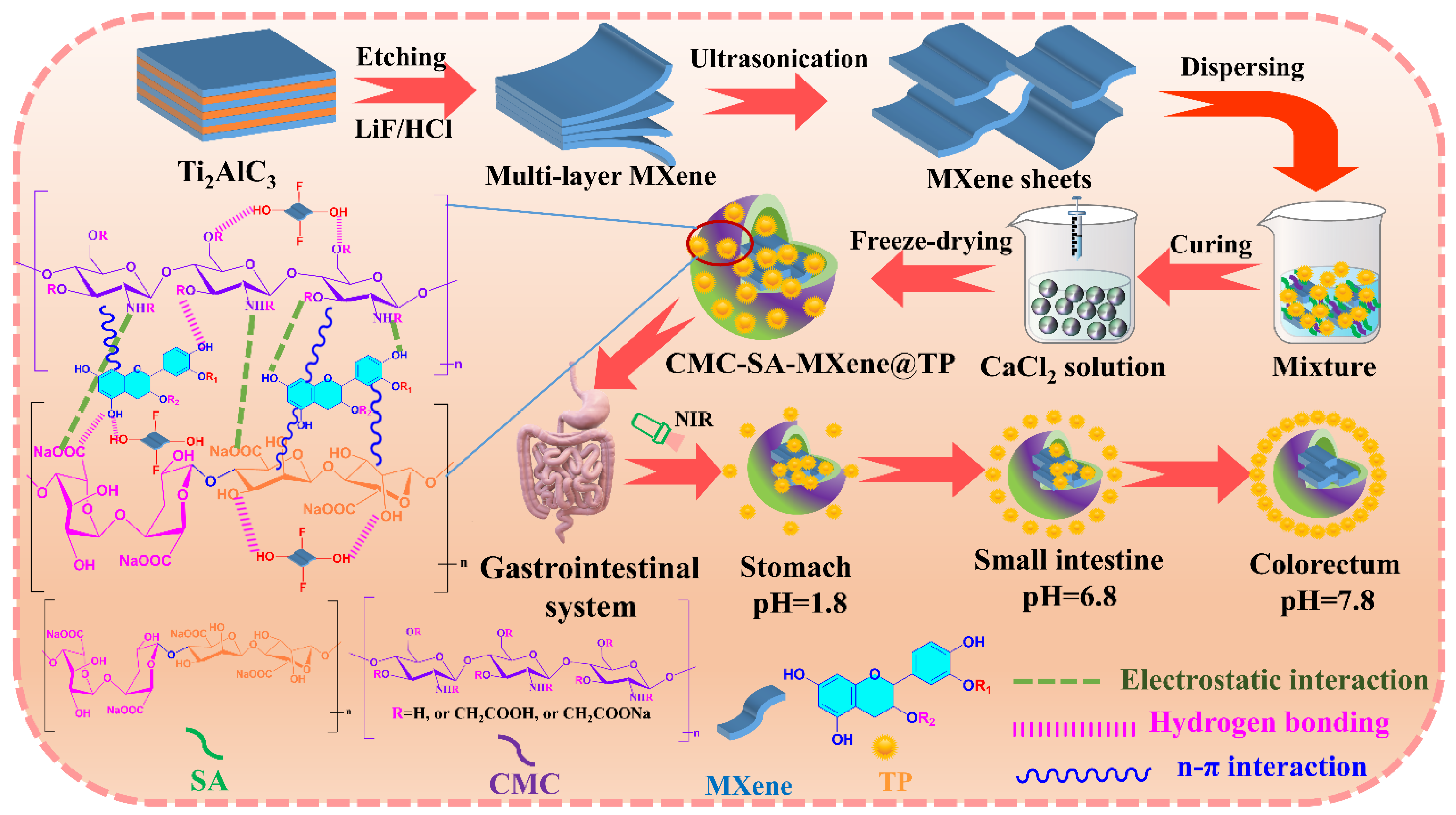

Smart pH/Near-Infrared Light-Responsive Carboxymethyl Chitosan/Sodium Alginate/MXene Hydrogel Beads for Targeted Tea Polyphenols Delivery

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Characterization Analysis

2.2. TPC and Release Studies

2.3. TP Release Studies

2.4. Antioxidant Activity Test

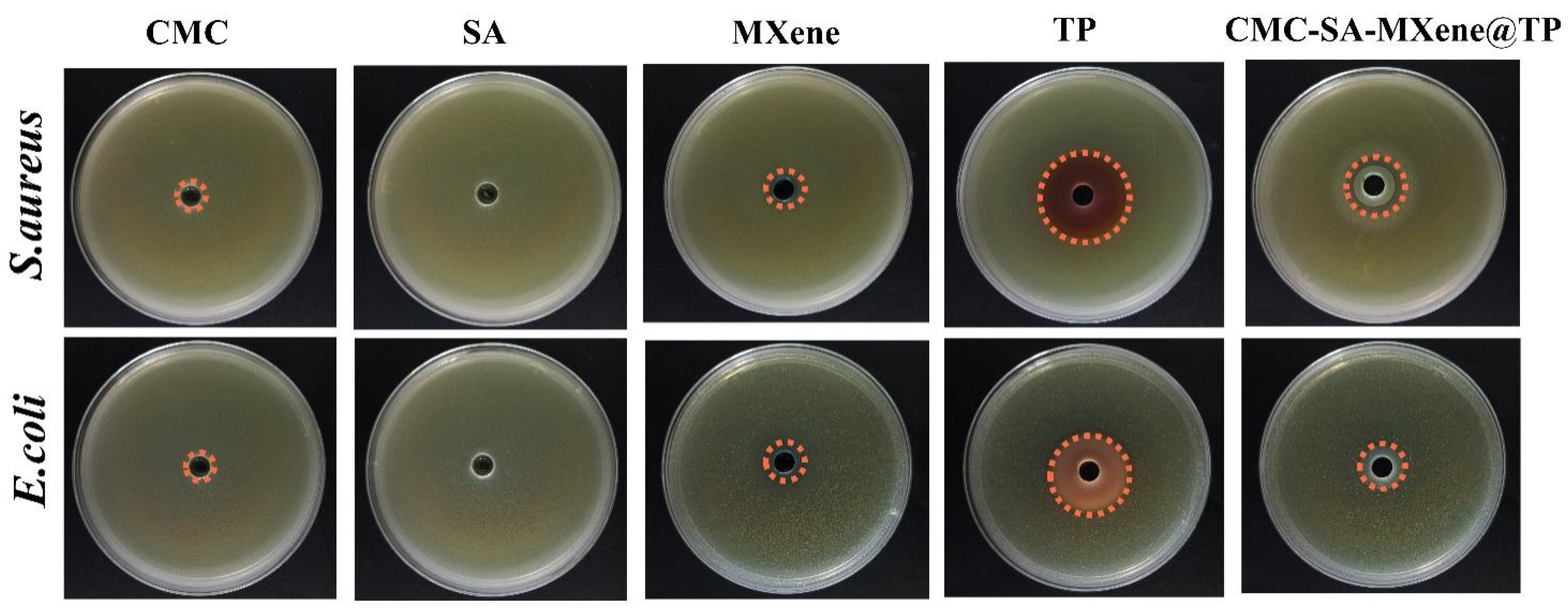

2.5. Antibacterial Activity Analysis

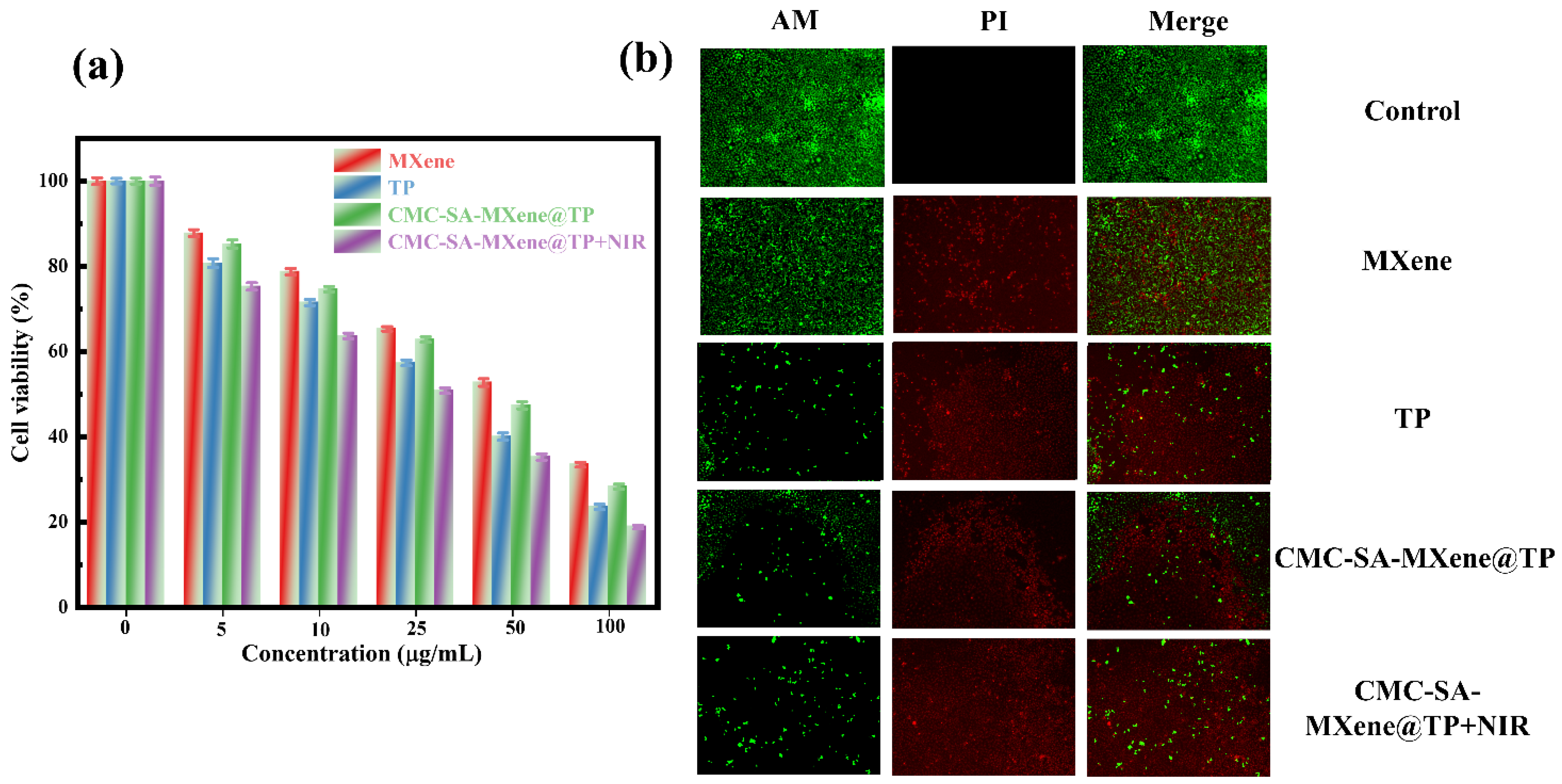

2.6. Cell Cytocompatibility and Toxicity Test

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Fabrication of MXene Nanosheets

4.3. Construction of CMC-SA-MXene@TP Hydrogel Beads

4.4. Characterizations

4.5. Determination of TP Content (TPC)

4.6. TP Release Under pH and NIR Stimuli

4.7. TP Release Kinetics

4.8. DPPH Free Radical Scavenging Activity

4.9. Antibacterial Activity

4.10. Cell Cytocompatibility and Toxicity

4.11. Statistical Analysis

4.12. Comparative Application of SA/MXene Hybrid Systems in the Biomedical Field

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ma, M.; Gu, M.; Zhang, S.; Yuan, Y. Effect of tea polyphenols on chitosan packaging for food preservation: Physicochemical properties, bioactivity, and nutrition. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 259, 129267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Chen, Z.; Chen, H.; Chen, K.; Tao, W.; Ouyang, X.-K.; Mei, L.; Zeng, X. Polyphenol-based hydrogels: Pyramid evolution from crosslinked structures to biomedical applications and the reverse design. Bioact. Mater. 2022, 17, 49–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraga, C.G.; Croft, K.D.; Kennedy, D.O.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A. The effects of polyphenols and other bioactives on human health. Food Fun 2019, 10, 514–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, J.; Shang, M.; Li, X.; Sang, S.; Chen, L.; Long, J.; Jiao, A.; Ji, H.; Jin, Z.; Qiu, C. Health benefits, mechanisms of interaction with food components, and delivery of tea polyphenols: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. 2024, 64, 12487–12499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Ma, M.; Li, C.; Luo, L. Stability of tea polyphenols solution with different pH at different temperatures. Int. J. Food Prop. 2017, 20, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wan, H.; Hu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Li, X.; Song, W.; Chen, X. Physicochemical and colon cancer cell inhibitory properties of theabrownins prepared by weak alkali oxidation of tea polyphenols. Plant Food. Hum. Nutr. 2022, 77, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Li, H.; Zhang, L.; Ping, Y.; Wang, Q.; Fang, X.; Zhao, B.; Zhang, L. Construction and microencapsulation of tea polyphenols W1/O/W2 double emulsion based on modified gluten (MEG). Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 290, 139050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Song, J.; Wang, H.; Wang, C.; Liu, M.; Li, C. Preparation, process optimization, and performance study of tea polyphenol-sodium alginate/ethyl cellulose composite microcapsules for green slow-release formaldehyde capture agent. J. Macromol. Sci. A 2025, 62, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Song, J.; Liu, C.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Han, M.; Liang, J.; Gao, Z. Corn starch/β-Cyclodextrin composite nanoparticles for encapsulation of tea polyphenol and development of oral targeted delivery systems with pH-responsive properties. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 151, 109823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jara-Quijada, E.; Pérez-Won, M.; Tabilo-Munizaga, G.; Lemus-Mondaca, R.; González-Cavieres, L.; Palma-Acevedo, A.; Herrera-Lavados, C. Liposomes loaded with green tea polyphenols-optimization, characterization, and release kinetics under conventional heating and pulsed electric fields. Food Bioprocess Tech. 2024, 17, 396–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Kelly, A.L.; Miao, S. Emulsion-based encapsulation and delivery systems for polyphenols. Trends in Food Sci. Tech. 2016, 47, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, C.; Liu, G.; Ping, Y.; Yang, K.; Tan, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, G.; Huang, X.; Xu, D. A comprehensive review of nano-delivery system for tea polyphenols: Construction, applications, and challenges. Food Chem. X 2023, 17, 100571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Duan, M.; Hou, D.; Chen, X.; Shi, J.; Zhou, W. Fabrication and characterization of Ca (II)-alginate-based beads combined with different polysaccharides as vehicles for delivery, release and storage of tea polyphenols. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 112, 106274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.; Li, W.; Sun, J.; Jia, L.; Guan, Q.; Guo, Y.; Wang, Y. A review on plant polysaccharide based on drug delivery system for construction and application, with emphasis on traditional Chinese medicine polysaccharide. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 211, 711–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, P.; Guo, L.; Huang, L.; Li, X.; Gao, W. Naturally and chemically acetylated polysaccharides: Structural characteristics, synthesis, activities, and applications in the delivery system: A review. Carbohyd. Polym. 2023, 313, 120746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, K.; Li, P.; Huang, X.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Zhu, D.; Luo, B. Recent advancements in magnetic starch-based composites for biomedical applications: A review. Carbohyd. Polym. 2025, 362, 123689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abka-Khajouei, R.; Tounsi, L.; Shahabi, N.; Patel, A.K.; Abdelkafi, S.; Michaud, P. Structures, properties and applications of alginates. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Jiang, S.; Zhao, D.; Diao, Y.; Liu, X.; Chen, J.; Liu, J.; Yang, H. Ionic organohydrogel with long-term environmental stability and multifunctionality based on PAM and sodium alginate. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 485, 149810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarova, A.O.; Derkach, S.R.; Khair, T.; Kazantseva, M.A.; Zuev, Y.F.; Zueva, O.S. Ion-induced polysaccharide gelation: Peculiarities of alginate egg-box association with different divalent cations. Polymers 2023, 15, 1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadach, B.; Świetlik, W.; Froelich, A. Sodium alginate as a pharmaceutical excipient: Novel applications of a well-known polymer. J. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 111, 1250–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabelo, R.S.; Tavares, G.M.; Prata, A.S.; Hubinger, M.D. Complexation of chitosan with gum Arabic, sodium alginate and κ-carrageenan: Effects of pH, polymer ratio and salt concentration. Carbohyd. Polym. 2019, 223, 115120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Q.; Ma, H.; Liu, Z.; Pan, C.; Zuo, X.; Cheng, S.; Li, K.; Lv, J.; Guo, A. Carboxymethyl chitosan: Synthesis, functional properties, and applications in sustainable food packaging material. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2024, 23, e70061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, H.; Huang, X.; Du, X.; Mo, L.; Ma, C.; Wang, H. Facile synthesis of pH-responsive sodium alginate/carboxymethyl chitosan hydrogel beads promoted by hydrogen bond. Carbohyd. Polym. 2022, 278, 118993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shariatinia, Z. Carboxymethyl chitosan: Properties and biomedical applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 120, 1406–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; He, J. Emerging roles and advanced applications of carboxymethyl chitosan in food technology: A review. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 164, 111197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, K.; Li, P.; Zhang, B.; Liu, S.; Zhao, X.; Kou, L.; Xu, W.; Guo, X.; Li, J. Insights on updates in sodium alginate/MXenes composites as the designer matrix for various applications: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 269, 132032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakkan, T.; Punyodom, W.; Meepowpan, P.; Srithep, Y.; Thanakkasaranee, S.; Rachtanapun, P.; Jantanasakulwong, K.; Worajittiphon, P. Cellulose nanofiber-reinforced chitosan/PVA/MXene (Ti3C2Tx) membrane: Enhanced multifunctional performance and non-cytotoxicity for drug delivery. Carbohyd. Polym. Tech. 2025, 9, 100712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, K.; Li, P.; Huang, X.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Zhu, D.; Luo, B. pH/NIR light-responsive carboxymethyl starch/sodium alginate/MXene hydrogel beads for doxorubicin delivery. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 321, 146306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stribiţcaia, E.; Krop, E.M.; Lewin, R.; Holmes, M.; Sarkar, A. Tribology and rheology of bead-layered hydrogels: Influence of bead size on sensory perception. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 104, 105692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurzęda, B.; Boulanger, N.; Nordenström, A.; Dejoie, C.; Talyzin, A.V. Pristine MXene: In situ XRD study of MAX phase etching with HCl+ LiF solution. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2408448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Usman, K.A.S.; Judicpa, M.A.N.; Hegh, D.; Lynch, P.A.; Razal, J.M. Applications of X-ray-based characterization in MXene research. Small Methods 2023, 7, 2201527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halim, J.; Kota, S.; Lukatskaya, M.R.; Naguib, M.; Zhao, M.Q.; Moon, E.J.; Pitock, J.; Nanda, J.; May, S.J.; Gogotsi, Y. Synthesis and characterization of 2D molybdenum carbide (MXene). Adv. Funct. Mater. 2016, 26, 3118–3127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firestein, K.L.; von Treifeldt, J.E.; Kvashnin, D.G.; Fernando, J.F.; Zhang, C.; Kvashnin, A.G.; Podryabinkin, E.V.; Shapeev, A.V.; Siriwardena, D.P.; Sorokin, P.B. Young’s modulus and tensile strength of Ti3C2 MXene nanosheets as revealed by in situ TEM probing, AFM nanomechanical mapping, and theoretical calculations. Nano Lett. 2020, 20, 5900–5908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Abreu, F.R.; Campana-Filho, S.P. Characteristics and properties of carboxymethylchitosan. Carbohyd. Polym. 2009, 75, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derkach, S.R.; Voron’ko, N.G.; Sokolan, N.I.; Kolotova, D.S.; Kuchina, Y.A. Interactions between gelatin and sodium alginate: UV and FTIR studies. J. Disper. Sci. Technol. 2020, 41, 690–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Liu, X.; Liu, J.; Fan, H.; Ren, J.; Liu, H.; Liu, T. Study on the structure and adsorption characteristics of the complex of modified Lentinus edodes stalks dietary fiber and tea polyphenol. Food Chem. 2025, 468, 142321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, T.; Zhang, D.; Bugallo, D.; Shevchuk, K.; Downes, M.; Valurouthu, G.; Inman, A.; Chacon, B.; Zhang, T.; Shuck, C.E. Fourier-transform infrared spectral library of MXenes. Chem. Mater. 2024, 36, 8437–8446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Li, X.; Wu, M.; Chen, C.; Hu, Z.; Zhao, M.; Xue, Y. MXene/polyaniline/sodium alginate composite gel: Adsorption and regeneration studies and application in Cu(II) and Hg(II) removal. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 353, 128298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Li, Y.; Chen, K.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H. Enhanced physical and antimicrobial properties of alginate/chitosan composite aerogels based on electrostatic interactions and noncovalent crosslinking. Carbohyd. Polym. 2021, 266, 118102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathis, T.S.; Maleski, K.; Goad, A.; Sarycheva, A.; Anayee, M.; Foucher, A.C.; Hantanasirisakul, K.; Shuck, C.E.; Stach, E.A.; Gogotsi, Y. Modified MAX phase synthesis for environmentally stable and highly conductive Ti3C2 MXene. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 6420–6429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.K.; Deshpande, A.P.; Kumar, R. Rheological and dielectric behavior of sodium carboxymethyl cellulose (NaCMC)/Ca2+ and esterified NaCMC/Ca2+ hydrogels: Correlating microstructure and dynamics with properties. Carbohyd. Polym. 2024, 335, 122049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saadatkhah, N.; Carillo Garcia, A.; Ackermann, S.; Leclerc, P.; Latifi, M.; Samih, S.; Patience, G.S.; Chaouki, J. Experimental methods in chemical engineering: Thermogravimetric analysis-TGA. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2020, 98, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Zhang, Z.; Guo, Z.; Zhou, J.; Wang, K.; Wang, J. Construction of carboxymethyl chitosan@ sodium oxide alginate aerogel for efficient adsorption of malachite green. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2023, 63, 3443–3458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Sun, L.; Gu, Z.; Li, W.; Guo, L.; Ma, S.; Guo, L.; Zhang, W.; Han, B.; Chang, J. N-carboxymethyl chitosan/sodium alginate composite hydrogel loading plasmid DNA as a promising gene activated matrix for in-situ burn wound treatment. Bioact. Mater. 2022, 15, 330–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, D.; Deng, D.; Lv, J.; Zhang, W.; Tian, H.; Zhang, X.; Wu, M.; Zhao, Y. A novel macroporous carboxymethyl chitosan/sodium alginate sponge dressing capable of rapid hemostasis and drug delivery. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 278, 134943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Chen, D.; Li, W.; Wang, B.; Hu, J. Highly sensitive and environmentally stable conductive eutectogels for flexible wearable sensors based on sodium alginate/poly (vinyl alcohol)/MXene. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 312, 143931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, D.; Pan, Y.; Cai, P.; Xiao, H. Redox/pH dual-responsive sodium alginate/cassava starch composite hydrogel beads for slow release of insecticides. React. Funct. Polym. 2025, 215, 106389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.B.; Park, J.M.; Park, R.; Choi, H.E.; Hong, S.W.; Kim, K.S. Synergistic chemo-photothermal treatment via MXene-encapsulated nanoparticles for targeted melanoma therapy. J. Control. Release 2025, 382, 113729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askarizadeh, M.; Esfandiari, N.; Honarvar, B.; Sajadian, S.A.; Azdarpour, A. Kinetic modeling to explain the release of medicine from drug delivery systems. ChemBioEng Rev. 2023, 10, 1006–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaiwong, N.; Leelapornpisid, P.; Jantanasakulwong, K.; Rachtanapun, P.; Seesuriyachan, P.; Sakdatorn, V.; Leksawasdi, N.; Phimolsiripol, Y. Antioxidant and moisturizing properties of carboxymethyl chitosan with different molecular weights. Polymers 2020, 12, 1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Z.; Wang, S.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhao, L.; Ge, Q.; Zhang, J.Z. Scavenging activity and reaction mechanism of Ti3C2Tx MXene as a novel free radical scavenger. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 16555–16561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Zhong, Y.; Duan, Y.; Chen, Q.; Li, F. Antioxidant mechanism of tea polyphenols and its impact on health benefits. Anim. Nutr. 2020, 6, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Xie, Y.; Chen, X.; Li, H.; Lu, Y.; Yu, H.; Zheng, D. O-carboxymethyl chitosan in biomedicine: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 275, 133465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandian, M.; Selvaprithviraj, V.; Pradeep, A.; Rangasamy, J. In-situ silver nanoparticles incorporated N, O-carboxymethyl chitosan based adhesive, self-healing, conductive, antibacterial and anti-biofilm hydrogel. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 188, 501–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasool, K.; Helal, M.; Ali, A.; Ren, C.E.; Gogotsi, Y.; Mahmoud, K.A. Antibacterial activity of Ti3C2Tx MXene. ACS Nano 2016, 10, 3674–3684. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Xu, D.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, R.; Wu, Z.; Weng, P. Antimicrobial effect of tea polyphenols against foodborne pathogens: A review. J. Food Protect 2021, 84, 1801–1808. [Google Scholar]

- Hausig-Punke, F.; Richter, F.; Hoernke, M.; Brendel, J.C.; Traeger, A. Tracking the endosomal escape: A closer look at calcein and related reporters. Macromol. Biosci. 2022, 22, 2200167. [Google Scholar]

- Hafner, M.; Niepel, M.; Chung, M.; Sorger, P.K. Growth rate inhibition metrics correct for confounders in measuring sensitivity to cancer drugs. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, B.; Anwar, A.; Shahabuddin, S.; Mohan, G.; Saidur, R.; Aslfattahi, N.; Sridewi, N. A comparative study of cytotoxicity of PPG and PEG surface-modified 2-D Ti3C2 MXene flakes on human cancer cells and their photothermal response. Materials 2021, 14, 4370. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Pan, L.; Tang, H.; Du, F.; Guo, Y.; Qiu, T.; Yang, J. Synthesis of two-dimensional Ti3C2Tx MXene using HCl+ LiF etchant: Enhanced exfoliation and delamination. J. Alloy. Compd. 2017, 695, 818–826. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Yin, J.; Yang, T.; Li, K.; Wei, L.; Li, J.; He, W. Hydrogel beads based on carboxymethyl cassava starch/alginate enriched with MgFe2O4 nanoparticles for controlling drug release. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 220, 573–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benlloch-Tinoco, M.; Gentile, P.; Taylor, L.; Girón-Hernández, J. Alginate edible films as delivery systems for green tea polyphenols. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 158, 110518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Yu, S.; Lin, D.; Wu, Z.; Xu, J.; Zhang, J.; Ding, Z.; Miao, Y.; Liu, T.; Chen, T. Preparation, characterization, and release behavior of doxorubicin hydrochloride from dual cross-linked chitosan/alginate hydrogel beads. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2020, 3, 3057–3065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandl, F.; Kastner, F.; Gschwind, R.M.; Blunk, T.; Teßmar, J.; Göpferich, A. Hydrogel-based drug delivery systems: Comparison of drug diffusivity and release kinetics. J. Control. Release 2010, 142, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Niu, L.; Sun, C.; Tu, J.; Yu, L.; Xiao, J. Collagen hydrolysates improve the efficiency of sodium alginate-encapsulated tea polyphenols in beads and the storage stability after commercial sterilization. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 231, 123314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Zhao, D.; Wang, B.; Bai, S.; Fan, B.; Zhang, L.; Wang, F. Adsorption and in vitro controlled–release properties of a soybean cellulose nanocrystal/polyacrylamide–based hydrogel as a carrier for different polyphenols. Food Chem. 2025, 479, 143843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahmasebi, S.; Farmanbordar, H.; Mohammadi, R. Synthesis of magnetic bio-nanocomposite hydrogel beads based on sodium alginate and β-cyclodextrin: Potential pH-responsive oral delivery anticancer systems for colorectal cancer. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 305, 140748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Wei, S.; He, F.; Li, Z.; Wang, H.-H.; Huang, Y.; Nie, Z. Near-infrared light-controllable MXene hydrogel for tunable on-demand release of therapeutic proteins. Acta Biomater. 2021, 130, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Sun, R. Fabrication and properties of multifunctional sodium alginate/MXene/nano-hydroxyapatite hydrogel for potential bone defect repair. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 36, 913–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Kim, J.-U.; Kim, S.; Hwang, N.S.; Kim, H.D. Sprayable Ti3C2 MXene hydrogel for wound healing and drug release system. Mater. Today Bio 2023, 23, 100881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Cao, W.; Liu, Y.; Liu, H.; Ru, J.; Yin, M.; Luo, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, F. Hydrogel microspheres encapsulating lysozyme/MXene for photothermally enhanced antibacterial activity and infected wound healing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 279, 135527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, K.; Zheng, Y.; He, J.; Huang, Y.; Gao, J.; Chen, X.; Wang, T.; Zhou, H.; Wen, J.; et al. A dual-polysaccharide (carboxylated chitosan-carboxymethyl cellulose sodium) gastrointestinal dynamic response in situ hydrogel for optimized oral targeted inflammatory bowel disease therapy. Carbohyd. Polym. 2025, 363, 123704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Samples | Additions of TP(g) | Loading Capacity (LC%) |

|---|---|---|

| CMC-SA-MXene@TP-1 | 0.25 | 15.68 ± 0.72 a |

| CMC-SA-MXene@TP-2 | 0.50 | 34.43 ± 0.87 b |

| CMC-SA-MXene@TP-3 | 0.75 | 37.02 ± 0.98 c |

| Samples | E. coli | S. aureus |

|---|---|---|

| CMC | 7.25 ± 0.32 a | 7.68 ± 0.41 b |

| MXene | 11.03 ± 0.58 c | 12.72 ± 0.78 c |

| TP | 26.58 ± 1.42 d | 31.33 ± 1.74 e |

| CMC-SA-MXene@TP | 15.31 ± 0.86 c | 19.29 ± 0.93 d |

| Samples | Model Drug | Drug Loading Capacity (%) | Antibacterial Properties | Experimental Cells | Cytotoxicity (IC50 Concentration) | Drug Release Mechanism | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sodium alginate/MXene/nano-hydroxyapatite hydrogel (SA/MXene/nHAp) | Dorubixin | NR | E. coli S. aureus | MC3T3-E1 | NR | NR | [69] |

| Ciprofloxacin (CIP)-loaded MXene/sodium alginate (SA) hydrogel (CIP-MX@Gel) | Ciprofloxacin | NR | E. coli S. aureus | HDF | NR | NR | [70] |

| Alginate-based hydrogel microspheres containing lysozyme and MXene (i-Lyso@Alg) | Lysozyme | NR | S. aureus | NIH 3T3 | NR | NR | [71] |

| Cross-linker-independent oral in situ hydrogel (CCS/CMC-Na) | Chlorogenic acid | NR | Lactobacillus, Muribaculum intestinale, Lactobacillus gasseri, Bacteroides_sp_ HF-5287, Phocaeicola vulgatus, E. coli. | Caco-2 | NR | NR | [72] |

| Carboxymethyl Chitosan/Sodium Alginate/MXene Hydrogel beads (CMC-SA-MXene@TP) | TP | 37.02% | E. coli S. aureus | HL-7702 HepG2 | 26.51 μg/mL | Ritger–Peppas model | This study |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fang, K.; Li, P.; Wang, H.; Huang, X.; Li, Y.; Luo, B. Smart pH/Near-Infrared Light-Responsive Carboxymethyl Chitosan/Sodium Alginate/MXene Hydrogel Beads for Targeted Tea Polyphenols Delivery. Gels 2025, 11, 1009. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11121009

Fang K, Li P, Wang H, Huang X, Li Y, Luo B. Smart pH/Near-Infrared Light-Responsive Carboxymethyl Chitosan/Sodium Alginate/MXene Hydrogel Beads for Targeted Tea Polyphenols Delivery. Gels. 2025; 11(12):1009. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11121009

Chicago/Turabian StyleFang, Kun, Pei Li, Hanbing Wang, Xiangrui Huang, Yihan Li, and Bo Luo. 2025. "Smart pH/Near-Infrared Light-Responsive Carboxymethyl Chitosan/Sodium Alginate/MXene Hydrogel Beads for Targeted Tea Polyphenols Delivery" Gels 11, no. 12: 1009. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11121009

APA StyleFang, K., Li, P., Wang, H., Huang, X., Li, Y., & Luo, B. (2025). Smart pH/Near-Infrared Light-Responsive Carboxymethyl Chitosan/Sodium Alginate/MXene Hydrogel Beads for Targeted Tea Polyphenols Delivery. Gels, 11(12), 1009. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11121009