Food Gels of Fish Protein Isolate from Atlantic Cod (Gadus morhua) By-Products Recovered by pH Shift

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Yield and Chemical Composition of Fish Protein Isolates

2.2. Functional Properties of Fish Protein Isolates

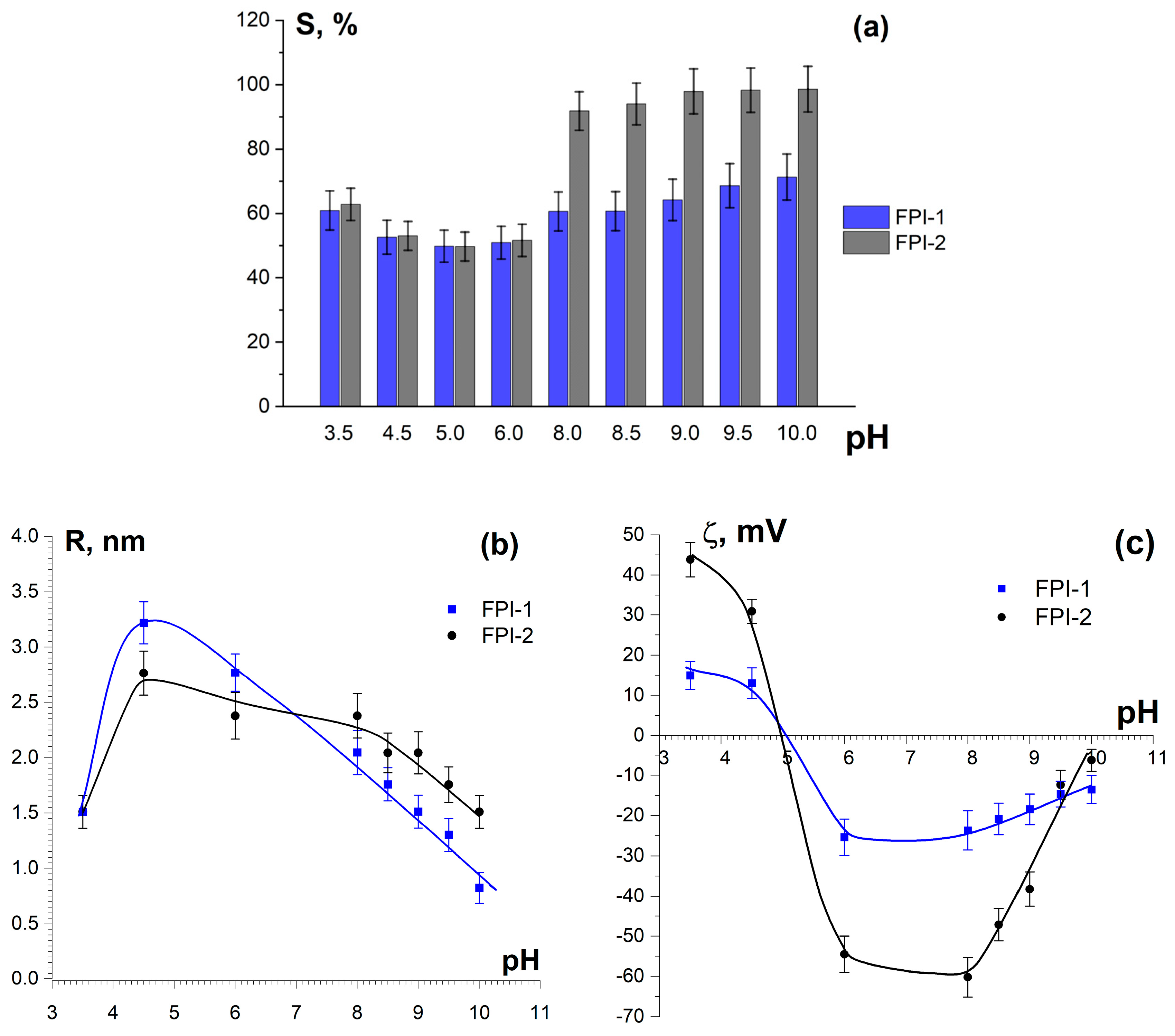

2.2.1. Solubility and Zeta Potential

2.2.2. Water Holding Capacity, Fat Holding Capacity, and Emulsifying Ability

2.3. Physicochemical Properties of Fish Protein Isolates

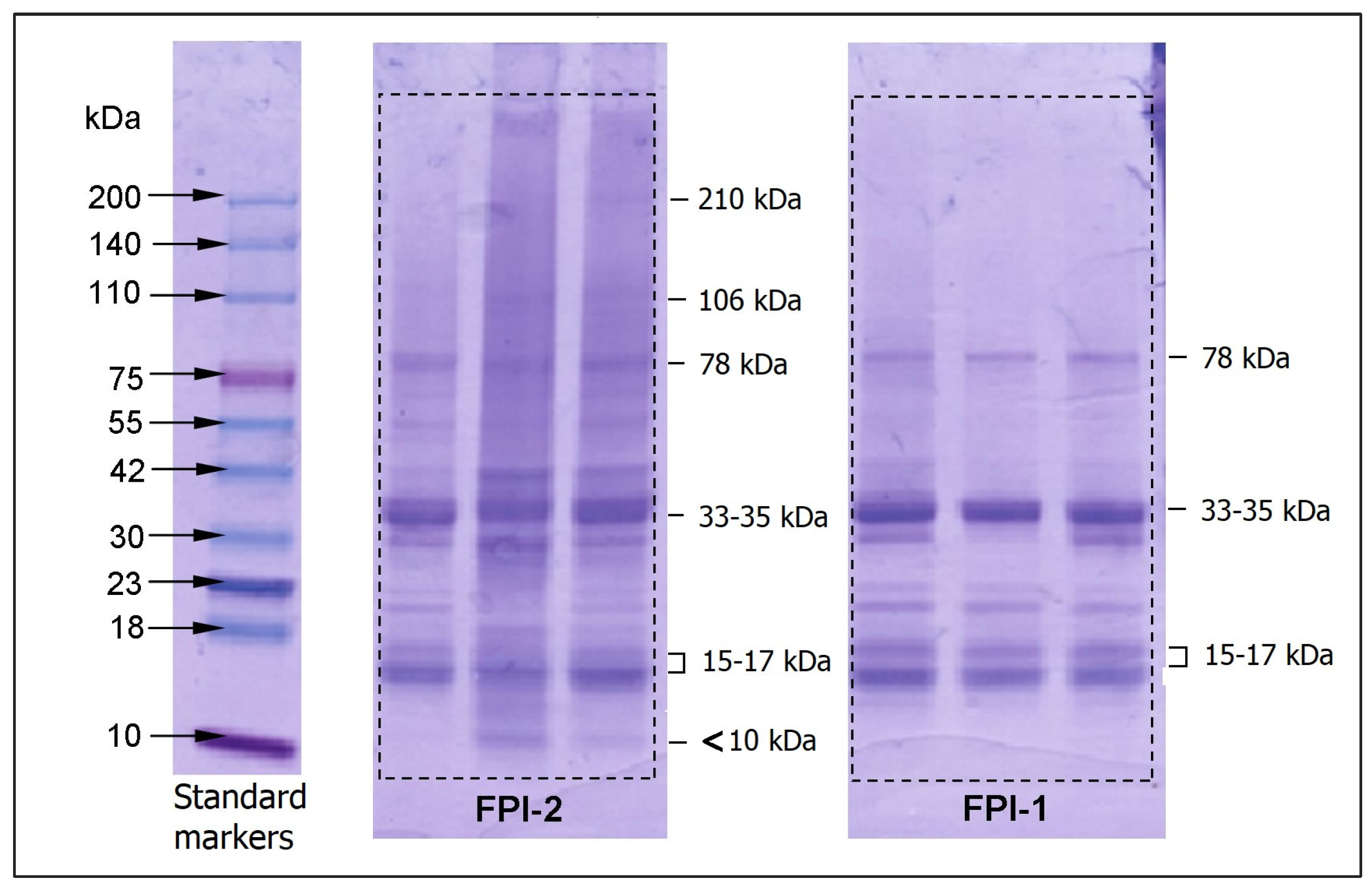

2.3.1. Molecular Weight Composition

2.3.2. Amino Acid Composition

| Amino Acids | Cod Muscle Tissue [48] | FPI-1 | FPI-2 | FAO/WHO/UNU Standards for Adults (g/100 g Protein) [46] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glycine | 4.7 ± 0.1 a | 3.7 ± 0.1 b | 3.6 ± 0.3 b | |

| Proline | 3.7 ± 0.3 a | 2.3 ± 0.5 b | 2.4 ± 0.6 **b | |

| Aspartic acid | 7.9 ± 1.3 a | 9.1 ± 0.2 b | 9.2 ± 1.1 b | |

| Glutamic acid | 17.8 ± 1.5 a | 17.6 ± 0.6 a | 15.5 ± 1.5 b | |

| Serine | 4.9 ± 0.2 a | 4.0 ± 0.2 b | 3.5 ± 0.4 c | |

| Histidine | 2.0 ± 0.1 a | 5.3 ± 0.2 b | 6.3 ± 0.4 c | 1.5 |

| Threonine * | 4.7 ± 0.1 a | 4.1 ± 0.1 b | 3.5 ± 0.4 c | 2.3 |

| Arginine | 7.2 ± 0.4 a | 7.3 ± 0.2 a | 8.4 ± 0.3 b | |

| Alanine | 6.4 ± 0.3 a | 5.2 ± 0.1 b | 5.3 ± 0.4 b | |

| Tyrosine | 4.0 ± 0.2 a | 6.1 ± 0.3 b | 7.0 ± 0.5 c | 3.8 |

| Valine * | 4.8 ± 0.2 a | 6.6 ± 0.1 b | 7.2 ± 0.4 c | 3.9 |

| Methionine * | 3.0 ± 0.2 a | 1.5 ± 0.2 b | 1.5 ± 0.1 b | 2.2 |

| Leucine * | 8.9 ± 0.3 a | 14.4 ± 0.4 b | 14.4 ± 0.5 b | 5.9 |

| Isoleucine * | 4.2 ± 0.2 a | 3.9 ± 0.1 a | 4.0 ± 0.2 a | 3.0 |

| Lysine * | 10.2 ± 0.5 a | 8.0 ± 2.6 b | 7.8 ± 2.7 **b | 4.5 |

| Phenylalanine * | 4.2 ± 0.2 a | 3.4 ± 0.1b | 3.4 ± 0.2 b | 3.8 |

| ∑ * (EAA) | 40.0 ± 0.7 | 41.9 ± 2.6 a | 41.8 ± 2.7 |

2.4. Characteristics of Heat-Induced Hydrogels from Fish Protein Isolate

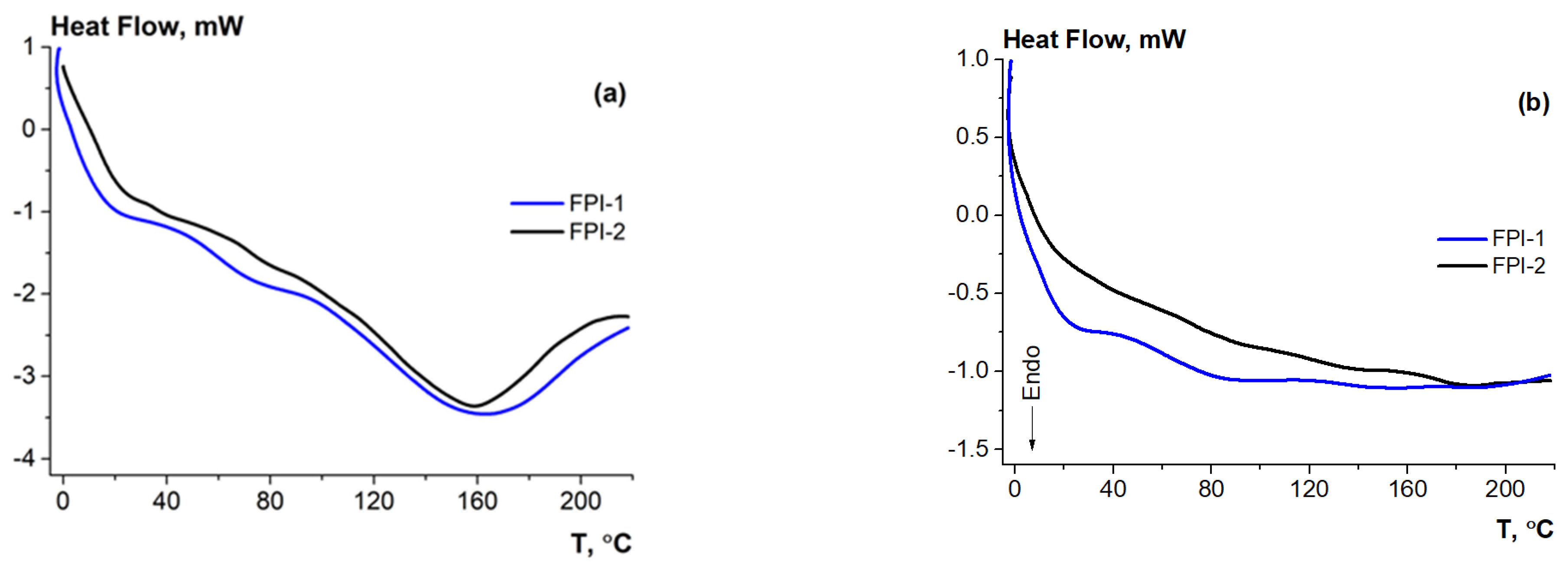

2.4.1. Thermal Analysis

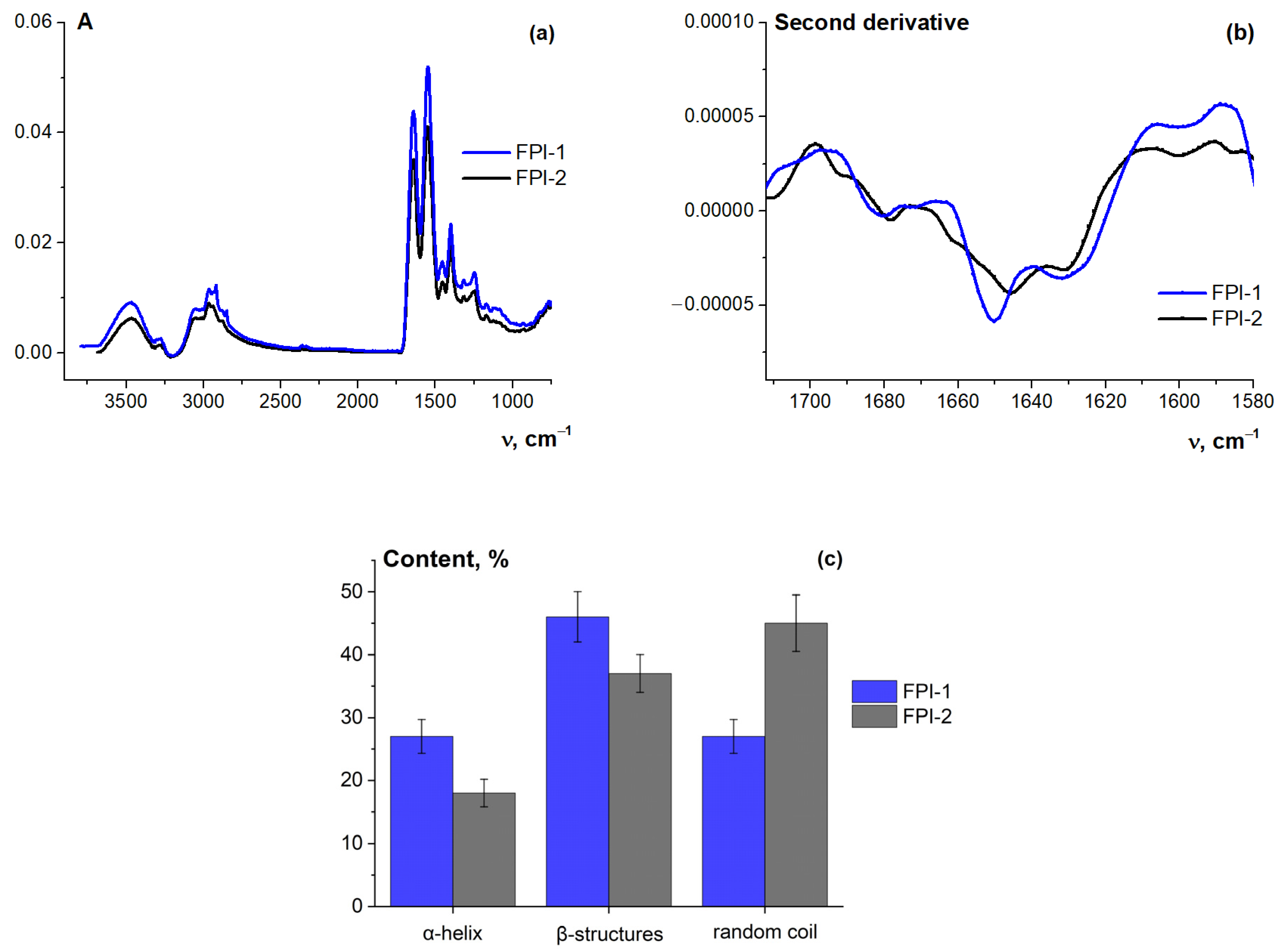

2.4.2. Protein Secondary Structure from FT-IR Spectra

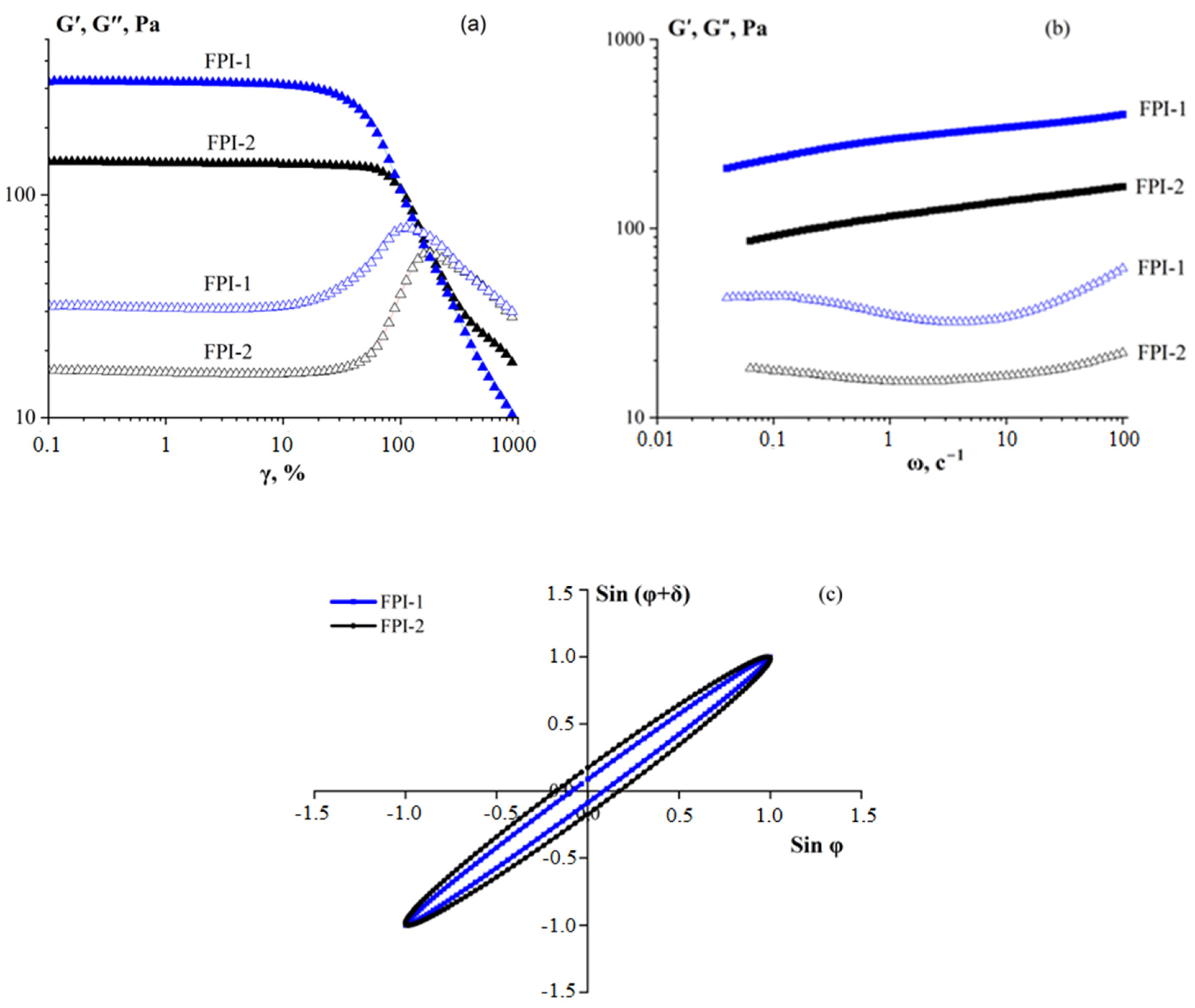

2.4.3. Rheological Behaviour

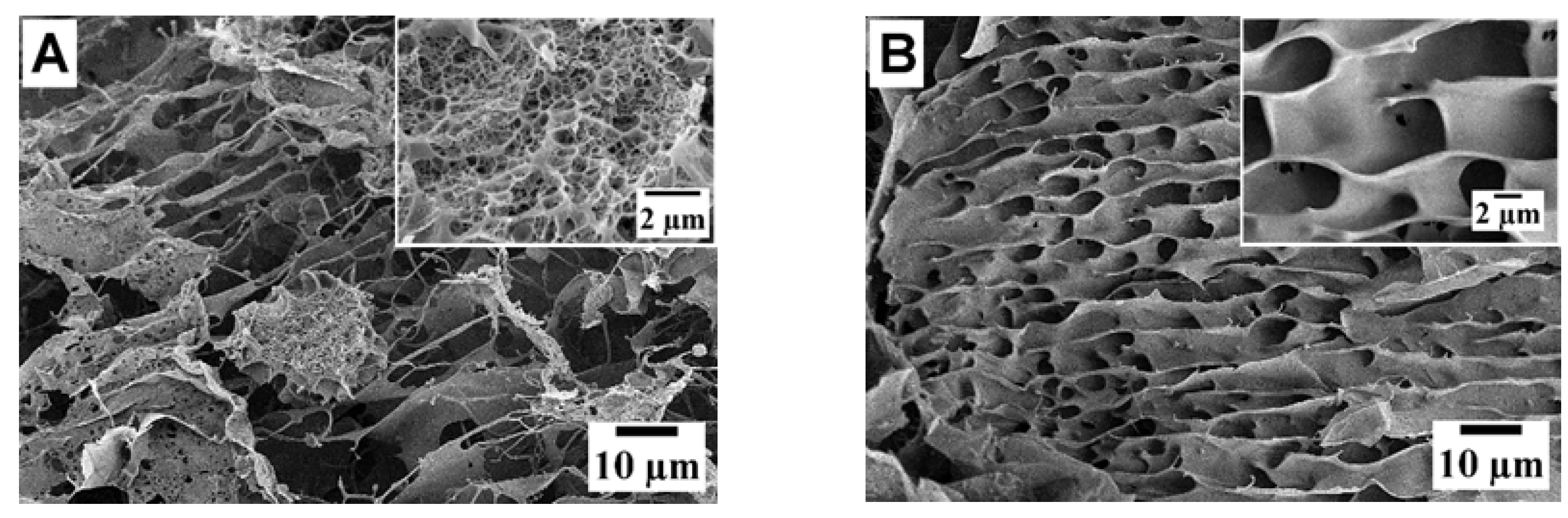

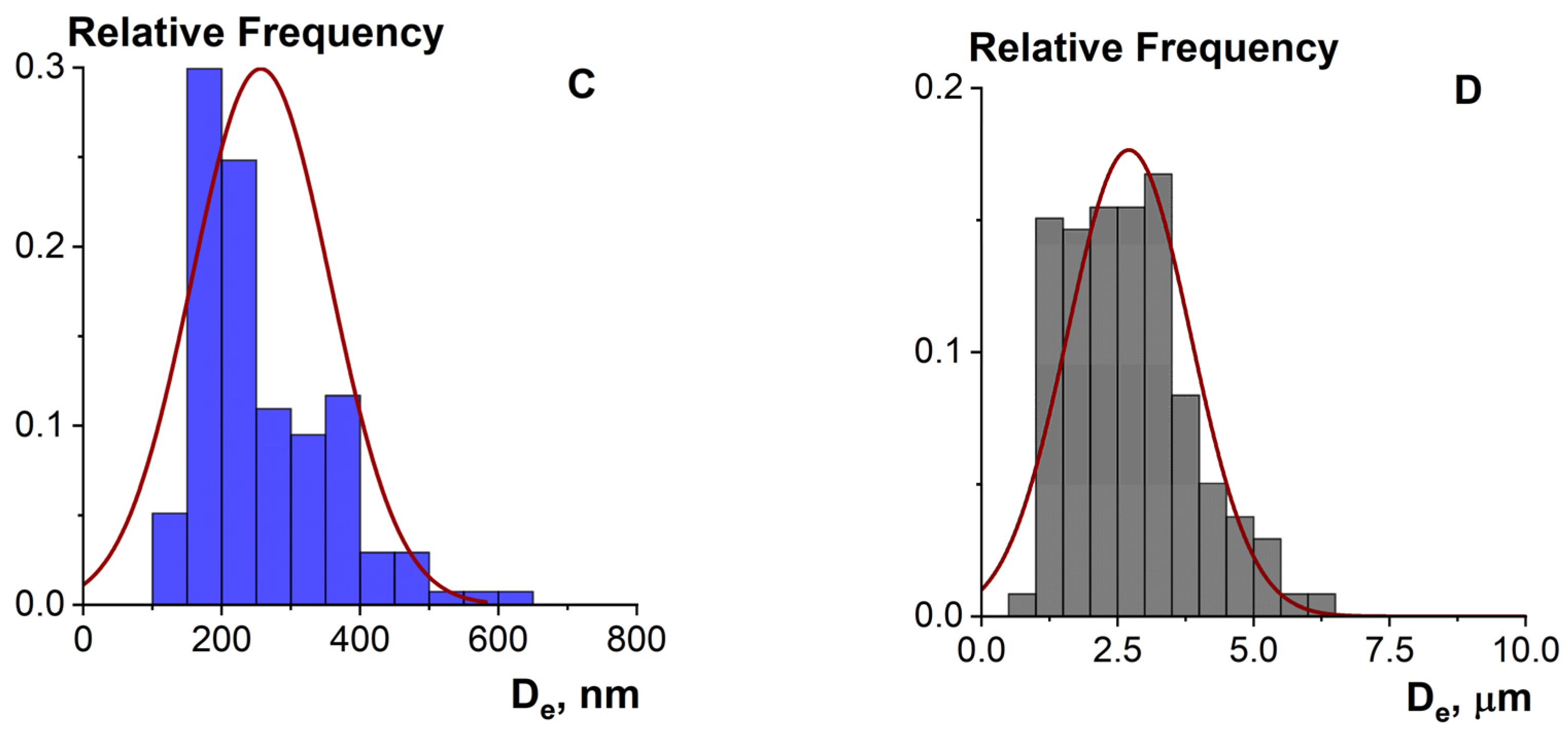

2.4.4. Microstructure Analysis

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

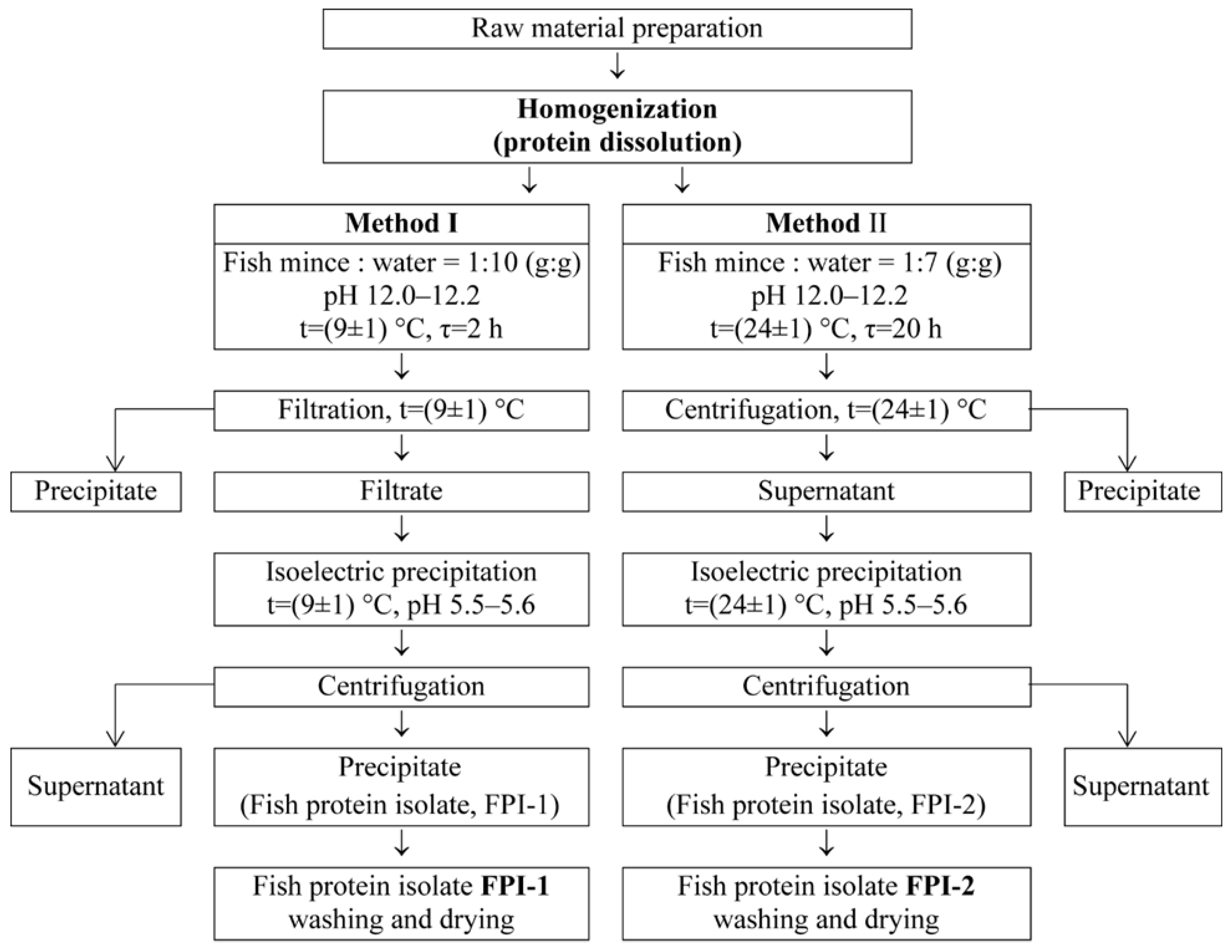

4.2. Preparation of Fish Protein Isolate

4.3. Physicochemical Properties of Fish Protein Isolates

4.3.1. Chemical Composition

4.3.2. Amino Acid Profile by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC)

4.3.3. Molecular Weight Composition by Vertical Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE)

4.3.4. Zeta Potential and Particle Size by Dynamic Light Scattering

4.4. Functional Properties of Fish Protein Isolates

4.4.1. Water Holding Capacity and Fat Binding Capacity

4.4.2. Solubility

4.4.3. Emulsifying Capacity

4.5. Preparation of Heat-Set Fish Protein Isolate Gels

4.6. Physicochemical Properties of Heat-Set Fish Protein Isolate Gels

4.6.1. Thermal Properties by Different Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

4.6.2. Protein Secondary Structure by FT-IR Spectroscopy

4.6.3. Rheological Characteristics

4.6.4. Microstructure by Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

4.7. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FPI | Fish protein isolate |

| FPI-1 | Fish protein isolates with high-molecular mass |

| FPI-2 | Fish protein isolates with low-molecular mass |

| ISP | Isoelectric solubilisation/precipitation |

| FT-IR | Fourier transform infrared |

| DSC | Differential scanning calorimetry |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

References

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations. Available online: https://www.fao.org/home/en/ (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Suresh, P.V.; Brundha, A.R.; Kudre, T.G.; Sandesh, S.K. Valorization of Seafood Processing By-Products for Bioactive Compounds. In Nutraceutics from Agri-Food By-Products, 1st ed.; Spizzirri, U.G., Ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 319–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Ye, X.; Hou, Z.; Chen, S. Sustainable utilization of proteins from fish processing by-products: Extraction, biological activities and applications. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 143, 104276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canti, M.; Martawidjaja, K.L. Physicochemical and sensory properties of kamaboko produced from Asian seabass surimi-catfish protein isolate (Clarias gariepinus). Measur. Food 2024, 15, 100184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés-Sánchez, A.D.J.; Diaz-Ramírez, M.; Torres-Ochoa, E.; Espinosa-Chaurand, L.D.; Rayas-Amor, A.A.; Cruz-Monterrosa, R.G.; Aguilar-Toalá, J.E.; Salgado-Cruz, M.D.L.P. Processing, Quality and Elemental Safety of Fish. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjakul, S.; Yarnpakdee, S.; Senphan, T.; Halldorsdottir, S.M.; Kristinsson, H.G. Fish protein hydrolysates: Production, bioactivities, and applications. In Antioxidants and Functional Components in Aquatic Foods, 1st ed.; Kristinsson, H.G., Ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 237–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubczyk, A.; Karaś, M.; Rybczyńska-Tkaczyk, K.; Zielińska, E.; Zieliński, D. Current Trends of Bioactive Peptides—New Sources and Therapeutic Effect. Foods 2020, 9, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matak, K.E.; Tahergorabi, R.; Jaczynski, J. A review: Protein isolates recovered by isoelectric solubilization/precipitation processing from muscle food by-products as a component of nutraceutical foods. Food Res. Int. 2015, 77, 697–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, G.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Teng, W.; Jin, G.; Geng, F.; Cao, J. Research advances of molecular docking and molecular dynamic simulation in recognizing interaction between muscle proteins and exogenous additives. Food Chem. 2023, 429, 136836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganjeh, A.M.; Saraiva, J.A.; Pinto, C.A.; Casal, S.; Silva, A.M.S. Emergent technologies to improve protein extraction from fish and seafood by-products: An overview. Appl. Food Res. 2023, 3, 100339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Guo, N.; Sun, J.; Xue, C. Comprehensive utilization of shrimp waste based on biotechnological methods: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 814–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surasani, V.K.R. Acid and alkaline solubilization (pH shift) process: A better approach for the utilization of fish processing waste and by-products. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 18345–18363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Cheng, P.; Chu, L.; Zhang, H.; Wang, C.; Shi, R.; Wang, Z.; Han, J.; Fan, Z. Unveiling the rheological and thermal behavior of a novel Salecan and whey protein isolate composite gel. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 271, 132528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasidharan, A.; Venugopal, V. Proteins and Co-products from Seafood Processing Discards: Their Recovery, Functional Properties and Applications. Waste Biomass Valor. 2020, 11, 5647–5663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chang, S.K.C. Color and texture of surimi-like gels made of protein isolate extracted from catfish byproducts are improved by washing and adding soy whey. J. Food Sci. 2022, 87, 3057–3070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Hong, B.; Abdollahi, M.; Wu, H.; Undeland, I. Role of lingonberry press cake in producing stable herring protein isolates via pH-shift processing: A dose response study. Food Chem. X 2024, 22, 101456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somjid, P.; Chaijan, M.; Rawdkuen, S.; Grossmann, L.; Panpipat, W. The Effect of Multistage Refinement on the Bio-Physico-Chemical Properties and Gel-Forming Ability of Fish Protein Isolates from Mackerel (Rastrelliger kanagurta). Foods 2023, 12, 3894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi, M.; Undeland, I. Structural, functional, and sensorial properties of protein isolate produced from salmon, cod, and herring by-products. Food Biopros. Technol. 2018, 11, 1733–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, C.; Lélu, P.; Lynch, S.A.; Tiwari, B.K. Optimised protein recovery from mackerel whole fish by using sequential acid/alkaline isoelectric solubilization precipitation (ISP) extraction assisted by ultrasound. LWT 2018, 88, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-C.; Jaczynski, J. Protein Recovery from Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) Processing Byproducts via Isoelectric Solubilization/Precipitation and Its Gelation Properties As Affected by Functional Additives. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 9079–9088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.; Liu, S.; Cao, J.; Chen, S.; Wang, W.; Qin, X. Fish Protein Isolates Recovered from Silver Carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix) By-Products Using Alkaline pH Solubilization and Precipitation. J. Aquat. Food Prod. Technol. 2016, 25, 400–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.; Wang, C.; Yang, H.; Xiong, S.; Liu, Y.; Liu, R. Effects of the Acid- and Alkali-Aided Processes on Bighead Carp (Aristichthys nobilis) Muscle Proteins. Int. J. Food Prop. 2016, 19, 1863–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Sun, D.-W. Naturally sourced biosubstances for regulating freezing points in food researches: Fundamentals, current applications and future trends. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 95, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khiari, Z.; Kelloway, S.; Mason, B. Turning Invasive Green Crab (Carcinus maenas) into Opportunity: Recovery of Chitin and Protein Isolate Through Isoelectric Solubilization/Precipitation. Waste Biomass Valor. 2020, 11, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Yang, H. Effects of calcium ion on gel properties and gelation of tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) protein isolates processed with pH shift method. Food Chem. 2019, 277, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdollahi, M.; Undeland, I. Physicochemical and gel-forming properties of protein isolated from salmon, cod and herring by-products using the pH-shift method. LWT 2019, 101, 678–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smaoui, S.; Hosseini, E.; Tsegay, Z.T.; D’Amore, T.; Varzakas, T. Sustainable valorisation of seafood-derived proteins: Current approaches for recovery and applications in biomedical and food systems. Food Biosci. 2024, 62, 105450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Ahmmed, M.K.; Regenstein, J.M.; Wu, H. Recent advances of recycling proteins from seafood by-products: Industrial applications, challenges, and breakthroughs. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 149, 104533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Dai, Z.; Chen, Z.; Hao, Y.; Wang, S.; Mao, X. Improved gelling and emulsifying properties of myofibrillar protein from frozen shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) by high-intensity ultrasound. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 135, 108188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefi, N.; Abbasi, S. Food proteins: Solubility & thermal stability improvement techniques. Food Chem. Adv. 2022, 1, 100090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossmann, L.; McClements, D.J. Current insights into protein solubility: A review of its importance for alternative proteins. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 137, 108416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, K.; Rao, J.; Chen, B. Plant protein solubility: A challenge or insurmountable obstacle. Adv. Colloid Interf. Sci. 2024, 324, 103074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.K.; Greis, M.; Lu, J.; Nolden, A.A.; McClements, D.J.; Kinchla, A.J. Functional Performance of Plant Proteins. Foods 2022, 11, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yáñez-Ruiz, D.R.; Martín-García, A.I.; Weisbjerg, M.R.; Hvelplund, T.; Molina-Alcaide, E. A comparison of different legume seeds as protein supplement to optimise the use of low quality forages by ruminants. Arch. Anim. Nutrit. 2009, 63, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Zou, B.; Du, J.; Na, X.; Du, M.; Zhu, B.; Wu, C. Soluble nano-sized aggregates of Alaska pollock proteins engineered by the refolding process of pH-shifting. Food Res. Int. 2025, 203, 115829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossmann, L.; Weiss, J. Alternative Protein Sources as Technofunctional Food Ingredients. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 12, 93–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Vila, S.; Fenelon, M.; Hennessy, D.; O’Mahony, J.A.; Gómez-Mascaraque, L.G. Impact of the extraction method on the composition and solubility of leaf protein concentrates from perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.). Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 147, 109372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canti, M.; Sulistio, M.F.; Wirawan, C.A.; Prasetyanto, Y.E.A.; Lestari, D. A comparison of physicochemical, functional, and sensory properties of catfishprotein isolate (Clarias gariepinus) produced using different defatting solvent. Food Res. 2023, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Xiong, H.; Shi, S.; Hu, J.; Peng, H.; Zhou, Q.; Sun, W. Physicochemical and functional properties of the protein isolate and major fractions prepared from Akebia trifoliata var. Australis seed. Food Chem. 2012, 133, 923–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotnala, B.; Panneerselvam, V.; Vijayakumar, A.K. Physicochemical, structural, and functional characterization of guar meal protein isolate (Cyamopsis tetragonoloba). Heliyon 2024, 10, e24925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azadian, M.; Moosavi-Nasab, M.; Abedi, E. Comparison of functional properties and SDS-PAGE patterns between fish protein isolate and surimi produced from silver carp. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2012, 235, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, R.; Chang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Li, Z.; Xue, C. Preparation and thermo-reversible gelling properties of protein isolate from defatted Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba) byproducts. Food Chem. 2015, 188, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Singh, N.; Kaur, A.; Virdi, A.S.; Dar, O.I.; Sharma, S. Functional properties and dynamic rheology of protein isolates extracted from male and female common carp (Cyprinus carpio) muscle subjected to pH-shifting method. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2019, 43, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Gao, P.; Jiang, Q.; Chen, H.; Yang, F.; Yu, P.; Yu, D.; Xia, W. Modification of myofibrillar protein using combined chicken breast and soybean protein isolate for improving gel properties: Protein structure and intermolecular interactions. Food Hydrocol. 2025, 164, 111215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canti, M.; Owen, J.; Putra, M.F.; Hutagalung, R.A.; Utami, N. Development of patty meat analogue using anchovy protein isolate (Stolephorus insularis) as a binding agent. Heliyon 2024, 10, e23463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joint WHO/FAO/UNU Expert Consultation. Protein and Amino Acid Requirements in Human Nutrition; WHO Technical Report Series; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007; Volume 935, pp. 1–265.

- Arise, A.K.; Alashi, A.M.; Nwachukwu, I.D.; Ijabadeniyi, O.A.; Aluko, R.E.; Amonsou, E.O. Antioxidant activities of bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea) protein hydrolysates and their membrane ultrafiltration fractions. Food Funct. 2016, 7, 2431–2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, I.-J.; Larsen, R.; Rustad, T.; Eilertsen, K.-E. Nutritional content and bioactive properties of wild and farmed cod (Gadus morhua L.) subjected to food preparation. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2013, 31, 212–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, H.; Xia, X.; Wang, C.; Kong, B.; Liu, Q. Thermal stability and gel quality of myofibrillar protein as affected by soy protein isolates subjected to an acidic pH and mild heating. Food Chem. 2018, 242, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.-K.; Lee, M.H.; Yong, H.I.; Kang, M.-C.; Jung, S.; Choi, Y.-S. Porcine myofibrillar protein gel with edible insect protein: Effect of pH-shifting. LWT 2022, 154, 112629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverstein, R.M.; Webster, F.X.; Kiemle, D.J. Spectrometric Identification of Organic Compounds, 7th ed.; J. Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Litvinov, R.I.; Faizullin, D.A.; Zuev, Y.F.; Weisel, J.W. The α-Helix to β-Sheet Transition in Stretched and Compressed Hydrated Fibrin Clots. Biophys. J. 2012, 103, 1020–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, J.; Yu, S. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopic Analysis of Protein Secondary Structures. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2007, 39, 549–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, Y.; Mayer, S.G.; Park, J.W. FT-IR and Raman spectroscopies determine structural changes of tilapia fish protein isolate and surimi under different comminution conditions. Food Chem. 2017, 226, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, K.; Wilhelm, M.; Klein, C.O.; Cho, K.S.; Nam, J.G.; Ahn, K.H.; Lee, S.J.; Ewoldt, R.H.; McKinley, G.H. A review of nonlinear oscillatory shear tests: Analysis and application of large amplitude oscillatory shear (LAOS). Prog. Polym. Sci. 2011, 36, 1697–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malkin, A.Y.; Derkach, S.R.; Kulichikhin, V.G. Rheology of Gels and Yielding Liquids. Gels 2023, 9, 715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, U.; Lin, Y.; Zuo, X.; Zheng, H. Soft matter approach for creating novel protein hydrogels using fractal whey protein assemblies as building blocks. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 151, 109828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, Y.; Mayer, S.G.; Park, J.W. Gelation properties of tilapia fish protein isolate and surimi pre- and post-rigor. Food Biosci. 2017, 17, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malkin, A.Y.; Derkach, S.R. Gelation of polymer solutions as a rheological phenomenon (mechanisms and kinetics). Curr. Opin. Colloid Interf. Sci. 2024, 73, 101844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malkin, A.Y.; Isayev, A.I. Rheology: Concepts, Methods, and Applications, 3rd ed.; ChemTec Publishing: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Derkach, S.R.; Voron’ko, N.G.; Kuchina, Y.A.; Kolotova, D.S.; Grokhovsky, V.A.; Nikiforova, A.A.; Sedov, I.A.; Faizullin, D.A.; Zuev, Y.F. Rheological Properties of Fish and Mammalian Gelatin Hydrogels as Bases for Potential Practical Formulations. Gels 2024, 10, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derkach, S.R.; Kuchina, Y.A.; Kolotova, D.S.; Petrova, L.A.; Volchenko, V.I.; Glukharev, A.Y.; Grokhovsky, V.A. Properties of Protein Isolates from Marine Hydrobionts Obtained by Isoelectric Solubilisation/Precipitation: Influence of Temperature and Processing Time. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latimer, G.W.; AOAC International (Eds.) Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International, 20th ed.; AOAC International: Rockville, MD, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Vinayashree, S.; Vasu, P. Biochemical, nutritional and functional properties of protein isolate and fractions from pumpkin (Cucurbita moschata var. Kashi Harit) seeds. Food Chem. 2021, 340, 128177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benelhadj, S.; Gharsallaoui, A.; Degraeve, P.; Attia, H.; Ghorbel, D. Effect of pH on the functional properties of Arthrospira (Spirulina) platensis protein isolate. Food Chem. 2016, 194, 1056–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acateca-Hernández, M.I.; Hernández-Cázares, A.S.; Hidalgo-Contreras, J.V.; Jiménez-Munguía, M.T.; Ríos-Corripio, M.A. Evaluation of the functional properties of a protein isolate from Arthrospira maxima and its application in a meat sausage. Heliyon 2024, 10, e33500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odelli, D.; Rodrigues, S.R.; Silva De Sousa, L.; Nogueira Silva, N.F.; López Martínez, A.L.; Queiroz, L.S.; Casanova, F.; Carvalho, A.F.D. Effect of konjac glucomannan on heat-induced pea protein isolate hydrogels: Evaluation of structure and formation mechanisms. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 156, 110310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojdyr, M. Fityk: A general-purpose peak fitting program. J. Appl. Crystall. 2010, 43, 1126–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, A.; Huang, P.; Caughey, W.S. Protein secondary structures in water from second-derivative amide I infrared spectra. Biochemistry 1990, 29, 3303–3308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezeshk, S.; Rezaei, M.; Hosseini, H.; Abdollahi, M. Impact of pH-shift processing combined with ultrasonication on structural and functional properties of proteins isolated from rainbow trout by-products. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 118, 106768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Moisture ωM (%) | Total Nitrogen NT (%) | Protein * P (%) | Mineral Substances ωA (%) | Yield B (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FPI-1 | 5.2 ± 0.1 a | 15.0 ± 0.1 a | 93.8 ± 0.6 a | 0.7 ± 0.01 a | 10.4 ± 0.6 a |

| FPI-2 | 5.9 ± 0.1 b | 15.0 ± 0.1 a | 93.8 ± 0.6 a | 0.4 ± 0.1 b | 14.4 ± 0.7 b |

| Protein-containing raw material | 80 ± 1 c | 3.0 ± 0.1 b | 18.8 ± 0.6 b | 0.9 ± 0.1 c | – |

| Isolates | WHC, g/g | FHC, g/g | EC, % | EAI, m2/g | ESI, min | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water, pH 5.6–6.2 | Buffer, pH 7.0 | |||||

| FPI-1 | 6.2 ± 0.1 a | 8.6 ± 0.1 a | 3.0 ± 0.1 a | 66 a | 29.3 a | 100.8 a |

| FPI-2 | 5.8 ± 0.1 b | 8.3 ± 0.1 b | 2.8 ± 0.1 a | 93 b | 31.6 b | 546.0 b |

| Samples | Heating Rate (°C/min) | Tg (°C) | Tb (°C) | Td (°C) | ΔHg (J/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FPI-1 | 10 | 150.0 ± 0.8 a | 158.2 ± 1.0 a | ||

| 20 | 64.5 ± 0.5 a | 120.2 ± 0.1 b | 163.0 ± 1.9 b | 67.4 ± 1.2 a | |

| FPI-2 | 10 | 134.5 ± 0.8 c | 140.9 ± 2.0 c | ||

| 20 | 70.3 ± 0.9 b | 115.8 ± 0.2 d | 158.5 ± 0.6 d | 66.9 ± 1.0 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Derkach, S.; Kuchina, Y.; Kolotova, D.; Borovinskaya, E.; Voropaeva, S.; Voron’ko, N.; Nikiforova, A.; Klimovitskaya, M.; Klimovitskii, A.; Abramov, V.; et al. Food Gels of Fish Protein Isolate from Atlantic Cod (Gadus morhua) By-Products Recovered by pH Shift. Gels 2025, 11, 970. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120970

Derkach S, Kuchina Y, Kolotova D, Borovinskaya E, Voropaeva S, Voron’ko N, Nikiforova A, Klimovitskaya M, Klimovitskii A, Abramov V, et al. Food Gels of Fish Protein Isolate from Atlantic Cod (Gadus morhua) By-Products Recovered by pH Shift. Gels. 2025; 11(12):970. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120970

Chicago/Turabian StyleDerkach, Svetlana, Yuliya Kuchina, Daria Kolotova, Ekaterina Borovinskaya, Svetlana Voropaeva, Nikolay Voron’ko, Alena Nikiforova, Mariya Klimovitskaya, Alexander Klimovitskii, Vladislav Abramov, and et al. 2025. "Food Gels of Fish Protein Isolate from Atlantic Cod (Gadus morhua) By-Products Recovered by pH Shift" Gels 11, no. 12: 970. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120970

APA StyleDerkach, S., Kuchina, Y., Kolotova, D., Borovinskaya, E., Voropaeva, S., Voron’ko, N., Nikiforova, A., Klimovitskaya, M., Klimovitskii, A., Abramov, V., Anikeenko, E., & Zuev, Y. (2025). Food Gels of Fish Protein Isolate from Atlantic Cod (Gadus morhua) By-Products Recovered by pH Shift. Gels, 11(12), 970. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120970