Texture Properties and Chewing of κ-Carrageenan–Konjac Gum–Milk Hydrogels Modified with Carrot Callus Cells

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Microstructure of Hydrogels

2.2. FTIR Spectroscopy of Hydrogels

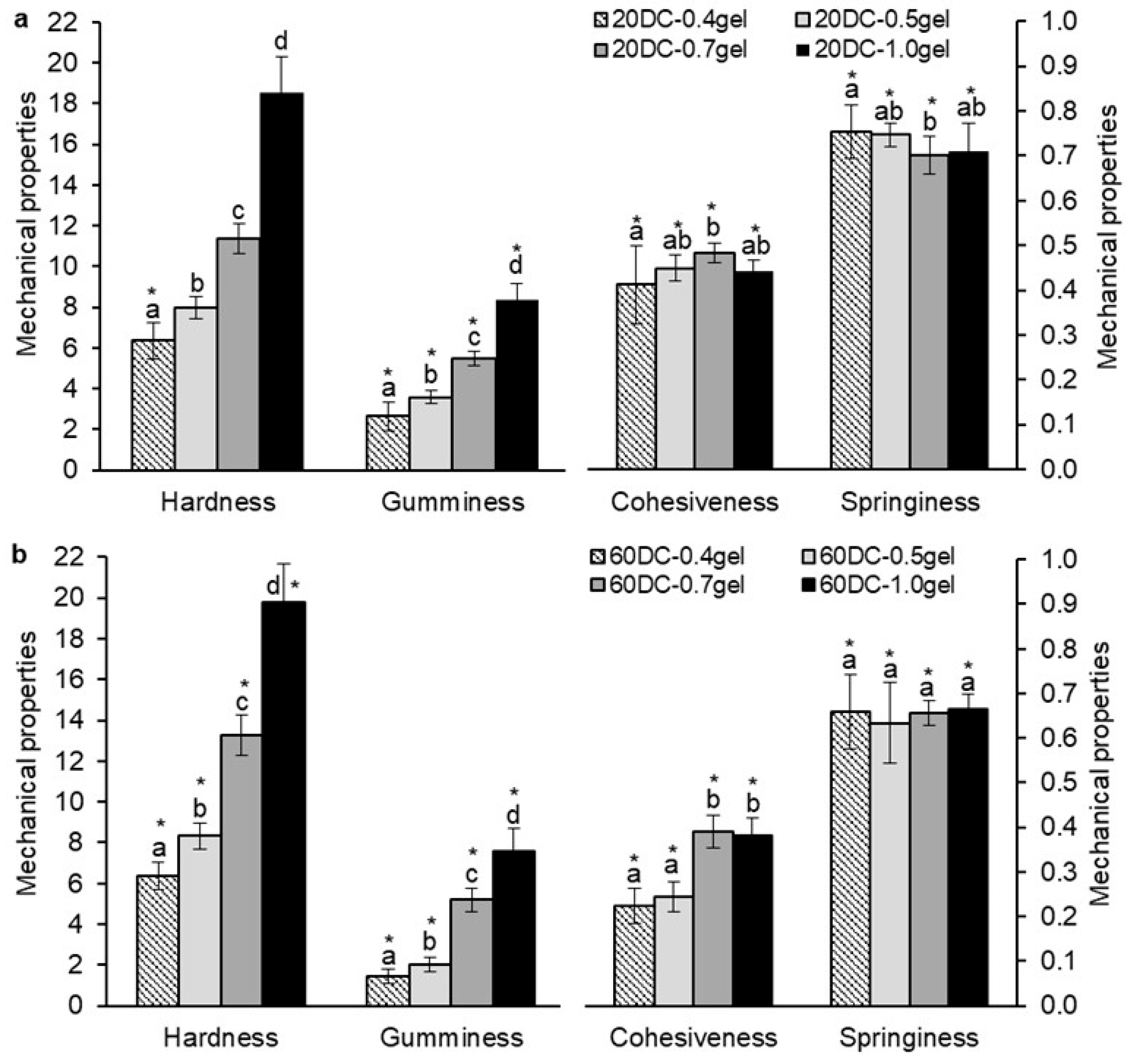

2.3. Mechanical Properties of κ-Carrageenan–Konjac Gum–Milk Hydrogels

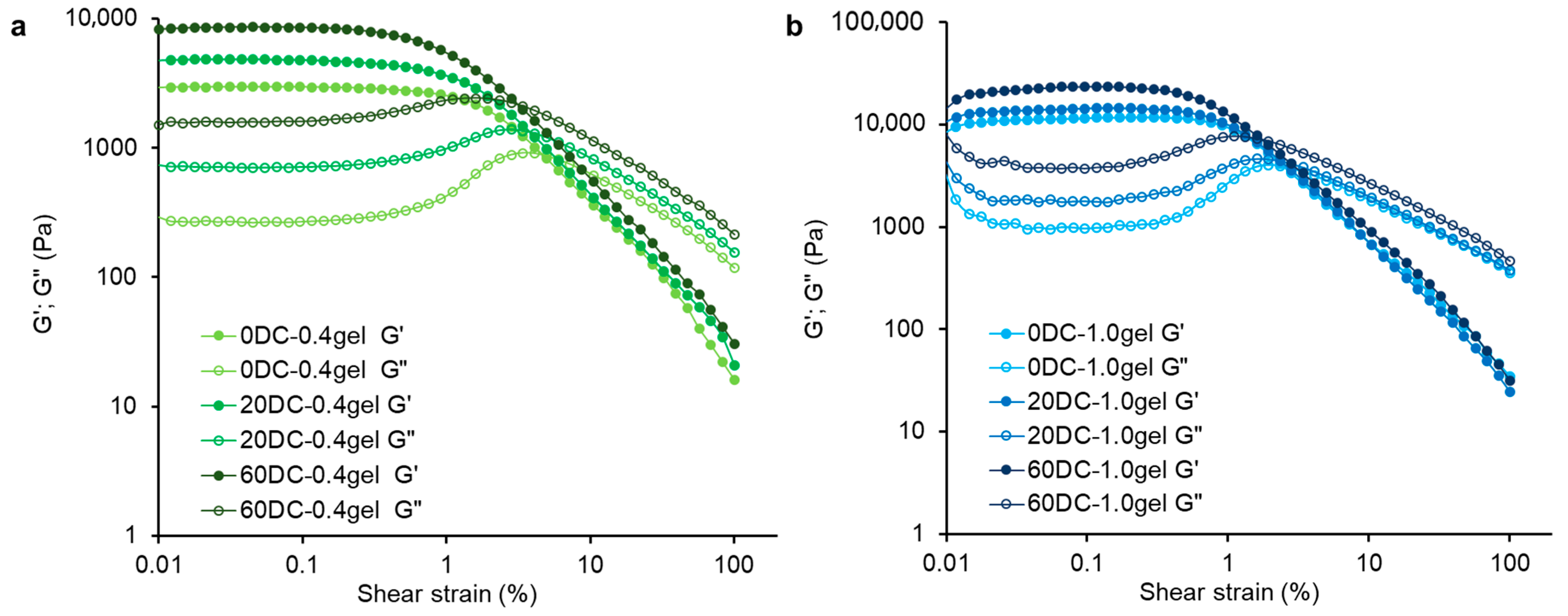

2.4. Rheological Properties of Hydrogels

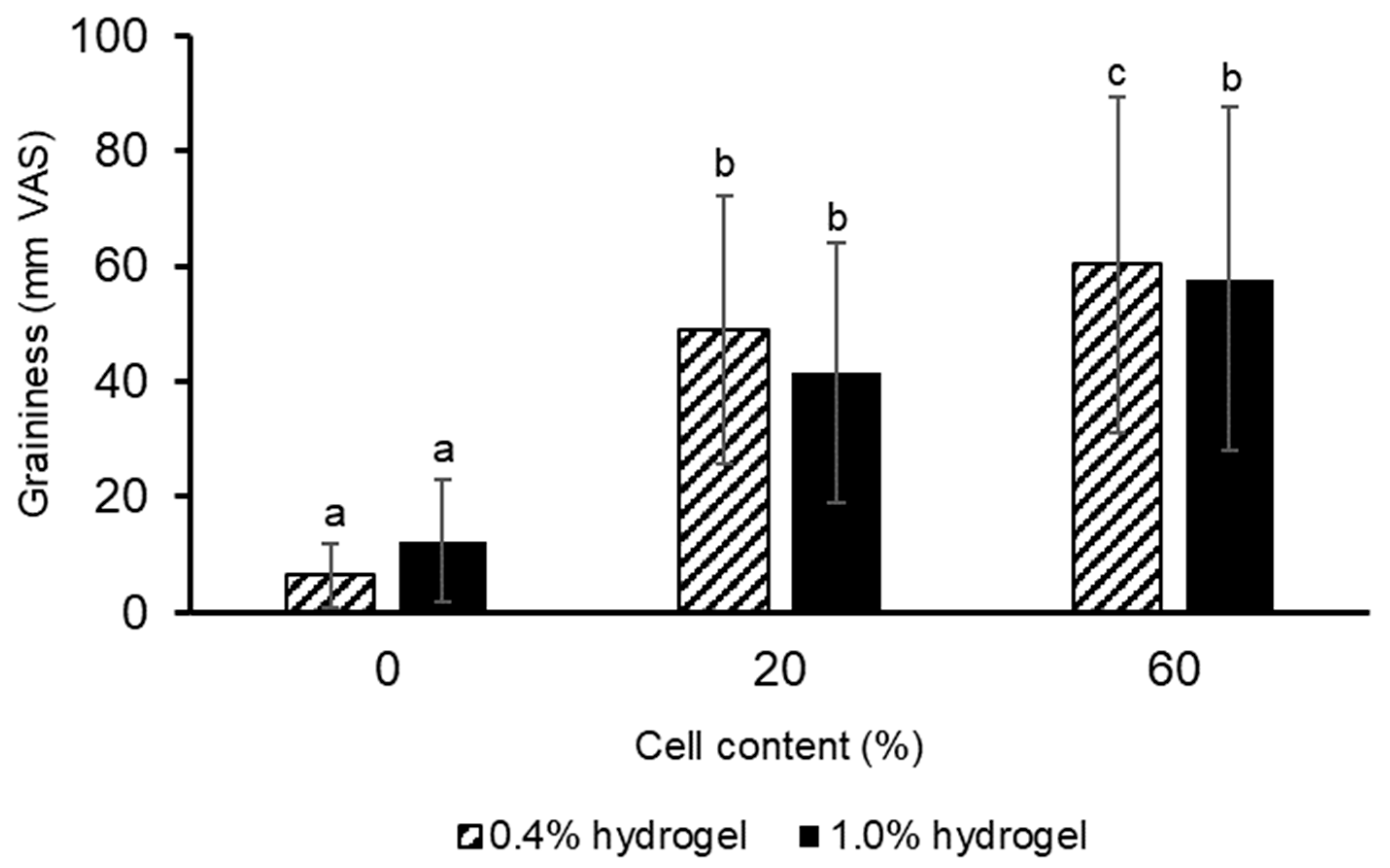

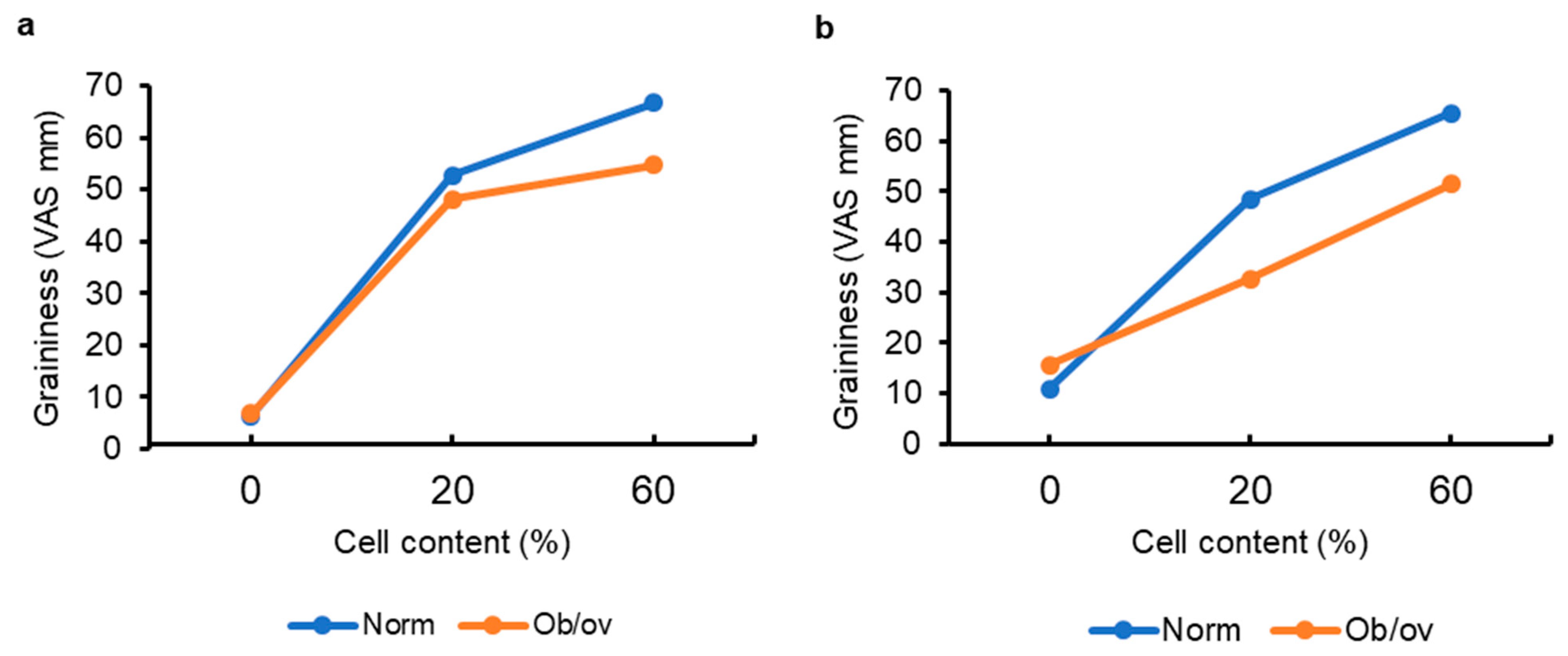

2.5. Sensory Properties and Chewing of Hydrogels

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Callus Culture of Daucus Carota

4.3. Preparation of κ-Carrageenan–Konjac Gum–Milk Hydrogels Encapsulated with Callus Cells

4.4. Scanning Electron Microscopy

4.5. Porosity Measurement

4.6. The Moisture Content

4.7. FTIR Spectroscopy

4.8. Mechanical Properties of Hydrogels

4.9. Rheological Properties

4.10. Sensory Evaluation and EMG Activity

4.11. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pascuta, M.S.; Varvara, R.-A.; Teleky, B.-E.; Szabo, K.; Plamada, D.; Nemeş, S.-A.; Mitrea, L.; Martău, G.A.; Ciont, C.; Călinoiu, L.F.; et al. Polysaccharide-based edible gels as functional ingredients: Characterization, applicability, and human health benefits. Gels 2022, 8, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, A.; Dar, A.H.; Pandey, V.K.; Shams, R.; Khan, S.; Panesar, P.S.; Kennedy, J.F.; Fayaz, U.; Khan, S.A. Recent insights into polysaccharide-based hydrogels and their potential applications in food sector: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 213, 987–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordlund, E.; Lille, M.; Silventoinen, P.; Nygren, H.; Seppänen-Laakso, T.; Mikkelson, A.; Aura, A.-M.; Heiniö, R.-L.; Nohynek, L.; Puupponen-Pimiä, R.; et al. Plant cells as food—A concept taking shape. Food Res. Int. 2018, 107, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidel, J.; Ahlfeld, T.; Adolph, M.; Kümmritz, S.; Steingroewer, J.; Krujatz, F.; Bley, T.; Gelinsky, M.; Lode, A. Green bioprinting: Extrusion-based fabrication of plant cell-laden biopolymer hydrogel scaffolds. Biofabrication 2017, 9, 045011–045023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vancauwenberghe, V.; Baiye Mfortaw Mbong, V.; Vanstreels, E.; Verboven, P.; Lammertyn, J.; Nicolai, B. 3D printing of plant tissue for innovative food manufacturing: Encapsulation of alive plant cells into pectin based bio-ink. J. Food Eng. 2019, 263, 454–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.M.; Kim, H.W.; Park, H.J. Callus-based 3D printing for food exemplified with carrot tissues and its potential for innovative food production. J. Food Eng. 2020, 271, 109781–109788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, A.; Gemeda, H.B.; McNulty, M.J.; McDonald, K.A.; Nandi, S.; Knipe, J.M. Immobilization of transgenic plant cells towards bioprinting for production of a recombinant biodefense agent. Biotechnol. J. 2021, 16, 2100133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landerneau, S.; Lemarié, L.; Marquette, C.; Petiot, E. Green 3D bioprinting of plant cells: A new scope for 3D bioprinting. Bioprinting 2022, 27, e00216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belova, K.; Dushina, E.; Popov, S.; Zlobin, A.; Martinson, E.; Vityazev, F.; Litvinets, S. Enrichment of 3D-printed k-carrageenan food gel with callus tissue of narrow-leaved lupin Lupinus angustifolius. Gels 2023, 9, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dushina, E.; Popov, S.; Zlobin, A.; Martinson, E.; Paderin, N.; Vityazev, F.; Belova, K.; Litvinets, S. Effect of homogenized callus tissue on the rheological and mechanical properties of 3D-printed food. Gels 2024, 10, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günter, E.; Popeyko, O.; Vityazev, F.; Popov, S. Effect of callus cell immobilization on the textural and rheological properties, loading and releasing of grape seed extract from pectin hydrogels. Gels 2024, 10, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günter, E.; Popeyko, O.; Vityazev, F.; Zueva, N.; Velskaya, I.; Popov, S. Effect of carrot callus cells on the mechanical, rheological, and sensory properties of hydrogels based on xanthan and konjac gums. Gels 2024, 10, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günter, E.A.; Popeyko, O.V.; Shevchenko, O.G.; Vityazev, F.V. Modification of texture and in vitro digestion of pectin and κ-carrageenan food hydrogels with antioxidant properties using plant cells. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 316, 144682–144696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Li, P.; Yu, S.; Cui, Z.; Xu, T.; Ouyang, L. Optimizing extrusion-based 3D bioprinting of plant cells with enhanced resolution and cell viability. Biofabrication 2025, 17, 025008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günter, E.; Popeyko, O.; Popov, S. Ca-alginate hydrogel with immobilized callus cells as a new delivery system of grape seed extract. Gels 2023, 9, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Feng, Y.; Kong, B.; Xia, X.; Liu, M.; Chen, J.; Zhang, F.; Liu, Q. Textural and gel properties of frankfurters as influenced by various κ-carrageenan incorporation methods. Meat Sci. 2021, 176, 108483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peh, F.Z.W.; Zhao, L.; Chia, Y.Y.; Ng, C.K.Z.; Du, J. Texture improvement and in vitro digestion modulation of plant-based fish cake analogue by incorporating hydrocolloid blends. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2024, 8, 100775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ropciuc, S.; Ghinea, C.; Leahu, A.; Prisacaru, A.E.; Oroian, M.A.; Apostol, L.C.; Dranca, F. Development and characterization of new plant-based ice cream assortments using oleogels as fat source. Gels 2024, 10, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleton, K.M.; Newbury, A.; Almiron-Roig, E.; Yeomans, M.R.; Brunstrom, J.M.; de Graaf, K.; Geurts, L.; Kildegaard, H.; Vinoy, S. Sensory and physical characteristics of foods that impact food intake without affecting acceptability: Systematic review and meta-analyses. Obes. Rev. Off. J. Int. Assoc. Study Obes. 2021, 22, e13234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Manei, K.; Jia, L.; Al-Manei, K.K.; Ndanshau, E.L.; Grigoriadis, A.; Kumar, A. Food hardness modulates behavior, cognition, and brain activation: A systematic review of animal and human studies. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maji, K.; Mallick, S.; Basak, A.; Ghosh, S. Carotenoids as a nutraceutical for human health and disease prevention. In Dietary Supplements and Nutraceuticals; Mukherjee, B., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, M.-X.; Zhub, Y.-D.; Li, D.; Adhikari, B.; Wang, L.-J. Rheological, thermal and microstructural properties of casein/κ-carrageenan mixed systems. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 113, 108296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhou, D.; Guo, Q.; Liu, C. Textural and structural properties of a κ-carrageenan-konjac gum mixed gel: Effects of κ-carrageenan concentration, mixing ratio, sucrose and Ca2+ concentrations and its application in milk pudding. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2021, 101, 3021–3029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zia, K.M.; Tabasum, S.; Nasif, M.; Sultan, N.; Aslam, N.; Noreen, A.; Zuber, M. A review on synthesis, properties and applications of natural polymer based carrageenan blends and composites. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 96, 282–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbaszadeh, A.; MacNaughtan, W.; Sworn, G.; Foster, T.J. New insights into xanthan synergistic interactions with konjac glucomannan: A novel interaction mechanism proposal. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 144, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, M.; Alimi, M.; Shokoohi, S.; Golchoobi, L. Synergistic interactions between konjac-mannan and xanthan/tragacanth gums in tomato ketchup: Physical, rheological and textural properties. J. Texture Stud. 2018, 49, 586–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, W.; Kang, M.; Luo, D.; Li, L.; Yin, Y.; Zhang, L. Preparation and swallowing properties of whey protein gel modified with konjac glucomannan for dysphagia food. Food Meas. 2025, 19, 5909–5918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, S.; Li, Y.; Liu, K.; Wang, H.; El-Aty, A.M.A.; Tan, M. Salmon protein gel enhancement for dysphagia diets: Konjac glucomannan and composite emulsions as texture modifiers. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 258, 128805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles, H.; Zannidi, D.; Clegg, M.E.; Woodside, J.V.; McKenna, G.; Forde, C.G.; Bull, S.P.; Lignou, S.; Gallagher, J.; Faka, M.; et al. A systematic review of the factors affecting textural perception by older adults and their association with food choice and intake. Appetite 2025, 214, 108202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tura, M.; Gagliano, M.A.; Soglia, F.; Bendini, A.; Patrignani, F.; Petracci, M.; Gallina Toschi, T.; Valli, E. Consumer Perception and Liking of Parmigiano Reggiano Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) Cheese Produced with Milk from Cows Fed Fresh Forage vs. Dry Hay. Foods 2024, 13, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, A.; Kumar, L.; Serventi, L.; Schlich, P.; Torrico, D.D. Exploring the textural dynamics of dairy and plant-based yoghurts: A comprehensive study. Food Res. Int. 2023, 171, 113058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Song, C.; Lv, Y.; Qian, X. Konjac glucomannan/kappa carrageenan interpenetrating network hydrogels with enhanced mechanical strength and excellent self-healing capability. Polymer 2019, 184, 121913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wen, S.; Zuo, Q.; Wu, Y.; Li, X. Flotation separation of scheelite and calcite using the biopolymer konjac glucomannan: A novel and eco-friendly depressant. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2025, 32, 1056–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Jia, Y.; Li, P.; Yue, M.; Miu, Z.; Yin, Y.; Luo, D. Sodium caseinate active film loaded clove essential oil based on konjac glucomannan and xanthan gum: Physical and structural properties. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2024, 18, 2065–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Sun, N.; Wang, Y.; Lin, S. Formation and evaluation of caseingum Arabic coacervates via pH-dependent complexation using fast acidification. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 120, 783–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Wei, Y.; Jiao, X.; Jiang, Z.; Li, Z.; Ni, H. Effects of konjac glucomannan with different molecular weights on functional and structural properties of κ-carrageenan composite gel. Food Biophys. 2024, 19, 553–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adib, M.; Yaich, H.; Hidouri, H.; Ayadi, M.A. Effect of substituted gelling from pomegranate peel on colour, textural and sensory properties of pomegranate Jam. Food Chem. 2018, 239, 1047–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funami, T.; Nakauma, M. Instrumental food texture evaluation in relation to human perception. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 124, 107253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido, J.I.; Lozano, J.E.; Genovese, D.B. Effect of formulation variables on rheology, texture, colour, and acceptability of apple jelly: Modelling and optimization. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 62, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saroglu, O.; Karadag, A.; Cakmak, Z.H.T.; Karasu, S. The formulation and microstructural, rheological, and textural characterization of salep-xanthan gum-based liposomal gels. Polym. Bull. 2023, 80, 9941–9962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campo, V.L.; Kawano, D.F.; da Silva, D.B., Jr.; Carvalho, I. Carrageenans: Biological properties, chemical modifications and structural analysis—A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2009, 77, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, B.T.; Nicolai, T.; Benyahia, L.; Chassenieux, C. Synergistic effects of mixed salt on the gelation of κ-carrageenan. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 112, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekcan, Ö.; Tari, Ö. Cation effect on gel–sol transition of kappa carrageenan. Polym. Bull. 2008, 60, 569–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.A. Molecular interactions of plant and algal polysaccharides. Struct. Chem. 2009, 20, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sin, P.Y.; Tan, S.H.; Farida Asras, M.F.; Lee, C.M.; Lee, T.C.; Karim, M.d.R.; Ma, N.L. Exploring dual-coating strategies for probiotic microencapsulation using polysaccharide and protein systems. Discov. Food 2025, 5, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.; Zhang, M.; Adhikari, B.; Lin, J.; Luo, Z. Preparation and characterization of 3D printed texture-modified food for the elderly using mung bean protein, Rose powder, and flaxseed gum. J. Food Eng. 2024, 361, 111750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Kennedy, J.F.; Li, B.; Xu, X.; Xie, B.J. Characters of rice starch gel modified by gellan, carrageenan, and glucomannan: A texture profile analysis study. Carbohydr. Polym. 2007, 69, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, C.; Correia, E.; Dinis, L.-T.; Vilela, A. An overview of sensory characterization techniques: From classical descriptive analysis to the emergence of novel profiling methods. Foods 2022, 11, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, D.; Liu, J.; Yu, X. Effects of rice bran feruloyl oligosaccharides on gel properties and microstructure of grass carp surimi. Food Chem. 2023, 407, 135003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbuDujayn, A.A.; Mohamed, A.A.; Alamri, M.S.; Hussain, S.; Ibraheem, M.A.; Qasem, A.A.A.; Shamlan, G.; Alqahtani, N.K. Relationship between dough properties and baking performance of panned bread: The function of maltodextrins and natural gums. Molecules 2023, 28, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa-Ramírez, J.; Figueroa-Cárdenas, J.D.; Chuck-Hernández, C.; Garcia-Amezquita, L.E.; Dávila-Vega, J.P.; Casamayor, V.F.; Mariscal-Moreno, R.M. Agave inulin as a fat replacer in tamales: Physicochemical, nutritional, and sensory attributes. J Food Sci. 2023, 88, 4472–4482. [Google Scholar]

- Yeganehzad, S.; Kiumarsi, M.; Nadali, N.; Rabie Ashkezary, M. Formulation, development and characterization of a novel functional fruit snack based on fig (Ficus carica L.) coated with sugar-free chocolate. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikholeslami, Z.; Mahfouzi, M.; Karimi, M.; Hejrani, T.; Ghiafehdavoodi, M.; Ghodsi, M. Evaluating the traditional bread properties with new formula: Affected by triticale and cress seed gum. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2021, 5, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Xie, W.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Zhang, M.; Shao, J.H. Pickering emulsion stabilized by modified pea protein-chitosan composite particles as a new fat substitute improves the quality of pork sausages. Meat Sci. 2023, 197, 109086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cankurt, H.; Cavus, M.; Guner, O. The Use of Carrot Fiber and Some Gums in the Production of Block-Type Melting Cheese. Foods 2024, 13, 2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 11036; International Organization for Standardization (ISO)—Sensory Analysis—Methodology-Texture Profile. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/76668.html (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- Koç, H.; Vinyard, C.J.; Essick, G.K.; Foegeding, E.A. Food oral processing: Conversion of food structure to textural perception. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 4, 237–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Fan, J.; Han, C.; Du, C.; Wei, Z.; Du, D. Methods and instruments for the evaluation of food texture: Advances and perspectives. Food Res. Int. 2025, 208, 116162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forde, C.G.; Bolhuis, D. Interrelations between food form, texture, and matrix influence energy intake and metabolic responses. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2022, 11, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Andablo-Reyes, E.; Mighell, A.; Pavitt, S.; Sarkar, A. Dry mouth diagnosis and saliva substitutes-A review from a textural perspective. J. Texture Stud. 2021, 52, 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lavergne, M.; van de Velde, F.; Stieger, M. Bolus matters: The influence of food oral breakdown on dynamic texture perception. Food Funct. 2017, 8, 464–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Lavergne, M.D.; Tournier, C.; Bertrand, D.; Salles, C.; van de Velde, F.; Stieger, M. Dynamic texture perception, oral processing behaviour and bolus properties of emulsion-filled gels with and without contrasting mechanical properties. Food Hydrocoll. 2016, 52, 648–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shewan, H.M.; Stokes, J.R.; Smyth, H.E. Influence of particle modulus (softness) and matrix rheology on the sensory experience of ‘grittiness’ and ‘smoothness’. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 103, 105662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puleo, S.; Miele, N.A.; Cavella, S.; Masi, P.; Di Monaco, R. How sensory sensitivity to graininess could be measured? J. Texture Stud. 2020, 51, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pelsmaeker, S.; Behra, J.S.; Gellynck, X.; Schouteten, J.J. Detection threshold of chocolate graininess: Machine vs. human. British Food J. 2020, 122, 2757–2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Hollis, J.H. Relationship between chewing behavior and body weight status in fully dentate healthy adults. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2015, 66, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slyper, A. Oral processing, satiation and obesity: Overview and hypotheses. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2021, 14, 3399–3415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosca, A.C.; Torres, A.P.; Slob, E.; de Graaf, K.; McEwan, J.A.; Stieger, M. Small food texture modifications can be used to change oral processing behaviour and to control ad libitum food intake. Appetite 2019, 142, 104375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinelli, S.; Monteleone, E. Food Preferences and Obesity. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 36, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proserpio, C.; Laureati, M.; Invitti, C.; Pasqualinotto, L.; Bergamaschi, V.; Pagliarini, E. Cross-modal interactions for custard desserts differ in obese and normal weight Italian women. Appetite 2016, 100, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proserpio, C.; Verduci, E.; Zuccotti, G.; Pagliarini, E. Odor–taste–texture interactions as a promising strategy to tackle adolescent overweight. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merz, A.K.; Kramer, L.; Nettlau, A.; Hilbert, A.; Schmidt, R. Psychopathology in adults with co-occurring avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder and higher weight. Psychother. Psychosom. 2025, 22, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimura, S.; Hori, K.; Uehara, F.; Hori, S.; Yamaga, Y.; Hasegawa, Y.; Akazawa, K.; Ono, T. Relationship between body mass index and masticatory factors evaluated with a wearable device. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 4117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calcaterra, V.; Pizzorni, N.; Giovanazzi, S.; Nannini, M.; Scarponi, L.; Zanelli, S.; Zuccotti, G.; Schindler, A. Mastication and oral myofunctional status in excess weight children and adolescents: A cross-sectional observational study. J. Oral Rehabil. 2024, 51, 2345–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez Espinosa, Y.; Chen, J. Chapter 13. Applications of electromyography (EMG) technique for eating studies. In Food Oral Processing: Fundamentals of Eating and Sensory Perception; Chen, J., Engelen, L., Eds.; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Murashige, T.; Skoog, S.A. A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol. Plant. 1962, 15, 473–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rassu, G.; Salis, A.; Porcu, E.P.; Giunchedi, P.; Roldo, M.; Gavini, E. Composite chitosan/alginate hydrogel for controlled release of deferoxamine: A system to potentially treat iron dysregulation diseases. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 136, 1338–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghooneh, A.; Razavi, S.M.A.; Kasapis, S. Classification of hydrocolloids based on small amplitude oscillatory shear, large amplitude oscillatory shear, and textural properties. J. Texture Stud. 2019, 50, 520–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gel Formulation | Concentration of Gel (%) | Concentration of DC Callus Cells (%) | Porosity (%) (n = 8–12) | Moisture Content (%) (n = 8–12) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0DC-0.4gel | 0.4 | 0 | 9.54 ± 2.06 | 83.81 ± 0.3 |

| 0DC-0.5gel | 0.5 | 0 | 13.93 ± 1.21 | 84.73 ± 1.1 |

| 0DC-0.6gel | 0.6 | 0 | 13.60 ± 1.49 | 84.06 ± 0.71 |

| 0DC-0.7gel | 0.7 | 0 | 11.04 ± 1.32 | 83.20 ± 0.76 |

| 0DC-0.8gel | 0.8 | 0 | 11.64 ± 1.04 | 84.57 ± 1.25 |

| 0DC-0.9gel | 0.9 | 0 | 11.98 ± 2.07 | 84.69 ± 0.04 |

| 0DC-1.0gel | 1.0 | 0 | 12.03 ± 1.47 | 84.40 ± 0.63 |

| 0DC-1.5gel | 1.5 | 0 | 11.90 ± 0.56 | 83.06 ± 0.64 |

| 20DC-0.4gel | 0.4 | 20 | 28.93 ± 3.03 a | 85.40 ± 0.63 a |

| 60DC-0.4gel | 0.4 | 60 | 40.65 ± 3.12 a | 89.91 ± 0.34 a |

| 20DC-0.5gel | 0.5 | 20 | 28.69 ± 2.80 b | 86.10 ± 0.97 b |

| 60DC-0.5gel | 0.5 | 60 | 33.43 ± 2.18 b | 90.23 ± 0.72 b |

| 20DC-0.7gel | 0.7 | 20 | 26.18 ± 1.39 c | 85.72 ± 0.31 c |

| 60DC-0.7gel | 0.7 | 60 | 28.00 ± 1.11 c | 89.45 ± 0.16 c |

| 20DC-1.0gel | 1.0 | 20 | 19.78 ± 1.26 d | 85.97 ± 0.57 d |

| 60DC-1.0gel | 1.0 | 60 | 29.27 ± 2.10 d | 89.28 ± 0.15 d |

| Mechanical Properties | Concentration of Cell-Free Hydrogel | Concentration of Hydrogel with 20% Cells | Concentration of Hydrogel with 60% Cells | Cell Content in 0.4% Hydrogel | Cell Content in 1.0% Hydrogel |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hardness (N) | 0.955 *** | 0.975 *** | 0.977 *** | 0.180 * | 0.393 *** |

| Gumminess | 0.966 *** | 0.967 *** | 0.955 *** | –0.782 *** | –0.579 *** |

| Cohesiveness | –0.012 | 0.180 * | 0.792 *** | –0.813 *** | –0.765 *** |

| Springiness | –0.306 *** | –0.301 ** | 0.106 | –0.702 *** | –0.600 *** |

| Gel Formulation | Hardness (N) | Cohesiveness | Springiness | Gumminess |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0DC-0.4gel | 5.94 ± 0.93 a | 0.52 ± 0.12 a | 0.83 ± 0.07 a | 3.05 ± 0.53 a |

| 20DC-0.4gel | 6.36 ± 0.90 b | 0.41 ± 0.09 b | 0.75 ± 0.06 b | 2.64 ± 0.68 b |

| 60DC-0.4gel | 6.36 ± 0.67 b | 0.22 ± 0.04 c | 0.66 ± 0.08 c | 1.44 ± 0.36 c |

| 0DC-1.0gel | 18.00 ± 1.97 d | 0.52 ± 0.06 ad | 0.78 ± 0.07 d | 9.31 ± 1.02 d |

| 20DC-1.0gel | 18.56 ± 1.71 d | 0.44 ± 0.03 be | 0.71 ± 0.06 be | 8.35 ± 0.83 e |

| 60DC-1.0gel | 19.80 ± 1.84 f | 0.38 ± 0.04 f | 0.67 ± 0.03 cf | 7.58 ± 1.14 f |

| Parameters | 0DC-0.4gel | 20DC-0.4gel | 60DC-0.4gel | 0DC-1.0gel | 20DC-1.0gel | 60DC-1.0gel |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G’LVE (kPa) | 2.92 ± 0.07 a | 4.70 ± 0.18 b | 8.47 ± 0.14 c | 11.3 ± 0.6 d | 13.8 ± 0.7 e | 22.1 ± 0.2 f |

| G”LVE (kPa) | 0.28 ± 0.17 a | 0.73 ± 0.03 b | 1.60 ± 0.05 c | 1.1 ± 0.2 d | 2.0 ± 0.3 e | 4.2 ± 0.6 f |

| Tan [δ]LVE | 0.10 ± 0.01 a | 0.16 ± 0.01 b | 0.19 ± 0.01 c | 0.10 ± 0.03 a | 0.15 ± 0.03 b | 0.19 ± 0.04 c |

| Tan [δ]AF | 0.70 ± 0.25 a | 0.53 ± 0.07 a | 0.52 ± 0.05 a | 0.64 ± 0.11 a | 0.69 ± 0.06 a | 0.61 ± 0.01 a |

| τFr (Pa) | 57.3 ± 18.7 a | 72.3 ± 11.5 ab | 98.3 ± 29.4 b | 102.9 ± 11.0 b | 102.9 ± 11.0 b | 175.0 ± 34.7 c |

| γFr (%) | 4.35 ± 0.97 a | 3.98 ± 0.32 ab | 3.22 ± 0.67 b | 1.36 ± 0.57 cd | 0.91 ± 0.01 c | 1.69 ± 0.26 d |

| Gel Formulation | Hardness | Springiness | Adhesiveness | Swallowability | Juiciness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0DC-0.4gel | 10.2 ± 10.4 a | 29.1 ± 27.6 a | 12.4 ± 13.2 a | 88.7 ± 17.9 a | 54.3 ± 29.5 a |

| 20DC-0.4gel | 16.5 ± 14.8 a | 28.9 ± 21.7 a | 14.5 ± 13.6 a | 85.4 ± 15.5 a | 48.5 ± 23.4 a |

| 60DC-0.4gel | 28.5 ± 18.4 b | 26.5 ± 24.2 a | 21.8 ± 21.7 b | 76.9 ± 21.5 ab | 54.4 ± 23.7 a |

| 0DC-1.0gel | 56.5 ± 18.7 c | 60.5 ± 25.3 b | 15.8 ± 20.1 a | 71.6 ± 26.1 bc | 33.6 ± 22.5 b |

| 20DC-1.0gel | 49.3 ± 22.5 c | 50.1 ± 25.6 b | 18.0 ± 20.2 ab | 72.5 ± 24.6 c | 36.7 ± 20.0 b |

| 60DC-1.0gel | 52.0 ± 26.5 c | 51.0 ± 28.9 b | 22.1 ± 21.9 b | 65.3 ± 29.9 c | 43.5 ± 25.9 ab |

| Sensory Attributes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hardness | Springiness | Adhesiveness | Swallowability | Juiciness | |

| Hardness (N) | 0.652 *** | 0.441 *** | 0.075 | −0.295 *** | −0.276 *** |

| Cohesiveness | 0.050 | 0.205 ** | −0.147 * | 0.065 | −0.144 |

| Springiness | −0.278 | −0.022 | −0.183 * | 0.216 ** | 0.003 |

| Gumminess | 0.614 *** | 0.459 *** | 0.024 | −0.245 *** | −0.300 *** |

| Graininess | Hardness | Springiness | Adhesiveness | Swallowability | Juiciness | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graininess | - | 0.134 | 0.105 | 0.207 ** | −0.126 | 0.317 *** |

| Hardness | - | 0.374 *** | 0.141 | −0.337 *** | −0.128 | |

| Springiness | - | 0.248 *** | −0.344 *** | −0.109 | ||

| Adhesiveness | - | −0.316 *** | 0.050 | |||

| Swallowability | - | −0.056 | ||||

| Juiciness | - |

| Gel Formulation | Chewing Time (s) | Number of Chews | M. Masseter (mV × ms) | M. Temporalis (mV × ms) | mm. Suprahyoidei (mV × ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0DC-0.4gel | 15 ± 8 a | 18 ± 9 a | 150 ± 94 a | 180 ± 140 a | 295 ± 193 a |

| 20DC-0.4gel | 16 ± 8 a | 20 ± 9 a | 200 ± 13 b | 239 ± 208 b | 314 ± 179 a |

| 60DC-0.4gel | 17 ± 9 a | 20 ± 12 a | 181 ± 96 b | 275 ± 192 c | 340 ± 207 a |

| 0DC-1.0gel | 21 ± 10 b | 29 ± 15 b | 217 ± 106 c | 290 ± 166 c | 398 ± 178 b |

| 20DC-1.0gel | 22 ± 11 b | 31 ± 17 b | 244 ± 155 c | 332 ± 257 c | 443 ± 228 b |

| 60DC-1.0gel | 22 ± 10 b | 31 ± 16 b | 280 ± 177 d | 411 ± 323 d | 457 ± 234 c |

| Gel Formulation | Mean Amplitude (mV) | Activity (mV × ms) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal BMI | High BMI | Normal BMI | High BMI | |

| 0DC-0.4gel | 20.3 ± 5.8 | 16.0 ± 3.5 * | 319 ± 202 | 263 ± 186 |

| 20DC-0.4gel | 21.4 ± 9.8 | 16.4 ± 10.5 | 349 ± 196 | 252 ± 125 |

| 60DC-0.4gel | 22.2 ± 5.0 | 17.0 ± 5.0 * | 369 ± 224 | 281 ± 168 |

| 0DC-1.0gel | 21.4 ± 4.8 | 17.2 ± 4.4 * | 428 ± 170 | 333 ± 166 |

| 20DC-1.0gel | 21.4 ± 4.5 | 17.4 ± 4.2 * | 482 ± 226 | 372 ± 193 |

| 60DC-1.0gel | 23.6 ± 5.3 | 16.8 ± 5.4 * | 522 ± 204 | 339 ± 192 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Günter, E.; Popeyko, O.; Zueva, N.; Velskaya, I.; Vityazev, F.; Popov, S. Texture Properties and Chewing of κ-Carrageenan–Konjac Gum–Milk Hydrogels Modified with Carrot Callus Cells. Gels 2025, 11, 990. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120990

Günter E, Popeyko O, Zueva N, Velskaya I, Vityazev F, Popov S. Texture Properties and Chewing of κ-Carrageenan–Konjac Gum–Milk Hydrogels Modified with Carrot Callus Cells. Gels. 2025; 11(12):990. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120990

Chicago/Turabian StyleGünter, Elena, Oxana Popeyko, Natalia Zueva, Inga Velskaya, Fedor Vityazev, and Sergey Popov. 2025. "Texture Properties and Chewing of κ-Carrageenan–Konjac Gum–Milk Hydrogels Modified with Carrot Callus Cells" Gels 11, no. 12: 990. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120990

APA StyleGünter, E., Popeyko, O., Zueva, N., Velskaya, I., Vityazev, F., & Popov, S. (2025). Texture Properties and Chewing of κ-Carrageenan–Konjac Gum–Milk Hydrogels Modified with Carrot Callus Cells. Gels, 11(12), 990. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120990