Alginate-Based Beads Containing Artemisia absinthium L. Extract as Innovative Ingredients for Baked Products

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Preparation and Characterisation of Artemisia absinthium L. Extract

2.2. Microparticles Obtained by Spray Drying

2.3. Microparticles Obtained by Ionotropic Gelation

2.4. Biscuits Characterization

2.4.1. Proximate Composition

2.4.2. Total Phenols Content and Antioxidant Activity

2.4.3. FAME Analysis

2.4.4. Quantification of Bitter Compounds Extracted from Biscuits

2.5. Consumer Acceptance

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Experimental Methods

4.2.1. Ethanolic Extraction of Artemisia absinthium L.

4.2.2. Characterization of AAE

Total Phenolic Content (TPC) and Antioxidant Activity (AA) of the Extract

4.2.3. Preliminary Formulation Studies

Spray Drying

Ionotropic Gelation

4.2.4. Preparation of the Microparticles

Spray Drying

Ionotropic Gelation

4.2.5. Characterization of the MPs

Morphology and Particle Size

Flowability

Residual Moisture and Thermal Behaviour

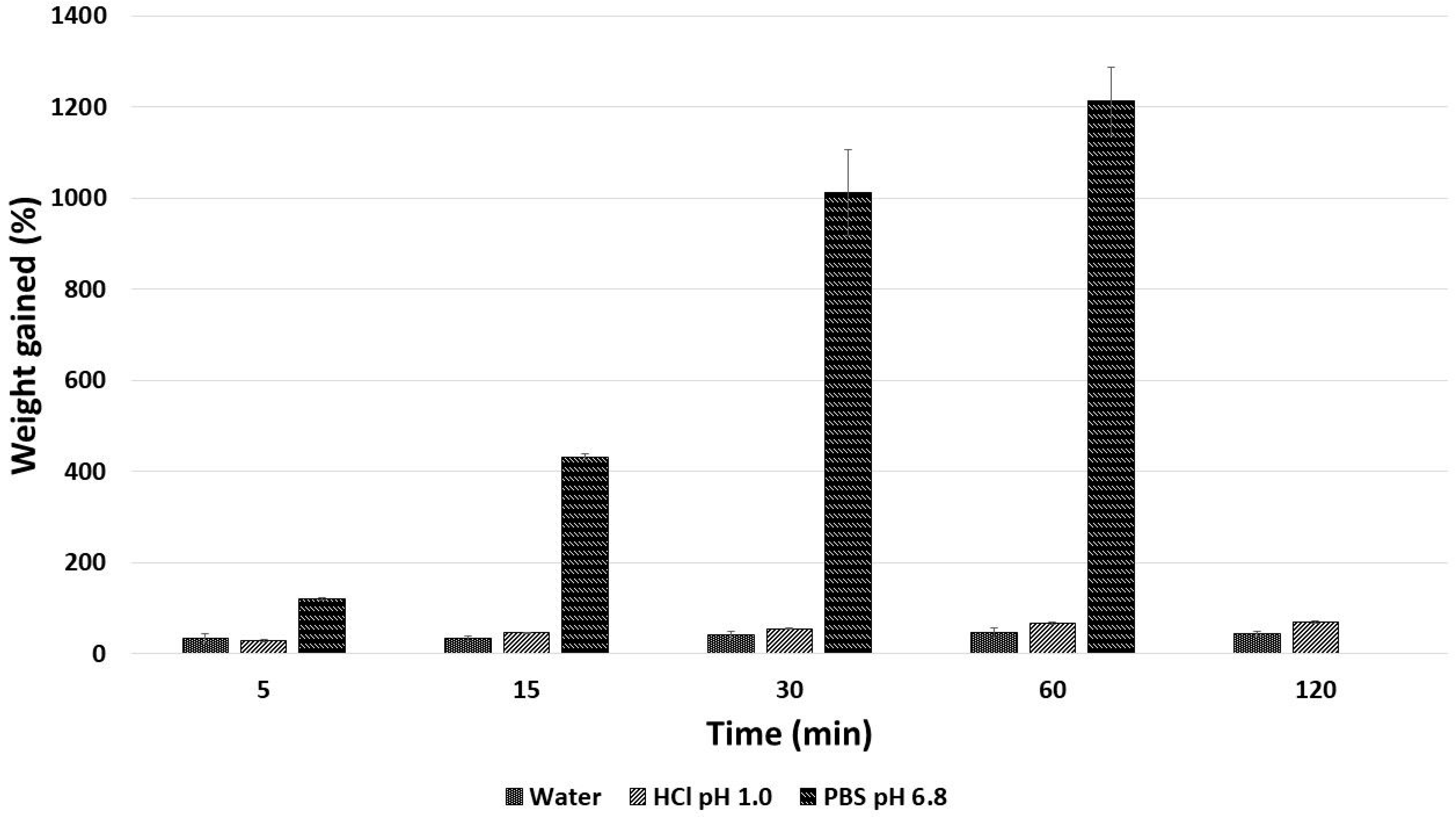

Swelling Test

4.2.6. Production of the Biscuits

4.2.7. Biscuits Characterisation

Proximate Composition

Extraction of the Phenolic Fraction from the Biscuits

Total Phenolic Content and Antioxidant Activity of the Biscuits

Fatty Acids Methyl Esters (FAME) Analysis

Extraction and Analysis of Bitter Compounds

4.2.8. Consumer Evaluation

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Oba, Y.; Urai, M.; Wu, J.; Tomizawa, M.; Kawagishi, H.; Hashimoto, K. Bitter compounds in two Tricholoma species, T. aestuans and T. virgatum. J. Antibiot. 2020, 73, 697–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Tong, H. An overview of bitter compounds in foodstuffs: Classifications, evaluation methods for sensory contribution, separation and identification techniques, and mechanism of bitter taste transduction. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2023, 22, 187–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Grierson, W.X. Biosynthesis, distribution, nutritional and organoleptic properties of bitter compounds in fruit and vegetables. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 1934–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziaikin, E.; Tello, E.; Peterson, D.G.; Niv, M.Y. BitterMasS: Predicting bitterness from mass spectra. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 10537–10547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaudette, N.J.; Pickering, G.J. Modifying bitterness in functional food systems. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2013, 53, 464–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, M.B.C.; Schmidt, F.L.; Rappsilber, J.; Gibson, B.; Wietstock, P.C. Addition of hop (Humulus Lupulus L.) bitter acids yields modification of malt protein aggregate profiles during wort boiling. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 5700–5711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mennella, I.; Fogliano, V.; Ferracane, R.; Arlorio, M.; Pattarino, F.; Vitaglione, P. Microencapsulated bitter compounds (from Gentiana lutea) reduce daily energy intakes in humans. Br. J. Nutr. 2016, 116, 1841–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Ao, W.; Gao, M.; Wu, L.; Pei, Y.; Liu, S.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, F.; Sun, Q.; Liu, J.; et al. Bitter taste TAS2R14 activation by intracellular tastants and cholesterol. Nature 2024, 631, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S.S.; Liggett, S.B. Taste and smell GPCRs in the lung: Evidence for a previously unrecognized widespread chemosensory system. Cell. Signal. 2018, 41, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrens, M.; Meyerhof, W. A role for taste receptors in (neuro)endocrinology? J. Neuroendocrinol. 2019, 31, e12691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloxham, C.J.; Foster, S.R.; Thomas, W.G. A bitter taste in your heart. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamila, T.; Agnieszka, K. An update on extra-oral bitter taste receptors. J. Transl. Med. 2021, 19, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Abbasi, B.H.; Ihsan-ul-haq. Production of commercially important secondary metabolites and antioxidant activity in cell suspension cultures of Artemisia absinthium L. Ind. Crops Prod. 2013, 49, 400–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurrell, J.A.; Puentes, J.P.; Arenas, P.M. Medicinal plants with cholesterol-lowering effect marketed in the Buenos Aires-La Plata conurbation, Argentina: An urban ethnobotany study. Ethnobiol. Conserv. 2015, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szopa, A.; Pajor, J.; Klin, P.; Rzepiela, A.; Elansary, H.O.; Al-Mana, F.A.; Mattar, M.A.; Ekiert, H. Artemisia absinthium L.—Importance in the History of Medicine, the Latest Advances in Phytochemistry and Therapeutical, Cosmetological and Culinary Uses. Plants 2020, 9, 1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talmon, M.; Bosso, L.; Quaregna, M.; Lopatriello, A.; Rossi, S.; Gavioli, D.; Marotta, P.; Caprioglio, D.; Boldorini, R.; Miggiano, R.; et al. Anti-inflammatory activity of absinthin and derivatives in human bronchoepithelial cells. J. Nat. Prod. 2020, 83, 1740–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi-Rad, J.; Herrera-Bravo, J.; Semwal, P.; Painuli, S.; Badoni, H.; Ezzat, S.M.; Farid, M.M.; Merghany, R.M.; Aborehab, N.M.; Salem, M.A.; et al. Artemisia spp.: An update on its chemical composition, Pharmacological and Toxicological Profiles. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 5628601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batiha, G.E.S.; Olatunde, A.; El-mleeh, A.; Hetta, H.F.; Al-rejaie, S.; Alghamdi, S.; Zahoor, M.; Beshbishy, A.M.; Murata, T.; Zaragoza-bastida, A.; et al. Bioactive compounds, pharmacological actions, and pharmacokinetics of wormwood (Artemisia absinthium). Antibiotics 2020, 9, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talmon, M.; Rossi, S.; Lim, D.; Pollastro, F.; Palattella, G.; Ruffinatti, F.A.; Marotta, P.; Boldorini, R.; Genazzani, A.A.; Fresu, L.G. Absinthin, an agonist of the bitter taste receptor hTAS2R46, uncovers an ER-to-mitochondria Ca2–shuttling event. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 12472–12482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, S.; Jafari, S.M.; Ebrahimi, M.; Kijpatanasilp, I.; Assatarakul, K. A decade overview and prospect of spray drying encapsulation of bioactives from fruit products: Characterization, food application and in vitro gastrointestinal digestion. Food Hydrocolloids 2023, 134, 108068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, M. Overview of Encapsulation and Controlled Release. In Handbook of Encapsulation and Controlled Release; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadziński, P.; Froelich, A.; Jadach, B.; Wojtyłko, M.; Tatarek, A.; Białek, A.; Krysztofiak, J.; Gackowski, M.; Otto, F.; Osmałek, T. Ionotropic gelation and chemical crosslinking as methods for fabrication of modified-release gellan gum-based drug delivery systems. Pharmaceutics 2022, 15, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabbani, N.R.; Seville, P.C. The influence of formulation components on the aerosolisation properties of spray-dried powders. J. Control. Rel. 2005, 110, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosnik, A.; Seremeta, K.P. Advantages and challenges of the spray-drying technology for the production of pure drug particles and drug-loaded polymeric carriers. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2015, 223, 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Pharmacopoeia. European Pharmacopoeia, 11th ed.; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- López-Lilao, A.; Forner, V.S.; Gasch, G.M.; Gimeno, E.M. Particle size distribution: A key factor in estimating powder dustiness. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2017, 14, 975–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, A.; Cathala, B. Smart swelling biopolymer microparticles by a microfluidic approach: Synthesis, in situ encapsulation and controlled release. Coll. Surf. B Biointerf. 2011, 82, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffman, A.S. Hydrogels for biomedical applications. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2012, 64, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma-Morales, M.; Melgar-Locatelli, S.; Castilla-Ortega, E.; Rodríguez-Pérez, C. How Healthy Is It to Fortify Cocoa-Based Products with Cocoa Flavanols? A Comprehensive Review. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toprakçı, G.; Toprakçı, İ.; Şahin, S. Alginate Microbeads for Trapping Phenolic Antioxidants in Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.): Multivariate Optimization Based on Bioactive Properties and Morphological Measurements. Gels 2025, 11, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boskou, D.; Blekas, G.; Tsimidou, M. 4-Olive Oil Composition. In Olive Oil, 2nd ed.; Boskou, D., Ed.; AOCS Press: Champaign, IL, USA, 2006; pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aberham, A.; Cicek, S.S.; Schneider, P.; Stuppner, H. Analysis of sesquiterpene lactones, lignans, and flavonoids in wormwood (Artemisia absinthium L.) using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)-mass spectrometry, reversed phase HPLC, and HPLC-Solid phase extraction-nuclear magnetic resonance. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 10817–10823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Disca, V.; Jaouhari, Y.; Carrà, F.; Martoccia, M.; Travaglia, F.; Locatelli, M.; Bordiga, M.; Arlorio, M. Effect of carbohydrase treatment on the dietary fibers and bioactive compounds of cocoa bean shells (CBSs). Foods 2024, 13, 2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaouhari, Y.; Ferreira-Santos, P.; Disca, V.; Oliveira, H.; Martoccia, M.; Travaglia, F.; Gullón, B.; Mateus, N.; Coïsson, J.D.; Bordiga, M. Carbohydrases treatment on blueberry pomace: Influence on chemical composition and bioactive potential. LWT 2024, 206, 116573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly, L.M.; He, F.; Rodriguez-Zas, S.L.; Southey, B.R.; Hoke, J.M.; Davenport, G.M.; de Godoy, M.R.C. Effects of graded inclusion levels of raw garbanzo beans on apparent total tract digestibility, fecal quality, and fecal fermentative end-products and microbiota in extruded feline diets. J. Anim. Sci. 2021, 99, skab297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Locatelli, M.; Coïsson, J.D.; Travaglia, F.; Cereti, E.; Garino, C.; D’Andrea, M.; Martelli, A.; Arlorio, M. Chemotype and genotype chemometrical evaluation applied to authentication and traceability of “tonda Gentile Trilobata” hazelnuts from Piedmont (Italy). Food Chem. 2011, 129, 1865–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Appearance | Odor | Taste | Flavor | Texture | Overall Liking | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBs | 2269 a | 2588 a | 2878 b | 2927 b | 2422 a | 2757 a |

| MPBs | 2781 a | 2462 a | 2172 a | 2124 a | 2628 a | 2293 a |

| Formulation | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solvent (%) | 86.7 | 79.7 | 83.9 | 79.7 | 92.9 | 90.8 | 91.3 | 88.8 |

| AAE (%) | 4.4 | 10.2 | 5.4 | 10.2 | 2.3 | 4.6 | 2.9 | 5.6 |

| EC (%) | 8.9 | 10.2 | 10.7 | 10.2 | 4.7 | 4.6 | 5.8 | 5.6 |

| Formulation | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feed rate (mL/min) | 3.8 | 4.0 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 3.8 | 4.1 | 3.9 |

| P nozzle | 30 | 30 | 45 | 45 | 30 | 30 | 45 | 45 |

| T inlet (°C) | 65 | 65 | 65 | 65 | 90 | 90 | 95 | 95 |

| T outlet (°C) | 50 | 46 | 46 | 48 | 61 | 60 | 63 | 64 |

| Tip hole (mm) | 0.7 | 0.7 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Load (%) | 33.3 | 50.0 | 33.3 | 50.0 | 33.3 | 50.0 | 33.3 | 50.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Candiani, A.; Diana, G.; Disca, V.; Jaouhari, Y.; Stampini, M.; Salamone, S.; Pollastro, F.; Baima, J.; Prodam, F.; Tini, S.; et al. Alginate-Based Beads Containing Artemisia absinthium L. Extract as Innovative Ingredients for Baked Products. Gels 2026, 12, 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010043

Candiani A, Diana G, Disca V, Jaouhari Y, Stampini M, Salamone S, Pollastro F, Baima J, Prodam F, Tini S, et al. Alginate-Based Beads Containing Artemisia absinthium L. Extract as Innovative Ingredients for Baked Products. Gels. 2026; 12(1):43. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010043

Chicago/Turabian StyleCandiani, Alessandro, Giada Diana, Vincenzo Disca, Yassine Jaouhari, Margherita Stampini, Stefano Salamone, Federica Pollastro, Jessica Baima, Flavia Prodam, Sabrina Tini, and et al. 2026. "Alginate-Based Beads Containing Artemisia absinthium L. Extract as Innovative Ingredients for Baked Products" Gels 12, no. 1: 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010043

APA StyleCandiani, A., Diana, G., Disca, V., Jaouhari, Y., Stampini, M., Salamone, S., Pollastro, F., Baima, J., Prodam, F., Tini, S., Bertolino, M., Giovannelli, L., Segale, L., Coïsson, J. D., & Arlorio, M. (2026). Alginate-Based Beads Containing Artemisia absinthium L. Extract as Innovative Ingredients for Baked Products. Gels, 12(1), 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010043