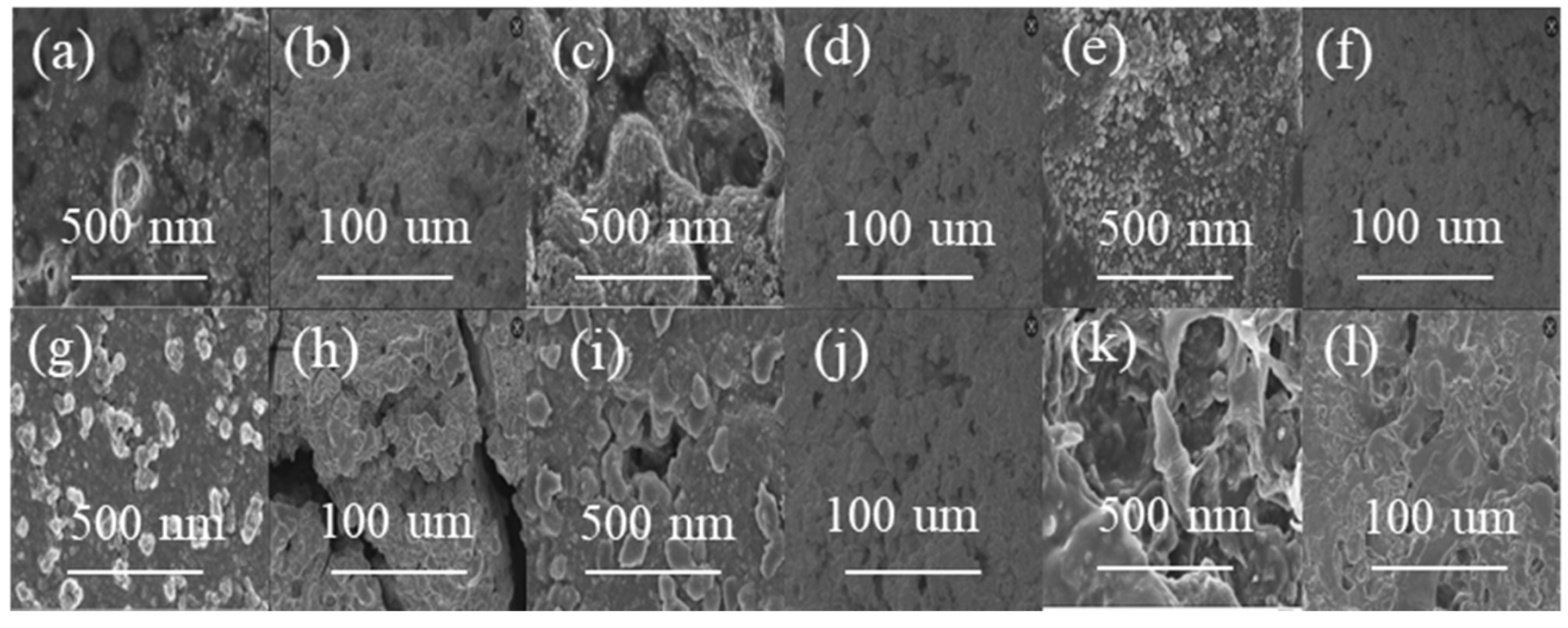

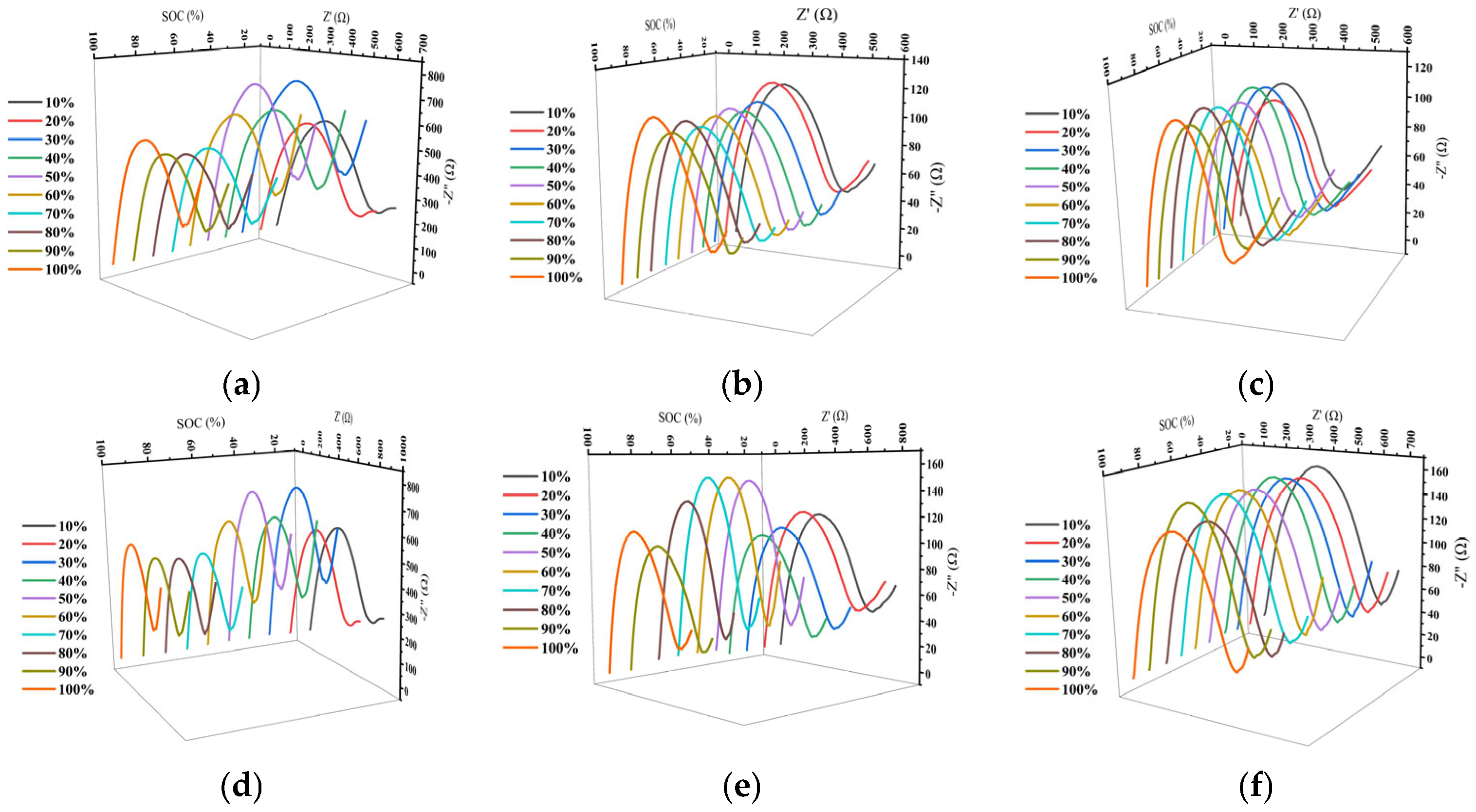

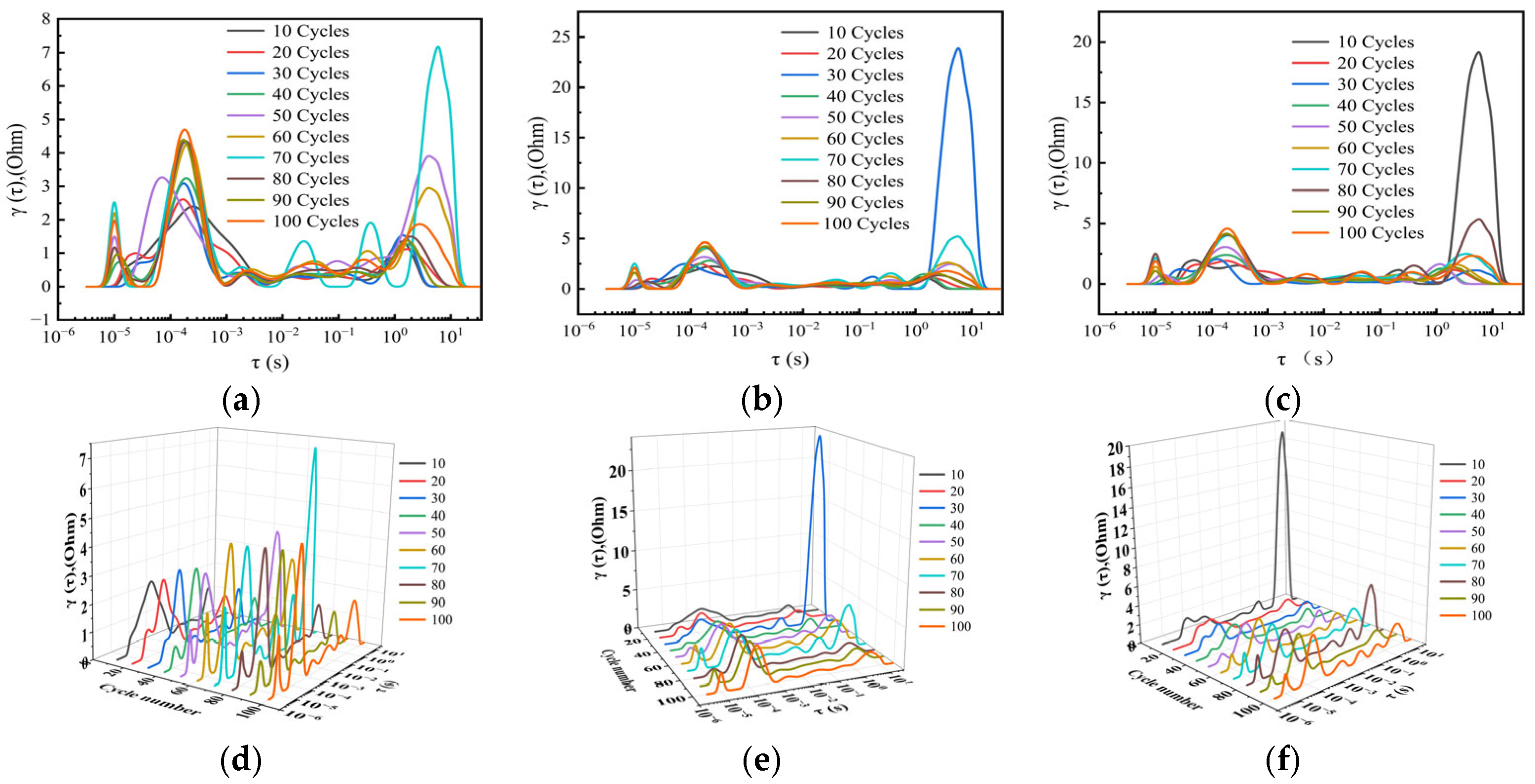

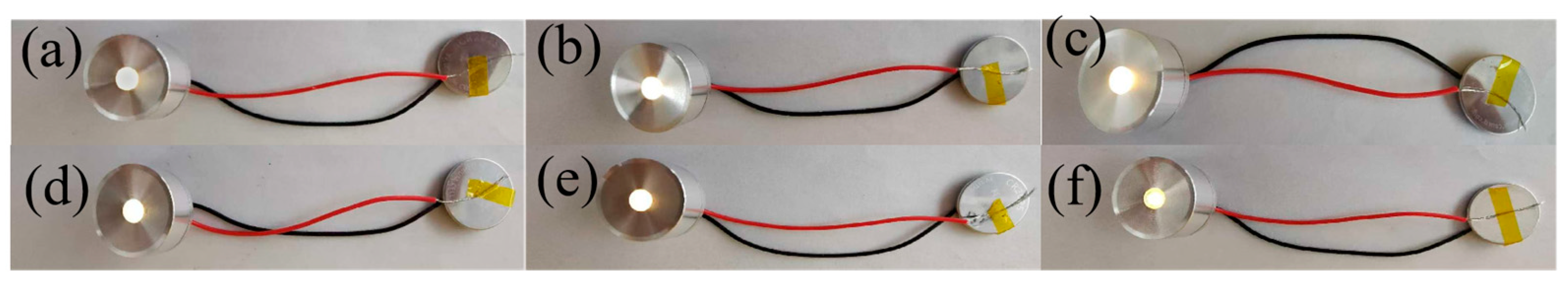

2. Results and Discussion

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

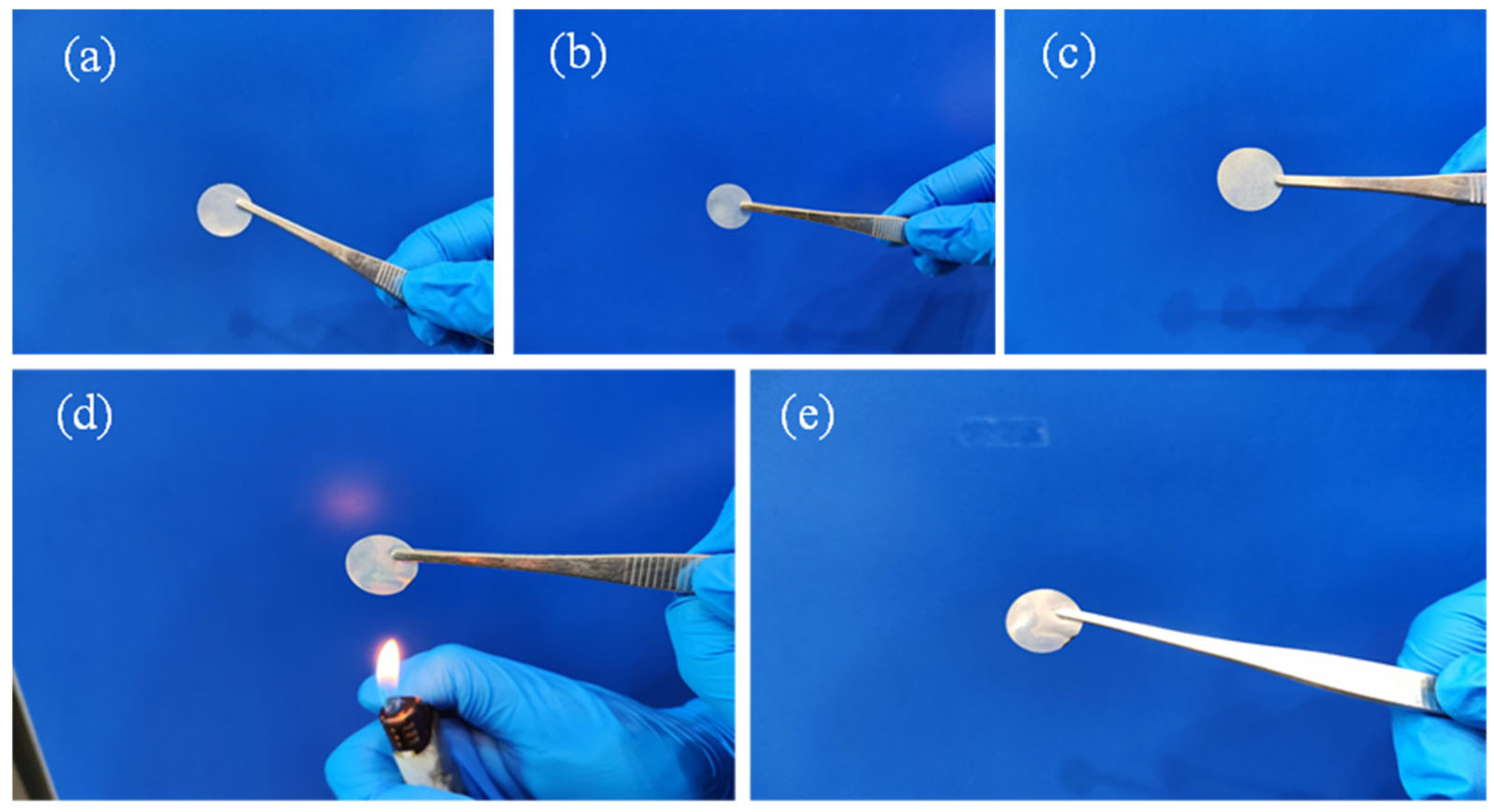

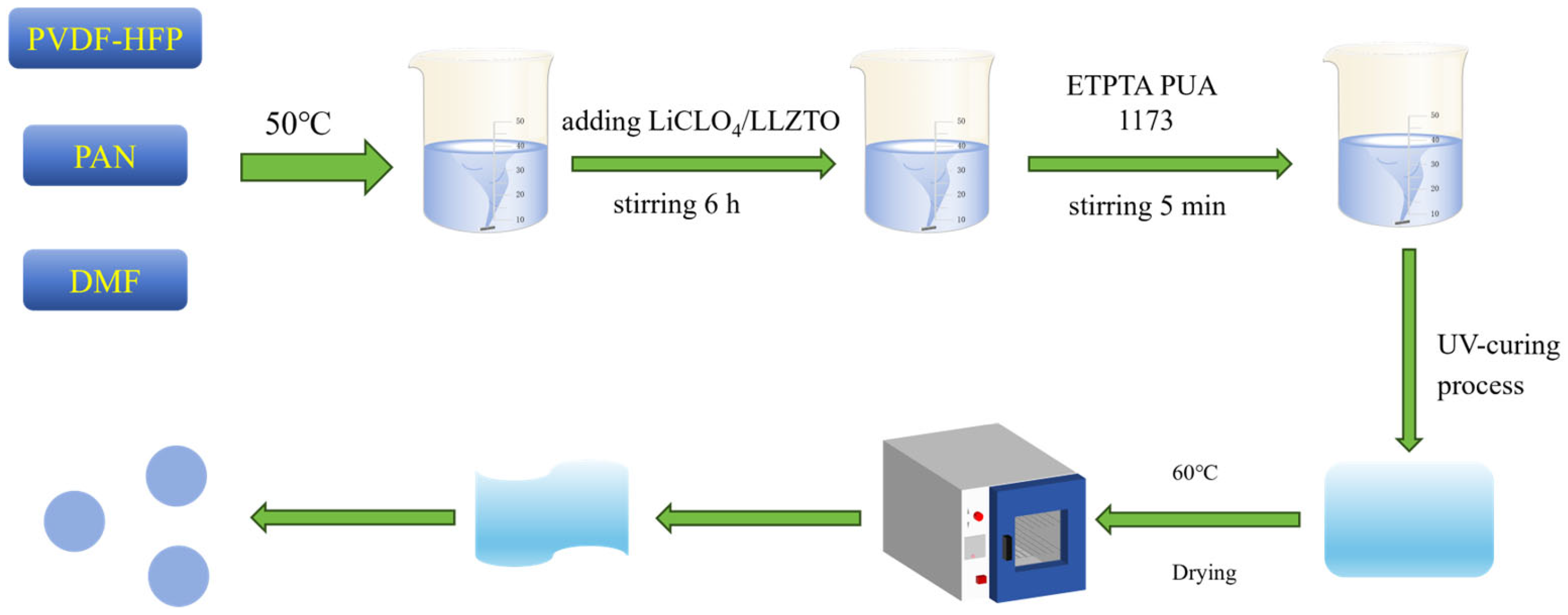

4.1. Preparation of Gel Polymer Electrolytes

4.2. Characterization and Test Methods of Gel Polymer Electrolytes

4.3. Preparation of Electrodes

4.4. Electrochemical Performance Test

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gallus, D.R.; Wagner, R.; Streipert, B.; Kraft, V.; Weber, W.; Kloepsch, R.; Wiemersmeyer, S.; Cekiclaskovic, I.; Winter, M. New Insights into Structure-Property-Relationship of High-Voltage Electrolyte Components for Lithium-Ion Batteries Using a pka Value Approach. ECS Meet. Abstr. 2015, 184, 410–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, C.H.; Karkar, Z.; Houache, M.S.E.; Kim, D.; Jang, B.; Abu-Lebdeh, Y. Enabling 5V Solid-State Lithium Metal Batteries Using Catholyte for LiNi0.5Mn1.5O4 Spinel. Meet. Abstr. 2024, MA2024-02, 920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, A.; Fazeli, A. Future Market and Challenges of Lithium/Sulfur Batteries; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez, M.; Fernández-Cardador, A.; Fernández-Rodríguez, A.; Cucala, A.P.; Pecharromán, R.R.; Sánchez, P.U.; Cortázar, I.V. Review on the use of energy storage systems in railway applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 207, 114904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgelall, R. Solid-State Battery Developments: A Cross-Sectional Patent Analysis. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Fang, Z.; Li, Z.; Xu, W.; Wang, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, W.; Zhao, D.; Guo, X. Porous Co3O4 materials prepared by solid-state thermolysis of a novel Co-MOF crystal and their superior energy storage performances for supercapacitors. J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 1, 7235–7241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blejan, D.; Muresan, L.M. Corrosion behavior of ZnNiAl2O3 nanocomposite coatings obtained by electrodeposition from alkaline electrolytes. Mater. Corros. 2014, 64, 433–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, P.; Yang, Z.; Wang, L.; Li, Z.; Liu, C.; Liu, B.; Sun, Z.; Pei, H.; Lv, Z. Lignin Derived Ultrathin All-Solid Polymer Electrolytes with 3D Single-Ion Nanofiber Ionic Bridge Framework for High Performance Lithium Batteries. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2400970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, K.; Park, J.; Appiah, P.; Song, S.W.; Oh, T. Rapid Experimental Optimization of Liquid Electrolytes Compositions for Safe Li-Ion Battery with Outstanding Long-Term Performance: Multi-Objective Constrained Bayesian Optimization Approach. Meet. Abstr. 2024, MA2024-02, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandara, T.M.W.J.; Gunathilake, S.M.S.; Gamachchi, G.G.D.M.; Pemasiri, B.M.K.; Desilva, L.A.; Dissanayake, M.A.K.L.; Kumara, G.R.A. Strategic graphene integration in multilayer photoanodes for enhanced quasi-solid-state dye-sensitized solar cells and performance under variable irradiance. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2025, 55, 691–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, B.; Xiao, X.; Xu, G. 40 °C–60 °C useable transparent hydrogel electrolyte for flexible and tailorable electrochromic devices with excellent performance. Mater. Today Chem. 2023, 33, 101703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirunavukarasu, G.; Kundu, S.; Mishra, B.; Chatterjee, S. Effect of Bonding Temperature on Interfacial Reaction and Mechanical Properties of Diffusion-Bonded Joint Between Ti-6Al-4V and 304 Stainless Steel Using Nickel as an Intermediate Material. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2014, 45, 2067–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, S.K.; Kundu, B.; Mahato, A.; Thakur, N.L.; Joardar, S.N.; Mandal, B.B. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of the marine sponge skeleton as a bone mimicking biomaterial. Integr. Biol. Quant. Biosci. Nano Macro 2015, 7, 250–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kundu, D.; Katre, V.; Dhillon, K.; Deshpande, M.; Parmar, M. Innovative social protection mechanism for alleviating catastrophic expenses on multidrug-resistant tuberculosis patients in Chhattisgarh, India. WHO South-East Asia J. Public Health 2015, 4, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rana, A.K.; Kundu, S.; Datta, S. An investigation of prototype development using 3D printer: A digital fabrication approach. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2024, 2856, 012014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bag, S.; Choutipalli, V.S.K.; Bhadra, A.; Shuford, K.L.; Kundu, D.; Raj, C.R. Carbothermal reduction-induced oxygen vacancies in spinel cathodes for high-performance aqueous zinc-ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A Mater. Energy Sustain. 2024, 12, 22998–23007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhadra, A.; Kundu, D. Stabilizing the High-Voltage Aqueous Battery Chemistry of LiMn2O4. Meet. Abstr. 2024, MA2024-01, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhadra, A.; Brunisholz, M.; Bonsu, J.O.; Kundu, D. Carbon Mediated In Situ Cathode Interface Stabilization for High Rate and Highly Stable Operation of All-Solid-State Lithium Batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2025, 15, 2403608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonsu, J.O.; Bhadra, A.; Kundu, D. Wet Chemistry Route to Li3InCl6: Microstructural Control Render High Ionic Conductivity and Enhanced All-Solid-State Battery Performance. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2403208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhadra, A.; Kundu, A.; Raj, C.R. Surface-engineered mesoporous carbon-based material for the electrochemical detection of hexavalent chromium. J. Chem. Sci. 2021, 133, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darkwah, W.; Appiagyei, A.B.; Puplampu, J.; Bonsu, J.O. Mechanistic Understanding of the Use of Single-Atom and Nanocluster Catalysts for Syngas Production via Partial Oxidation of Methane. Langmuir ACS J. Surf. Colloids 2023, 39, 8568–8588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appiagyei, A.B.; Anang, D.A.; Bonsu, J.O.; Asiedua-Ahenkorah, L.; Mane, S.D.; Kim, H.S.; Bathula, C. Sucrose-directed porous carbon interfaced α-Fe2O3-rGO for supercapacitors. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2023, 936, 117383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appiagyei, A.B.; Bonsu, J.O.; Han, J.I. Robust structural stability and performance -e nhanced asymmetric supercapacitors based on CuMoO4/ZnMoO4 nanoflowers prepared via a simple and low-energy precipitation route. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2021, 32, 6668–6681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonsu, J.O.; Appiagyei, A.B.; Han, J.I. Induced symmetric 2D Mesoporous Graphitic Carbon Spinel Cobalt Ferrite (CoFe2O4/2D-C) with high porosity fabricated via a facile and swift sucrose templated microwave combustion route for an improved supercapacitive performance. Mater. Res. Bull. 2020, 133, 111053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, G.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, Y.; Gao, C.; Ma, H.; Yang, Z.; Jing, Y.; Tu, H. A novel coarse-grained discrete element method for simulating failure process of strongly bonded particle materials. Powder Technol. 2025, 464, 121212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Tang, G.; Li, H.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, J.; Luo, Y.; Yue, J.; Shi, Y.; Chen, Z. Low-temperature fabrication of NASICON-type LATP with superior ionic conductivity. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 36961–36967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Sun, Z.; Sun, C.; Li, F.; Chen, K.; Zhang, Z.; Hou, G.; Cheng, H.M.; Li, F. Homogeneous and fast ion conduction of PEO-based solid-state electrolyte at low temperature. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 2007172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadanaga, K.; Takano, R.; Ichinose, T.; Mori, S.; Hayashi, A.; Tatsumisago, M. Low temperature synthesis of highly ion conductive Li7La3Zr2O12–Li3BO3 composites. Electrochem. Commun. 2013, 33, 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Jing, M.; Wang, L.; Xu, H.; Yan, X.; He, X. PDOL-based solid electrolyte toward practical application: Opportunities and challenges. Nano-Micro Lett. 2024, 16, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Liu, Z.; Akbar, M.; Gao, C.; Dong, W.; Meng, Y.; Jin, X.; Xia, C.; Wang, B.; Zhu, B. Efficiently enhance the proton conductivity of YSZ-based electrolyte for low temperature solid oxide fuel cell. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 5637–5645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tron, A.; Nosenko, A.; Park, Y.D.; Mun, J. Enhanced ionic conductivity of the solid electrolyte for lithium-ion batteries. J. Solid State Chem. 2018, 258, 467–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Ren, X.; Zhou, W.; Xie, G.; Zhang, G. Thermal stability and thermal conductivity of solid electrolytes. APL Mater. 2022, 10, 040902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Suzuki, K.; Yonemura, M.; Hirayama, M.; Kanno, R. Enhancing fast lithium ion conduction in Li4GeO4–Li3PO4 solid electrolytes. ACS Appl. Energ. Mater. 2019, 2, 6608–6615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinasamy, S. Investigation on the Performance of Tetraglyme-Based Solid Copolymer Electrolytes for Solid-State Electrical Double Layer Capacitors (Edlcs). Ph.D. Thesis, University of Malaya (Malaysia), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Iwata-Yoshikawa, N.; Okamura, T.; Shimizu, Y.; Hasegawa, H.; Takeda, M.; Nagata, N. TMPRSS2 Contributes to Virus Spread and Immunopathology in the Airways of Murine Models after Coronavirus Infection. J. Virol. 2019, 93, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pakizeh, E.; Moradi, M.; Ahmadi, A. Effect of sol–gel pH on XRD peak broadening, lattice strain, ferroelectric domain orientation, and optical bandgap of nanocrystalline Pb1. 1 (Zr0.52Ti0.48)O3. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2014, 75, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aversa, T.; Lombardo, F.; Corrias, A.; Salerno, M.; De Luca, F.; Wasniewska, M. In young patients with Turner or Down syndrome, Graves’ disease presentation is often preceded by Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Thyroid Off. J. Am. Thyroid Assoc. 2014, 24, 744–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hincapie, D.; Tedrow, U.B.; Miranda-Arboleda, A.F.; Koplan, B.A.; Gordon, J.S.; Sutter, J.S.; Londono, G.A.; Shadrin, I.; Ezzeddine, F.; Cha, Y.M. Cardiac resynchronization therapy with left bundle branch area pacing in patients with a definitive diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis. Europace 2025, 27, euaf085-612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Dai, Z.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Li, Z.; Wang, L.; Gao, X.; Qiu, Q.; Qiu, X.; Liu, Z. Development of a machine learning-based predictive risk model combining fatty acid metabolism and ferroptosis for immunotherapy response and prognosis in prostate cancer. Discov. Oncol. 2025, 16, 744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.; Yan, Y.; Yuan, C.; Huang, B.; Yang, C.; Ma, J.; Wang, J.; Huo, L.; Cui, Z.; Wang, X. Making Fe-Si-B amorphous powders as an effective catalyst for dye degradation by high-energy ultrasonic vibration. Mater. Des. 2020, 194, 108876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.H.; Yang, S.S.; Park, M.H.; Han, S.; Kim, H. Design of an Improved Algorithm for VR-Based Image Processing. In Advances in Computer Science and Ubiquitous Computing; Springer: Singapore, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Z.; Tang, Z.; Jiang, L.; Ma, G. A referenceless image degradation perception method based on the underwater imaging model. Appl. Intell. 2022, 52, 6522–6538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, N.; Bontemps, S.; Motte, F.; Ossenkopf, V.; Federrath, C. Understanding star formation in molecular clouds III. Probability distribution functions of molecular lines in Cygnus X. Astron. Astrophys. 2015, 587, A74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keruckiene, R.; Vaitusionak, A.A.; Hulnik, M.I.; Berezianko, I.A.; Gudeika, D.; Macionis, S.; Mahmoudi, M.; Volyniuk, D.; Valverde, D.; Olivier, Y. Is a small singlet–triplet energy gap a guarantee of TADF performance in MR-TADF compounds? Impact of the triplet manifold energy splitting. J. Mater. Chem. C Mater. Opt. Electron. Devices 2024, 12, 3450–3464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Das, S.; Sepay, N.; Basak, N.; Sen, B.; Islam, E.; Smaalen, S.V.; Ali, S.I. Order–Disorder Structure in Ni3Sb4CO6F6: Synthesis, Characterization, and Its Applications toward Photocatalytic Dye Degradation and Antibacterial Activities. Cryst. Growth Des. 2024, 24, 9110–9125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhtiar, S.U.H.; Ai, P.; Sattar, H.; Ali, S.; Al-Fatesh, A.S.; Zhao, J.; Wen, D.; Fu, Q. Harnessing point-defect induced local symmetry breaking in a tetragonal-HfO2 system through sterically mismatched ion doping. J. Mater. Chem. C 2024, 12, 2933–2943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenderovich, I.G.; Denisov, G.S. Modeling of the Response of Hydrogen Bond Properties on an External Electric Field: Geometry, NMR Chemical Shift, Spin-Spin Scalar Coupling. Molecules 2021, 26, 4967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derez, T.; Pennock, G.; Drury, M.; Sintubin, M. Deciphering the relationship between different types of low-temperature intracrystalline deformation microstructures in naturally deformed quartz. Programme Abstr. 2013, 39. [Google Scholar]

- Natalia, K.; Paolo, T.; Issei, O.; Julien, H.; Bong-Kyu, B.; Houhun, L.; Sylvie, A.; Alain, R.; Carlos, L.V.; Tzen-Yuh, C. From east to west across the Palearctic: Phylogeography of the invasive lime leaf miner Phyllonorycter issikii (Lepidoptera: Gracillariidae) and discovery of a putative new cryptic species in East Asia. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e171104. [Google Scholar]

- Looney, C.E.; Stewart, J.A.E.; Wood, K.E.A. Mixed-provenance plantings and climatic transfer-distance affect the early growth of knobcone-monterey hybrid pine, a fire-resilient alternative for reforestation. New For. 2024, 55, 543–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulinazzi, T.E.; Fitzsimmons, E.J.; Schrock, S.D.; Roth, R. Economic Impact of Closing Low-Volume Rural Bridges. Econ. Impacts 2013, 2433, 116–120. [Google Scholar]

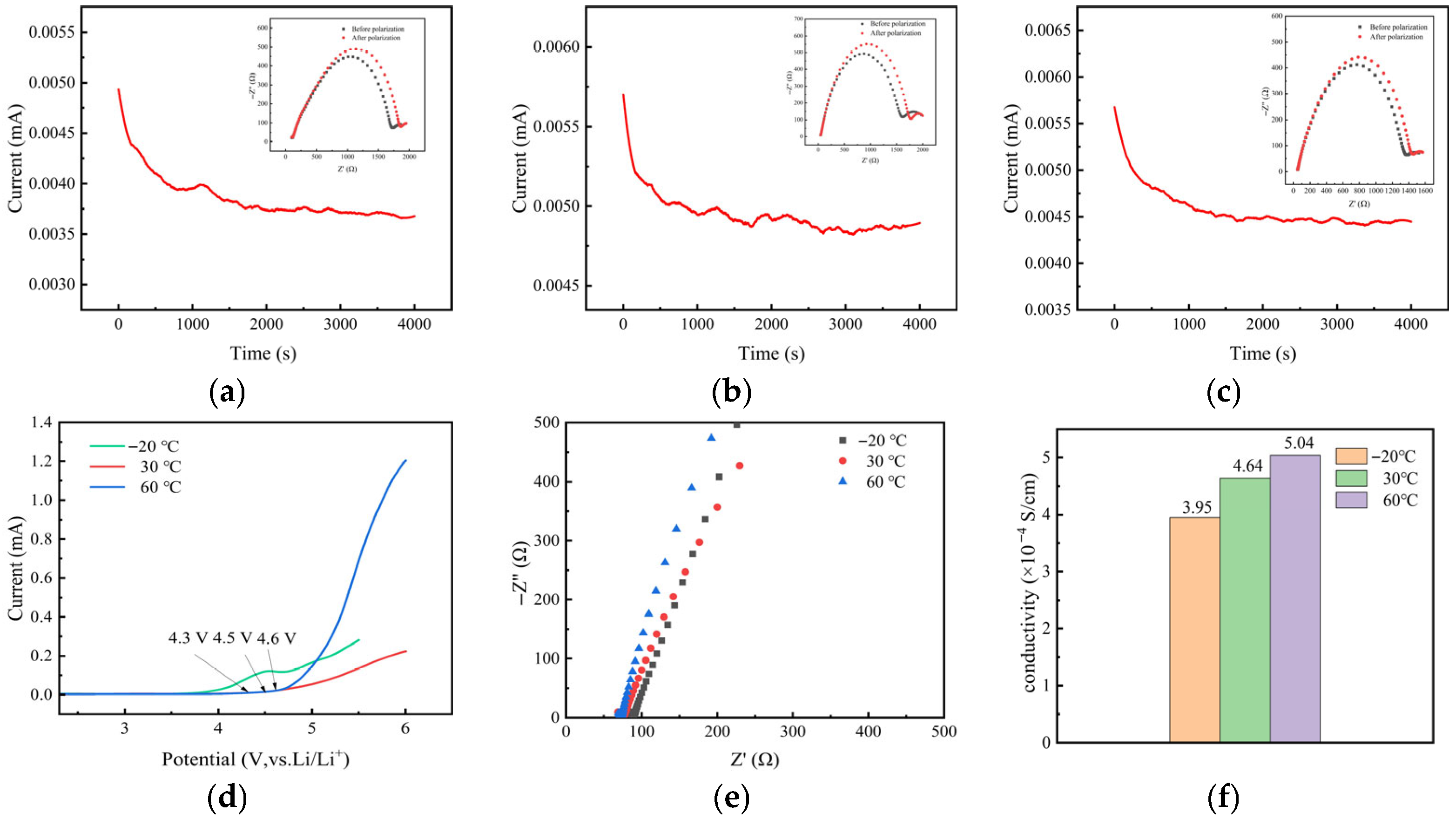

| Temperature (°C) | Impedance/Ω | Ionic Conductivity (×10−4 S·cm−1) |

|---|---|---|

| −20 | 88 | 3.95 |

| 30 | 75 | 4.64 |

| 60 | 69 | 5.04 |

| GPEs | Ionic Conductivity (×10−4 S·cm−1) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| NASICON-type LATP | 2.46 (−20 °C) | [26] |

| PEO-SN | 1.74 (−20 °C) | [27] |

| Li7La3Zr2O12–Li3BO3 | 4.73 (−20 °C) | [28] |

| PEOL-SSLB | 3.52(−20 °C) | [29] |

| YSZ-ZNO | 2.59 (−20 °C) | [30] |

| Li2O-LiF-P2O5 | 5.21 (−20 °C) | [31] |

| PEO-LiFSI | 1.62 (−20 °C) | [32] |

| Li4GeO4–Li3PO4 | 2.67 (−20 °C) | [33] |

| GPEs | 3.95 (−20 °C) | This work |

| Temperature (°C) | I0 (A) | Is (A) | R0 (Ω) | Rs (Ω) | tLi+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −20 | 4.9 × 10−7 | 3.6 × 10−7 | 1639 | 1721 | 0.41 |

| 30 | 5.6 × 10−7 | 4.8 × 10−7 | 1572 | 1630 | 0.53 |

| 60 | 5.8 × 10−7 | 4.4 × 10−7 | 1340 | 1472 | 0.59 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tan, R.; Liang, X.; Hun, Q.; Lan, C.; Lan, L.; Guo, Y. Preparation of Gel Electrolyte for Lithium Metal Solid-State Batteries and Its Failure Behavior at Different Temperatures. Gels 2026, 12, 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12020121

Tan R, Liang X, Hun Q, Lan C, Lan L, Guo Y. Preparation of Gel Electrolyte for Lithium Metal Solid-State Batteries and Its Failure Behavior at Different Temperatures. Gels. 2026; 12(2):121. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12020121

Chicago/Turabian StyleTan, Renji, Xinghua Liang, Qiankun Hun, Chunbo Lan, Lingxiao Lan, and Yifeng Guo. 2026. "Preparation of Gel Electrolyte for Lithium Metal Solid-State Batteries and Its Failure Behavior at Different Temperatures" Gels 12, no. 2: 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12020121

APA StyleTan, R., Liang, X., Hun, Q., Lan, C., Lan, L., & Guo, Y. (2026). Preparation of Gel Electrolyte for Lithium Metal Solid-State Batteries and Its Failure Behavior at Different Temperatures. Gels, 12(2), 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12020121