CO2-Induced Foaming and Gelation for the Fabrication of Macroporous Alginate Aerogel Scaffolds

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

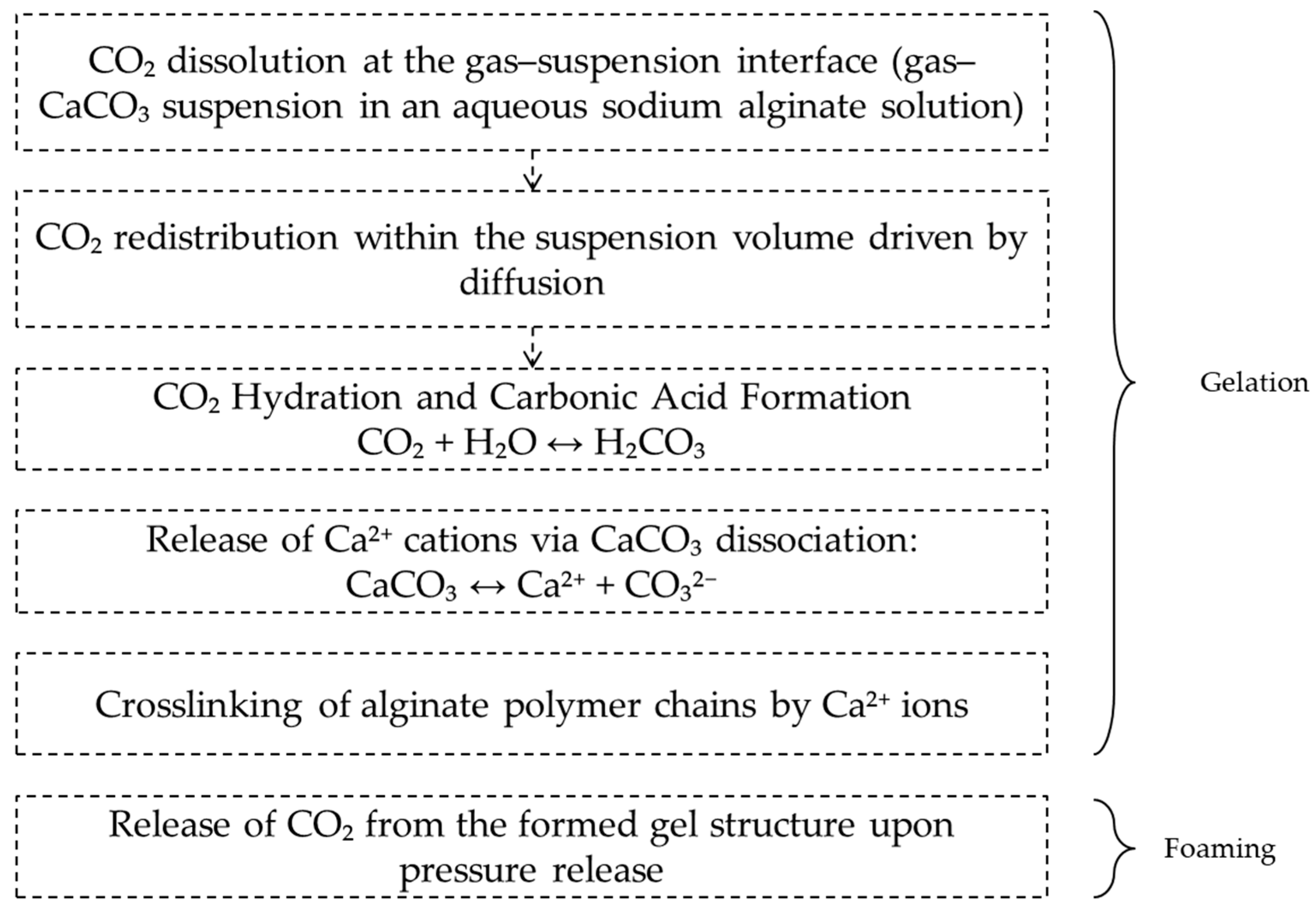

2.1. Mechanism of CO2-Induced Gelation and Foaming in the Alginate–CaCO3 System

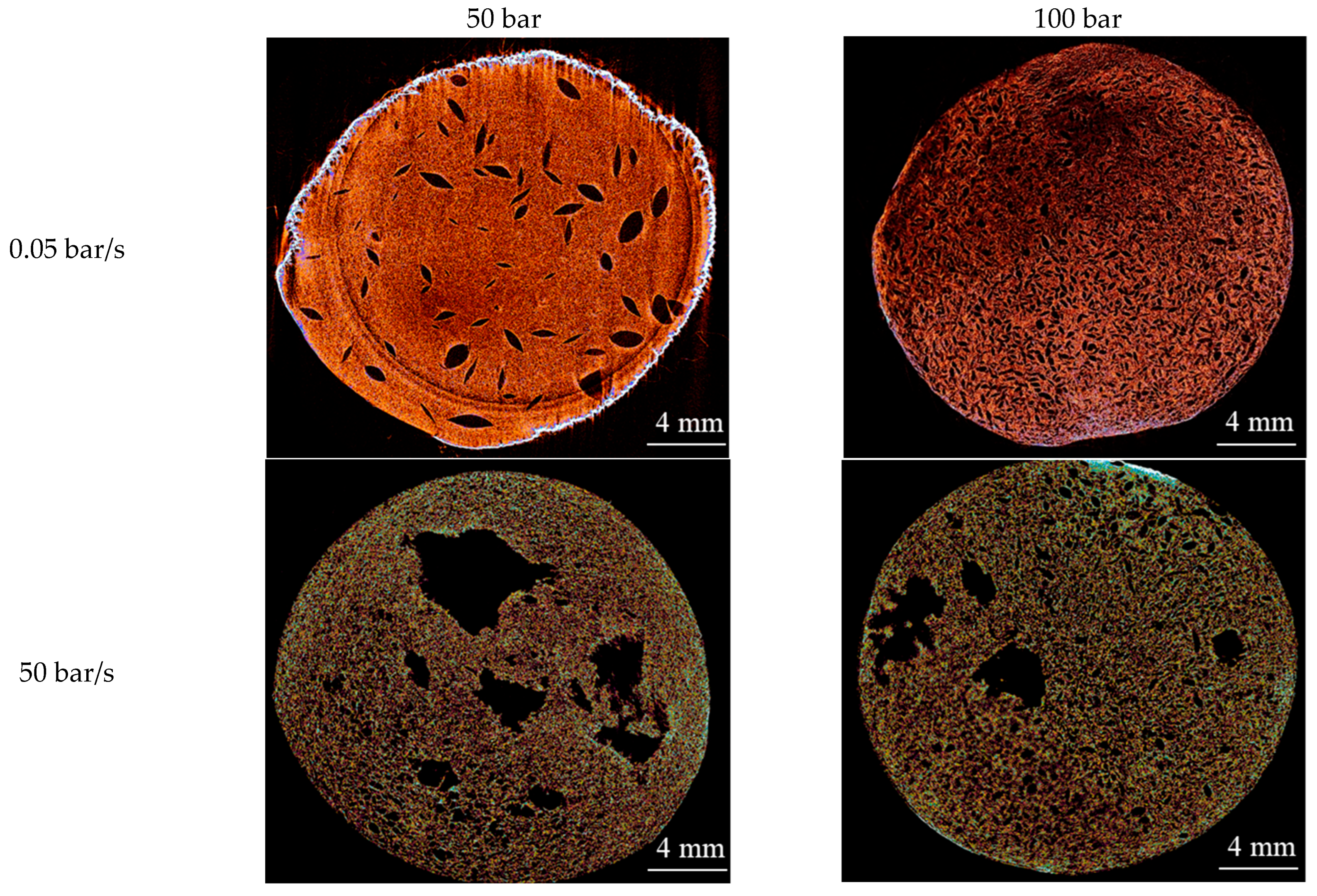

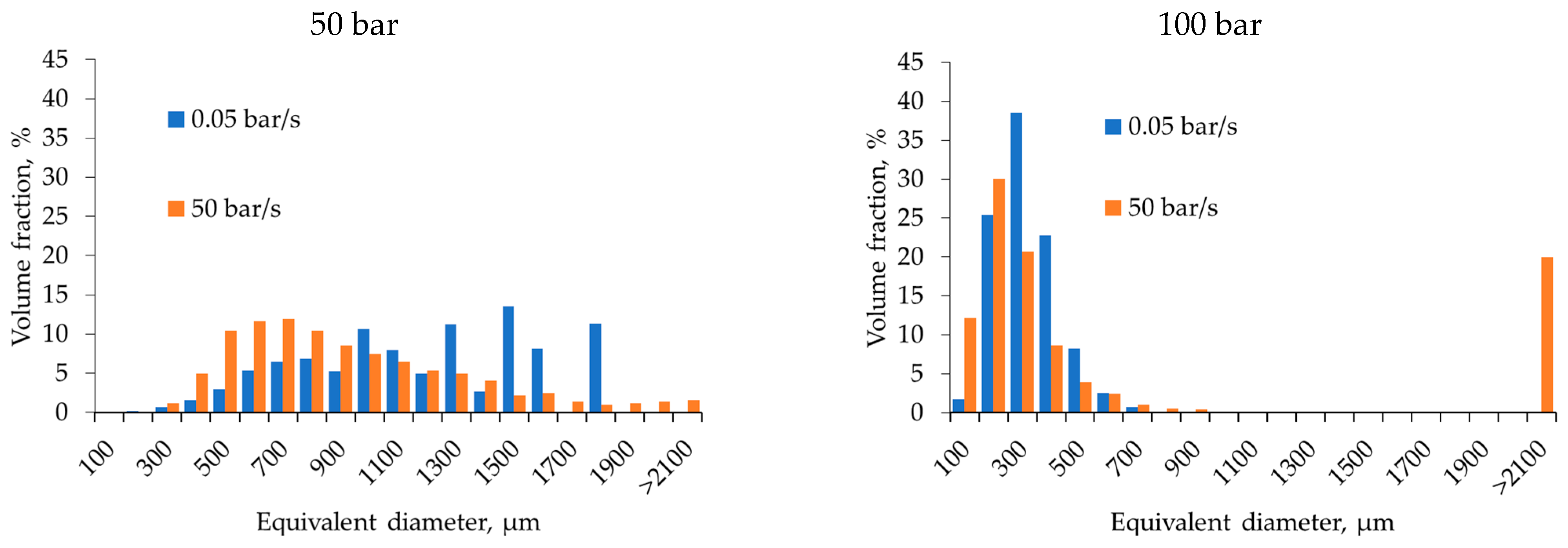

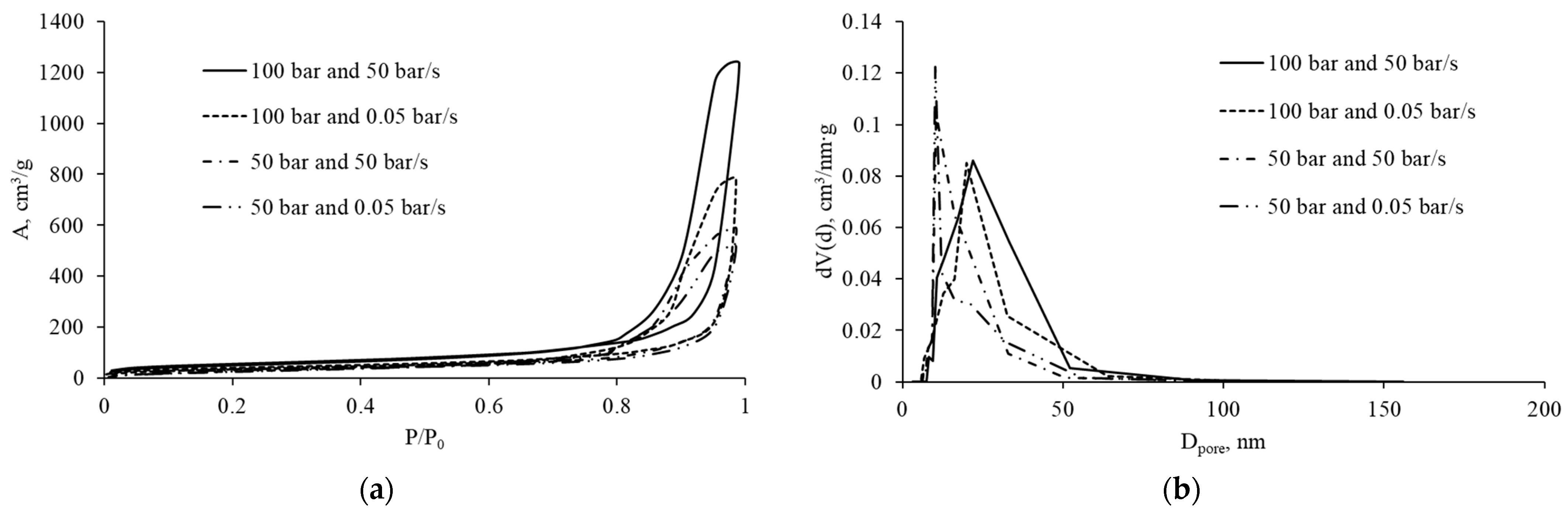

2.2. Effect of Pressure and Depressurization Rate

2.3. Effect of Process Temperature, Pulsed Pressure Changes, and Surfactant Addition

- Lowering the process temperature. Reducing the foaming temperature increases CO2 solubility in the aqueous system, increases the viscosity of the dispersion medium, and slows diffusion. It is expected to further narrow the macropore size distribution and shift the average mesopore size toward smaller diameters due to more “complete” crosslinking during prolonged residence in the low-pH region.

- Pulsed pressure variation during foaming. Pulsed changes in pressure can promote the formation of elongated anisotropic pores. Such anisotropic pores are attractive for guided growth of nerve, muscle, or endothelial structures.

- Addition of a surfactant (SAA). Surfactant addition can affect the critical nucleus radius by lowering interfacial tension and influence the stability of thin walls between forming pores. In addition, low concentrations of biocompatible surfactants can increase the density of nucleation sites.

2.3.1. Effect of Process Temperature

2.3.2. Effect of Pulsed Pressure Changes

2.3.3. Effect of Surfactant Addition

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Methods

4.2.1. Alginate Dispersion Preparation

4.2.2. CO2 Foaming Process

4.2.3. Supercritical CO2 Drying

4.3. Analytical Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thakare, N.R.; Hazarika, S. Eco-friendly biopolymers and their biomedical applications: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 327, 147225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, J.; McClements, D.J.; Luo, S.; Liu, C.; Ye, J. Advances of biopolymer-based emulsion gels: Fabrication, design, and application. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 165, 105335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, Y.; Li, S.; Li, X.; He, M.; Wu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Hu, J.; Mai, X. Aerogels of Cellulose Nanofibers@Metal-Organic Frameworks for Carbon Dioxide Capture. Eng. Sci. 2025, 36, 1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghani, F.; Annabi, N. Engineering porous scaffolds using gas-based techniques. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2011, 22, 661–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menshutina, N.V.; Uvarova, A.A.; Mochalova, M.S.; Lovskaya, D.D.; Tsygankov, P.Y.; Gurina, O.I.; Zubkov, E.A.; Abramova, O.V. Biopolymer Aerogels as Nasal Drug Delivery Systems. Russ. J. Phys. Chem. B 2023, 17, 1507–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, O.; Powell, C.; Solorio, L.; Krebs, M.; Alsberg, E. Affinity-based growth factor delivery using biodegradable, photocrosslinked heparin-alginate hydrogels. J. Control. Release 2011, 154, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karageorgiou, V.; Kaplan, D. Porosity of 3D biomaterial scaffolds and osteogenesis. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 5474–5491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.; Lian, M.; Wu, Q.; Qiao, Z.; Sun, B.; Dai, K. Effect of Pore Size on Cell Behavior Using Melt Electrowritten Scaffolds. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 629270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djemaa, I.; Andrieux, S.; Auguste, S.; Jacomine, L.; Tarnowska, M.; Drenckhan-Andreatta, W. One-Step Generation of Alginate-Based Hydrogel Foams Using CO2 for Simultaneous Foaming and Gelation. Gels 2022, 8, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepika, D.; Jagadeeshbabu, J.P. Sacrificial Polystyrene Template Assisted Synthesis of Tunable Pore Size Hollow Core-Shell Silica Nanoparticles (HCSNs) for Drug Delivery Application. AIP Conf. Proc. 2019, 2148, 030016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Rosales, V.; Ardao, I.; Alvarez-Lorenzo, C.; Ribeiro, N.; Oliveira, A.L.; García-González, C.A. Sterile and Dual-Porous Aerogels Scaffolds Obtained through a Multistep Supercritical CO2-Based Approach. Molecules 2019, 24, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos-Rosales, V.; Alvarez-Rivera, G.; Hillgärtner, M.; Cifuentes, A.; Itskov, M.; García-González, C.A.; Rege, A. Stability Studies of Starch Aerogel Formulations for Biomedical Applications. Biomacromolecules 2020, 21, 5336–5344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, M.; Yang, X.; Zhu, Y.; Guerin, G.; Zhang, S. Ultralight Aerogels with Hierarchical Porous Structures Prepared from Cellulose Nanocrystal Stabilized Pickering High Internal Phase Emulsions. Langmuir 2020, 36, 6421–6428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceccaldi, C.; Bushkalova, R.; Cussac, D.; Duployer, B.; Tenailleau, C.; Bourin, P.; Parini, A.; Sallerin, B.; Girod Fullana, S. Elaboration and Evaluation of Alginate Foam Scaffolds for Soft Tissue Engineering. Int. J. Pharm. 2017, 524, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catanzano, O.; Soriente, A.; La Gaa, A.; Cammarota, M.; Ricci, G.; Fasolino, I.; Schiraldi, C.; Ambrosio, L.; Malinconico, M.; Laurienzo, P.; et al. Macroporous Alginate Foams Crosslinked with Strontium for Bone Tissue Engineering. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 202, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Li, D.; Tang, M.; Ma, H.; Gui, Y.; Tian, X.; Quan, F.; Song, X.; Xia, Y. Alginate-Based Hierarchical Porous Carbon Aerogel for High-Performance Supercapacitors. J. Alloys Compd. 2018, 749, 517–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menshutina, N.; Fedotova, O.; Abramov, A.; Golubev, E.; Sulkhanov, Y.; Tsygankov, P. Processes of Obtaining Nanostructured Materialswith a Hierarchical Porous Structure on the Example of Alginate Aerogels. Gels 2024, 10, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, M. Technical development and application of supercritical CO2 foaming technology in PCL foam production. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 6825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valor, D.; Montes, A.; Monteiro, M.; García-Casas, I.; Pereyra, C.; Martínez de la Ossa, E. Determining the Optimal Conditions for the Production by Supercritical CO2 of Biodegradable PLGA Foams for the Controlled Release of Rutin as a Medical Treatment. Polymers 2021, 13, 1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanovich, M.A.; Di Maio, E.; Salerno, A. Current Trend and New Opportunities for Multifunctional Bio-Scaffold Fabrication via High-Pressure Foaming. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurki, A.; Paakinaho, K.; Hannula, M.; Hyttinen, J.; Miettinen, S.; Sartoneva, R. Ascorbic Acid 2-Phosphate-Releasing Supercritical Carbon Dioxide-Foamed Poly(L-Lactide-Co-epsilon-Caprolactone) Scaffolds Support Urothelial Cell Growth and Enhance Human Adipose-Derived Stromal Cell Proliferation and Collagen Production. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2023, 2023, 6404468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souto-Lopes, M.; Fernandes, M.H.; Monteiro, F.J.; Salgado, C.L. Bioengineering Composite Aerogel-Based Scaffolds That Influence Porous Microstructure, Mechanical Properties and In Vivo Regeneration for Bone Tissue Application. Materials 2023, 16, 4483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florea-Spiroiu, M.; Bala, D.; Balan, A.; Nichita, C.; Stamatin, I. Alginate matrices prepared in sub and supercritical CO2. Dig. J. Nanomater. Biostruct. 2012, 7, 1549–1555. [Google Scholar]

- Namiyut, A.Y. Solubility of Gases in Water: Reference Handbook; Nedra: Moscow, Russia, 1991; 167p. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond, L.; Akinfiev, N. Solubility of CO2 in water from −1.5 to 100 °C and from 0.1 to 100 MPa: Evaluation of literature data and thermodynamic modelling. Fluid Phase Equilibria 2003, 208, 265–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, H.H.; Chambon, F. Analysis of Linear Viscoelasticity of a Crosslinking Polymer at the Gel Point. J. Rheol. 1986, 30, 367–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, S.N.; Wong, A.; Guo, Q.; Park, C.B.; Zong, J.H. Change in the Critical Nucleation Radius and Its Impact on Cell Stability during Polymeric Foaming Processes. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2009, 64, 4899–4907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafi, M.A.; Flumerfelt, R.W. Initial Bubble Growth in Polymer Foam Processes. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1997, 52, 627–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venerus, D.C. Modeling Diffusion-Induced Bubble Growth in Polymer Liquids. Cell. Polym. 2003, 22, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breuer, R. Modeling Flow and Cell Formation in Foam Sheet Extrusion of Polystyrene with CO2 and Co-Blowing Agents. Part II: Process Model. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2021, 61, 1332–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venerus, D.C.; Yala, N.; Bernstein, B. Analysis of Diffusion-Induced Bubble Growth in Viscoelastic Liquids. J. Non-Newton. Fluid Mech. 1998, 75, 55–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tammaro, D.; Villone, M.M.; D’Avino, G.; Maffettone, P.L. An Experimental and Numerical Investigation on Bubble Growth in Polymeric Foams. Entropy 2022, 24, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, R.J. The Deborah and Weissenberg Numbers. Rheol. Bull. 2012, 53, 32–39. [Google Scholar]

- Lombardi, L.; Tammaro, D. Effect of Polymer Swell in Extrusion Foaming of Low-Density Polyethylene. Phys. Fluids 2021, 33, 033104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malektaj, H.; Drozdov, A.D.; deClaville Christiansen, J. Mechanical Properties of Alginate Hydrogels Cross-Linked with Multivalent Cations. Polymers 2023, 15, 3012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abramov, A.A.; Okisheva, M.K.; Tsygankov, P.Y.; Menshutina, N.V. Development of “Ink” for Extrusion Methods of 3D Printing with Viscous Materials. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2023, 93, 3264–3271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everitt, S.L.; Harlen, O.G.; Wilson, H.J. Bubble Growth in a Two-Dimensional Viscoelastic Foam. J. Non-Newton. Fluid Mech. 2006, 137, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramov, A.A.; Tsygankov, P.Y.; Golubev, E.V.; Menshutina, N.V. Formation of a hierarchical structure in aerogels based on sodium alginate using the foaming process in a carbon dioxide environment. Mod. High Tech. Reg. App. 2024, 68, 93–100. [Google Scholar]

- Menshutina, N.; Tsygankov, P.; Khudeev, I.; Lebedev, A. Methods of intensification of supercritical drying for obtaining aerogels. Dry. Technol. 2022, 40, 1278–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | SBET, m2/g | VBJH, cm3/g |

|---|---|---|

| 100 bar and 50 bar/s | 206 | 2.0 |

| 100 bar and 0.05 bar/s | 148 | 1.3 |

| 50 bar and 50 bar/s | 127 | 0.9 |

| 50 bar and 0.05 bar/s | 117 | 0.8 |

| Parameters | SBET, m2/g | P, % | Pmicro-CT, % (2–2100 µm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 100 bar and 0.05 bar/s (comparison sample) | 148 | 95 ± 2% | 6.32 ± 2% |

| Low process temperature (5 °C) | 112 | 95 ± 2% | 16.48 ± 2% |

| Pulsed pressure regime | 107 | 95 ± 2% | 20.64 ± 2% |

| Adding surfactant | 107 | 95 ± 2% | 20.93 ± 2% |

| Parameter | Mechanism | Macroporous Structure | Mesoporous Structure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pressure (50 → 100 bar) | ↑ CO2 solubility → ↓ pH → ↑ Ca2+ release → ↑ network stiffness at the moment of depressurization; ↑ supersaturation | Slow depressurization: pores (200–500 µm) with narrow size distribution. Fast depressurization: ↑ coalescence, formation of large pores (>2100 µm) | At 100 bar and slow depressurization: narrow distribution (20–35 nm). At fast depressurization: broader distribution (30–60 nm) |

| Depressurization rate (50 → 0.05 bar/s) | ↑ depressurization time → ↑ De, ↓ Pe (quasi-equilibrium depressurization, ↓ coalescence) | Narrower pore size distribution and ↓ mean diameter | Narrow mesopore size distribution combined with high surface area |

| Temperature (25 → 5 °C) | ↑ CO2 solubility; ↑ viscoelastic properties and relaxation time; ↓ diffusion coefficient | More homogeneous porous structure | Shift of distribution peak toward smaller diameters (12–25 nm) |

| Pulsed pressure variation | Repeated ΔP peaks: local ↑ Pe, directed flows and stress fields | Local coalescence, pores 100–300 µm; formation of large pores (>2100 µm) | No significant effect on mesostructure |

| Surfactant addition | ↓ interfacial tension → ↓ critical radius; stabilization of thin walls | Fine macroporous structure (100–300 µm) with peripheral coalescence | Shift of distribution peak toward smaller diameters (12–25 nm) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Menshutina, N.; Golubev, E.; Abramov, A.; Tsygankov, P. CO2-Induced Foaming and Gelation for the Fabrication of Macroporous Alginate Aerogel Scaffolds. Gels 2026, 12, 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010017

Menshutina N, Golubev E, Abramov A, Tsygankov P. CO2-Induced Foaming and Gelation for the Fabrication of Macroporous Alginate Aerogel Scaffolds. Gels. 2026; 12(1):17. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010017

Chicago/Turabian StyleMenshutina, Natalia, Eldar Golubev, Andrey Abramov, and Pavel Tsygankov. 2026. "CO2-Induced Foaming and Gelation for the Fabrication of Macroporous Alginate Aerogel Scaffolds" Gels 12, no. 1: 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010017

APA StyleMenshutina, N., Golubev, E., Abramov, A., & Tsygankov, P. (2026). CO2-Induced Foaming and Gelation for the Fabrication of Macroporous Alginate Aerogel Scaffolds. Gels, 12(1), 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010017