Development of Antimicrobial Comb-like Hydrogel Based on PEG and HEMA by Gamma Radiation for Biomedical Use

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

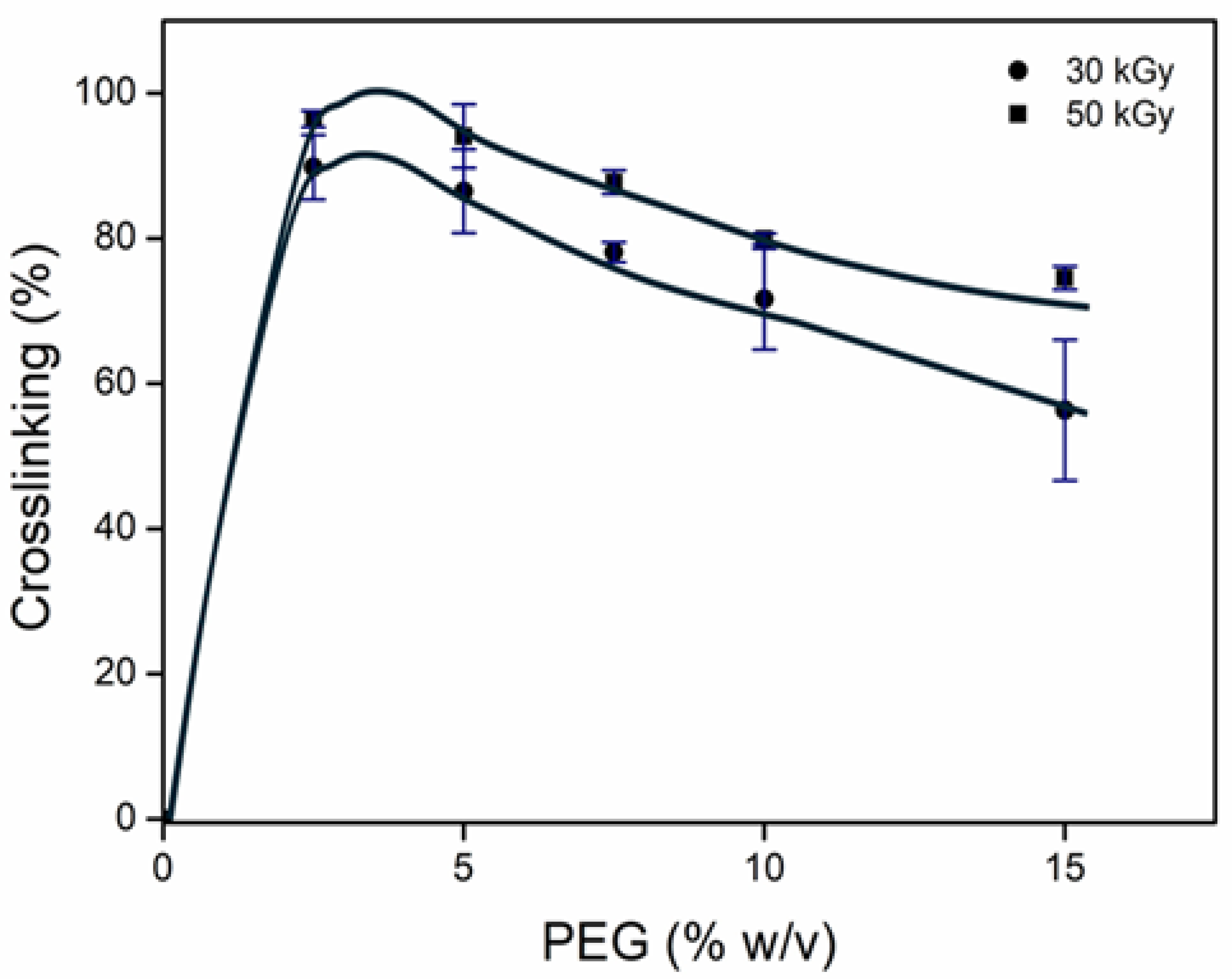

2.1. Obtention of net-PEG

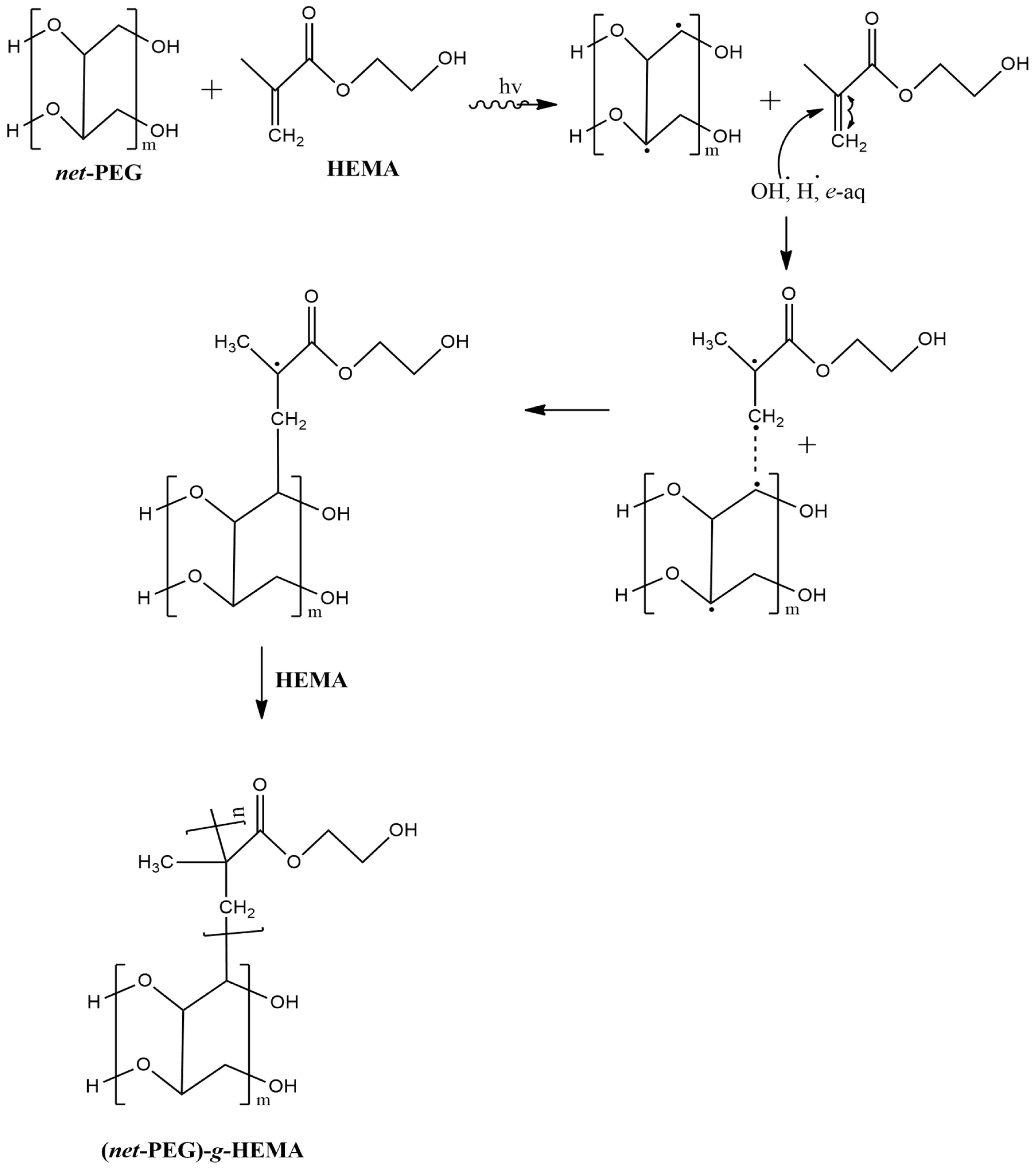

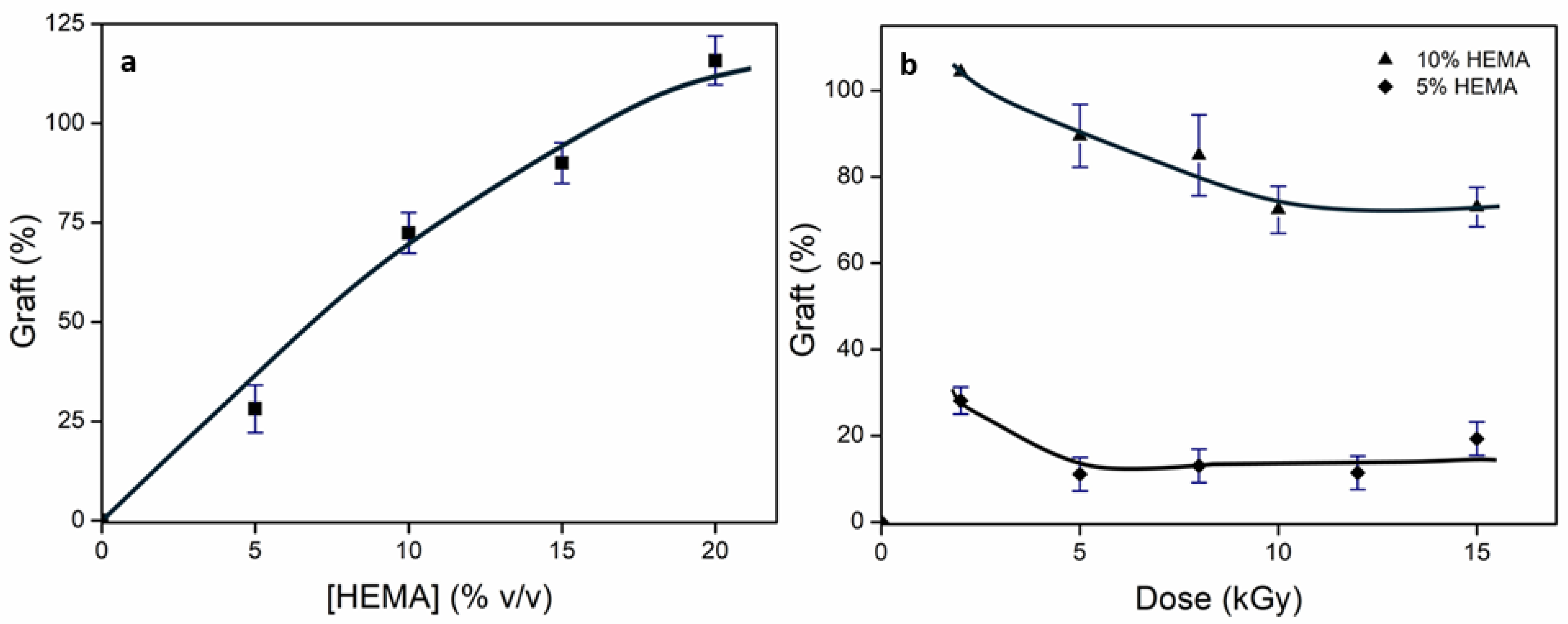

2.2. Obtention of Comb-like Hydrogel: (net-PEG)-g-HEMA

2.3. Characterization

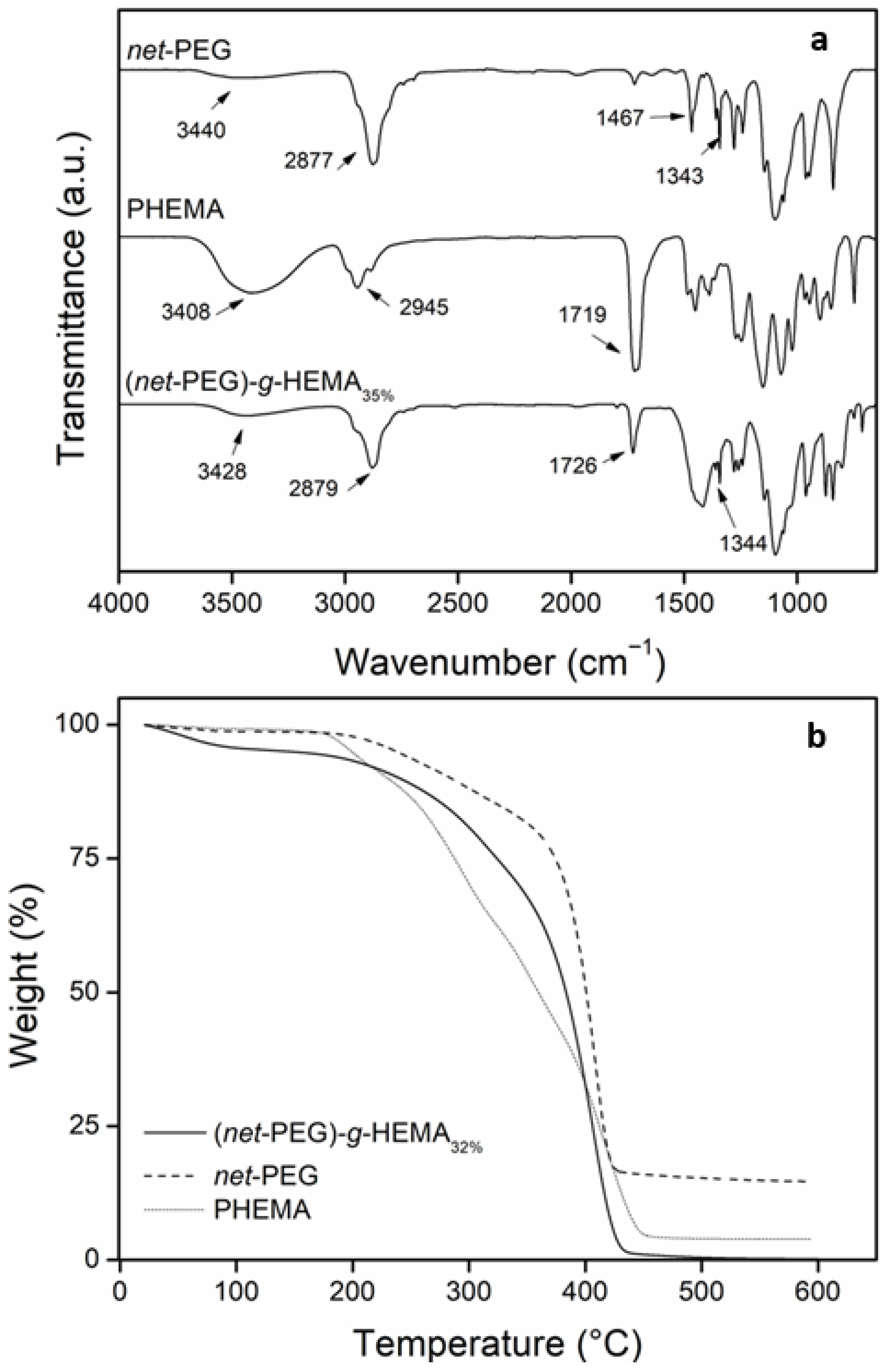

2.3.1. FTIR and TGA

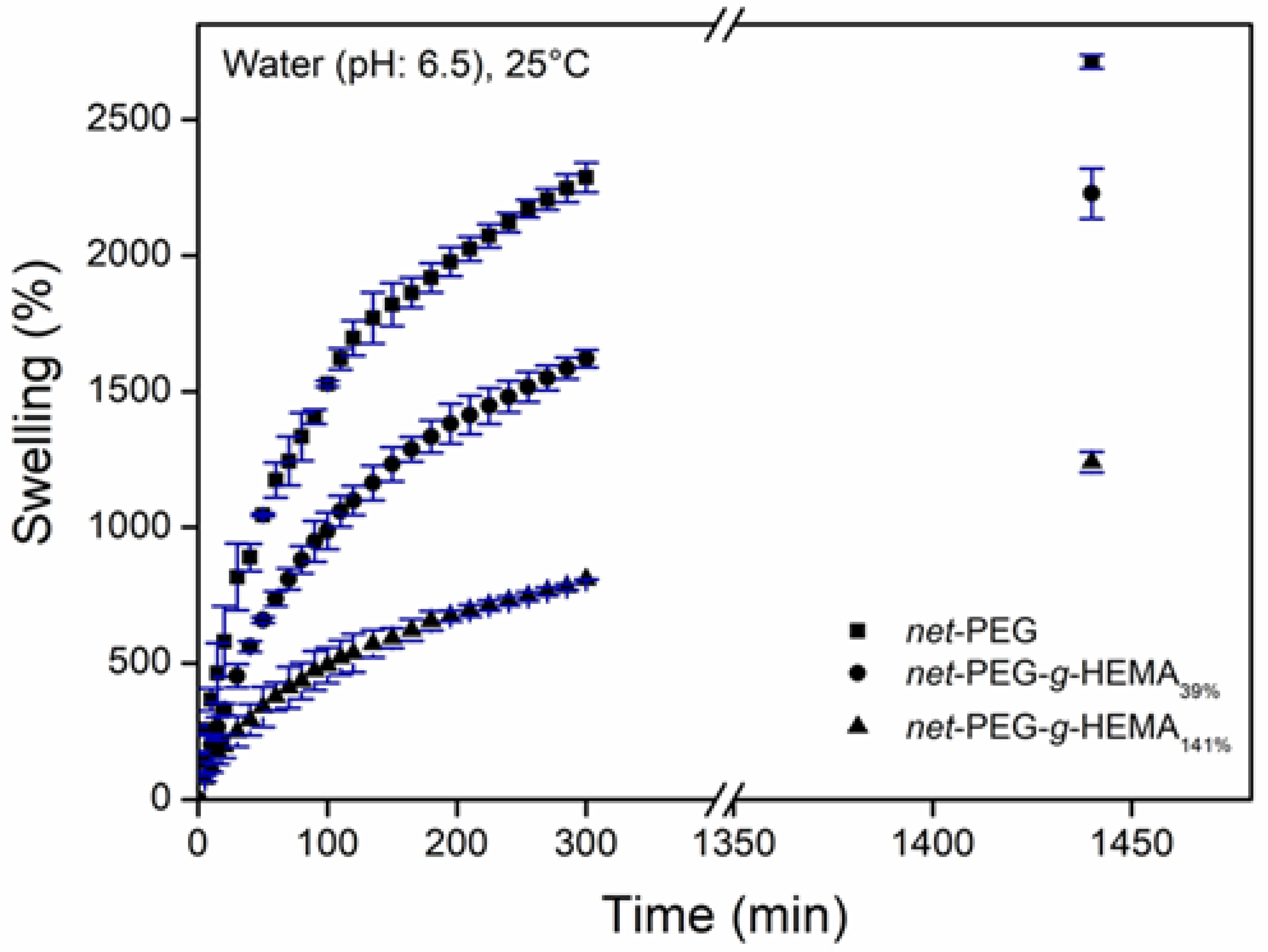

2.3.2. Swelling Behavior

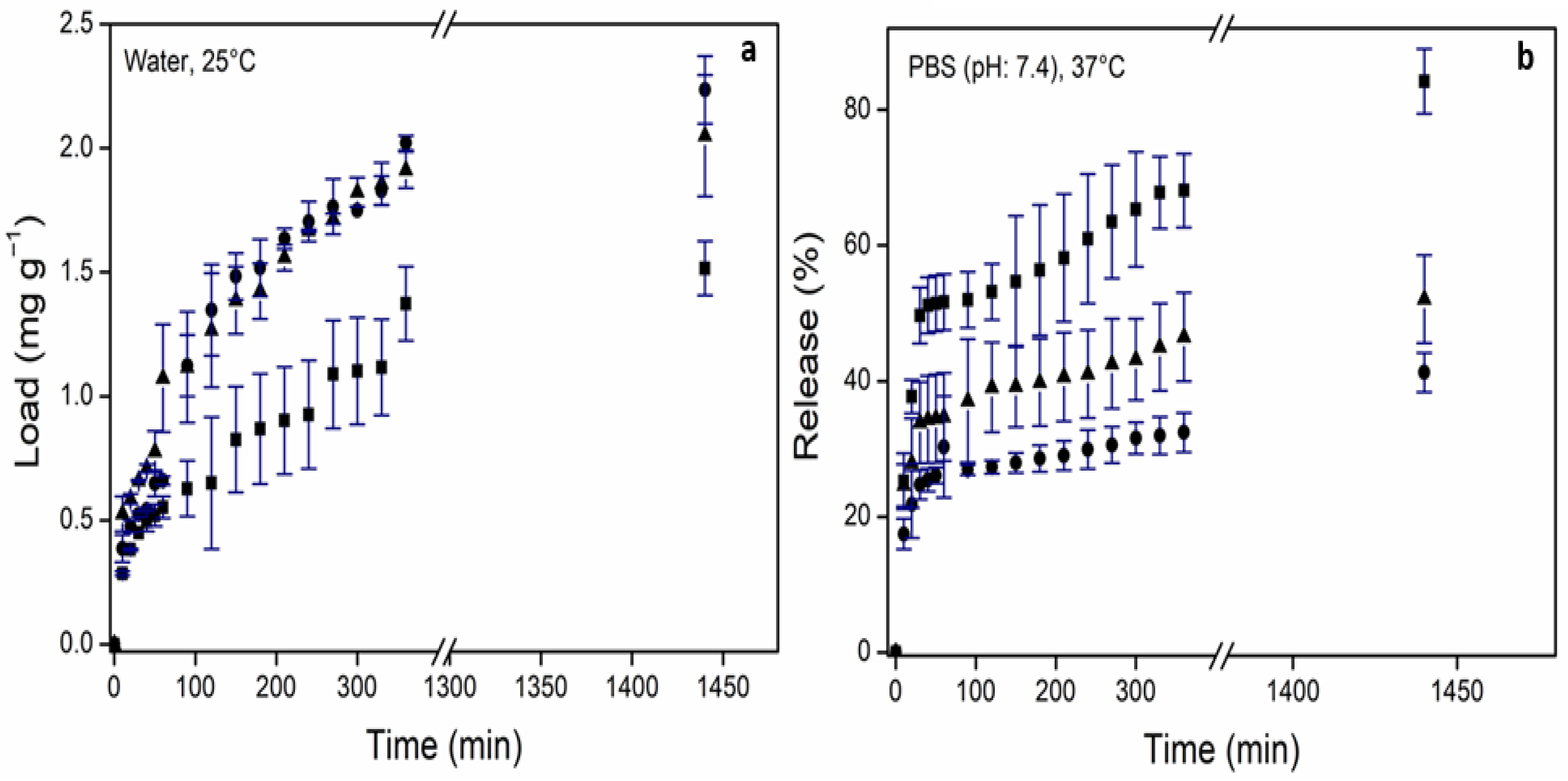

2.3.3. In Vitro Drug Loading and Release Studies

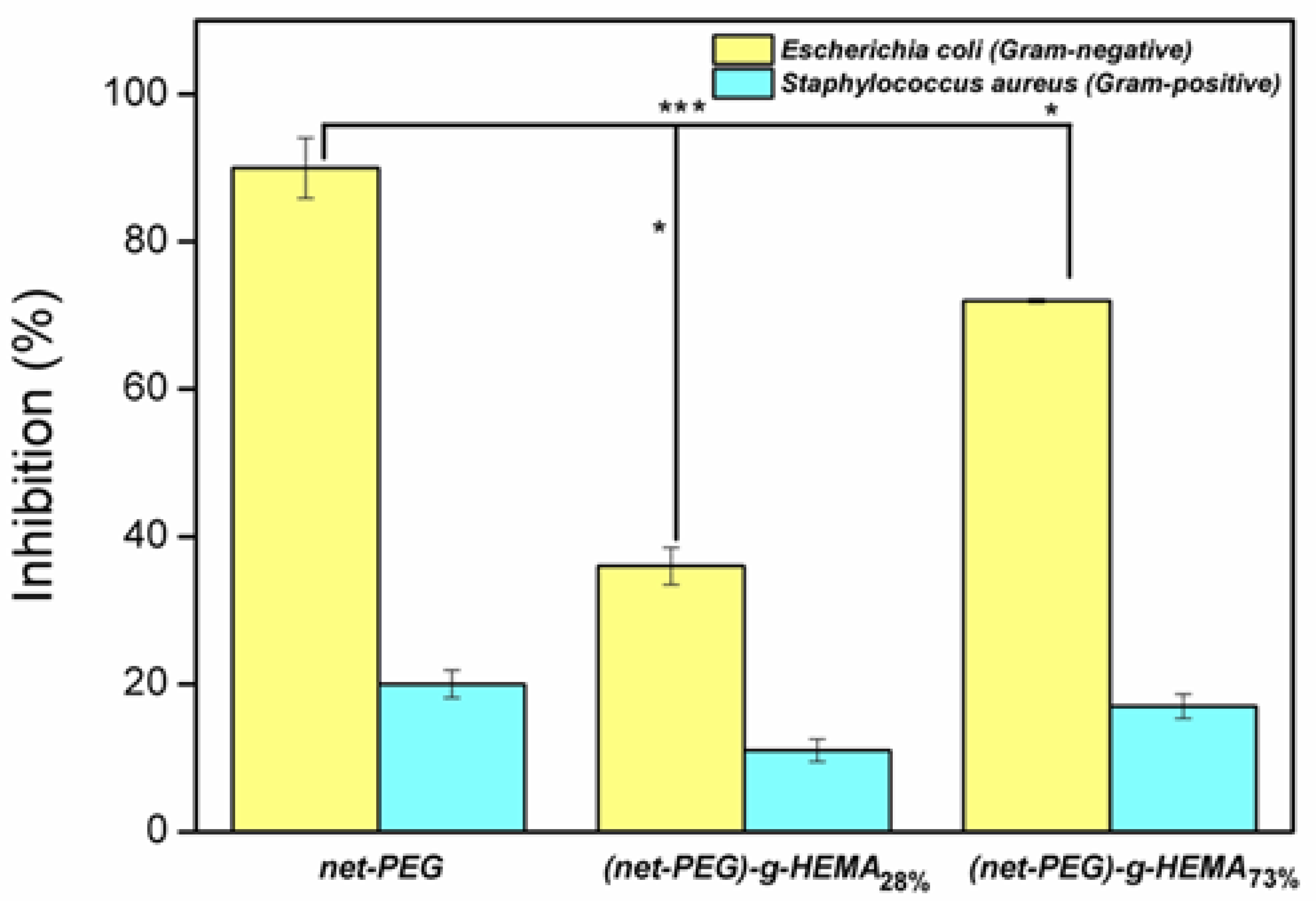

2.3.4. Antimicrobial Activity

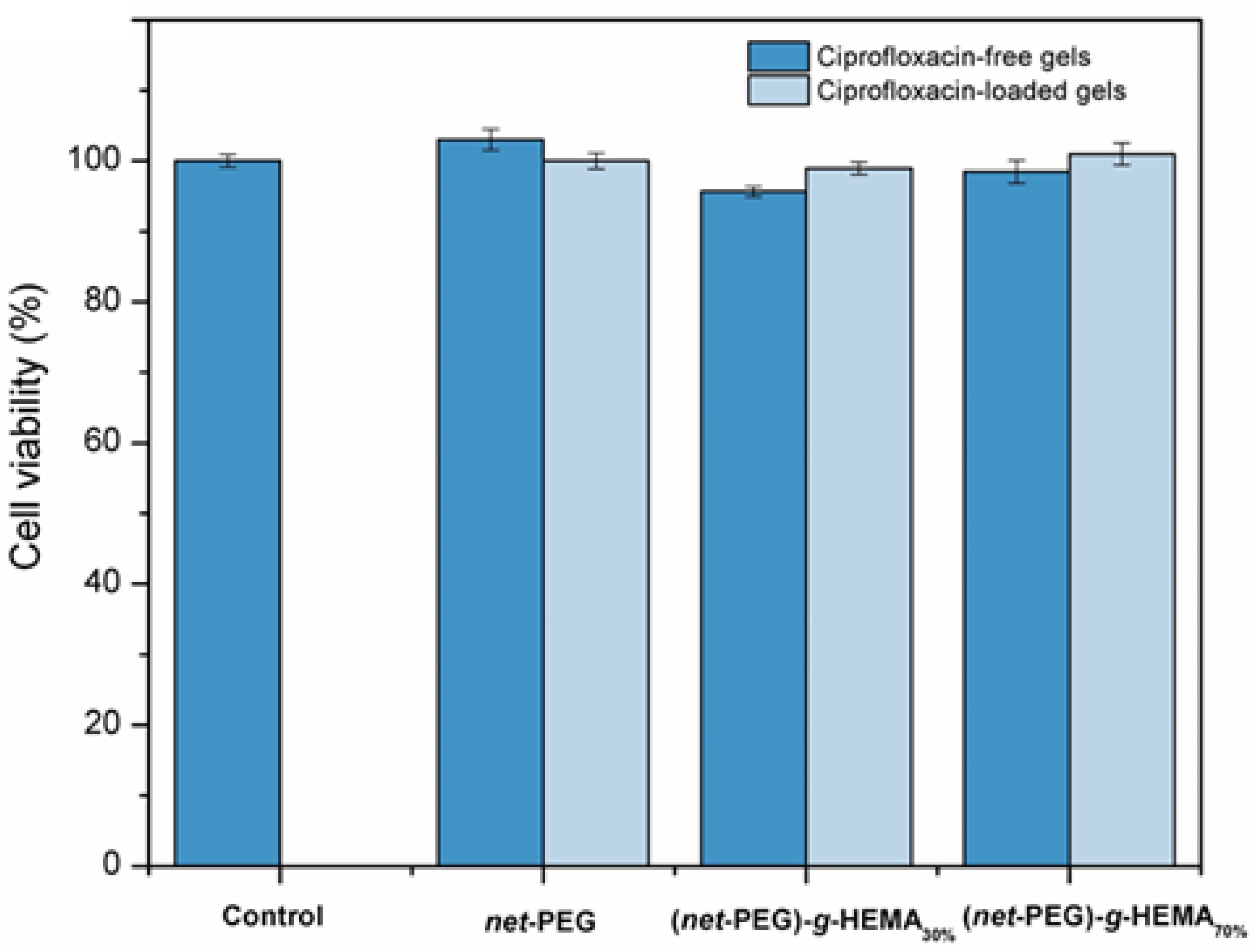

2.3.5. Evaluation of Biocompatibility

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Crosslinking of Poly(ethylene glycol)

4.2. Synthesis of Comb-like Hydrogel

4.3. Characterization Techniques

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Peppas, N.A.; Hoffman, A.S. 1.3.2E Hydrogels. In Biomaterial Science: An Introduction to Materials in Medicine, 4th ed.; Wagner, W.R., Sakiyama-Elbert, S.E., Zhang, G., Yaszemski, M.J., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, H.; Gogoi, B.; Sharma, I.; Das, D.K.; Azad, M.H.; Pramanik, D.D.; Pramanik, A. Hydrogels as potential biomaterial for multimodal therapeutic applications. Mol. Pharm. 2024, 21, 4827–4848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, H.; Duan, L.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, J.; Zhang, K. Current hydrogel advances in physicochemical and biological response-driven biomedical application diversity. Signal Transduc. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, Z.; Salman, S.; Khan, S.A.; Amin, A.; Rahman, Z.U.; Al-Ghamdi, Y.O.; Akhtar, K.; Bakhsh, E.M.; Khan, S.B. Versatility of Hydrogels: From Synthetic Strategies, Classification, and Properties to Biomedical Applications. Gels 2022, 8, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, K.H.; Lee, J.W. Synthesis and characterization of poly(ethylene Glycol) based thermoresponsive Hydrogels for Cell Sheet Engineering. Materials 2016, 9, 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.; Manolache, S.; Wong, A.C.L.; Denes, F.S. Antibiofouling ability of polyethylene glycol of different molecular weights grafted onto polyester surfaces by cold plasma. Polym. Bull. 2011, 66, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Ren, T.; Zhu, J.; Mao, Z.; Gao, C. Adsorption of plasma proteins and fibronectin on poly(hydroxylethyl methacrylate) brushes of different thickness and their relationship with adhesion and migration of vascular smooth muscle cells. Regen. Biomater. 2014, 1, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peppas, N.A.; Keys, K.B.; Torre-Lugo, M.; Lowman, A.M. Poly(ethylene glycol)-containing hydrogels in drug delivery. J. Control. Release 1999, 62, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobiç, S.N.; Filipovic, J.M.; Tomic, S.J. Synthesis and characterization of poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate/itaconic acid/poly(ethylene glycol) dimethacrylate) hydrogels. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 179, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, Y.K.; Jung, Y.P.; Kim, J.H.; Chung, D.J. Preparation and Properties of PEG-Modified PHEMA Hydrogel and the Morphological Effect. Macromol. Res. 2006, 14, 394–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajpai, A.K.; Shrivastava, M. Enhanced water sorption of a semi-interpenetrating polymer network (IPN) of poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate) (PHEMA) and poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG). J. Macromol. Sci. Part A 2012, 39, 667–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.Y.; Zhang, J.; Fang, Q.C.; Jiang, D.M.; Lin, C.C.; Zeng, Y.; Jiang, J.S. Salt and pH sensitive semi-interpenetrating polyelectrolyte hydrogels poly(HEMA-co-METAC)/PEG and its BSA adsorption behavior. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2014, 132, 41537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, K.S.V.K.; Subha, M.C.S.; Sairam, M.; Halligudi, S.B.; Aminabhavi, T.M. Synthesis, characterization and controlled release characteristics of PEGylated hydrogels for diclofenac sodium. Des. Monomers Polym. 2006, 9, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisheh, H.R.; Sabzevari, A.; Ansari, M.; Kabiri, K. Development of HEMA-Succinic Acid-PEG Bio-Based Monomers for High-Performance Hydrogels in Regenerative Medicine. Biopolymers 2024, 116, e23631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, P.M.; Edwin, L. Nano copper oxide incorporated polyethylene glycol hydrogel: An efficient antifouling coating for cage fishing net. Int. Biodeter. Biodegrad. 2016, 115, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayramoglu, G.; Can Akcal, K.; Gultekin, S.; Bengu, E.; Arica, M.Y. Preparation and characterization of poly(hydroxyethyl methacrylate-co-poly(ethyleneglycol-methacrylate)/hydroxypropyl-chitosan) hydrogel films: Adhesion of rat mesenchymal stem cells. Macromol. Res. 2011, 19, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisheh, H.R.; Sabzevari, A.; Ansari, M.; Kabiri, K.; Eslami, H.; Kohestanian, M. Synthesis of New macromer Based on HEMA-TA-PEG for Preparation of Bio-Based Hydrogels for Regenerative Medicine Applications. J. Polym. Environ. 2025, 33, 3076–3091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Tang, Z.; Tang, X.G.; Liang, Z.; Feng, J.; Ye, L.; Tan, Y.; Jiang, Y.P.; Lan, M.; Zhu, D.; et al. Wireless wearable systems based on multifunctional conductive PEG-HEMA hydrogel with anti-freeze, anti-UV, self-healing, and self-adhesive performance for health monitoring. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2024, 695, 134196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, G.; Chen, R.; Ning, C.; Zhang, L.; Ruan, X.; Liao, J. Effects of argon plasma treatment on surface characteristic of photopolymerization PEGDA–HEMA hydrogels. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2012, 124, 459–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naikwadi, A.T.; Sharma, B.K.; Bhatt, K.D.; Mahanwar, P.A. Gamma Radiation Processed Polymeric Materials for High Performance Applications: A Review. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 837111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashfaq, A.; Clochard, M.C.; Coqueret, X.; Dispenza, C.; Driscoll, M.S.; Ulanski, P.; Al-Sheikhly, M. Polymerization Reactions and Modifications of Polymers by Ionizing Radiation. Polymers 2020, 12, 2877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Islam, M.; Hasan, K.; Nam, K.W. A comprehensive review of radiation-induced hydrogels: Synthesis, properties and multidimensional applications. Gels 2024, 10, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazo, L.M.; Burillo, G. Novel comb type hydrogels of net-[PP-g-(PAAc)]-g-4VP Synthesized by gamma radiation and their immobilization of Cu (II). Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2010, 79, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, P.; Schott, B.J.; Means, A.K.; Grunlan, M.A. Comb Architecture to Control the Selective Diffusivity of a Double Network Hydrogel. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2020, 2, 5269–5277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.Q.; Li, J.M.; Pan, T.T.; Li, P.Y.; He, W.D. Comb-Type Grafted Hydrogels of PNIPAM and PDMAEMA with Reversed Network-Graft Architectures from Controlled Radical Polymerizations. Polymers 2016, 8, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Lee, S.B.; Kim, S.J.; Lee, Y.M. Rapid temperature/pH response of porous alginate-g-poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) hydrogels. Polymer 2002, 43, 7549–7558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Gómez, A.; Pérez-Calixto, M.; Velazco-Medel, M.A.; Burillo, G. Synthesis of the IPN poly(ethylene glycol)/poly(N-isopropyl acrylamide) by ionizing radiation and its antifouling properties. MRS Commun. 2022, 12, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinks, J.W.T.; Woods, R.J. An Introduction to Radiation Chemistry, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Son Inc.: London, UK, 1976; pp. 237–241. ISBN 978-0471816701. [Google Scholar]

- Islas, L.; Burillo, G.; Ortega, A. Graft Copolymerization of 2-Hydroxyethyl methacrylate onto chitosan using radiation technique for release of diclofenac. Macromol. Res. 2018, 26, 690–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dafader, N.C.; Rahman, N.; Alam, M.F. Study on grafting of acrylic acid onto cotton using gamma radiation and its application as dye adsorbent. Nucl. Sci. Appl. 2014, 23, 37–40. [Google Scholar]

- Tinoco, D.; Ortega, A.; Islas, L.; García-Uriostegui, L.; Burillo, G. Different hydrogel architectures synthesized by gamma radiation based on chitosan and dimethylacrylamide. MRS Commun. 2018, 8, 617–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaman, S.; Karaipekli, A.; Sarı, A.; Biçer, A. Polyethylene glycol (PEG)/diatomite composite as a novel form-stable phase change material for thermal energy storage. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2011, 95, 1647–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voorhees, K.J.; Baugh, S.F.; Stevenson, D.N. An investigation of the thermal degradation of poly(ethylene glycol). J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 1994, 30, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, A.K.; Mohanty, S.; Nayak, S.K. Effect of PEG on PLA/PEG blend and its nanocomposites: A study of thermo-mechanical and morphological characterization. Polym. Compos. 2013, 35, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirelli, K.; Coşkun, M.; Kaya, E.A. detailed study of thermal degradation of poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate). Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2001, 72, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jora, M.Z.; Cardoso, M.V.C.; Sabadini, E. Dynamical aspects of water-poly(ethylene glycol) solutions studied by 1H NMR. J. Mol. Liq. 2016, 222, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yu, C.; Kumar, H.; He, X.; Lu, Q.; Bai, H.; Kim, K.; Hu, J. The Effect of Crosslinking Degree of Hydrogels on Hydrogel Adhesion. Gels 2022, 8, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackl, E.V.; Khutoryanskiy, V.V.; Tiguman, G.M.B.; Ermolina, I. Evaluation of water properties in HEA-HEMA hydrogels swollen in aqueous-PEG solutions using thermoanalytical techniques. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2015, 121, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flory, P.J. Principles of Polymer Chemistry; Cornell University Press: London, UK, 1953; pp. 576–593. ISBN 978-0801401343. [Google Scholar]

- Macke, N.; Hemmingsen, C.M.; Rowan, S.J. The effect of polymer grafting on the mechanical properties of PEG-grafted cellulose nanocrystals in poly(lactic acid). J. Polym. Sci. 2022, 60, 3318–3330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conley, Z.C.; Bodine, T.J.; Chou, A.; Zechiedrich, L. Wicked: The untold story of ciprofloxacin. PLoS Pathog. 2018, 14, e1006805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, S.; O’Brien-Simpson, N.M.; Connal, L.A. Antibiofouling polymer interfaces: Poly(ethylene glycol) and other promising candidates. Polym. Chem. 2015, 6, 198–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare, M.; Bigham, A.; Zare, M.; Luo, H.; Ghomi, E.R.; Ramakrishna, S. pHEMA: An Overview for Biomedical Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bignotti, F.; Baldi, F.; Grassi, M.; Abrami, M.; Spagnoli, G. Hydrophobically-modified PEG hydrogels with controllable hydrophilic/hydrophobic balance. Polymers 2021, 13, 1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.; Yu, L.; Ding, J. PEG-based thermosensitive and biodegradable hydrogels. Acta Biomater. 2021, 128, 42–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.X.; Li, Y.; Liu, M.F.; Zhao, R. Ciprofloxacin enhances the biofilm formation of Staphylococcus aureus via an agrC-dependent mechanism. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1328947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maurizi, L.; Forte, J.; Ammendolia, M.G.; Hanieh, P.N.; Conte, A.L.; Relucenti, M.; Donfrancesco, O.; Ricci, C.; Rinaldi, F.; Marianecci, C.; et al. Effect of Ciprofloxacin-Loaded Niosomes on Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus Biofilm Formation. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghomi, E.R.; Khalili, S.; Khorasani, S.N.; Neisiany, R.E. Wound dressings: Current advances and future directions. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2019, 136, 47738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huzum, B.; Puha, B.; Necoara, R.M.; Gheorghevici, S.; Puha, G.; Filip, A.; Sirbu, P.D.; Alexa, O. Biocompatibility assessment of biomaterials used in orthopedic devices: An overview (Review). Exp. Ther. Med. 2021, 22, 1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, G.; Hassan, A.; Shahid, M.; Irfan, A.; Chaudhry, A.R.; Farooqi, Z.H.; Begum, R. 2-Hydroxyethyl methacrylate-based polymer microgels and their hybrids. React. Funct. Polym. 2024, 200, 105919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Qi, C.; Sun, C.; Huo, F.; Jiang, X. Poly(ethylene glycol) alternatives in biomedical applications. Nano Today 2023, 48, 101738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Zero Order | First Order | Higuchi | Korsmeyer–Peppas | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ko (mg min−1) | R2 | K1 (min−1) | R2 | KH (mg min−0.5) | R2 | Kp (min−1) | n | R2 | |

| net-PEG | 0.0247 | 0.8302 | 0.0004 | 0.7671 | 1.1451 | 0.9481 | 29.2146 | 0.1379 | 0.9014 |

| (net-PEG)-g-HEMA30% | 0.0112 | 0.9033 | 0.0003 | 0.8444 | 0.4842 | 0.9195 | 15.5561 | 0.1239 | 0.9302 |

| (net-PEG)-g-HEMA66% | 0.0126 | 0.7165 | 0.0003 | 0.6585 | 0.6158 | 0.9099 | 21.7121 | 0.1208 | 0.9666 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Contreras, A.; Ortega, A.; Magaña, H.; López, J.; Burillo, G. Development of Antimicrobial Comb-like Hydrogel Based on PEG and HEMA by Gamma Radiation for Biomedical Use. Gels 2026, 12, 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010032

Contreras A, Ortega A, Magaña H, López J, Burillo G. Development of Antimicrobial Comb-like Hydrogel Based on PEG and HEMA by Gamma Radiation for Biomedical Use. Gels. 2026; 12(1):32. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010032

Chicago/Turabian StyleContreras, Alfredo, Alejandra Ortega, Héctor Magaña, Jonathan López, and Guillermina Burillo. 2026. "Development of Antimicrobial Comb-like Hydrogel Based on PEG and HEMA by Gamma Radiation for Biomedical Use" Gels 12, no. 1: 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010032

APA StyleContreras, A., Ortega, A., Magaña, H., López, J., & Burillo, G. (2026). Development of Antimicrobial Comb-like Hydrogel Based on PEG and HEMA by Gamma Radiation for Biomedical Use. Gels, 12(1), 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010032