Formulation and Evaluation of Different Nanogels of Tapinarof for Treatment of Psoriasis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

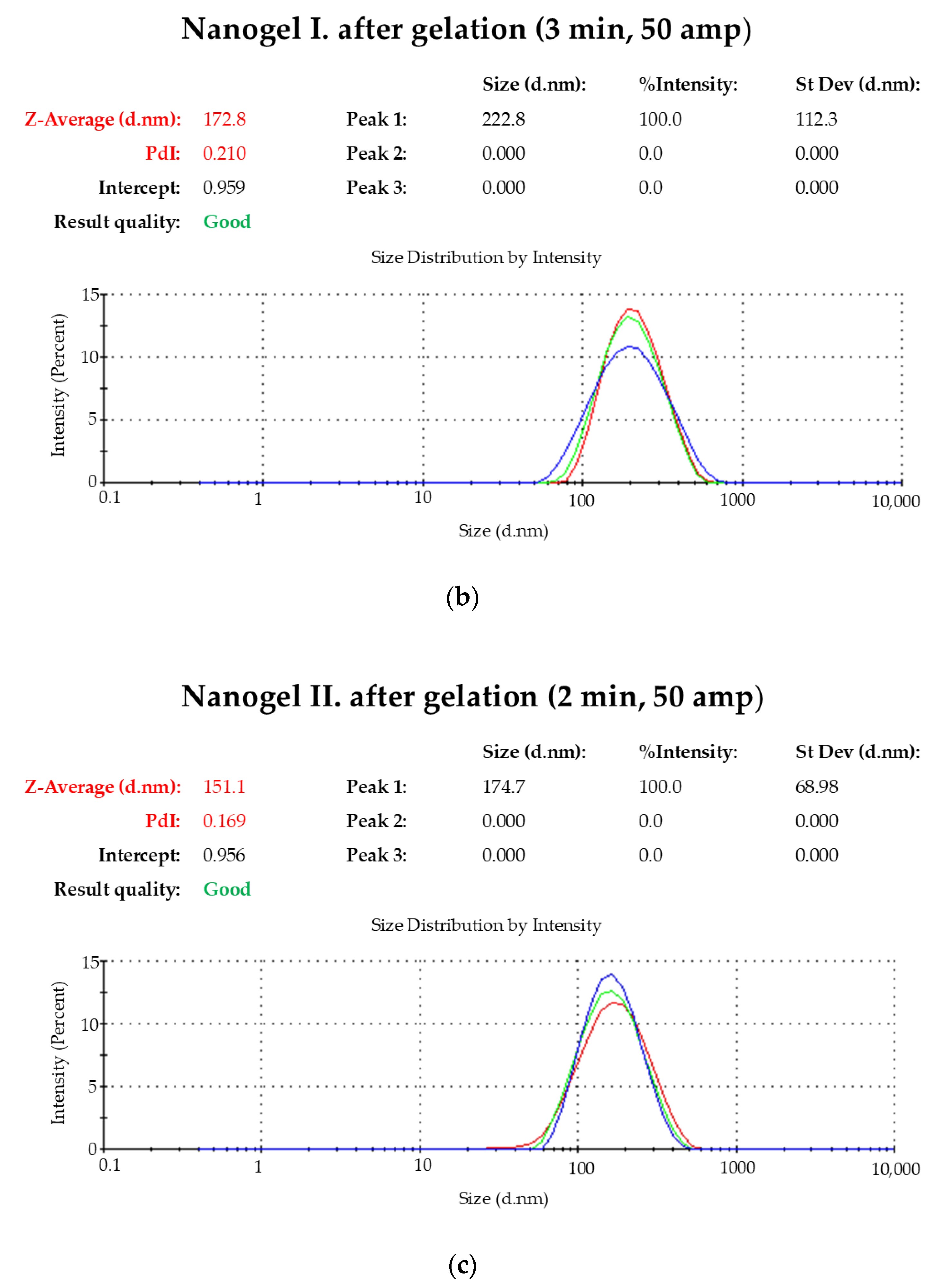

2.1. Droplet Size Distribution

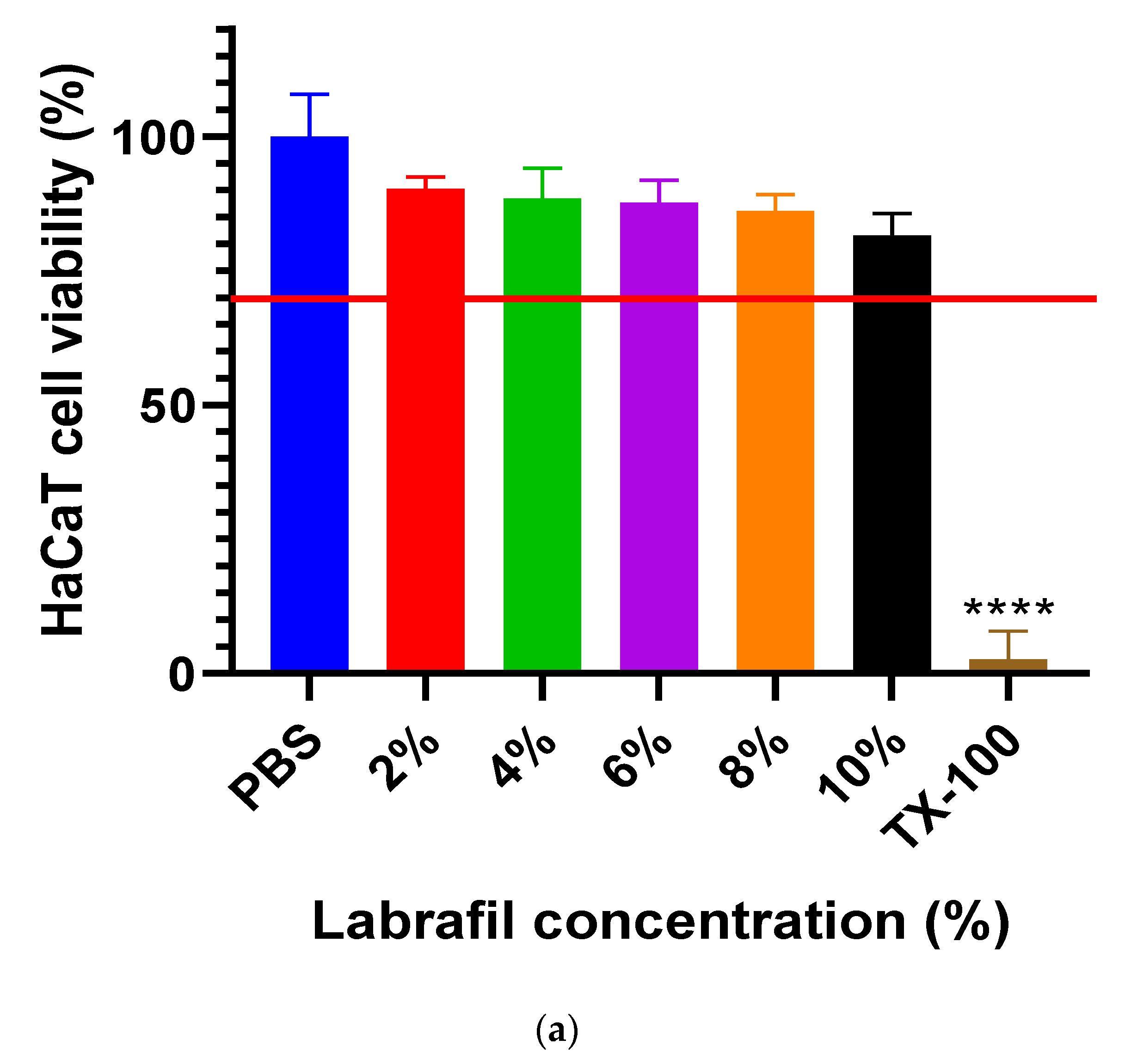

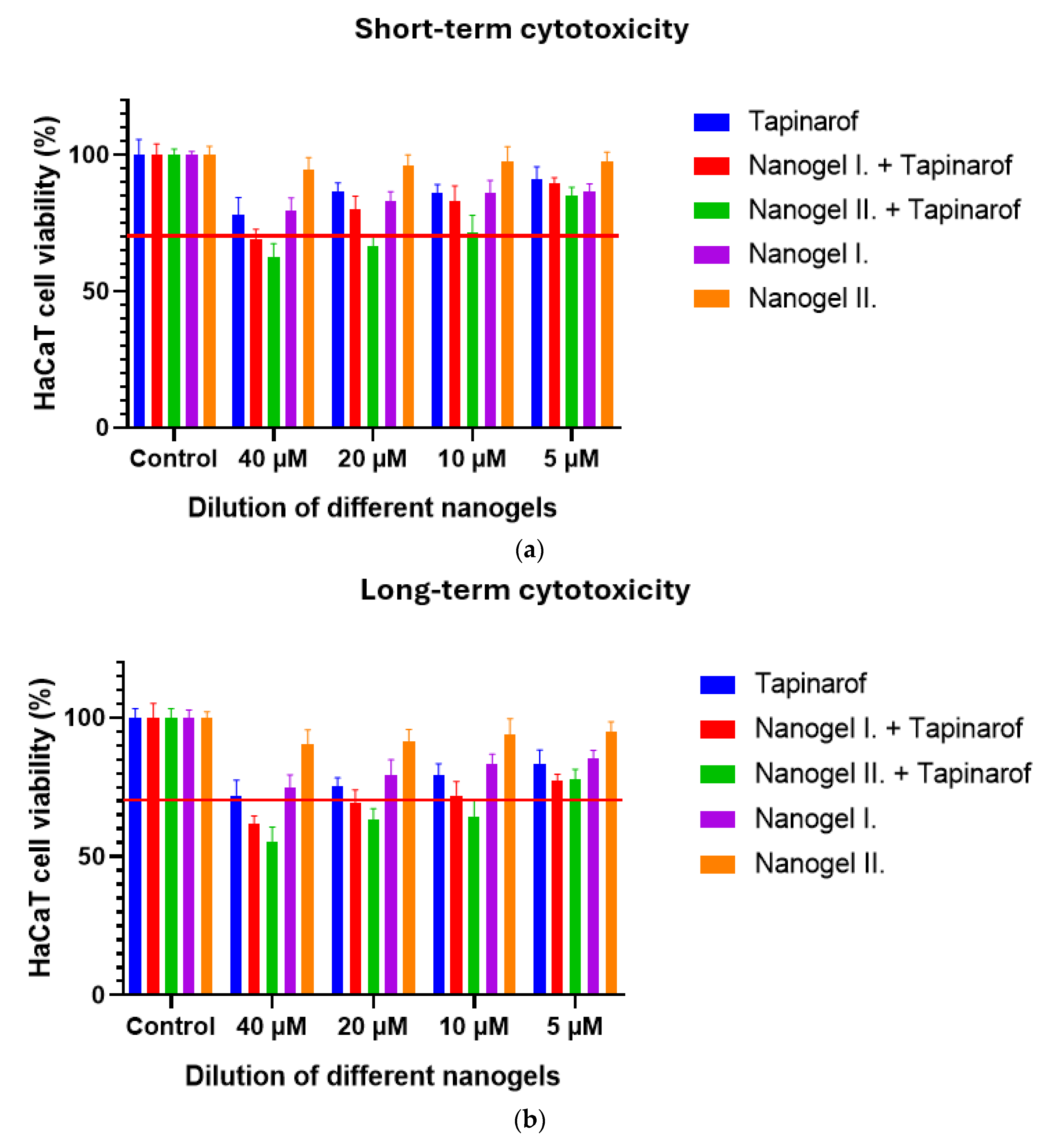

2.2. Cell Viability Study

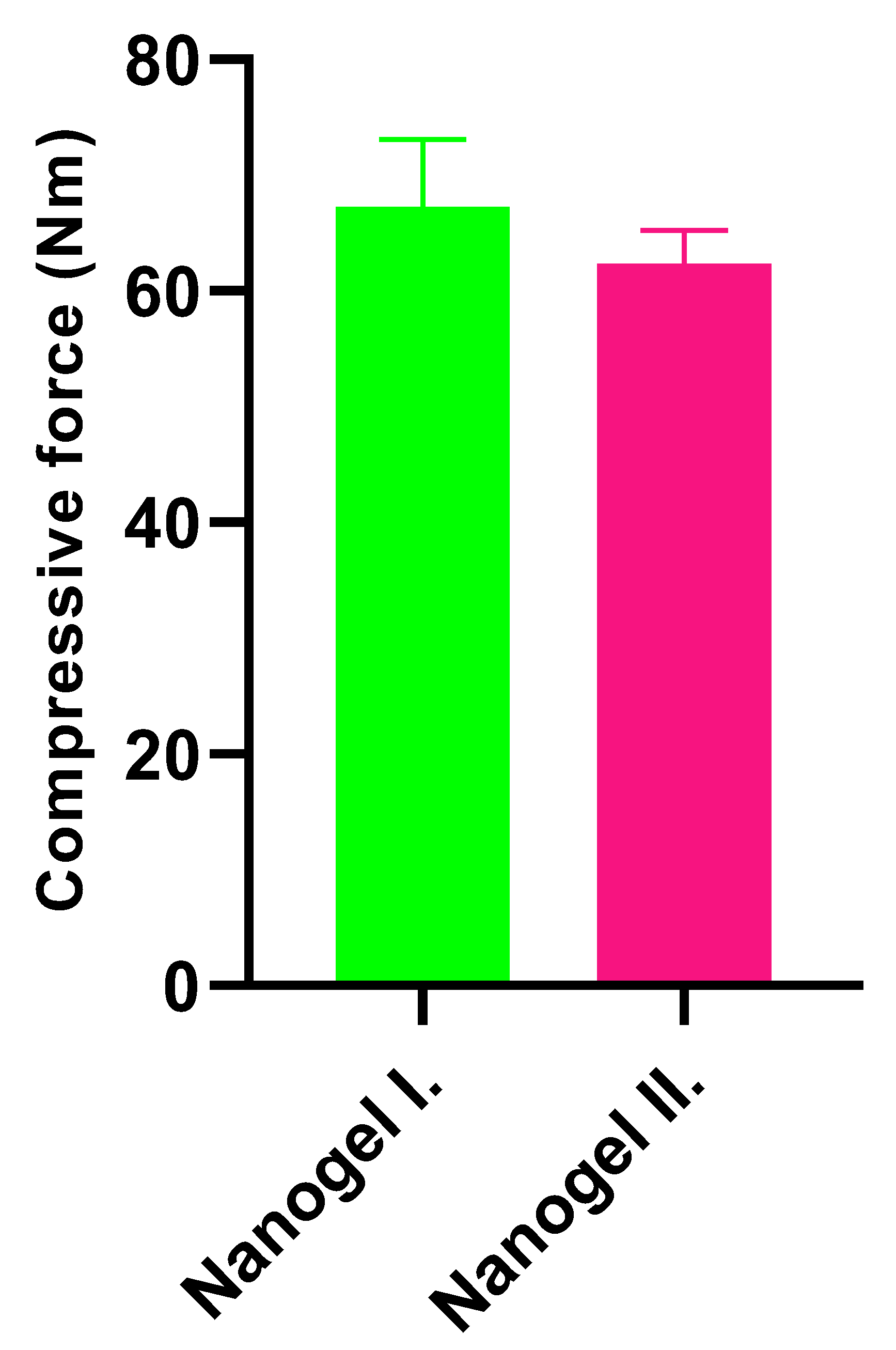

2.3. Texture Analysis

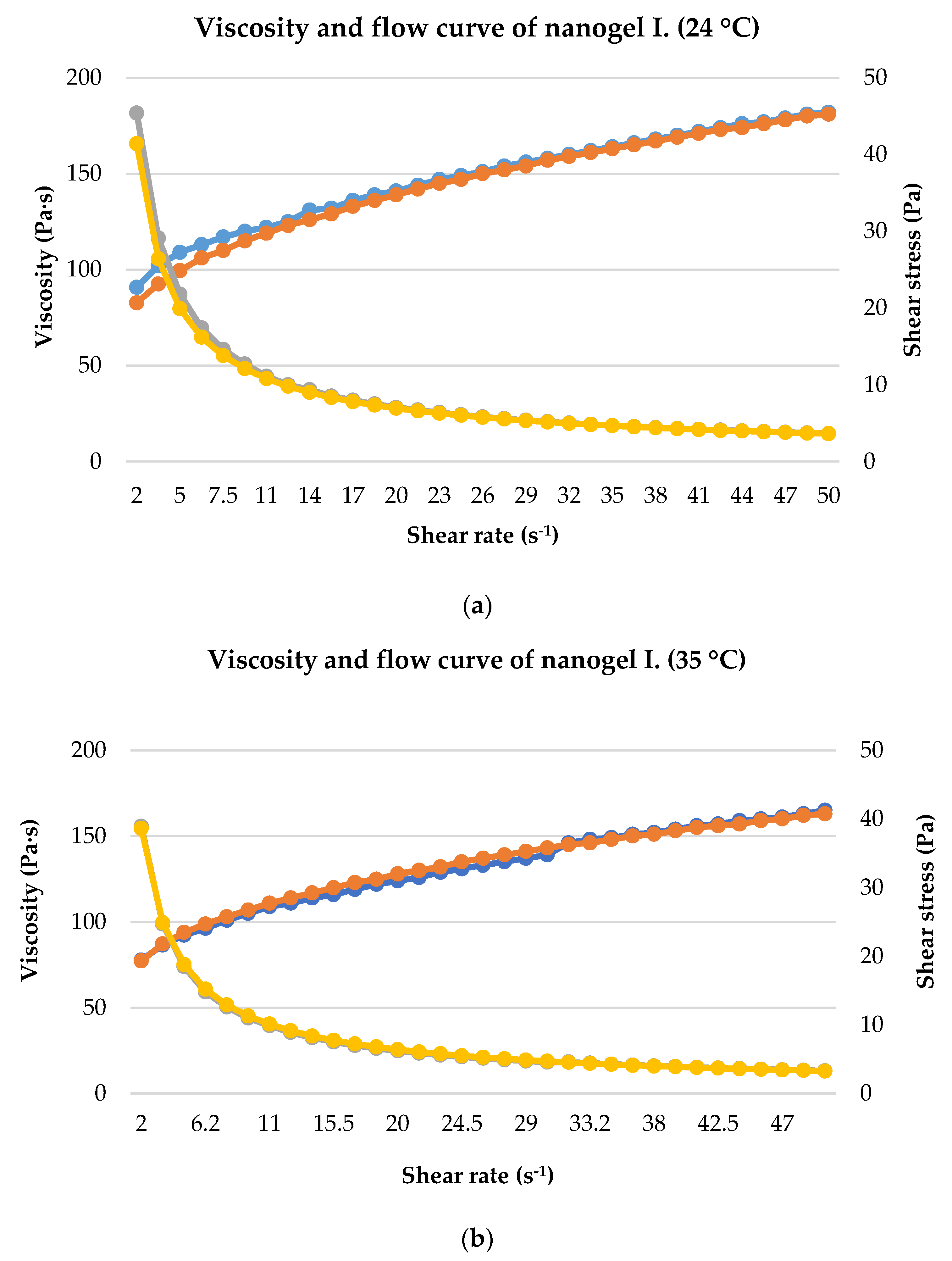

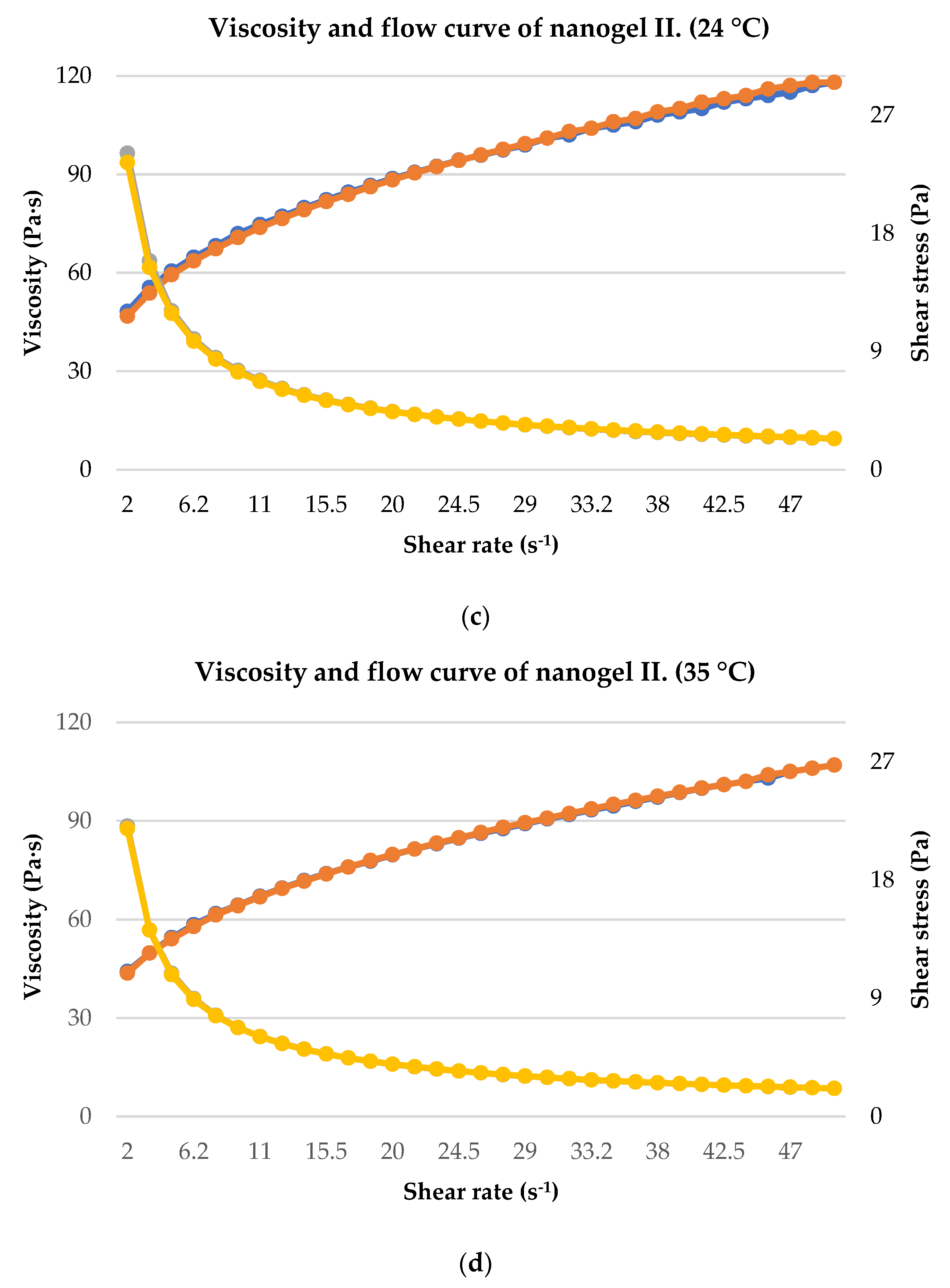

2.4. Rheological Analysis

2.5. In Vitro Wound Healing Assay

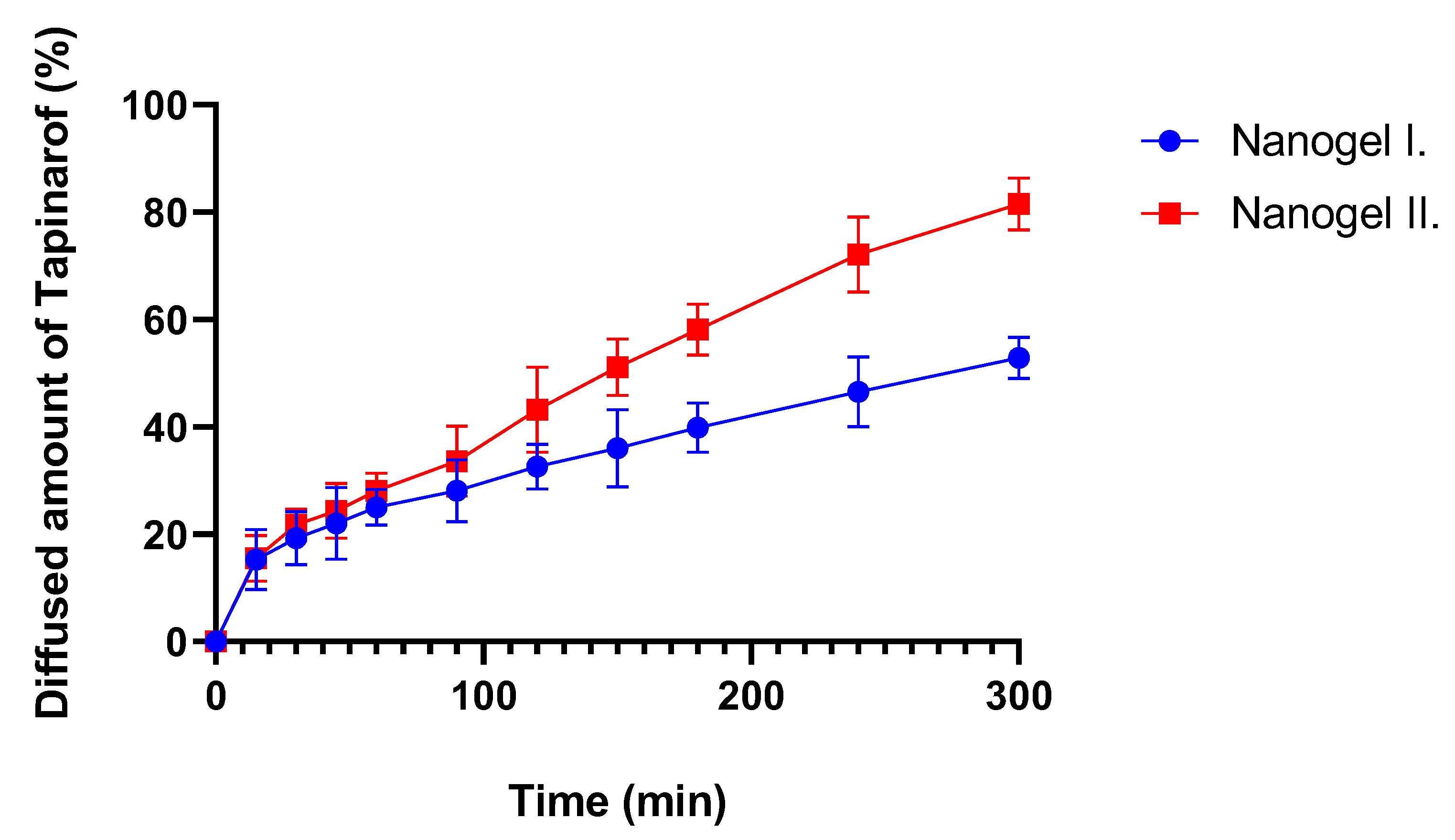

2.6. In Vitro Release Study

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Preparation of Nanogels

4.3. Droplet Size Distribution

4.4. Cell Viability Study

4.5. Texture Analysis

4.6. Rheological Analysis

4.7. In Vitro Wound Healing Assay

4.8. In Vitro Release Study

4.9. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nogueira, S.; Rodrigues, M.A.; Vender, R.; Torres, T. Tapinarof for the Treatment of Psoriasis. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 35, e15931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugumaran, D.; Chee, A.; Yong, H.; Stanslas, J. Advances in Psoriasis Research: From Pathogenesis to Therapeutics. Life Sci. 2024, 355, 122991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lé, A.M.; Torres, T. New Topical Therapies for Psoriasis. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2022, 23, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bissonnette, R.; Stein Gold, L.; Rubenstein, D.S.; Tallman, A.M.; Armstrong, A. Tapinarof in the Treatment of Psoriasis: A Review of the Unique Mechanism of Action of a Novel Therapeutic Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor–Modulating Agent. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2021, 84, 1059–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieminska, I.; Pieniawska, M.; Grzywa, T.M. The Immunology of Psoriasis—Current Concepts in Pathogenesis. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2024, 66, 164–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, A.W.; Siegel, M.P.; Bagel, J.; Boh, E.E.; Buell, M.; Cooper, K.D.; Duffin, C.; Eichenfield, L.F.; Garg, A.; Gelfand, J.M.; et al. From the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation: Treatment Targets for Plaque Psoriasis. J. Am. Dermatol. 2017, 76, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurel, P.; Bahadur, S.; Bajpai, M. Treatment of Chronic Plaque Psoriasis: An Overview on Current Update. Pharmacol. Res. Rep. 2024, 2, 100004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.T.; Kelly, K.A.; Feldman, S.R. An Overview of Benvitimod for the Treatment of Psoriasis: A Narrative Review. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2022, 23, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.; Zhang, G.; Xia, Z.; Chen, N.; Yang, S.; Li, L. Identification of Triazolopyridine Derivatives as a New Class of AhR Agonists and Evaluation of Anti-Psoriasis Effect in a Mouse Model. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 231, 114122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossmann, M.C.; Pixley, J.N.; Feldman, S.R. A Review of Topical Tapinarof for the Treatment of Plaque Psoriasis. Ann. Pharmacother. 2024, 58, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keam, S.J. Tapinarof Cream 1%: First Approval. Drugs 2022, 82, 1221–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmona-Rocha, E.; Rusiñol, L.; Puig, L. New and Emerging Oral/Topical Small-Molecule Treatments for Psoriasis. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silverberg, J.I.; Nelson, D.B.; Yosipovitch, G. Addressing Treatment Challenges in Atopic Dermatitis with Novel Topical Therapies. J. Dermatolog. Treat. 2016, 27, 568–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, S.H.; Jayawickreme, C.; Rickard, D.J.; Nicodeme, E.; Bui, T.; Simmons, C.; Coquery, C.M.; Neil, J.; Pryor, W.M.; Mayhew, D.; et al. Tapinarof Is a Natural AhR Agonist That Resolves Skin Inflammation in Mice and Humans. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2017, 137, 2110–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Meng, X.; Lin, J. The Role of Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor in the Pathogenesis and Treatment of Psoriasis. J. Cutan. Med. Surg. 2024, 28, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, G.; Dhawan, B.; Harikumar, S. Enhanced Transdermal Permeability of Piroxicam through Novel Nanoemulgel Formulation. Int. J. Pharm. Investig. 2014, 4, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botha, N.L.; Mushonga, P.; Onani, M.O. Review on Nanogels and Their Applications on Dermal Therapy. Polym. Polym. Compos. 2023, 31, 09673911231192816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Hu, B.; Yuan, X.; Cai, L.; Gao, H. Nanogel: A Versatile Nano-Delivery System for Biomedical Applications. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siafaka, P.I.; Bülbül, E.Ö.; Okur, M.E.; Karantas, I.D. The Application of Nanogels as Efficient Drug Delivery Platforms for Dermal/Transdermal Delivery. Gels 2023, 9, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vtama Cream for Psoriasis: Dosage, Side Effects & More Drugs.Com. Available online: https://www.drugs.com/vtama.html (accessed on 5 September 2024).

- Alam, M.S.; Algahtani, M.S.; Ahmad, J.; Kohli, K.; Shafiq-Un-Nabi, S.; Warsi, M.H.; Ahmad, M.Z. Formulation Design and Evaluation of Aceclofenac Nanogel for Topical Application. Ther. Deliv. 2020, 11, 767–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, M.; Saha, S.N.; Akram, T. Nanogels Based Drug Delivery System: A Promising Therapeutic Strategy Nanogels Based Drug Delivery System: A Promising Therapeutic Strategy. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. 2023, 1, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, R.; Ahmed, N.; Ullah, N.; Khan, M.I.; Elaissari, A.; Rehman, A. Biodegradable Ingredient-Based Emulgel Loaded with Ketoprofen Nanoparticles. AAPS Pharmscitech 2018, 19, 1869–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mechanistic, K.; Study, R. Ibuprofen-Loaded Chitosan–Lipid Nanoconjugate Hydrogel with Gum Arabic: Green Synthesis, Characterisation, In Vitro Kinetics Mechanistic Release Study and PGE2 Production Test. Gels 2021, 7, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitro, I.; Vivo, E.; Evaluation, I.V.; Algahtani, M.S.; Ahmad, M.Z.; Nourein, I.H.; Albarqi, H.A.; Alyami, H.S.; Alyami, M.H.; Alqahtani, A.A.; et al. Preparation and Characterization of Curcumin Nanoemulgel Utilizing Ultrasonication Technique for Wound Healing. Gels 2021, 7, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lines, N.C.; Roberts, M.S.; Grice, J.E. In vitro screening of topical formulation excipients for epithelial toxicity in cancerous and non-cancerous cell lines. EXCLI J. 2023, 22, 1173. [Google Scholar]

- Maupas, C.; Moulari, B.; Béduneau, A.; Lamprecht, A.; Pellequer, Y. Surfactant Dependent Toxicity of Lipid Nanocapsules in HaCaT Cells. Int. J. Pharm. 2011, 411, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, K.; Josef Schmolz, J.; Hoang, F.; Wolf, H.; Seiser, S.; Elbe-Bürger, A.; Klang, V. Surfactants for Stabilization of Dermal Emulsions and Their Skin Compatibility under UVA Irradiation: Diacyl Phospholipids and Polysorbate 80 Result in High Viability Rates of Primary Human Skin Cells. Int. J. Pharm. 2024, 653, 123903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, M.T.; Silva, A.C.G.; Nascimento, T.L.; Diniz, D.G.A.; Valadares, M.C.; Lima, E.M. Protective Effect of Sucupira Oil Nanoemulsion against Oxidative Stress in UVA-Irradiated HaCaT Cells. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2019, 71, 1532–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Gao, J.; Zheng, H.; Zhang, R.; Han, Y. The Preparation of 3,5-Dihydroxy-4-Isopropylstilbene Nanoemulsion and in Vitro Release. Int. J. Nanomed. 2011, 6, 649–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Musakhanian, J.; Osborne, D.W.; David, J. Skin Penetration and Permeation Properties of—Transcutol® in Complex Formulations. AAPS PharmSciTech 2024, 25, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walicka, A.; Falicki, J.; Iwanowska-Chomiak, B. Rheology of Drugs for Topical and Transdermal Delivery. Int. J. Appl. Mech. Eng. 2019, 24, 179–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ay Şenyiğit, Z.; Coşkunmeriç, N.; Çağlar, E.Ş.; Öztürk, İ.; Atlıhan Gündoğdu, E.; Siafaka, P.I.; Üstündağ Okur, N. Chitosan-Bovine Serum Albumin-Carbopol 940 Nanogels for Mupirocin Dermal Delivery: Ex-Vivo Permeation and Evaluation of Cellular Binding Capacity via Radiolabeling. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 2021, 26, 852–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajinikanth, P.S.; Chellian, J. Development and Evaluation of Nanostructured Lipid Carrier-Based Hydrogel for Topical Delivery of 5-Fluorouracil. Int. J. Nanomed. 2016, 11, 5067–5077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giuseppe, E.; Corbi, F.; Funiciello, F.; Massmeyer, A.; Santimano, T.N.; Rosenau, M.; Davaille, A. Characterization of Carbopol® Hydrogel Rheology for Experimental Tectonics and Geodynamics. Tectonophysics 2015, 642, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.-Q.; Liu, P.; Zhang, J.-Z. Anti-Inammatory Effects of AhR Agonist Benvitimod in TNFα/IFNγ Stimulated HaCaT Cells and Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells from Patients with Atopic Dermatitis. Preprint 2022, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Zeng, Y.; Shi, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, H.; Wang, W. Benvitimod Inhibits MCM6-Meditated Proliferation of Keratinocytes by Regulating the JAK/STAT3 Pathway. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2023, 109, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinka, D.; Doma, E.; Szendi, N.; Páll, J.; Kósa, D.; Pető, Á.; Fehér, P.; Ujhelyi, Z.; Fenyvesi, F.; Váradi, J.; et al. Formulation, Characterization and Permeability Studies of Fenugreek (Trigonella Foenum-Graecum) Containing Self-Emulsifying Drug Delivery System (SEDDS). Molecules 2022, 27, 2846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pető, Á.; Kósa, D.; Haimhoffer, Á.; Nemes, D.; Fehér, P.; Ujhelyi, Z.; Vecsernyés, M.; Váradi, J.; Fenyvesi, F.; Frum, A.; et al. Topical Dosage Formulation of Lyophilized Philadelphus Coronarius L. Leaf and Flower: Antimicrobial, Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Assessment of the Plant. Molecules 2022, 27, 2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavra, D.I.; Endres, L.; Pető, Á.; Józsa, L.; Fehér, P.; Ujhelyi, Z.; Pallag, A.; Marian, E.; Vicas, L.G.; Ghitea, T.C.; et al. In Vitro and Human Pilot Studies of Different Topical Formulations Containing Rosa Species for the Treatment of Psoriasis. Molecules 2022, 27, 5499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pető, Á.; Kósa, D.; Haimhoffer, Á.; Fehér, P.; Ujhelyi, Z.; Sinka, D.; Fenyvesi, F.; Váradi, J.; Vecsernyés, M.; Gyöngyösi, A.; et al. Nicotinic Amidoxime Derivate Bgp-15, Topical Dosage Formulation and Anti-Inflammatory Effect. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bácskay, I.; Hosszú, Z.; Budai, I.; Ujhelyi, Z.; Fehér, P.; Kósa, D.; Haimhoffer, Á.; Pető, Á. Formulation and Evaluation of Transdermal Patches Containing BGP-15. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Józsa, L.; Ujhelyi, Z.; Vasvári, G.; Sinka, D.; Nemes, D.; Fenyvesi, F.; Váradi, J.; Vecsernyés, M.; Szabó, J.; Kalló, G.; et al. Formulation of Creams Containing Spirulina Platensis Powder with Different Nonionic Surfactants for the Treatment of Acne Vulgaris. Molecules 2020, 25, 4856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frei, G.; Haimhoffer, Á.; Csapó, E.; Bodnár, K.; Vasvári, G.; Nemes, D.; Lekli, I.; Gyöngyösi, A.; Bácskay, I.; Fehér, P.; et al. In Vitro and In Vivo Efficacy of Topical Dosage Forms Containing Self-Nanoemulsifying Drug Delivery System Loaded with Curcumin. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szliszka, E.; Czuba, Z.P.; Domino, M.; Mazur, B.; Zydowicz, G.; Krol, W. Ethanolic Extract of Propolis (EEP) Enhances the Apoptosis- Inducing Potential of TRAIL in Cancer Cells. Molecules 2009, 14, 738–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argenziano, M.; Haimhoffer, A.; Bastiancich, C.; Jicsinszky, L.; Caldera, F.; Trotta, F.; Scutera, S.; Alotto, D.; Fumagalli, M.; Musso, T.; et al. In Vitro Enhanced Skin Permeation and Retention of Imiquimod Loaded in β-Cyclodextrin Nanosponge Hydrogel. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Time (min) | Amp (%) | Z-Average (d/nm) | PdI |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 50 | 275.6 | 0.282 |

| 3 | 50 | 172.8 | 0.210 |

| Time (min) | Amp (%) | Z-Average (d/nm) | PdI |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 50 | 151.1 | 0.169 |

| Kinetic Model | ||

|---|---|---|

| Composition | Zero | First |

| Nanogel I. | 0.9892 | 0.978 |

| Nanogel II. | 0.994 | 0.998 |

| Composition | SNEDDS I. | SNEDDS II. |

|---|---|---|

| Labrafil | 6% | - |

| Triacetin | 3% | - |

| Tween 80 | 5% | 8.75% |

| Transcutol HP | 15% | - |

| Ethanol | 5% | 26.25% |

| Kolliphor | 5% | - |

| PEG 400 | 5% | - |

| Oleic acid | - | 10% |

| Purified water | 56% | 55% |

| Composition | Nanogel I. | Nanogel-Tap I. | Nanogel II. | Nanogel-Tap II. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tapinarof | - | 1% | - | 1% |

| SNEDDS | 33.3% | 33.3% | 50% | 50% |

| Glycerin | 5% | 5% | 15% | - |

| Carbopol 940 | 0.5% | 0.5% | 5% | - |

| Carbopol 934 | - | - | 0.5% | 0.5% |

| Model | Equations | Graphic |

|---|---|---|

| Zero-order | Qt = Q0 + k0t | The graphic of the drug-dissolved fraction versus time is linear. |

| First-order | The graphic of the decimal logarithm of the released amount of drug versus time is linear. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Balogh, B.; Pető, Á.; Haimhoffer, Á.; Sinka, D.; Kósa, D.; Fehér, P.; Ujhelyi, Z.; Argenziano, M.; Cavalli, R.; Bácskay, I. Formulation and Evaluation of Different Nanogels of Tapinarof for Treatment of Psoriasis. Gels 2024, 10, 675. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels10110675

Balogh B, Pető Á, Haimhoffer Á, Sinka D, Kósa D, Fehér P, Ujhelyi Z, Argenziano M, Cavalli R, Bácskay I. Formulation and Evaluation of Different Nanogels of Tapinarof for Treatment of Psoriasis. Gels. 2024; 10(11):675. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels10110675

Chicago/Turabian StyleBalogh, Barbara, Ágota Pető, Ádám Haimhoffer, Dávid Sinka, Dóra Kósa, Pálma Fehér, Zoltán Ujhelyi, Monica Argenziano, Roberta Cavalli, and Ildikó Bácskay. 2024. "Formulation and Evaluation of Different Nanogels of Tapinarof for Treatment of Psoriasis" Gels 10, no. 11: 675. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels10110675

APA StyleBalogh, B., Pető, Á., Haimhoffer, Á., Sinka, D., Kósa, D., Fehér, P., Ujhelyi, Z., Argenziano, M., Cavalli, R., & Bácskay, I. (2024). Formulation and Evaluation of Different Nanogels of Tapinarof for Treatment of Psoriasis. Gels, 10(11), 675. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels10110675