Rheology and Moisture-Responsive Adhesion of Hydroxypropyl Cellulose-Enhanced Polyvinylpyrrolidone–Polyethylene Glycol Hydrogels

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Characterization of PVP/PEG Hydrogels Modified with HPC

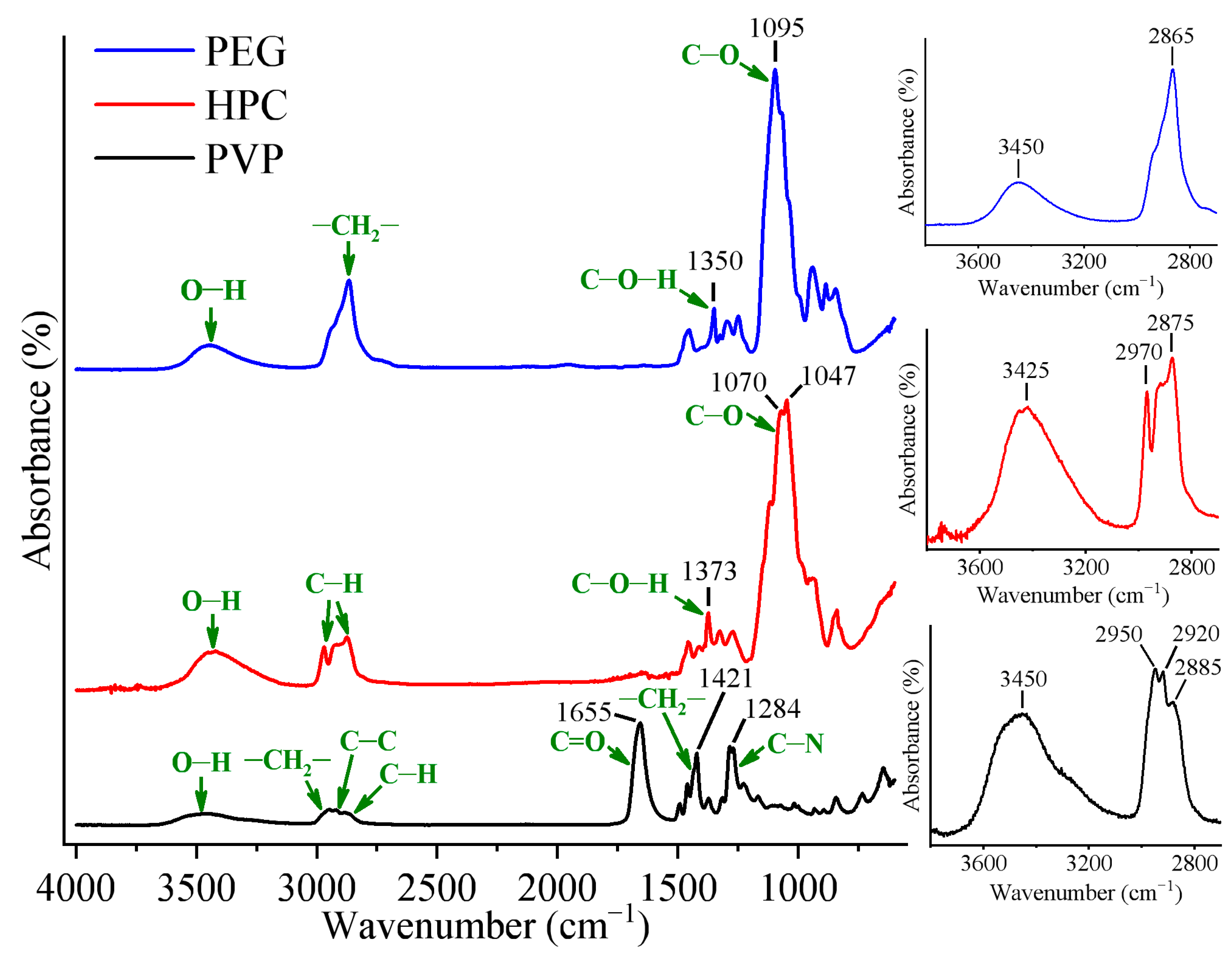

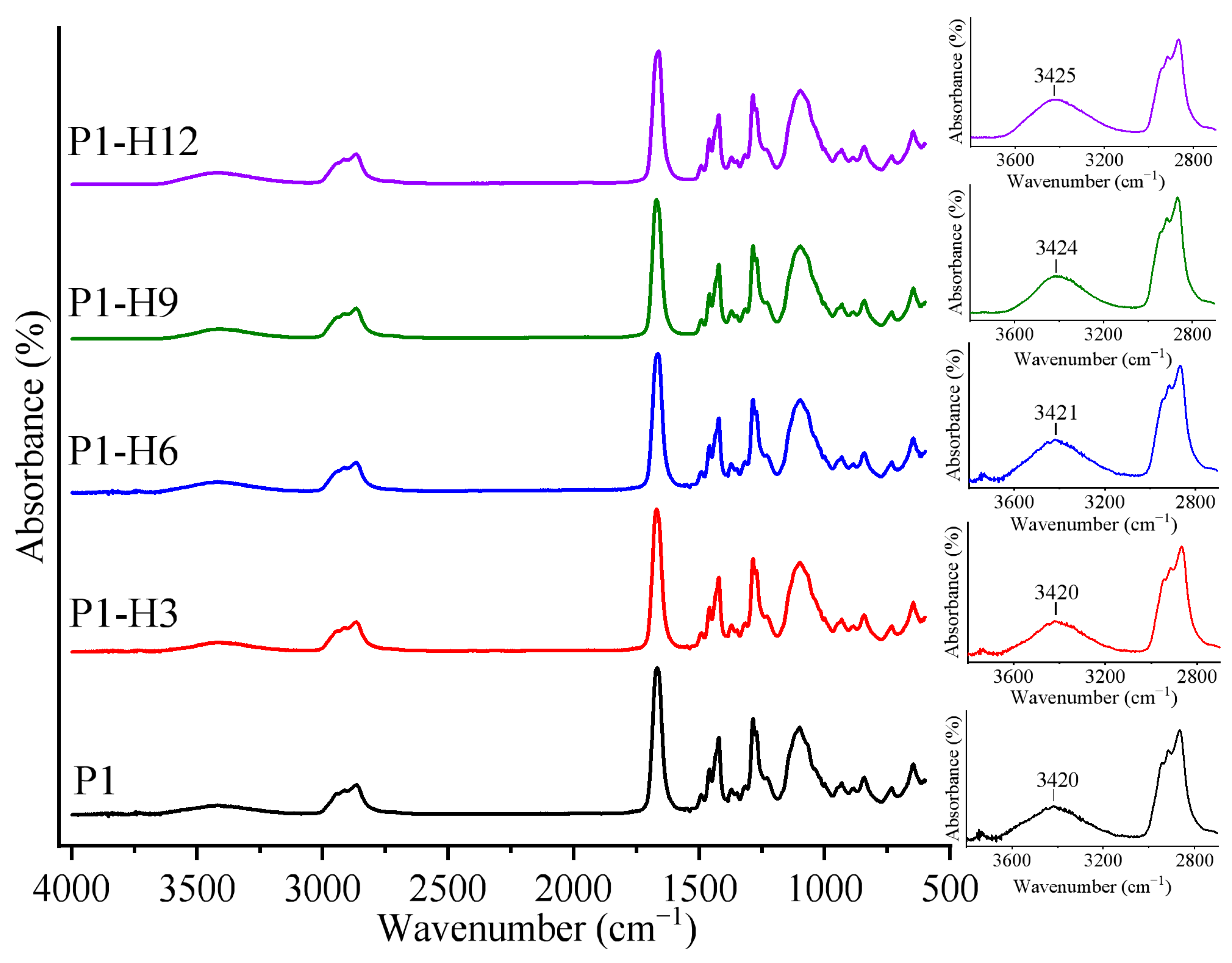

2.1.1. IR Analysis of PVP/PEG Hydrogels Modified with HPC

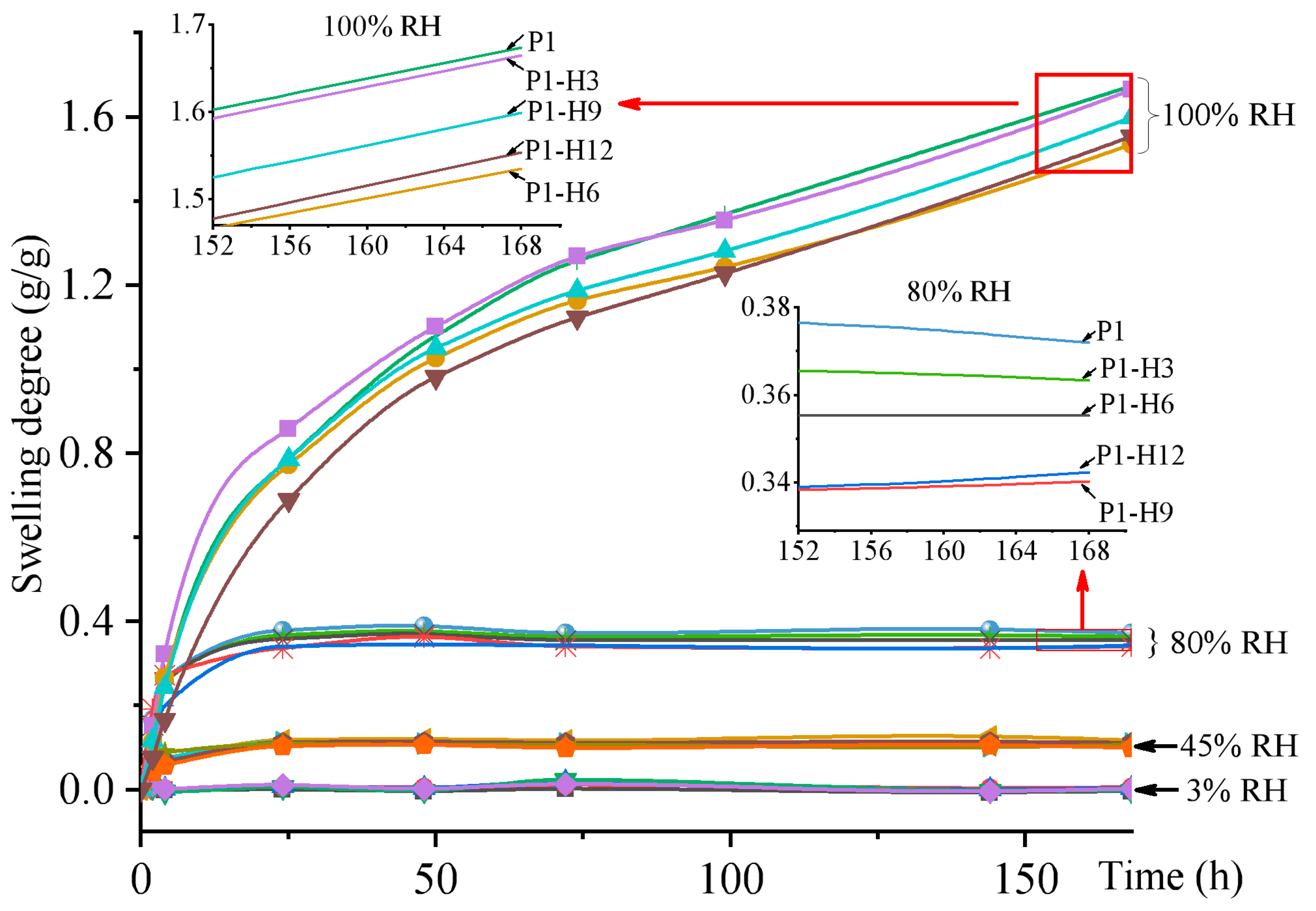

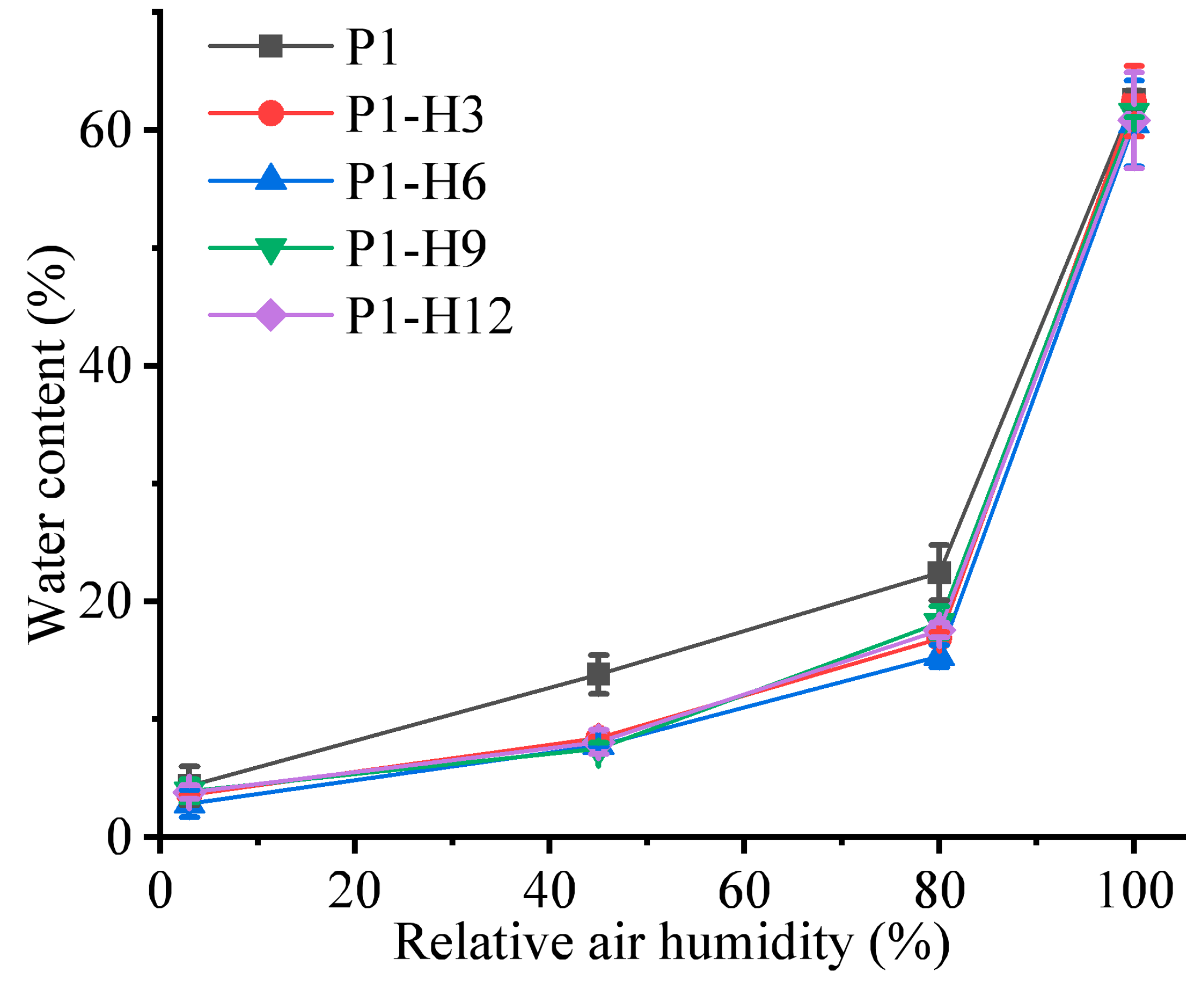

2.1.2. Swelling and Water Content in PVP/PEG Hydrogels Modified with HPC

2.2. Adhesion Properties of PVP/PEG Hydrogels Modified with HPC

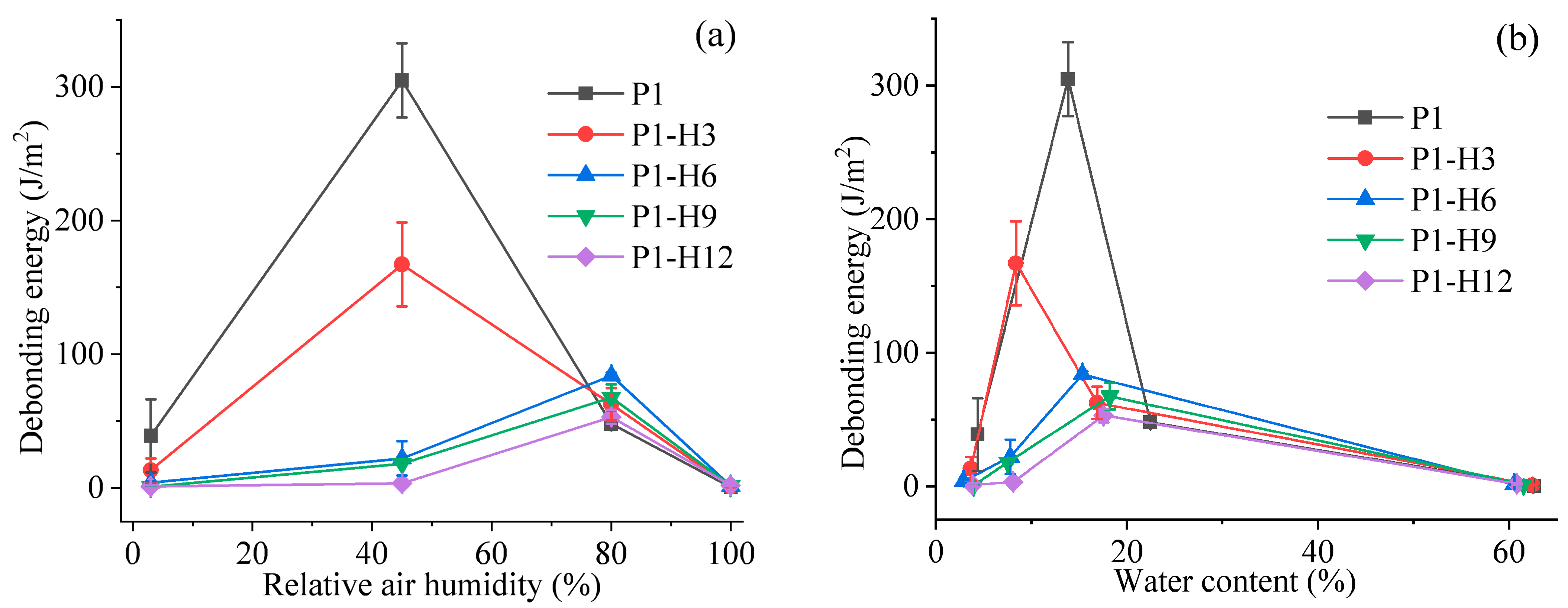

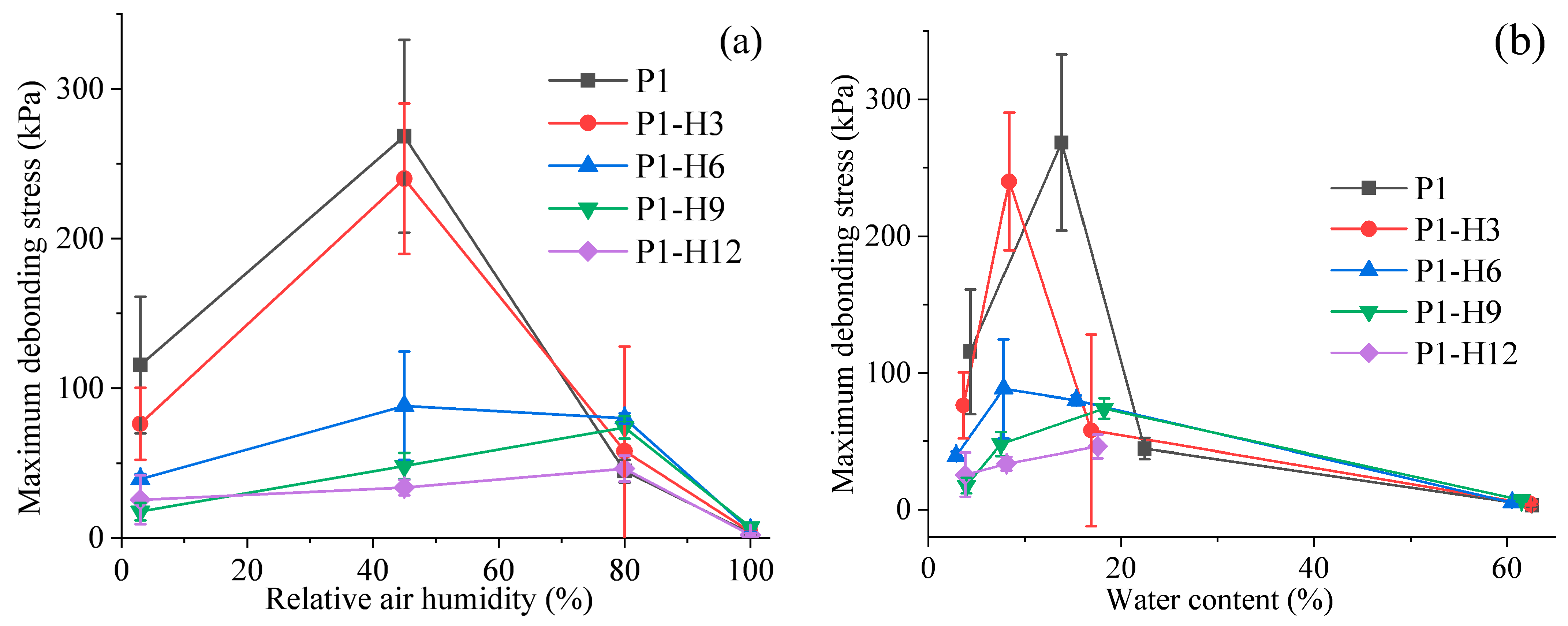

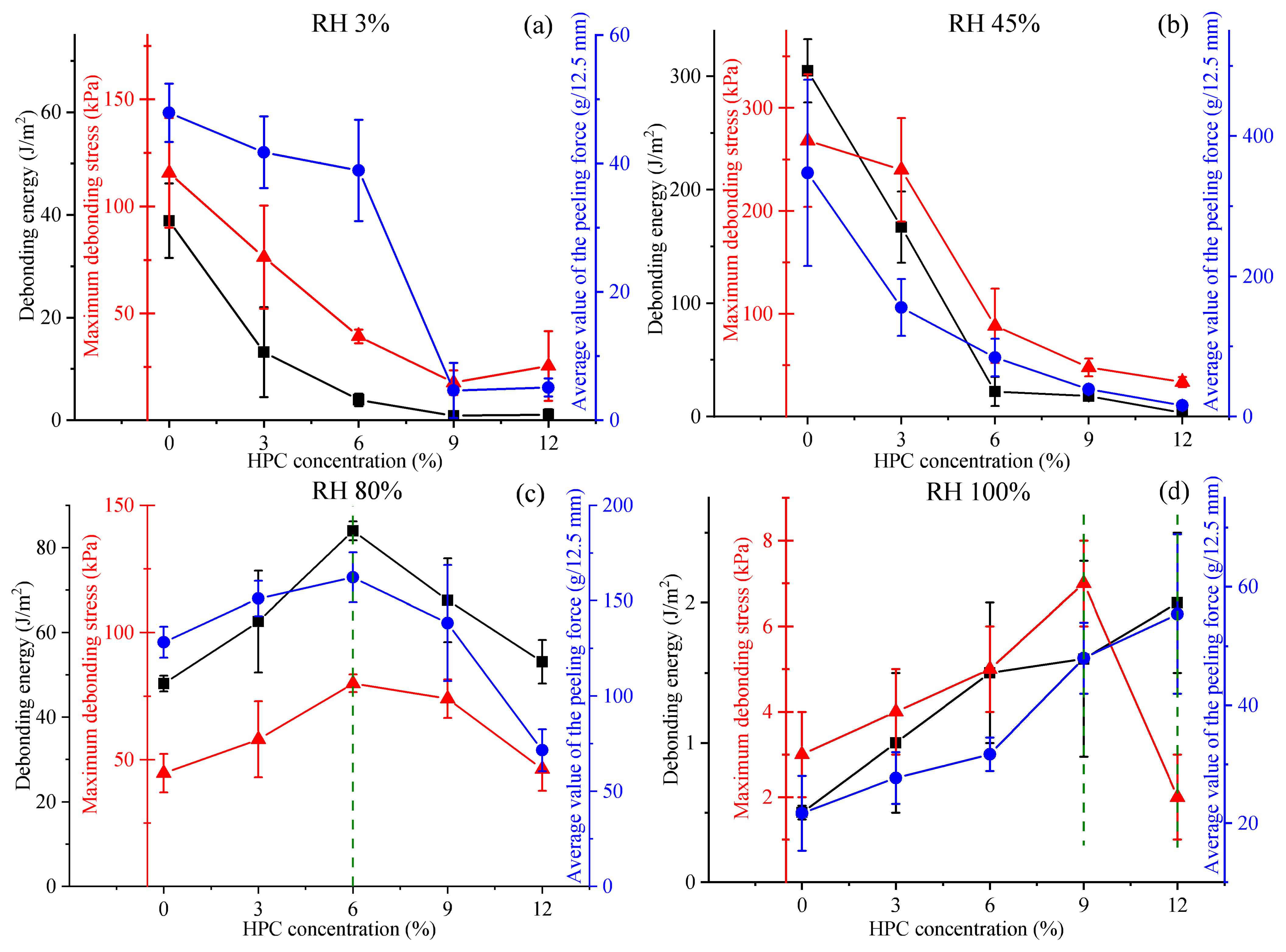

2.2.1. Tack Testing

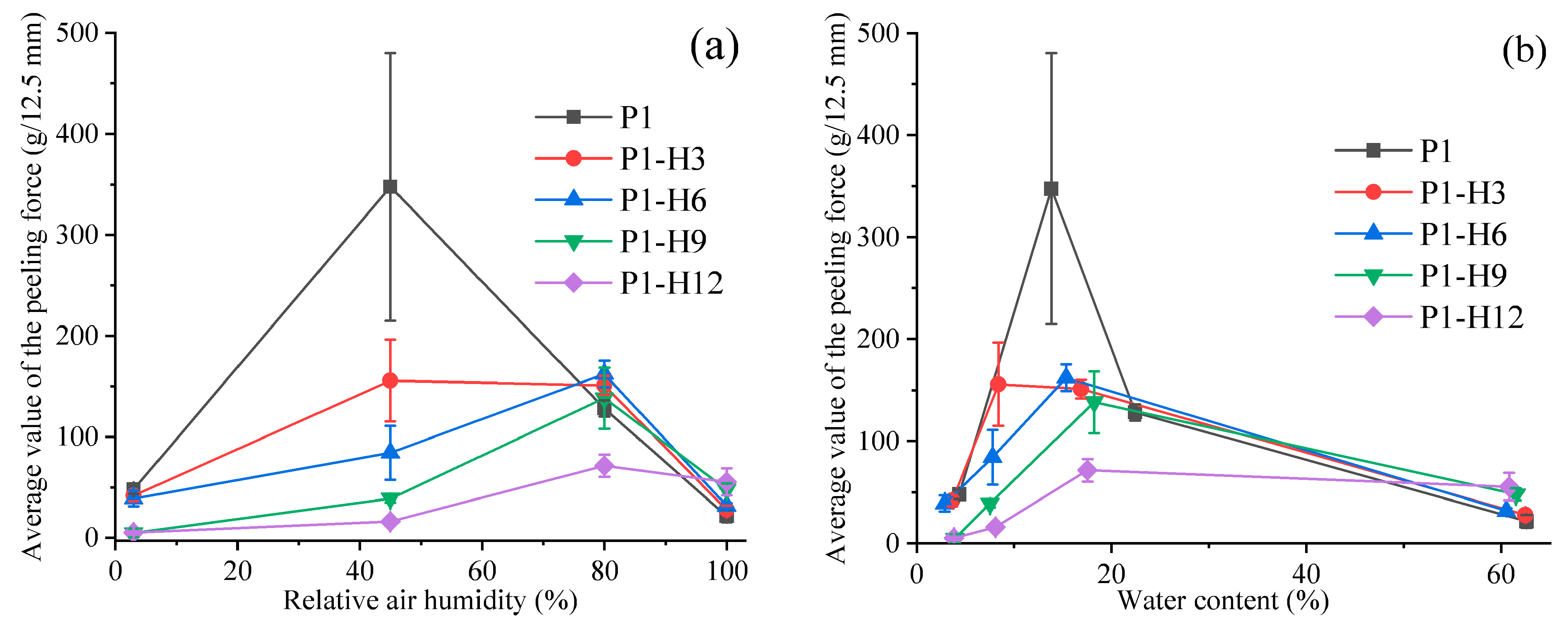

2.2.2. Peel Testing

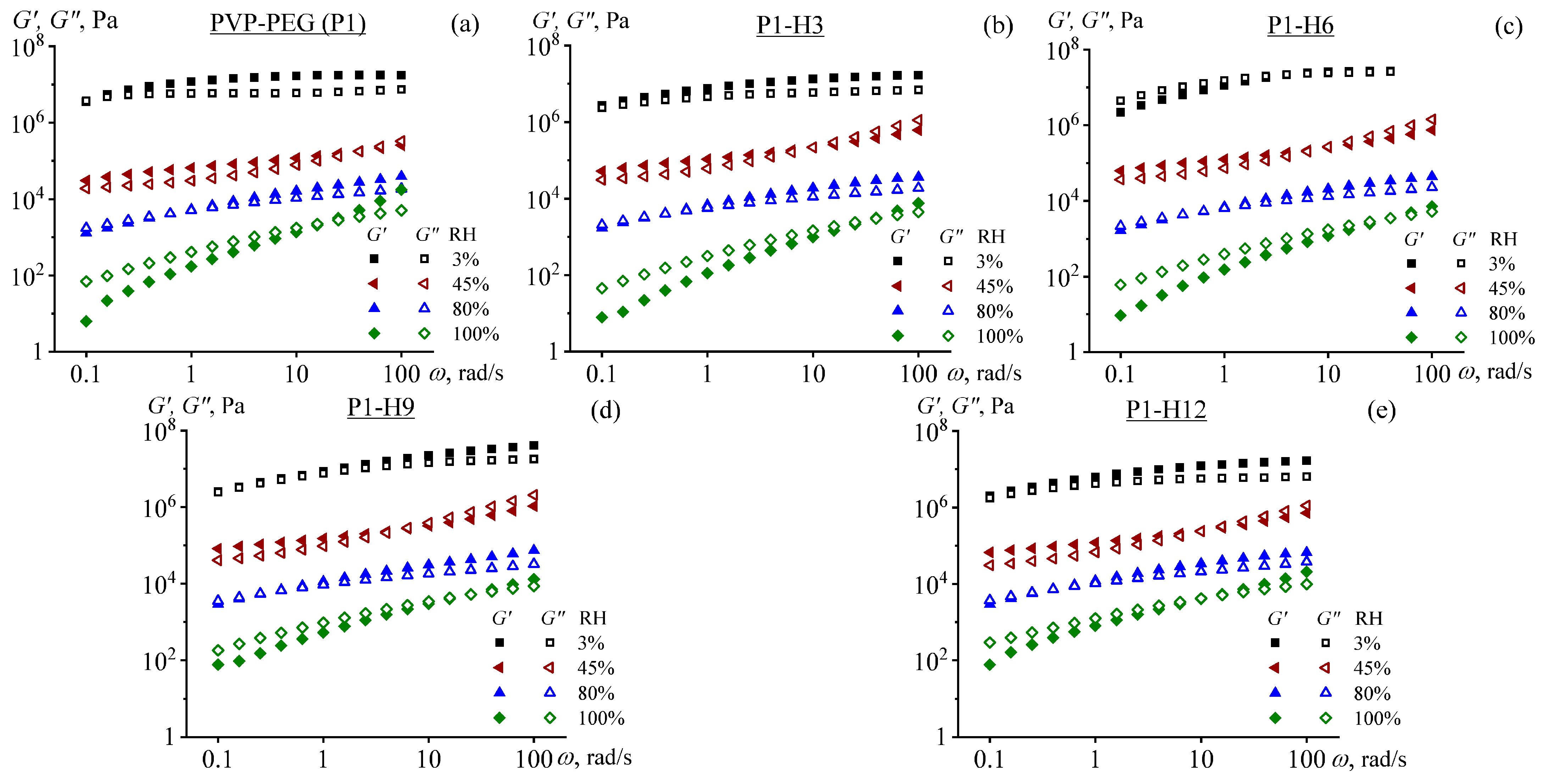

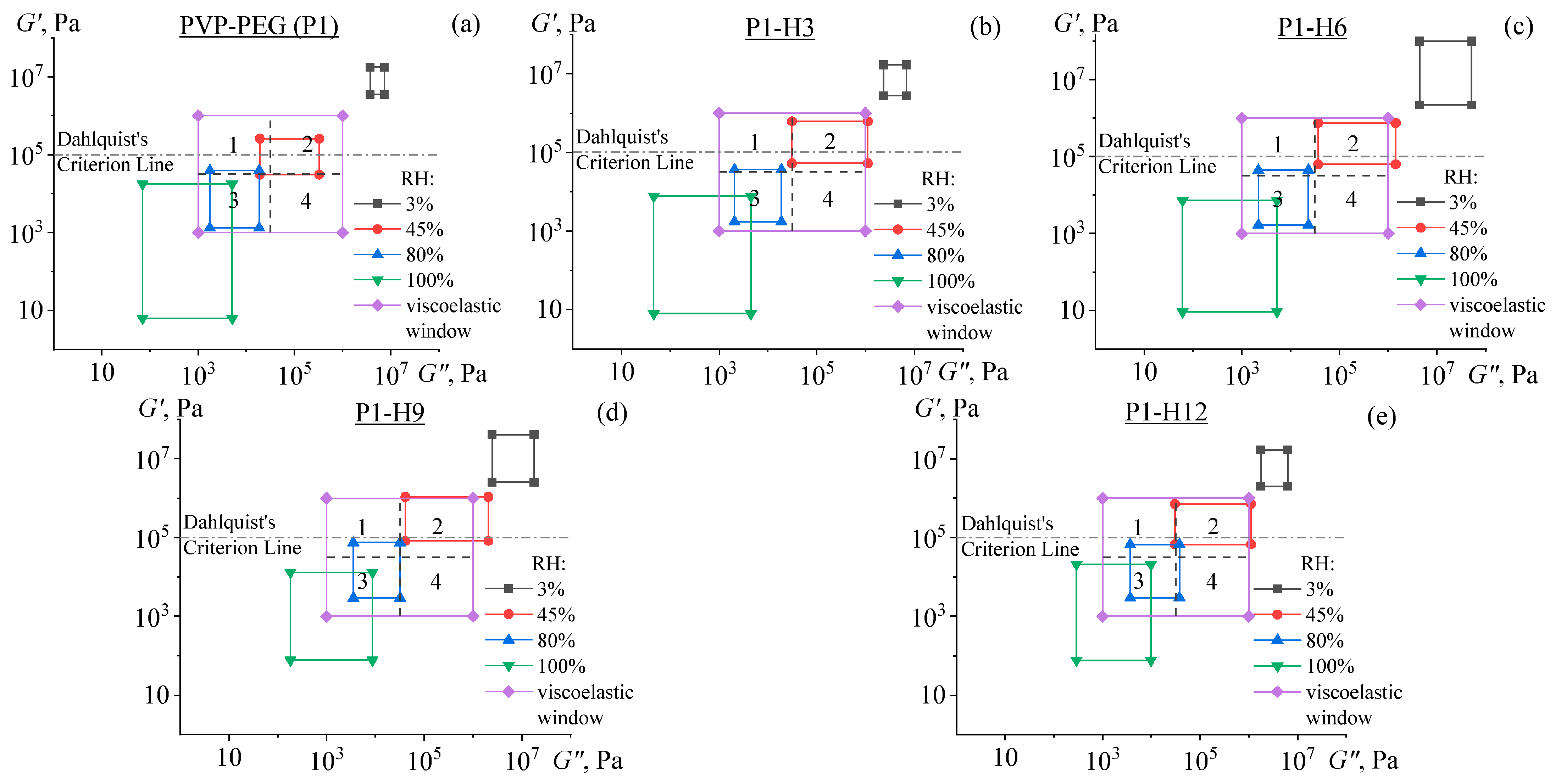

2.3. Rheological Properties of PVP/PEG Hydrogels Modified with HPC

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Methods

4.2.1. Preparation of Hydrogel Films

4.2.2. Infrared Spectroscopy

4.2.3. Water Content and Swelling Degree Measurements

4.2.4. Probe Tack Test

4.2.5. 90-Degree Peel Test

4.2.6. Rheological Properties

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ullah, F.; Othman, M.B.H.; Javed, F.; Ahmad, Z.; Akil, H.M. Classification, Processing and Application of Hydrogels: A Review. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2015, 57, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, S.; Hina, M.; Iqbal, J.; Rajpar, A.H.; Mujtaba, M.A.; Alghamdi, N.A.; Wageh, S.; Ramesh, K.; Ramesh, S. Fundamental Concepts of Hydrogels: Synthesis, Properties, and Their Applications. Polymers 2020, 12, 2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, P.; Sharma, M.; Devi, M. Hydrogels: An Overview of Its Classifications, Properties, and Applications. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2023, 147, 106145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, A.S. Hydrogels for Biomedical Applications. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2012, 64, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, E.M. Hydrogel: Preparation, Characterization, and Applications: A Review. J. Adv. Res. 2015, 6, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.; Park, J.; Kim, S.; Cho, H.; Kim, H.J.; Park, S.; Shin, D.S. Tailored Hydrogels for Biosensor Applications. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2020, 89, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Gong, J.P. Design Principles for Strong and Tough Hydrogels. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2024, 9, 380–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyin, S.O.; Kulichikhin, V.G.; Malkin, A.Y. The Rheological Characterisation of Typical Injection Implants Based on Hyaluronic Acid for Contour Correction. Rheol. Acta 2016, 55, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejo-Otero, A.; Fenollosa-Artés, F.; Achaerandio, I.; Rey-Vinolas, S.; Buj-Corral, I.; Mateos-Timoneda, M.Á.; Engel, E. Soft-Tissue-Mimicking Using Hydrogels for the Development of Phantoms. Gels 2022, 8, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Lei, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, T.; Jiang, Z.; Zhou, L.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Y.; et al. Hydrogels with Brain Tissue-like Mechanical Properties in Complex Environments. Mater. Des. 2023, 234, 112338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Lu, J.; Ji, T.; Xue, Y.; Zhao, L.; Zhao, K.; Jia, B.; Wang, B.; Wang, J.; Zhang, S.; et al. Self-Healing Hydrogel Bioelectronics. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2306350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Zhang, J.; Wei, Z.; Zhang, B.; Weng, X. Advances and Progress in Self-Healing Hydrogel and Its Application in Regenerative Medicine. Materials 2023, 16, 1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farazin, A.; Shirazi, F.A.; Shafiei, M. Natural Biomarocmolecule-Based Antimicrobial Hydrogel for Rapid Wound Healing: A Review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 244, 125454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Qin, M.; Xu, M.; Miao, F.; Merzougui, C.; Zhang, X.; Wei, Y.; Chen, W.; Huang, D. The Fabrication of Antibacterial Hydrogels for Wound Healing. Eur. Polym. J. 2021, 146, 110268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Jia, S.; Yue, S.; Wang, C.; Qiu, H.; Ji, Y.; Cao, M.; Zhang, D. Hydrogel-Stabilized Zinc Ion Batteries: Progress and Outlook. Green Chem. 2024, 26, 6404–6422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Xu, T.; Zhang, X. Multifunctional Conductive Hydrogel-Based Flexible Wearable Sensors. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2021, 134, 116130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwala, S. Electrically Conducting Hydrogels for Health Care: Concept, Fabrication Methods, and Applications. Int. J. Bioprinting 2020, 6, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Yu, H.; Wang, L.; Huang, Z.; Haq, F.; Teng, L.; Jin, M.; Ding, B. Recent Advances on Designs and Applications of Hydrogel Adhesives. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 9, 2101038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, T.C.; Chang, C.C.; Chan, H.P.; Chung, T.W.; Shu, C.W.; Chuang, K.P.; Duh, T.H.; Yang, M.H.; Tyan, Y.C. Hydrogels: Properties and Applications in Biomedicine. Molecules 2022, 27, 2902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Cid, P.; Jiménez-Rosado, M.; Romero, A.; Pérez-Puyana, V. Novel Trends in Hydrogel Development for Biomedical Applications: A Review. Polymers 2022, 14, 3023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, A.; Patel, D.; Hickson, B.; Desrochers, J.; Hu, X. Recent Progress in Biopolymer-Based Hydrogel Materials for Biomedical Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erfani, A.; Diaz, A.E.; Doyle, P.S. Hydrogel-Enabled, Local Administration and Combinatorial Delivery of Immunotherapies for Cancer Treatment. Mater. Today 2023, 65, 227–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xu, X.; Xu, M.; Geng, Z.; Ji, P.; Liu, Y. Hydrogel Systems for Targeted Cancer Therapy. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1140436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Chen, K. Advances in Hydrogel-Based Drug Delivery Systems. Gels 2024, 10, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, H.; Faheem, S.; Paiva-Santos, A.C.; Sarwar, H.S.; Jamshaid, M. A Comprehensive Review of Hydrogel-Based Drug Delivery Systems: Classification, Properties, Recent Trends, and Applications. AAPS PharmSciTech 2024, 25, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, X.; Hu, Y.; Wang, S.; Chen, X.; Jiang, Y.; Su, J. Fabrication of Physical and Chemical Crosslinked Hydrogels for Bone Tissue Engineering. Bioact. Mater. 2022, 12, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, B.; Gosecka, M.; Bodaghi, M.; Crespy, D.; Youssef, G.; Dodda, J.M.; Wong, S.H.D.; Imran, A.B.; Gosecki, M.; Jobdeedamrong, A.; et al. Engineering Multifunctional Dynamic Hydrogel for Biomedical and Tissue Regenerative Applications. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 487, 150403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Chee, P.L.; Sugiarto, S.; Yu, Y.; Shi, C.; Yan, R.; Yao, Z.; Shi, X.; Zhi, J.; Kai, D.; et al. Hydrogel-Based Flexible Electronics. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2205326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Cheng, Y.; Deng, Y.; Wen, F.; Lai, Y.; Li, H. Conductive Hydrogel for Flexible Bioelectronic Device: Current Progress and Future Perspective. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2308974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, C.F.; Ahmed, R.; Marques, A.P.; Reis, R.L.; Demirci, U. Engineering Hydrogel-Based Biomedical Photonics: Design, Fabrication, and Applications. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2006582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Zhong, J.; Sun, F.; Liu, B.; Peng, Z.; Lian, J.; Wu, X.; Li, L.; Hao, M.; Zhang, T. Hydrogel Sensors for Biomedical Electronics. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 481, 148317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, P.; Shojaei, A. A Review on the Features, Performance and Potential Applications of Hydrogel-Based Wearable Strain/Pressure Sensors. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 298, 102553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Li, J.; Ding, Q.; Wang, H.; Liu, C.; Wu, J. Functionalized Hydrogel-Based Wearable Gas and Humidity Sensors. Nano-Micro Lett. 2023, 15, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, X.; Li, J.; Ma, N.; Ma, X.; Gao, M. Bacterial Cellulose Hydrogel for Sensors. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 461, 142062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Li, J.; Liang, J.; Zhang, K.; Li, J. Hydrogel Preparation Methods and Biomaterials for Wound Dressing. Life 2021, 11, 1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Qiu, P.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, L.; Gou, D. Chitosan-Based Hydrogel Wound Dressing: From Mechanism to Applications, a Review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 244, 125250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Huang, C.; Liu, H.; Chen, H.; Shou, J.; Cheng, H.; Liu, G. Natural Hydrogel Dressings in Wound Care: Design, Advances, and Perspectives. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2024, 35, 109442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, A.; Tian, W.-X.; Farooq, M.A.; Khan, D.H. An Overview of Hydrogels and Their Role in Transdermal Drug Delivery. Int. J. Polym. Mater. Polym. Biomater. 2021, 70, 574–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, A.; Alexander, S.; Luo, W.; Al-Salam, N.; Van Oirschot, M.; Ranganath, S.H.; Chakrabarti, S.; Paul, A. Engineering Multifunctional Adhesive Hydrogel Patches for Biomedical Applications. Interdiscip. Med. 2023, 1, e20230008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.H.D.; Deen, G.R.; Bates, J.S.; Maiti, C.; Lam, C.Y.K.; Pachauri, A.; AlAnsari, R.; Bělský, P.; Yoon, J.; Dodda, J.M. Smart Skin-Adhesive Patches: From Design to Biomedical Applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2213560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mapari, S.; Mestry, S.; Mhaske, S.T. Developments in Pressure-Sensitive Adhesives: A Review. Polym. Bull. 2021, 78, 4075–4108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, M.; Ruan, L.; Dong, X.; Tian, S.; Lang, W.; Wu, M.; Chen, Y.; Lv, Q.; Lei, L. Current State of Knowledge on Intelligent-Response Biological and Other Macromolecular Hydrogels in Biomedical Engineering: A Review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 227, 472–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Yang, X.; Lai, P.; Shang, L. Bio-inspired Adhesive Hydrogel for Biomedicine—Principles and Design Strategies. Smart Med. 2022, 1, e20220024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldstein, M.M.; Siegel, R.A. Molecular and Nanoscale Factors Governing Pressure-Sensitive Adhesion Strength of Viscoelastic Polymers. J. Polym. Sci. Part B Polym. Phys. 2012, 50, 739–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldstein, M.M.; Dormidontova, E.E.; Khokhlov, A.R. Pressure Sensitive Adhesives Based on Interpolymer Complexes. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2015, 42, 79–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedek, I.; Feldstein, M.M. Fundamentals of Pressure Sensitivity; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wirthl, D.; Pichler, R.; Drack, M.; Kettlguber, G.; Moser, R.; Gerstmayr, R.; Hartmann, F.; Bradt, E.; Kaltseis, R.; Siket, C.M.; et al. Instant Tough Bonding of Hydrogels for Soft Machines and Electronics. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yao, M.; Luo, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, Z.; Liang, C.; Qin, C.; Huang, C.; Yao, S. Polydopamine-Reinforced Hemicellulose-Based Multifunctional Flexible Hydrogels for Human Movement Sensing and Self-Powered Transdermal Drug Delivery. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 5883–5896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, B.; Liu, J. Smart Stimuli-Responsive Chitosan Hydrogel for Drug Delivery: A Review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 235, 123902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Chen, H.; Fang, Y.; Wu, J. Hydrogel Combined with Phototherapy in Wound Healing. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2022, 11, 2200494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Li, M.; Liu, A. A Review on Mechanical Properties of Pressure Sensitive Adhesives. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2013, 41, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, F.C.; Calixto, G.; Hatakeyama, I.N.; Luz, G.M.; Gremião, M.P.D.; Chorilli, M. Rheological, Mechanical, and Bioadhesive Behavior of Hydrogels to Optimize Skin Delivery Systems. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2013, 39, 1750–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyin, S.O. Structural Rheology in the Development and Study of Complex Polymer Materials. Polymers 2024, 16, 2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Bai, R.; Chen, B.; Suo, Z. Hydrogel Adhesion: A Supramolecular Synergy of Chemistry, Topology, and Mechanics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 1901693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.; Bai, Y.; Qin, X.; Liu, J.; Huang, W.; Lv, Q. Current Understanding of Hydrogel for Drug Release and Tissue Engineering. Gels 2022, 8, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Duan, L.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, J.; Zhang, K. Current Hydrogel Advances in Physicochemical and Biological Response-Driven Biomedical Application Diversity. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gun’ko, V.M.; Savina, I.N.; Mikhalovsky, S.V. Properties of Water Bound in Hydrogels. Gels 2017, 3, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Sayed, M.M. Production of Polymer Hydrogel Composites and Their Applications. J. Polym. Environ. 2023, 31, 2855–2879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, Q.; Dai, Z.; Dai, Y.; Xia, F.; Zhang, X. Nanocomposite Adhesive Hydrogels: From Design to Application. J. Mater. Chem. B 2021, 9, 585–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazaridou, A.; Biliaderis, C.G.; Kontogiorgos, V. Molecular Weight Effects on Solution Rheology of Pullulan and Mechanical Properties of Its Films. Carbohydr. Polym. 2003, 52, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tordi, P.; Tamayo, A.; Jeong, Y.; Bonini, M.; Samorì, P. Multiresponsive Ionic Conductive Alginate/Gelatin Organohydrogels with Tunable Functions. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2410663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishida, K.; Ikura, R.; Yamaoka, K.; Urakawa, O.; Konishi, T.; Inoue, T.; Matsuba, G.; Tanaka, M.; Takashima, Y. Relation between the Water Content and Mechanical Properties of Hydrogels with Movable Cross-Links. Macromolecules 2024, 57, 7745–7754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Y. Designing Ultrahigh-Water-Content, Tough, and Crack-Resistant Hydrogels by Balancing Chemical Cross-Linking and Physical Entanglement. ACS Appl. Eng. Mater. 2024, 2, 638–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldstein, M.M.; Lebedeva, T.L.; Shandryuk, G.A.; Kotomin, S.V.; Kuptsov, S.A.; Igonin, V.E.; Grokhovskaya, T.E.; Kulichikhin, V.G. Complex Formation in Poly(Vinyl Pyrrolidone)-Poly(Ethylene Glycol) Blends. Polym. Sci. Ser. A 1999, 41, 1316–1330. [Google Scholar]

- Novikov, M.B.; Borodulina, T.A.; Kotomin, S.V.; Kulichikhin, V.G.; Feldstein, M.M. Relaxation Properties of Pressure-Sensitive Adhesives upon Withdrawal of Bonding Pressure. J. Adhes. 2005, 81, 77–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novikov, M.B.; Roos, A.; Creton, C.; Feldstein, M.M. Dynamic Mechanical and Tensile Properties of Poly(N-Vinyl Pyrrolidone)-Poly (Ethylene Glycol) Blends. Polymer 2003, 44, 3561–3578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldstein, M.M. Peculiarities of Glass Transition Temperature Relation to the Composition of Poly(N-Vinyl Pyrrolidone) Blends with Short Chain Poly(Ethylene Glycol). Polymer 2001, 42, 7719–7726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urtti, A.; Juslin, M.; Miinalainen, O. Pilocarpine Release from Hydroxypropyl-Cellulose-Polyvinylpyrrolidone Matrices. Int. J. Pharm. 1985, 25, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkoç, T.; Sevgili, L.M.; Çavuş, S. Hydroxypropyl Cellulose/Polyvinylpyrrolidone Matrix Tablets Containing Ibuprofen: Infiltration, Erosion and Drug Release Characteristics. ChemistrySelect 2022, 7, e202202180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, K.S.; Prabhakar, M.N.; Reddy, V.N.; Sathyamaiah, G.; Maruthi, Y.; Subha, M.C.S.; Chowdoji Rao, K. Miscibility Studies of Hydroxypropyl Cellulose/Poly(Vinyl Pyrrolidone) in Dilute Solutions and Solid State. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2012, 125, 2289–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansur, H.S.; Sadahira, C.M.; Souza, A.N.; Mansur, A.A.P. FTIR Spectroscopy Characterization of Poly (Vinyl Alcohol) Hydrogel with Different Hydrolysis Degree and Chemically Crosslinked with Glutaraldehyde. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2008, 28, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnikova, O.A.; Samkova, I.A.; Melnikov, M.Y.; Petrov, A.Y.; Eltsov, O.S. IR Spectroscopic Study of Chemical Structure of Polymer Complexes of Medicinal Substances Based on Polyvinylpyrrolidone. Adv. Curr. Nat. Sci. 2016, 8, 42–49. [Google Scholar]

- Rozenberg, M.; Loewenschuss, A.; Marcus, Y. IR Spectra and Hydration of Short-Chain Polyethyleneglycols. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 1998, 54, 1819–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Newehy, M.H.; El-Naggar, M.E.; Alotaiby, S.; El-Hamshary, H.; Moydeen, M.; Al-Deyab, S. Green Electrospining of Hydroxypropyl Cellulose Nanofibres for Drug Delivery Applications. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2017, 18, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paisana, M.; Wahl, M.; Pinto, J. Role of Polymeric Excipients in the Stabilization of Olanzapine When Exposed to Aqueous Environments. Molecules 2015, 20, 22364–22382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bairamov, D.F.; Chalykh, A.E.; Feldstein, M.M.; Siegel, R.A. Impact of Molecular Weight on Miscibility and Interdiffusion between Poly(N-Vinyl Pyrrolidone) and Poly(Ethylene Glycol). Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2002, 203, 2674–2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuels, R.J. Solid-state Characterization of the Structure and Deformation Behavior of Water-soluble Hydroxypropylcellulose. J. Polym. Sci. Part A-2 Polym. Phys. 1969, 7, 1197–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinkert, A.; Marsh, K.N.; Pang, S.; Staiger, M.P. Ionic Liquids and Their Interaction with Cellulose. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 6712–6728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrmann, D.; Danzer, A.; Sadowski, G. Water Sorption in Glassy Polyvinylpyrrolidone-Based Polymers. Membranes 2022, 12, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunauer, S.; Emmett, P.H.; Teller, E. Adsorption of Gases in Multimolecular Layers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1938, 60, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zografi, G.; Kontny, M.J. The Interactions of Water with Cellulose- and Starch-Derived Pharmaceutical Excipients. Pharm. Res. An Off. J. Am. Assoc. Pharm. Sci. 1986, 3, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Zografi, G. The Relationship between “BET” and “Free Volume”-derived Parameters for Water Vapor Absorption into Amorphous Solids. J. Pharm. Sci. 2000, 89, 1063–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamaura, T.; Newton, J.M. Interaction between Water and Poly(Vinylpyrrolidone) Containing Polyethylene Glycol. J. Pharm. Sci. 1999, 88, 1228–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambroz, F.; Macdonald, T.J.; Martis, V.; Parkin, I.P. Evaluation of the BET Theory for the Characterization of Meso and Microporous MOFs. Small Methods 2018, 2, 201800173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tordi, P.; Tamayo, A.; Jeong, Y.; Han, B.; Al Kayal, T.; Cavallo, A.; Bonini, M.; Samorì, P. Fully Bio-Based Gelatin Organohydrogels via Enzymatic Crosslinking for Sustainable Soft Strain and Temperature Sensing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, e20762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tordi, P.; Ridi, F.; Samorì, P.; Bonini, M. Cation-Alginate Complexes and Their Hydrogels: A Powerful Toolkit for the Development of Next-Generation Sustainable Functional Materials. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2416390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, R.; Gérard, E.; Dugand, P.; Rempp, P.; Gnanou, Y. Rheological Characterization of the Gel Point: A New Interpretation. Macromolecules 1991, 24, 1321–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, E.P. Viscoelastic Windows of Pressure-Sensitive Adhesives. J. Adhes. 1991, 34, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlasova, A.V.; Smirnova, N.M.; Melekhina, V.Y.; Antonov, S.V.; Ilyin, S.O. Effect of Relaxation Properties on the Bonding Durability of Polyisobutylene Pressure-Sensitive Adhesives. Polymers 2025, 17, 2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos, A.; Creton, C.; Novikov, M.B.; Feldstein, M.M. Viscoelasticity and Tack of Poly(Vinyl Pyrrolidone)-Poly(Ethylene Glycol) Blends. J. Polym. Sci. Part B Polym. Phys. 2002, 40, 2395–2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, J.; Barkat, K.; Ashraf, M.U.; Badshah, S.F.; Ahmad, Z.; Anjum, I.; Shabbir, M.; Mehmood, Y.; Khalid, I.; Malik, N.S.; et al. Preparation and Characterization of Polymeric Cross-Linked Hydrogel Patch for Topical Delivery of Gentamicin. e-Polymers 2023, 23, 20230045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldstein, M.M. Contribution of Relaxation Processes to Adhesive-Joint Strength of Viscoelastic Polymers. Polym. Sci. Ser. A 2009, 51, 1341–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | PVP/PEG at a Ratio of 2:1 (wt%) | HPC (wt%) |

|---|---|---|

| P1 | 100 | 0 |

| P1-H3 | 97 | 3 |

| P1-H6 | 94 | 6 |

| P1-H9 | 91 | 9 |

| P1-H12 | 88 | 12 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Karabanova, A.B.; Ilyin, S.O.; Vlasova, A.V.; Antonov, S.V. Rheology and Moisture-Responsive Adhesion of Hydroxypropyl Cellulose-Enhanced Polyvinylpyrrolidone–Polyethylene Glycol Hydrogels. Gels 2025, 11, 974. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120974

Karabanova AB, Ilyin SO, Vlasova AV, Antonov SV. Rheology and Moisture-Responsive Adhesion of Hydroxypropyl Cellulose-Enhanced Polyvinylpyrrolidone–Polyethylene Glycol Hydrogels. Gels. 2025; 11(12):974. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120974

Chicago/Turabian StyleKarabanova, Anna Borisovna, Sergey Olegovich Ilyin, Anna Vladimirovna Vlasova, and Sergey Vyacheslavovich Antonov. 2025. "Rheology and Moisture-Responsive Adhesion of Hydroxypropyl Cellulose-Enhanced Polyvinylpyrrolidone–Polyethylene Glycol Hydrogels" Gels 11, no. 12: 974. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120974

APA StyleKarabanova, A. B., Ilyin, S. O., Vlasova, A. V., & Antonov, S. V. (2025). Rheology and Moisture-Responsive Adhesion of Hydroxypropyl Cellulose-Enhanced Polyvinylpyrrolidone–Polyethylene Glycol Hydrogels. Gels, 11(12), 974. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120974

.png)