Transcatheter Arterial Embolization (TAE) of Uterine Artery with Gelatin Sponge for Cesarean Scar Pregnancy: A Current State of the Art Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Data Collection Strategy

| Reference | Country | Study Design | Sample Size (N) | Age (Years) | Gestational Age (Days) | Embolic Agent | GS Form/Size | MTX Dose/Route | Technical Success Rate, n/N (%) | Clinical Success Rate, n/N (%) | Severe Complication Rate, n/N (%) | Reduced Menstrual Blood Volume, n/N (%) | Menstrual Recovery (Months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pecorino, 2024 [38] | Italy | Retrospective cohort study | 10 | 34 (5.10) | 57.26 (11.83) | GS | particles | - | 10/10 (100%) | 10/10 (100%) | 0/10 (0%) | NR | NR |

| Ma, 2024 [39] | China | Retrospective cohort study | 10 | NR | NR | GS | particles 0.9–1.2 mm | - | 10/10 (100%) | 8/10 (80%) | 0/10 (0%) | NR | NR |

| Rui, 2024 [40] | China | Retrospective cohort study | 39 | 32.8 (3.80) | 46.9 (9.70) | GS | particles 1 mm | - | 39/39 (100%) | 39/39 (100%) | 0/39 (0%) | 9/39 (22.20%) | NR |

| Gao, 2023 [41] | China | Retrospective cohort study | 66 | 34.71 (5.91) | 51.57 (8.85) | GS | particles 0.56–0.71 mm and 0.71–1 mm | - | 66/66 (100%) | 64/66 (96.97%) | 2/66 (3.03%) Severe vaginal bleeding (n = 2) | NR | 1.26 (0.24) |

| Wang, 2023 [42] | China | Retrospective cohort study | 118 | 31.12 (5.39) | 50.50(42–60) | GS | particles 0.5–1 mm | - | 118/118 (100%) | 109/118 (92.37%) | 7/118 (5.93%) Severe vaginal bleeding (n = 7) | NR | 1.33 (1.17–1.61) |

| Sun, 2023 [43] | China | Prospective cohort study | 22 | 33.72 (3.94) | 48.00 (34–79) | GS | particles 1–1.4 mm | - | 22/22 (100%) | 22/22 (100%) | 1/22 (4.54%) Severe pain (n = 1) | 6/22 (27.27%) | NR |

| Rahman, 2023 [44] | China | Retrospective cohort study | 137 | 30.3 (0.72) | NR | GS | particles | - | 137/137 (100%) | 127/137 (92.7%) | NR | 82/137 (59.85%) | 1.39 (1.02) |

| Hong, 2022 [45] | China | Retrospective cohort study | 160 | 33.1 (5.1) | 51.1 (12.3) | GS | particles 1–2 mm | - | 160/160 (100%) | 158/160 (98.75%) | NR | NR | 1.43 (0.43) |

| Gu, 2022 [46] | China | Retrospective cohort study | 54 | 31.4 (3.9) | 51.91 (21.78) | GS | particles 0.56–0.71 mm | - | 54/54 (100%) | 54/54 (100%) | NR | 32/54 (59.30%) | 1.12 (0.29) |

| Zhou, 2022 [47] | China | Retrospective cohort study | 85 | 32.7 (5.4) | 53.2 (13.8) | GS | particles 1–2 mm | - | 85/85 (100%) | 75/85 (88.23%) | 7/85 (8.23%) Severe vaginal bleeding (n = 6) Leg embolization (n = 1) | NR | NR |

| Shao, 2022 [48] | China | Retrospective cohort study | 101 | 33.5 (9.2) | 55.2 (15.9) | GS | particles | - | 101/101 (100%) | 95/101 (94.06%) | 0/101 (0%) | 19/101 (18.9%) | NR |

| Wang, 2021 [49] | China | Retrospective cohort study | 23 | 29.2 (3.60) | NR | GS | NR | - | 23/23 (100%) | 21/23 (91.3%) | 2/23 (8.7%) Massive hemorrhage (n = 2) | NR | NR |

| Yin, 2020 [50] | China | Retrospective cohort study | 42 | NR | NR | GS | particles and strips | - | 42/42 (100%) | 40/42 (95.24%) | NR | NR | NR |

| Fang, 2020 [51] | China | Case series | 32 | 30.39 (5.78) | 68.05 (23.29) | GS | particles | - | 32/32 (100%) | 14/32 (43.75%) | 5/32 (15.62%) Massive hemorrhage (n = 5) | NR | NR |

| Li, 2020 [52] | China | Retrospective cohort study | 169 | 33.58(4.88) | NR | GS | particles 0.56–0.71 mm and 1 mm | - | 169/169 (100%) | 162/169 (96%) | 5/169 (2.96%) Massive vaginal bleeding (n = 2) Amenorrhea (n = 2) Bacteremia (n = 1) | 101/169 (59.70%) | NR |

| Ou, 2020 [53] | China | Prospective cohort study | 65 | 34 (4.40) | 52.29 (10.32) | GS | particles 0.5–1 mm | - | 65/65 (100%) | 64/65 (98.46%) | 0/65 (0%) | NR | NR |

| Qiu, 2019 [54] | China | Retrospective cohort study | 62 | 32.24 (4.91) | - | GS | particles 0.9–1.2 mm | - | 62/62 (100%) | 55/62 (88.71%) | 4/62 (6.45%) Massive vaginal bleeding (n = 4) | NR | 1.17 (0.25) |

| Xiao, 2019 [55] | China | Retrospective case-control study | 35 | 32.67(6.96) | 51.50 (44–62) | GS | particles | - | 35/35 (100%) | 35/35 (100%) | 0/35 (0%) | NR | NR |

| Zhang, 2019 [56] | China | Retrospective cohort study | 46 | 32.5 (4.70) | 48.7 (9.80) | GS | particles | - | 46/46 (100%) | 46/46 (100%) | 0/46 (0%) | NR | NR |

| Tumenjargal, 2018 [57] | Japan | Retrospective cohort study | 33 | 33 (4.20) | 43.90 (8.30) | GS | particles | - | 33/33 (100%) | 29/33 (87.9%) | 0/33 (0%) | NR | 1.2 (0.64) |

| Gao, 2018 [58] | China | Retrospective cohort study | 57 | 33.46(4.47) | 54.25 (11.60) | GS | NR | - | 57/57 (100%) | 57/57 (100%) | 0/57 (0%) | NR | NR |

| Guo, 2018 [5] | China | Retrospective cohort study | 51 | 32.21(5.68) | 54.82 (9.27) | GS | particles | - | 51/51 (100%) | 41/51 (80.4%) | 0/51 (0%) | NR | NR |

| Hong, 2017 [59] | China | Retrospective cohort study | 67 | 31.74(3.69) | NR | GS | particles | - | 67/67 (100%) | 59/67 (88.06%) | 3/67 (4.48%) Severe fever (n = 3) | NR | 1.16 (0.20) |

| Ma, 2017 [33] | China | Retrospective cohort study | 22 | 32 (29–35) | 49.00 (42–63) | GS | particles 0.56–0.71 mm | - | 22/22 (100%) | 19/22 (86.36%) | 2/22 (9.09%) Severe vaginal bleeding (n = 2) | 2/22 (8.30%) | 2 (1.50–2.83) |

| Chen, 2017 [12] | China | Retrospective cohort study | 49 | 33.7 (4.80) | NR | GS | particles 1 mm | - | 49/49 (100%) | 47/49 (95.92%) | 2/49 (4.08%) Massive hemorrhage (n = 2) | 35/49 (71.40%) | NR |

| Liu, 2016 [60] | China | Retrospective cohort study | 38 | NR | NR | GS | particles | - | 38/38 (100%) | 38/38 (100%) | NR | NR | NR |

| Qi, 2015 [27] | China | Case series | 28 | 31.68 (4.58) | 54.33 (17.51) | GS | particles 1–2 mm | - | 28/28 (100%) | 25/28 (89.3%) | 5/28 (17.86%) Massive hemor-rhage (n = 4) Non target embolization (n = 1) | NR | 0.67–1.50 |

| Qian, 2015 [61] | China | Prospective clinical study | 66 | 31.39 (4.22) | 51.66 (9.35) | GS | particles | - | 66/66 (100%) | 63/66 (95.45%) | 1/66 (1.51%) Hysterectomy due to hemorrhagic shock (n = 1) | NR | NR |

| Zhu, 2016 [62] | China | Retrospective cohort study | 46 | 31.4 (5.10) | 60.6 (16.40) | GS | particles | - | 46/46 (100%) | 45/46 (97.83%) | 2/46 (4.35%) Severe fever (n = 1) Massive vaginal bleeding (n = 1) | NR | 1.06 (0.36) |

| Wang, 2024 [63] | China | Retrospective cohort study | 45 | 31.56 (2.22) | 54.25 (15.54) | GS+ MTX | particles | MTX 100 mg ia | 45/45 (100%) | 45/45 (100%) | 0/45 (0%) | 3/45 (6.67%) | 1.63 (0.16) |

| Sun, 2023 [43] | China | Prospective cohort study | 22 | 32.67 (4.04) | 46 (35–90) | GS + MTX | particles 1–1.4 mm | MTX 1 mg/Kg ia | 22/22 (100%) | 22/22 (100%) | 2/22 (9.09%) Severe pain (n = 2) | 9/22 (40.91%) | NR |

| Baffero, 2023 [64] | Italy | Retrospective cohort study | 11 | 35 (29–38) | 45 (41–49) | GS + MTX | particles 0.5–1 mm | MTX 50 mg ia | 11/11 (100%) | 11/11 (100%) | 0/11 (0%) | NR | 1.43 (1–1.73) |

| Tan, 2021 [65] | China | Prospective non-randomized study | 36 | 33.10(3.90) | 54.44 (9.50) | GS + MTX | particles 0.56–1.4 mm | MTX 50 mg ia | 36/36 (100%) | 35/36 (97.22%) | 2/36 (5.55%) Severe blood loss (n = 1) Pelvic infection (n = 1) | NR | NR |

| Cao, 2021 [66] | China | Retrospective cohort study | 53 | 34.79 (3.43) | 49.43 (6.38) | GS + MTX | particles 1–1.4 mm | MTX 50 mg ia | 53/53 (100%) | 52/53 (98.11%) | 1/53 (1.89%) Heavy vaginal bleeding (n = 1) | NR | NR |

| Cheng, 2020 [67] | China | Retrospective cohort study | 61 | 33.50 (0.60) | 52 (42–58) | GS + MTX | particles 1 mm | MTX 200 mg ia | 61/61 (100%) | 50/61 (82%) | 3/61 (4.91%) Laparotomy due to hemorrhage or bladder injury (n = 3) | NR | NR |

| Lou, 2020 [68] | China | Retrospective cohort study | 53 | 33 (3.60) | 47 (8.40) | MTX → GS * | particles | MTX 50 mg/m2 BSA ia or im | 53/53 (100%) | 52/53 (98.11%) | 3/53 (5.66%) Severe bleeding (n = 2) Massive hemorrhage (n = 1) | NR | 1.75 (1.1) |

| Wang, 2019 [69] | China | Retrospective cohort study | 38 | 31.78 (2.57) | 55.04 (10.76) | GS + MTX | particles | MTX 25 mg ia | 38/38 (100%) | 38/38 (100%) | 6/38 (15.79%) DVT (n = 2) Hypo- or a-menorrhea (n = 3) Ovarian failure (n = 1) | NR | NR |

| Fei, 2019 [70] | China | Retrospective cohort study | 26 | 31.4 (4.40) | NR | GS + MTX | particles | MTX 50 mg ia | 26/26 (100%) | 26/26 (100%) | 0/26 (0%) | NR | NR |

| Gao, 2018 [58] | China | Retrospective cohort study | 36 | 32.18(5.65) | 55.58 (9.82) | GS + MTX | NR | MTX 150 mg ia | 36/36 (100%) | 36/36 (100%) | 0/36 (0%) | NR | NR |

| Li, 2018 [71] | China | Retrospective cohort study | 383 | 32.3 (4.90) | NR | GS + MTX | particles 0.5–1 mm | MTX 50–70 mg ia | 377/383 (98.4%) | 379/383 (99%) | 16/383 (4.18%) Massive hemorrhage (n = 11) Severe fever (n = 5) | 167/383 (43.52%) | NR |

| Xiao, 2018 [72] | China | Retrospective cohort study | 102 | 33.1 (4.60) | 51.19 (11.13) | GS + MTX | particles 0.7–1 mm | MTX 100–150 mg ia | 102/102 (100%) | 98/102 (96.08%) | 4/102 (3.92%) Laparotomy (n = 4) | NR | NR |

| Xiao, 2017 [73] | China | Retrospective cohort study | 45 | 31.87 (4.50) | 48.76 (8.63) | GS + MTX | particles 0.5–1 mm | MTX 50 mg ia | 45/45 (100%) | 44/45 (97.78%) | 6/45 (13.33%) Heavy vaginal bleeding (n = 1) Severe pain (n = 2) Amenorrhea (n = 3) | 8/45 (16.67%) | 1.40 (0.61) |

| Yang, 2016 [74] | China | Retrospective cohort study | 77 | NR | NR | GS + MTX | particles | MTX 50 mg ia | 77/77 (100%) | 77/77 (100%) | 0/77 (0%) | NR | NR |

| Du, 2015 [75] | China | Retrospective case-control study | 175 | 32.44(4.60) | 54.05 (14.04) | GS + MTX | particles 1.4–2 mm | MTX 1 mg/Kg ia | 175/175 (100%) | 169/175 (96.57%) | 6/175 (3.43%) Massive hemorrhage (n = 6) | NR | NR |

| Huang, 2015 [76] | China | Retrospective cohort study | 31 | 32.42(5.94) | 42.12 (6.32) | GS + MTX | particles 0.5–1 mm | MTX 50 mg/m2 BSA ia | 31/31 (100%) | 31/31 (100%) | 0/31 (0%) | NR | NR |

| Sun, 2015 [77] | China | Retrospective cohort study | 15 | 31.70(1.70) | 43.70(1.40) | GS + MTX | particles | MTX 100 mg ia | 15/15 (100%) | 11/15 (73.33%) | 4/15 (26.67%) Severe vaginal bleeding (n = 4) | NR | NR |

| Wang, 2015 [78] | China | Prospective randomized controlled trial | 24 | 29.96 (4.14) | 51.90(2.90) | GS + MTX | particles | MTX 25 mg ia | 24/24 (100%) | 20/24 (83.33%) | NR | NR | NR |

| Guo, 2015 [79] | China | Case series | 50 | NR | 56.78 (17.43) | GS ± MTX | particles 1–2 mm | MTX 50 mg ia | 50/50 (100%) | 42/50 (84%) | 5/50 (10%) Severe vaginal bleeding (n = 4) Amenorrhea (n = 1) | NR | NR |

| Qi, 2015 [27] | China | Case series | 22 | 31.68 (4.58) | 59.86 (17.67) | GS + MTX | particles 1–2 mm | MTX 50 mg ia | 22/22 (100%) | 17/22 (77.3%) | 1/22 (4.54%) Hysterotomy (n = 1) | NR | 0.67–1.50 |

| Cao, 2018 [80] | China | Retrospective cohort study | 101 | 32.98 (4.96) | NR | GS + PVA | particles | - | 101/101 (100%) | 99/101 (98.01%) | 4/101 (3.96%) Massive hemorrhage (n = 2) Amenorrhea (n = 2) | 60/101 (59.40%) | 1.48 (0.9) |

3. Gelatin Sponge Preparation Methods

3.1. Source and Processing Considerations

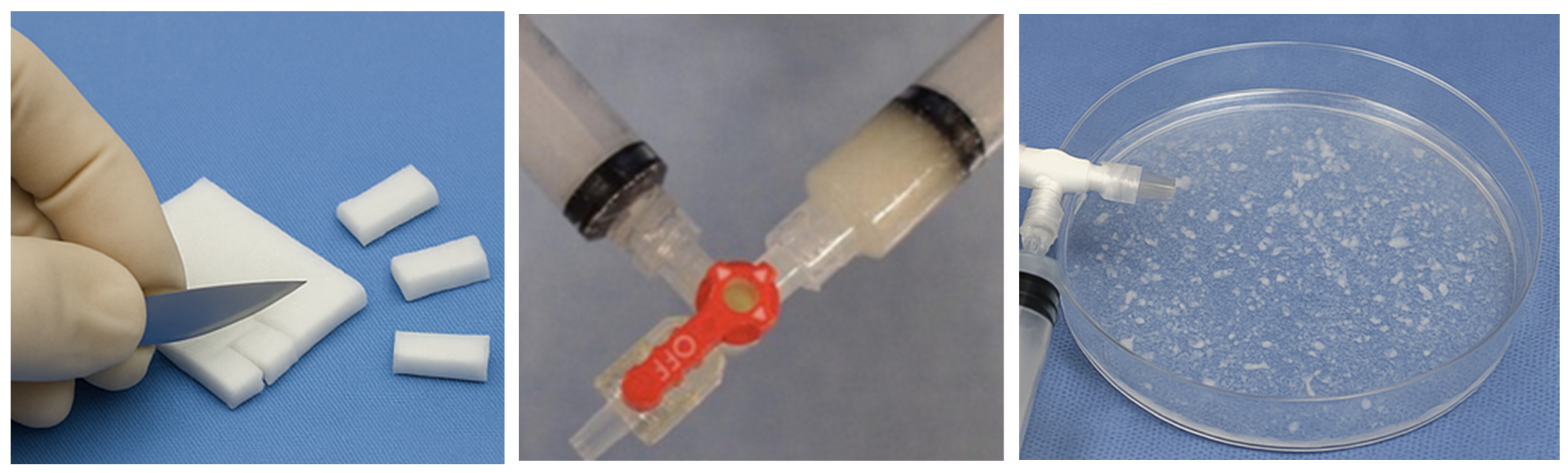

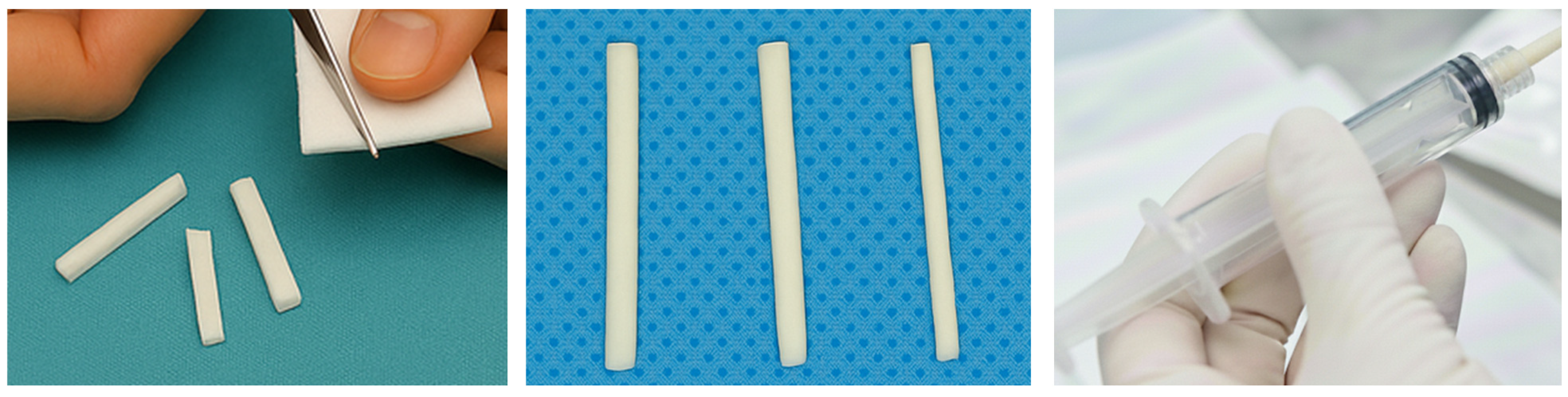

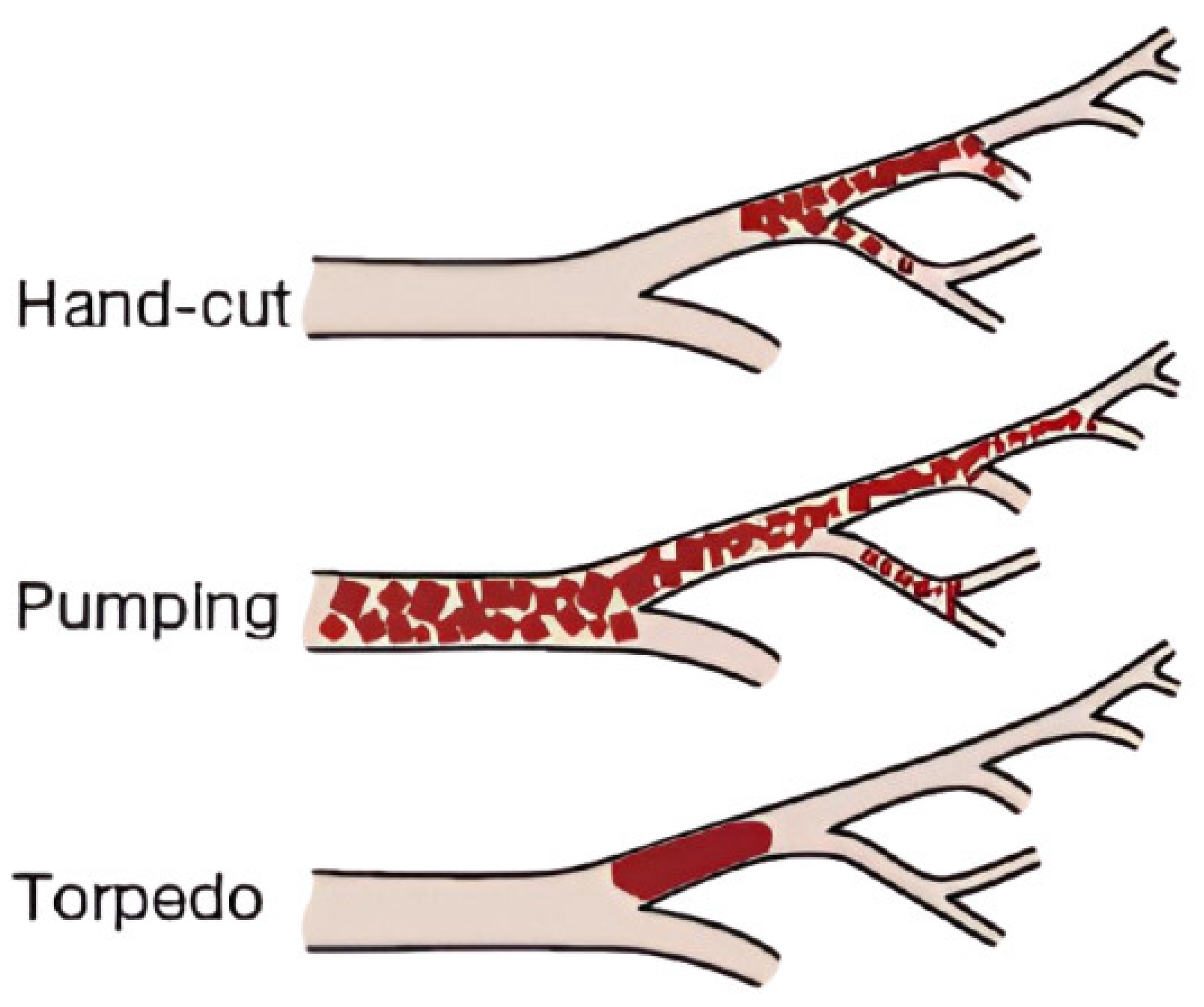

3.2. General Preparation Techniques in Embolotherapy

- -

- Hand-Cut Method (Pledgets):

- -

- Pumping Method (Slurry):

- -

- Torpedo Method:

3.3. Clinical Implications in Uterine Artery Embolization for Cesarean Scar Pregnancy

4. Technical Aspects of Uterine Artery Embolization (UAE)

5. Efficacy Outcomes

6. Safety Outcomes

7. Limitations and Future Perspectives

- -

- CSP type/classification, gestational age, and baseline β-hCG;

- -

- Embolization strategy (bilateral vs. unilateral; target level);

- -

- Catheter/microcatheter and endpoint definition (e.g., near stasis vs. complete stasis);

- -

- GS brand (if stated), preparation method, intended particle/cube size, solvent (contrast/saline), and injection technique/pressure;

- -

- Adjuncts: MTX (route and dose), other embolics (type and size);

- -

- D&C timing;

- -

- Definitions of technical/clinical success and the assessment window;

- -

- Complications with standardized grading (SIR);

- -

- Follow-up duration, menstrual outcomes definitions, and subsequent pregnancy/live-birth outcomes (if collected).

8. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BSA | Body Surface Area |

| CSD | Cesarean Scar Defect |

| CSP | Cesarean Scar Pregnancy |

| D&C | Dilation and Curettage |

| DSA | Digital Subtraction Angiography |

| DVT | Deep Vein Thrombosis |

| GS | Gelatin Sponge |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| i.a. | intra-arterial (administration) |

| i.m. | intramuscular (administration) |

| MBV | Menstrual Blood Volume |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| MTX | Methotrexate |

| NSAIDs | Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs |

| PVA | Polyvinyl Alcohol |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| RMBV | Reduced Menstrual Blood Volume |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SIR | Society of Interventional Radiology |

| TAE | Transcatheter Arterial Embolization |

| TRA | Transradial Access |

| UAE | Uterine Artery Embolization |

| UFE | Uterine Fibroid Embolization |

References

- Larsen, J.V.; Solomon, M.H. Pregnancy in a Uterine Scar Sacculus—An Unusual Cause of Postabortal Haemorrhage. A Case Report. S. Afr. Med. J. Suid-Afr. Tydskr. Vir Geneeskd. 1978, 53, 142–143. [Google Scholar]

- Zahálková, L.; Kacerovský, M. Cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy. Ceska Gynekol. 2016, 81, 414–419. [Google Scholar]

- Grechukhina, O.; Deshmukh, U.; Fan, L.; Kohari, K.; Abdel-Razeq, S.; Bahtiyar, M.O.; Sfakianaki, A.K. Cesarean Scar Pregnancy, Incidence, and Recurrence: Five-Year Experience at a Single Tertiary Care Referral Center. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 132, 1285–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timor-Tritsch, I.E.; Monteagudo, A.; Cali, G.; Vintzileos, A.; Viscarello, R.; Al-Khan, A.; Zamudio, S.; Mayberry, P.; Cordoba, M.M.; Dar, P. Cesarean Scar Pregnancy is a Precursor of Morbidly Adherent Placenta. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 44, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Yu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Song, X. Clinical Efficacy and Safety of Uterine Artery Embolization (UAE) versus Laparoscopic Cesarean Scar Pregnancy Debridement Surgery (LCSPDS) in Treatment of Cesarean Scar Pregnancy. Med. Sci. Monit. Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 2018, 24, 4659–4666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM); Miller, R.; Gyamfi-Bannerman, C.; Publications Committee. Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Consult Series #63: Cesarean Scar Ectopic pregnancy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 227, B9–B20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, M.E.; Keefe, N.; Caridi, T.; Kohi, M.; Salazar, G. Interventional Radiology in Obstetrics and Gynecology: Updates in Women’s Health. Radiogr. Rev. Publ. Radiol. Soc. N. Am. Inc 2023, 43, e220039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, M.; Mikes, B.A. Uterine Fibroid Embolization. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, S.; Zhu, L.; Jin, L.; Gao, J.; Chen, C. Uterine Artery Embolization in Cesarean Scar Pregnancy: Safe and Effective Intervention. Chin. Med. J. 2014, 127, 2322–2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawroth, F.; Foth, D.; Wilhelm, L.; Schmidt, T.; Warm, M.; Römer, T. Conservative Treatment of Ectopic Pregnancy in a Cesarean Section Scar with Methotrexate: A Case Report. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2001, 99, 135–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayoglu Tekin, Y.; Mete Ural, U.; Balık, G.; Ustuner, I.; Kır Şahin, F.; Güvendağ Güven, E.S. Management of Cesarean Scar Pregnancy with Suction Curettage: A Report of Four Cases and Review of the Literature. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2014, 289, 1171–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Zhou, J.; Wang, H.; Tan, W.; Yao, M.; Wang, X. The Treatment of Cesarean Scar Pregnancy with Uterine Artery Embolization and Curettage as Compared to Transvaginal Hysterotomy. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2017, 214, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.-T.; Chen, Y.-C.; Chen, M.; Chang, Y.-J.; Yang, S.-H.; Tsai, H.-D.; Wu, C.-H. Reproductive Outcomes of Cesarean Scar Pregnancies Treated with Uterine Artery Embolization Combined with Curettage. Taiwan. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 61, 601–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; Wang, W.; Zhang, Z.; Cheng, S.; Cheng, J.; Fu, L.; Gao, F. Clinical Investigation of Fertility After Uterine Artery Embolization Combined with Dilation and Curettage(D&C) or D&C Alone for Cesarean Scar Pregnancies. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. X 2025, 26, 100379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minici, R.; Venturini, M.; Fontana, F.; Guzzardi, G.; Pingitore, A.; Piacentino, F.; Serra, R.; Coppola, A.; Santoro, R.; Laganà, D. Efficacy and Safety of Ethylene-Vinyl Alcohol (EVOH) Copolymer-Based Non-Adhesive Liquid Embolic Agents (NALEAs) in Transcatheter Arterial Embolization (TAE) of Acute Non-Neurovascular Bleeding: A Multicenter Retrospective Cohort Study. Medicina 2023, 59, 710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minici, R.; Guzzardi, G.; Venturini, M.; Fontana, F.; Coppola, A.; Spinetta, M.; Piacentino, F.; Pingitore, A.; Serra, R.; Costa, D.; et al. Transcatheter Arterial Embolization (TAE) of Cancer-Related Bleeding. Medicina 2023, 59, 1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonemitsu, T.; Kawai, N.; Sato, M.; Sonomura, T.; Takasaka, I.; Nakai, M.; Minamiguchi, H.; Sahara, S.; Iwasaki, Y.; Naka, T.; et al. Comparison of Hemostatic Durability Between N-Butyl Cyanoacrylate and Gelatin Sponge Particles in Transcatheter Arterial Embolization for Acute Arterial Hemorrhage in a Coagulopathic Condition in a Swine Model. Cardiovasc. Interv. Radiol. 2010, 33, 1192–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minici, R.; Fontana, F.; Venturini, M.; Guzzardi, G.; Siciliano, A.; Piacentino, F.; Serra, R.; Coppola, A.; Guerriero, P.; Apollonio, B.; et al. Transcatheter Arterial Embolization (TAE) in the Management of Bleeding in the COVID-19 Patient. Medicina 2023, 59, 1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minici, R.; Serra, R.; Giurdanella, M.; Talarico, M.; Siciliano, M.A.; Carrafiello, G.; Laganà, D. Efficacy and Safety of Distal Radial Access for Transcatheter Arterial Chemoembolization (TACE) of the Liver. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alali, M.; Cao, C.; Shin, J.H.; Jeon, G.; Zeng, C.H.; Park, J.-H.; Aljerdah, S.; Aljohani, S. Preliminary Report on Embolization with Quick-Soluble Gelatin Sponge Particles for Angiographically Negative Acute Gastrointestinal Bleeding. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 6438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minici, R.; Mercurio, M.; Guzzardi, G.; Venturini, M.; Fontana, F.; Brunese, L.; Guerriero, P.; Serra, R.; Piacentino, F.; Spinetta, M.; et al. Transcatheter Arterial Embolization for Bleeding Related to Pelvic Trauma: Comparison of Technical and Clinical Results between Hemodynamically Stable and Unstable Patients. Tomography 2023, 9, 1660–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minici, R.; Fontana, F.; Venturini, M.; Guzzardi, G.; Piacentino, F.; Spinetta, M.; Bertucci, B.; Serra, R.; Costa, D.; Ielapi, N.; et al. A Multicenter Retrospective Cohort Study Evaluating the Clinical Outcomes of Patients with Coagulopathy Undergoing Transcatheter Arterial Embolization (TAE) for Acute Non-Neurovascular Bleeding. Medicina 2023, 59, 1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loffroy, R.; Comby, P.-O.; Falvo, N.; Pescatori, L.; Nakaï, M.; Midulla, M.; Chevallier, O. Transcatheter Arterial Embolization Versus Surgery for Uncontrolled Peptic Ulcer Bleeding: Game is Over. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2019, 9, 144–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minici, R.; Guerriero, P.; Fontana, F.; Venturini, M.; Guzzardi, G.; Piacentino, F.; Coppola, A.; Spinetta, M.; Siciliano, A.; Serra, R.; et al. Endovascular Treatment of Visceral Artery Pseudoaneurysms with Ethylene-Vinyl Alcohol (EVOH) Copolymer-Based Non-Adhesive Liquid Embolic Agents (NALEAs). Medicina 2023, 59, 1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohiltea, R.; Ducu, I.; Mihai, B.; Iordache, A.-M.; Dorobat, B.; Vladareanu, E.M.; Iordache, S.-M.; Bohiltea, A.-T.; Bacalbasa, N.; Grigorescu, C.E.A.; et al. Uterine Artery Embolization Combined with Subsequent Suction Evacuation as Low-Risk Treatment for Cesarean Scar Pregnancy. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siskin, G.P.; Shlansky-Goldberg, R.D.; Goodwin, S.C.; Sterling, K.; Lipman, J.C.; Nosher, J.L.; Worthington-Kirsch, R.L.; Chambers, T.P.; UAE Versus Myomectomy Study Group. A Prospective Multicenter Comparative Study Between Myomectomy and Uterine Artery Embolization with Polyvinyl Alcohol Microspheres: Long-Term Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Symptomatic Uterine Fibroids. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2006, 17, 1287–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, F.; Zhou, W.; Wang, M.-F.; Chai, Z.-Y.; Zheng, L.-Z. Uterine Artery Embolization with and Without Local Methotrexate Infusion for the Treatment of Cesarean Scar Pregnancy. Taiwan. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 54, 376–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, J.J.; Golzarian, J. Embolics Review: Current Options and Agents in the Pipeline. Vasc. Dis. Manag. 2023, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Bulman, J.C.; Kim, N.H.; Kaplan, R.S.; Schroeppel DeBacker, S.E.; Brook, O.R.; Sarwar, A. True Costs of Uterine Artery Embolization: Time-Driven Activity-Based Costing in Interventional Radiology Over a 3-Year Period. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 2024, 21, 721–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abada, H.T.; Golzarian, J. Gelatine Sponge Particles: Handling Characteristics for Endovascular Use. Tech. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2007, 10, 257–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khankan, A.A.; Osuga, K.; Hori, S.; Morii, E.; Murakami, T.; Nakamura, H. Embolic Effects of Superabsorbent Polymer Microspheres in Rabbit Renal Model: Comparison with Tris-Acryl Gelatin Microspheres and Polyvinyl Alcohol. Radiat. Med. 2004, 22, 384–390. [Google Scholar]

- Laurent, A. Microspheres and Nonspherical Particles for Embolization. Tech. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2007, 10, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Yang, C.; Shao, X. Efficacy Comparison of Transcatheter Arterial Embolization with Gelatin Sponge and Polyvinyl Alcohol Particles for the Management of Cesarean Scar Pregnancy and Follow-Up Study. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2017, 43, 682–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorrentino, F.; De Feo, V.; Stabile, G.; Tinelli, R.; D’Alterio, M.N.; Ricci, G.; Angioni, S.; Nappi, L. Cesarean Scar Pregnancy Treated by Artery Embolization Combined with Diode Laser: A Novel Approach for a Rare Disease. Medicina 2021, 57, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wozniak, S.; Pyra, K.; Kłudka-Sternik, M.; Czuczwar, P.; Szkodziak, P.; Paszkowski, T.; Sczerbo-Trojanowska, M. Uterine Artery Embolization Using Gelatin Sponge Particles Performed due to Massive Vaginal Bleeding Caused by Ectopic Pregnancy Within a Cesarean Scar: A Case Study. Ginekol. Polska 2013, 84, 966–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchand, G.J.; Masoud, A.T.; Coriell, C.; Ulibarri, H.; Parise, J.; Arroyo, A.; Goetz, S.; Moir, C.; Moberly, A.; Govindan, M. Treatment of Cesarean Scar Ectopic Pregnancy in China with Uterine Artery Embolization-A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 7393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalilzadeh, O.; Baerlocher, M.O.; Shyn, P.B.; Connolly, B.L.; Devane, A.M.; Morris, C.S.; Cohen, A.M.; Midia, M.; Thornton, R.H.; Gross, K.; et al. Proposal of a New Adverse Event Classification by the Society of Interventional Radiology Standards of Practice Committee. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2017, 28, 1432–1437.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecorino, B.; Scibilia, G.; Mignosa, B.; Teodoro, M.C.; Chiofalo, B.; Scollo, P. Dilatation and Curettage after Uterine Artery Embolization versus Methotrexate Injection for the Treatment of Cesarean Scar Pregnancy: A Single-Center Experience. Medicina 2024, 60, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Chen, S.; Xu, W.; Zhang, R.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, L.; Chen, R. Surgical Treatment of Cesarean Scar Pregnancy Based on the Three-Category System: A Retrospective Analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2024, 24, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rui, T.; Wei, H.; Huaibo, J.; Han, M.; Cheung, K.C.P.; Yang, C. Comparation of Abdominal Aortic Balloon Occlusion Versus Uterine Artery Embolization in the Treatment of Cesarean Scar Pregnancy. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1472239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Lu, Y.; Guo, X.; Gao, J.; Wang, W.; Cheng, J.; Fu, L. Complex Blood Supply Patterns in Cesarean Scar Pregnancy: Insights from Digital Subtraction Angiography Imaging. Med. Sci. Monit. Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 2023, 29, e940133-1–e940133-10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yang, B.; Chen, W.; Chen, J. Clinical Efficacy and Re-Pregnancy Outcomes of Patients with Previous Cesarean Scar Pregnancy Treated with Either High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound or Uterine Artery Embolization Before Ultrasound-Guided Dilatation and Curettage: A Retrospective Cohort Study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2023, 23, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Peng, C.; Liu, X.; Lv, Y.; Shen, H.; Xu, Z.; Chen, X.; Jiang, Q. Effects of Lauromacrogol Injection Under Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound Guidance on Cesarean Scar Pregnancy: A Prospective Cohort Study. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2023, 13, 1849–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, J.; Qiu, Y.; Yuan, X.; Kassim, S.H.; Ji, T.; Dai, H. Pituitrin Injection before Hysteroscopic Curettage for Treating Type I Cesarean Scar Pregnancy in Comparison with Uterine Artery Embolization: A Retrospective Study. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. India 2023, 73, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, T.; Chai, Z.; Liu, M.; Zheng, L.; Qi, F. The Efficacy and Health Economics of Different Treatments for Type 1 Cesarean Scar Pregnancy. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 822319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Z.; Jia, P.; Gao, Z.; Gu, W.; Zhao, H.; Zhao, S. Uterine Artery Embolization Combined with Ultrasound-Guided Dilation and Curettage for the Treatment of Cesarean Scar Pregnancy: Efficacy and 5-8-Year Follow-Up Study. J. Interv. Med. 2022, 5, 148–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Feng, X.; Yu, J.; Chai, Z.; Zheng, L.; Qi, F. The Efficacy of Different Treatments for Type 2 Cesarean Scar Pregnancy. Fertil. Steril. 2022, 118, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, M.; Tang, F.; Ji, L.; Hu, M.; Zhang, K.; Pan, J. The Management of Caesarian Scar Pregnancy with or Without a Combination of Methods Prior to Hysteroscopy: Ovarian Reserve Trends and Patient Outcomes. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Hum. Reprod. 2022, 51, 102417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhao, R.; Qian, H.; Lv, H. Pituitrin Local Injection Versus Uterine Artery Embolization in the Management of Cesarean Scar Pregnancy: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2021, 47, 1711–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Huang, S. Clinical Characteristics and Treatment of Different Types of Cesarean Scar Pregnancy. Ginekol. Pol. 2020, 91, 406–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, S.; Zhang, P.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, F.; He, L. A Retrospective Analysis of the Treatment of Cesarean Scar Pregnancy by High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound, Uterine Artery Embolization and Surgery. Front. Surg. 2020, 7, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Niu, H.; Li, J.; Zhang, L.; Qu, Q. Clinical Assessment of Uterine Artery Embolization Combined with Curettage When Treating Patients with Cesarean Scar Pregnancy: A Retrospective Study Of 169 Cases. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2020, 46, 1110–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, J.; Peng, P.; Li, C.; Teng, L.; Liu, X. Assessment of the Necessity of Uterine Artery Embolization During Suction and Curettage for Caesarean Scar Pregnancy: A Prospective Cohort Study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Fu, Y.; Xu, J.; Huang, X.; Yao, G.; Lu, W. Analysis on Clinical Effects of Dilation and Curettage Guided by Ultrasonography Versus Hysteroscopy After Uterine Artery Embolization in the Treatment of Cesarean Scar Pregnancy. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2019, 15, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Cheng, D.; Chen, J.; Yang, J.; Xu, W.; Xie, Q. The Effects of Methotrexate and Uterine Arterial Embolization in Patients with Cesarean Scar Pregnancy: A Retrospective Case-Control Study. Medicine 2019, 98, e14913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Zhou, T.; Li, M.; Sheng, C.; Shou, J. Dilation and Curettage Following Local Sclerotherapy for Cesarean Scar pregnancy. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2019, 12, 730–734. [Google Scholar]

- Tumenjargal, A.; Tokue, H.; Kishi, H.; Hirasawa, H.; Taketomi-Takahashi, A.; Tsushima, Y. Uterine Artery Embolization Combined with Dilation and Curettage for the Treatment of Cesarean Scar Pregnancy: Efficacy and Future Fertility. Cardiovasc. Interv. Radiol. 2018, 41, 1165–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, L.; Hou, Y.-Y.; Sun, F.; Xia, W.; Yang, Y.; Tian, T.; Chen, Q.-F.; Li, X.-C. A Retrospective Comparative Study Evaluating the Efficacy of Adding Intra-Arterial Methotrexate Infusion to Uterine Artery Embolisation Followed by Curettage for Cesarean Scar Pregnancy. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2018, 297, 1205–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Y.; Guo, Q.; Pu, Y.; Lu, D.; Hu, M. Outcome of High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound and Uterine Artery Embolization in the Treatment and Management of Cesarean Scar Pregnancy: A Retrospective Study. Medicine 2017, 96, e7687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Shen, L.; Wang, Q.; Wang, W.; Sun, Z. Uterine Artery Embolization Combined with Curettage vs. Methotrexate Plus Curettage for Cesarean Scar Pregnancy. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2016, 294, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Z.-D.; Huang, L.-L.; Zhu, X.-M. Curettage or Operative Hysteroscopy in the Treatment of Cesarean Scar Pregnancy. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2015, 292, 1055–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Deng, X.; Xiao, S.; Wan, Y.; Xue, M. A Comparison of High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound and Uterine Artery Embolisation for the Management of Caesarean Scar Pregnancy. Int. J. Hyperth. 2016, 32, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Xue, F.; Wang, W. A Combination of Laparoscopy and Bilateral Uterine Artery Occlusion for the Treatment of Type Ii Cesarean Scar Pregnancy: A Retrospective Analysis. J. Int. Med. Res. 2024, 52, 3000605241241010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baffero, G.M.; Busnelli, A.; Ronchi, A.; Somigliana, E.; Bulfoni, A.; Ossola, M.W.; Simone, N.D.; Ferrazzi, E.M. Different Management Strategies for Cesarean Scar Pregnancy: Short-Term Outcomes and Reproductive Prognosis. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Hum. Reprod. 2023, 52, 102607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.-L.; Chen, Y.-M.; Zeng, W.; Meng, Y.; Jiang, L. Local Methotrexate Injection Followed by Dilation and Curettage for Cesarean Scar Pregnancy: A Prospective Non-Randomized Study. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 800610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Qiu, G.; Zhang, P.; Wang, X.; Wu, Q. A Comparison of Transvaginal Removal and Repair of Uterine Defect for Type II Cesarean Scar Pregnancy and Uterine Artery Embolization Combined with Curettage. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 654956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Tian, Q.; Chang, K.-K.; Yi, X.-F. Comparison of the Efficacy and Safety of Different Surgical Strategies for Patients with Type II Cesarean Scar Pregnancy. Reprod. Dev. Med. 2020, 4, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, T.; Gao, Y.; Feng, Y.; Lu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Bai, H. Reproductive Outcomes of Cesarean Scar Pregnancies Pretreated with Methotrexate and Uterine Artery Embolization Prior to Curettage. Taiwan. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 59, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Luo, F.Y.; Xia, Y.D.; Mei, L.; Xie, L.; Liu, H.X. Clinical Analysis of 211 Cases of Cesarean Scar Pregnancy. Clin. Exp. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 46, 948–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, H.; Jiang, X.; Li, T.; Pan, Y.; Guo, H.; Xu, X.; Shu, S. Comparison Of Three Different Treatment Methods For Cesarean Scar Pregnancy. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2019, 15, 1377–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lu, L.; Wang, W.; Sun, J.; Zhang, X.; Huang, X. Retrospective Study of Patients with Cesarean Scar Pregnancies Treated by Uterine Artery Chemoembolization and Curettage. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2018, 143, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, F.-Y.; Xue, X.-H.; Lu, X. Comparison of Five Treatment Strategies for Cesarean Scar Pregnancy. Reprod. Dev. Med. 2018, 2, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Shi, Z.; Zhou, J.; Ye, J.; Zhu, J.; Zhou, X.; Wang, F.; Zhang, S. Cesarean Scar Pregnancy: Comparing the Efficacy and Tolerability of Treatment with High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound and Uterine Artery Embolization. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2017, 43, 640–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Li, S.; Ma, Z.; Jia, Y. Therapeutic Effects of Uterine Artery Embolisation (Uae) and Methotrexate (Mtx) Conservative Therapy Used in Treatment of Cesarean Scar Pregnancy. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2016, 293, 819–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Y.J.; Zhang, X.H.; Wang, L.Q. Risk Factors for Haemorrhage during Suction Curettage after Uterine Artery Embolization for Treating Caesarean Scar Pregnancy: A Case-Control Study. Gynecol. Obstet. Investig. 2015, 80, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Li, Y.; Xi, R.; Chen, Z.; Ying, D.; Li, Z.; Yang, Y. An Application of Uterine Artery Chemoembolization in Treating Cesarean Scar Pregnancy. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2015, 8, 2570–2577. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.-Y.; Xi, X.-W.; Yan, Q.; Qiao, Q.-Q.; Feng, Y.-J.; Zhu, Y.-P. Management of Type II Unruptured Cesarean Scar Pregnancy: Comparison of Gestational Mass Excision and Uterine Artery Embolization Combined with Methotrexate. Taiwan. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 54, 489–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Yang, Z.; Li, Y.; Chen, B.; Wang, J.; Ma, X.; Wang, Y. Conservative Management of Cesarean Scar Pregnancies: A Prospective Randomized Controlled Trial at a Single Center. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2015, 8, 18972–18980. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Guo, M.; Wang, M.; Liu, M.; Qi, F.; Qu, F.; Zhou, J. Management of Cesarean Scar Pregnancy: A Case Series. Chin. Med. Sci. J. 2015, 30, 226–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, G.-S.; Liu, R.-Q.; Liu, Y.-Y.; Liu, J.-W.; Li, L.-P.; Zhang, Q.; Cao, H.-C.; Li, T.-X. Menstruation Recovery in Scar Pregnancy Patients Undergoing UAE and Curettage and Its Influencing Factors. Medicine 2018, 97, e9584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, H.P.; Janda, R. Studies on the Use of Gelatin Sponge or Foam as an Hemostatic Agent in Experimental Liver Resections and Injuries to Large Veins. Ann. Surg. 1946, 124, 952–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, N.I.; Mohd Zubir, A.Z.; Suwandi, A.; Haris, M.S.; Jaswir, I.; Lestari, W. Gelatin-Based Hemostatic Agents for Medical and Dental Application at a Glance: A Narrative Literature Review. Saudi Dent. J. 2022, 34, 699–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cegielski, M.; Izykowska, I.; Podhorska-Okolow, M.; Zabel, M.; Dziegiel, P. Development of Foreign Body Giant Cells in Response to Implantation of Spongostan as a Scaffold for Cartilage Tissue Engineering. Vivo Athens Greece 2008, 22, 203–206. [Google Scholar]

- Gelfoam—An Overview|ScienceDirect Topics. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/pharmacology-toxicology-and-pharmaceutical-science/gelfoam (accessed on 19 December 2025).

- Ohta, S.; Nitta, N.; Watanabe, S.; Tomozawa, Y.; Sonoda, A.; Otani, H.; Tsuchiya, K.; Nitta-Seko, A.; Yamamoto, A.; Takahashi, M.; et al. Gelatin Microspheres: Correlation Between Embolic Effect/Degradability and Cross-Linkage/Particle Size. Cardiovasc. Interv. Radiol. 2013, 36, 1105–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koike, Y.; Takizawa, K.; Ogawa, Y.; Muto, A.; Yoshimatsu, M.; Yagihashi, K.; Nakajima, Y. Transcatheter Arterial Chemoembolization (TACE) or Embolization (TAE) for Symptomatic Bone Metastases as a Palliative Treatment. Cardiovasc. Interv. Radiol. 2011, 34, 793–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamashita, N.; Saitou, K.; Takagi, A.; Maruyama, A. Preparation and Characterization of Gelatin Sponge Millispheres Injectable Through Microcatheters. Med. Devices Evid. Res. 2009, 2, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiga, A.; Yokota, H.; Higashide, T.; Takishima, H.; Omoto, A.; Kubota, Y.; Horikoshi, T.; Uno, T. The Relationship Between Gelatin Sponge Preparation Methods and the Incidence of Intrauterine Synechia Following Uterine Artery Embolization for Postpartum Hemorrhage. Cardiovasc. Interv. Radiol. 2019, 42, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyayama, S.; Yamakado, K.; Anai, H.; Abo, D.; Minami, T.; Takaki, H.; Kodama, T.; Yamanaka, T.; Nishiofuku, H.; Morimoto, K.; et al. Guidelines on the Use of Gelatin Sponge Particles in Embolotherapy. Jpn. J. Radiol. 2014, 32, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghelfi, J.; Marcelin, C.; Buisson, A.; Mathieu, E.; Sentilhes, L.; Thubert, T.; Boizet, A.; Midulla, M.; Kovacsik, H.; Caudron, S.; et al. Embolization with Gelatin Foam in the Management of Vascularized Retained Products of Conception: A Multicenter Study by the French Society of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur. Radiol. 2025, 35, 2499–2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, E.; Riethmuller, D.; Delouche, A.; Sicot, M.; Teyssier, Y.; Finas, M.; Guillaume, B.; Thony, F.; Ferretti, G.; Ghelfi, J. Management of Symptomatic Vascularized Retained Products of Conception by Proximal Uterine Artery Embolization with Gelatin Sponge Torpedoes. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2022, 33, 1313–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takasaka, I.; Kawai, N.; Sato, M.; Sahara, S.; Minamiguchi, H.; Nakai, M.; Ikoma, A.; Nakata, K.; Sonomura, T. A New Soluble Gelatin Sponge for Transcatheter Hepatic Arterial Embolization. Cardiovasc. Interv. Radiol. 2010, 33, 1198–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Shi, G.; Ruan, J. Uterine Necrosis Following Uterine Artery Embolization: Case Report and Literature Review. Gynecol. Pelvic Med. 2022, 5, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stancato-Pasik, A.; Mitty, H.A.; Richard, H.M.; Eshkar, N. Obstetric Embolotherapy: Effect on Menses and Pregnancy. Radiology 1997, 204, 791–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dehbozorgi, A.; Frenette, A.; Alli, A.; Ash, R.; Rohr, A. Uterine Artery Embolization: Background Review, Patient Management, and Endovascular Treatment. J. Radiol. Nurs. 2021, 40, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, C.J.; Rathinam, D.; Manchanda, S.; Srivastava, D.N. Endovascular Uterine Artery Interventions. Indian J. Radiol. Imaging 2017, 27, 488–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keung, J.J.; Spies, J.B.; Caridi, T.M. Uterine Artery Embolization: A Review of Current Concepts. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2018, 46, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandarpa, K.; Machan, L. Handbook of Interventional Radiologic Procedures; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-0-7817-6816-0. [Google Scholar]

- Bulman, J.C.; Ascher, S.M.; Spies, J.B. Current Concepts in Uterine Fibroid Embolization. RadioGraphics 2012, 32, 1735–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, S.C.; Bonilla, S.C.; Sacks, D.; Reed, R.A.; Spies, J.B.; Landow, W.J.; Worthington-Kirsch, R.L. Reporting Standards for Uterine Artery Embolization for the Treatment of Uterine Leiomyomata. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2003, 14, S467–S476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovsepian, D.M.; Siskin, G.P.; Bonn, J.; Cardella, J.F.; Clark, T.W.I.; Lampmann, L.E.; Miller, D.L.; Omary, R.A.; Pelage, J.-P.; Rajan, D.; et al. Quality Improvement Guidelines for Uterine Artery Embolization for Symptomatic Leiomyomata. Cardiovasc. Interv. Radiol. 2004, 27, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; Tsai, J.; Lee, J.M.; Vang, R.; Griffith, J.G.; Wallach, E.E. Effects of Utero-Ovarian Anastomoses on Basal Follicle-Stimulating Hormone Level Change After Uterine Artery Embolization with Tris-Acryl Gelatin Microspheres. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2006, 17, 965–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrowski, P.; Bonczar, M.; Michalczak, M.; Gabryszuk, K.; Bereza, T.; Iwanaga, J.; Zarzecki, M.; Sporek, M.; Walocha, J.; Koziej, M. The Anatomy of the Uterine Artery: A Meta-Analysis with Implications for Gynecological Procedures. Clin. Anat. 2023, 36, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, G.T.; Najafi, A.; Cunier, M.; Hess, T.H.; Binkert, C.A. Angiographic Detection of Utero-Ovarian Anastomosis and Influence on Ovarian Function After Uterine Artery Embolization. Cardiovasc. Interv. Radiol. 2020, 43, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Shamy, T.; Amer, S.A.K.; Mohamed, A.A.; James, C.; Jayaprakasan, K. The Impact of Uterine Artery Embolization on Ovarian Reserve: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2020, 99, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunereau, L.; Herbreteau, D.; Gallas, S.; Cottier, J.P.; Lebrun, J.L.; Tranquart, F.; Fauchier, F.; Body, G.; Rouleau, P. Uterine Artery Embolization in the Primary Treatment of Uterine Leiomyomas: Technical Features and Prospective Follow-up with Clinical and Sonographic Examinations in 58 Patients. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2000, 175, 1267–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Li, J.; Tang, J.; Zhang, L.; Wang, D.; Sun, Z. Role of Collateral Embolization in Addition to Uterine Artery Embolization Followed by Hysteroscopic Curettage for the Management of Cesarean Scar Pregnancy. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019, 19, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitamura, Y.; Ascher, S.M.; Cooper, C.; Allison, S.J.; Jha, R.C.; Flick, P.A.; Spies, J.B. Imaging Manifestations of Complications Associated with Uterine Artery Embolization. RadioGraphics 2005, 25, S119–S132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vo, N.-J.; Andrews, R.T. Uterine Artery Embolization: A Safe and Effective, Minimally Invasive, Uterine-Sparing Treatment Option for Symptomatic Fibroids. Semin. Interv. Radiol. 2008, 25, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doucet, J.; Kiri, L.; O’Connell, K.; Kehoe, S.; Lewandowski, R.J.; Liu, D.M.; Abraham, R.J.; Boyd, D. Advances in Degradable Embolic Microspheres: A State of the Art Review. J. Funct. Biomater. 2018, 9, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, P.; Garcia-Reyes, K.; Cronan, J.; Newsome, J.; Bercu, Z.; Majdalany, B.S.; Resnick, N.; Gichoya, J.; Kokabi, N. Managing Postembolization Syndrome–Related Pain after Uterine Fibroid Embolization. Semin. Interv. Radiol. 2021, 38, 382–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feature | Pumping (Slurry) | Hand-Cut (Pledgets) | Torpedoes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preparation Time | Rapid | Time-consuming | Time-consuming (if custom-made) |

| Particle Size | Variable (often <0.5 mm) | Uniform (0.5–1–2 mm cubes) | Uniform (delivery catheter caliber) |

| Risk of Distal Embolization | High | Low | Low |

| Fertility Risk (UAE Context) | Higher (synechia, necrosis) | Lower | Lower |

| Reproducibility | Low | Moderate | High |

| Advantages | Produces smaller particles for distal vessel penetration. Easier and quicker preparation. | Larger particle size ensures proximal vessel occlusion. Reduced risk of non-target embolization. | Uniform shape allows controlled embolization. Reduced catheter clogging risk. |

| Disadvantages | Less control over particle size distribution. Higher risk of non-target embolization. Shorter occlusion duration. | Labor-intensive and time-consuming. Inconsistent particle sizes. Potential for catheter clogging. | Requires specific tools for shaping. Less effective for distal embolization. |

| Use Case | Emergency, rapid control Caution in elective fertility-sensitive cases, such as UAE. | Elective Best for controlled embolization in fertility-preserving procedures. | Routine embolotherapy (no data on UAE) Good balance of control and ease |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Minici, R.; Tiralongo, F.; Venturini, M.; Fontana, F.; Piacentino, F.; Nicoletta, M.; Coppola, A.; Guzzardi, G.; Giurazza, F.; Corvino, F.; et al. Transcatheter Arterial Embolization (TAE) of Uterine Artery with Gelatin Sponge for Cesarean Scar Pregnancy: A Current State of the Art Review. Gels 2026, 12, 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010044

Minici R, Tiralongo F, Venturini M, Fontana F, Piacentino F, Nicoletta M, Coppola A, Guzzardi G, Giurazza F, Corvino F, et al. Transcatheter Arterial Embolization (TAE) of Uterine Artery with Gelatin Sponge for Cesarean Scar Pregnancy: A Current State of the Art Review. Gels. 2026; 12(1):44. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010044

Chicago/Turabian StyleMinici, Roberto, Francesco Tiralongo, Massimo Venturini, Federico Fontana, Filippo Piacentino, Melania Nicoletta, Andrea Coppola, Giuseppe Guzzardi, Francesco Giurazza, Fabio Corvino, and et al. 2026. "Transcatheter Arterial Embolization (TAE) of Uterine Artery with Gelatin Sponge for Cesarean Scar Pregnancy: A Current State of the Art Review" Gels 12, no. 1: 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010044

APA StyleMinici, R., Tiralongo, F., Venturini, M., Fontana, F., Piacentino, F., Nicoletta, M., Coppola, A., Guzzardi, G., Giurazza, F., Corvino, F., & Laganà, D. (2026). Transcatheter Arterial Embolization (TAE) of Uterine Artery with Gelatin Sponge for Cesarean Scar Pregnancy: A Current State of the Art Review. Gels, 12(1), 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010044