Eco-Friendly Hydrogels from Natural Gums and Cellulose Citrate: Formulations and Properties

Abstract

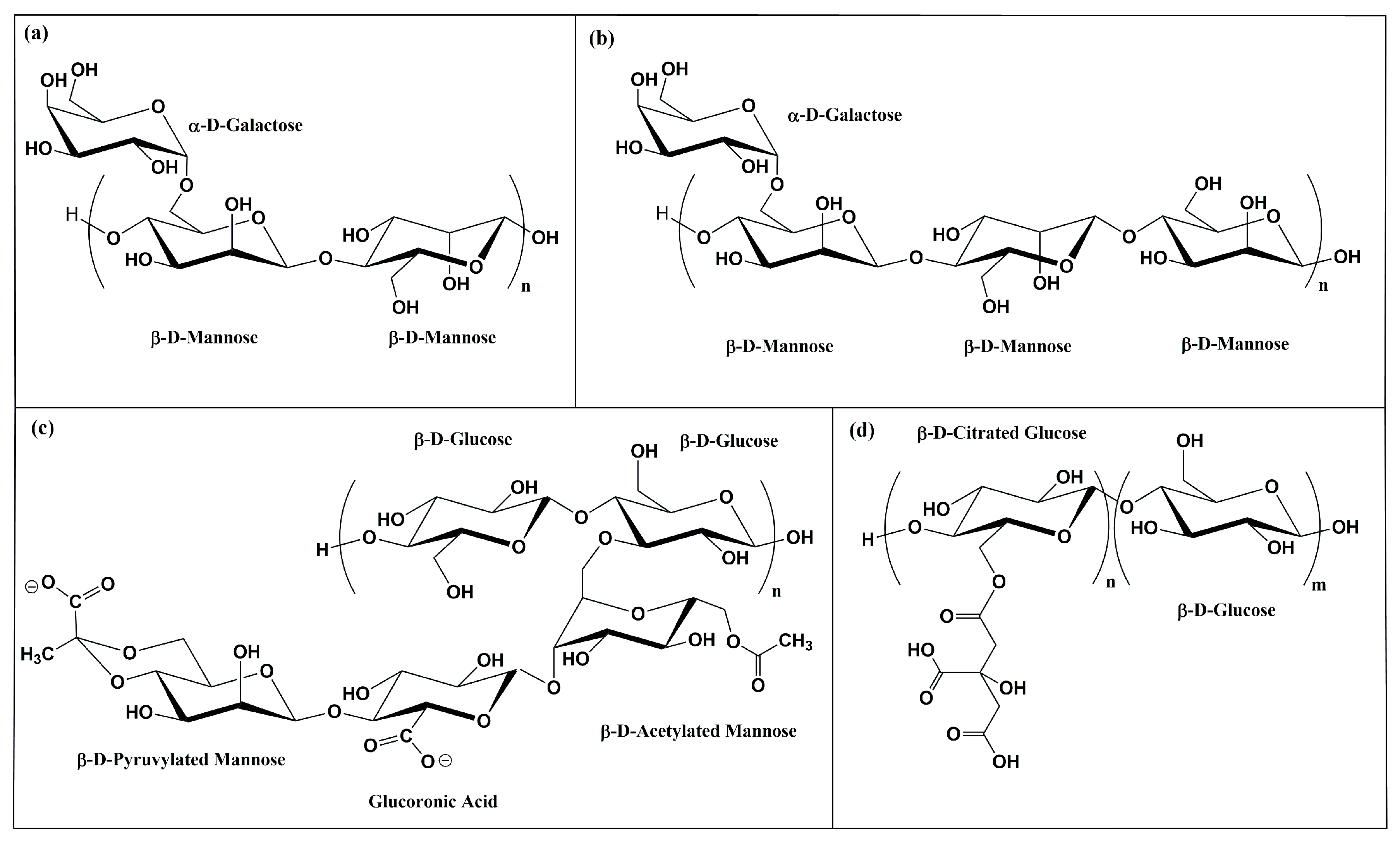

1. Introduction

- (i.)

- Solubilization: CC was dissolved in water to ensure homogeneous mixing with the gums. [27].

- (ii.)

- (iii.)

- Biostability: to suppress microbial growth (e.g., yeast), allowing storage of the hydrogels for months, even at room temperature.

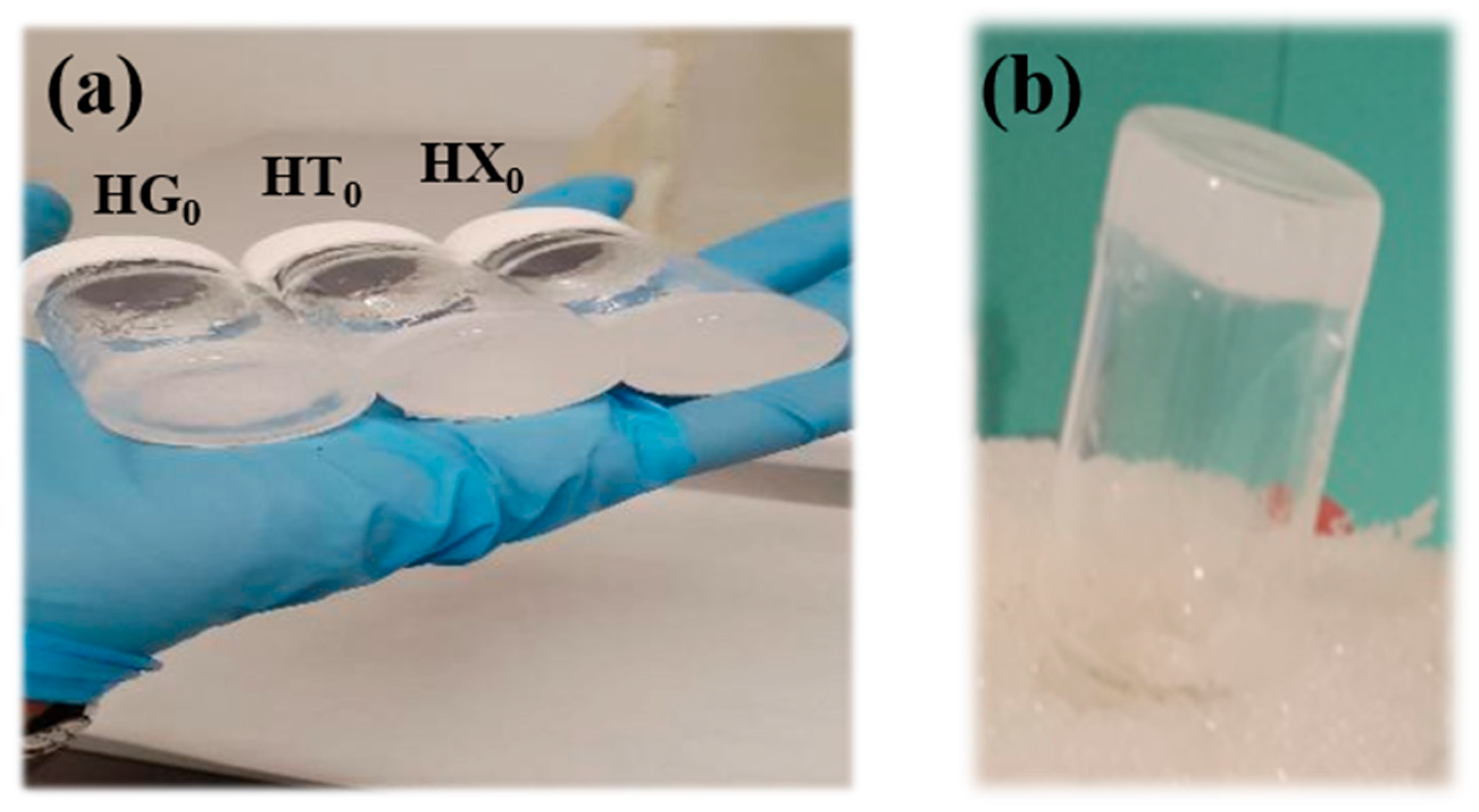

2. Results and Discussion

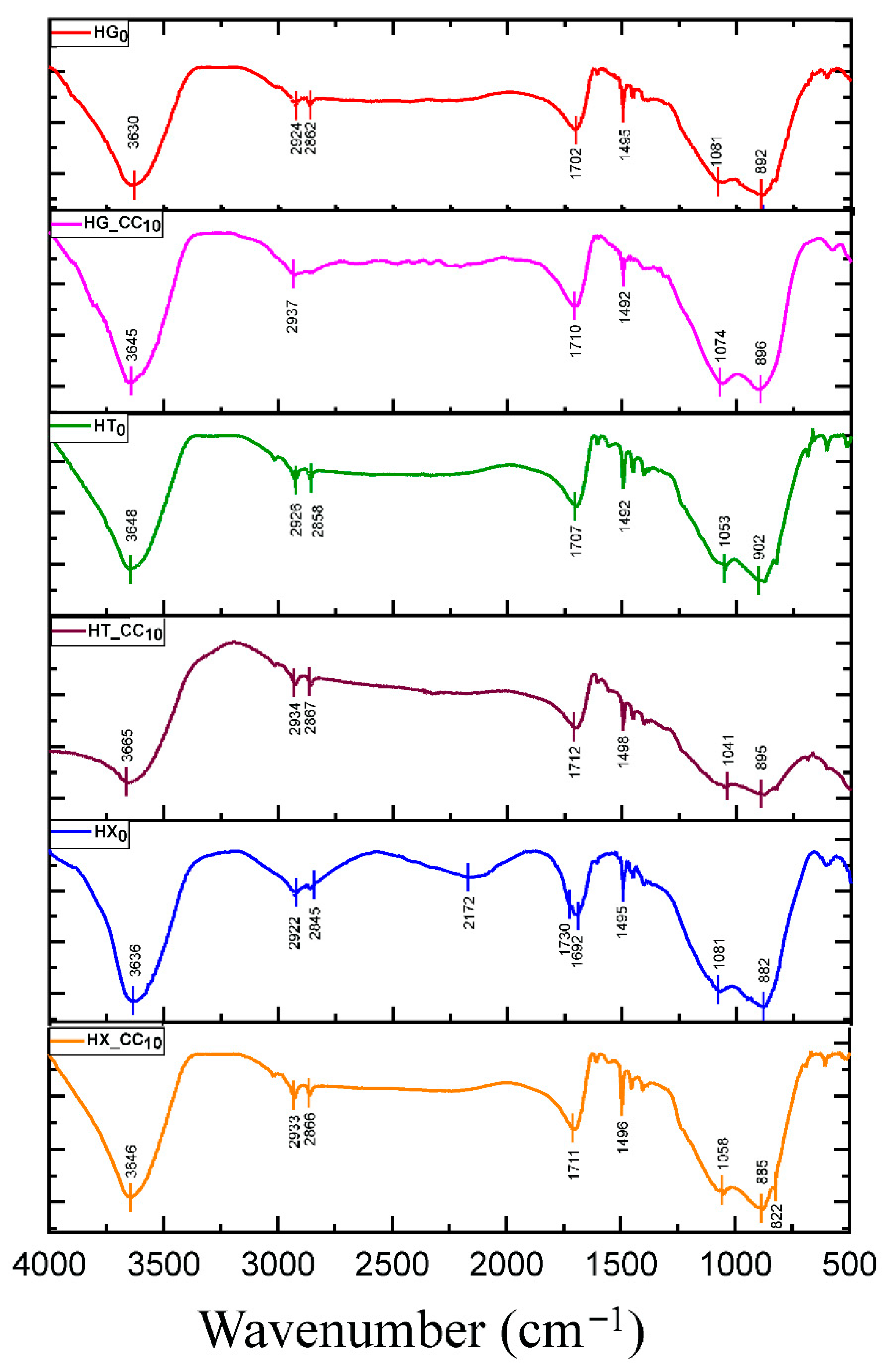

2.1. FT-IR Spectral Analysis of the Hydrogels

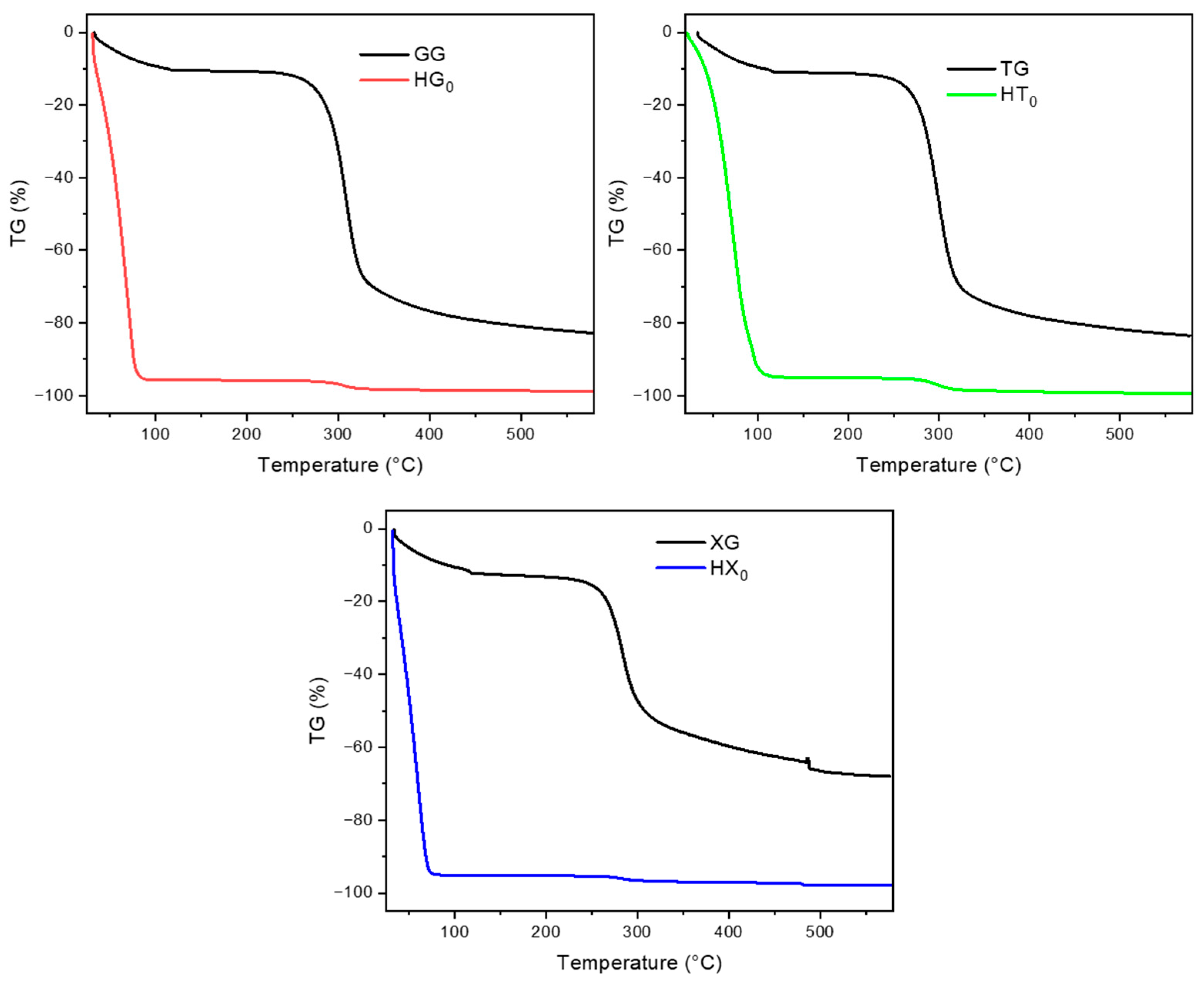

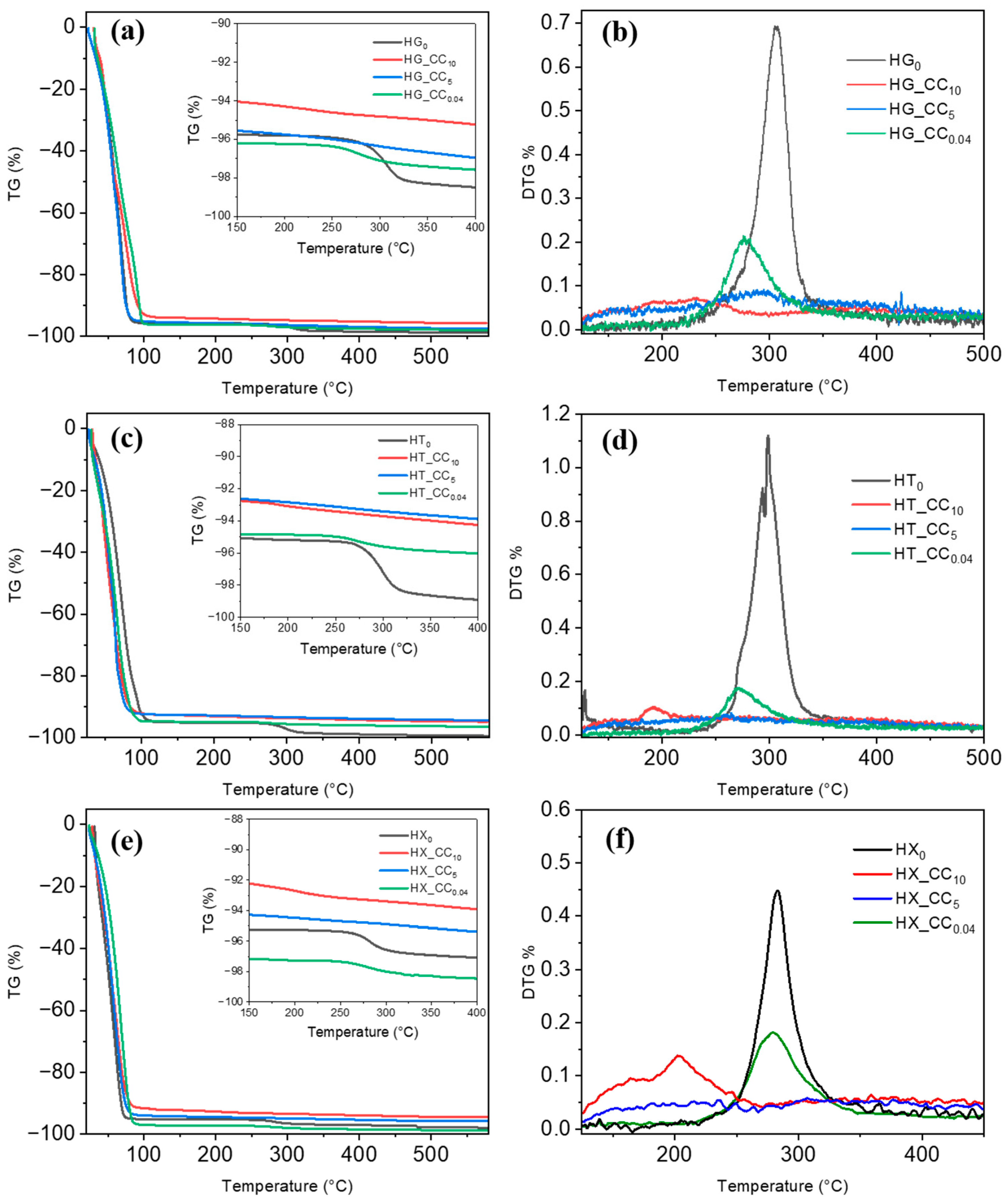

2.2. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

2.2.1. Pure Gum Hydrogels (HG, HT, and HX)

2.2.2. Cellulose Citrate Powder

2.2.3. Composite Hydrogels (HG_CC, HT_CC, and HX_CC Series)

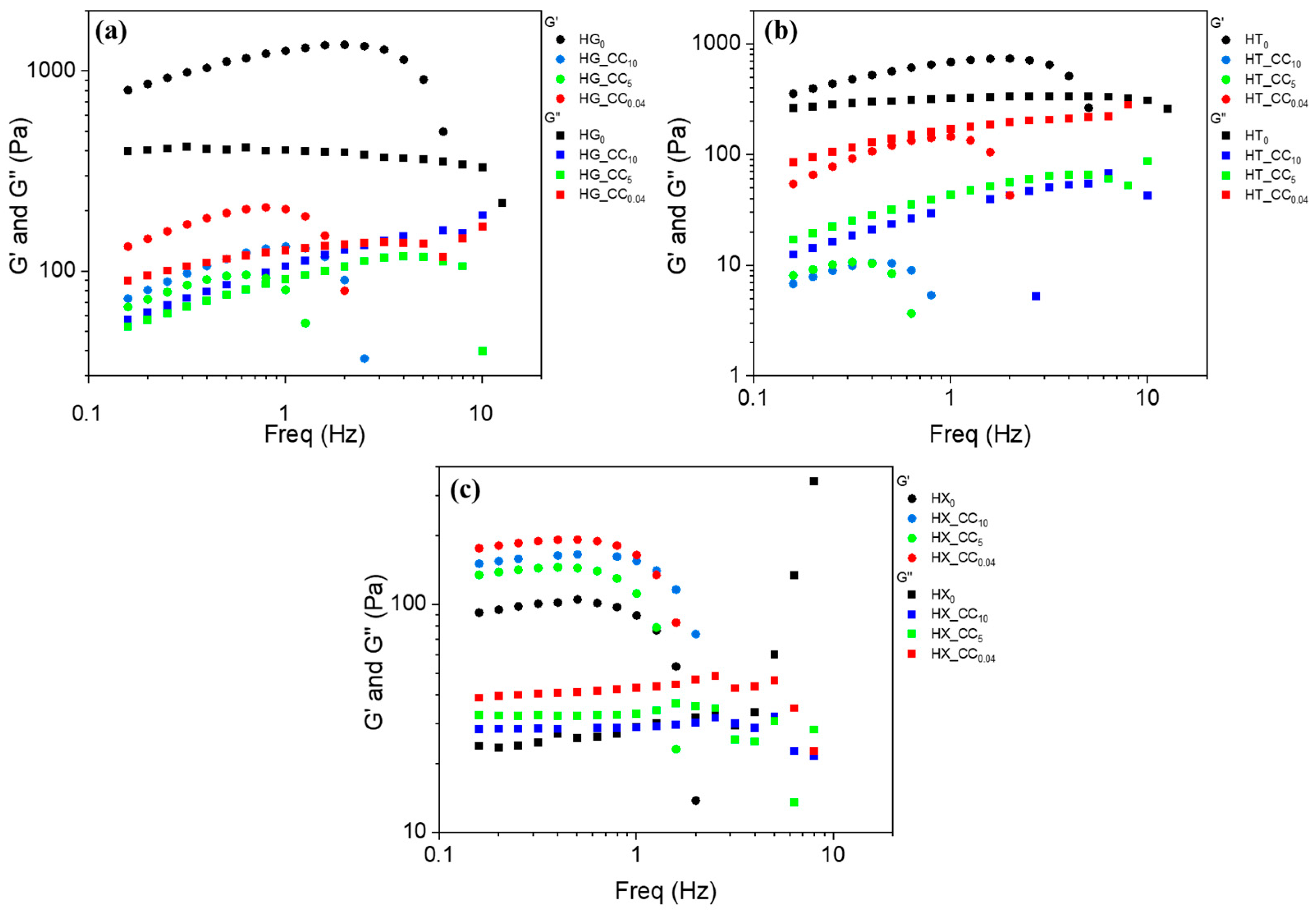

2.3. Viscoelastic Properties

2.3.1. Gum Hydrogels and Their Composites with Cellulose Citrate at 25 °C

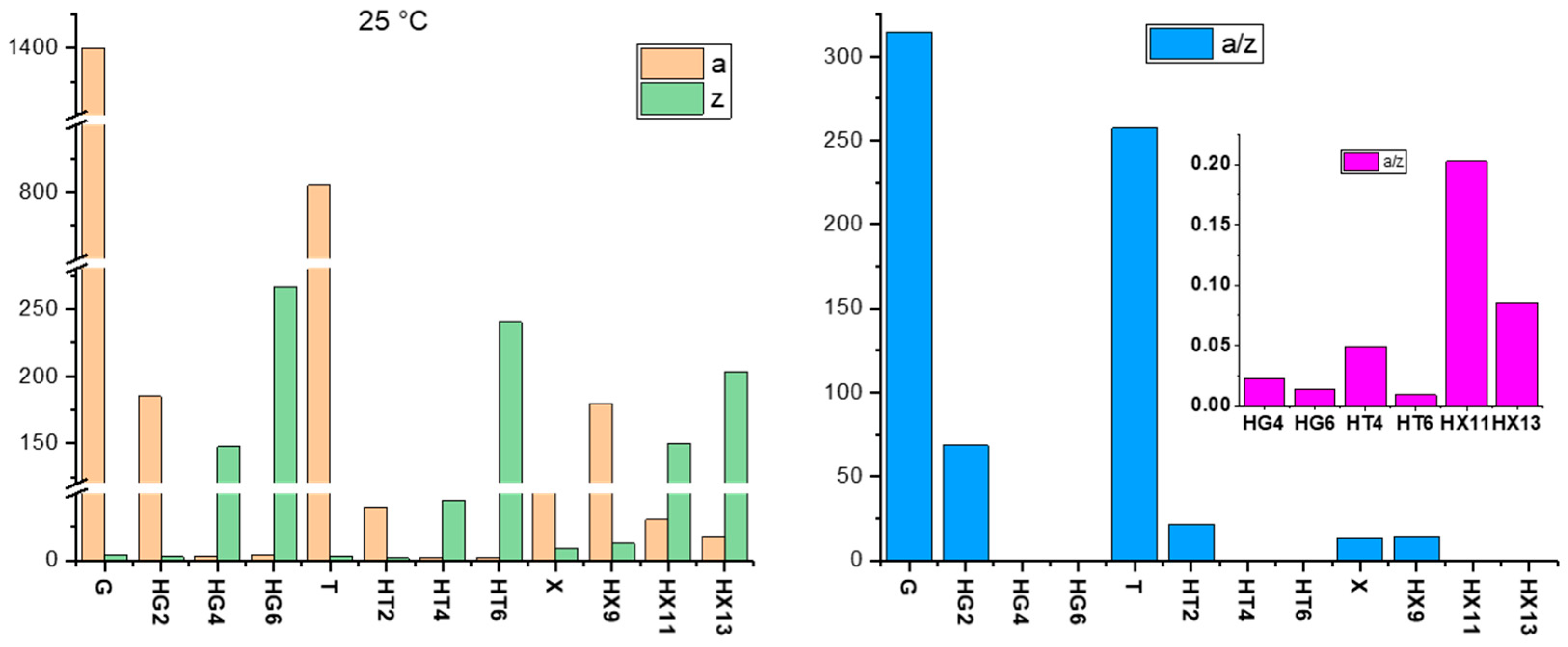

Quantitative Rheological Evaluation Using the Weak Gel Model

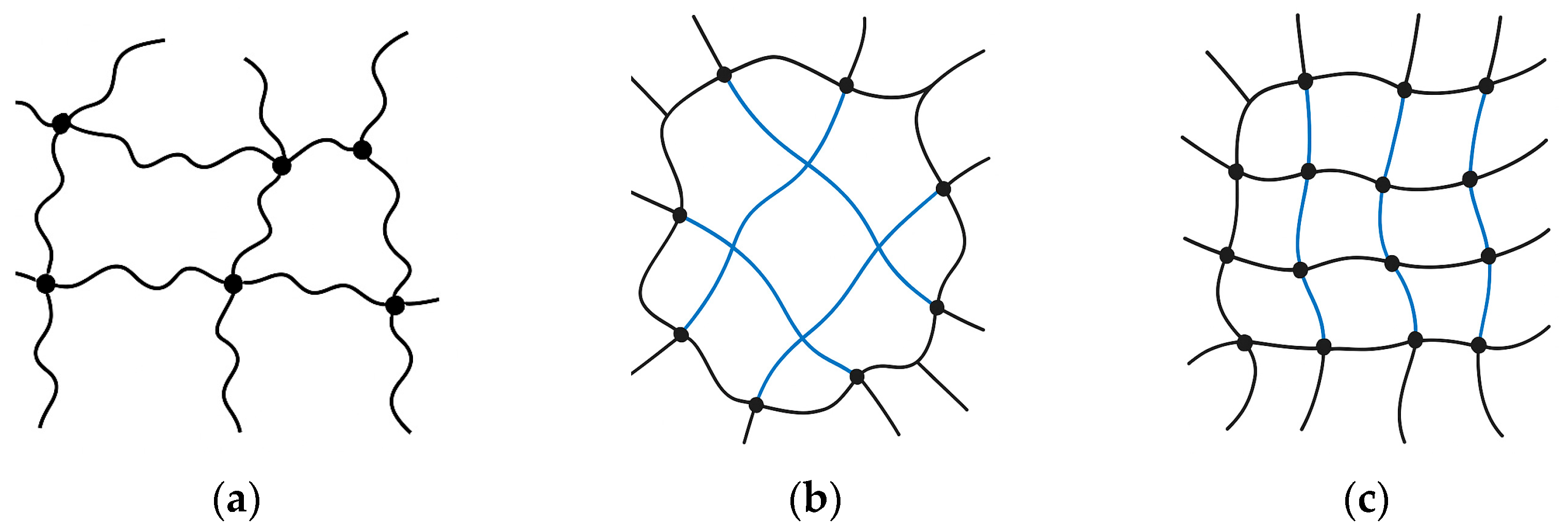

Crosslinking Density (νe) of Natural Gum-Based Hydrogels and the Effect of Citrated Cellulose Incorporation

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Hydrogels Preparation

- 10% NaOH solution: to completely dissolve CC.

- 5% NaOH solution: to prepare a CC suspension.

- Ultrapure water containing 0.04% NaOH: in this case CC was first dispersed and sonicated to improve dispersion. The minimal amount of base slightly increased the pH, but was necessary to inhibit microbial growth during gelation.

| Gum Type | Marked Name | Gum (w/w)% | Cellulose Citrate (w/w)% | NaOH (w/w)% | a Gel/Liquid Phase Transition Temperature TG/L (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guar | HG0 | - | - | 70–80 °C | |

| HG_CC10 | 2.25 | 0.075 | 10 | 70 | |

| HG_CC5 | 5 | 70 | |||

| HG_CC0.04 | 0.04 | 70 | |||

| Tara | HT0 | - | - | 60–70 °C | |

| HT_CC10 | 2.25 | 0.075 | 10 | 50 | |

| HT_CC5 | 5 | 50 | |||

| HT_CC0.04 | 0.04 | 50 | |||

| Xanthan | HX0 | - | - | 80 °C | |

| HX_CC10 | 2.25 | 0.075 | 10 | 80 °C | |

| HX_CC5 | 5 | 80 °C | |||

| HX_CC0.04 | 0.04 | 80 °C |

4.3. Characterization of Hydrogels

4.3.1. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR)

4.3.2. Optical Transmittance Measurements

4.3.3. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

4.3.4. Dynamic-Mechanical Analysis/Rheological

4.3.5. Apparent Crosslinking Density Calculation

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Caló, E.; Khutoryanskiy, V.V. Biomedical Applications of Hydrogels: A Review of Patents and Commercial Products. Eur. Polym. J. 2015, 65, 252–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavutsky, A.M.; Bertuzzi, M.A. Formulation and Characterization of Hydrogel Based on Pectin and Brea Gum. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 123, 784–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peppas, N.A.; Bures, P.; Leobandung, W.; Ichikawa, H. Hydrogels in Pharmaceutical Formulations. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2000, 50, 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demitri, C.; Del Sole, R.; Scalera, F.; Sannino, A.; Vasapollo, G.; Maffezzoli, A.; Ambrosio, L.; Nicolais, L. Novel Superabsorbent Cellulose-Based Hydrogels Crosslinked with Citric Acid. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2008, 110, 2453–2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, E.M. Hydrogel: Preparation, Characterization, and Applications: A Review. J. Adv. Res. 2015, 6, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennink, W.E.; van Nostrum, C.F. Novel Crosslinking Methods to Design Hydrogels. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2012, 64, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, M.F.; Hanif, M.; Ranjha, N.M. Methods of Synthesis of Hydrogels … A Review. Saudi Pharm. J. 2016, 24, 554–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Ahmed, S. Recent Advances in Edible Polymer Based Hydrogels as a Sustainable Alternative to Conventional Polymers. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 6940–6967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Ahmad, M.; Manzoor, K.; Purwar, R.; Ikram, S. A Review on Latest Innovations in Natural Gums Based Hydrogels: Preparations & Applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 136, 870–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wanniarachchi, P.C.; Paranagama, I.T.; Idangodage, P.A.; Nallaperuma, B.; Samarasinghe, T.T.; Jayathilake, C. Natural Polymer-Based Hydrogels: Types, Functionality, Food Applications, Environmental Significance and Future Perspectives: An Updated Review. Food Biomacromol. 2025, 2, 84–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussinovitch, A. Plant Gum Exudates of the World: Sources, Distribution, Properties, and Applications; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0-429-15046-3. [Google Scholar]

- Olivas, G.I.I.; Barbosa-Cánovas, G. Edible Films and Coatings for Fruits and Vegetables. In Edible Films and Coatings for Food Applications; Huber, K.C., Embuscado, M.E., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 211–244. ISBN 978-0-387-92823-4. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Cui, W.; Eskin, N.A.M.; Goff, H.D. Rheological Investigation of Synergistic Interactions between Galactomannans and Non-Pectic Polysaccharide Fraction from Water Soluble Yellow Mustard Mucilage. Carbohydr. Polym. 2009, 78, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vendruscolo, C.W.; Ferrero, C.; Pineda, E.A.G.; Silveira, J.L.M.; Freitas, R.A.; Jiménez-Castellanos, M.R.; Bresolin, T.M.B. Physicochemical and Mechanical Characterization of Galactomannan from Mimosa scabrella: Effect of Drying Method. Carbohydr. Polym. 2009, 76, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edo, G.I.; Ndudi, W.; Ali, A.M.; Yousif, E.; Jikah, A.N.; Isoje, E.F.; Igbuku, U.A.; Mafe, A.N.; Opiti, R.A.; Madueke, C.J.; et al. Biopolymers: An Inclusive Review. Hybrid Adv. 2025, 9, 100418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumon, M.M.H. Advances in Cellulose-Based Hydrogels: Tunable Swelling Dynamics and Their Versatile Real-Time Applications. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 11688–11729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeo, I.; Olivito, F.; Tursi, A.; Algieri, V.; Beneduci, A.; Chidichimo, G.; Maiuolo, L.; Sicilia, E.; Nino, A.D. Totally Green Cellulose Conversion into Bio-Oil and Cellulose Citrate Using Molten Citric Acid in an Open System: Synthesis, Characterization and Computational Investigation of Reaction Mechanisms. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 34738–34751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Z.; Wang, N.; Du, J. Recent Progress in Cellulose-Based Conductive Hydrogels. Polymers 2025, 17, 1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, T.; Chaturvedi, P.; Llamas-Garro, I.; Velázquez-González, J.S.; Dubey, R.; Mishra, S.K. Smart Materials for Flexible Electronics and Devices: Hydrogel. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 12984–13004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Xu, T.; Liu, K.; Zhu, L.; Miao, C.; Chen, T.; Gao, M.; Wang, J.; Si, C. Modulation and Mechanisms of Cellulose-Based Hydrogels for Flexible Sensors. SusMat 2025, 5, e255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Lv, S.; Mu, Y.; Tong, J.; Liu, L.; He, T.; Zeng, Q.; Wei, D. Applied Research and Recent Advances in the Development of Flexible Sensing Hydrogels from Cellulose: A Review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 281, 136100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinze, T.; El Seoud, O.A.; Koschella, A. Cellulose Esters. In Cellulose Derivatives: Synthesis, Structure, and Properties; Heinze, T., El Seoud, O.A., Koschella, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 293–427. ISBN 978-3-319-73168-1. [Google Scholar]

- Marinho, E. Cellulose: A Comprehensive Review of Its Properties and Applications. Sustain. Chem. Environ. 2025, 11, 100283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Asaki, Y.; Fujiwara, Y.; Wada, T.; Ikura, R.; Sugawara, A.; Konishi, T.; Matsuba, G.; Uetsuji, Y.; Uyama, H.; et al. Tough Citric Acid-Modified Cellulose-Containing Polymer Composites with Three Components Consisting of Movable Cross-Links and Hydrogen Bonds. Polym. J. 2023, 55, 1151–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasution, H.; Harahap, H.; Dalimunthe, N.F.; Ginting, M.H.S.; Jaafar, M.; Tan, O.O.H.; Aruan, H.K.; Herfananda, A.L. Hydrogel and Effects of Crosslinking Agent on Cellulose-Based Hydrogels: A Review. Gels 2022, 8, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Boddu, V.M.; Liu, S.X. Rheological Properties of Hydrogels Produced by Cellulose Derivatives Crosslinked with Citric Acid, Succinic Acid and Sebacic Acid. Cellul. Chem. Technol. 2022, 56, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isogai, A.; Atalla, R.H. Dissolution of Cellulose in Aqueous NaOH Solutions. Cellulose 1998, 5, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulos, N.; Harbottle, D.; Hebden, A.; Goswami, P.; Blackburn, R.S. Kinetic Analysis of Cellulose Acetate/Cellulose II Hybrid Fiber Formation by Alkaline Hydrolysis. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 4936–4942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Liang, Y.; Sun, L.; Yang, Z.; Xu, J.; Dong, D.; Liu, H. Degradation Characteristics of Cellulose Acetate in Different Aqueous Conditions. Polymers 2023, 15, 4505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vulpitta, V.; Corrente, G.A.; Gaudio, D.; Lano, A.; Beneduci, A. Integrated Physicochemical and Chemometric Analysis for the Detection of Tara Gum Adulteration. LWT 2025, 228, 118126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiro, S.; Goes, J.; Moreira, R.; Sombra, A. On the Physico-Chemical and Dielectric Properties of Glutaraldehyde Crosslinked Galactomannan–Collagen Films. Carbohydr. Polym. 2004, 56, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Y.; Skinner, J.L. IR and SFG Vibrational Spectroscopy of the Water Bend in the Bulk Liquid and at the Liquid-Vapor Interface, Respectively. J. Chem. Phys. 2015, 143, 014502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Jiang, F.; Fang, J.; Xu, X.; Chen, F.; Weng, H.; Xiao, Q.; Yang, Q.; Lin, Y.; Xiao, A. Structure, Characterization, and Application of a Novel Thermoreversible Emulsion Gel Fabricated by Citrate Agar. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 277, 134181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhao, L.; Wang, J.; Hu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, P.; Su, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, R.; Ren, F.; et al. Effect of Trisodium Citrate on the Gelation Properties of Casein/Gellan Gum Double Gels Formed at Different Temperature. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2025, 10, 100768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozcan-Yilsay, T.; Lee, W.-J.; Horne, D.; Lucey, J.A. Effect of Trisodium Citrate on Rheological and Physical Properties and Microstructure of Yogurt. J. Dairy Sci. 2007, 90, 1644–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berglund, J.; Azhar, S.; Lawoko, M.; Lindström, M.; Vilaplana, F.; Wohlert, J.; Henriksson, G. The Structure of Galactoglucomannan Impacts the Degradation under Alkaline Conditions. Cellulose 2019, 26, 2155–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriele, D.; De Cindio, B.; D’Antona, P. A Weak Gel Model for Foods. Rheol. Acta 2001, 40, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil Giraldo, G.A.; Mantovan, J.; Marim, B.M.; Kishima, J.O.F.; Mali, S. Surface Modification of Cellulose from Oat Hull with Citric Acid Using Ultrasonication and Reactive Extrusion Assisted Processes. Polysaccharides 2021, 2, 218–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kačuráková, M.; Wilson, R.H. Developments in Mid-Infrared FT-IR Spectroscopy of Selected Carbohydrates. Carbohydr. Polym. 2001, 44, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.-Y. Thermal Properties and Thermal Degradation of Cellulose Tri-Stearate (CTs). Polymers 2012, 4, 1012–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, M.; Khan, M.; Rehman, T.u.; Ali, I.; Shah, L.A.; Khattak, N.S.; Khan, M.S. Synthesis and Rheological Survey of Xanthan Gum Based Terpolymeric Hydrogels. Z. Für Phys. Chem. 2021, 235, 609–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viscoelastic Properties of Polymers Ferry. Available online: https://drive.google.com/file/d/18n-wM41keS8Yjdn_ipaZ0jWN03uRELd0/view?usp=sharing_eil&ts=6911a0ff&usp=embed_facebook (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Coppola, L.; Gianferri, R.; Nicotera, I.; Oliviero, C.; Ranieri, G.A. Structural Changes in CTAB/H2O Mixtures Using a Rheological Approach. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2004, 6, 2364–2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Corrente, G.A.; Arias Arias, F.E.; Giorno, E.; Caputo, P.; Godbert, N.; Oliviero Rossi, C.; Aiello, I.; Milone, C.; Beneduci, A. Eco-Friendly Hydrogels from Natural Gums and Cellulose Citrate: Formulations and Properties. Gels 2025, 11, 1005. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11121005

Corrente GA, Arias Arias FE, Giorno E, Caputo P, Godbert N, Oliviero Rossi C, Aiello I, Milone C, Beneduci A. Eco-Friendly Hydrogels from Natural Gums and Cellulose Citrate: Formulations and Properties. Gels. 2025; 11(12):1005. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11121005

Chicago/Turabian StyleCorrente, Giuseppina Anna, Fabian Ernesto Arias Arias, Eugenia Giorno, Paolino Caputo, Nicolas Godbert, Cesare Oliviero Rossi, Iolinda Aiello, Candida Milone, and Amerigo Beneduci. 2025. "Eco-Friendly Hydrogels from Natural Gums and Cellulose Citrate: Formulations and Properties" Gels 11, no. 12: 1005. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11121005

APA StyleCorrente, G. A., Arias Arias, F. E., Giorno, E., Caputo, P., Godbert, N., Oliviero Rossi, C., Aiello, I., Milone, C., & Beneduci, A. (2025). Eco-Friendly Hydrogels from Natural Gums and Cellulose Citrate: Formulations and Properties. Gels, 11(12), 1005. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11121005