Camellia Saponin-Enhanced Sodium Alginate Hydrogels for Sustainable Fruit Preservation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

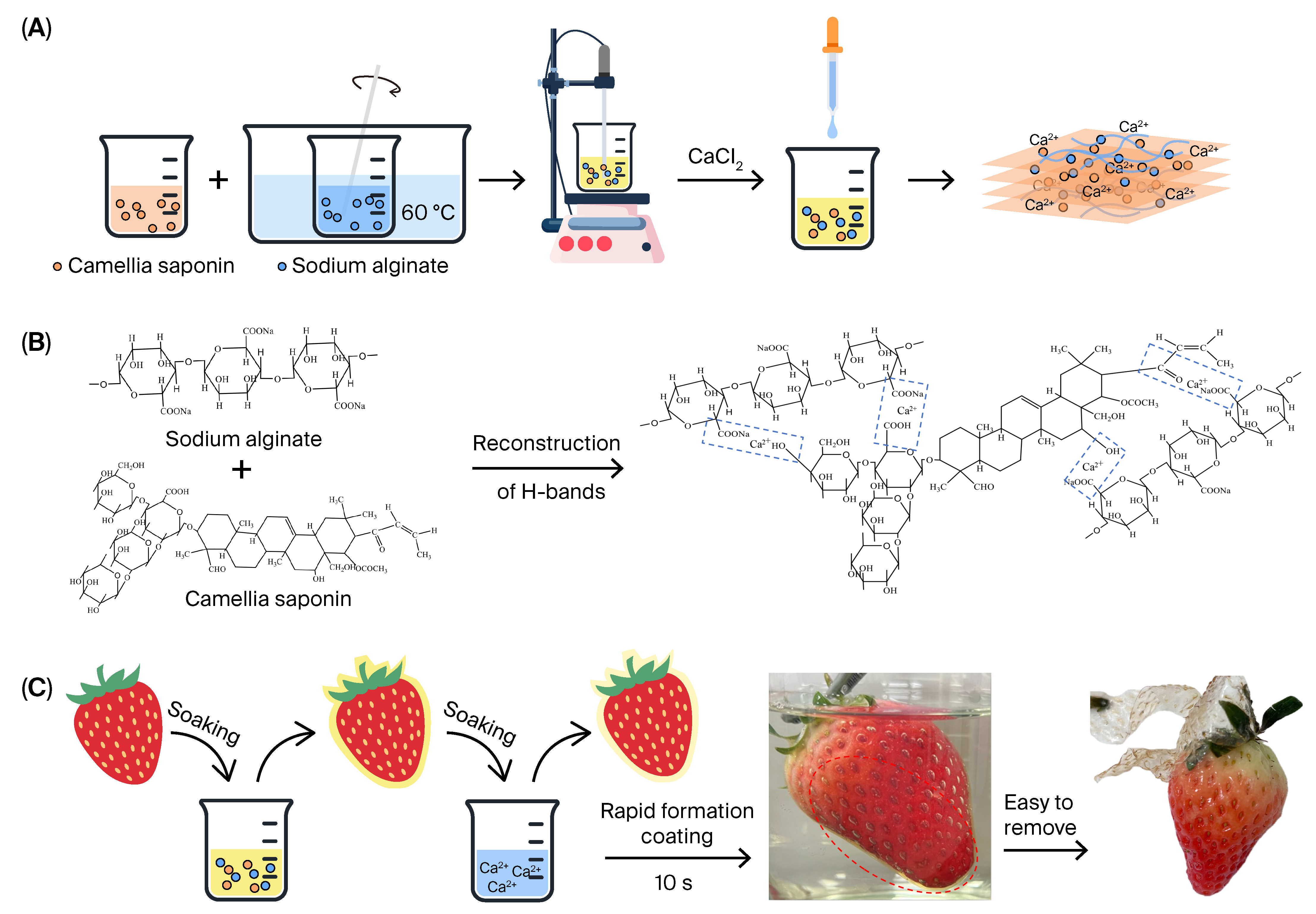

2.1. Fabrication of Composite Hydrogel Films

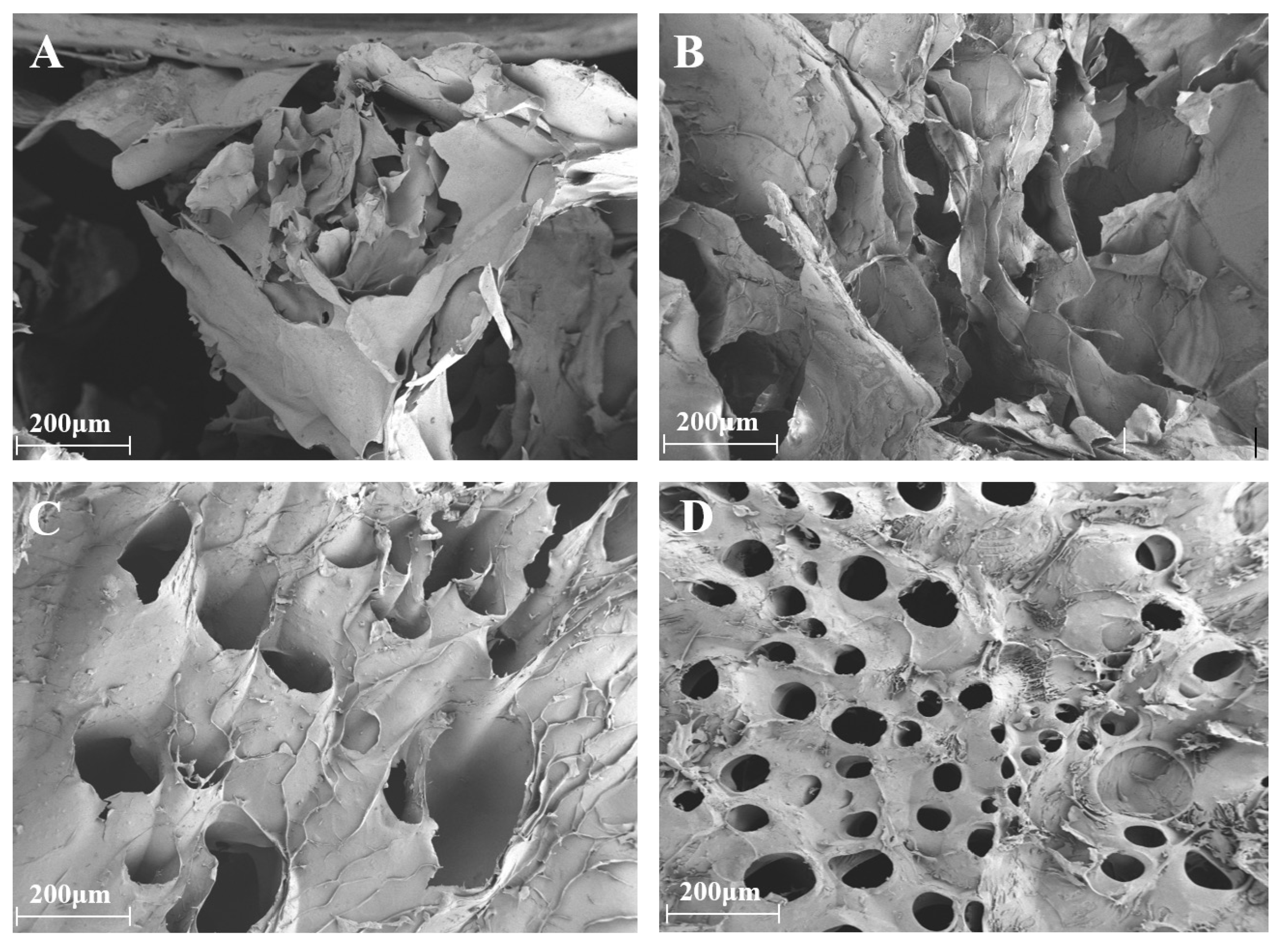

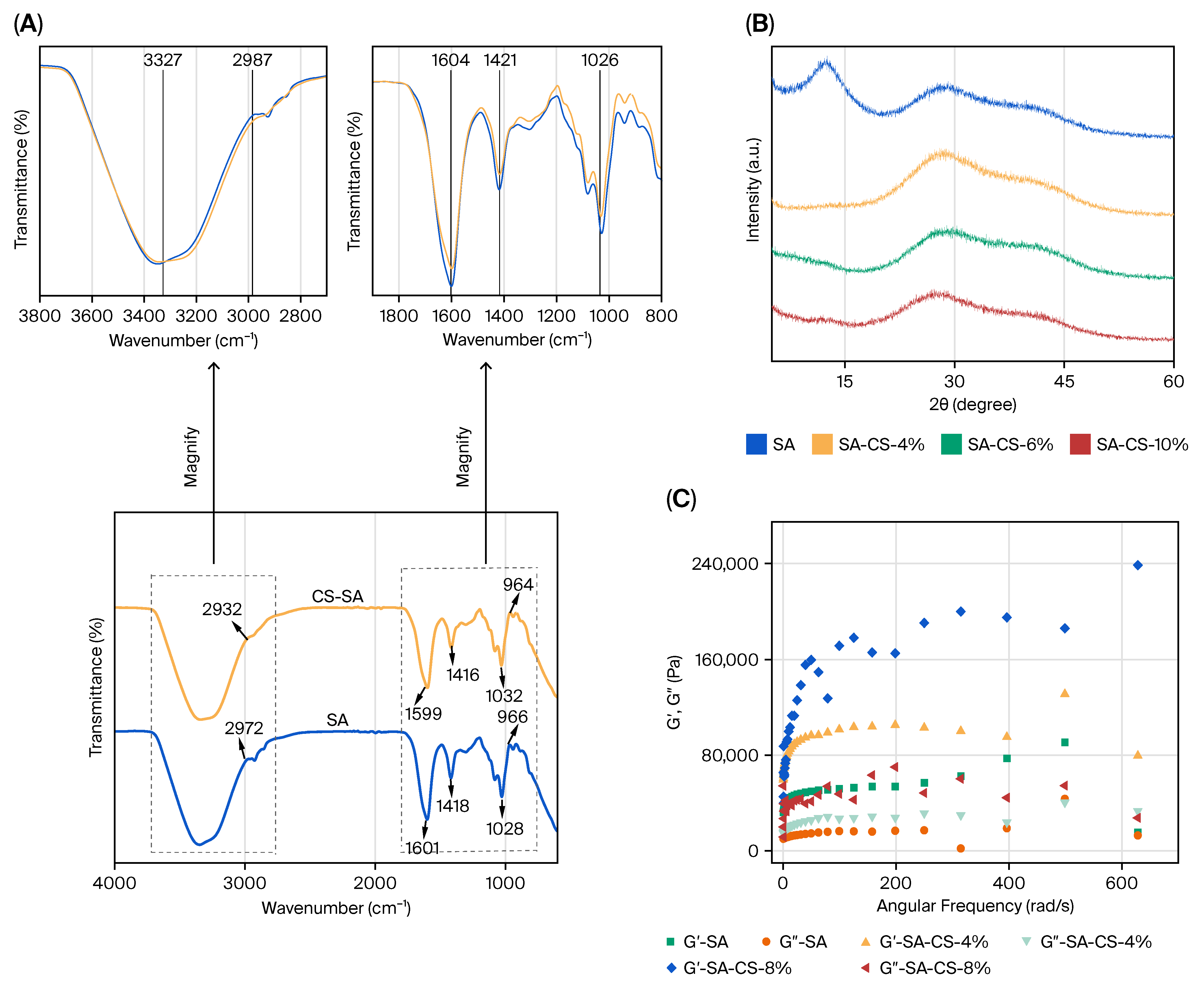

2.2. Characterization of CS/SA Composite Hydrogels

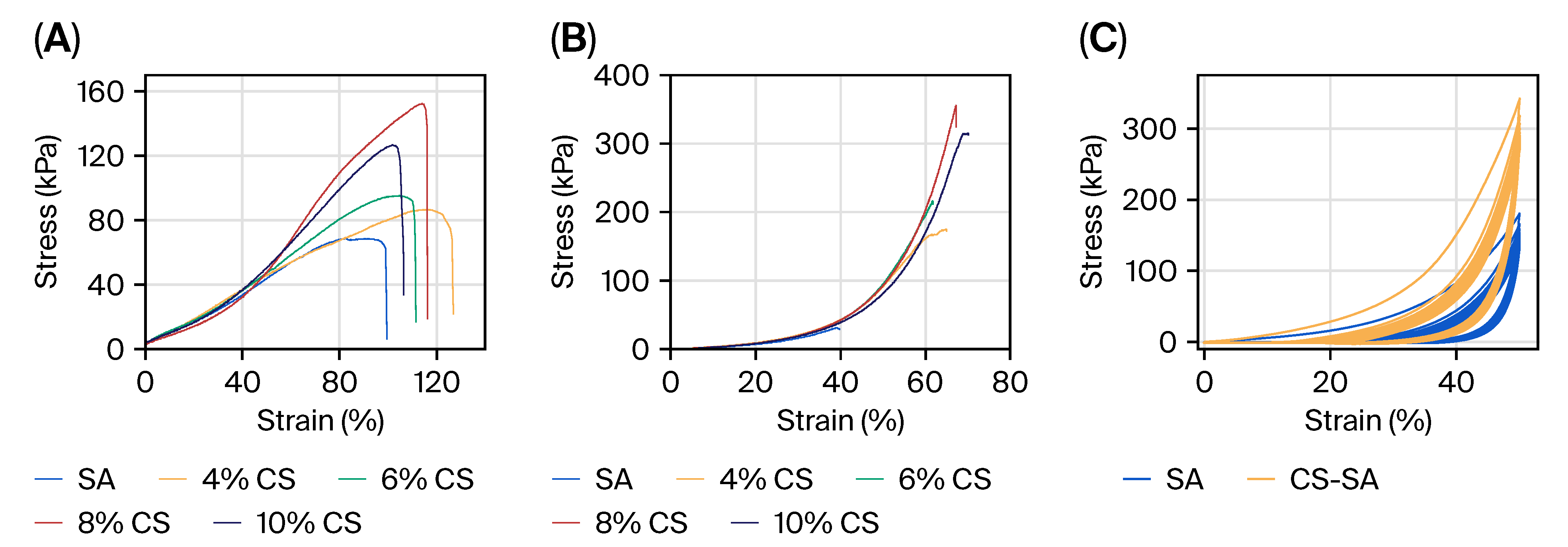

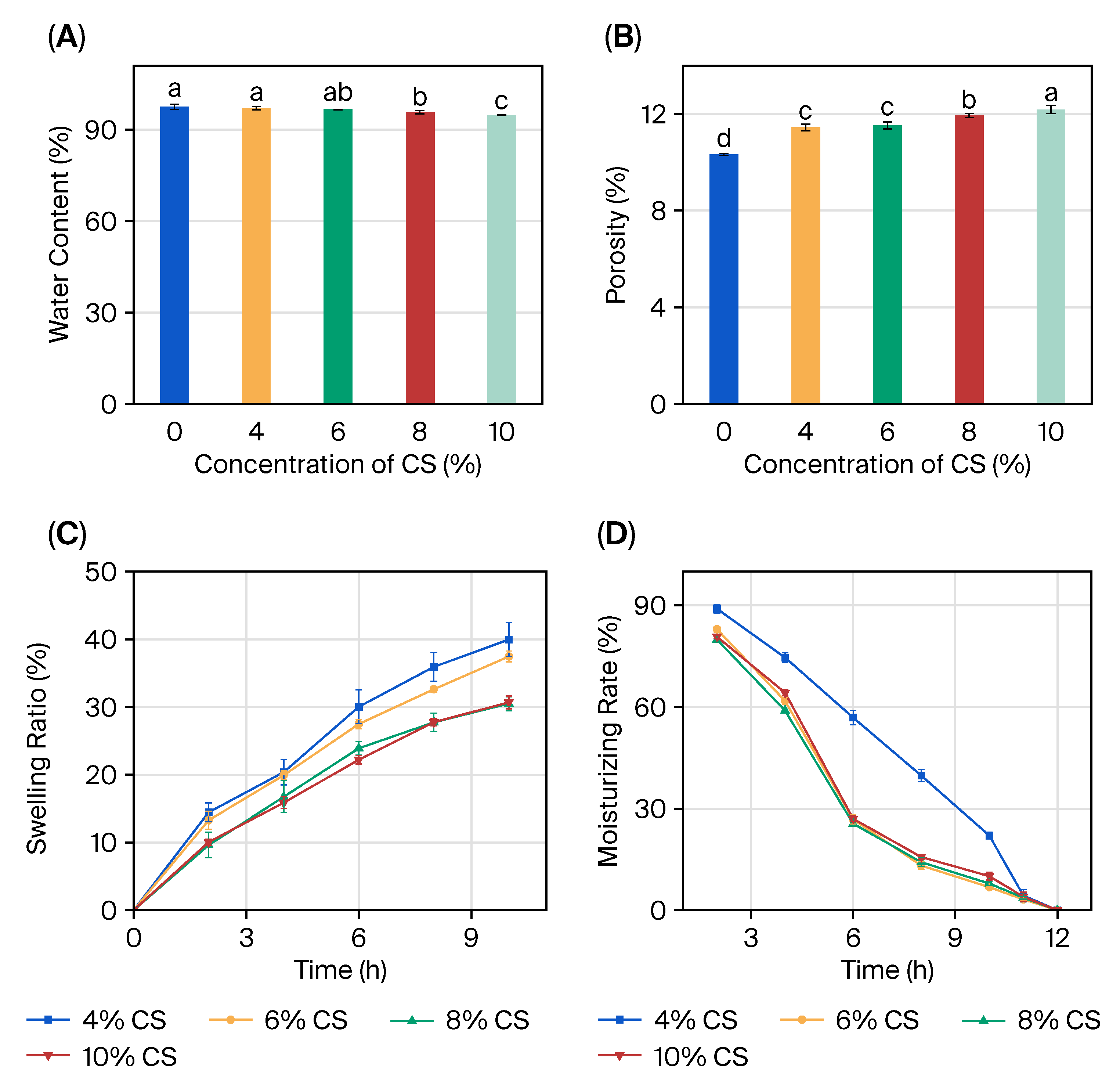

2.3. Physical Property Enhancement

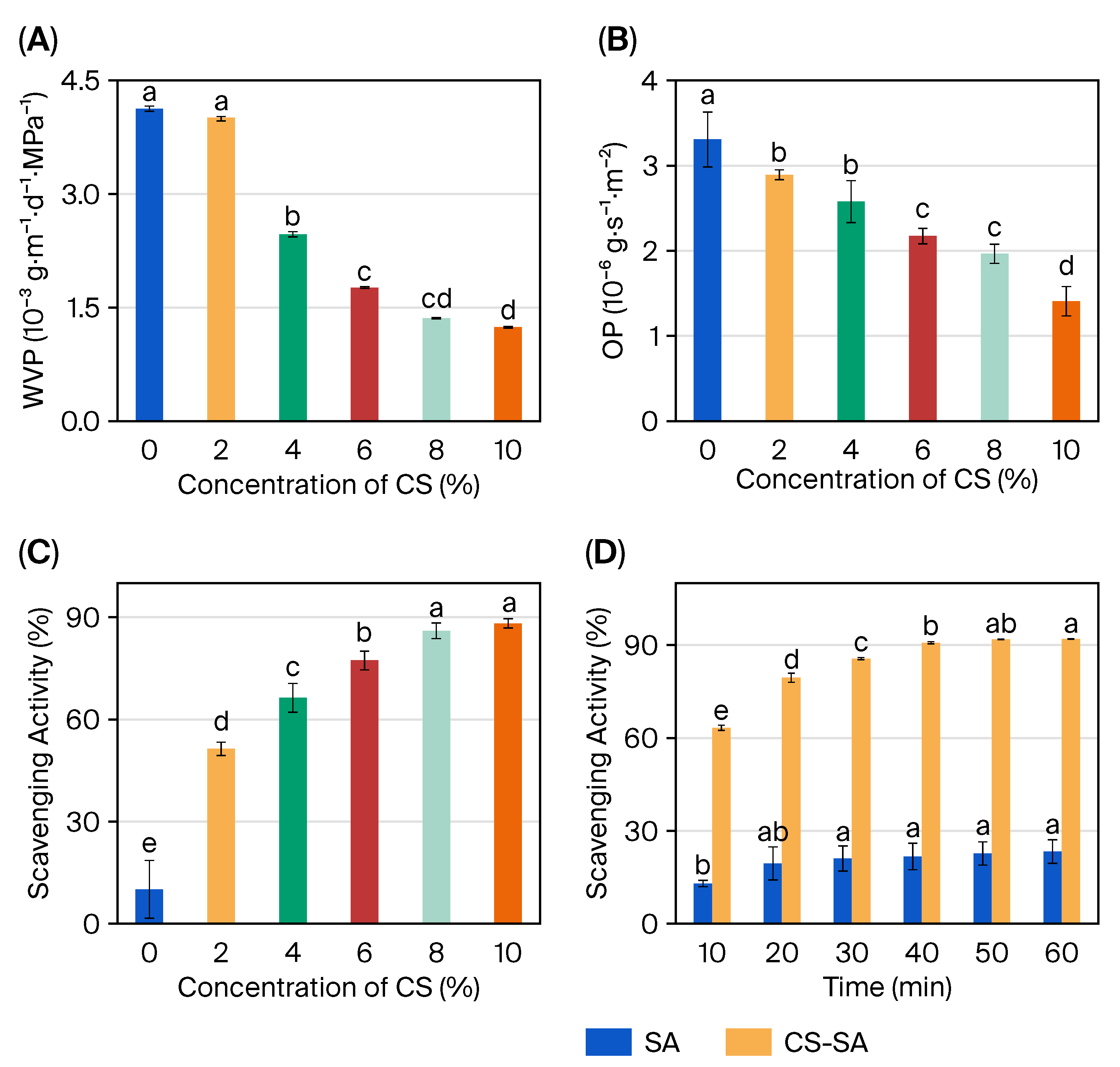

2.4. Barrier Properties and Functional Performance

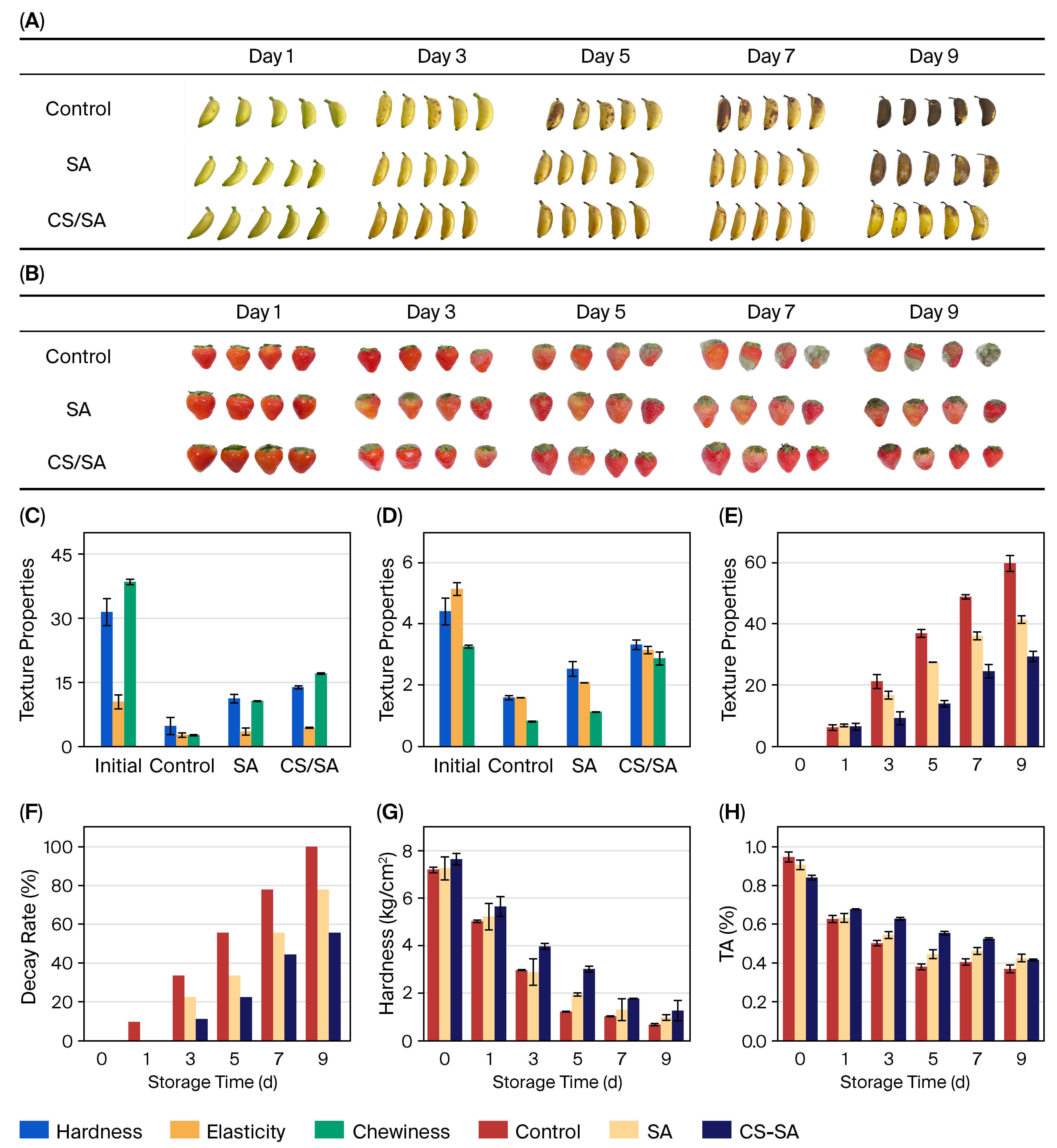

2.5. Practical Application in Fruit Preservation

2.6. Scalability and Industrial Implementation Considerations

- Temperature dependence: The behavior of the film at elevated temperatures (e.g., 25–35 °C, along the supply chain pathway in the tropical application environment).

- Effect of humidity: Variations in water vapor sorption and mechanical properties of the film under different humidity conditions (30 to 90% RH).

- Stability for dried film products: Stability of films at the pre-application stage, particularly the long-term stability of dried films stored prior to use for more than 6 months.

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Preparation of Hydrogel Films

4.2.1. Fabrication of Sodium Alginate (SA) Hydrogel Film

4.2.2. Fabrication of Camellia Saponin/Sodium Alginate (CS/SA) Hydrogel Films

4.3. Characterization of CS/SA Composite Hydrogel Films

- FTIR: Lyophilized samples were analyzed (4000–500 cm−1, 4 cm−1 resolution) using a Nicolet iS50 FTIR spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) with the KBr pellet method.

- SEM: Lyophilized CS/SA composite films were fractured in liquid nitrogen, gold-coated, and imaged at 200× magnification using a JSM-6390LV SEM (JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan).

- XRD: Patterns were recorded from 5 to 40 ° (2 θ) at 0.05 rad/s, using a D8 Advance diffractometer (Bruker, Karlsruhe, Germany) at 40 kV and 30 mA.

- Rheology: Storage () and loss () moduli were measured at 25 °C, using a Discovery HR-2 rheometer (TA Instruments, Milford, MA, USA), with frequency sweeps from 0.1 to 10 Hz at 0.1% strain.

4.4. Mechanical Property Assessment

4.5. Moisture Content and Swelling

4.6. Porosity of the SA and CS/SA Films

4.7. Thickness Measurement

4.8. Antioxidant Activity

4.9. Barrier Properties

4.9.1. Water Vapor Permeability (WVP)

4.9.2. Oxygen Permeability (OP)

4.10. Fruit Coating Test

4.11. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Springmann, M.; Clark, M.; Mason-D’Croz, D.; Wiebe, K.; Bodirsky, B.L.; Lassaletta, L.; De Vries, W.; Vermeulen, S.J.; Herrero, M.; Carlson, K.M.; et al. Options for keeping the food system within environmental limits. Nature 2018, 562, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fears, R.; ter Meulen, V.; von Braun, J. Global food and nutrition security needs more and new science. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaba2946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.; Nakano, K.; Kumar, S.; Katiyar, V. Edible packaging to prolong postharvest shelf-life of fruits and vegetables: A review. Food Chem. Adv. 2024, 4, 100711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Huang, X.; Li, Z.; Qin, Z.; Zhang, N.; Zhai, X.; Shi, J.; Zhang, J.; Shen, T.; Zhang, R.; et al. Application of Smart Packaging in Fruit and Vegetable Preservation: A Review. Foods 2025, 14, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, D.; Ni, Y.; Li, H.; Zhou, G.; Li, Y.; Xu, B. Antimicrobial mechanism of typical microbial preservatives and its potentiation strategy by photodynamic inactivation: A review. Food Microbiol. 2025, 132, 104833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, K.; Pang, G.; Duan, Y.; Onyeaka, H.; Krebs, J. Current research development on food contaminants, future risks, regulatory regime and detection technologies: A systematic literature review. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 381, 125246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akyuz, L.; Kaya, M.; Koc, B.; Mujtaba, M.; Ilk, S.; Labidi, J.; Salaberria, A.M.; Cakmak, Y.S.; Yildiz, A. Diatomite as a novel composite ingredient for chitosan film with enhanced physicochemical properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 105, 1401–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, K.; Jones, B.H. Roadmap to Biodegradable Plastics—Current State and Research Needs. Acs Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 6170–6187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.; Han, F.; Zhang, S.; Li, P.; Shang, N. Novel Bio-Based Materials and Applications in Antimicrobial Food Packaging: Recent Advances and Future Trends. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, S.C.; de Oliveira, T.V.; de Fátima Ferreira Soares, N.; Raymundo-Pereira, P.A. Sustainable and biodegradable polymer packaging: Perspectives, challenges, and opportunities. Food Chem. 2025, 470, 142652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Wu, B.; Yuan, P.; Liu, Y.; Hu, C. Research Progress of Sodium Alginate-Based Hydrogels in Biomedical Engineering. Gels 2025, 11, 758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senturk Parreidt, T.; Müller, K.; Schmid, M. Alginate-based edible films and coatings for food packaging applications. Foods 2018, 7, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, L.; Li, B.; Zhang, K.; Chu, X.; Hou, H. Physical properties and antioxidant activity of gelatin-sodium alginate edible films with tea polyphenols. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 118, 1377–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Hu, L.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, S.; Zheng, M.; Yu, Z.; Liu, K.; Zhou, Y. Gel Properties and Formation Mechanism of Camellia Oil Body-Based Oleogel Improved by Camellia Saponin. Gels 2022, 8, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, E.M. Hydrogel: Preparation, characterization, and applications: A review. J. Adv. Res. 2015, 6, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, B.; Wang, J.; Liu, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, D. Formation chitosan-based hydrogel film containing silicon for hops β-acids release as potential food packaging material. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 191, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, M.; Ruan, L.; Dong, X.; Tian, S.; Lang, W.; Wu, M.; Chen, Y.; Lv, Q.; Lei, L. Current state of knowledge on intelligent-response biological and other macromolecular hydrogels in biomedical engineering: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 227, 472–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhou, S.; Xia, X.; Tan, M.; Lv, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Tao, Y.; Lu, J.; Du, J.; Wang, H. High-performance carboxymethyl cellulose-based hydrogel film for food packaging and preservation system. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 223, 1126–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Gao, Y.; Yuan, M.; Zheng, Z.; Yin, J. Anti-Candida albicans Effects and Mechanisms of Theasaponin E1 and Assamsaponin A. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Wen, Y.; Yi, J.; Cao, Y.; Liu, F.; McClements, D.J. Comparison of natural and synthetic surfactants at forming and stabilizing nanoemulsions: Tea saponin, Quillaja saponin, and Tween 80. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019, 536, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeepipalli, S.P.K.; Du, B.; Sabitaliyevich, U.Y.; Xu, B. New insights into potential nutritional effects of dietary saponins in protecting against the development of obesity. Food Chem. 2020, 318, 126474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Li, C.; Hu, W.; Abdel-Samie, M.A.; Cui, H.; Lin, L. An overview of tea saponin as a surfactant in food applications. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 64, 12922–12934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malektaj, H.; Drozdov, A.D.; deClaville Christiansen, J. Mechanical Properties of Alginate Hydrogels Cross-Linked with Multivalent Cations. Polymers 2023, 15, 3012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinthong, T.; Yooyod, M.; Mahasaranon, S.; Viyoch, J.; Jongjitwimol, J.; Ross, S.; Ross, G. Designing Stable Macroporous Hydrogels: Effects of Single and Dual Surfactant Systems on Porous Architecture, Absorption Capacity, and Mechanical Strength. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2025, 7, 2497–2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, D.U.; Pareek, A.; Sharma, S.; Prajapati, B.G.; Thanawuth, K.; Sriamornsak, P. Alginate gels: Chemistry, gelation mechanisms, and therapeutic applications with a focus on GERD treatment. Int. J. Pharm. 2025, 675, 125570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Sui, J.; Yu, B.; Yuan, C.; Guo, L.; Abd El-Aty, A.M.; Cui, B. Alginate-based composites for environmental applications: A critical review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 49, 318–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lade, B.D.; Dhowlaghar, N.; Pillai, S.S.; Patil, B.S. Physicochemical, mechanical, and antimicrobial properties of sodium alginate films as carriers of zein emulsion with pelargonic acid and eugenol for active food packing. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2023, 40, 101202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tordi, P.; Ridi, F.; Samorì, P.; Bonini, M. Cation-Alginate Complexes and Their Hydrogels: A Powerful Toolkit for the Development of Next-Generation Sustainable Functional Materials. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2416390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Shen, B.; Zheng, C.; Huang, Y.; Liang, Y.; Fei, P.; Chen, J.; Lai, W. Chitosan/oxidized sodium alginate/Ca2+ hydrogels: Synthesis, characterization and adsorption properties. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 156, 110368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, H.; Lu, H.; Xu, X.; Shen, M. Sodium alginate-camellia seed cake protein active packaging film cross-linked by electrostatic interactions for fruit preservation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 288, 138627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.J.; Srebnik, S.; Rojas, O.J. Revisiting Cation Complexation and Hydrogen Bonding of Single-Chain Polyguluronate Alginate. Biomacromolecules 2021, 22, 4027–4036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulandari, W.; Islami, D.M.; Wellia, D.V.; Emriadi, E.; Sisca, V.; Jamarun, N. The Effect of Alginate Concentration on Crystallinity, Morphology, and Thermal Stability Properties of Hydroxyapatite/Alginate Composite. Polymers 2023, 15, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.P.; Packirisamy, G. Biopolymer based edible coating for enhancing the shelf life of horticulture products. Food Chem. Mol. Sci. 2022, 4, 100085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslami, Z.; Elkoun, S.; Robert, M.; Adjallé, K. A review of the effect of plasticizers on the physical and mechanical properties of alginate-based films. Molecules 2023, 28, 6637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshi, R.; Sauraj; Kumar, B.; Negi, Y.S. Chitosan films incorporated with citric acid and glycerol as an active packaging material for extension of green chilli shelf life. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 195, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.F.; Rezaei, M.; Zandi, M.; Ghavi, F.F. Preparation and functional properties of fish gelatin–chitosan blend edible films. Food Chem. 2013, 136, 1490–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazón, P.; Velazquez, G.; Ramírez, J.A.; Vázquez, M. Polysaccharide-based films and coatings for food packaging: A review. Food Hydrocoll. 2017, 68, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iñiguez-Moreno, M.; Ragazzo-Sánchez, J.A.; Barros-Castillo, C.; Montalvo-González, E.; Calderón-Santoyo, M. An extensive review of natural polymers used as coatings for postharvest shelf-life extension: Trends and challenges. Polymers 2021, 13, 3271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Dai, C.; Fan, L.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhou, Z.; Guan, P.; Tian, Y.; Xing, J.; Li, X.; et al. Injectable self-healing natural biopolymer-based hydrogel adhesive with thermoresponsive reversible adhesion for minimally invasive surgery. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2007457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, S.; Al-Harrasi, A.; Alhadhrami, A.S.; Al-Azri, M.S.; Ullah, S. Fabrication, characterization, and antioxidant potential of sodium alginate/acacia gum hydrogel-based films loaded with cinnamon essential oil. Gels 2023, 9, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Liu, R.; Zhang, C.; Meng, F.; Wang, L. Developing a green film from locust bean gum/carboxycellulose nanocrystal for fruit preservation. Future Foods 2021, 4, 100072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, W.; Lin, Z.; Tang, Z.; Lin, B. Carboxymethyl chitosan/sodium alginate hydrogel films with good biocompatibility and reproducibility by in situ ultra-fast crosslinking for efficient preservation of strawberry. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 316, 121073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasti, T.; Dixit, S.; Hiremani, V.D.; Chougale, R.B.; Masti, S.P.; Vootla, S.K.; Mudigoudra, B.S. Chitosan/pullulan based films incorporated with clove essential oil loaded chitosan-ZnO hybrid nanoparticles for active food packaging. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 277, 118866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivas, G.; Barbosa-Cánovas, G. Alginate–calcium films: Water vapor permeability and mechanical properties as affected by plasticizer and relative humidity. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2008, 41, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, M.; Albors, A.; Chiralt, A.; González-Martínez, C. Characterization of chitosan–oleic acid composite films. Food Hydrocoll. 2009, 23, 536–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanbarzadeh, B.; Almasi, H.; Entezami, A.A. Physical properties of edible emulsified films based on carboxymethyl cellulose and oleic acid. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2011, 48, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wang, X.; Chen, J.; Liu, C.; Li, T.; McClements, D.J.; Dai, T.; Liu, J. Antioxidant activity of proanthocyanidins-rich fractions from Choerospondias axillaris peels using a combination of chemical-based methods and cellular-based assay. Food Chem. 2016, 208, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Xing, H.; Chen, X. Anti-inflammatory and analgesic activities of the hydrolyzed sasanquasaponins from the defatted seeds of Camellia oleifera. Arch. Pharmacal Res. 2013, 36, 941–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, M.; Ju, X.; Zhang, H.; Xia, N.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Rayan, A.M. Physico-Chemical Characteristics of pH-Driven Active Film Loaded with Curcumin/Egg White Protein for Food Preservation. Foods 2024, 13, 1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; Wang, B.J.; Weng, Y.M. Preparation and characterization of mung bean starch edible films using citric acid as cross-linking agent. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2022, 32, 100845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, J.D.; Biviano, M.; Dagastine, R.R. Poroelastic properties of hydrogel microparticles. Soft Matter 2020, 16, 5314–5324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Gong, X.; Miao, Y.; Guo, X.; Liu, C.; Fan, Y.Y.; Zhang, J.; Niu, B.; Li, W. Preparation and characterization of multilayer films composed of chitosan, sodium alginate and carboxymethyl chitosan-ZnO nanoparticles. Food Chem. 2019, 283, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghani, A.; Zare, E.N.; Makvandi, P.; Rabiee, N. Antioxidant, antibacterial and biodegradable hydrogel films from carboxymethyl tragacanth gum and clove extract: Potential for wound dressings application. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2024, 7, 100428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, L.; Deng, J.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Chen, B.; Ma, Y.; Li, X.; Xu, B. Improving the functionality of chitosan-based packaging films by crosslinking with nanoencapsulated clove essential oil. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 192, 627–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xie, Y.; Ge, H.; Chen, L.; Wang, J.; Zhang, S.; Guo, Y.; Li, Z.; Feng, X. Physical properties and antioxidant capacity of chitosan/epigallocatechin-3-gallate films reinforced with nano-bacterial cellulose. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 179, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Initial CS Solution Concentration (% w/v) | Young’s Modulus (MPa) | Elongation at Break (%) |

|---|---|---|

| SA | 1.58 ± 0.12 | 99.6 ± 8.33 |

| CS/SA-1.3% CS | 0.97 ± 0.11 | 126.9 ± 10.36 |

| CS/SA-1.9% CS | 1.34 ± 0.09 | 111.4 ± 9.23 |

| CS/SA-2.5% CS | 0.82 ± 0.07 | 116.33 ± 7.14 |

| CS/SA-3.1% CS | 1.09 ± 0.06 | 106.53 ± 8.58 |

| Hydrogel Type | CS Concentration (%) | Film Thickness (mm) |

|---|---|---|

| SA | 0 | 0.063 ± 0.004 |

| CS/SA-1.3% CS | 4 | 0.062 ± 0.006 |

| CS/SA-1.9% CS | 6 | 0.060 ± 0.003 |

| CS/SA-2.5% CS | 8 | 0.057 ± 0.002 |

| CS/SA-3.1% CS | 10 | 0.056 ± 0.005 |

| Hydrogel Type | Water Solubility (%) | Moisturizing Rate (%) | Moisture Content (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SA | 34.92 ± 0.07 | 0.8898 ± 0.013 | 0.9747 ± 0.008 |

| CS/SA | 63.89 ± 0.02 | 0.7991 ± 0.004 | 0.9475 ± 0.002 |

| Film Material | Method | WVP | OP | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (10−6g−1·m−1·s−1·kPa−1) | (cm3m·m−2·d−1·kPa−1) | |||

| CS/SA (This Work) | Spray | 1.30 ± 0.15 | 1.9 ± 0.25 | – |

| Pure Sodium Alginate | Spray | 4.10 ± 0.14 | 3.30 ± 0.31 | – |

| Pure Sodium Alginate | Casting | 2.65 ± 0.12 | 5.20 ± 0.45 | [44] |

| Pure Chitosan | Casting | 1.92 ± 0.08 | 4.80 ± 0.30 | [45] |

| CMC | Casting | 1.54 ± 0.05 | 12.50 ± 1.20 | [46] |

| Initial CS Concentration (w/v) | Mass of CS (g in 100 mL) | wt% of CS in Air-Dried Film |

|---|---|---|

| 0% | 0 | 0% |

| 4% | 4 | 1.3% |

| 6% | 6 | 1.9% |

| 8% | 8 | 2.5% |

| 10% | 10 | 3.1% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hu, L.; Rao, H.; Zhu, B.; Du, M.; Xu, K.; Gao, H. Camellia Saponin-Enhanced Sodium Alginate Hydrogels for Sustainable Fruit Preservation. Gels 2025, 11, 1012. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11121012

Hu L, Rao H, Zhu B, Du M, Xu K, Gao H. Camellia Saponin-Enhanced Sodium Alginate Hydrogels for Sustainable Fruit Preservation. Gels. 2025; 11(12):1012. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11121012

Chicago/Turabian StyleHu, Lisong, Hongdan Rao, Borong Zhu, Menghao Du, Keqin Xu, and Haili Gao. 2025. "Camellia Saponin-Enhanced Sodium Alginate Hydrogels for Sustainable Fruit Preservation" Gels 11, no. 12: 1012. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11121012

APA StyleHu, L., Rao, H., Zhu, B., Du, M., Xu, K., & Gao, H. (2025). Camellia Saponin-Enhanced Sodium Alginate Hydrogels for Sustainable Fruit Preservation. Gels, 11(12), 1012. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11121012