Design and In Vitro Evaluation of Cross-Linked Poly(HEMA)-Pectin Nano-Composites for Targeted Delivery of Potassium Channel Blockers in Cancer Therapy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Characterization of HPN, Dof-HPN, and Azi-HPN

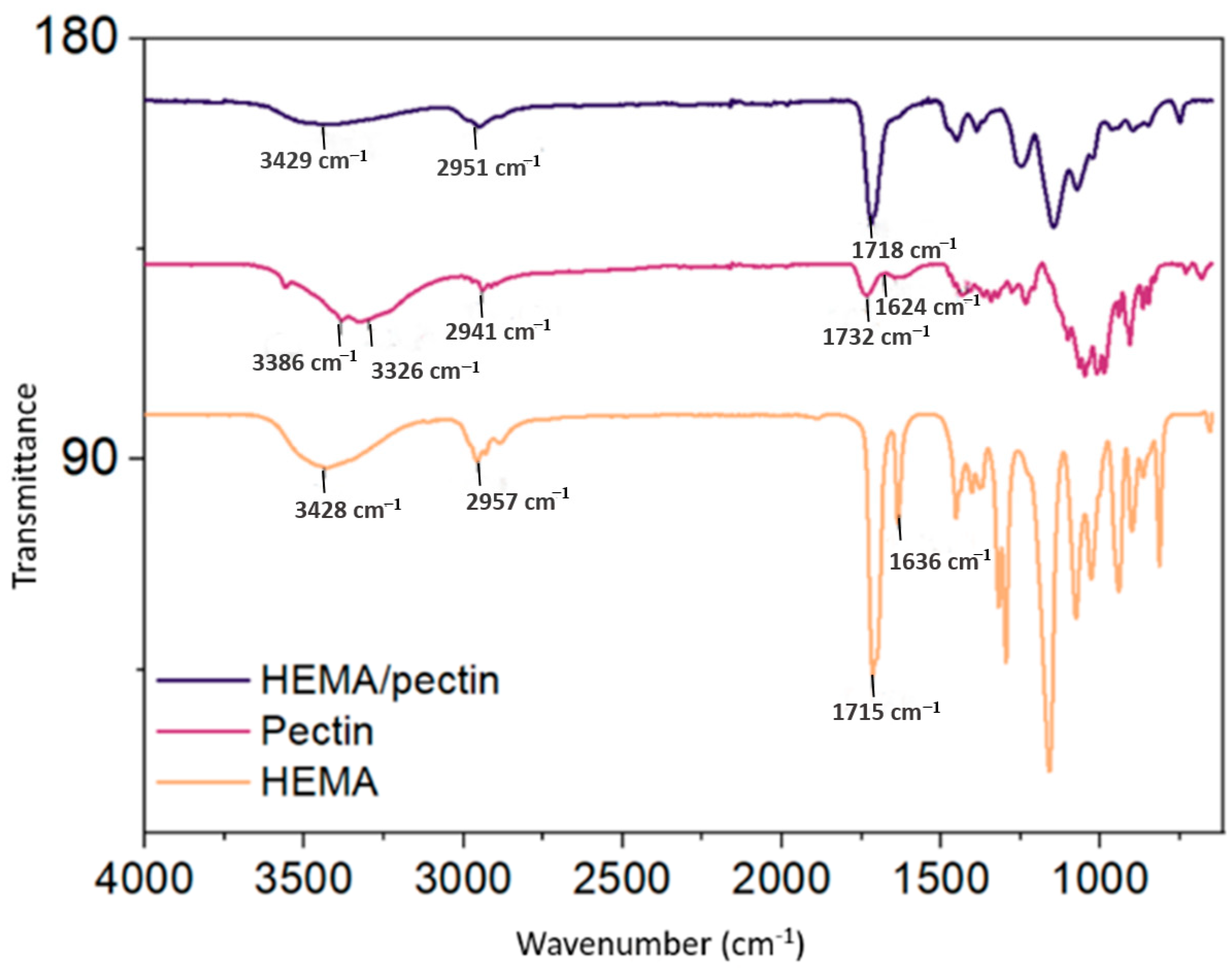

2.2. FTIR Analysis of HPN

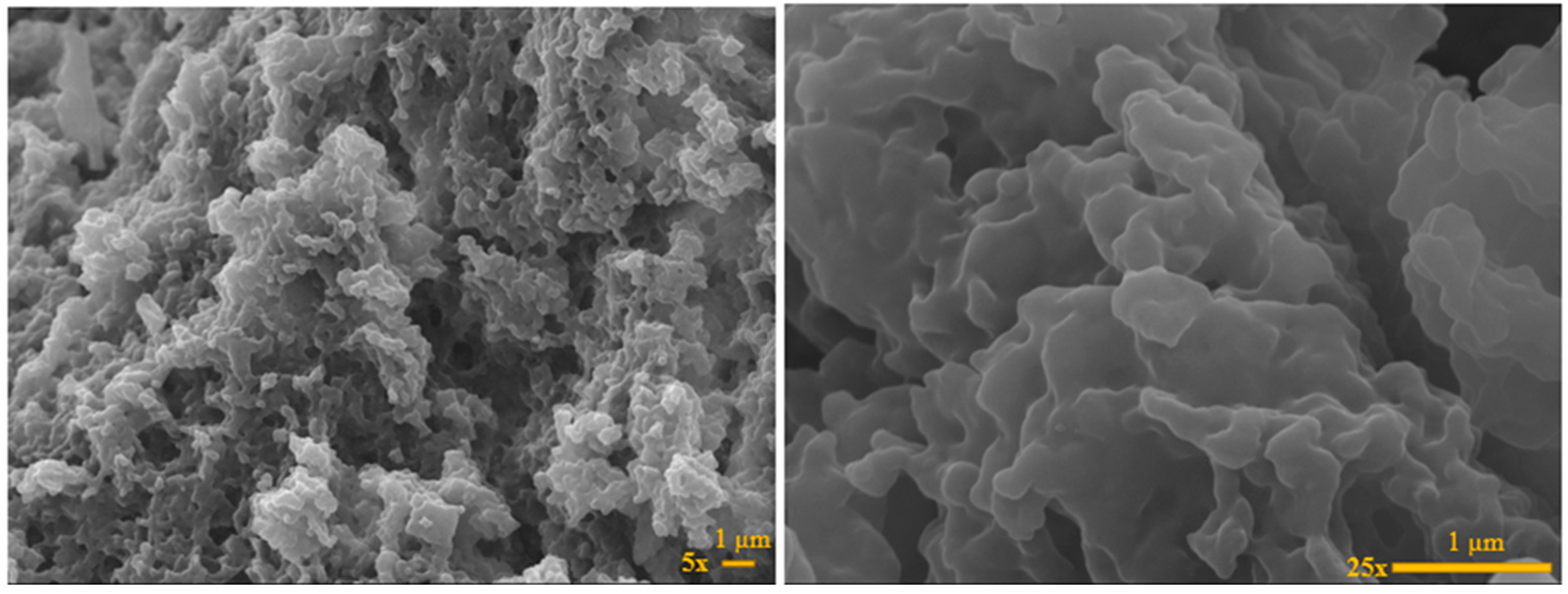

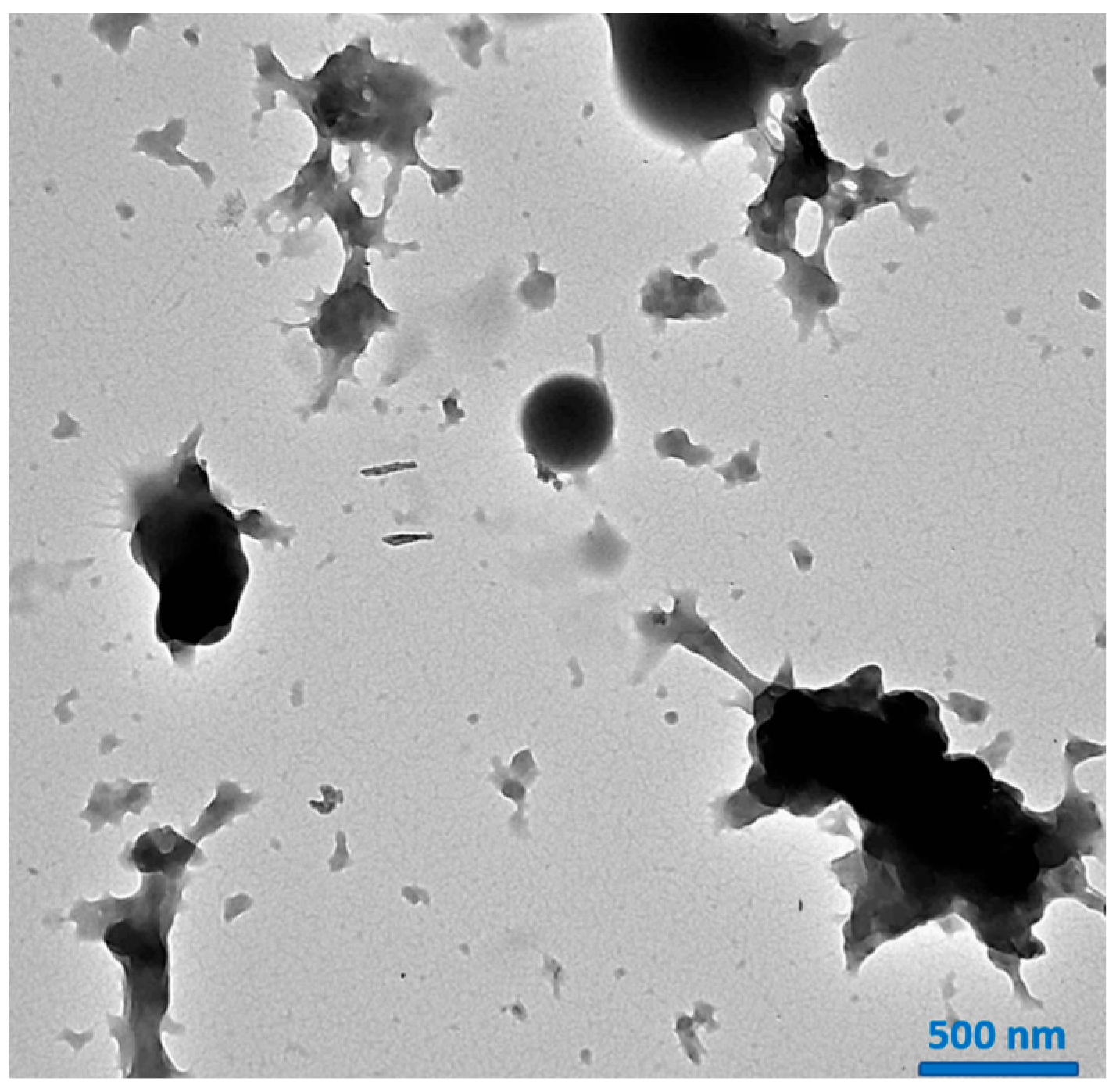

2.3. SEM and TEM Analysis of HPN

2.4. Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) Studies of HPN, Dof-HPN, and Azi-HPN

2.5. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) and Brunauer-Emmett Teller (BET) Analysis

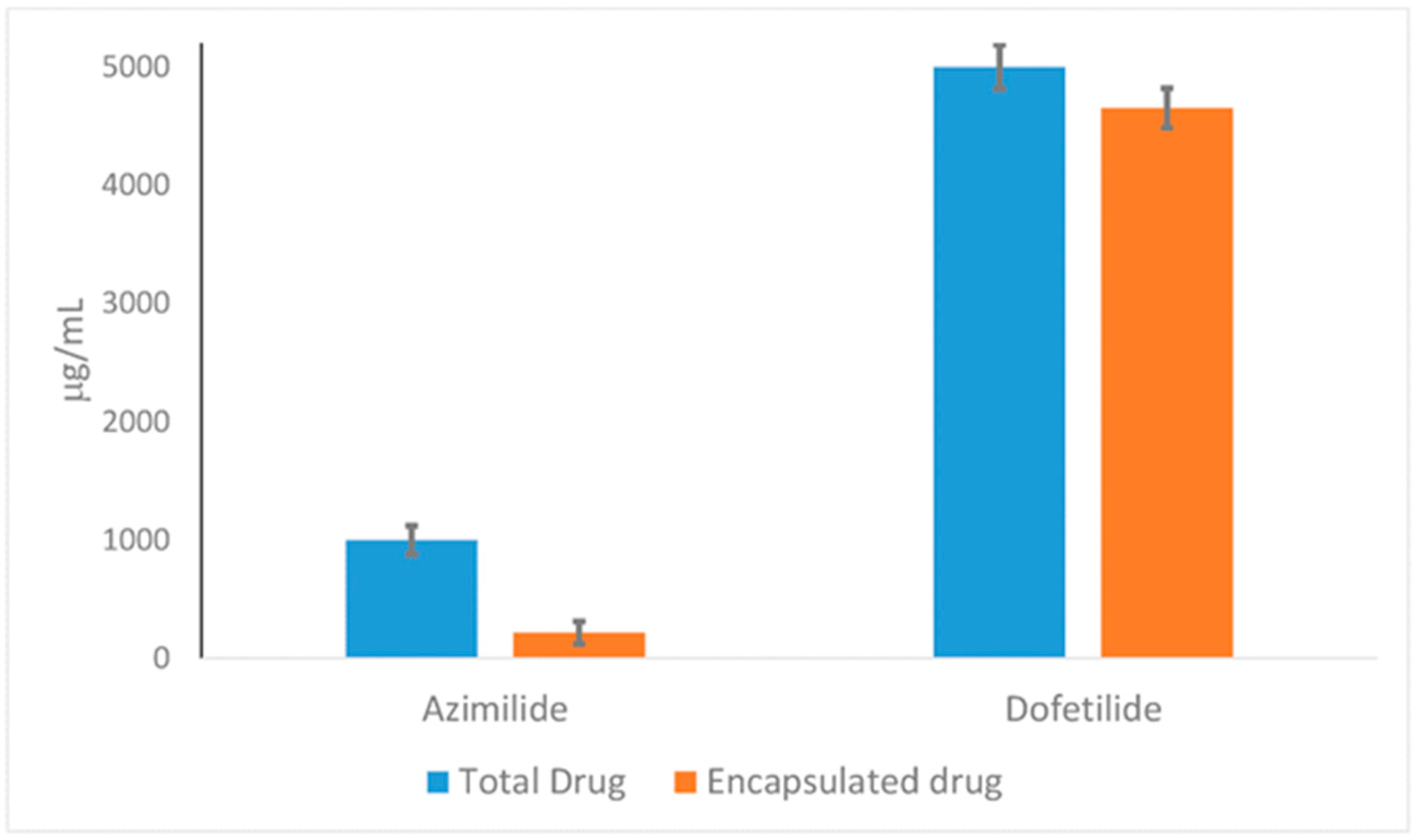

2.6. EE% and DL% Capacity of HPN Against Dof and Azi

2.7. Drug Release and Release Kinetic Studies of Dof-HPN and Azi-HPN

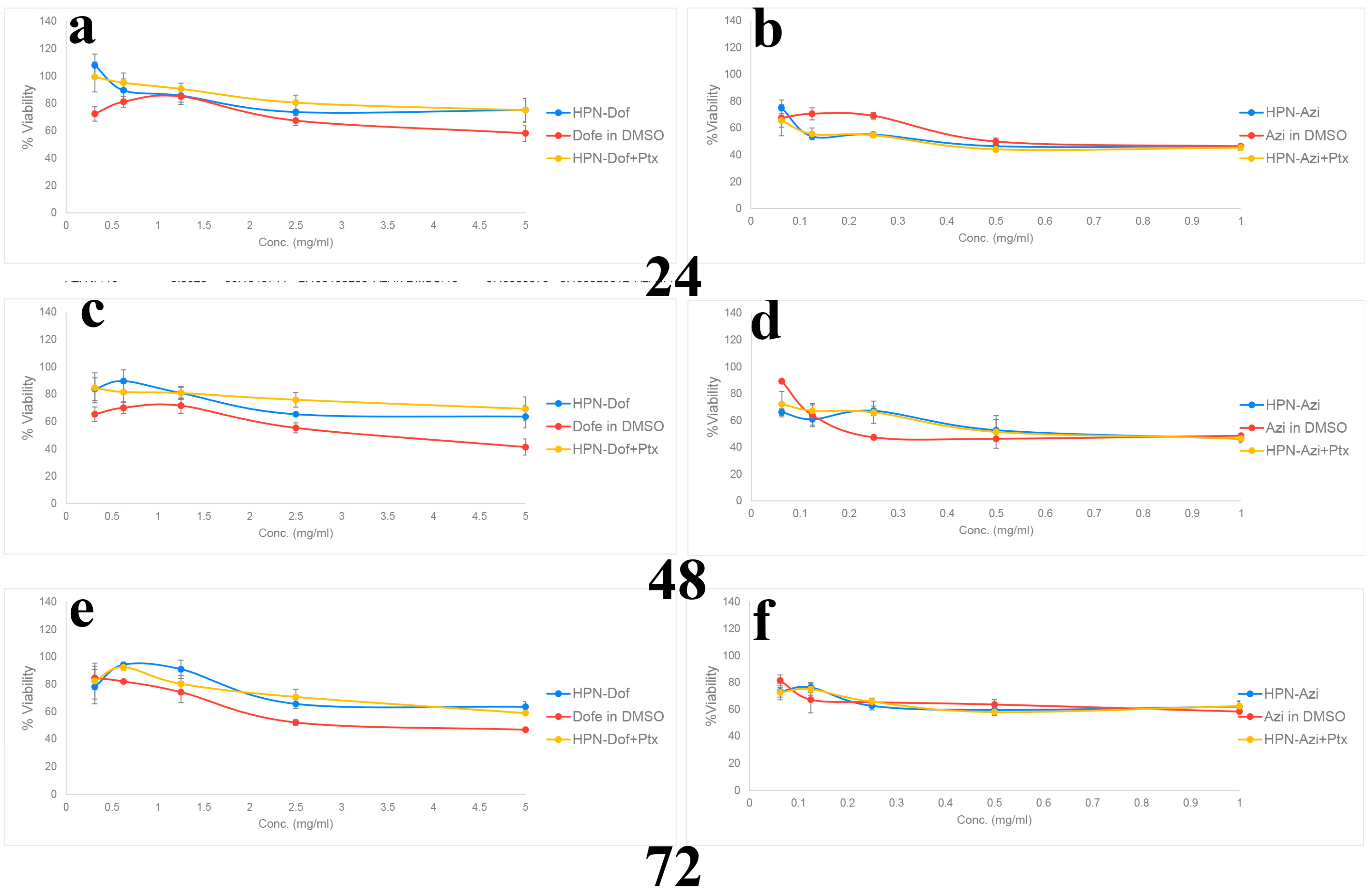

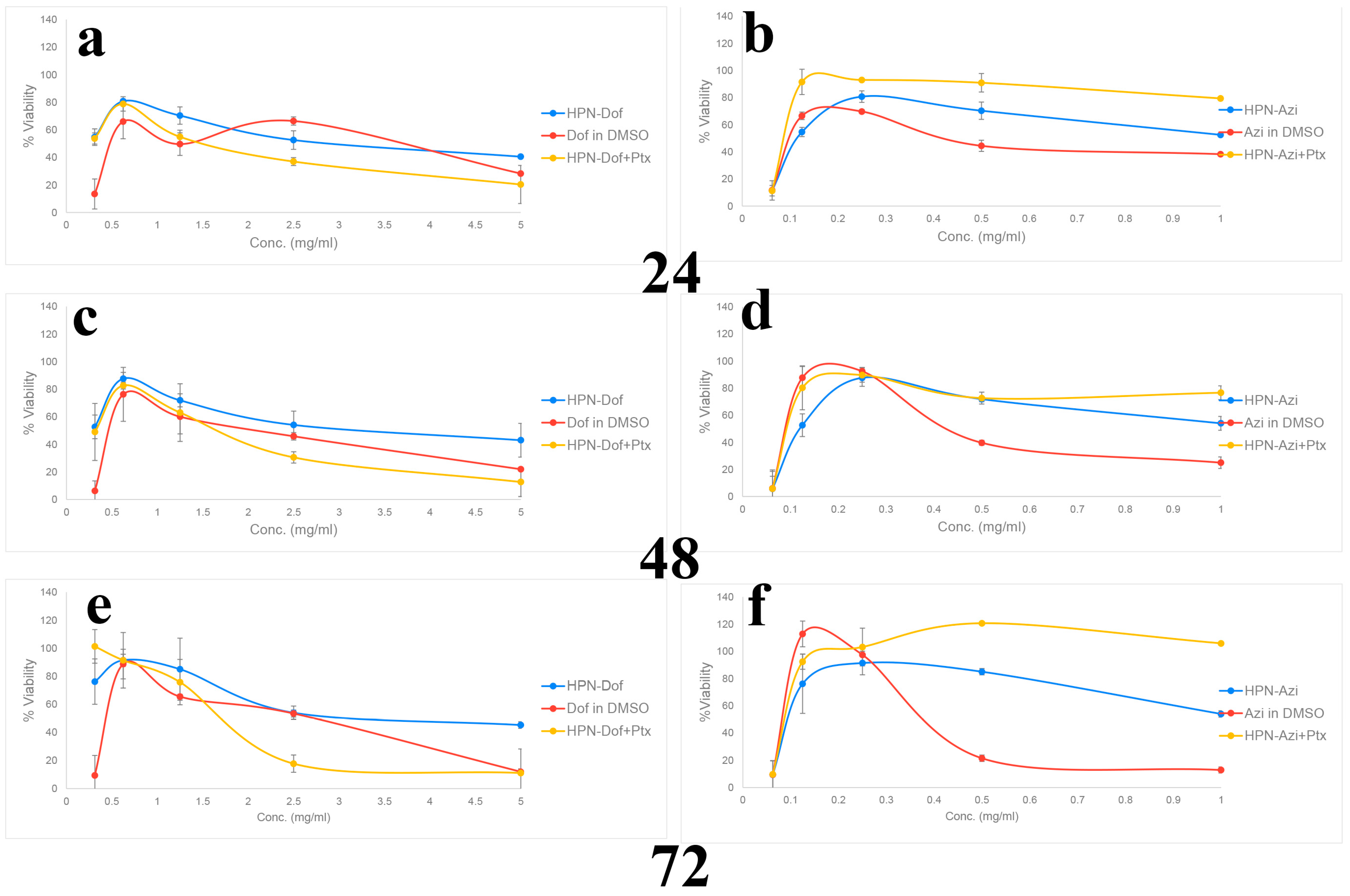

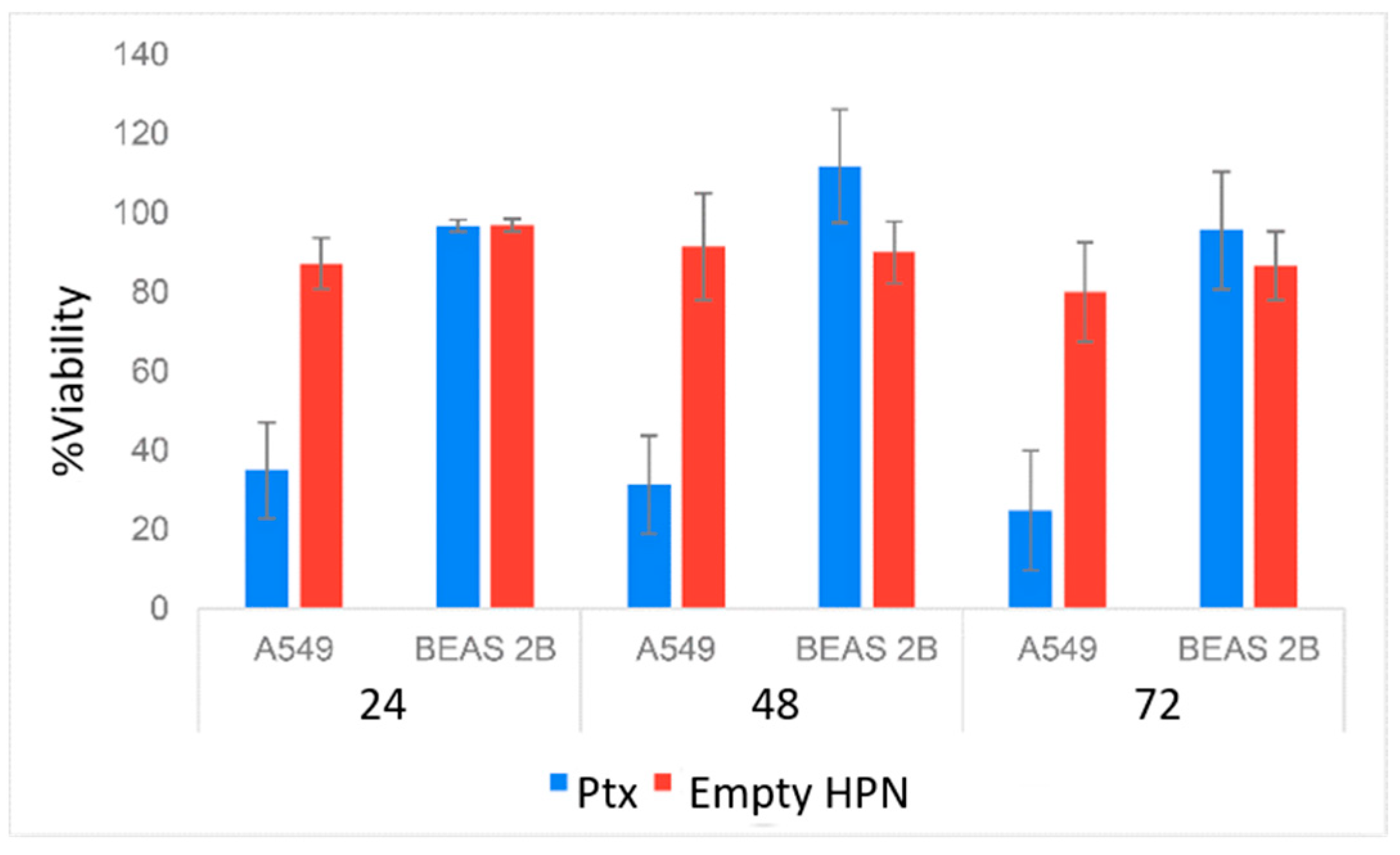

2.8. In Vitro Cytotoxicity and Anticancer Efficacy of Dof-HPN and Azi-HPN

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Methods

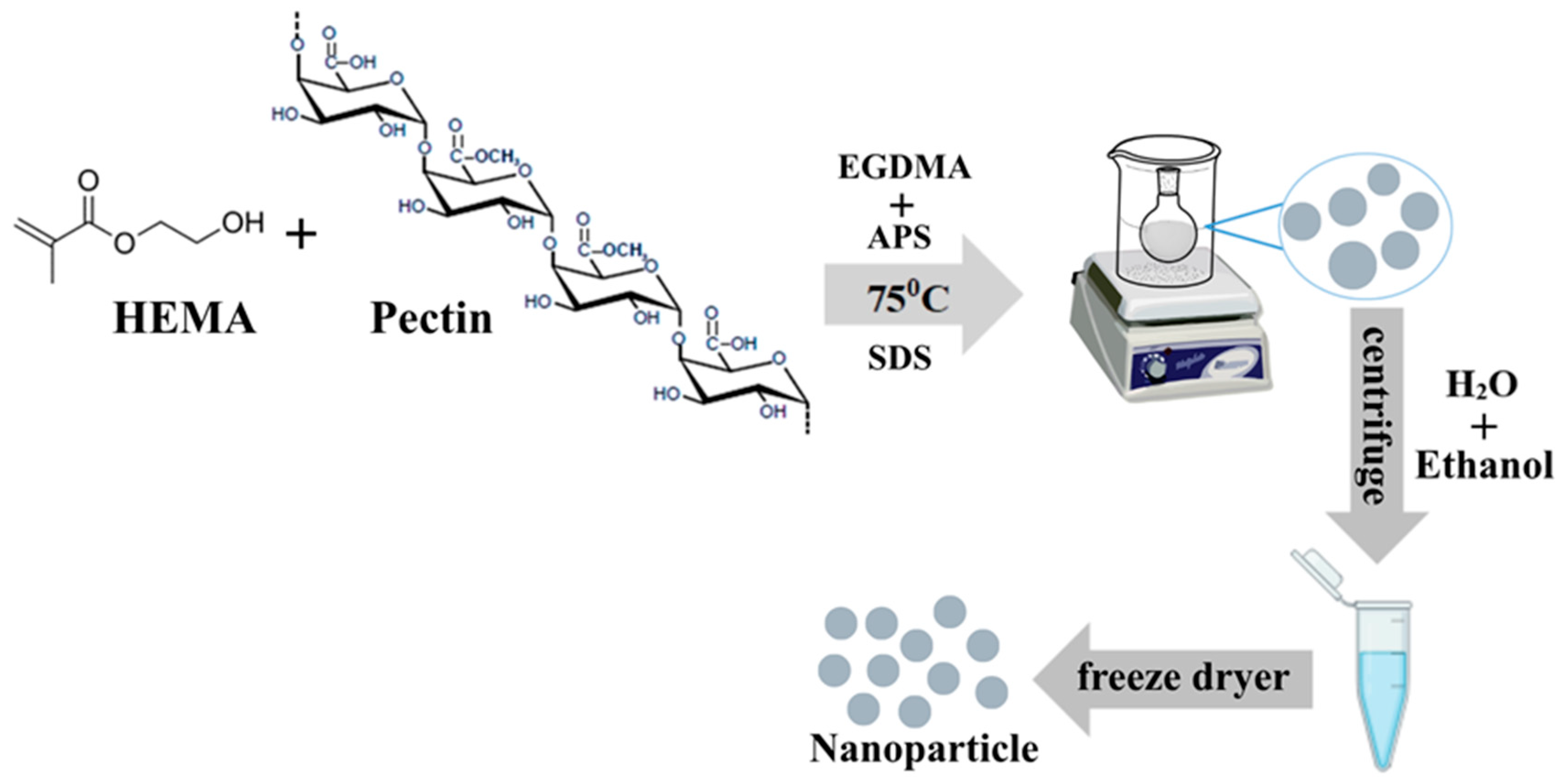

4.2.1. Synthesis of HEMA/Pectin Nanoparticle (HPN)

4.2.2. Characterization of Nanoparticles (NPs)

4.2.3. Drug Loading to HPN

4.2.4. Quantitative Measurement of Dof and Azi Using HPLC and Method Validation

4.2.5. Drug Release and Release Kinetic Studies of Dof-HPN and Azi-HPN

4.2.6. Encapsulation Efficiency (EE%) and Drug Loading (DL%) Capacity

4.2.7. In Vitro Cytotoxicity and Anticancer Efficacy of Dof-HPN and Azi-HPN

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| A549 | Human lung adenocarcinoma cell line |

| Azi | Azimilide |

| BEAS-2B | Human bronchial epithelial cell line |

| BET | Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (surface area analysis) |

| DLS | Dynamic Light Scattering |

| DL% | Drug Loading (percentage) |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| Dof | Dofetilide |

| EPR | Enhanced Permeability and Retention (effect) |

| EE% | Encapsulation Efficiency (percentage) |

| FTIR | Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| HEMA | 2-Hydroxyethyl methacrylate |

| HPN | HEMA–Pectin Nanoparticles |

| hERG/IKr | Human ether-à-go-go–related gene/rapid delayed rectifier K+ current |

| IKs | Slow delayed rectifier K+ current |

| K+ | Potassium ion |

| MTT | 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-Diphenyltetrazolium Bromide assay |

| NP | Nanoparticle |

| PDI | Polydispersity Index |

| Ptx | Paclitaxel |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| TEM | Transmission Electron Microscopy |

References

- Pardo, L.A.; Contreras-Jurado, C.; Zientkowska, M.; Alves, F.; Stühmer, W. Role of voltage-gated potassium channels in cancer. J. Membr. Biol. 2005, 205, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Jan, L.Y. Targeting potassium channels in cancer. J. Cell Biol. 2014, 206, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felipe, A.; Vicente, R.; Villalonga, N.; Roura-Ferrer, M.; Martínez-Mármol, R.; Solé, L.; Ferreres, J.C.; Condom, E. Potassium channels: New targets in cancer therapy. Cancer Detect. Prev. 2006, 30, 375–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zúñiga, L.; Cayo, A.; González, W.; Vilos, C.; Zúñiga, R. Potassium channels as a target for cancer therapy: Current perspectives. OncoTargets Ther. 2022, 15, 783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stortelers, C.; Pinto-Espinoza, C.; Van Hoorick, D.; Koch-Nolte, F. Modulating ion channel function with antibodies and nanobodies. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2018, 52, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Yang, J.; Li, X.; Liang, T.; Nie, C.; Xie, F.; Liu, K.; Peng, X.; Xie, J. Carbon nanoparticles enhance potassium uptake via upregulating potassium channel expression and imitating biological ion channels in BY-2 cells. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2020, 18, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Bu, W.; Ding, H.; Li, Q.; Wang, D.; Bi, H.; Guo, D. Cytotoxic effect of zinc oxide nanoparticles on murine photoreceptor cells via potassium channel block and Na+/K+-ATP ase inhibition. Cell Prolif. 2017, 50, e12339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J. The enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect:The significance of the concept and methods to enhance its application. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuperkar, K.; Atanase, L.I.; Bahadur, A.; Crivei, I.C.; Bahadur, P. Degradable polymeric bio (nano) materials and their biomedical applications: A comprehensive overview and recent updates. Polymers 2024, 16, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.K.; Lee, D.I.; Park, J.M. Biopolymer-based microgels/nanogels for drug delivery applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2009, 34, 1261–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahiner, N.; Godbey, W.; McPherson, G.L.; John, V.T. Microgel, nanogel and hydrogel–hydrogel semi-IPN composites for biomedical applications: Synthesis and characterization. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2006, 284, 1121–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakan, B.; Gülcemal, S.; Akgöl, S.; Hoet, P.H.; Yavaşoğlu, N.Ü.K. Synthesis, characterization and toxicity assessment of a new polymeric nanoparticle, l-glutamic acid-g-p (HEMA). Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2020, 315, 108870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouhan, R.; Bajpai, A. Real time in vitro studies of doxorubicin release from PHEMA nanoparticles. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2009, 7, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, M. Synthesis of starch-g-poly (acrylic acid-co-2-hydroxy ethyl methacrylate) as a potential pH-sensitive hydrogel-based drug delivery system. Turk. J. Chem. 2011, 35, 723–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, R.C.; Yang, H. Hydrogel-based ocular drug delivery systems: Emerging fabrication strategies, applications, and bench-to-bedside manufacturing considerations. J. Control. Release 2019, 306, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozay, O. Synthesis and characterization of novel pH-responsive poly (2-hydroxylethyl methacrylate-co-N-allylsuccinamic acid) hydrogels for drug delivery. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2014, 131, 39660. [Google Scholar]

- Moghadam, M.N.; Pioletti, D.P. Biodegradable HEMA-based hydrogels with enhanced mechanical properties. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B Appl. Biomater. 2016, 104, 1161–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, C.; Martello, F.; Erratico, S.; Tocchio, A.; Belicchi, M.; Lenardi, C.; Torrente, Y. P (NIPAAM–co-HEMA) thermoresponsive hydrogels: An alternative approach for muscle cell sheet engineering. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2017, 11, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, T.; Yuan, P.; Tian, R.; Hu, W.; Tang, Y.; Jia, Y.; Zhang, L. Encapsulation of honokiol into self-assembled pectin nanoparticles for drug delivery to HepG2 cells. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 133, 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Krivorotova, T.; Cirkovas, A.; Maciulyte, S.; Staneviciene, R.; Budriene, S.; Serviene, E.; Sereikaite, J. Nisin-loaded pectin nanoparticles for food preservation. Food Hydrocoll. 2016, 54, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.; Lim, L.Y. Insulin-loaded calcium pectinate nanoparticles: Effects of pectin molecular weight and formulation pH. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2004, 30, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.S.; Ji, S.M.; Park, M.J.; Suneetha, M.; Uthappa, U.T. Pectin based hydrogels for drug delivery applications: A mini review. Gels 2022, 8, 834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mena-Giraldo, P.; Pérez-Buitrago, S.; Londoño-Berrío, M.; Ortiz-Trujillo, I.C.; Hoyos-Palacio, L.M.; Orozco, J. Photosensitive nanocarriers for specific delivery of cargo into cells. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balıbey, F.B.; Bahadori, F.; Ergin Kizilcay, G.; Tekin, A.; Kanimdan, E.; Kocyigit, A. Optimization of PLGA-DSPE hybrid nano-micelles with enhanced hydrophobic capacity for curcumin delivery. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 2023, 28, 843–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şeref, E.; Ilgin, P.; Ozay, O.; Ozay, H. A new candidate for wound dressing materials: S-IPN hydrogel-based highly elastic and pH-sensitive drug delivery system containing pectin and vinyl phosphonic acid. Eur. Polym. J. 2024, 207, 112824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senol, S.; Akyol, E. Synthesis and characterization of hydrogels based on poly (2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate) for drug delivery under UV irradiation. J. Mater. Sci. 2018, 53, 14953–14963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozay, O.; Ilgin, P.; Ozay, H.; Gungor, Z.; Yilmaz, B.; Kıvanç, M.R. The preparation of various shapes and porosities of hydroxyethyl starch/p (HEMA-co-NVP) IPN hydrogels as programmable carrier for drug delivery. J. Macromol. Sci. Part A 2020, 57, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabry, R.; Sayed, A.; El-Sayed, I.E.; Mahmoud, G.A. Optimizing pectin-based biofilm properties for food packaging via E-beam irradiation. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2025, 229, 112474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour Mohamed, T.; Sayed Ali, A.; Mahmoud, G.A. Preparation and Characterization of Pectin/HEMA/ZrO2 Composite Via Gamma Irradiation: Antimicrobial and Anti-Inflammatory Activities. ChemistrySelect 2025, 10, e02158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waje, S.; Meshram, M.; Chaudhary, V.; Pandey, R.; Mahanawar, P.; Thorat, B. Drying and shrinkage of polymer gels. Braz. J. Chem. Eng. 2005, 22, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, S. Development of Hierarchical Magnetic Nanocomposite Materials for Biomedical Applications. Ph.D. Thesis, Dublin City University, Dublin, Ireland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Stetefeld, J.; McKenna, S.A.; Patel, T.R. Dynamic light scattering: A practical guide and applications in biomedical sciences. Biophys. Rev. 2016, 8, 409–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, A.; Sharma, D.; Singh, B. Assessment of physicochemical properties of polysaccharide derived mucoadhesive hydrogels to design tunable drug delivery carriers. Med. Nov. Technol. Devices 2025, 26, 100360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sing, K.S.W. Reporting physisorption data for gas/solid systems with special reference to the determination of surface area and porosity (Recommendations 1984). Pure Appl. Chem. 1985, 57, 603–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ru, Q.; Li, W.-l.; Xiong, Q.; Chen, L.; Tian, X.; Li, C.-Y. Voltage-gated potassium channel blocker 4-aminopyridine induces glioma cell apoptosis by reducing expression of microRNA-10b-5p. Mol. Biol. Cell 2018, 29, 1125–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atlıbatur, R.; Bahadori, F.; Kizilcay, G.E.; Ide, S.; Gürsel, Y. Preparation and characterization of glyceryl dibehenate and glyceryl monostearate-based lyotropic liquid crystal nanoparticles as carriers for hydrophobic drugs. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2023, 87, 104821. [Google Scholar]

- Daryan, S.H.; Javadpour, J.; Khavandi, A. Synthesis and drug release study of ciprofloxacin loaded hierarchical hydroxyapatite mesoporous microspheres. Results Chem. 2025, 14, 102123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredenberg, S.; Wahlgren, M.; Reslow, M.; Axelsson, A. The mechanisms of drug release in poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid)-based drug delivery systems—A review. Int. J. Pharm. 2011, 415, 34–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannunah, A.; Cavanagh, R.; Shubber, S.; Vllasaliu, D.; Stolnik, S. Difference in endocytosis pathways used by differentiated versus nondifferentiated epithelial caco-2 cells to internalize nanosized particles. Mol. Pharm. 2024, 21, 3603–3612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannunah, A.M.; Vllasaliu, D.; Lord, J.; Stolnik, S. Mechanisms of nanoparticle internalization and transport across an intestinal epithelial cell model: Effect of size and surface charge. Mol. Pharm. 2014, 11, 4363–4373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattson, M.P. Hormesis defined. Ageing Res. Rev. 2008, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danaei, M.; Dehghankhold, M.; Ataei, S.; Hasanzadeh Davarani, F.; Javanmard, R.; Dokhani, A.; Khorasani, S.; Mozafari, Y.M. Impact of particle size and polydispersity index on the clinical applications of lipidic nanocarrier systems. Pharmaceutics 2018, 10, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, A.R.; Majdoub, H.; Jabrail, F.H. Effects of surface morphology and type of cross-linking of chitosan-pectin microspheres on their degree of swelling and favipiravir release behavior. Polymers 2023, 15, 3173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Mooney, D.J. Designing hydrogels for controlled drug delivery. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2016, 1, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajaz, N.; Khalid, I.; Minhas, M.U.; Barkat, K.; Khan, I.U.; Syed, H.K.; Asghar, S.; Munir, R.; Aslam, F. Pectin-based hydrogels with adjustable properties for controlled delivery of nifedipine: Development and optimization. Polym. Bull. 2020, 77, 6063–6083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokhale, A. Achieving zero-order release kinetics using multi-step diffusion-based drug delivery. Pharm. Technol. Eur. 2014, 26, 38–42. [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese, E.J.; Baldwin, L.A. Hormesis: The dose-response revolution. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2003, 43, 175–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agathokleous, E.; Calabrese, E.J. Hormesis: A general biological principle. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2022, 35, 547–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Opstal, J.M.; Leunissen, J.D.; Wellens, H.J.; Vos, M.A. Azimilide and dofetilide produce similar electrophysiological and proarrhythmic effects in a canine model of Torsade de Pointes arrhythmias. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2001, 412, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gintant, G.A. Azimilide causes reverse rate-dependent block while reducing both components of delayed-rectifier current in canine ventricular myocytes. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1998, 31, 945–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takács, J.; Iost, N.; Lengyel, C.; Virág, L.; Nesic, M.; Varró, A.; Papp, J.G. Multiple cellular electrophysiological effects of azimilide in canine cardiac preparations. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2003, 470, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ágoston, M.; Kohajda, Z.; Virág, L.; Baláti, B.; Nagy, N.; Lengyel, C.; Bitay, M.; Bogáts, G.; Vereckei, A.; Papp, J.G. A comparative study of the rapid (IKr) and slow (IKs) delayed rectifier potassium currents in undiseased human, dog, rabbit, and guinea pig cardiac ventricular preparations. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- YAO, J.A.; TSENG, G.N. Azimilide (NE-10064) Can Prolong or Shorten the Action Potential Duration in Canine Ventricular Myocytes: Dependence on Blockade of K, Ca, and Na Channels. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 1997, 8, 184–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahiner, N.; Ozay, O. Responsive tunable colloidal soft materials based on p(4-VP) for potential biomedical and environmental applications. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2011, 378, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guideline, I.H.T. Validation of analytical procedures: Text and methodology. Q2 (R1). ICH Harmon. 2005, 1, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Vatansever, O.; Bahadori, F.; Bulut, S.; Eroglu, M.S. Coating with cationic inulin enhances the drug release profile and in vitro anticancer activity of lecithin-based nano drug delivery systems. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 237, 123955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojsteršek, T.; Vrečer, F.; Hudovornik, G. Comparative fitting of mathematical models to carvedilol release profiles obtained from hypromellose matrix tablets. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, M.; Elasad, R.; Mestiri, S.; Jeya, S.S.P.; Al Ejeh, F.; AL-Muftah, M. GSK343 Potentiates the Response of Paclitaxel in Triple Negative Breast Cancer Cell Lines. Fortune J. Health Sci. 2025, 8, 582–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolosa, L.; Donato, M.T.; Gómez-Lechón, M.J. General cytotoxicity assessment by means of the MTT assay. In Protocols in In Vitro Hepatocyte Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 333–348. [Google Scholar]

| Size Distribution | Number | Volume | Intensity | PDI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPN | 220.0 ± 17.36 | 230.7 ± 22.76 | 227.9 ± 24.98 | 0.152 |

| Dof-HPN | 230.3 ± 19.34 | 240.1 ± 23.85 | 235.1 ± 25.01 | 0.181 |

| Azi-HPN | 228.0 ± 16.83 | 238.3 ± 20.55 | 232.1 ± 22.08 | 0.130 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Civir, G.O.; Bahadori, F.; Ozay, O.; Ergin Kızılçay, G.; Atesoglu, S.; Aldogan, E.H.; Celik, B. Design and In Vitro Evaluation of Cross-Linked Poly(HEMA)-Pectin Nano-Composites for Targeted Delivery of Potassium Channel Blockers in Cancer Therapy. Gels 2026, 12, 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010013

Civir GO, Bahadori F, Ozay O, Ergin Kızılçay G, Atesoglu S, Aldogan EH, Celik B. Design and In Vitro Evaluation of Cross-Linked Poly(HEMA)-Pectin Nano-Composites for Targeted Delivery of Potassium Channel Blockers in Cancer Therapy. Gels. 2026; 12(1):13. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010013

Chicago/Turabian StyleCivir, Gizem Ozkurnaz, Fatemeh Bahadori, Ozgur Ozay, Gamze Ergin Kızılçay, Seyma Atesoglu, Ebru Haciosmanoglu Aldogan, and Burak Celik. 2026. "Design and In Vitro Evaluation of Cross-Linked Poly(HEMA)-Pectin Nano-Composites for Targeted Delivery of Potassium Channel Blockers in Cancer Therapy" Gels 12, no. 1: 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010013

APA StyleCivir, G. O., Bahadori, F., Ozay, O., Ergin Kızılçay, G., Atesoglu, S., Aldogan, E. H., & Celik, B. (2026). Design and In Vitro Evaluation of Cross-Linked Poly(HEMA)-Pectin Nano-Composites for Targeted Delivery of Potassium Channel Blockers in Cancer Therapy. Gels, 12(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010013