Impact of CeO2-Doped Bioactive Glass on the Properties of CMC/PEG Hydrogels Intended for Wound Treatment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

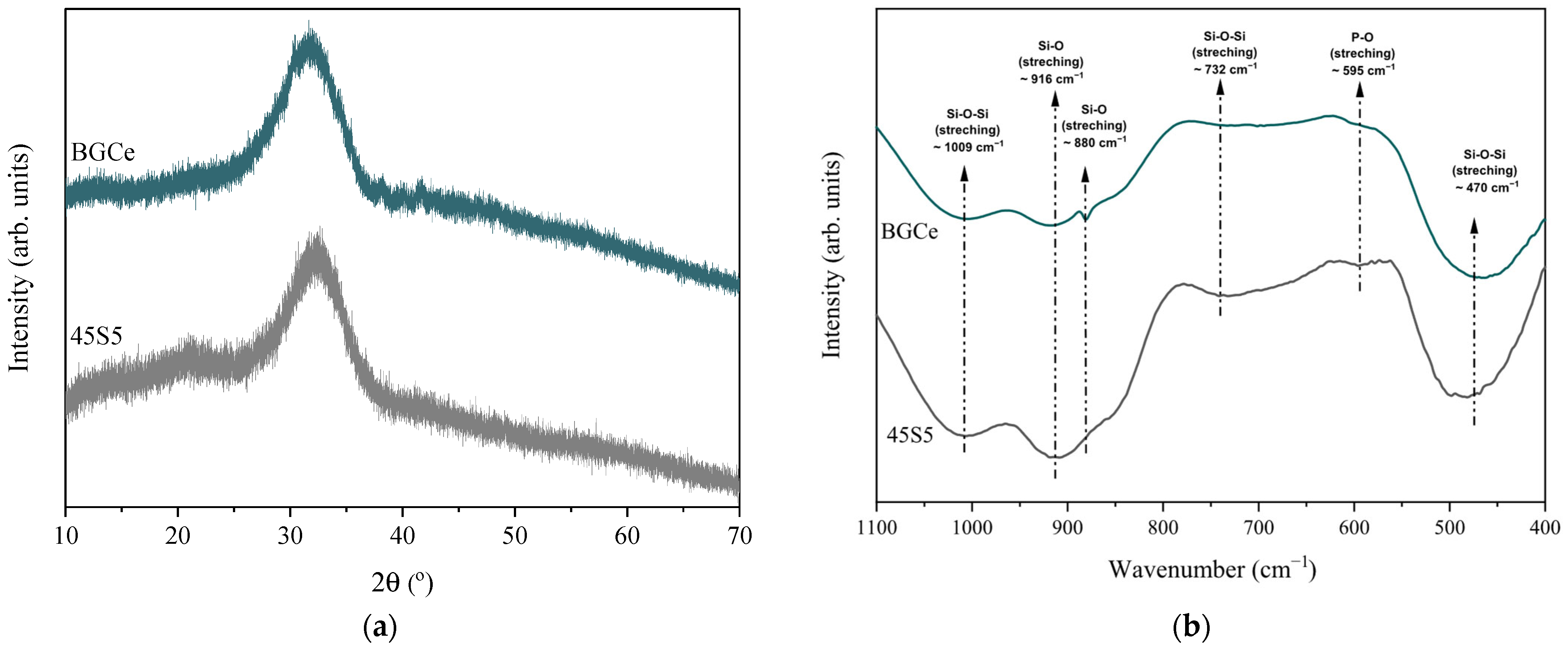

2.1. Bioglass Characterisation

2.1.1. Bioglass Structural Analysis

2.1.2. Bioglass Morphological Analysis

2.2. Hydrogel Characterisation

2.2.1. Hydrogel Structural Analysis

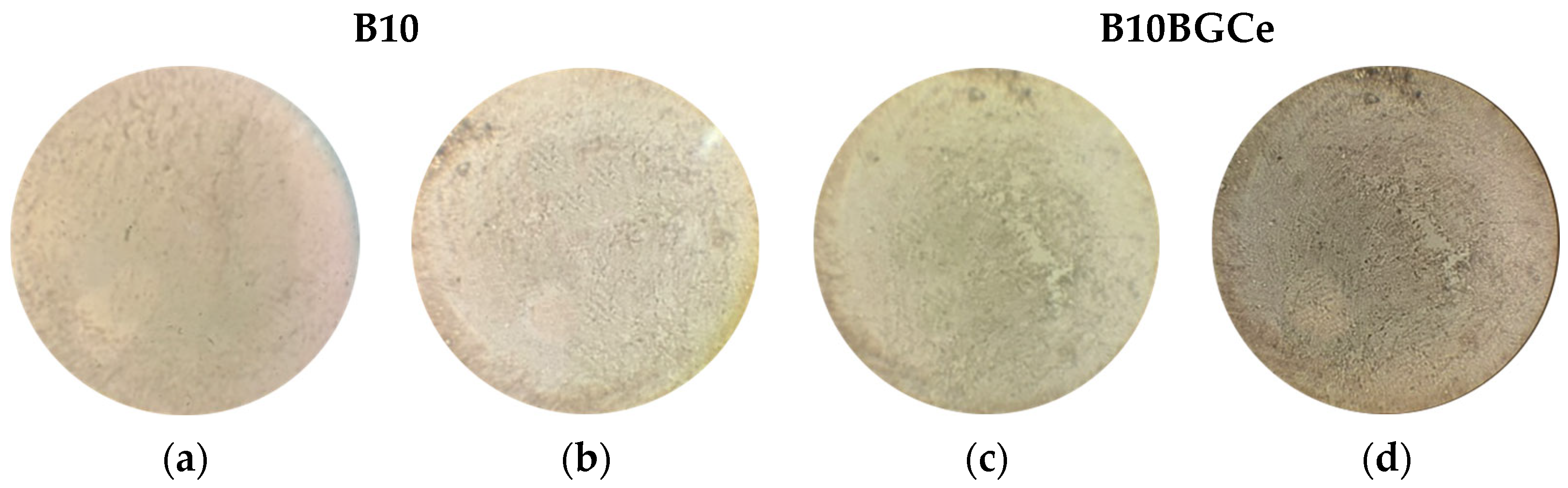

2.2.2. Hydrogel Morphological Analysis

2.3. Physical, Biological and Mechanical Properties

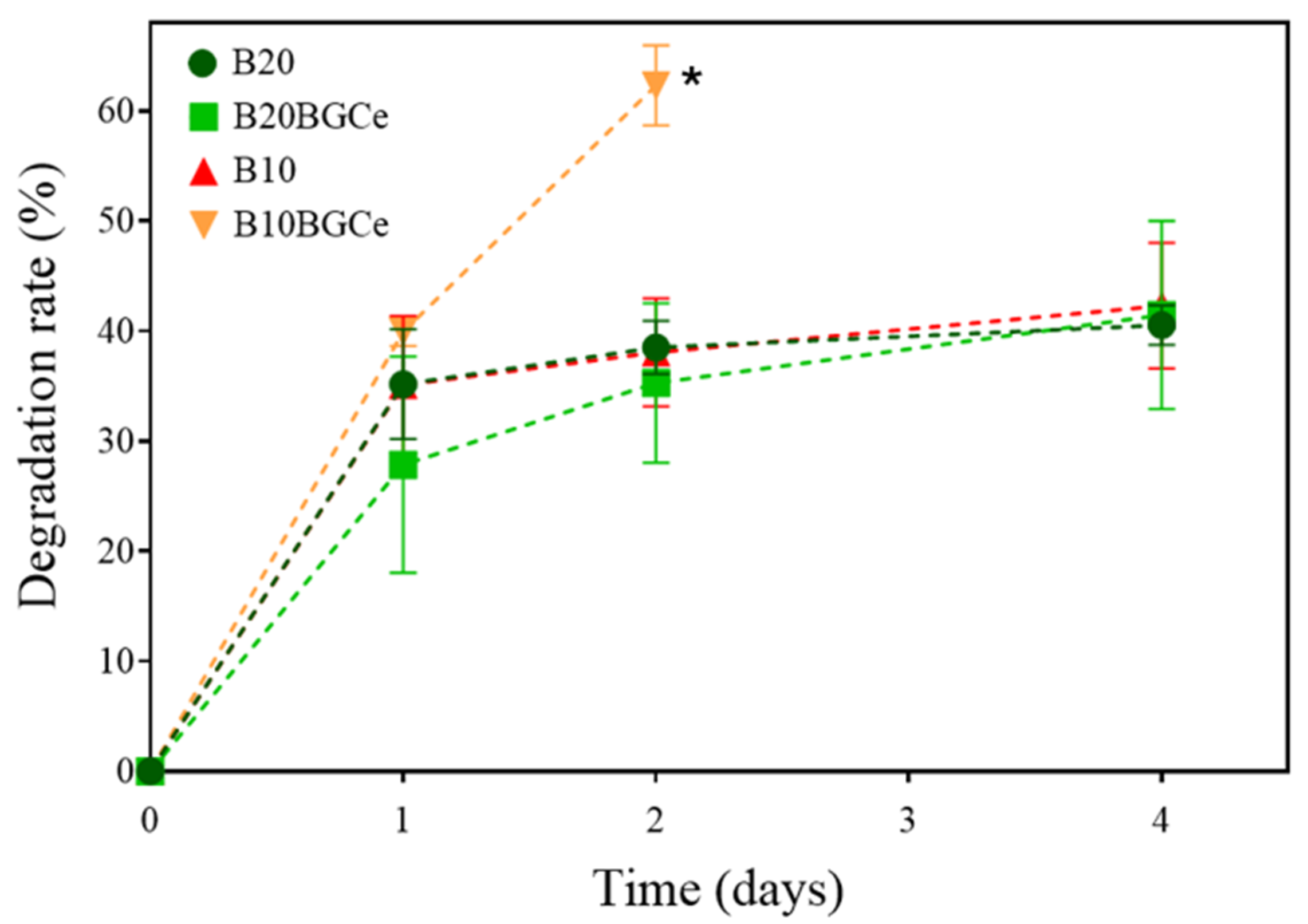

2.3.1. Swelling Ratio and Degradation Rate

2.3.2. Biocompatibility

2.3.3. Bending Strength

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Synthesis of Bioglass 45S5 Doped with CeO2

4.3. Synthesis of Bioglass-Containing Hydrogels

4.4. Materials Characterisation

4.4.1. Characterisation of the Bioglass

4.4.2. Characterisation of the Hydrogels

Structural and Morphological Characterisation

Swelling and Degradation Studies

Biocompatibility

Mechanical Tests

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ATR | Attenuated total reflection |

| BG | Bioactive glasses |

| C | Carbon |

| CA | Citric acid |

| Ca | Calcium |

| CaCO3 | Calcium carbonate |

| CaO | Calcium oxide |

| Ce | Cerium |

| CeO2 | Cerium oxide |

| CMC | Carboxymethyl cellulose |

| CO2 | Carbon dioxide |

| Da | Dalton |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| EDS | Energy dispersive spectroscopy |

| FTIR | Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy |

| h | Hours |

| H2O | Water |

| IDF | International Diabetes Federation |

| min | Minutes |

| Na | Sodium |

| Na2O | Sodium oxide |

| P | Phosphorus |

| P2O5 | Phosphorous pentoxide |

| PEG | Polyethylene glycol |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| rpm | Rotation per minute |

| RT | Room temperature |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| Si | Silicon |

| SiO2 | Silica |

| SiO4 | Silicate tetrahedron |

| SRB | Sulforhodamine B |

| TCA | Trichloroacetic acid |

| USD | United States dollar |

| UV | Ultraviolet radiation |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

References

- Cheng, L.; Zhuang, Z.; Yin, M.; Lu, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhan, M.; Zhao, L.; He, Z.; Meng, F.; Tian, S.; et al. A Microenvironment-Modulating Dressing with Proliferative Degradants for the Healing of Diabetic Wounds. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 9786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Diabetes Data_World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diabetes (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas_11h Edition 2025; Federated Identity Management, International Diabetes Federation: Brussels, Belgium, 2024; Available online: https://diabetesatlas.org/ (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Pinto, A.M.; Cerqueira, M.A.; Bañobre-Lópes, M.; Pastrana, L.M.; Sillankorva, S. Bacteriophages for Chronic Wound Treatment: From Traditional to Novel Delivery Systems. Viruses 2020, 12, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gounden, V.; Singh, M. Hydrogels and Wound Healing: Current and Future Prospects. Gels 2024, 10, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Dou, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Li, F.; Xing, B.; Hu, Z.; Li, X.; Liu, Z.; Yang, W.; Liu, Z. Smart Responsive and Controlled-Release Hydrogels for Chronic Wound Treatment. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, H.; Tian, P.; Hao, L.; Hu, C.; Liu, B.; Meng, F.; Yi, X.; Pan, X.; Hu, X.; Wang, H.; et al. Antioxidative Bioactive Glass Reinforced Injectable Hydrogel with Reactive Oxygen Species Scavenging Capacity for Diabetic Wounds Treatment. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 481, 148768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Zhou, Y.; Peng, J.; Xu, C.; Xu, Q.; Xing, M.; Chang, J. A Novel Dual-Adhesive and Bioactive Hydrogel Activated by Bioglass for Wound Healing. NPG Asia Mater. 2019, 11, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabi, T.; Mesgar, A.S.; Mohammadi, Z. Bioactive Glasses: A Promising Therapeutic Ion Release Strategy for Enhancing Wound Healing. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 6, 5399–5430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, L.; Yu, L.; Chen, S.; Huang, D.; Yang, C.; Deng, H.; Hu, Y.; Wang, H.; Wen, Z.; Wang, Y.; et al. The Regulatory Mechanisms of Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles in Oxidative Stress and Emerging Applications in Refractory Wound Care. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1439960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wu, Q.; Fan, X.; Yang, L.; Zou, L.; Liu, Q.; Shi, G.; Yang, X.; Tang, K. Study on Chitosan/Gelatin Hydrogels Containing Ceria Nanoparticles for Promoting the Healing of Diabetic Wound. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2024, 112, 1532–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, S.; Ling, J.; Wang, N.; Ouyang, X.K. Cerium Dioxide Nanozyme Doped Hybrid Hydrogel with Antioxidant and Antibacterial Abilities for Promoting Diabetic Wound Healing. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 497, 154517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Chen, Q.; Yin, R.; Yuan, X.; Kang, H.; Cai, A.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, H. Photothermal Effect and Antimicrobial Properties of Cerium-Doped Bioactive Glasses. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 20235–20246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavinho, S.R.; Pádua, A.S.; Sá-Nogueira, I.; Silva, J.C.; Borges, J.P.; Costa, L.C.; Graça, M.P.F. Biocompatibility, Bioactivity, and Antibacterial Behaviour of Cerium-Containing Bioglass®. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 4479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavinho, S.R.; Graça, M.P.F.; Prezas, P.R.; Kumar, J.S.; Melo, B.M.G.; Sales, A.J.M.; Almeida, A.F.; Valente, M.A. Structural, Thermal, Morphological and Dielectric Investigations on 45S5 Glass and Glass-Ceramics. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2021, 562, 120780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Damrawi, G.; Behairy, A. Structural Role of Cerium Oxide in Lead Silicate Glasses and Glass Ceramics. J. Miner. Mater. Charact. Eng. 2018, 6, 438–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavinho, S. Customization of Implants Coated with Multifunctional Biomaterials. Doctoral Thesis, University of Aveiro, Aveiro, Portugal, 2024. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10773/42313 (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Regadas, J.S.; Gavinho, S.R.; Teixeira, S.S.; de Jesus, J.V.; Pádua, A.S.; Silva, J.C.; Devesa, S.; Graça, M.P.F. Influence of the Particle Size on the Electrical, Magnetic and Biological Properties of the Bioglass® Containing Iron Oxide. Magnetochemistry 2023, 9, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeimaran, E.; Pourshahrestani, S.; Fathi, A.; bin Abd Razak, N.A.; Kadri, N.A.; Sheikhi, A.; Baino, F. Advances in Bioactive Glass-Containing Injectable Hydrogel Biomaterials for Tissue Regeneration. Acta Biomater. 2021, 136, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regadas, J. Antioxidant and Pro-Oxidant Properties of Bioglass Dopped with Cerium and Iron. Master’s Thesis, University of Aveiro, Aveiro, Portugal, 2024. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10773/44620 (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Araújo, M.; Miola, M.; Baldi, G.; Perez, J.; Verné, E. Bioactive Glasses with Low Ca/P Ratio and Enhanced Bioactivity. Materials 2016, 9, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorpade, V.S.; Yadav, A.V.; Dias, R.J.; Mali, K.K.; Pargaonkar, S.S.; Shinde, P.V.; Dhane, N.S. Citric Acid Crosslinked Carboxymethylcellulose-Poly(Ethylene Glycol) Hydrogel Films for Delivery of Poorly Soluble Drugs. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 118, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capanema, N.S.V.; Mansur, A.A.P.; de Jesus, A.C.; Carvalho, S.M.; de Oliveira, L.C.; Mansur, H.S. Superabsorbent Crosslinked Carboxymethyl Cellulose-PEG Hydrogels for Potential Wound Dressing Applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 106, 1218–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mojahedi, M.; Zargar Kharazi, A.; Poorazizi, E. Preparation and Characterization of Carboxymethyl Cellulose/Polyethylene Glycol Films Containing Bromelain/Curcumin: In Vitro Evaluation of Wound Healing Activity. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2024, 64, 1993–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suo, A.; Qian, J.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, W. Synthesis and Properties of Carboxymethyl Cellulose-Graft-Poly(Acrylic Acid-Co-Acrylamide) as a Novel Cellulose-Based Šuperabsorbent. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2007, 103, 1382–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temel-Soylu, T.M.; Keçeciler-Emir, C.; Rababah, T.; Özel, C.; Yücel, S.; Basaran-Elalmis, Y.; Altan, D.; Kirgiz, Ö.; Seçinti, İ.E.; Kaya, U.; et al. Green Electrospun Poly(Vinyl Alcohol)/Gelatin-Based Nanofibrous Membrane by Incorporating 45S5 Bioglass Nanoparticles and Urea for Wound Dressing Applications: Characterization and In Vitro and In Vivo Evaluations. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 21187–21203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sherbiny, I.M.; Yacoub, M.H. Hydrogel Scaffolds for Tissue Engineering: Progress and Challenges. Glob. Cardiol. Sci. Pract. 2013, 2013, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, M.Z.; Bernero, M.; Xie, C.; Qiu, W.; Oggianu, E.; Rabut, L.; Michaels, T.C.T.; Style, R.W.; Müller, R.; Qin, X.H. Cell-Guiding Microporous Hydrogels by Photopolymerization-Induced Phase Separation. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 4923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farid, E.; Kamoun, E.A.; Taha, T.H.; El-Dissouky, A.; Khalil, T.E. PVA/CMC/Attapulgite Clay Composite Hydrogel Membranes for Biomedical Applications: Factors Affecting Hydrogel Membranes Crosslinking and Bio-Evaluation Tests. J. Polym. Environ. 2022, 30, 4675–4689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Aguinagalde, O.; Lejardi, A.; Meaurio, E.; Hernández, R.; Mijangos, C.; Sarasua, J.R. Novel Hydrogels of Chitosan and Poly (Vinyl Alcohol) Reinforced with Inorganic Particles of Bioactive Glass. Polymers 2021, 13, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Q.; Han, Y.; Li, H.; Chang, J. Design of a Thermosensitive Bioglass/Agarose-Alginate Composite Hydrogel for Chronic Wound Healing. J. Mater. Chem. B 2015, 3, 8856–8864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, D.; Sun, X.; Liang, L.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.N. Gelatin-Based Hydrogels Blended with Gellan as an Injectable Wound Dressing. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 4766–4775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinthong, T.; Yooyod, M.; Daengmankhong, J.; Tuancharoensri, N.; Mahasaranon, S.; Viyoch, J.; Jongjitwimol, J.; Ross, S.; Ross, G.M. Development of Natural Active Agent-Containing Porous Hydrogel Sheets with High Water Content for Wound Dressings. Gels 2023, 9, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Liu, P.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, L.; Zhao, Z.; Ding, Z.; Wang, T.; Dong, T.; Chen, H.; Liu, J. Hydrogel for Slow-Release Drug Delivery in Wound Treatment. J. Polym. Eng. 2024, 44, 637–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Zhao, F.; Zhang, W.; Mo, Y.; Zeng, L.; Li, X.; Chen, X. Sequentially-Crosslinked Biomimetic Bioactive Glass/Gelatin Methacryloyl Composites Hydrogels for Bone Regeneration. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2018, 89, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peppas, N.A.; Bures, P.; Leobandung, W.; Ichikawa, H. Hydrogels in Pharmaceutical Formulations. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2000, 50, 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawadkar, P.; Lali, F.; Garcia-Gareta, E.; Garrido, B.G.; Chaudhry, A.; Matharu, P.; Kyriakidis, C.; Greco, K. Innovative Hydrogels in Cutaneous Wound Healing: Current Status and Future Perspectives. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2025, 13, 1454903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malavasi, G.; Salvatori, R.; Zambon, A.; Lusvardi, G.; Rigamonti, L.; Chiarini, L.; Anesi, A. Cytocompatibility of Potential Bioactive Cerium-Doped Glasses Based on 45S5. Materials 2019, 12, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silina, E.V.; Manturova, N.E.; Sevastianov, V.I.; Perova, N.V.; Gladchenko, M.P.; Kryukov, A.A.; Ivanov, A.V.; Dudka, V.T.; Prazdnova, E.V.; Emelyantsev, S.A.; et al. Development of a Collagen–Cerium Oxide Nanohydrogel for Wound Healing: In Vitro and In Vivo Evaluation. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Ding, X.; Hua, D.; Liu, M.; Yang, M.; Gong, Y.; Ye, N.; Chen, X.; He, J.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Enhancing Dengue Virus Production and Immunogenicity with CelcradleTM Bioreactor: A Comparative Study with Traditional Cell Culture Methods. Vaccines 2024, 12, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, R.D.; Prasad, R.S.; Prasad, R.B.; Prasad, S.R.; Singha, S.B.; Singha, A.D.; Prasad, R.J.; Teli, S.B.; Sinha, P.; Vaidya, A.K.; et al. A Review on Modern Characterization Techniques for Analysis of Nanomaterials and Biomaterials. ES Energy Environ. 2024, 23, 1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, B.; Pereira, E.; Ferreira-Filho, V.C.; Pires, A.S.; Pereira, L.C.J.; Soares, P.I.P.; Botelho, M.F.; Mendes, F.; Graça, M.P.F.; Teixeira, S.S. Influence of the PH Synthesis of Fe3O4 Magnetic Nanoparticles on Their Applicability for Magnetic Hyperthermia: An In Vitro Analysis. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Samples | SiO2 | P2O5 | CaO | Na2O | CeO2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bioglass 45S5 (control) | 46.1 | 2.6 | 26.9 | 24.4 | - |

| BGCe | 43.8 | 2.5 | 25.6 | 23.1 | 5 |

| Samples | CMC (g) | PEG (g) | CA (% w/w) |

|---|---|---|---|

| B0 | 3.6 | 0.4 | 0 |

| B10 | 10 | ||

| B20 | 20 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pacheco, S.; Marques, I.A.; Pires, A.S.; Botelho, M.F.; Teixeira, S.S.; Graça, M.; Gavinho, S. Impact of CeO2-Doped Bioactive Glass on the Properties of CMC/PEG Hydrogels Intended for Wound Treatment. Gels 2025, 11, 1010. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11121010

Pacheco S, Marques IA, Pires AS, Botelho MF, Teixeira SS, Graça M, Gavinho S. Impact of CeO2-Doped Bioactive Glass on the Properties of CMC/PEG Hydrogels Intended for Wound Treatment. Gels. 2025; 11(12):1010. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11121010

Chicago/Turabian StylePacheco, Sofia, Inês Alexandra Marques, Ana Salomé Pires, Maria Filomena Botelho, Sílvia Soreto Teixeira, Manuel Graça, and Sílvia Gavinho. 2025. "Impact of CeO2-Doped Bioactive Glass on the Properties of CMC/PEG Hydrogels Intended for Wound Treatment" Gels 11, no. 12: 1010. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11121010

APA StylePacheco, S., Marques, I. A., Pires, A. S., Botelho, M. F., Teixeira, S. S., Graça, M., & Gavinho, S. (2025). Impact of CeO2-Doped Bioactive Glass on the Properties of CMC/PEG Hydrogels Intended for Wound Treatment. Gels, 11(12), 1010. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11121010