Being a Target for Glycation by Methylglyoxal Contributes to Therapeutic Efficacy of Injectable Collagen Hydrogels Post-Myocardial Infarction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

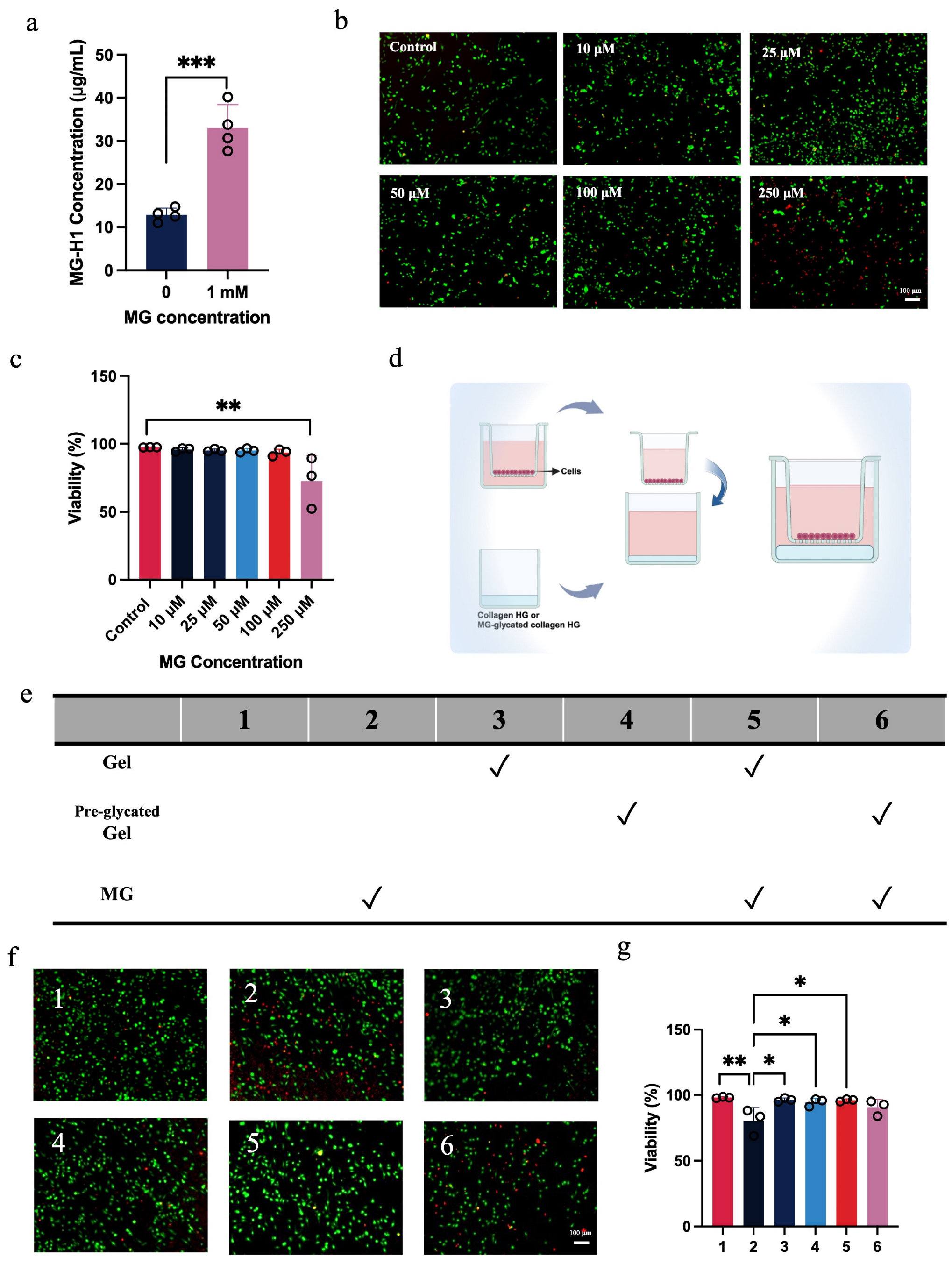

2.1. Glycated Collagen Hydrogel Fails to Protect Macrophages from Methylglyoxal-Induced Cytotoxicity

2.2. Glycated Collagen Hydrogel Fails to Improve Cardiac Function Post-MI

2.3. Greater Scar Formation and Less Preservation of Cardiac Muscle After Glycated Collagen Hydrogel Treatment

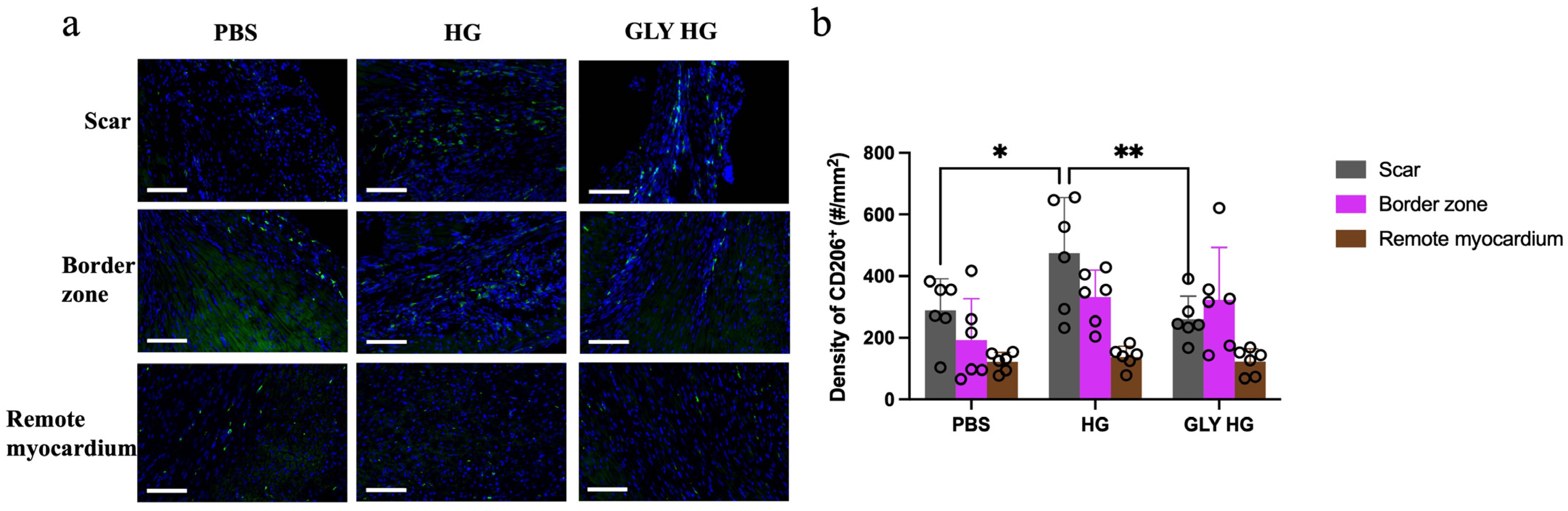

2.4. Collagen Hydrogel Enhances M2 Macrophage Recruitment in the Scar

2.5. Discussion

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Preparation of the Collagen Hydrogel

4.2. ELISA Analysis

4.3. Cell Culture and Viability Assay

4.4. Myocardial Infarction Model

4.5. Echocardiography

4.6. Histology and Immunohistochemistry

4.7. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Di Cesare, M.; McGhie, D.V.; Perel, P.; Mwangi, J.; Taylor, S.; Pervan, B.; Kabudula, C.; Narula, J.; Bixby, H.; Pineiro, D.; et al. The heart of the world. Glob. Heart 2024, 19, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spadaccio, C.; Benedetto, U. Coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) vs. percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in the treatment of multivessel coronary disease: Quo vadis?—A review of the evidences on coronary artery disease. Ann. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2018, 7, 506–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kageyama, S.; Serruys, P.W.; Ninomiya, K.; O’Leary, N.; Masuda, S.; Kotoku, N.; Colombo, A.; van Geuns, R.J.; Milojevic, M.; Mack, M.J.; et al. Impact of on-pump and off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting on 10-year mortality versus percutaneous coronary intervention. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2023, 64, ezad240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chua, T.K.T.; Gao, F.; Chia, S.Y.; Sin, K.Y.K.; Naik, M.J.; Tan, T.E.; Tham, Y.C. Long-term mortality after isolated coronary artery bypass grafting and risk factors for mortality. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2024, 19, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, C.; Li, Y.; Ma, J.; Niu, L.; Tay, F.R. Clinical/translational aspects of advanced glycation end-products. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2019, 30, 959–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhujaily, M. Molecular assessment of methylglyoxal-induced toxicity and therapeutic approaches in various diseases: Exploring the interplay with the glyoxalase system. Life 2024, 14, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rungratanawanich, W.; Qu, Y.; Wang, X.; Essa, M.M.; Song, B.J. Advanced glycation end products (AGEs) and other adducts in aging-related diseases and alcohol-mediated tissue injury. Exp. Mol. Med. 2021, 53, 168–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh-Kader, A.; Houreld, N.N.; Rajendran, N.K.; Abrahamse, H. The link between advanced glycation end products and apoptosis in delayed wound healing. Cell Biochem. Funct. 2019, 37, 432–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldin, A.; Beckman, J.A.; Schmidt, A.M.; Creager, M.A. Advanced glycation end products: Sparking the development of diabetic vascular injury. Circulation 2006, 114, 597–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabbani, N.; Thornalley, P.J. Methylglyoxal, glyoxalase 1 and the dicarbonyl proteome. Amino Acids 2012, 42, 1133–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, N.J.R.; Vulesevic, B.; McNeill, B.; Cimenci, C.E.; Ahmadi, A.; Gonzalez-Gomez, M.; Ostojic, A.; Zhong, Z.; Brownlee, M.; Beisswenger, P.J.; et al. Methylglyoxal-derived advanced glycation end products contribute to negative cardiac remodeling and dysfunction post-myocardial infarction. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2017, 112, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cimenci, C.E.; Blackburn, N.J.R.; Sedlakova, V.; Pupkaite, J.; Munoz, M.; Rotstein, B.H.; Spiegel, D.A.; Alarcon, E.I.; Suuronen, E.J. Combined methylglyoxal scavenger and collagen hydrogel therapy prevents adverse remodeling and improves cardiac function post-myocardial infarction. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2108630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heber, S.; Haller, P.M.; Kiss, A.; Jäger, B.; Huber, K.; Fischer, M.J.M. Association of plasma methylglyoxal increase after myocardial infarction and the left ventricular ejection fraction. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, C.; Liu, W.; Long, L.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, W.; He, S.; Lu, L.; Fan, H.; Yang, L.; Wang, Y. Regeneration of infarcted hearts by myocardial infarction-responsive injectable hydrogels with combined anti-apoptosis, anti-inflammatory and pro-angiogenesis properties. Biomaterials 2022, 290, 121849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, S.; McNeill, B.; Podrebarac, J.; Hosoyama, K.; Sedlakova, V.; Cron, G.; Smyth, D.; Seymour, R.; Goel, K.; Liang, W.; et al. Injectable human recombinant collagen matrices limit adverse remodeling and improve cardiac function after myocardial infarction. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roser, S.M.; Munarin, F.; Polucha, C.; Minor, A.J.; Choudhary, G.; Coulombe, K.L.K. Customized heparinized alginate and collagen hydrogels for tunable, local delivery of angiogenic proteins. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2025, 11, 1612–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, S.; Sedlakova, V.; Zhang, Q.; McNeill, B.; Smyth, D.; Seymour, R.; Davis, D.R.; Ruel, M.; Brand, M.; Alarcon, E.I.; et al. Recombinant human collagen hydrogel rapidly reduces methylglyoxal adducts within cardiomyocytes and improves borderzone contractility after myocardial infarction in mice. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2204076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, H.L. Extracellular Matrix and Ageing. In Biochemistry and Cell Biology of Ageing: Part I Biomedical Science; Harris, J.R., Korolchuk, V.I., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 169–190. ISBN 978-981-13-2835-0. [Google Scholar]

- Nowotny, K.; Castro, J.P.; Hugo, M.; Braune, S.; Weber, D.; Pignitter, M.; Somoza, V.; Bornhorst, J.; Schwerdtle, T.; Grune, T. Oxidants produced by methylglyoxal-modified collagen trigger er stress and apoptosis in skin fibroblasts. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2018, 120, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, N.J.R.; Sofrenovic, T.; Kuraitis, D.; Ahmadi, A.; McNeill, B.; Deng, C.; Rayner, K.J.; Zhong, Z.; Ruel, M.; Suuronen, E.J. Timing underpins the benefits associated with injectable collagen biomaterial therapy for the treatment of myocardial infarction. Biomaterials 2015, 39, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prantner, D.; Vogel, S.N. Intracellular methylglyoxal accumulation in classically activated mouse macrophages is mediated by HIF-1α. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2025, 117, qiae215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluijmert, N.J.; Atsma, D.E.; Quax, P.H.A. Post-ischemic myocardial inflammatory response: A complex and dynamic process susceptible to immunomodulatory therapies. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 647785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jian, Y.; Zhou, X.; Shan, W.; Chen, C.; Ge, W.; Cui, J.; Yi, W.; Sun, Y. Crosstalk between macrophages and cardiac cells after myocardial infarction. Cell Commun. Signal. 2023, 21, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuo, X.; Xiao, Y.; Yang, J.; He, Y.; He, Y.; Liu, K.; Chen, X.; Guo, J. Engineering collagen-based biomaterials for cardiovascular medicine. Collagen Leather 2024, 6, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.-q.; Peng, S.; Song, Z.-y.; Lin, S. Collagen biomaterial for the treatment of myocardial infarction: An update on cardiac tissue engineering and myocardial regeneration. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2019, 9, 920–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majid, Q.A.; Fricker, A.T.R.; Gregory, D.A.; Davidenko, N.; Hernandez Cruz, O.; Jabbour, R.J.; Owen, T.J.; Basnett, P.; Lukasiewicz, B.; Stevens, M.; et al. Natural biomaterials for cardiac tissue engineering: A highly biocompatible solution. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2020, 7, 554597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Zhang, Z.; Luo, R.; Jiang, Q.; Yang, L.; Wang, Y. Advances in injectable hydrogel strategies for heart failure treatment. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2023, 12, e2300029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Mordechai, T.; Kain, D.; Holbova, R.; Landa, N.; Levin, L.P.; Elron-Gross, I.; Glucksam-Galnoy, Y.; Feinberg, M.S.; Margalit, R.; Leor, J. Targeting and modulating infarct macrophages with hemin formulated in designed lipid-based particles improves cardiac remodeling and function. J. Control. Release 2017, 257, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezold, V.; Rosenstock, P.; Scheffler, J.; Geyer, H.; Horstkorte, R.; Bork, K. Glycation of macrophages induces expression of pro-inflammatory and reduces phagocytic efficiency. Aging 2019, 11, 5258–5275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Wang, W.; Zhu, J.; Chen, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Liu, D.; Yang, P.; Liu, Y. Methylglyoxal deteriorates macrophage efferocytosis in diabetic wounds through ROS-induced ubiquitination degradation of KLF4. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2025, 231, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvin, N.; Joo, S.W.; Mandal, T.K. Injectable biopolymer-based hydrogels: A next-generation platform for minimally invasive therapeutics. Gels 2025, 11, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talior-Volodarsky, I.; Connelly, K.A.; Arora, P.D.; Gullberg, D.; McCulloch, C.A. A11 integrin stimulates myofibroblast differentiation in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc. Res. 2012, 96, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Guo, X.; Ileri, R.; Ruel, M.; Alarcon, E.I.; Suuronen, E.J. Being a Target for Glycation by Methylglyoxal Contributes to Therapeutic Efficacy of Injectable Collagen Hydrogels Post-Myocardial Infarction. Gels 2026, 12, 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010018

Guo X, Ileri R, Ruel M, Alarcon EI, Suuronen EJ. Being a Target for Glycation by Methylglyoxal Contributes to Therapeutic Efficacy of Injectable Collagen Hydrogels Post-Myocardial Infarction. Gels. 2026; 12(1):18. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010018

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuo, Xixi, Ramis Ileri, Marc Ruel, Emilio I. Alarcon, and Erik J. Suuronen. 2026. "Being a Target for Glycation by Methylglyoxal Contributes to Therapeutic Efficacy of Injectable Collagen Hydrogels Post-Myocardial Infarction" Gels 12, no. 1: 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010018

APA StyleGuo, X., Ileri, R., Ruel, M., Alarcon, E. I., & Suuronen, E. J. (2026). Being a Target for Glycation by Methylglyoxal Contributes to Therapeutic Efficacy of Injectable Collagen Hydrogels Post-Myocardial Infarction. Gels, 12(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010018