Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis Situation among Post Tuberculosis Patients in Vietnam: An Observational Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

2.2. Clinical Samples and Radiological Findings

2.3. Serology Test

2.4. Treatment

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.6. Ethical Issues

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2019; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; ISBN 978-92-4-156571-4. [Google Scholar]

- Denning, D.W.; Cadranel, J.; Beigelman-Aubry, C.; Ader, F.; Chakrabarti, A.; Blot, S.; Ullmann, A.J.; Dimopoulos, G.; Lange, C. European Society for Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases and European Respiratory Society Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis: Rationale and clinical guidelines for diagnosis and management. Eur. Respir. J. 2016, 47, 45–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozaliyani, A.; Rosianawati, H.; Handayani, D.; Agustin, H.; Zaini, J.; Syam, R.; Adawiyah, R.; Tugiran, M.; Setianingrum, F.; Burhan, E.; et al. Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis in Post Tuberculosis Patients in Indonesia and the Role of LDBio Aspergillus ICT as Part of the Diagnosis Scheme. J. Fungi 2020, 6, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harries, A.D.; Dlodlo, R.A.; Brigden, G.; Mortimer, K.; Jensen, P.; Fujiwara, P.I.; Castro, J.L.; Chakaya, J.M. Should we consider a “fourth 90” for tuberculosis? Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2019, 23, 1253–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beardsley, J.; Denning, D.W.; Chau, N.V.; Yen, N.T.B.; Crump, J.A.; Day, J.N. Estimating the burden of fungal disease in Vietnam. Mycoses 2015, 58 (Suppl. 5), 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bongomin, F.; Kwizera, R.; Atukunda, A.; Kirenga, B.J. Cor pulmonale complicating chronic pulmonary aspergillosis with fatal consequences: Experience from Uganda. Med. Mycol. Case Rep. 2019, 25, 22–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (PDF) Unprecedented Prevalence of Azole-Resistant Aspergillus Fumigatus Identified in the Environment of Vietnam, with Marked Variability by Land Use Type. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/346424769_Unprecedented_Prevalence_of_Azole-Resistant_Aspergillus_fumigatus_Identified_in_the_Environment_of_Vietnam_with_Marked_Variability_by_Land_Use_Type (accessed on 11 March 2021).

- Diagnosis and Management of Aspergillus Diseases: Executive Summary of the 2017 ESCMID-ECMM-ERS Guideline—Clinical Microbiology and Infection. Available online: https://www.clinicalmicrobiologyandinfection.com/article/S1198-743X(18)30051-X/fulltext (accessed on 11 March 2021).

- Denning, D.W.; Page, I.D.; Chakaya, J.; Jabeen, K.; Jude, C.M.; Cornet, M.; Alastruey-Izquierdo, A.; Bongomin, F.; Bowyer, P.; Chakrabarti, A.; et al. Case Definition of Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis in Resource-Constrained Settings. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2018, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladele, R.; Otu, A.A.; Olubamwo, O.; Makanjuola, O.B.; Ochang, E.A.; Ejembi, J.; Irurhe, N.; Ajanaku, I.; Ekundayo, H.A.; Olayinka, A.; et al. Evaluation of knowledge and awareness of invasive fungal infections amongst resident doctors in Nigeria. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2020, 36, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, H.N.; Sriplung, H.; Chongsuvivatwong, V.; Nguyen, N.V.; Nguyen, T.H. The accuracy of tuberculous meningitis diagnostic tests using Bayesian latent class analysis. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2020, 14, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beltrán Rodríguez, N.; San Juan-Galán, J.L.; Fernández Andreu, C.M.; María Yera, D.; Barrios Pita, M.; Perurena Lancha, M.R.; Velar Martínez, R.E.; Illnait Zaragozí, M.T.; Martínez Machín, G.F. Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis in Patients with Underlying Respiratory Disorders in Cuba-A Pilot Study. J. Fungi 2019, 5, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thwaites, G.; Caws, M.; Chau, T.T.H.; D’Sa, A.; Lan, N.T.N.; Huyen, M.N.T.; Gagneux, S.; Anh, P.T.H.; Tho, D.Q.; Torok, E.; et al. Relationship between Mycobacterium tuberculosis genotype and the clinical phenotype of pulmonary and meningeal tuberculosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2008, 46, 1363–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thorson, A.; Long, N.H.; Larsson, L.O. Chest X-ray findings in relation to gender and symptoms: A study of patients with smear positive tuberculosis in Vietnam. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 2007, 39, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanh, N.P.; Khue, P.M.; Sy, D.N.; Strobel, M. Diabetes among new cases of pulmonary tuberculosis in Hanoï, Vietnam. Bull. Soc. Pathol. Exot. 1990 2015, 108, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setianingrum, F.; Rozaliyani, A.; Syam, R.; Adawiyah, R.; Tugiran, M.; Sari, C.Y.I.; Burhan, E.; Wahyuningsih, R.; Rautemaa-Richardson, R.; Denning, D.W. Evaluation and comparison of automated and manual ELISA for diagnosis of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis (CPA) in Indonesia. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2020, 98, 115124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.-R.; Huang, H.-L.; Chen, L.-C.; Yang, H.-C.; Ko, J.-C.; Cheng, M.-H.; Chong, I.-W.; Lee, L.-N.; Wang, J.-Y.; Dimopoulos, G. Seroprevalence of Aspergillus IgG and disease prevalence of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis in a country with intermediate burden of tuberculosis: A prospective observational study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Off. Publ. Eur. Soc. 2020, 26, e1–e1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Iqbal, N.; Irfan, M.; Zubairi, A.B.S.; Jabeen, K.; Awan, S.; Khan, J.A. Clinical manifestations and outcomes of pulmonary aspergillosis: Experience from Pakistan. BMJ Open Respir. Res. 2016, 3, e000155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Denning, D.W.; Riniotis, K.; Dobrashian, R.; Sambatakou, H. Chronic Cavitary and Fibrosing Pulmonary and Pleural Aspergillosis: Case Series, Proposed Nomenclature Change, and Review. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2003, 37, S265–S280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Baker, M.A.; Harries, A.D.; Jeon, C.Y.; Hart, J.E.; Kapur, A.; Lönnroth, K.; Ottmani, S.-E.; Goonesekera, S.D.; Murray, M.B. The impact of diabetes on tuberculosis treatment outcomes: A systematic review. BMC Med. 2011, 9, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Iqbal, N.; Irfan, M.; Jabeen, K.; Kazmi, M.M.; Tariq, M.U. Chronic pulmonary mucormycosis: An emerging fungal infection in diabetes mellitus. J. Thorac. Dis. 2017, 9, E121–E125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hayes, G.E.; Novak-Frazer, L. Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis-Where Are We? and Where Are We Going? J. Fungi 2016, 2, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ngo, C.Q.; Phan, D.M.; Vu, G.V.; Dao, P.N.; Phan, P.T.; Chu, H.T.; Nguyen, L.H.; Vu, G.T.; Ha, G.H.; Tran, T.H.; et al. Inhaler Technique and Adherence to Inhaled Medications among Patients with Acute Exacerbation of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease in Vietnam. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2019, 16, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hedayati, M.T.; Azimi, Y.; Droudinia, A.; Mousavi, B.; Khalilian, A.; Hedayati, N.; Denning, D.W. Prevalence of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis in patients with tuberculosis from Iran. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Eur. Soc. Clin. Microbiol. 2015, 34, 1759–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denning, D.W.; Pleuvry, A.; Cole, D.C. Global burden of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis as a sequel to pulmonary tuberculosis. Bull. World Health Organ. 2011, 89, 864–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tashiro, T.; Izumikawa, K.; Tashiro, M.; Morinaga, Y.; Nakamura, S.; Imamura, Y.; Miyazaki, T.; Kakeya, H.; Yamamoto, Y.; Yanagihara, K.; et al. A Case Series of Chronic Necrotizing Pulmonary Aspergillosis and a New Proposal. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 2013, 66, 312–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schweer, K.E.; Bangard, C.; Hekmat, K.; Cornely, O.A. Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis. Mycoses 2014, 57, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takazono, T.; Izumikawa, K. Recent Advances in Diagnosing Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jewkes, J.; Kay, P.H.; Paneth, M.; Citron, K.M. Pulmonary aspergilloma: Analysis of prognosis in relation to haemoptysis and survey of treatment. Thorax 1983, 38, 572–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Prasad, A.; Agarwal, K.; Deepak, D.; Atwal, S.S. Pulmonary Aspergillosis: What CT can Offer Before it is too Late! J. Clin. Diagn. Res. JCDR 2016, 10, TE01–TE05. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gotway, M.B.; Dawn, S.K.; Caoili, E.M.; Reddy, G.P.; Araoz, P.A.; Webb, W.R. The radiologic spectrum of pulmonary Aspergillus infections. J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 2002, 26, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godet, C.; Laurent, F.; Bergeron, A.; Ingrand, P.; Beigelman-Aubry, C.; Camara, B.; Cottin, V.; Germaud, P.; Philippe, B.; Pison, C.; et al. CT Imaging Assessment of Response to Treatment in Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis. Chest 2016, 150, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghrabi, F.; Denning, D.W. The Management of Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis: The UK National Aspergillosis Centre Approach. Curr. Fungal Infect. Rep. 2017, 11, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Clinical Features and Diagnosis of Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis in Chinese Patients. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5662405/ (accessed on 9 March 2021).

- Raveendran, S.; Lu, Z. CT findings and differential diagnosis in adults with invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. Radiol. Infect. Dis. 2018, 5, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, I.D.; Byanyima, R.; Hosmane, S.; Onyachi, N.; Opira, C.; Richardson, M.; Sawyer, R.; Sharman, A.; Denning, D.W. Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis commonly complicates treated pulmonary tuberculosis with residual cavitation. Eur. Respir. J. 2019, 53, 1801184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, I.D.; Richardson, M.D.; Denning, D.W. Comparison of six Aspergillus-specific IgG assays for the diagnosis of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis (CPA). J. Infect. 2016, 72, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Rui, Y.; Zhou, W.; Liu, L.; He, B.; Shi, Y.; Su, X. Role of the Aspergillus-Specific IgG and IgM Test in the Diagnosis and Follow-Up of Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, M.D.; Page, I.D. Aspergillus serology: Have we arrived yet? Med. Mycol. 2017, 55, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alastruey-Izquierdo, A.; Cadranel, J.; Flick, H.; Godet, C.; Hennequin, C.; Hoenigl, M.; Kosmidis, C.; Lange, C.; Munteanu, O.; Page, I.; et al. Treatment of Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis: Current Standards and Future Perspectives. Respir. Int. Rev. Thorac. Dis. 2018, 96, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Features | No. | Statistics |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline demographics | ||

| CPA confirmed cases | 40 | |

| Age mean (SD)/Median (IQR) | 59 | 2.3 (54.4–63.6) |

| Males | 28 | 73.7% |

| Females | 10 | 26.3% |

| BMI | 19.0 | 0.49 (18.0–20.0) |

| Comorbidities | ||

| Diabetes | 5 | 12.5% |

| COPD | 8 | 20% |

| Bronchiectasis | 3 | 7.5% |

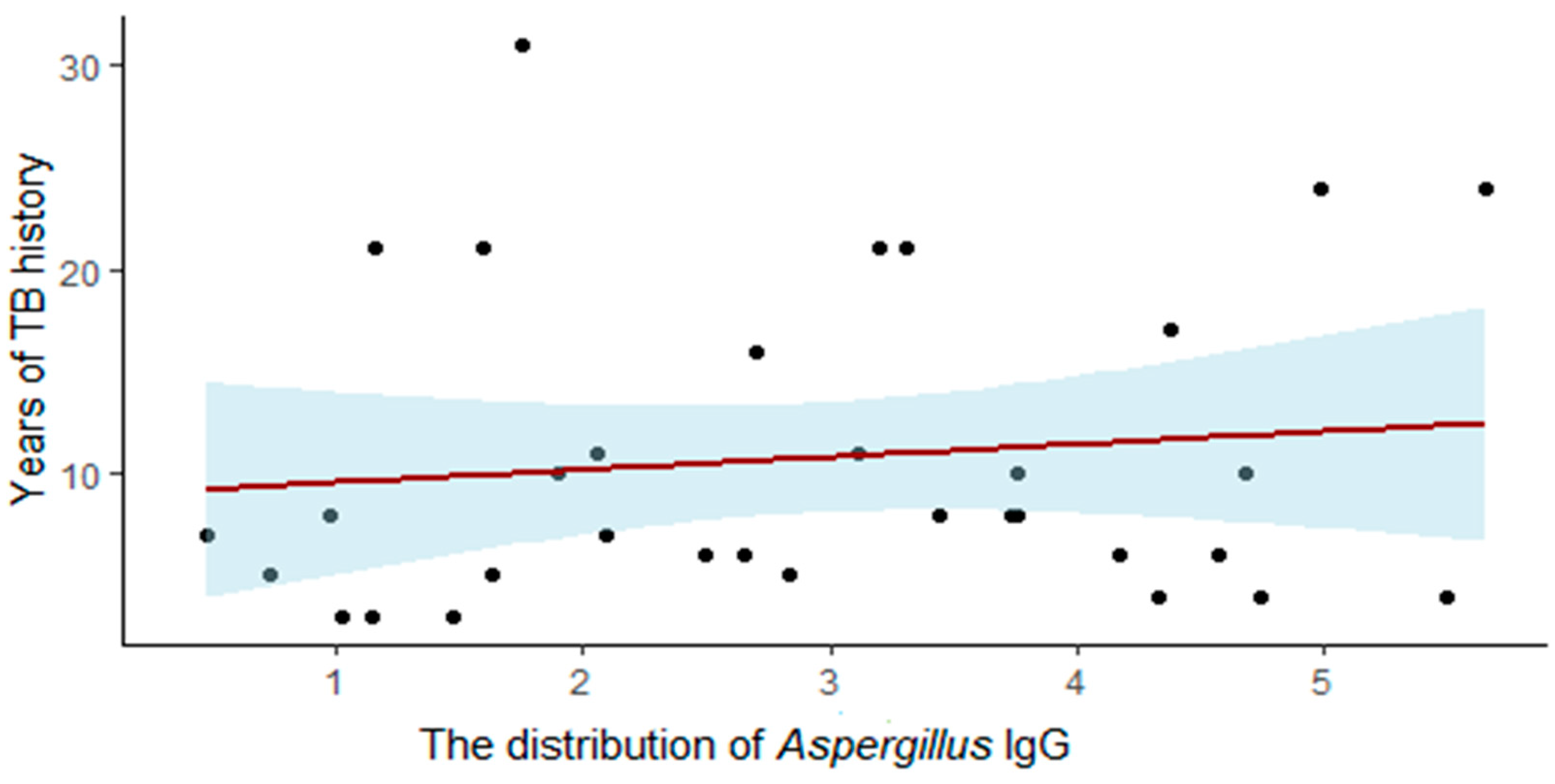

| Interval after TB to CPA presentation | ||

| <5 years | 9 | 27.3% |

| 5–10 years | 10 | 30.3% |

| >10 years | 14 | 42.4% |

| Clinical symptoms | ||

| Cough | 37 | 97.4% |

| Productive cough | 31 | 81.6% |

| Hemoptysis | 18 | 47.4% |

| Dyspnea | 21 | 55.3% |

| Fever | 8 | 21.1% |

| Weight loss | 14 | 36.8% |

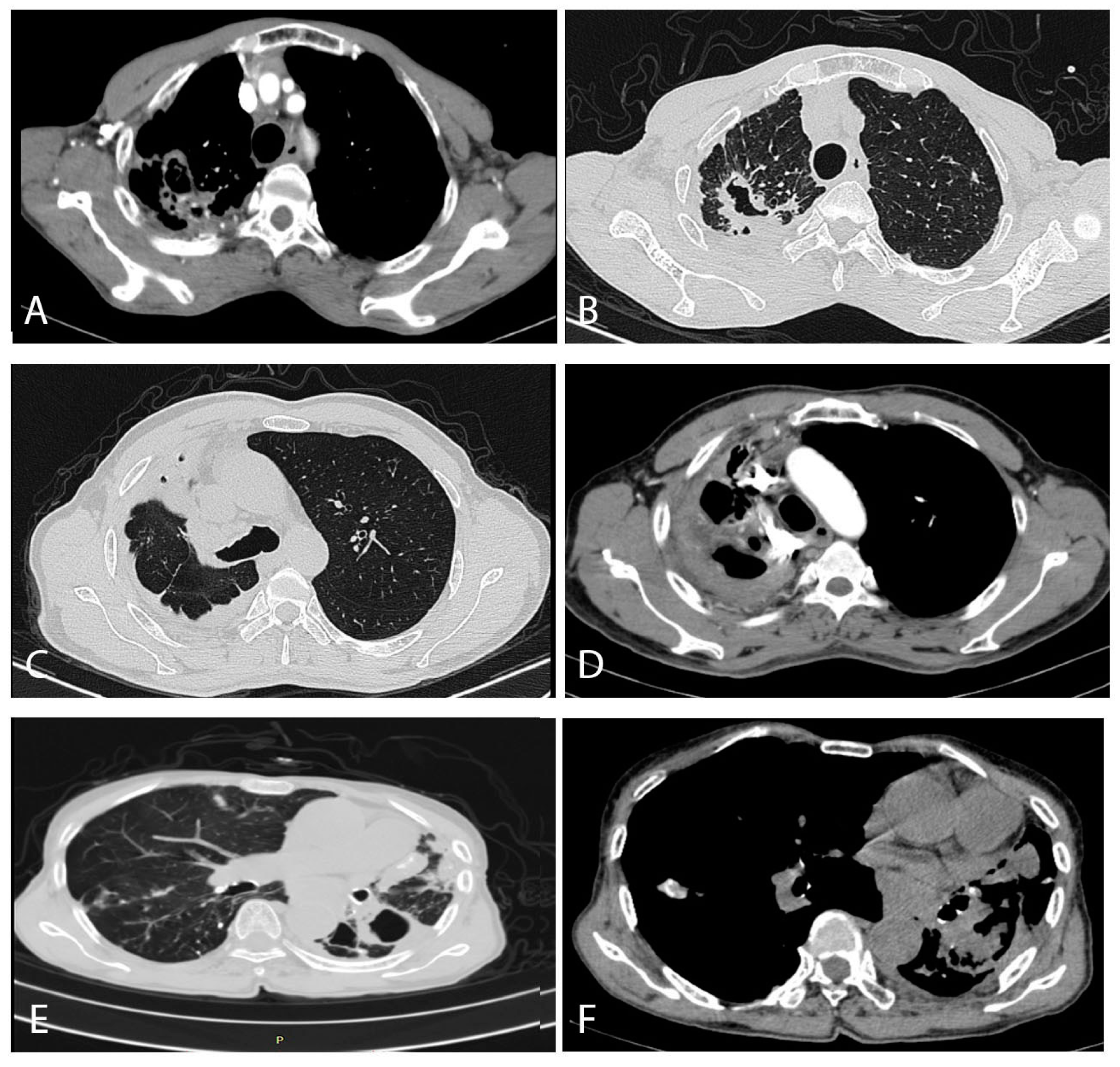

| Chest X-ray radiological findings | ||

| Cavitary lesion | 8 | 21.1% |

| Aspergilloma | 5 | 13.2% |

| Pleural thickening | 30 | 79.0% |

| Hemithorax | 5 | 21.1% |

| Chest CT findings | ||

| Bilateral | 19 | 50.0% |

| Left | 7 | 18.4% |

| Right | 12 | 31.6% |

| Multiple cavities with thickened pleura | 20 | 52.6% |

| Fungal ball(s) (aspergilloma) | 11 | 28.9% |

| Single cavity with thickened pleura | 6 | 15.8% |

| Pleural thickening | 17 | 44.7% |

| Bronchiectasis | 10 | 26.3% |

| Non-specific infiltrates | 11 | 28.9% |

| Blood Test | Mean/Median | SD/IQR | Normal Range |

| WBC | 10.6 | 4.9 | 4.5–11. 0 |

| CRP | 60.9 | 71.7 | 0–5.0 |

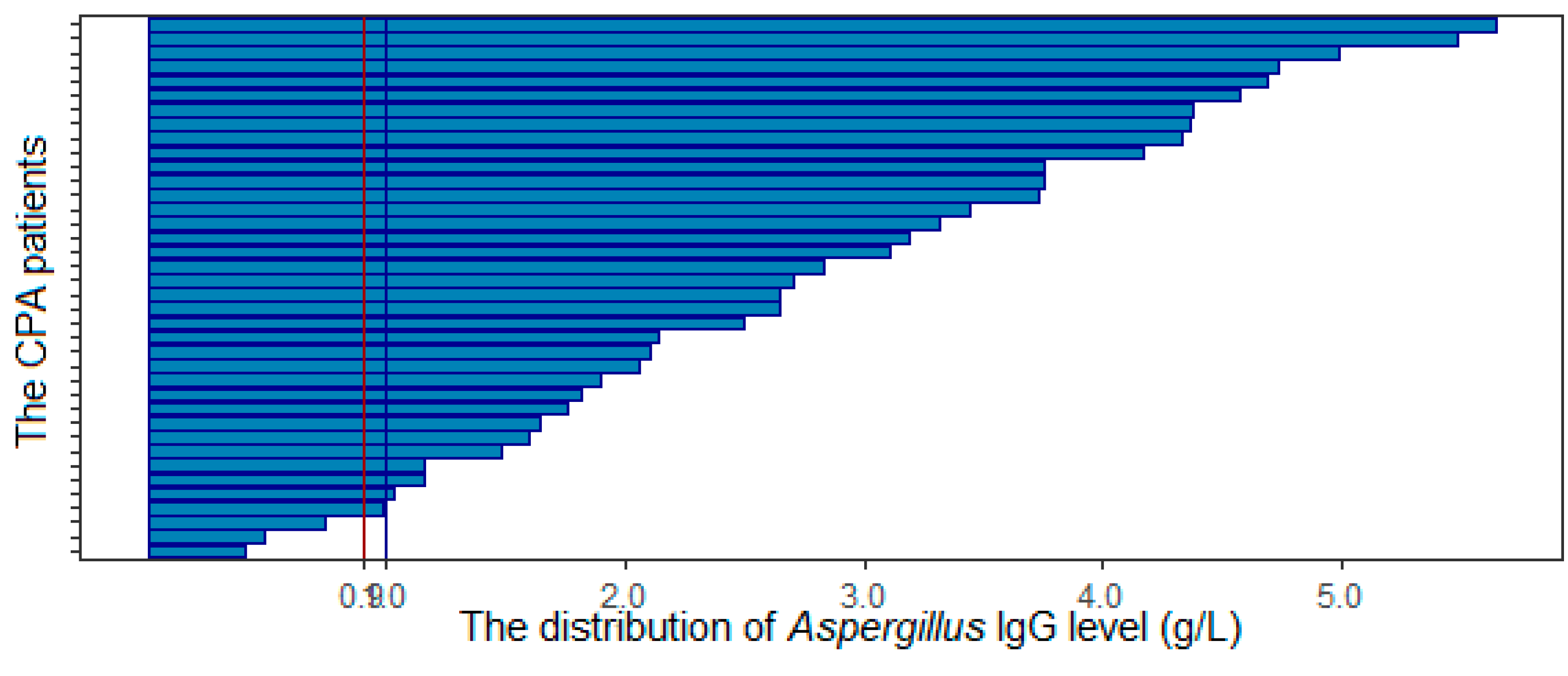

| Aspergillus IgG | 2.82 | 1.9 | <0.9 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nguyen, N.T.B.; Le Ngoc, H.; Nguyen, N.V.; Dinh, L.V.; Nguyen, H.V.; Nguyen, H.T.; Denning, D.W. Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis Situation among Post Tuberculosis Patients in Vietnam: An Observational Study. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 532. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof7070532

Nguyen NTB, Le Ngoc H, Nguyen NV, Dinh LV, Nguyen HV, Nguyen HT, Denning DW. Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis Situation among Post Tuberculosis Patients in Vietnam: An Observational Study. Journal of Fungi. 2021; 7(7):532. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof7070532

Chicago/Turabian StyleNguyen, Ngoc Thi Bich, Huy Le Ngoc, Nhung Viet Nguyen, Luong Van Dinh, Hung Van Nguyen, Huyen Thi Nguyen, and David W. Denning. 2021. "Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis Situation among Post Tuberculosis Patients in Vietnam: An Observational Study" Journal of Fungi 7, no. 7: 532. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof7070532