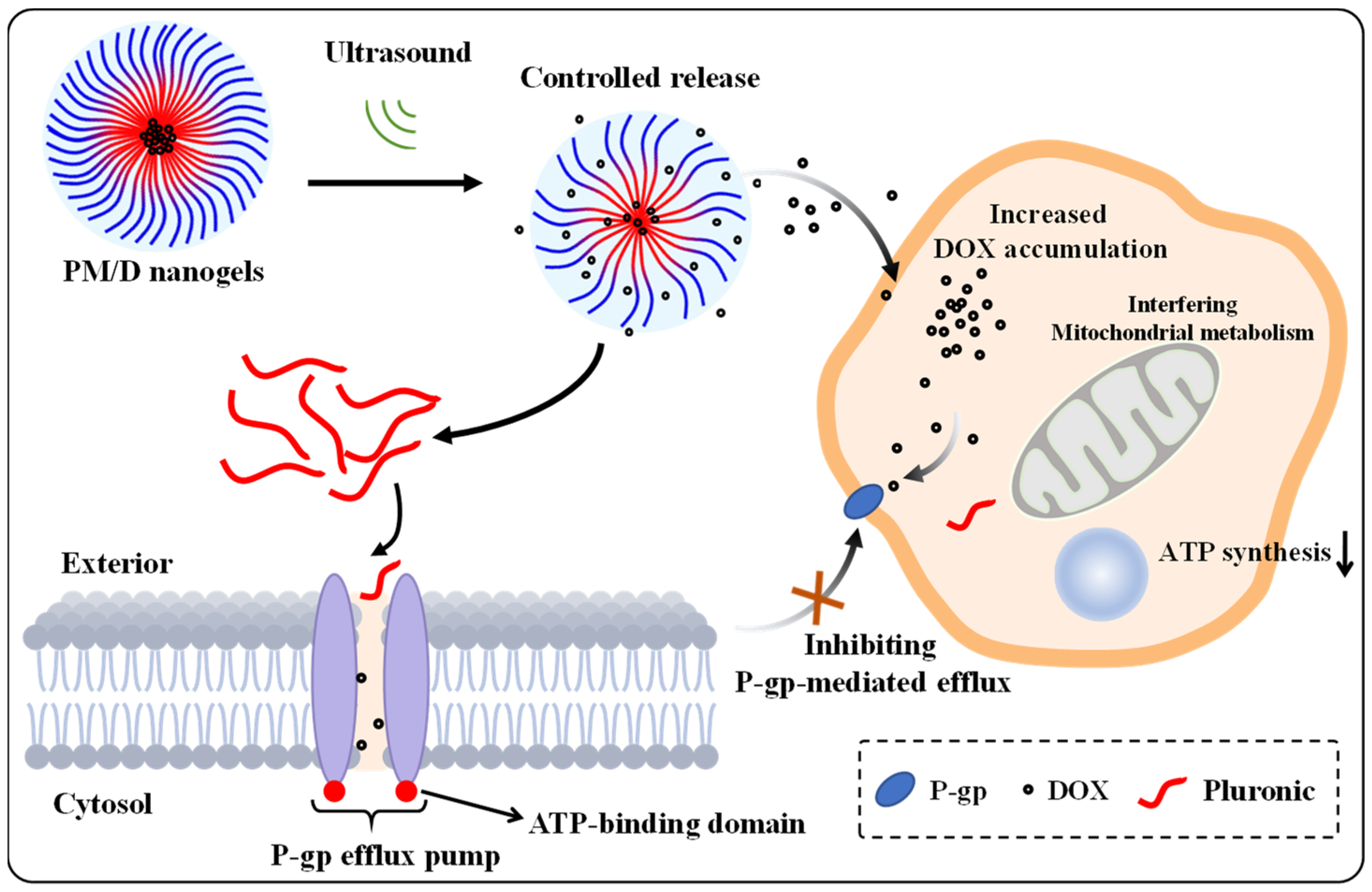

Ultrasonic-Responsive Pluronic P105/F127 Nanogels for Overcoming Multidrug Resistance in Cancer

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Preparation and Characterization of Pluronic Nanogels

4.2.1. The Preparation of PM

4.2.2. The Preparation of PM/D

4.2.3. Measurement of DOX-Encapsulating Efficiency

4.2.4. Determination of the Release Behavior of the Nanogels

4.2.5. In Vitro Biocompatibility

4.3. Cytotoxicity and Cell Uptake Test

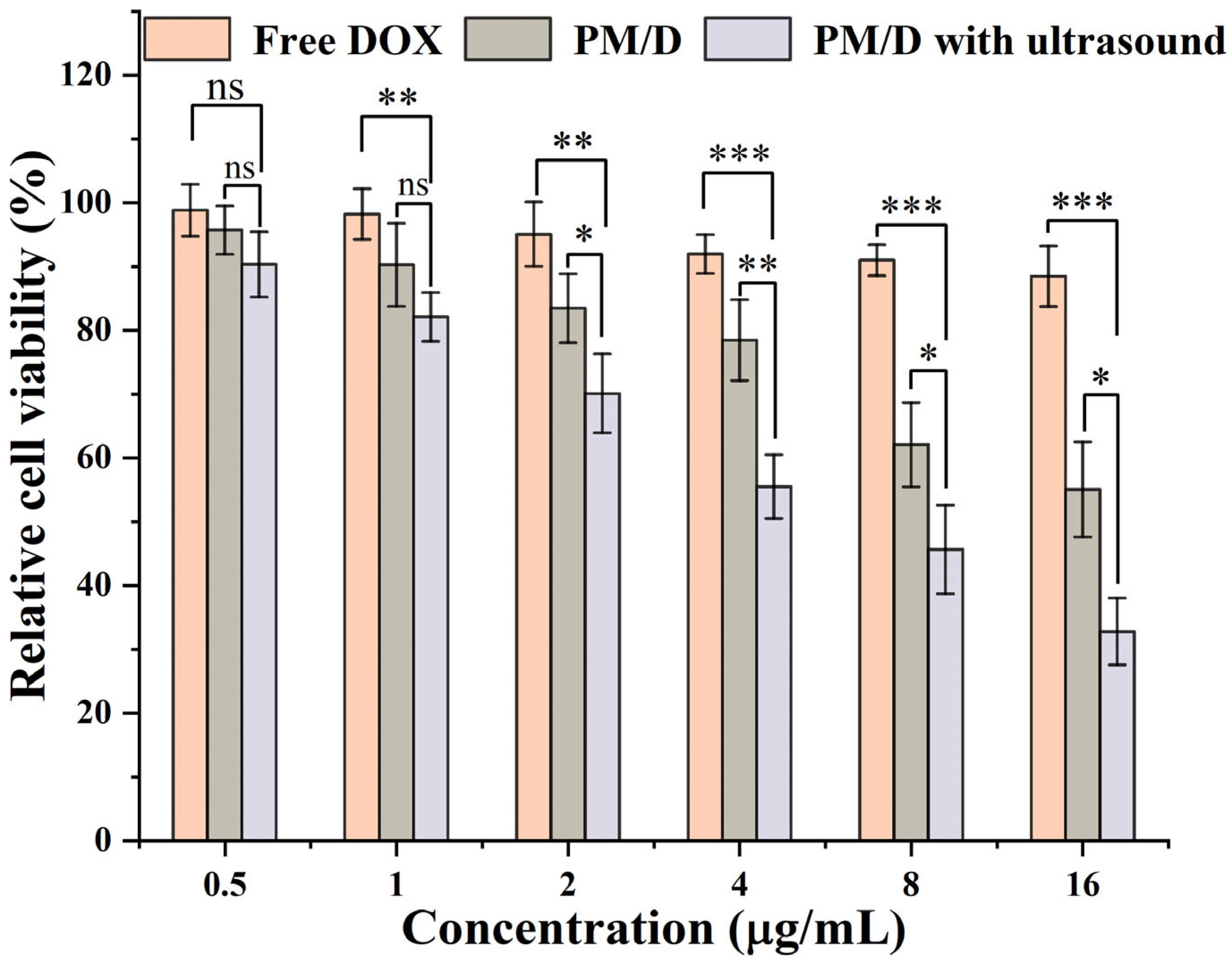

4.3.1. Cell Cytotoxicity

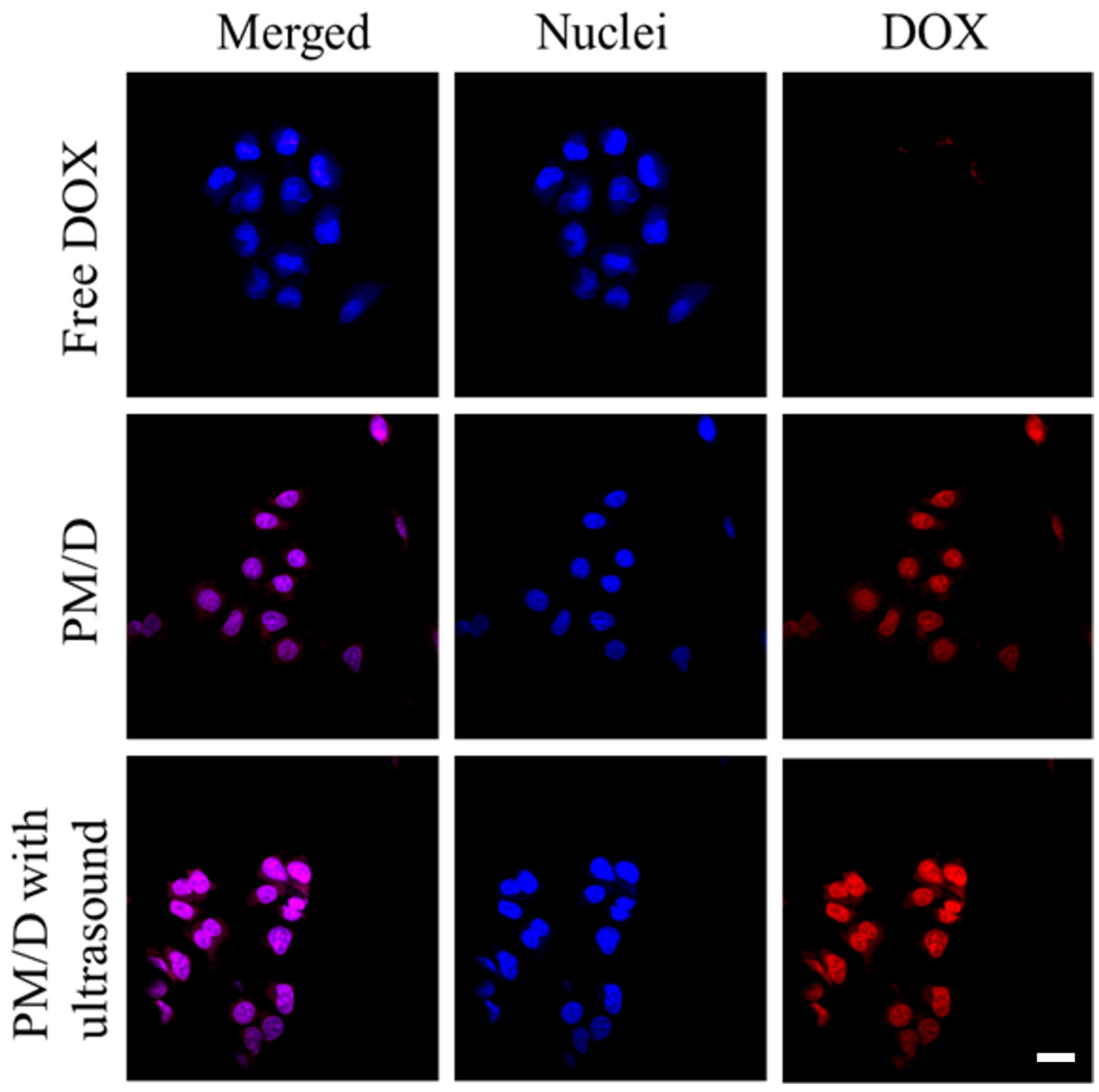

4.3.2. Cell Uptake Test

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Du, J.; Meng, X.; Yang, M.; Chen, G.; Li, J.; Zhu, Z.; Wu, X.; Hu, W.; Tian, M.; Li, T.; et al. NGR-Modified CAF-Derived Exos Targeting Tumor Vasculature to Induce Ferroptosis and Overcome Chemoresistance in Osteosarcoma. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, 2410918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, A.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wu, A.; Wang, Q.; Xia, X.; Chen, X.; Zhao, W.; et al. Zinc Nanoparticles from Oral Supplements Accumulate in Renal Tumours and Stimulate Antitumour Immune Responses. Nat. Mater. 2025, 24, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Wang, C.; Lv, M.; Fan, Z.; Du, J. Mitochondrial-Targeting Nanoprodrugs to Mutually Reinforce Metabolic Inhibition and Autophagy for Combating Resistant Cancer. Biomaterials 2021, 278, 121168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, M.; Wang, C.; Lv, M.; Fan, Z.; Du, J. Intracellular Self-Assembly of Peptides to Induce Apoptosis against Drug-Resistant Melanoma. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 7337–7345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, W.; Zhou, Z.; Li, Z.; Yan, J.; Wang, Y. From Foe to Friend: Rewiring Oncogenic Pathways through Artificial Selenoprotein to Combat Immune-Resistant Tumor. J. Pharm. Anal. 2025, 101322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, G.S.; Gupta, A.K.; Pal, D.; Vaishnav, Y.; Kumar, N.; Annadurai, S.; Jain, S.K. Designing Novel Cabozantinib Analogues as P-Glycoprotein Inhibitors to Target Cancer Cell Resistance Using Molecular Docking Study, ADMET Screening, Bioisosteric Approach, and Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Front. Chem. 2025, 13, 1543075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Lin, Y.; Xiao, H.; Fu, Z.; Zhu, X.; Chen, X.; Li, C.; Ding, C.; Lu, C. mRNA-Responsive Two-in-One Nanodrug for Enhanced Anti-Tumor Chemo-Gene Therapy. J. Control Release 2024, 369, 765–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Y.; Du, H.; Zhang, W.; Yang, D.; Tang, K.; Fang, Q.; Zhang, J. Insights into Tumor Size-Dependent Nanoparticle Accumulation Using Deformed Organosilica Nanoprobes. Mater. Chem. Front. 2024, 8, 3321–3330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, D.; Ma, S.; Sun, T.; Li, Y.; Wei, J.; Wang, C.; Chen, X.; Liao, Y. Pulmonary Delivery of Dual-Targeted Nanoparticles Improves Tumor Accumulation and Cancer Cell Targeting by Restricting Macrophage Interception in Orthotopic Lung Tumors. Biomaterials 2025, 315, 122955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, M.; Han, Y.; Tang, J.; Piao, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhou, Z.; Gao, J.; Rao, J.; Shen, Y. A Tumor-Specific Cascade Amplification Drug Release Nanoparticle for Overcoming Multidrug Resistance in Cancers. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1702342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Nie, C.; Wang, Z.; Lan, F.; Wan, L.; Li, A.; Zheng, P.; Zhu, W.; Pan, Q. A Spatial Confinement Biological Heterogeneous Cascade Nanozyme Composite Hydrogel Combined with Nitric Oxide Gas Therapy for Enhanced Treatment of Psoriasis and Diabetic Wound. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 507, 160629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, I.; Slavkova, M.; Popova, T.; Tzankov, B.; Stefanova, D.; Tzankova, V.; Tzankova, D.; Spassova, I.; Kovacheva, D.; Voycheva, C. Agar Graft Modification with Acrylic and Methacrylic Acid for the Preparation of pH-Sensitive Nanogels for 5-Fluorouracil Delivery. Gels 2024, 10, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Udabe, J.; Muñoz-Juan, A.; Tafech, B.; Orellano, M.S.; Hedtrich, S.; Laromaine, A.; Calderón, M. Modulating the Mucosal Drug Delivery Efficiency of Polymeric Nanogels Tuning Their Redox Response and Surface Charge. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2407044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; You, X.; Wang, L.; Zeng, J.; Huang, H.; Wu, J. ROS-Responsive and Self-Tumor Curing Methionine Polymer Library Based Nanoparticles with Self-Accelerated Drug Release and Hydrophobicity/Hydrophilicity Switching Capability for Enhanced Cancer Therapy. Small 2024, 20, 2401438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Li, S.; Wang, L. Engineered Iron Oxide Nanoplatforms: Reprogramming Immunosuppressive Niches for Precision Cancer Theranostics. Mol. Cancer 2025, 24, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzoni, S.; Rodríguez-Nogales, C.; Blanco-Prieto, M.J. Targeting Tumor Microenvironment with RGD-Functionalized Nanoparticles for Precision Cancer Therapy. Cancer Lett. 2025, 614, 217536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avcı, B.G.; Tornacı, S.; González-Garcinuño, Á.; Tabernero, A.; Çamoğlu, H.; Kaçar, G.; Erken, E.; Toksoy Öner, E. From in Silico Design to in Vitro Validation: Surfactant Free Synthesis of Oleuropein Loaded Levan Nanoparticles. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 366, 123840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacko, R.T.; Ventura, J.; Zhuang, J.; Thayumanavan, S. Polymer Nanogels: A Versatile Nanoscopic Drug Delivery Platform. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2012, 64, 836–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, S.; Ouyang, B.; Xin, Y.; Zhao, W.; Shen, S.; Zhan, M.; Lu, L. Hypoxia-Degradable and Long-Circulating Zwitterionic Phosphorylcholine-Based Nanogel for Enhanced Tumor Drug Delivery. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2021, 11, 560–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Cai, T.; Shao, C.; Xiao, Y.; Xiang, Y.; Jiang, Y. MXene-Based Responsive Hydrogels and Applications in Wound Healing. ChemistrySelect 2024, 9, e202402073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Huang, J.; Wu, J. pH-Sensitive Nanogels for Drug Delivery in Cancer Therapy. Biomater. Sci. 2021, 9, 574–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutradhar, S.C.; Banik, N.; Bari, G.A.K.M.R.; Jeong, J.-H. Polymer Network-Based Nanogels and Microgels: Design, Classification, Synthesis, and Applications in Drug Delivery. Gels 2025, 11, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Zhang, J.; Wu, W.; Banerjee, P.; Zhou, S. Biocompatible Anisole-Nonlinear PEG Core–Shell Nanogels for High Loading Capacity, Excellent Stability, and Controlled Release of Curcumin. Gels 2023, 9, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, J.H.; Hong, S.; Lee, H. Bio-Inspired Adhesive Catechol-Conjugated Chitosan for Biomedical Applications: A Mini Review. Acta Biomater. 2015, 27, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfazani, T.S.; Elsupikhe, R.F.; Abuissa, H.M.; Baiej, K.M. Physical Characterization of Polyethylene Glycol Modified by Solid Lipid Nanoparticles for Targeted Drug Delivery. J. Nano Res. 2024, 85, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alakhova, D.Y.; Kabanov, A.V. Pluronics and MDR Reversal: An Update. Mol. Pharm. 2014, 11, 2566–2578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Qiu, H.; Yin, S.; Wang, H.; Li, Y. Polymeric Drug Delivery System Based on Pluronics for Cancer Treatment. Molecules 2021, 26, 3610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tian, Y.; Jia, X.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, D.; Xie, H.; Zang, D.; Liu, T. Effect of Pharmaceutical Excipients on Micellization of Pluronic and the Application as Drug Carrier to Reverse MDR. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 383, 122182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaliq, N.U.; Lee, J.; Kim, S.; Sung, D.; Kim, H. Pluronic F-68 and F-127 Based Nanomedicines for Advancing Combination Cancer Therapy. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pourbakhsh, M.; Jabraili, M.; Akbari, M.; Jaymand, M.; Jahanban Esfahlan, R. Poloxamer-Based Drug Delivery Systems: Frontiers for Treatment of Solid Tumors. Mater. Today Bio 2025, 32, 101727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, V.; Gaymalov, Z.; Alakhova, D.; Gupta, R.; Zucker, I.H.; Kabanov, A.V. Horizontal Gene Transfer from Macrophages to Ischemic Muscles upon Delivery of Naked DNA with Pluronic Block Copolymers. Biomaterials 2016, 75, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Liu, J.; Yu, X.; Li, J.; Lu, X.; Shen, T. Pluronic F127 and D-α-Tocopheryl Polyethylene Glycol Succinate (TPGS) Mixed Micelles for Targeting Drug Delivery across The Blood Brain Barrier. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 2964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Song, J.; Zhou, P.; Shu, Y.; Liang, P.; Liang, H.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, X.; Shan, X.; Wu, X. An Ultrasound-Triggered Injectable Sodium Alginate Scaffold Loaded with Electrospun Microspheres for on-Demand Drug Delivery to Accelerate Bone Defect Regeneration. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 334, 122039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, D.; Wang, J.; Song, C.; Zhao, Y. Ultrasound-Responsive Matters for Biomedical Applications. Innovation 2023, 4, 100421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, X.; Yi, W.; Chen, S.; Cai, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Han, W.; Guo, X.; Shen, J.; Cui, W.; Bai, D. Ultrasound-Responsive Smart Composite Biomaterials in Tissue Repair. Nano Today 2023, 49, 101804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, H.; Huang, J.; Gui, B.; Chen, Y.; Guo, Y.; Lian, Y.; Pan, J.; Hu, Y.; Jiang, N.; Deng, Q.; et al. Ultrasound-Responsive Nanobubbles for Breast Cancer: Synergistic Sonodynamic, Chemotherapy, and Immune Activation through the cGAS-STING Pathway. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 19317–19334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Fain, H.D.; Rapoport, N. Ultrasound-Enhanced Tumor Targeting of Polymeric Micellar Drug Carriers. Mol. Pharm. 2004, 1, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tian, T.; Zeng, Z.; Chen, C.; Wang, R.; Chen, S.; Zheng, H. ROS-Responsive Conjugated Polymer Nanoparticles Triggered by Ultrasound for Camptothecin Release in Breast Cancer Combination Therapy. J. Mater. Chem. B 2025, 13, 8446–8460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeingst, T.J.; Arrizabalaga, J.H.; Hayes, D.J. Ultrasound-Induced Drug Release from Stimuli-Responsive Hydrogels. Gels 2022, 8, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awad, N.S.; Paul, V.; AlSawaftah, N.M.; Ter Haar, G.; Allen, T.M.; Pitt, W.G.; Husseini, G.A. Ultrasound-Responsive Nanocarriers in Cancer Treatment: A Review. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2021, 4, 589–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanassiadis, A.G.; Ma, Z.; Moreno-Gomez, N.; Melde, K.; Choi, E.; Goyal, R.; Fischer, P. Ultrasound-Responsive Systems as Components for Smart Materials. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 5165–5208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Formulation | IC 50 (μg/mL) | RRI a |

|---|---|---|

| Free DOX | 37.89 | - |

| PM/D | 16.54 | 2.29 |

| PM/D with ultrasound | 8.32 | 4.55 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, S.; Sun, M.; Fan, Z. Ultrasonic-Responsive Pluronic P105/F127 Nanogels for Overcoming Multidrug Resistance in Cancer. Gels 2025, 11, 878. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11110878

Liu S, Sun M, Fan Z. Ultrasonic-Responsive Pluronic P105/F127 Nanogels for Overcoming Multidrug Resistance in Cancer. Gels. 2025; 11(11):878. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11110878

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Shangpeng, Min Sun, and Zhen Fan. 2025. "Ultrasonic-Responsive Pluronic P105/F127 Nanogels for Overcoming Multidrug Resistance in Cancer" Gels 11, no. 11: 878. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11110878

APA StyleLiu, S., Sun, M., & Fan, Z. (2025). Ultrasonic-Responsive Pluronic P105/F127 Nanogels for Overcoming Multidrug Resistance in Cancer. Gels, 11(11), 878. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11110878