Poly(N-vinyl formaldehyde)—Laponite XLG Nanocomposite Hydrogels: Synthesis and Characterization

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

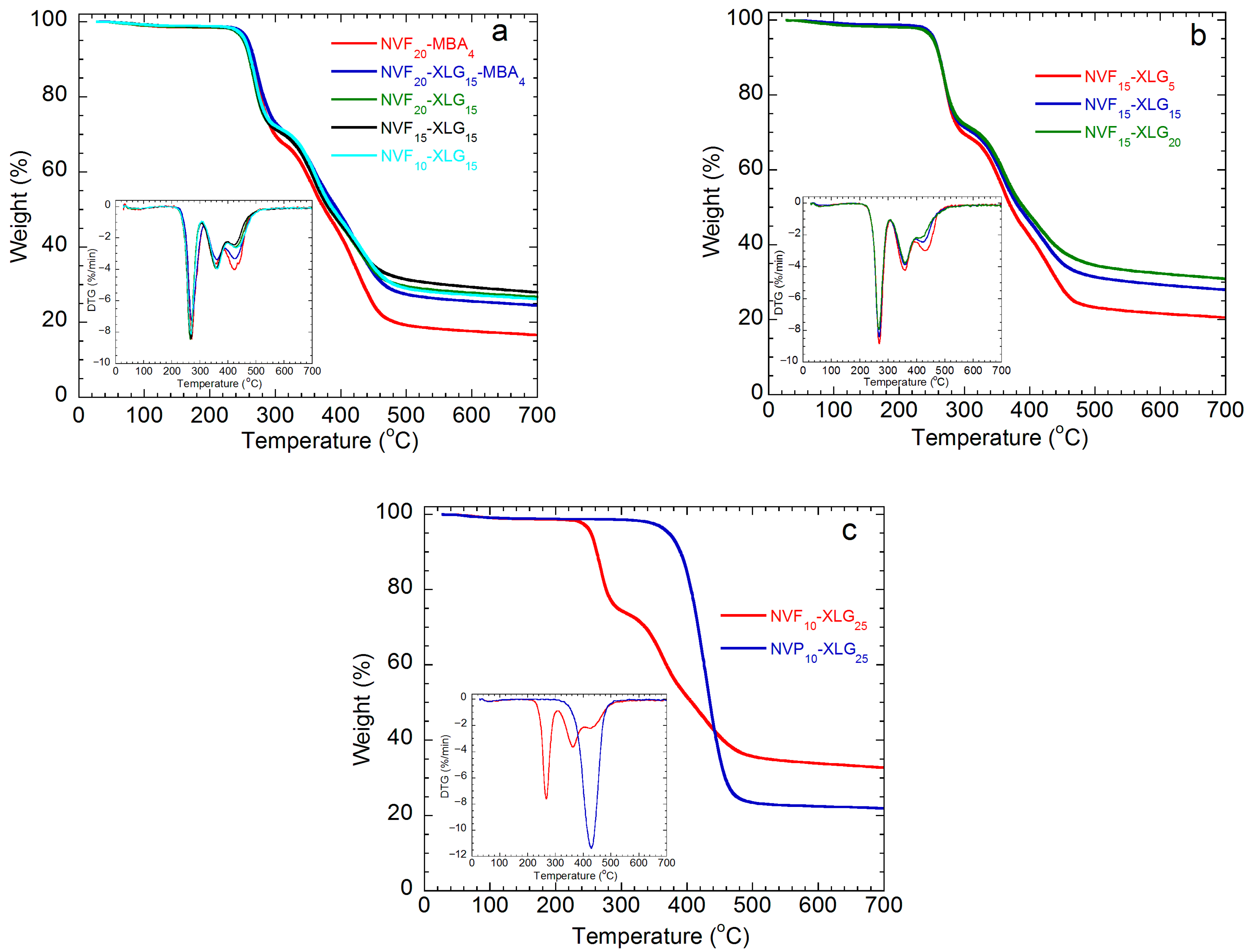

2.1. Synthesis and Structure of Hydrogels

2.2. Swelling Degree Investigations

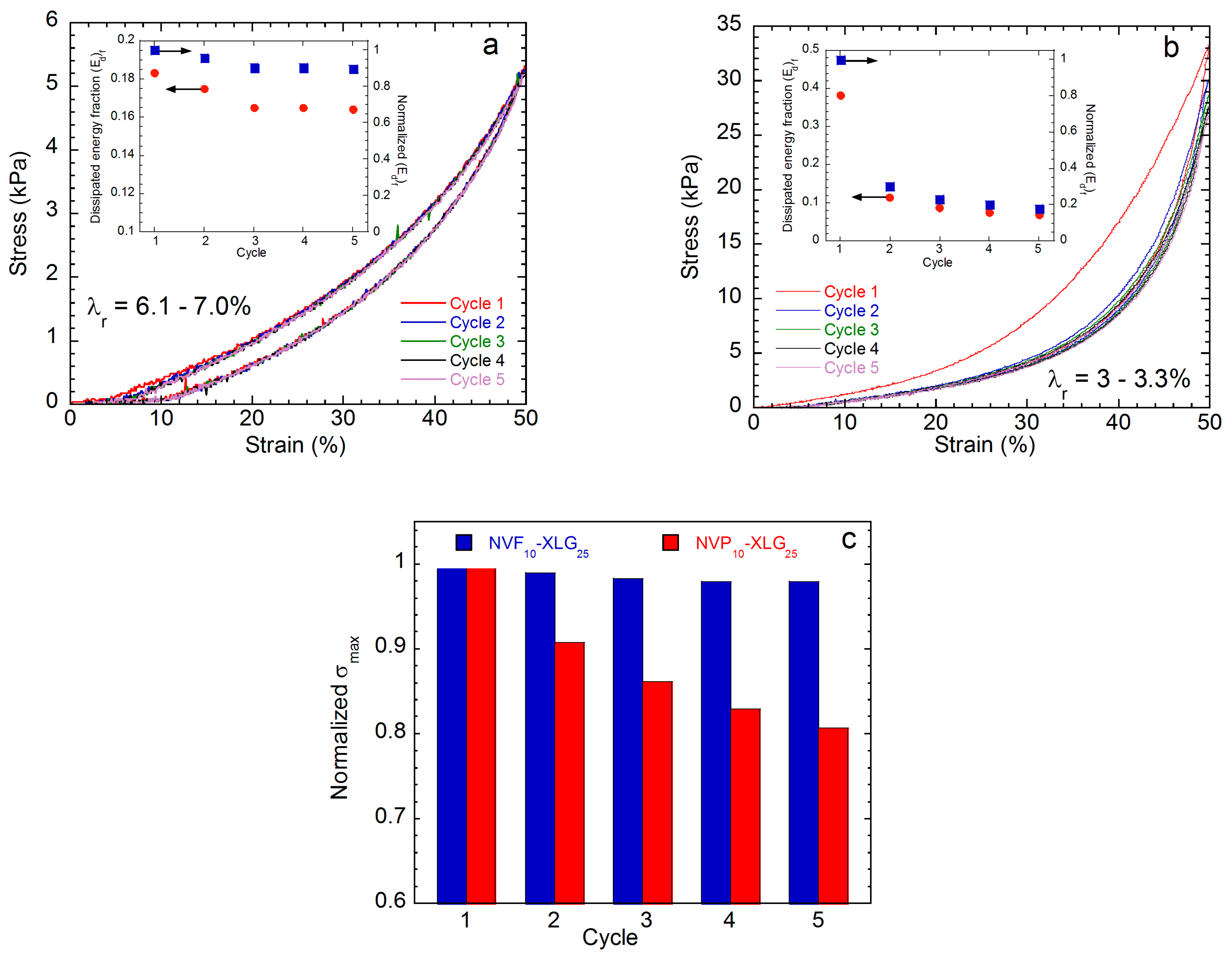

2.3. Mechanical Properties of Hydrogels

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Hydrogel Preparation

4.3. Swelling Degree Determinations

4.4. Characterizations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Marhefka, J.N.; Marascalco, P.J.; Chapman, T.M.; Russell, A.J.; Kameneva, M.V. Poly(N-vinylformamide)—A drag-reducing polymer for biomedical applications. Biomacromolecules 2006, 7, 1597–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panarin, E.F.; Nesterova, N.A.; Gavrilova, I.I.; Ivanova, N.P.; Belokhvostova, A.T.; Potapenkova, L.S. Synthesis and immunomodulating properties of poly(N-vinylformamide). Pharm. Chem. J. 2010, 44, 7–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Adlam, D.J.; Wang, R.; Altujjar, A.; Jia, Z.; Saunders, J.M.; Hoyland, J.A.; Rai, N.; Saunders, B.R. Injectable colloidal hydrogels of N-vinylformamide microgels dispersed in covalently interlinked pH-responsive methacrylic acid-based microgels. Biomacromolecules 2023, 24, 2173–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinschmidt, R.K., Jr.; Renz, W.L.; Carroll, W.E.; Yacoub, K.; Drescher, J.; Nordquist, A.F.; Chen, N. N-vinylformamide—Building block for novel polymer structures. J. Macromol. Sci. Part A Pure Appl. Chem. 1997, 34, 1885–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinschmidt, R.K., Jr. Polyvinylamine at last. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2010, 48, 2257–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Chapman, T.M.; Beckman, E.J. Poly(ethylene glycol)-block-poly(N-vinylformamide) copolymers synthesized by the RAFT methodology. Macromolecules 2003, 36, 2563–2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Yamago, S. Synthesis of poly(N-vinylamide)s and poly(vinylamine)s and their block copolymers by organotellurium-mediated radical polymerization. Angew. Chem. 2019, 58, 7113–7116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurowska, I.; Dupre-Demorsy, A.; Balayssac, S.; Hennetier, M.; Ric, A.; Bourdon, V.; Ando, T.; Ajiro, H.; Coutelier, O.; Destarac, M. Taylor-made poly(vinylamine) via purple-LED activated RAFT polymerization of N-vinylformamide. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2022, 44, 2200729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suekama, T.C.; Aziz, V.; Mohammadi, Z.; Berkland, C.; Gehrke, S.H. Synthesis and characterization of poly(N-vinyl formamide) hydrogels—A potential alternative to polyacrylamide hydrogels. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2012, 51, 435–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swider, J.; Tata, A.; Sokolowska, K.; Witek, E.; Proniewicz, E. Studies on N-vinylformamide cross-linked copolymers. J. Mol. Struct. 2015, 1102, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yooyod, M.; Ross, S.; Phewchan, P.; Daengmankhong, J.; Pinthong, T.; Tuancharoensri, N.; Mahasaranon, S.; Viyoch, J.; Ross, G.M. Homo-and copolymer hydrogels based on N-vinylformamide: An investigation of the impact of water structure on controlled release. Gels 2023, 9, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Xu, W.; Pich, A. Temperature and pH-dual-responsive poly(vinyl lactam) copolymers functionalized with amine side groups via RAFT polymerization. Polym. Chem. 2016, 7, 5011–5022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zhang, H.; Wang, X.; Yang, X.; Lin, R.; Zhang, F.; Liu, Y.; Xu, K.; Zhou, C.; Wang, P. H2S-responsive zwitterionic hydrogel as a self-healing agent for plugging microcracks in oil-well cement. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2023, 127, 523–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buwalda, S.J.; Boere, K.W.M.; Dijkstra, P.J.; Feijen, J.; Vermonden, T.; Hennink, W.E. Hydrogels in a hystorical perspective: From simple networks to smart materials. J. Control Release 2014, 190, 254–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, F.; Othman, M.B.H.; Javed, F.; Ahmad, Z.; Akil, H.M. Classification, processing and application of hydrogels: A review. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2015, 57, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Chen, X.; Yuk, H.; Lin, S.; Liu, X.; Parada, G. Soft materials by design: Unconventional polymer networks give extreme properties. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 4309–4372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wichterle, O.; Lim, D. Hydrophilic gels for biological use. Nature 1960, 185, 117–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Kowalczuk, M.; Heaselgrave, W.; Britland, S.T.; Martin, C.; Radecka, I. The production and application of hydrogels for wound management: A review. Eur. Polym. J. 2019, 111, 134–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, J.T.; Wechsler, M.E.; Peppas, N.A. Advanced biomedical hydrogels: Molecular architecture and its impact on medical applications. Regen. Biomater. 2021, 8, rbab060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavi, S.E.; Panah, N.; Page, F.; Gholami, M.; Dastfal, A.; Sharma, L.A.; Shahmabadi, H.E. Hydrogel-based therapeutic coatings for dental implants. Eur. Polym. J. 2022, 181, 111652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbagh, F.; Kim, B.S. Microneedles for transdermal drug delivery using clay-based composites. Exp. Opin. Drug Deliv. 2022, 19, 1099–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ye, Q.; Yu, S.; Akhavan, B. Poly ethylene glycol (PEG)-based hydrogels for drug delivery and cancer therapy: A comprehensive review. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2023, 12, 2300105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Shu, H.; Zhang, L.; Huang, S. Latest advances in hydrogel therapy for ocular diseases. Polymer 2024, 306, 127207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wei, W.; Guo, Z.; Liu, X.; Liu, J.; Bing, T.; Yu, Y.; Yang, X.; Cai, Q. Organic-inorganic composite hydrogels: Compositions, properties, and applications in regenerative medicine. Biomater. Sci. 2024, 12, 1079–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitura, S.; Sionkowska, A.; Jaiswal, A. Biopolymers for hydrogels in cosmetics: Review. J. Mat. Sci. Mater. Med. 2020, 31, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashari, A.; Shirvan, A.R.; Shakeri, M. Cellulose-based hydrogels for personal care products. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2018, 29, 2853–2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Lv, X.; Xie, T.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xu, X. Tailored hydrogel entrapped catalyst with highly active, controlled catalytic activity for the removal of 4-nitrophenol (4-NP). Eur. Polym. J. 2023, 200, 112533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Guo, Y.; Zhao, F.; Yu, G. Hydrogels as emerging material platform for solar water purification. Acc. Chem. Res. 2019, 52, 3244–3253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Liu, J.; Lin, S.; Zhao, X. Hydrogel machines. Mat. Today 2020, 36, 102–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadian, M.; Jaymand, M. Interpenetrating polymer network hydrogels for removal of synthetic dyes: A comprehensive review. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2023, 486, 215152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandu, T.; Chiriac, A.L.; Zaharia, A.; Iordache, T.V.; Sarbu, A. New trends in preparation and use of hydrogels for water treatment. Gels 2025, 11, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, C.; Wang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Qi, Y.; Wu, N.; Zhang, S.; Xu, W. Recent advances of hydrogel in agriculture: Synthesis, mechanism, properties and applications. Eur. Polym. J. 2024, 219, 113376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goy, C.B.; Chaile, R.E.; Madrid, R.E. Microfluidics and hydrogel: A powerful combination. React. Func. Polym. 2019, 145, 104314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Guan, Q.; Li, M.; Saiz, E.; Hou, X. Nature-inspired strategies for the synthesis of hydrogel actuators and their applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2023, 140, 101665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin Sadeque, M.S.; Chowdhury, H.K.; Rafique, M.; Durmus, M.A.; Ahmed, M.K.; Hasan, M.M.; Erbas, A.; Sarpkaya, I.; Inci, F.; Ordu, M. Hydrogel-integrated optical fiber sensors and their applications: A comprehensive review. J. Mat. Chem. C 2023, 11, 9383–9424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, K.; Wan, Y.; Wei, J.; Chen, T. Hydrogel-based sensors for human-machine interaction. Langmuir 2023, 39, 16975–16985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, T.; Chaturvedi, P.; Llamas-Garro, I.; Velazquez-Gonzalez, J.S.; Dubey, R.; Mishra, S.K. Smart materials for flexible electronics and devices: Hydrogel. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 12984–13004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Sun, Z.; Zhu, Q.; Cao, X.; Feng, Y.; Yin, H. In situ generated hydrogels exhibiting simultaneous high-temperature and high-salinity resistance for deep hydrocarbon reservoir exploitation. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2024, 63, 18263–18278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdi, M.K.; Vatanpour, V.; Taghizadeh, A.; Taghizadeh, M.; Ganjali, M.R.; Munir, M.T.; Habibzadeh, S.; Saeb, M.R.; Ghaedi, M. Hydrogel membranes: A review. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2020, 114, 111023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakai, T. Gelation mechanism and mechanical properties of Tetra-PEG gels. React. Func. Polym. 2013, 73, 898–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, T. Experimental verification of homogeneity in polymer gels. Polym. J. 2014, 46, 517–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.P.; Katsuyama, Y.; Kurokawa, T.; Osada, Y. Double-network hydrogels with extremely high mechanical strength. Adv. Mater. 2003, 15, 1155–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Chen, S.; Jiang, W.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, N.; Wang, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhang, D. Double-network hydrogels for biomaterials: Structure-property relationships and drug delivery. Eur. Polym. J. 2023, 185, 111807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumura, Y.; Ito, K. The polyrotaxane gel: A topological gel by figure-of-eight crosslinks. Adv. Mater. 2001, 13, 485–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malkoch, M.; Vestberg, R.; Gupta, N.; Mespouille, L.; Dubois, P.; Mason, A.F.; Hedrick, J.L.; Liao, Q.; Frank, C.W.; Kingsbury, K.; et al. Synthesis of well-defined hydrogel networks using Click chemistry. Chem. Commun. 2006, 26, 2774–2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraguchi, K. Nanocomposite hydrogels. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2007, 11, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraguchi, K.; Takehisa, T. Nanocomposite hydrogels: A unique organic-inorganic network structure with extraordinary mechanical, optical, and swelling/de-swelling properties. Adv. Mater. 2002, 14, 1120–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, S.; Endo, H.; Karino, T.; Haraguchi, K.; Shibayama, M. Gelation mechanism of poly(N-isopropylacrylamide)-clay nanocomposite gels. Macromolecules 2007, 40, 4287–4295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Liu, Y.; Sun, B.; Zhang, W.; Liu, X.; Yu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Kuckling, D.; Adler, H.J.P. A novel highly resilient nanocomposite hydrogel with low histeresis and ultrahigh elongation. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2006, 27, 1023–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okay, O.; Oppermann, W. Polyacrylamide-clay nanocomposite hydrogels: Rheological and light scattering characterization. Macromolecules 2007, 40, 3378–3387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, L.; Hu, X.; Liu, X.; Tong, Z. Network chain density and relaxation of in situ synthesized polyacrylamide/hectorite clay nanocomposite hydrogels with ultrahigh tensibility. Polymer 2008, 49, 5064–5071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraguchi, K.; Farnworth, R.; Ohbayashi, A.; Takehisa, T. Compositional effects on mechanical properties of nanocomposite hydrogels composed of poly(N,N-dimethylacrylamide) and clay. Macromolecules 2003, 36, 5732–5741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ma, J.; Yang, S.; Xu, J. PDMAA/Clay nanocomposite hydrogels based on two different initiations. Colloid Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2011, 390, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wu, R.; Zhu, J.; Guo, P.; Ren, W.; Xu, S.; Wang, J. pH/temperature double responsive behaviors and mechanical strength of laponite-crosslinked poly(DEA-co-DMAEMA) nanocomposite hydrogels. J. Polym. Sci. B Polym. Phys. 2015, 53, 876–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X.; Ma, Y.; Hou, C.; Gao, F.; Zhang, Y.; Ruan, C.; Pan, H.; Lu, W.W.; Liu, W. 3D-Printed high strength bioactive supramolecular polymer/clay nanocomposite hydrogel scaffold for bone regeneration. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 3, 1109–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X.; Ruan, C.; Shen, J.; Zheng, C.; Zhao, X.; Pan, H.; Lu, W.W. Clay-based nanocomposite hydrogel with attractive mechanical properties and sustained bioactive ion release for bone defect repair. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2021, 9, 2394–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xu, W.; Xiong, Y.; Peng, C.; Liu, W.; Zeng, G.; Peng, Y. Synthesis and characterization of pH and temperature double-sensitive nanocomposite hydrogels consisting of poly(dimethylaminoethyl methacrylate) and clay. J. Mater. Res. 2013, 28, 1394–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, M.; Wu, W.; Liu, F.; Theato, P.; Zhu, M. Swelling behavior of thermosensitive nanocomposite hydrogels composed of oligo(ethylene glycol) methacrylates and clay. Eur. Polym. J. 2015, 69, 472–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.J.; Li, W.D.; Rong, J.H. Preparation and characterization of PVP/clay nanocomposite hydrogels. Chem. J. Chin. Univ. 2010, 31, 2081–2087. [Google Scholar]

- Podaru, I.A.; Stanescu, P.O.; Ginghina, R.; Stoleriu, S.; Trica, B.; Somoghi, R.; Teodorescu, M. Poly(N-vinylpyrrolidone)–Laponite XLG nanocomposite hydrogels: Characterization, properties and comparison with divinyl monomer-crosslinked hydrogels. Polymers 2022, 14, 4216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomas, H.; Alves, C.S.; Rodrigues, J. Laponite®: A key nanoplatform for biomedical applications? Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2018, 14, 2407–2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiaee, G.; Dimitrakakis, N.; Sharifzadeh, S.; Kim, H.J.; Avery, R.K.; Moghaddam, K.M.; Haghniaz, R.; Yalcintas, E.P.; de Barros, N.R.; Karamikamkar, S.; et al. Laponite-based nanomaterials for drug delivery. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2022, 11, 2102054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stealey, S.T.; Gaharwar, A.K.; Zustiak, S.P. Laponite-based nanocomposite hydrogels for drug delivery applications. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mongondry, P.; Tassin, J.F.; Nicolai, T. Revised state diagram of Laponite dispersions. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2005, 283, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haraguchi, K. Synthesis and properties of soft nanocomposite materials with novel organic/inorganic network structures. Polym. J. 2011, 43, 223–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, T.; Hellweg, T.; Spange, S.; Hesse, S.; Jäger, C.; Bellmann, C. Synthesis and properties of crosslinked polyvinylformamide and polyvinylamine hydrogels in conjunction with silica particles. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2002, 40, 3144–3152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, K.; Serizawa, T.; Akashi, M. Synthesis and thermosensitive properties of poly[(N-vinylamide)-co-(vinyl acetate)]s and their hydrogels. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2003, 204, 1027–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Khondee, S.; Linz, T.H.; Berkland, C. Poly(N-vinylformamide) nanogels capable of pH-sensitive protein release. Macromolecules 2008, 41, 6546–6554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajiro, H.; Kan, K.; Akashi, M. Thermal treatment of poly(N-vinylformamide) produced hydrogels without the use of chemical crosslinkers. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2017, 17, 837–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, L.A.; Gul, K.; Ali, I.; Khan, A.; Muhammad, S.; Ullah, M.; Bibi, I.; Sultana, S. Poly(N-vinylformamide-co-acrylamide) hydrogels: Synthesis, composition and rheology. Iran. Polym. J. 2022, 31, 845–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shang, D.; Niu, Z. Removal of heavy metals by poly(vinyl pyrrolidone)/Laponite nanocomposite hydrogels. Adv. Mater. Res. 2013, 631, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, L.; Zhu, S.; Hrymak, A.N.; Pelton, R.H. The nature of crosslinking in N-vinylformamide free-radical polymerization. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2001, 22, 212–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedden, R.C.; Saxena, H.; Cohen, C. Mechanical properties and swelling behavior of end-linked poly(diethylsiloxane) networks. Macromolecules 2000, 33, 8676–8684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathmann, E.E.L.; McCormick, C.L. Water-soluble copolymers. 48. Reactivity ratios of N-vinylformamide with acrylamide, sodium acrylate, and n-butyl acrylate. Macromolecules 1993, 26, 5249–5252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninciuleanu, C.; Ianchis, R.; Alexandrescu, E.; Mihaescu, C.; Trica, B.; Scomoroscenco, C.; Nistor, C.; Petcu, C.; Preda, S.; Teodorescu, M. Nanocomposite hydrogels based on poly(methacrylic acid) and Laponite XLG. UPB. Sci. Bull. Ser. B 2021, 83, 43–58. [Google Scholar]

- Demirci, S.; Sutekin, S.D.; Kurt, S.B.; Guven, O.; Sahiner, N. Poly(vinyl amine) microparticles derived from N-vinylformamide and their versatile use. Polym. Bull. 2022, 79, 7729–7751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rattanawongwiboon, T.; Khongbunya, N.; Namvijit, K.; Lertsarawut, P.; Laksee, S.; Hemvichian, K.; Madrid, J.F.; Ummartyotin, S. Eco-friendly dye adsorbent from poly(vinylamine) grafted onto bacterial cellulose sheet by using gamma radiation-induced simultaneous grafting and base hydrolysis. J. Polym. Environ. 2024, 32, 3048–3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anggarini, N.H.; Suhartini, M.; Rahmawati, R.; ega Putri, M.A.; Yunus, M.Y.; Deswita, D.; Sugiharto, U. Synthesis and application of bioadsorbent for Y(III) ions from poly(vinylamine) grafted onto rayon by radiation-induced grafting. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2025, 57, 103398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lis, M.; Chudzik, K.; Bakierska, M.; Swietoslawski, M.; Gajewska, M.; Rutkowska, M.; Molenda, M. Aqueous binder for nanostructured carbon anode materials for Li-ion batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2019, 166, A5354–A5361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molenda, M.; Dziembaj, R.; Drozdek, M.; Podstawka, E.; Proniewicz, L.M. Direct preparation of conductive carbon layer (CCL) on alumina as a model system for direct preparation of carbon coated particles of the composite Li-ion electrodes. Solid State Ionics 2008, 179, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witek, E.; Pazdro, M.; Bortel, E. Mechanism for base hydrolysis of poly(N-vinylformamide). J. Macromol. Sci. Part A Pure Appl. Chem. 2007, 44, 503–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninciuleanu, C.M.; Ianchis, R.; Alexandrescu, E.; Mihaescu, C.I.; Burlacu, S.; Trica, B.; Nistor, C.L.; Preda, S.; Scomoroscenco, C.; Gifu, C.; et al. Adjusting some properties of poly(methacrylic acid) (nano)composite hydrogels by means of silicon-containing inorganic fillers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninciuleanu, C.M.; Ianchis, R.; Alexandrescu, E.; Mihaescu, C.I.; Scomoroscenco, C.; Nistor, C.L.; Preda, S.; Petcu, C.; Teodorescu, M. The effects of monomer, crosslinking agent, and filler concentrations on the viscoelastic and swelling properties of poly(methacrylic acid) hydrogels: A comparison. Materials 2021, 14, 2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, B.; Venuti, V.; D’Amico, F.; Gessini, A.; Castiglione, F.; Mele, A.; Punta, C.; Melone, L.; Crupi, V.; Majolino, D.; et al. Water and polymer dynamics in a model polysaccharide hydrogel: The role of hydrophobic/hydrophilic balance. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 963–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richbourg, N.R.; Rausch, M.K.; Peppas, N.A. Cross-evaluation of stiffness measurement methods for hydrogels. Polymer 2022, 258, 125316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cursaru, B.; Stanescu, P.O.; Teodorescu, M. Compression properties of hydrogels synthesized from diepoxy-terminated poly(ethylene glycol)s and aliphatic polyamines. Mater. Plast 2008, 45, 314–319. [Google Scholar]

- Huglin, M.B.; Rehab, M.M.A.M.; Zakaria, M.B. Thermodynamic interactions in copolymeric hydrogels. Macromolecules 1986, 19, 2986–2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Li, J.; Runge, M.B.; Dadsetan, M.; Chen, Q.; Lu, L.; Yaszemski, M.J. Cross-linking characteristics and mechanical properties of an injectable biomaterial composed of polypropylene fumarate and polycaprolactone co-polymer. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2011, 22, 489–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norioka, C.; Inamoto, Y.; Hajime, C.; Kawamura, A.; Miyata, T. A universal method to easily design tough and stretchable hydrogels. NPG Asia Mater. 2021, 13, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kureha, T.; Takahashi, K.; Kino, M.; Kida, H.; Hirayama, T. Controlling the mechanical properties of hydrogels via modulating the side-chain length. Soft Matter 2023, 19, 2878–2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bui, H.L.; Huang, C.J. Tough polyelectrolyte hydrogels with antimicrobial property via incorporation of natural multivalent phytic acid. Polymers 2019, 11, 1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sample | SD a g Hydrogel/g Xerogel | Ecomp b kPa | G c kPa | Ecomp/G | τc,max d kPa | (1 − λ)max e % | Tc f kJ/m3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NVP10-XLG25 | 22.3 ± 0.5 | 13.9 ± 0.2 | 4.20 ± 0.08 | 3.30 | 72.2 ± 11.5 | 62.9 ± 2.3 | 11.0 ± 1.5 |

| NVF10-XLG25 | 34.0 ± 1.2 | 4.3 ± 0.1 | 1.32 ± 0.04 | 3.29 | 197.9 ± 42.1 | 90 | 15.4 ± 2.4 |

| NVF10-XLG15 | 57.9 ± 3.6 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 0.36 ± 0.03 | 3.30 | 675.6 ± 34.5 | 90 | 20.5 ± 1.4 |

| NVF15-XLG15 | 33.1 ± 0.2 | 5.6 ± 0.1 | 1.70 ± 0.03 | 3.29 | 3765.7 ± 1822.1 | 90 | 97.7 ± 34.9 |

| NVF20-XLG15 | 24.1 ± 0.2 | 13.8 ± 0.3 | 4.20 ± 0.10 | 3.29 | 4552.1 ± 1547.6 | 90 | 153.1 ± 42.5 |

| NVF15-XLG20 | 24.6 ± 1.1 | 13.4 ± 1.0 | 4.07 ± 0.29 | 3.30 | 2189.37 ± 780.5 | 90 | 93.2 ± 22.2 |

| NVF20-XLG15-MBA4 | 7.6 ± 0.3 | 338.2 ± 9.5 | 102.6 ± 2.9 | 3.30 | 3366.4 ± 527.6 | 72.9 ± 4.2 | 620.4 ± 129.3 |

| NVF20-MBA4 | 15.1 ± 0.1 | 70.9 ± 1.1 | 21.50 ± 0.34 | 3.30 | 790.8 ± 64.5 | 77.0 ± 0.9 | 116.1 ± 8.4 |

| NVF20-MBA2 | 28.2 ± 0.1 | 14.4 ± 0.3 | 4.37 ± 0.08 | 3.30 | 690.2 ± 113.6 | 78.5 ± 1.8 | 69.5 ± 10.1 |

| NVF20-MBA1 | 40.0 ± 0.1 | 5.7 ± 0.1 | 1.73 ± 0.04 | 3.29 | 163.1 ± 20.7 | 77.3 ± 0.5 | 11.2 ± 1.2 |

| Sample | SD a g Hydrogel/g Xerogel | Etens b kPa | τt,max c kPa | (λ − 1)max d % | Tt e kJ/m3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NVP10-XLG25 | 21.8 ± 0.1 | 12.3 ± 4.0 | 10.0 ± 1.1 | 80.8 ± 11.3 | 3.9 ± 0.8 |

| NVF10-XLG25 | 35.1 ± 0.9 | 5.0 ± 2.5 | 23.3 ± 3.0 | 610.1 ± 69.4 | 74.2 ± 14.8 |

| NVF10-XLG15 | 58.9 ± 1.0 | 2.3 ± 0.8 | 4.0 ± 0.3 | 299.2 ± 21.8 | 6.1 ± 0.9 |

| NVF15-XLG15 | 37.8 ± 0.9 | 4.8 ± 1.6 | 23.4 ± 3.6 | 630.0 ± 75.2 | 70.6 ± 18.8 |

| NVF20-XLG15 | 28.7 ± 0.5 | 9.0 ± 2.5 | 39.8 ± 16.1 | 560.1 ± 169.3 | 114.0 ± 67.8 |

| NVF15-XLG20 | 26.7 ± 0.3 | 10.3 ± 1.0 | 56.4 ± 9.0 | 843.7 ± 207.7 | 252.9 ± 124.3 |

| NVF20-XLG15-MBA4 | 8.0 ± 0.1 | 288.5 ± 9.2 | 440.1 ± 42.9 | 85.5 ± 9.6 | 179.7 ± 36.9 |

| NVF20-MBA4 | 13.9 ± 0.1 | 62.4 ± 5.1 | 63.8 ± 9.0 | 113.7 ± 30.7 | 44.0 ± 17.9 |

| NVF20-MBA2 | 27.6 ± 0.1 | 13.0 ± 2.0 | 31.6 ± 4.4 | 94.8 ± 8.5 | 10.8 ± 2.5 |

| Entry | Monomer | Crosslinking a Agent | Network Homogeneity b | Compression | Tensile | Ref. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ecomp c kPa | τc,max d kPa | (1 − λ)max e % | Etens f kPa | τt,max g kPa | (λ − 1)max h % | |||||

| 1 | NVF | NVEE | homogeneous | 3.4–90.7 | 303–1139 | 70–98 | NR | NR | NR | [9] |

| 2 | NVF | heat | heterogeneous | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | [69] |

| 3 | NVF | BVU | homogeneous | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | [66] |

| 4 | NVF | PEGDA | heterogeneous | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | [11] |

| 5 | NVF | BDEP | homogeneous nanogels | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | [68] |

| 6 | NVF | NVEE | homogeneous microgels | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | [3] |

| 7 | DMAEMA | XLS | homogeneous | NR | NR | NR | 0.4–1.9 | 52–282 | 243–659 | [57] |

| 8 | NIPAM | XLG | homogeneous | NR | NR | NR | 1.5–9.9 | 41–109 | 857–1424 | [47] |

| 9 | AAm | XLS | homogeneous | NR | NR | NR | 3.8–19.1 | 107–319 | 1672–2829 | [49] |

| 10 | DMAA | XLG | homogeneous | NR | NR | NR | 1.2–15.5 | 34.5–255.6 | 1264–1654 | [52] |

| 11 | NVF | XLG | homogeneous | 1.2–13.8 | 198–4552 | ≥90 | 2.3–10.3 | 4.0–56.4 | 299–843 | present work |

| Hydrogel Sample 2 | NVF 3 (g) | NVP 4 (g) | XLG 5 (g) | MBA 6 (g) | AIBN 7 (g) | DW (g) | GF (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NVF10-XLG25 | 1.0 | - | 0.250 | - | 0.006 | 8.75 | 91 |

| NVP10-XLG25 | - | 1.0 | 0.250 | - | 0.006 | 8.75 | 87.5 |

| NVF10-XLG15 | 1.0 | - | 0.150 | - | 0.006 | 8.85 | 85 |

| NVF15-XLG15 | 1.5 | - | 0.225 | - | 0.009 | 8.20 | 91 |

| NVF20-XLG15 | 2.0 | - | 0.300 | - | 0.012 | 7.70 | 93.5 |

| NVF15-XLG5 | 1.5 | - | 0.075 | - | 0.009 | 8.40 | 71.5 |

| NVF15-XLG20 | 1.5 | - | 0.300 | - | 0.009 | 8.20 | 91.5 |

| NVF20-XLG15-MBA4 | 2.0 | - | 0.300 | 0.173 | 0.012 | 7.55 | 94 |

| NVF20-MBA4 | 2.0 | - | - | 0.173 | 0.012 | 7.85 | 81.5 |

| NVF20-MBA2 | 2.0 | - | - | 0.087 | 0.012 | 7.90 | 80 |

| NVF20-MBA1 | 2.0 | - | - | 0.044 | 0.012 | 7.85 | 80 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Stănescu, P.O.; Serafim, A.; Chiriac, A.-L.; Zaharia, A.; Şomoghi, R.; Teodorescu, M. Poly(N-vinyl formaldehyde)—Laponite XLG Nanocomposite Hydrogels: Synthesis and Characterization. Gels 2026, 12, 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010031

Stănescu PO, Serafim A, Chiriac A-L, Zaharia A, Şomoghi R, Teodorescu M. Poly(N-vinyl formaldehyde)—Laponite XLG Nanocomposite Hydrogels: Synthesis and Characterization. Gels. 2026; 12(1):31. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010031

Chicago/Turabian StyleStănescu, Paul Octavian, Andrada Serafim, Anita-Laura Chiriac, Anamaria Zaharia, Raluca Şomoghi, and Mircea Teodorescu. 2026. "Poly(N-vinyl formaldehyde)—Laponite XLG Nanocomposite Hydrogels: Synthesis and Characterization" Gels 12, no. 1: 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010031

APA StyleStănescu, P. O., Serafim, A., Chiriac, A.-L., Zaharia, A., Şomoghi, R., & Teodorescu, M. (2026). Poly(N-vinyl formaldehyde)—Laponite XLG Nanocomposite Hydrogels: Synthesis and Characterization. Gels, 12(1), 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010031