The Effect of Fructooligosaccharide and Inulin Addition on the Functional, Mechanical, and Structural Properties of Cooked Japonica Rice

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Effect of Adding FOS or Inulin on the Cooking Properties of Japonica Rice

2.2. Effect of Adding FOS or Inulin on the Textural Profiles of Cooked Japonica Rice

2.3. Effect of Adding FOS or Inulin on the Sensory Evaluation Parameters of Cooked Japonica Rice

2.4. Effect of Adding FOS or Inulin on the Pasting Parameters of Japonica Rice Flours

2.5. Effect of Adding FOS or Inulin on the Thermal Parameters of Japonica Rice Flours

2.6. Effect of Adding FOS or Inulin on the Thermo-Mechanical Parameters of Japonica Rice Dough

2.7. Effect of Adding FOS or Inulin on the Starch Crystallinity and Protein Conformation of Cooked Japonica Rice

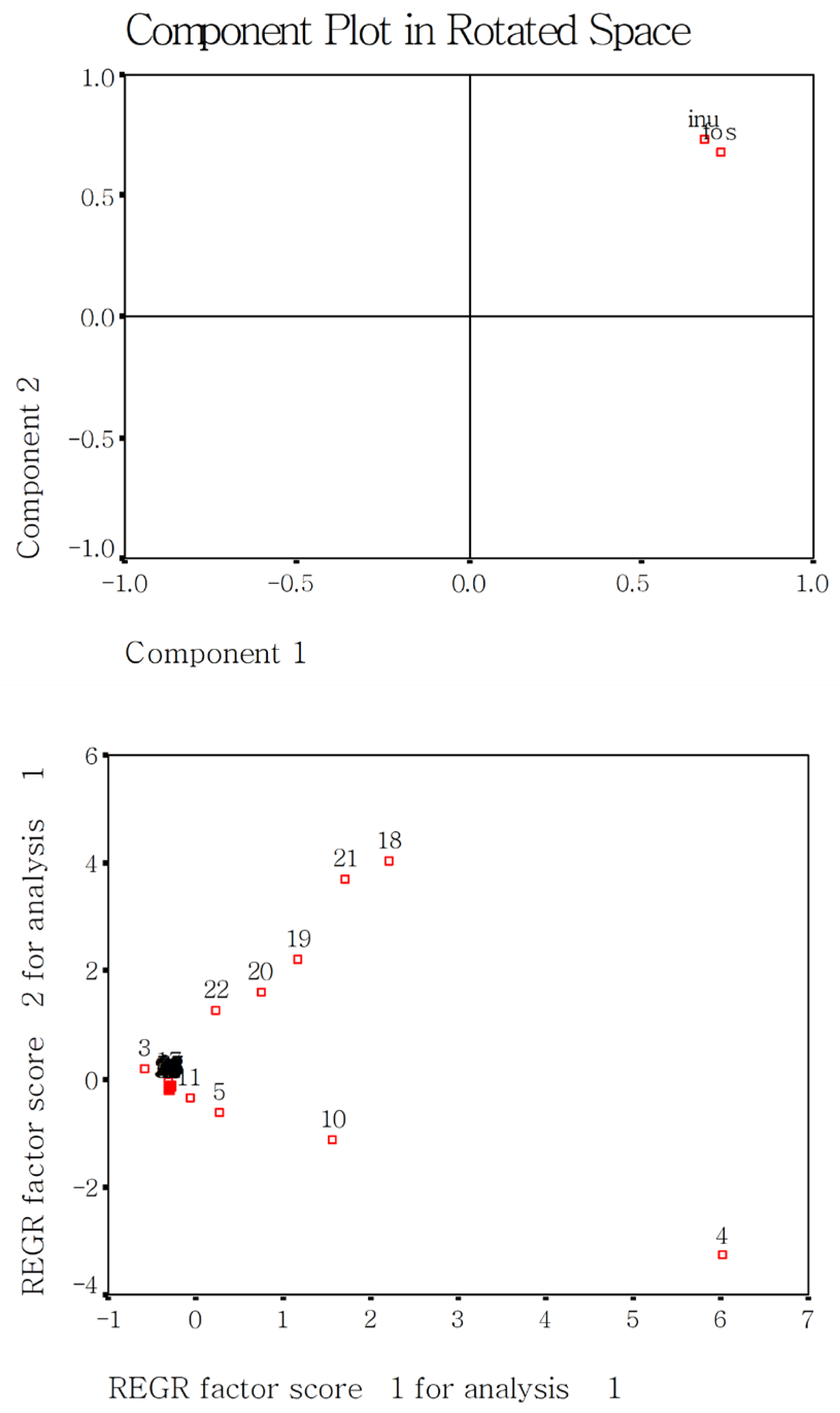

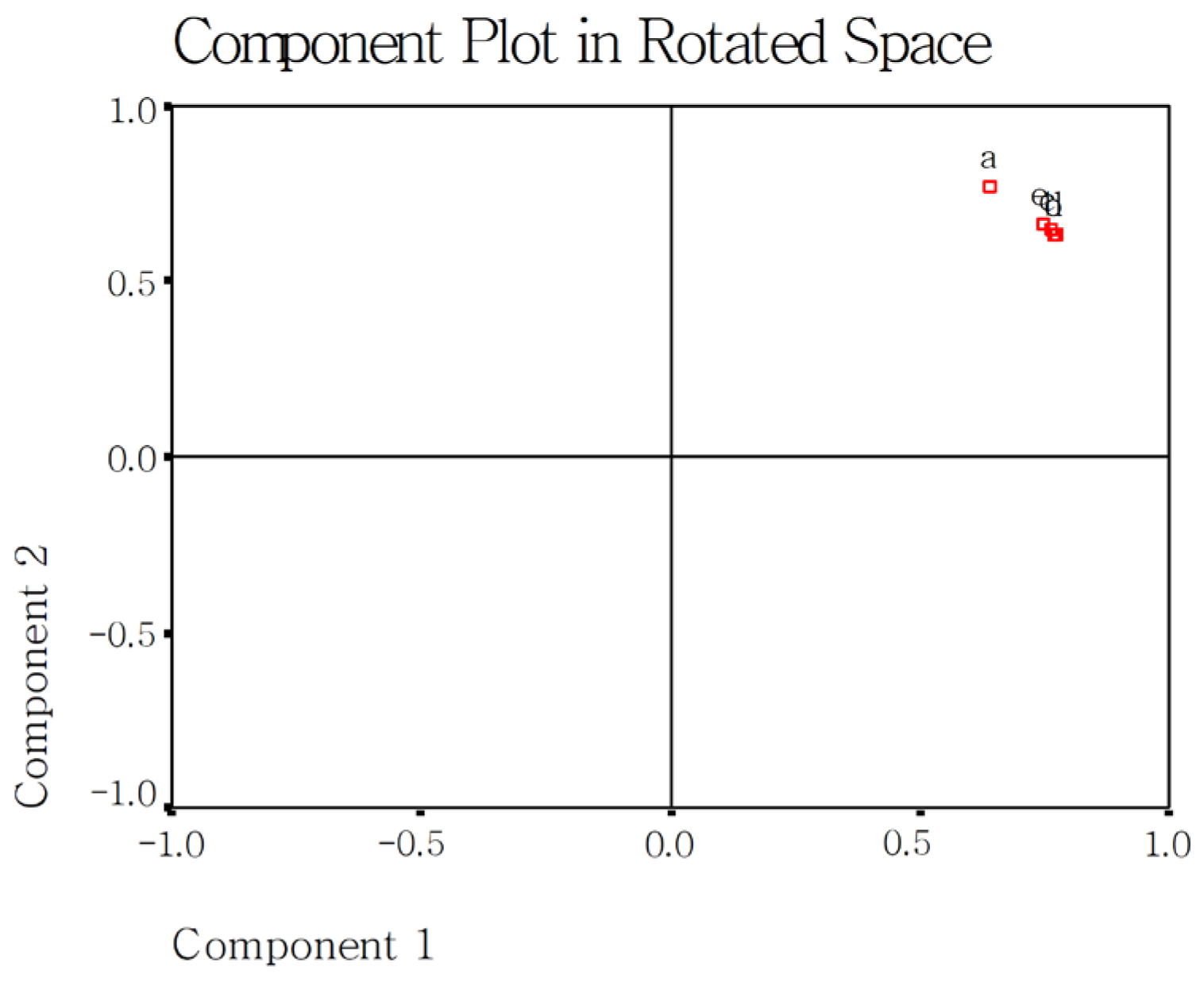

2.8. Effect of Rice Variety, DF Species, and Addition Amount on Cooked Rice Using Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

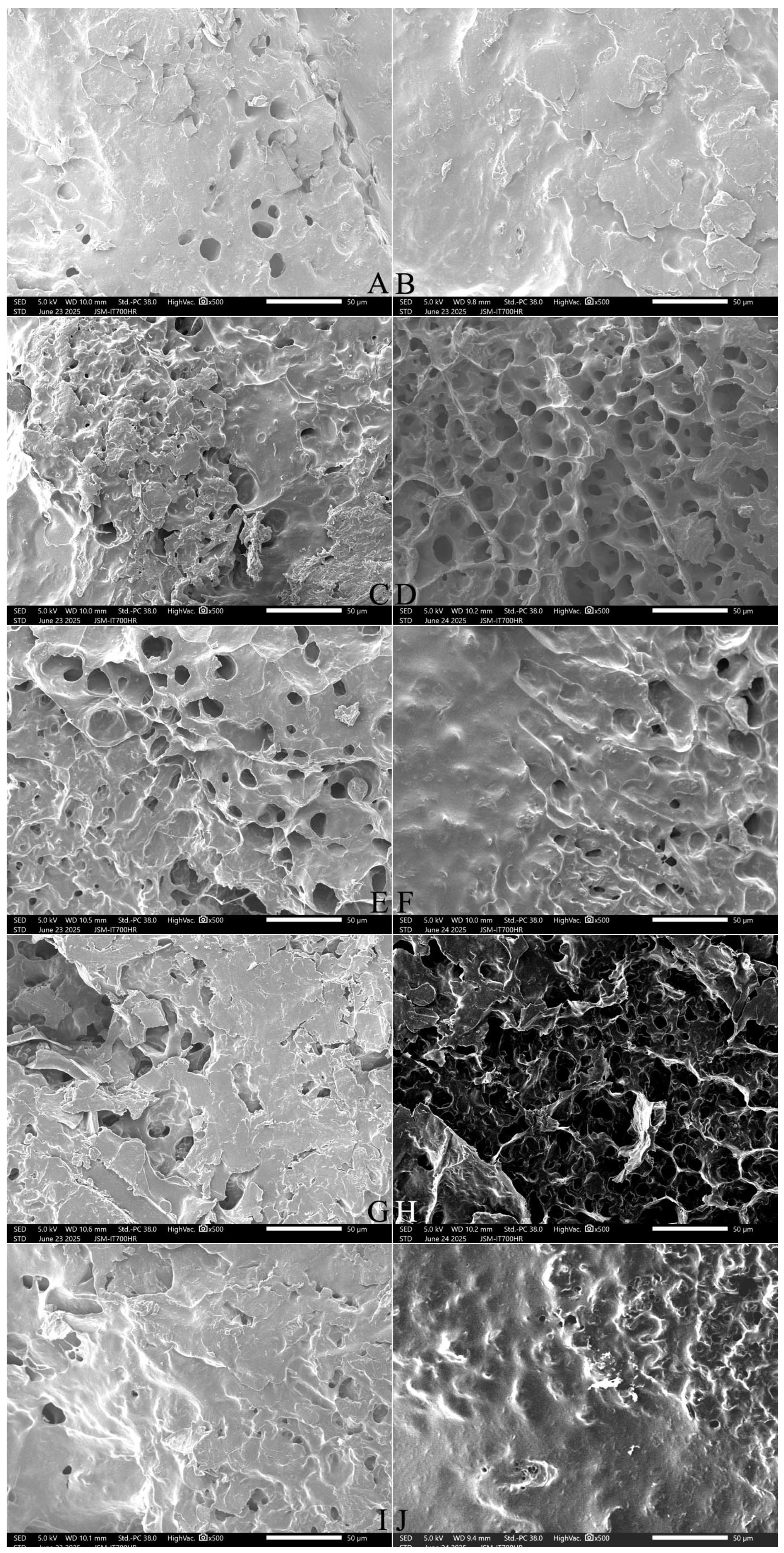

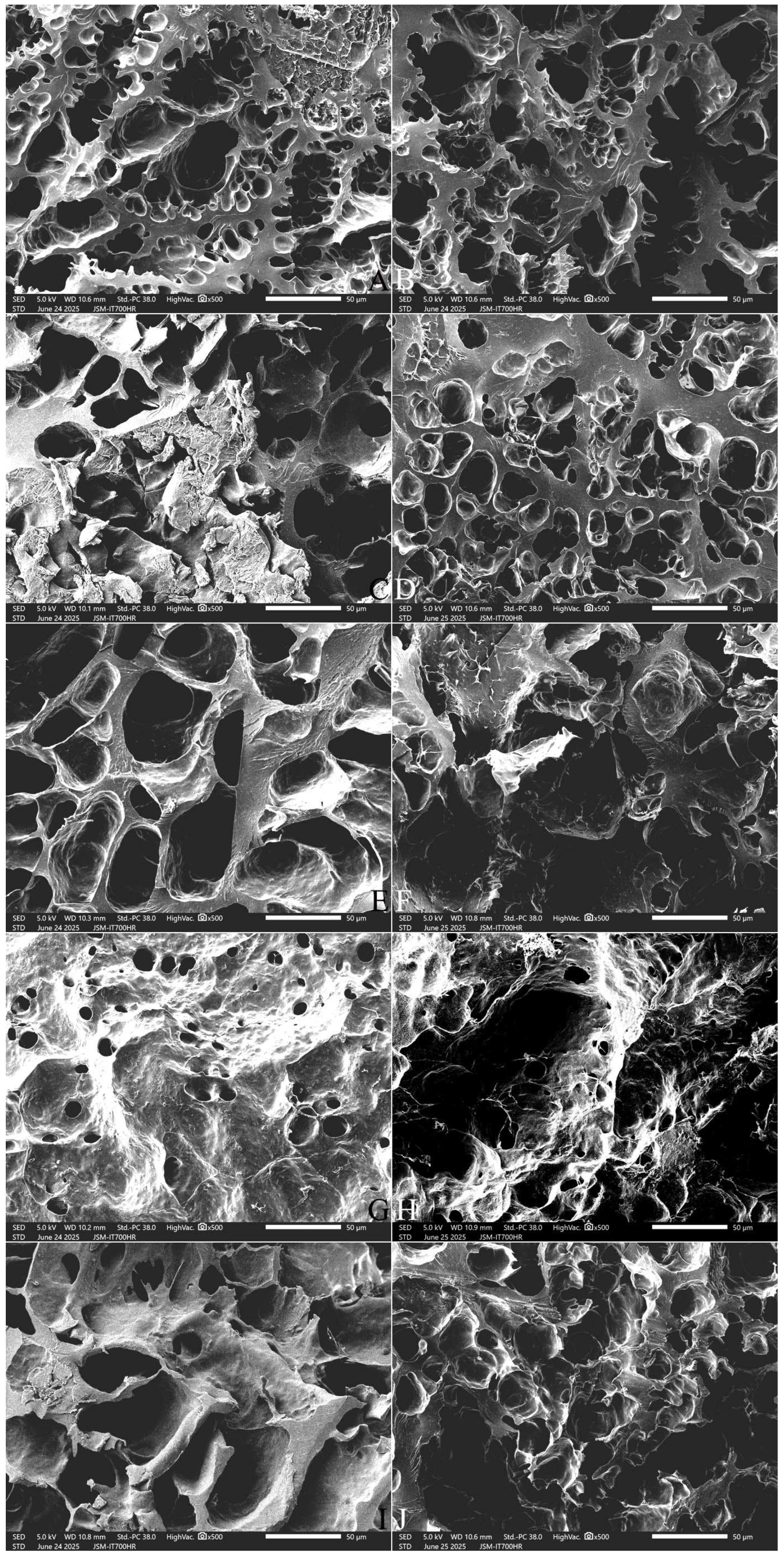

2.9. Effect of Adding FOS or Inulin on the Microstructure of Cooked Japonica Rice

2.9.1. The Surface Microstructure

2.9.2. The Cross-Section Microstructure

2.9.3. The Longitudinal Section Microstructure

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Rice Samples

4.2. Cooking Time, Gruel Solid Loss, and Water Uptake Ratio

4.3. Textural Parameters of Cooked Rice

4.4. Pasting Parameters

4.5. Thermal Parameters

4.6. Thermo-Mechanical Parameters

4.7. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

4.8. Sensory Assessment of Cooked Rice

4.9. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

4.10. Data Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- GB1903.40–2022; National Food Safety Standard, Food Nutritional Fortifiers–Lactulose Fructooligosaccharides (FOS). National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China (NHC): Beijing, China, 2022.

- GB/T41377–2022; The Quality Requirement of Inulin Powder. Standards Administration of China (SAC): Beijing, China, 2022.

- Teferra, T.F. Possible actions of inulin as prebiotic polysaccharide: A review. Food Front. 2021, 2, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juszczak, L.; Witczak, T.; Ziobro, R.; Korus, J.; Cieslik, E.; Witczak, M. Effect of inulin on rheological and thermal properties of gluten-free dough. Carbohydr. Polym. 2012, 90, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, K.K.; Kharb, S.; Thompkinson, D.K. Inulin dietary fiber with functional and health attributes—A review. Food Rev. Int. 2009, 26, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoaib, M.; Shehzad, A.; Omar, M.; Rakha, A.; Raza, H.; Sharif, H.R.; Shakeel, A.; Ansari, A.; Niazi, S. Inulin: Properties, health benefits and food applications. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 147, 444–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canazza, E.; Grauso, M.; Mihaylova, D.; Lante, A. Techno-functional properties and applications of inulin in food systems. Gels 2025, 11, 829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshinpajouh, R.; Heydarian, S.; Amini, M.; Saadatmand, E.; Yahyavi, M. Studies on physical, chemical and rheological characteristics of pasta dough influenced by inulin. Afr. J. Food Sci. 2014, 8, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojnanska, T.; Tokar, M.; Vollmannova, A. Rheological parameters of dough with inulin addition and its effect on bread quality. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2015, 602, 012015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.; Liang, X.; Xu, B.; Kou, X.R.; Li, P.Y.; Han, S.H.; Liu, J.X.; Zhou, L. Effect of inulin with different degree of polymerization on plain wheat dough rheology and the quality of steamed bread. J. Cereal Sci. 2017, 75, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.L.; Kou, X.R.; Zhang, T.; Nie, Y.; Xu, B.C.; Li, P.Y.; Li, X.; Han, S.H.; Liu, J.X. Effect of inulin on rheological properties of soft and strong wheat dough. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 53, 1648–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Lal, M.K.; Bagchi, T.B.; Sah, R.P.; Sharma, S.G.; Baig, M.J.; Nayak, A.K. Glycemic Index of Rice: Role in Diabetics; NRRI Research Bulletin No. 44; ICAR–National Rice Research Institute: Cuttack, India, 2024; p. 753006. [Google Scholar]

- Lal, M.K.; Singh, B.; Sharma, S.; Singh, M.P.; Kumar, A. Glycemic index of starchy crops and factors affecting its digestibility: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 111, 741–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamil, K.M.; Rohana, A.J.; Mohamed, W.M.; Ishak, W.R. Effect of incorporating dietary fiber sources in bakery products on glycemic index and starch digestibility response: A review. Nutrire 2023, 48, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Industry Research Network. China Inulin Development Status and Prospect Analysis Report (2025–2031); Report No. 3272029. Industry Research Network: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2025.

- Ma, T.; Zhu, M.P. Deep Processing of Rice; China Cheminal Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2020; pp. 1–100. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, W.D. SPSS for Windows Statistical Analysis, Version 2; China Electronic Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2002; pp. 311–334. [Google Scholar]

- Garbetta, A.; D’Antuono, I.; Melilli, M.G.; Sillitti, C.; Linsalata, V.; Scandurra, S.; Cardinali, A. Inulin enriched durum wheat spaghetti: Effect of polymerization degree on technological and nutritional characteristics. J. Funct. Foods 2020, 71, 104004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, J.H.; Franco, C.M. Changes in rheology, quality, and staling of white breads enriched with medium-polymerized inulin. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2021, 28, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cauvain, S.P. Bread: Breadmaking Processes. In Encyclopedia of Food and Health, 3rd ed.; Elsevier Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Handa, C.; Goomer, S.; Siddhu, A. Physicochemical properties and sensory evaluation of fructoligosaccharide enriched cookies. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2012, 49, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Leng, Y.; Xiao, S.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, W.; Ding, B.; Wu, Y.; Wang, X.; Fu, Y. Effect of inulin with different degrees of polymerization on dough rheology, gelatinization, texture and protein composition properties of extruded flour products. LWT 2022, 159, 113225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, K.; Kamilah, H.; Shang, P.; Sulaiman, S.; Ariffin, F.; Alias, A. A review: Interaction of starch/non-starch hydrocolloid blending and the recent food applications. Food Biosci. 2017, 19, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.J.; Li, C.L.; Copeland, L.; Niu, Q.; Wang, S. Starch retrogradation: A comprehensive review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2015, 14, 568–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, B.; Chen, R.J.; Wei, Z.; Wu, J.Z.; Li, X.J. Moisture sorption isotherms of fructooligosaccharide and inulin powders and their gelling competence in delaying the retrogradation of rice starch. Gels 2025, 11, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.Y.; Liu, C.; Luo, X.H.; Wu, J.Z.; Li, X.J. Effect of polydextrose on the cooking and gelatinization properties and microstructure of Chinese early indica rice. Gels 2025, 11, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biliaderis, C.G.; Prokopowich, D.J. Effect of polyhydroxy compounds on structure formation in waxy maize starch gels-a calorimetric study. Carbohydr. Polym. 1994, 23, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sifuentes-Nieves, I.; Mendez-Montealvo, G.; Flores-Silva, P.C.; Nieto-Pérez, M.; Neira-Velazquez, G.; Rodriguez-Fernandez, O.; Hernández-Hernández, E.; Velazquez, G. Dielectric barrier discharge and radiofrequency plasma effect on structural properties of starches with different amylose content. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2021, 68, 102630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Chang, B.; Huang, G.; Wang, D.; Gao, Y.; Fan, Z.; Sun, H.; Sui, X. Differential enzymatic hydrolysis: A study on its impact on soy protein structure, function, and soy milk powder properties. Foods 2025, 14, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, G.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Sui, X. Secondary structural analysis using Fourier transform infrared and circular dichroism spectroscopy. In Plant-Based Proteins: Production, Physicochemical, Functional, and Sensory Properties; Li, Y., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 265–277. [Google Scholar]

- Aravind, N.; Sissons, M.J.; Fellows, C.M.; Blazek, J.; Gilbert, E.P. Effect of inulin soluble dietary fibre addition on technological, sensory, and structural properties of durum wheat spaghetti. Food Chem. 2012, 132, 993–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Dai, B.; Luo, X.H.; Song, H.D.; Li, X.J. Polydextrose reduces the hardness of cooked Chinese sea rice through intermolecular interactions. Gels 2025, 11, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Li, X.Y.; Song, H.D.; Li, X.J. Moisture sorption isotherms of polydextrose and its gelling efficiency in inhibiting the retrogradation of rice starch. Gels 2024, 10, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Q.S.; Duan, Y.M.; Xiao, Z.G.; Wang, K.X.; Li, H.; Wang, N.; Wang, Y.F.; Gao, Y.Z. Effects of extrusion stabilization on protein structure and functional properties of rice bran components. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2020, 36, 283–290. [Google Scholar]

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis, 13th ed.; Association of Official Analytical Chemists: Washington, DC, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- GB/T15683–2008; Rice–Determination of Amylose Content. Standards Administration of China (SAC): Beijing, China, 2008.

- ISO 14891–2002; Milk and Milk Products–Determination of Nitrogen Content–Routine Method Using Combustion According to the Dumas Principle. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002.

- GB/T5510–2024; Inspection of Grain and Oils–Determination of Fat Acidity Value of Cereal and Cereal Products. Standards Administration of China (SAC): Beijing, China, 2024.

- Zhou, Z.K.; Robards, K.; Helliwell, S.; Blanchard, C. Effect of storage temperature on cooking behaviour of rice. Food Chem. 2007, 105, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T15682–2008; Inspection of Grain and Oils–Method for Sensory Evaluation of Paddy or Rice Cooking and Eating Quality. Standards Administration of China (SAC): Beijing, China, 2008.

- GB/T24852–2010; Determination of Pasting Properties of Rice–Rapid Visco Analyzer Method. Standards Administration of China (SAC): Beijing, China, 2010.

- SPSS Inc. SPSS for Windows; Release 17.0.1; SPSS Inc.: Chicago, IL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

| Factor | Levels | Cooking Time (min) | Water Absorption Ratio | Gruel Solid Loss (mg/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice | SQ | 19.939 ± 0.054 a | 3.003 ± 0.047 b | 73.256 ± 2.007 d |

| variety | NJ5 | 17.989 ± 0.054 g | 2.871 ± 0.047 c | 87.224 ± 2.007 c |

| DF | FOS | 18.839 ± 0.054 de | 3.163 ± 0.047 a | 67.838 ± 2.007 e |

| species | INU | 18.988 ± 0.054 c | 2.711 ± 0.047 d | 92.642 ± 2.007 b |

| Addition | 0 | 19.357 ± 0.085 b | 2.928 ± 0.075 bc | 47.025 ± 3.173 f |

| (%) | 3 | 19.230 ± 0.085 b | 2.797 ± 0.075 cd | 66.234 ± 3.173 e |

| 5 | 18.928 ± 0.085 cd | 3.042 ± 0.075 ab | 77.956 ± 3.173 d | |

| 7 | 18.733 ± 0.085 ef | 3.019 ± 0.075 b | 91.833 ± 3.173 bc | |

| 10 | 18.571 ± 0.085 f | 2.897 ± 0.075 bc | 118.153 ± 3.173 a |

| Factor | Levels | Hardness (g) | Adhesive force(g) | Adhesiveness (mJ) | Resilience (0.1) | Cohesiveness (0.1) | Springiness (mm) | Gumminess (g) | Chewiness (mJ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice | SQ | 2354 ± 76 b | 106 ± 5 b | 2.60 ± 0.19 b | 1.33 ± 0.04 abc | 3.03 ± 0.04 a | 9.21 ± 0.24 a | 707 ± 23 b | 67.8 ± 3.3 b |

| variety | NJ5 | 1477 ± 76 e | 84 ± 5 cd | 1.78 ± 0.19 c | 1.27 ± 0.04 bcd | 2.91 ± 0.04 bc | 7.47 ± 0.24 d | 431 ± 23 f | 32.8 ± 3.3 e |

| DF | FOS | 2155 ± 76 c | 119 ± 5 a | 2.83 ± 0.19 ab | 1.25 ± 0.04 cd | 2.96 ± 0.04 abc | 9.10 ± 0.24 a | 640 ± 23 c | 59.8 ± 3.3 c |

| species | INU | 1676 ± 76 d | 72 ± 5 e | 1.55 ± 0.19 c | 1.34 ± 0.04 ab | 2.98 ± 0.04 ab | 7.58 ± 0.24 cd | 498 ± 23 de | 40.8 ± 3.3 d |

| Addition | 0 | 3011 ± 121 a | 128 ± 8 a | 3.11 ± 0.30 a | 1.17 ± 0.06 d | 2.97 ± 0.06 abc | 9.60 ± 0.38 a | 892 ± 36 a | 89.7 ± 5.2 a |

| (%) | 3 | 1564 ± 121 de | 77 ± 8 de | 1.41 ± 0.30 c | 1.42 ± 0.06 a | 3.00 ± 0.06 ab | 7.88 ± 0.38 bcd | 474 ± 36 def | 39.1 ± 5.2 de |

| 5 | 1748 ± 121 d | 103 ± 8 b | 2.57 ± 0.30 ab | 1.27 ± 0.06 bcd | 3.02 ± 0.06 a | 8.20 ± 0.38 bc | 529 ± 36 d | 43.8 ± 5.2 d | |

| 7 | 1567 ± 121 de | 75 ± 8 de | 1.46 ± 0.30 c | 1.33 ± 0.06 abc | 2.87 ± 0.06 c | 7.56 ± 0.38 cd | 446 ± 36 ef | 35.9 ± 5.2 de | |

| 10 | 1687 ± 121 d | 94 ± 8 bc | 2.41 ± 0.30 b | 1.31 ± 0.06 abc | 3.00 ± 0.06 ab | 8.46 ± 0.38 b | 504 ± 36 de | 42.9 ± 5.2 d |

| Factor | Levels | Smell (%) | Appearance Structure (%) | Palatability (%) | Taste (%) | Cool Rice Texture (%) | Total Score (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice | SQ | 17.54 ± 0.21 a | 17.36 ± 0.15 ab | 23.96 ± 0.27 ab | 22.06 ± 0.18 b | 4.34 ± 0.06 ab | 85.26 ± 0.55 ab |

| variety | NJ5 | 16.86 ± 0.21 c | 17.26 ± 0.15 bc | 23.32 ± 0.27 c | 22.02 ± 0.18 b | 4.16 ± 0.06 c | 83.62 ± 0.55 cd |

| DF | FOS | 16.82 ± 0.21 c | 16.98 ± 0.15 c | 23.06 ± 0.27 c | 21.98 ± 0.18 b | 4.26 ± 0.06 bc | 83.10 ± 0.55 d |

| species | INU | 17.58 ± 0.21 a | 17.64 ± 0.15 a | 24.22 ± 0.27 a | 22.10 ± 0.18 b | 4.24 ± 0.06 bc | 85.78 ± 0.55 a |

| Addition | 0 | 16.80 ± 0.34 c | 17.50 ± 0.24 ab | 23.40 ± 0.43 bc | 21.50 ± 0.29 c | 4.10 ± 0.10 c | 83.30 ± 0.86 cd |

| (%) | 3 | 17.25 ± 0.34 abc | 17.35 ± 0.24 abc | 24.05 ± 0.43 ab | 21.50 ± 0.29 c | 4.15 ± 0.10 c | 84.30 ± 0.86 bcd |

| 5 | 17.60 ± 0.34 a | 17.30 ± 0.24 abc | 24.20 ± 0.43 ab | 22.00 ± 0.29 bc | 4.50 ± 0.10 a | 85.60 ± 0.86 ab | |

| 7 | 16.85 ± 0.34 bc | 17.45 ± 0.24 ab | 23.55 ± 0.43 abc | 22.45 ± 0.29 ab | 4.25 ± 0.10 bc | 84.55 ± 0.86 abc | |

| 10 | 17.50 ± 0.34 ab | 16.95 ± 0.24 c | 23.00 ± 0.43 c | 22.75 ± 0.29 a | 4.25 ± 0.10 bc | 84.45 ± 0.86 abcd |

| Factor | Levels | Peak Viscosity (cp) | Trough Viscosity (cp) | Breakdown Viscosity (cp) | Final Viscosity (cp) | Setback Viscosity (cp) | Peak Time (min) | Pasting Temp (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice | SQ | 4586 ± 13 a | 2298 ± 28 bc | 2289 ± 35 a | 3581 ± 25 b | 1284 ± 5 a | 5.81 ± 0.02 f | 74.46 ± 0.08 a |

| variety | NJ5 | 3339 ± 13 g | 2262 ± 28 bc | 1077 ± 35 h | 3356 ± 25 e | 1095 ± 5 f | 6.33 ± 0.02 a | 71.69 ± 0.08 g |

| DF | FOS | 4009 ± 13 d | 2308 ± 28 b | 1702 ± 35 d | 3501 ± 25 c | 1194 ± 5 c | 6.08 ± 0.02 cd | 72.99 ± 0.08 e |

| species | INU | 3916 ± 13 e | 2252 ± 28 bc | 1664 ± 35 de | 3436 ± 25 d | 1184 ± 5 c | 6.07 ± 0.02 cd | 73.17 ± 0.08 d |

| Addition | 0 | 4549 ± 20 b | 2399 ± 44 a | 2149 ± 55 b | 3683 ± 40 a | 1284 ± 7 a | 5.93 ± 0.03 e | 72.32 ± 0.13 f |

| (%) | 3 | 4162 ± 20 c | 2296 ± 44 bc | 1866 ± 55 c | 3549 ± 40 bc | 1254 ± 7 b | 6.02 ± 0.03 d | 72.53 ± 0.13 f |

| 5 | 3994 ± 20 d | 2401 ± 44 a | 1593 ± 55 ef | 3571 ± 40 b | 1169 ± 7 d | 6.14 ± 0.03 b | 73.10 ± 0.13 d | |

| 7 | 3737 ± 20 f | 2228 ± 44 c | 1509 ± 55 f | 3364 ± 40 e | 1136 ± 7 e | 6.11 ± 0.03 bc | 73.45 ± 0.13 c | |

| 10 | 3371 ± 20 g | 2074 ± 44 d | 1296 ± 55 g | 3177 ± 40 f | 1102 ± 7 f | 6.16 ± 0.03 b | 73.99 ± 0.13 b |

| Factor | Levels | ΔH (J/g) | To (°C) | Tp (°C) | Tc (°C) | Peak Width (°C) | Peak Height (0.01 mw/mg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice | SQ | 6.435 ± 0.072 cd | 63.837 ± 0.358 a | 70.750 ± 0.317 a | 77.493 ± 0.215 a | 6.687 ± 0.136 d | 12.990 ± 0.314 a |

| variety | NJ5 | 6.472 ± 0.072 c | 59.415 ± 0.358 e | 67.383 ± 0.317 e | 74.720 ± 0.215 d | 7.333 ± 0.136 a | 11.601 ± 0.314 d |

| DF | FOS | 6.272 ± 0.072 e | 62.373 ± 0.358 b | 69.550 ± 0.317 b | 76.293 ± 0.215 b | 6.843 ± 0.136 cd | 12.462 ± 0.314 abc |

| species | INU | 6.636 ± 0.072 b | 60.878 ± 0.358 cd | 68.583 ± 0.317 cd | 75.920 ± 0.215 bc | 7.177 ± 0.136 ab | 12.127 ± 0.496 bcd |

| Addition | 0 | 7.158 ± 0.115 a | 60.400 ± 0.567 d | 68.017 ± 0.501 de | 75.533 ± 0.340 c | 7.233 ± 0.214 ab | 12.932 ± 0.496 ab |

| (%) | 3 | 6.661 ± 0.115 b | 62.333 ± 0.567 b | 69.533 ± 0.501 b | 76.458 ± 0.340 b | 7.108 ± 0.214 abc | 13.174 ± 0.496 a |

| 5 | 6.265 ± 0.115 de | 62.058 ± 0.567 b | 69.508 ± 0.501 b | 76.350 ± 0.340 b | 6.775 ± 0.214 cd | 12.041 ± 0.496 bcd | |

| 7 | 6.263 ± 0.115 de | 61.567 ± 0.567 bc | 69.008 ± 0.501 bcd | 76.050 ± 0.340 bc | 7.033 ± 0.214 abcd | 11.933 ± 0.496 cd | |

| 10 | 5.920 ± 0.115 f | 61.777 ± 0.567 bc | 69.267 ± 0.501 bc | 76.142 ± 0.340 bc | 6.901 ± 0.214 bcd | 11.394 ± 0.496 d |

| Factor | Levels | ΔH (J/g) | To (°C) | Tp (°C) | Tc (°C) | Peak Width (°C) | Peak Height (0.01 mw/mg) | Aging (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice | SQ | 1.780 ± 0.072 d | 47.793 ± 1.185 a | 58.477 ± 0.210 a | 63.833 ± 0.635 a | 9.423 ± 0.129 ab | 2.728 ± 0.102 d | 21.414 ± 0.915 c |

| variety | NJ5 | 2.275 ± 0.072 b | 48.917 ± 1.185 a | 55.490 ± 0.210 f | 60.847 ± 0.635 c | 9.291 ± 0.129 ab | 3.621 ± 0.102 b | 31.003 ± 0.915 a |

| DF | FOS | 1.982 ± 0.072 c | 49.227 ± 1.185 a | 57.153 ± 0.210 cd | 62.991 ± 0.635 ab | 9.190 ± 0.129 b | 3.161 ± 0.102 c | 26.131 ± 0.915 b |

| species | INU | 2.075 ± 0.072 c | 47.483 ± 1.185 a | 56.813 ± 0.210 d | 61.690 ± 0.635 c | 9.529 ± 0.129 a | 3.188 ± 0.102 c | 26.286 ± 0.915 b |

| Addition | 0 | 1.913 ± 0.113 cd | 46.733 ± 1.873 a | 57.467 ± 0.332 bc | 61.350 ± 1.003 c | 9.550 ± 0.204 a | 2.945 ± 0.162 cd | 23.312 ± 1.447 c |

| (%) | 3 | 2.678 ± 0.113 a | 49.892 ± 1.873 a | 56.192 ± 0.332 e | 64.033 ± 1.003 a | 9.542 ± 0.204 a | 4.125 ± 0.162 a | 32.783 ± 1.447 a |

| 5 | 2.121 ± 0.113 bc | 49.567 ± 1.873 a | 56.850 ± 0.332 cde | 63.808 ± 1.003 a | 9.608 ± 0.204 a | 3.215 ± 0.162 c | 26.932 ± 1.447 b | |

| 7 | 2.032 ± 0.113 c | 46.892 ± 1.873 a | 56.708 ± 0.332 de | 61.617 ± 1.003 bc | 9.442 ± 0.204 ab | 3.194 ± 0.162 c | 26.940 ± 1.447 b | |

| 10 | 1.396 ± 0.113 e | 48.692 ± 1.873 a | 57.701 ± 0.332 b | 60.892 ± 1.003 c | 8.642 ± 0.204 c | 2.393 ± 0.162 e | 21.075 ± 1.447 c |

| Factor | Levels | DDT(min) | DST(min) | C1–Cs (0.1 Nm) | C3(Nm) | C3/C4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice | SQ | 1.349 ± 0.054 de | 1.700 ± 0.212 b | 5.45 ± 0.35 c | 1.868 ± 0.006 a | 1.220 ± 0.015 e |

| variety | NJ5 | 1.365 ± 0.054 cd | 1.783 ± 0.212 b | 6.54 ± 0.35 b | 1.756 ± 0.006 d | 1.278 ± 0.015 ab |

| DF | FOS | 1.254 ± 0.054 ef | 1.760 ± 0.212 b | 6.49 ± 0.35 b | 1.825 ± 0.006 b | 1.264 ± 0.015 bc |

| species | INU | 1.460 ± 0.054 bc | 1.723 ± 0.212 b | 5.50 ± 0.35 c | 1.799 ± 0.006 c | 1.234 ± 0.015 cde |

| Addition | 0 | 1.112 ± 0.086 g | 0.867 ± 0.335 c | 10.20 ± 0.57 a | 1.795 ± 0.010 c | 1.307 ± 0.023 a |

| (%) | 3 | 1.193 ± 0.086 fg | 1.567 ± 0.335 b | 6.07 ± 0.57 bc | 1.832 ± 0.010 b | 1.282 ± 0.023 ab |

| 5 | 1.348 ± 0.086 cdef | 1.308 ± 0.335 bc | 6.22 ± 0.57 bc | 1.827 ± 0.010 b | 1.267 ± 0.023 abcd | |

| 7 | 1.527 ± 0.086 ab | 2.542 ± 0.335 a | 4.07 ± 0.57 d | 1.817 ± 0.010 b | 1.221 ± 0.023 de | |

| 10 | 1.605 ± 0.086 a | 2.425 ± 0.335 a | 3.40 ± 0.57 d | 1.789 ± 0.010 c | 1.170 ± 0.023 f | |

| Factor | Levels | C3–C4(0.1 Nm) | C5–C4(0.1 Nm) | α(−0.01 Nm) | β(0.01 Nm) | γ(−0.01 Nm) |

| Rice | SQ | 3.26 ± 0.20 d | 7.72 ± 0.19 c | 8.03 ± 0.15 de | 30.99 ± 0.52 a | 5.49 ± 0.48 abc |

| variety | NJ5 | 3.78 ± 0.20 a | 8.11 ± 0.19 ab | 9.59 ± 0.15 a | 28.77 ± 0.52 c | 5.46 ± 0.48 abc |

| DF | FOS | 3.72 ± 0.20 abc | 7.91 ± 0.19 bc | 9.18 ± 0.15 b | 30.66 ± 0.52 a | 6.21 ± 0.48 a |

| species | INU | 3.32 ± 0.20 cd | 7.91 ± 0.19 bc | 8.45 ± 0.15 c | 29.10 ± 0.52 bc | 4.74 ± 0.48 c |

| Addition | 0 | 4.04 ± 0.31 a | 7.12 ± 0.31 d | 9.43 ± 0.23 ab | 26.80 ± 0.82 d | 6.47 ± 0.76 a |

| (%) | 3 | 3.95 ± 0.31 a | 7.73 ± 0.31 bcd | 9.13 ± 0.23 b | 30.02 ± 0.82 abc | 4.30 ± 0.76 c |

| 5 | 3.84 ± 0.31 ab | 8.49 ± 0.31 a | 9.38 ± 0.23 ab | 30.37 ± 0.82 ab | 5.82 ± 0.76 abc | |

| 7 | 3.23 ± 0.31 bcd | 7.89 ± 0.31 abc | 8.30 ± 0.23 cd | 30.93 ± 0.82 a | 6.10 ± 0.76 ab | |

| 10 | 2.55 ± 0.31 e | 8.29 ± 0.31 ab | 7.82 ± 0.23 e | 31.28 ± 0.82 a | 4.68 ± 0.76 bc |

| Factor | Levels | R1022/995 | R1047/1022 | R1068/1022 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice | SQ | 1.033 ± 0.002 c | 0.947 ± 0.002 abc | 0.857 ± 0.004 abc | |

| variety | NJ5 | 1.047 ± 0.002 ab | 0.941 ± 0.002 de | 0.846 ± 0.004 d | |

| DF | FOS | 1.046 ± 0.002 ab | 0.938 ± 0.002 ef | 0.842 ± 0.004 d | |

| species | INU | 1.034 ± 0.002 c | 0.949 ± 0.002 ab | 0.861 ± 0.004 ab | |

| Addition | 0 | 1.051 ± 0.004 a | 0.944 ± 0.003 bcd | 0.851 ± 0.004 bcd | |

| (%) | 3 | 1.029 ± 0.004 c | 0.951 ± 0.003 a | 0.866 ± 0.004 a | |

| 5 | 1.048 ± 0.004 a | 0.935 ± 0.003 f | 0.829 ± 0.004 e | ||

| 7 | 1.041 ± 0.004 b | 0.942 ± 0.003 cde | 0.847 ± 0.004 cd | ||

| 10 | 1.031 ± 0.004 c | 0.947 ± 0.003 abc | 0.864 ± 0.004 a | ||

| Factor | Levels | β-Sheet(%) | Random coil(%) | α-Helix (%) | β-Turn (%) |

| Rice | SQ | 54.546 ± 0.070 cd | 15.331 ± 0.031 b | 15.553 ± 0.035 c | 14.570 ± 0.035 abc |

| variety | NJ5 | 54.697 ± 0.070 b | 15.161 ± 0.031 ef | 15.599 ± 0.035 bc | 14.543 ± 0.035 bc |

| DF | FOS | 54.522 ± 0.070 cd | 15.286 ± 0.031 bc | 15.594 ± 0.035 bc | 14.598 ± 0.035 ab |

| species | INU | 54.722 ± 0.070 b | 15.206 ± 0.031 de | 15.558 ± 0.035 c | 14.514 ± 0.035 cd |

| Addition | 0 | 55.043 ± 0.111 a | 15.122 ± 0.049 f | 15.389 ± 0.055 d | 14.446 ± 0.039 d |

| (%) | 3 | 54.749 ± 0.111 b | 15.183 ± 0.049 def | 15.539 ± 0.055 c | 14.529 ± 0.039 bc |

| 5 | 54.233 ± 0.111 e | 15.422 ± 0.049 a | 15.708 ± 0.055 a | 14.638 ± 0.039 a | |

| 7 | 54.410 ± 0.111 de | 15.271 ± 0.049 bcd | 15.678 ± 0.055 ab | 14.641 ± 0.039 a | |

| 10 | 54.674 ± 0.111 bc | 15.232 ± 0.049 cde | 15.566 ± 0.055 c | 14.528 ± 0.039 bc |

| Rice Variety | Moisture Content (%) | Kernel Length -to-Width Ratio | Taste Value (%) | Fatty Acid Value (mgKOH/100 g) | Amylose (%) | Protein(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SQ | 12.30 ± 0.07 b | 1.72 ± 0.01 a | 79.31 ± 1.24 b | 9.61 ± 0.03 a | 15.74 ± 0.48 b | 9.51 ± 0.19 a |

| NJ5 | 12.01 ± 0.10 a | 1.80 ± 0.06 a | 86.33 ± 0.58 a | 5.48 ± 2.07 b | 17.57 ± 0.25 a | 8.23 ± 0.15 b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dai, B.; Chen, R.; Chang, S.; Wei, Z.; Luo, X.; Wu, J.; Li, X. The Effect of Fructooligosaccharide and Inulin Addition on the Functional, Mechanical, and Structural Properties of Cooked Japonica Rice. Gels 2026, 12, 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010048

Dai B, Chen R, Chang S, Wei Z, Luo X, Wu J, Li X. The Effect of Fructooligosaccharide and Inulin Addition on the Functional, Mechanical, and Structural Properties of Cooked Japonica Rice. Gels. 2026; 12(1):48. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010048

Chicago/Turabian StyleDai, Bing, Ruijun Chen, Shiyu Chang, Zheng Wei, Xiaohong Luo, Jiangzhang Wu, and Xingjun Li. 2026. "The Effect of Fructooligosaccharide and Inulin Addition on the Functional, Mechanical, and Structural Properties of Cooked Japonica Rice" Gels 12, no. 1: 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010048

APA StyleDai, B., Chen, R., Chang, S., Wei, Z., Luo, X., Wu, J., & Li, X. (2026). The Effect of Fructooligosaccharide and Inulin Addition on the Functional, Mechanical, and Structural Properties of Cooked Japonica Rice. Gels, 12(1), 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010048