Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii Species Complexes in Latin America: A Map of Molecular Types, Genotypic Diversity, and Antifungal Susceptibility as Reported by the Latin American Cryptococcal Study Group

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

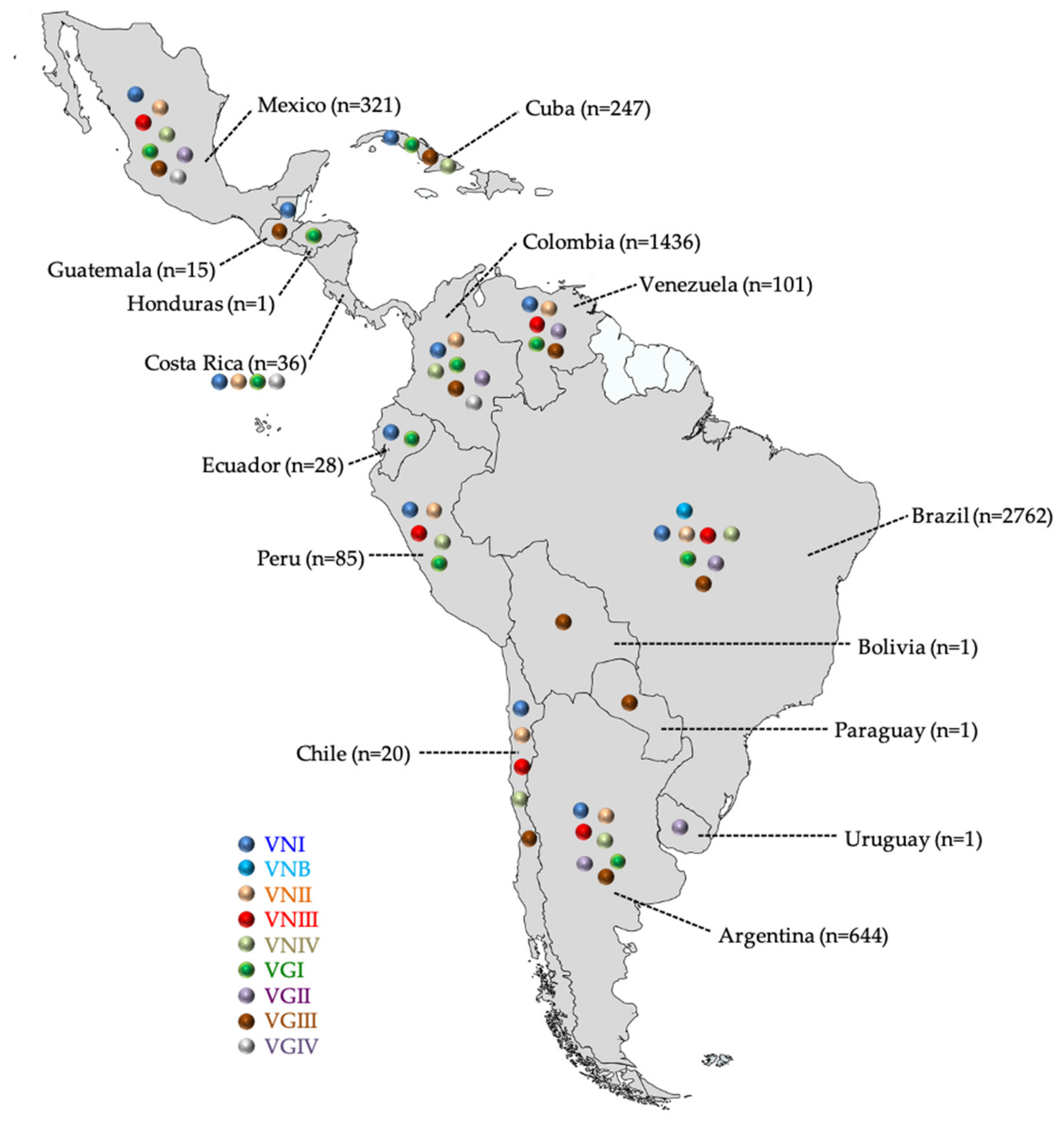

3.1. C. neoformans VNI and C. gattii VGII Predominate in Latin America

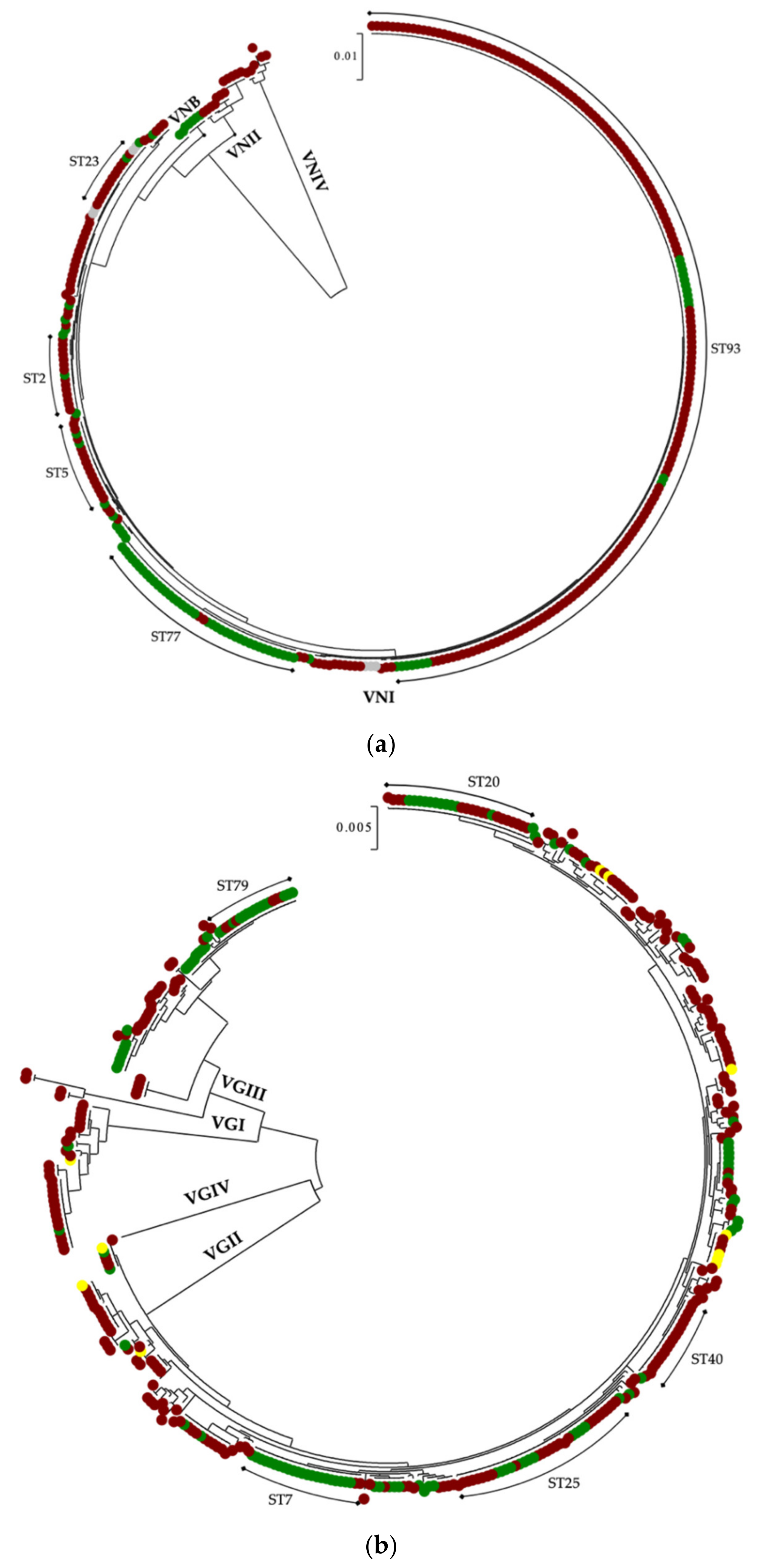

3.2. In Latin America, C. neoformans Species Complex Is Genetically Less Diverse than C. gattii Species Complex

3.3. Most Isolates of C. neoformans and C. gattii Species Complexes from Latin America Show a Wild-Type Antifungal Susceptibility; However, Non-Wild-Type VNI, VGI, VGII, and VGIII Isolates Have Also Been Identified

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Firacative, C.; Lizarazo, J.; Illnait-Zaragozi, M.T.; Castaneda, E. The status of cryptococcosis in Latin America. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2018, 113, e170554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, P.R.; Jarvis, J.N.; Panackal, A.A.; Fisher, M.C.; Molloy, S.F.; Loyse, A.; Harrison, T.S. Cryptococcal meningitis: Epidemiology, immunology, diagnosis and therapy. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2017, 13, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourad, A.; Perfect, J.R. The war on cryptococcosis: A Review of the antifungal arsenal. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2018, 113, e170391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNAIDS. Available online: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/UNAIDS_FactSheet_en.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2021).

- Leimann, B.C.; Koifman, R.J. Cryptococcal meningitis in Rio de Janeiro State, Brazil, 1994-2004. Cad. Saude Publica 2008, 24, 2582–2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escandon, P.; Lizarazo, J.; Agudelo, C.I.; Castaneda, E. Cryptococcosis in Colombia: Compilation and Analysis of Data from Laboratory-Based Surveillance. J. Fungi 2018, 4, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barriga, G.; Asumir, C.; Mercado, N.F. Actualidades y tendencias en la etiología de las meningoencefalitis causadas por hongos y bacterias (1980-2004). Rev. Lat. Patol. Clin. 2005, 52, 240–245. [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Jiménez, M.A.; Rey-Benito, J.R.; Duque-Beltrán, S.; Pinilla-Guevara, C.A.; Bello-Pieruccini, S.; Agudelo-Mahecha, C.M.; Álvarez-Moreno, C.A. Diagnóstico de micosis oportunistas en pacientes con VIH/sida: Un estudio de casos en Colombia. Infectio 2011, 15, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Davel, G.; Canteros, C.E. Epidemiological status of mycoses in the Argentine Republic. Rev. Argent. Microbiol. 2007, 39, 28–33. [Google Scholar]

- Gaona-Flores, V.A.; Campos-Navarro, L.A.; Cervantes-Tovar, R.M.; Alcalá-Martínez, E. The epidemiology of fungemia in an infectious diseases hospital in Mexico city: A 10-year retrospective review. Med. Mycol. 2016, 54, 600–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez-Tovar, L.J.; Mejia-Mercado, J.A.; Manzano-Gayosso, P.; Hernandez-Hernandez, F.; Lopez-Martinez, R.; Silva-Gonzalez, I. Frequency of invasive fungal infections in a Mexican High-Specialty Hospital. Experience of 21 years. Rev. Médica del Inst. Mex. del Seguro Soc. 2016, 54, 581–587. [Google Scholar]

- Reviákina, V.; Panizo, M.; Dolande, M.; Selgrad, S. Diagnóstico inmunológico de las micosis sistémicas durante cinco años 2002–2006. Rev. Soc. Ven Microbiol. 2007, 27, 112–119. [Google Scholar]

- Moreira Tde, A.; Ferreira, M.S.; Ribas, R.M.; Borges, A.S. Cryptococosis: Clinical epidemiological laboratorial study and fungi varieties in 96 patients. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2006, 39, 255–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Meyer, W.; Mitchell, T.G. Polymerase chain reaction fingerprinting in fungi using single primers specific to minisatellites and simple repetitive DNA sequences: Strain variation in Cryptococcus neoformans. Electrophoresis 1995, 16, 1648–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boekhout, T.; Theelen, B.; Diaz, M.; Fell, J.W.; Hop, W.C.; Abeln, E.C.; Dromer, F.; Meyer, W. Hybrid genotypes in the pathogenic yeast Cryptococcus neoformans. Microbiology 2001, 147, 891–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagen, F.; Illnait-Zaragozi, M.T.; Bartlett, K.H.; Swinne, D.; Geertsen, E.; Klaassen, C.H.; Boekhout, T.; Meis, J.F. In vitro antifungal susceptibilities and amplified fragment length polymorphism genotyping of a worldwide collection of 350 clinical, veterinary, and environmental Cryptococcus gattii isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 5139–5145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Illnait-Zaragozi, M.T.; Martinez-Machin, G.F.; Fernandez-Andreu, C.M.; Hagen, F.; Boekhout, T.; Klaassen, C.H.; Meis, J.F. Microsatellite typing and susceptibilities of serial Cryptococcus neoformans isolates from Cuban patients with recurrent cryptococcal meningitis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2010, 10, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, W.; Castañeda, A.; Jackson, S.; Huynh, M.; Castañeda, E. The IberoAmerican Cryptococcal Study Group Molecular typing of IberoAmerican Cryptococcus neoformans isolates. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2003, 9, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, W.; Aanensen, D.M.; Boekhout, T.; Cogliati, M.; Diaz, M.R.; Esposto, M.C.; Fisher, M.; Gilgado, F.; Hagen, F.; Kaocharoen, S.; et al. Consensus multi-locus sequence typing scheme for Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii. Med. Mycol. 2009, 47, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litvintseva, A.P.; Thakur, R.; Vilgalys, R.; Mitchell, T.G. Multilocus sequence typing reveals three genetic subpopulations of Cryptococcus neoformans var. grubii (serotype A), including a unique population in Botswana. Genetics 2006, 172, 2223–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrer, R.A.; Chang, M.; Davis, M.J.; van Dorp, L.; Yang, D.H.; Shea, T.; Sewell, T.R.; Meyer, W.; Balloux, F.; Edwards, H.M.; et al. A new lineage of Cryptococcus gattii (VGV) discovered in the Central Zambezian Miombo Woodlands. MBio 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loftus, B.J.; Fung, E.; Roncaglia, P.; Rowley, D.; Amedeo, P.; Bruno, D.; Vamathevan, J.; Miranda, M.; Anderson, I.J.; Fraser, J.A.; et al. The genome of the basidiomycetous yeast and human pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. Science 2005, 307, 1321–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Souza, C.A.; Kronstad, J.W.; Taylor, G.; Warren, R.; Yuen, M.; Hu, G.; Jung, W.H.; Sham, A.; Kidd, S.E.; Tangen, K.; et al. Genome variation in Cryptococcus gattii, an emerging pathogen of immunocompetent hosts. MBio 2011, 2, e00342-10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagen, F.; Khayhan, K.; Theelen, B.; Kolecka, A.; Polacheck, I.; Sionov, E.; Falk, R.; Parnmen, S.; Lumbsch, H.T.; Boekhout, T. Recognition of seven species in the Cryptococcus gattii/Cryptococcus neoformans species complex. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2015, 78, 16–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon-Chung, K.J.; Bennett, J.E.; Wickes, B.L.; Meyer, W.; Cuomo, C.A.; Wollenburg, K.R.; Bicanic, T.A.; Castaneda, E.; Chang, Y.C.; Chen, J.; et al. The case for adopting the "Species complex" nomenclature for the etiologic agents of cryptococcosis. mSphere 2017, 2, e00357-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon-Chung, K.J.; Fraser, J.A.; Doering, T.L.; Wang, Z.; Janbon, G.; Idnurm, A.; Bahn, Y.S. Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii, the etiologic agents of cryptococcosis. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2014, 4, a019760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinel-Ingroff, A.; Aller, A.I.; Canton, E.; Castanon-Olivares, L.R.; Chowdhary, A.; Cordoba, S.; Cuenca-Estrella, M.; Fothergill, A.; Fuller, J.; Govender, N.; et al. Cryptococcus neoformans-Cryptococcus gattii species complex: An international study of wild-type susceptibility endpoint distributions and epidemiological cutoff values for fluconazole, itraconazole, posaconazole, and voriconazole. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 5898–5906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinel-Ingroff, A.; Chowdhary, A.; Cuenca-Estrella, M.; Fothergill, A.; Fuller, J.; Hagen, F.; Govender, N.; Guarro, J.; Johnson, E.; Lass-Florl, C.; et al. Cryptococcus neoformans-Cryptococcus gattii species complex: An international study of wild-type susceptibility endpoint distributions and epidemiological cutoff values for amphotericin B and flucytosine. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 3107–3113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiesner, D.L.; Moskalenko, O.; Corcoran, J.M.; McDonald, T.; Rolfes, M.A.; Meya, D.B.; Kajumbula, H.; Kambugu, A.; Bohjanen, P.R.; Knight, J.F.; et al. Cryptococcal genotype influences immunologic response and human clinical outcome after meningitis. MBio 2012, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cogliati, M. Global molecular epidemiology of Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii: An atlas of the molecular types. Scientifica 2013, 2013, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Tamura, K. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 7.0 for Bigger Datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016, 33, 1870–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firacative, C.; Roe, C.C.; Malik, R.; Ferreira-Paim, K.; Escandon, P.; Sykes, J.E.; Castanon-Olivares, L.R.; Contreras-Peres, C.; Samayoa, B.; Sorrell, T.C.; et al. MLST and whole-genome-based population analysis of Cryptococcus gattii VGIII links clinical, veterinary and environmental strains, and reveals divergent serotype specific sub-populations and distant ancestors. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2016, 10, e0004861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Reference Method for Broth Dilution Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Yeasts, 3rd ed.; CLSI document M27-A3; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Arendrup, M.C.; Cuenca-Estrella, M.; Lass-Florl, C.; Hope, W.; Eucast, A. EUCAST technical note on the EUCAST definitive document EDef 7.2: Method for the determination of broth dilution minimum inhibitory concentrations of antifungal agents for yeasts EDef 7.2 (EUCAST-AFST). Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012, 18, E246–E247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez-Andreu, C.M.; Pimentel-Turino, T.; Martinez-Machin, G.F.; González-Miranda, M. Determinación de la concentración mínima inhibitoria de fluconazol frente a Cryptococcus neoformans. Rev. Cuba. Med. Trop. 1999, 51, 55–57. [Google Scholar]

- Casali, A.K.; Goulart, L.; Rosa e Silva, L.K.; Ribeiro, A.M.; Amaral, A.A.; Alves, S.H.; Schrank, A.; Meyer, W.; Vainstein, M.H. Molecular typing of clinical and environmental Cryptococcus neoformans isolates in the Brazilian state Rio Grande do Sul. FEMS Yeast Res. 2003, 3, 405–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trilles, L.; Lazera, M.; Wanke, B.; Theelen, B.; Boekhout, T. Genetic characterization of environmental isolates of the Cryptococcus neoformans species complex from Brazil. Med. Mycol. 2003, 41, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igreja, R.P.; Lazera Mdos, S.; Wanke, B.; Galhardo, M.C.; Kidd, S.E.; Meyer, W. Molecular epidemiology of Cryptococcus neoformans isolates from AIDS patients of the Brazilian city, Rio de Janeiro. Med. Mycol. 2004, 42, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abegg, M.A.; Cella, F.L.; Faganello, J.; Valente, P.; Schrank, A.; Vainstein, M.H. Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii isolated from the excreta of psittaciformes in a southern Brazilian zoological garden. Mycopathologia 2006, 161, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros Ribeiro, A.; Silva, L.K.; Silveira Schrank, I.; Schrank, A.; Meyer, W.; Henning Vainstein, M. Isolation of Cryptococcus neoformans var. neoformans serotype D from Eucalyptus in South Brazil. Med. Mycol. 2006, 44, 707–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, M.T.; Fusco-Almeida, A.M.; Baeza, L.C.; Melhem Mde, S.; Medes-Giannini, M.J. Genotyping, serotyping and determination of mating-type of Cryptococcus neoformans clinical isolates from São Paulo State, Brazil. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. São Paulo 2007, 49, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugarini, C.; Goebel, C.S.; Condas, L.A.; Muro, M.D.; de Farias, M.R.; Ferreira, F.M.; Vainstein, M.H. Cryptococcus neoformans isolated from Passerine and Psittacine bird excreta in the state of Parana, Brazil. Mycopathologia 2008, 166, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.A.; Ngamskulrungroj, P. Molecular characterization of environmental Cryptococcus neoformans isolated in Vitoria, ES, Brazil. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. São Paulo 2008, 50, 315–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, W.R.; Meyer, W.; Wanke, B.; Costa, S.P.; Trilles, L.; Nascimento, J.L.; Medeiros, R.; Morales, B.P.; Bezerra Cde, C.; Macedo, R.C.; et al. Primary endemic Cryptococcosis gattii by molecular type VGII in the state of Pará, Brazil. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2008, 103, 813–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trilles, L.; Lazera Mdos, S.; Wanke, B.; Oliveira, R.V.; Barbosa, G.G.; Nishikawa, M.M.; Morales, B.P.; Meyer, W. Regional pattern of the molecular types of Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii in Brazil. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2008, 103, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa Sdo, P.; Lazera Mdos, S.; Santos, W.R.; Morales, B.P.; Bezerra, C.C.; Nishikawa, M.M.; Barbosa, G.G.; Trilles, L.; Nascimento, J.L.; Wanke, B. First isolation of Cryptococcus gattii molecular type VGII and Cryptococcus neoformans molecular type VNI from environmental sources in the city of Belem, Para, Brazil. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2009, 104, 662–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade-Silva, L.; Ferreira-Paim, K.; Silva-Vergara, M.L.; Pedrosa, A.L. Molecular characterization and evaluation of virulence factors of Cryptococcus laurentii and Cryptococcus neoformans strains isolated from external hospital areas. Fungal Biol. 2010, 114, 438–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto Junior, V.L.; Pone, M.V.; Pone, S.M.; Campos, J.M.; Garrido, J.R.; de Barros, A.C.; Trilles, L.; Barbosa, G.G.; Morales, B.P.; Bezerra Cde, C.; et al. Cryptococcus gattii molecular type VGII as agent of meningitis in a healthy child in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Report of an autochthonous case. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2010, 43, 746–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, L.K.; Souza Junior, A.H.; Costa, C.R.; Faganello, J.; Vainstein, M.H.; Chagas, A.L.; Souza, A.C.; Silva, M.R. Molecular typing and antifungal susceptibility of clinical and environmental Cryptococcus neoformans species complex isolates in Goiania, Brazil. Mycoses 2010, 53, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira-Paim, K.; Andrade-Silva, L.; Mora, D.J.; Pedrosa, A.L.; Rodrigues, V.; Silva-Vergara, M.L. Genotyping of Cryptococcus neoformans isolated from captive birds in Uberaba, Minas Gerais, Brazil. Mycoses 2011, 54, e294–e300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, L.M.; Wanke, B.; Lazera Mdos, S.; Trilles, L.; Barbosa, G.G.; Macedo, R.C.; Cavalcanti Mdo, A.; Eulalio, K.D.; Castro, J.A.; Silva, A.S.; et al. Genotypes of Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii as agents of endemic cryptococcosis in Teresina, Piaui (northeastern Brazil). Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2011, 106, 725–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, B.K.; Freire, A.K.; Bentes Ados, S.; Sampaio Ide, L.; Santos, L.O.; Dos Santos, M.S.; De Souza, J.V. Characterization of clinical isolates of the Cryptococcus neoformans-Cryptococcus gattii species complex from the Amazonas State in Brazil. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 2012, 29, 40–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, A.K.; dos Santos Bentes, A.; de Lima Sampaio, I.; Matsuura, A.B.; Ogusku, M.M.; Salem, J.I.; Wanke, B.; de Souza, J.V. Molecular characterisation of the causative agents of Cryptococcosis in patients of a tertiary healthcare facility in the state of Amazonas-Brazil. Mycoses 2012, 55, e145–e150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, D.C.; Martins, M.A.; Szeszs, M.W.; Bonfietti, L.X.; Matos, D.; Melhem, M.S. Susceptibility to antifungal agents and genotypes of Brazilian clinical and environmental Cryptococcus gattii strains. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2012, 72, 332–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardoso, P.H.; Baroni Fde, A.; Silva, E.G.; Nascimento, D.C.; Martins Mdos, A.; Szezs, W.; Paula, C.R. Feline nasal granuloma due to Cryptoccocus gattii type VGII. Mycopathologia 2013, 176, 303–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsujisaki, R.A.; Paniago, A.M.; Lima Junior, M.S.; Alencar Dde, S.; Spositto, F.L.; Nunes Mde, O.; Trilles, L.; Chang, M.R. First molecular typing of cryptococcemia-causing cryptococcus in central-west Brazil. Mycopathologia 2013, 176, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anzai, M.C.; Lazera Mdos, S.; Wanke, B.; Trilles, L.; Dutra, V.; de Paula, D.A.; Nakazato, L.; Takahara, D.T.; Simi, W.B.; Hahn, R.C. Cryptococcus gattii VGII in a Plathymenia reticulata hollow in Cuiaba, Mato Grosso, Brazil. Mycoses 2014, 57, 414–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favalessa, O.C.; de Paula, D.A.; Dutra, V.; Nakazato, L.; Tadano, T.; Lazera Mdos, S.; Wanke, B.; Trilles, L.; Walderez Szeszs, M.; Silva, D.; et al. Molecular typing and in vitro antifungal susceptibility of Cryptococcus spp from patients in Midwest Brazil. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2014, 8, 1037–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favalessa, O.C.; Lazera Mdos, S.; Wanke, B.; Trilles, L.; Takahara, D.T.; Tadano, T.; Dias, L.B.; Vieira, A.C.; Novack, G.V.; Hahn, R.C. Fatal Cryptococcus gattii genotype AFLP6/VGII infection in a HIV-negative patient: Case report and a literature review. Mycoses 2014, 57, 639–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, E.; Bonifacio da Silva, M.E.; Martinez, R.; von Zeska Kress, M.R. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis in an immunocompetent patient due to Cryptococcus gattii molecular type VGI in Brazil: A case report and review of literature. Mycoses 2014, 57, 442–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito-Santos, F.; Barbosa, G.G.; Trilles, L.; Nishikawa, M.M.; Wanke, B.; Meyer, W.; Carvalho-Costa, F.A.; Lazera Mdos, S. Environmental isolation of Cryptococcus gattii VGII from indoor dust from typical wooden houses in the deep Amazonas of the Rio Negro basin. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0115866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Headley, S.A.; Di Santis, G.W.; de Alcantara, B.K.; Costa, T.C.; da Silva, E.O.; Pretto-Giordano, L.G.; Gomes, L.A.; Alfieri, A.A.; Bracarense, A.P. Cryptococcus gattii-induced infections in dogs from Southern Brazil. Mycopathologia 2015, 180, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro e Silva, D.M.; Santos, D.C.; Martins, M.A.; Oliveira, L.; Szeszs, M.W.; Melhem, M.S. First isolation of Cryptococcus neoformans genotype VNI MAT-alpha from wood inside hollow trunks of Hymenaea courbaril. Med. Mycol. 2016, 54, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueiredo, T.P.; Lucas, R.C.; Cazzaniga, R.A.; Franca, C.N.; Segato, F.; Taglialegna, R.; Maffei, C.M. Antifungal susceptibility testing and genotyping characterization of Cryptococcus neoformans and gattii isolates from HIV-infected patients of Ribeirao Preto, São Paulo, Brazil. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. São Paulo 2016, 58, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves, G.S.; Freire, A.K.; Bentes Ados, S.; Pinheiro, J.F.; de Souza, J.V.; Wanke, B.; Matsuura, T.; Jackisch-Matsuura, A.B. Molecular typing of environmental Cryptococcus neoformans/C. gattii species complex isolates from Manaus, Amazonas, Brazil. Mycoses 2016, 59, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herkert, P.F.; Hagen, F.; de Oliveira Salvador, G.L.; Gomes, R.R.; Ferreira, M.S.; Vicente, V.A.; Muro, M.D.; Pinheiro, R.L.; Meis, J.F.; Queiroz-Telles, F. Molecular characterisation and antifungal susceptibility of clinical Cryptococcus deuterogattii (AFLP6/VGII) isolates from Southern Brazil. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2016, 35, 1803–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lomes, N.R.; Melhem, M.S.; Szeszs, M.W.; Martins Mdos, A.; Buccheri, R. Cryptococcosis in non-HIV/non-transplant patients: A Brazilian case series. Med. Mycol. 2016, 54, 669–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souto, A.C.; Bonfietti, L.X.; Ferreira-Paim, K.; Trilles, L.; Martins, M.; Ribeiro-Alves, M.; Pham, C.D.; Martins, L.; Dos Santos, W.; Chang, M.; et al. Population genetic analysis reveals a high genetic diversity in the Brazilian Cryptococcus gattii VGII population and shifts the global origin from the Amazon rainforest to the semi-arid desert in the Northeast of Brazil. PLoS Negl. Trop Dis. 2016, 10, e0004885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar, P.; Pedroso, R.D.S.; Borges, A.S.; Moreira, T.A.; Araujo, L.B.; Roder, D. The epidemiology of cryptococcosis and the characterization of Cryptococcus neoformans isolated in a Brazilian University Hospital. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. São Paulo 2017, 59, e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, E.C.; Guerra, J.M.; Torres, L.N.; Lacerda, A.M.; Gomes, R.G.; Rodrigues, D.M.; Ressio, R.A.; Melville, P.A.; Martin, C.C.; Benesi, F.J.; et al. Cryptococcus gattii molecular type VGII infection associated with lung disease in a goat. BMC Vet. Res. 2017, 13, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Abreu, D.P.B.; Machado, C.H.; Makita, M.T.; Botelho, C.F.M.; Oliveira, F.G.; da Veiga, C.C.P.; Martins, M.D.A.; Baroni, F.A. Intestinal Lesion in a Dog Due to Cryptococcus gattii Type VGII and Review of Published Cases of Canine Gastrointestinal Cryptococcosis. Mycopathologia 2017, 182, 597–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho Santana, R.; Schiave, L.A.; Dos Santos Quaglio, A.S.; de Gaitani, C.M.; Martinez, R. Fluconazole non-susceptible Cryptococcus neoformans, relapsing/refractory cryptococcosis and long-term use of liposomal amphotericin B in an AIDS patient. Mycopathologia 2017, 182, 855–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira-Paim, K.; Andrade-Silva, L.; Fonseca, F.M.; Ferreira, T.B.; Mora, D.J.; Andrade-Silva, J.; Khan, A.; Dao, A.; Reis, E.C.; Almeida, M.T.; et al. MLST-based population genetic analysis in a global context reveals clonality amongst Cryptococcus neoformans var. grubii VNI isolates from HIV patients in Southeastern Brazil. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2017, 11, e0005223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maciel, R.A.; Ferreira, L.S.; Wirth, F.; Rosa, P.D.; Aves, M.; Turra, E.; Goldani, L.Z. Corticosteroids for the management of severe intracranial hypertension in meningoencephalitis caused by Cryptococcus gattii: A case report and review. J. Mycol. Med. 2017, 27, 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade-Silva, L.E.; Ferreira-Paim, K.; Ferreira, T.B.; Vilas-Boas, A.; Mora, D.J.; Manzato, V.M.; Fonseca, F.M.; Buosi, K.; Andrade-Silva, J.; Prudente, B.D.S.; et al. Genotypic analysis of clinical and environmental Cryptococcus neoformans isolates from Brazil reveals the presence of VNB isolates and a correlation with biological factors. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0193237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianchi, R.M.; Santana de Cecco, B.; Schwerts, C.I.; Panziera, W.; Pinto de Andrade, C.; Spanamberg, A.; Ravazzolo, A.P.; Ferreiro, L.; Driemeier, D. Pneumonia by Cryptococcus neoformans in a goat in the Southern region of Brazil. Cienc. Rural. 2018, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herkert, P.F.; Meis, J.F.; Lucca de Oliveira Salvador, G.; Rodrigues Gomes, R.; Aparecida Vicente, V.; Dominguez Muro, M.; Lameira Pinheiro, R.; Lopes Colombo, A.; Vargas Schwarzbold, A.; Sakuma de Oliveira, C.; et al. Molecular characterization and antifungal susceptibility testing of Cryptococcus neoformans sensu stricto from southern Brazil. J. Med. Microbiol. 2018, 67, 560–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, J.O.; Tsujisaki, R.A.S.; Nunes, M.O.; Lima, G.M.E.; Paniago, A.M.M.; Pontes, E.; Chang, M.R. Cryptococcal meningitis epidemiology: 17 years of experience in a State of the Brazilian Pantanal. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2018, 51, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, D.F.S.; Cruz, K.S.; Santos, C.; Menescal, L.S.F.; Neto, J.; Pinheiro, S.B.; Silva, L.M.; Trilles, L.; Braga de Souza, J.V. MLST reveals a clonal population structure for Cryptococcus neoformans molecular type VNI isolates from clinical sources in Amazonas, Northern-Brazil. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0197841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wirth, F.; Azevedo, M.I.; Goldani, L.Z. Molecular types of Cryptococcus species isolated from patients with cryptococcal meningitis in a Brazilian tertiary care hospital. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2018, 22, 495–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brito-Santos, F.; Reis, R.S.; Coelho, R.A.; Almeida-Paes, R.; Pereira, S.A.; Trilles, L.; Meyer, W.; Wanke, B.; Lazera, M.D.S.; Gremiao, I.D.F. Cryptococcosis due to Cryptococcus gattii VGII in southeast Brazil: The One Health approach revealing a possible role for domestic cats. Med. Mycol. Case Rep. 2019, 24, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damasceno-Escoura, A.H.; de Souza, M.L.; de Oliveira Nunes, F.; Pardi, T.C.; Gazotto, F.C.; Florentino, D.H.; Mora, D.J.; Silva-Vergara, M.L. Epidemiological, clinical and outcome aspects of patients with cryptococcosis caused by Cryptococcus gattii from a non-endemic area of Brazil. Mycopathologia 2019, 184, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos Bentes, A.; Wanke, B.; Dos Santos Lazera, M.; Freire, A.K.L.; da Silva Junior, R.M.; Rocha, D.F.S.; Pinheiro, S.B.; Zelski, S.E.; Matsuura, A.B.J.; da Rocha, L.C.; et al. Cryptococcus gattii VGII isolated from native forest and river in Northern Brazil. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2019, 50, 495–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maruyama, F.H.; de Paula, D.A.J.; Menezes, I.G.; Favalessa, O.C.; Hahn, R.C.; de Almeida, A.; Sousa, V.R.F.; Nakazato, L.; Dutra, V. Genetic diversity of the Cryptococcus gattii species complex in Mato Grosso State, Brazil. Mycopathologia 2019, 184, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponzio, V.; Chen, Y.; Rodrigues, A.M.; Tenor, J.L.; Toffaletti, D.L.; Medina-Pestana, J.O.; Colombo, A.L.; Perfect, J.R. Genotypic diversity and clinical outcome of cryptococcosis in renal transplant recipients in Brazil. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2019, 8, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vechi, H.T.; Theodoro, R.C.; de Oliveira, A.L.; Gomes, R.; Soares, R.D.A.; Freire, M.G.; Bay, M.B. Invasive fungal infection by Cryptococcus neoformans var. grubii with bone marrow and meningeal involvement in a HIV-infected patient: A case report. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito-Santos, F.; Trilles, L.; Firacative, C.; Wanke, B.; Carvalho-Costa, F.A.; Nishikawa, M.M.; Campos, J.P.; Junqueira, A.C.V.; Souza, A.C.; Lazera, M.D.S.; et al. Indoor dust as a source of virulent strains of the agents of cryptococcosis in the Rio Negro Micro-Region of the Brazilian Amazon. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, L.B.; Bock, D.; Klafke, G.B.; Sanchotene, K.O.; Basso, R.P.; Benelli, J.L.; Poester, V.R.; da Silva, F.A.; Trilles, L.; Severo, C.B.; et al. Cryptococcosis in HIV-AIDS patients from Southern Brazil: Still a major problem. J. Mycol. Med. 2020, 30, 101044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grizante Bariao, P.H.; Tonani, L.; Cocio, T.A.; Martinez, R.; Nascimento, E.; von Zeska Kress, M.R. Molecular typing, in vitro susceptibility and virulence of Cryptococcus neoformans/Cryptococcus gattii species complex clinical isolates from south-eastern Brazil. Mycoses 2020, 63, 1341–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, S.B.; Sousa, E.S.; Cortez, A.C.A.; da Silva Rocha, D.F.; Menescal, L.S.F.; Chagas, V.S.; Gomez, A.S.P.; Cruz, K.S.; Santos, L.O.; Alves, M.J.; et al. Cryptococcal meningitis in non-HIV patients in the State of Amazonas, Northern Brazil. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.M.; Ferreira, W.A.; Filho, R.; Lacerda, M.V.G.; Ferreira, G.M.A.; Saunier, M.N.; Macedo, M.M.; Cristo, D.A.; Alves, M.J.; Jackisch-Matsuura, A.B.; et al. New ST623 of Cryptococcus neoformans isolated from a patient with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in the Brazilian Amazon. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2020, 19, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilas-Boas, A.M.; Andrade-Silva, L.E.; Ferreira-Paim, K.; Mora, D.J.; Ferreira, T.B.; Santos, D.A.; Borges, A.S.; Melhem, M.S.C.; Silva-Vergara, M.L. High genetic variability of clinical and environmental Cryptococcus gattii isolates from Brazil. Med. Mycol. 2020, 58, 1126–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escandón, P.; Sánchez, A.; Martinez, M.; Meyer, W.; Castaneda, E. Molecular epidemiology of clinical and environmental isolates of the Cryptococcus neoformans species complex reveals a high genetic diversity and the presence of the molecular type VGII mating type a in Colombia. FEMS Yeast Res. 2006, 6, 625–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escandón, P.; Sánchez, A.; Firacative, C.; Castaneda, E. Isolation of Cryptococcus gattii molecular type VGIII, from Corymbia ficifolia detritus in Colombia. Med. Mycol. 2010, 48, 675–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firacative, C.; Torres, G.; Rodriguez, M.C.; Escandon, P. First environmental isolation of Cryptococcus gattii serotype B, from Cucuta, Colombia. Biomedica 2011, 31, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lizarazo, J.; Chaves, O.; Peña, Y.; Escandón, P.; Agudelo, C.I.; Castañeda, E. Comparación de los hallazgos clínicos y de supervivencia entre pacientes VIH positivos y VIH negativos con criptococosis meníngea en un hospital del tercer nivel. Acta Médica. Colomb. 2012, 37, 49–61. [Google Scholar]

- Lizarazo, J.; Escandón, P.; Agudelo, C.I.; Castañeda, E. Cryptococcosis in Colombian children and literature review. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2014, 109, 797–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lizarazo, J.; Escandón, P.; Agudelo, C.I.; Firacative, C.; Meyer, W.; Castañeda, E. Retrospective study of the epidemiology and clinical manifestations of Cryptococcus gattii infections in Colombia from 1997-2011. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2014, 8, e3272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguera, M.C.; Escandón, P.; Castañeda, E. Cryptococcosis in Atlantico, Colombia: An approximation of the prevalence of this mycosis and the distribution of the etiological agent in the environment. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2015, 48, 580–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cogliati, M.; Zani, A.; Rickerts, V.; McCormick, I.; Desnos-Ollivier, M.; Velegraki, A.; Escandon, P.; Ichikawa, T.; Ikeda, R.; Bienvenu, A.L.; et al. Multilocus sequence typing analysis reveals that Cryptococcus neoformans var. neoformans is a recombinant population. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2016, 87, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguera, M.C.; Escandon, P.; Castaneda, E. Fatal Cryptococcus gattii genotype VGI infection in an HIV-positive patient in Barranquilla, Colombia. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. São Paulo 2017, 59, e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vélez, N.; Escandón, P. Report on novel environmental niches for Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii in Colombia: Tabebuia guayacan and Roystonea regia. Med. Mycol. 2017, 55, 794–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anacona, C.; González, C.F.E.; Vásquez-A., L.R.; Escandón, P. First isolation and molecular characterization of Cryptococcus neoformans var. grubii in excreta of birds in the urban perimeter of the Municipality of Popayan, Colombia. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 2018, 35, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virviescas, B.C.; Aragón, M.; Vásquez, A.L.; González, F.; Escandón, P.; Castro, H. Molecular characterization of Cryptococcus neoformans recovered from pigeon droppings in Rivera and Neiva, Colombia. Rev. MVZ Córdoba 2018, 23, 6991–6997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angarita-Sánchez, A.; Cárdenas-Sierra, D.; Parra-Giraldo, C.; Diaz-Carvajal, C.; Escandón-Hernández, P. Recuperación de Cryptococcus neoformans y C. gattii ambientales y su asociación con aislados clínicos en Cúcuta, Colombia. Rev. MVZ Córdoba 2019, 24, 7137–7144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firacative, C.; Torres, G.; Meyer, W.; Escandon, P. Clonal dispersal of Cryptococcus gattii VGII in an endemic region of cryptococcosis in Colombia. J. Fungi 2019, 5, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noguera, M.C.; Escandón, P.; Arévalo, M.; García, Y.; Suárez, L.E.; Castañeda, E. Prevalence of cryptococcosis in Atlántico, department of Colombia assessed with an active epidemiological search. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2019, 52, e20180194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguera, M.C.; Escandón, P.; Arévalo, M.; Piedrahita, J.; Castañeda, E. Fatal neurocryptococcosis in a Colombian underage patient. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2019, 13, 1072–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velez, N.; Escandon, P. Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) of clinical and environmental isolates of Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii in six departments of Colombia reveals high genetic diversity. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2020, 53, e20190422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refojo, N.; Perrotta, D.; Brudny, M.; Abrantes, R.; Hevia, A.I.; Davel, G. Isolation of Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii from trunk hollows of living trees in Buenos Aires City, Argentina. Med. Mycol. 2009, 47, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattana, M.E.; Tracogna, M.F.; Fernandez, M.S.; Carol Rey, M.C.; Sosa, M.A.; Giusiano, G.E. [Genotyping of Cryptococcus neoformans/Cryptococcus gattii complex clinical isolates from Hospital "Dr. Julio, C. Perrando", Resistencia city (Chaco, Argentina)]. Rev. Argent. Microbiol. 2013, 45, 89–92. [Google Scholar]

- Mazza, M.; Refojo, N.; Bosco-Borgeat, M.E.; Taverna, C.G.; Trovero, A.C.; Roge, A.; Davel, G. Cryptococcus gattii in urban trees from cities in North-eastern Argentina. Mycoses 2013, 56, 646–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattana, M.E.; Sosa Mde, L.; Fernandez, M.; Rojas, F.; Mangiaterra, M.; Giusiano, G. Native trees of the Northeast Argentine: Natural hosts of the Cryptococcus neoformans-Cryptococcus gattii species complex. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 2014, 31, 188–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattana, M.E.; Fernandez, M.S.; Rojas, F.D.; Sosa Mde, L.; Giusiano, G. [Genotypes and epidemiology of clinical isolates of Cryptococcus neoformans in Corrientes, Argentina]. Rev. Argent. Microbiol. 2015, 47, 82–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Cicora, F.; Petroni, J.; Formosa, P.; Roberti, J. A rare case of Cryptococcus gattii pneumonia in a renal transplant patient. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 2015, 17, 463–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arechavala, A.; Negroni, R.; Messina, F.; Romero, M.; Marín, E.; Depardo, R.; Walker, L.; Santiso, G. Cryptococcosis in an Infectious Diseases Hospital of Buenos Aires, Argentina. Revision of 2041 cases: Diagnosis, clinical features and therapeutics. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 2018, 35, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berejnoi, A.; Taverna, C.G.; Mazza, M.; Vivot, M.; Isla, G.; Cordoba, S.; Davel, G. First case report of cryptococcosis due to Cryptococcus decagattii in a pediatric patient in Argentina. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2019, 52, e20180419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiso, G.M.; Messina, F.; Gallo, A.; Marin, E.; Depardo, R.; Arechavala, A.; Walker, L.; Negroni, R.; Romero, M.M. Tongue lesion due to Cryptococcus neoformans as the first finding in an HIV-positive patient. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taverna, C.G.; Bosco-Borgeat, M.E.; Mazza, M.; Vivot, M.E.; Davel, G.; Canteros, C.E.; AGC. Frequency and geographical distribution of genotypes and mating types of Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii species complexes in Argentina. Rev. Argent. Microbiol. 2020, 52, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivares, L.R.; Martinez, K.M.; Cruz, R.M.; Rivera, M.A.; Meyer, W.; Espinosa, R.A.; Martinez, R.L.; Santos, G.M. Genotyping of Mexican Cryptococcus neoformans and C. gattii isolates by PCR-fingerprinting. Med. Mycol. 2009, 47, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, G.M.; Casillas-Vega, N.; Garza-Gonzalez, E.; Hernandez-Bello, R.; Rivera, G.; Rodriguez, J.A.; Bocanegra-Garcia, V. Molecular typing of clinical isolates of Cryptococcus neoformans/Cryptococcus gattii species complex from Northeast Mexico. Folia Microbiol. 2016, 61, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Illnait-Zaragozi, M.T.; Martinez-Machin, G.F.; Fernandez-Andreu, C.M.; Boekhout, T.; Meis, J.F.; Klaassen, C.H. Microsatellite typing of clinical and environmental Cryptococcus neoformans var. grubii isolates from Cuba shows multiple genetic lineages. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e9124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illnait-Zaragozi, M.T.; Hagen, F.; Fernandez-Andreu, C.M.; Martinez-Machin, G.F.; Polo-Leal, J.L.; Boekhout, T.; Klaassen, C.H.; Meis, J.F. Reactivation of a Cryptococcus gattii infection in a cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus) held in the National Zoo, Havana, Cuba. Mycoses 2011, 54, e889–e892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illnait-Zaragozi, M.T.; Ortega-Gonzalez, L.M.; Hagen, F.; Martinez-Machin, G.F.; Meis, J.F. Fatal Cryptococcus gattii genotype AFLP5 infection in an immunocompetent Cuban patient. Med. Mycol. Case Rep. 2013, 2, 48–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvo, B.M.; Colombo, A.L.; Fischman, O.; Santiago, A.; Thompson, L.; Lazera, M.; Telles, F.; Fukushima, K.; Nishimura, K.; Tanaka, R.; et al. Antifungal susceptibilities, varieties, and electrophoretic karyotypes of clinical isolates of Cryptococcus neoformans from Brazil, Chile, and Venezuela. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2001, 39, 2348–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, G.; Panizo, M.M.; Urdaneta, E.; Alarcón, V.; García, N.; Moreno, X.; Capote, A.M.; Reviakina, V.; Dolande, M. Characterization by PCR-RFLP of the Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii species complex in Venezuela. Investig. Clin. 2018, 59, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejar, V.; Tello, M.; Garcia, R.; Guevara, J.M.; Gonzales, S.; Vergaray, G.; Valencia, E.; Abanto, E.; Ortega-Loayza, A.G.; Hagen, F.; et al. Molecular characterization and antifungal susceptibility of Cryptococcus neoformans strains collected from a single institution in Lima, Peru. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 2015, 32, 88–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van de Wiele, N.; Neyra, E.; Firacative, C.; Gilgado, F.; Serena, C.; Bustamante, B.; Meyer, W. Molecular epidemiology reveals low genetic diversity among Cryptococcus neoformans isolates from people living with HIV in Lima, Peru, during the Pre-HAART era. Pathogens 2020, 9, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata-Delgado, C.; Lozada-Alvarado, S.; Gross, N.T.; Jaikel-Víquez, D. Caracterización fenotípica y genotípica de aislamientos clínicos de los complejos de especies Cryptococcus neoformans y Cryptococcus gattii en Costa Rica. Rev. Panam. Enferm. Infecc. 2019, 2, 58–63. [Google Scholar]

- Sánches, S.; Zambrano, D.; García, M.; Bedoya, C.; Fernández, C.; Illnait-Zaragozi, M.T. Caracterización molecular de los aislamientos de Cryptococcus neoformans de pacientes con HIV, Guayaquil, Ecuador. Biomedica 2017, 37, 425–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra-Vera, H.J.; Espinoza, W.A.; Godoy-Martínez, P.; Silva-Rojas, G.A.; Aguilar-Buele, E.A.; Farfán-Cano, G.G.; Buele, C.D. Primer reporte de Cryptococcus gattii en Ecuador. Revista Científica INSPILIP 2019, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Solar, S.; Diaz, V.; Rosas, R.; Valenzuela, S.; Pires, Y.; Diaz, M.; Noriega, L.; Porte, L.; Weitzel, T.; Thompson, L. Infección de sistema nervioso central por Cryptococcus gattii en paciente inmunocompetente: Desafíos diagnósticos y terapéuticos en un Centro Terciario de Referencia de Paciente Internacional en Santiago de Chile. INFOCUS 2015, 4, 116. [Google Scholar]

- Vieille, P.; Cruz, R.; Leon, P.; Caceres, N.; Giusiano, G. Isolation of Cryptococcus gattii VGIII from feline nasal injury. Med. Mycol. Case Rep. 2018, 22, 55–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, L.; Porte, L.; Diaz, V.; Diaz, M.C.; Solar, S.; Valenzuela, P.; Norley, N.; Pires, Y.; Carreno, F.; Valenzuela, S.; et al. Cryptococcus bacillisporus (VGIII) meningoencephalitis acquired in Santa Cruz, Bolivia. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engelthaler, D.M.; Hicks, N.D.; Gillece, J.D.; Roe, C.C.; Schupp, J.M.; Driebe, E.M.; Gilgado, F.; Carriconde, F.; Trilles, L.; Firacative, C.; et al. Cryptococcus gattii in North American Pacific Northwest: Whole-population genome analysis provides insights into species evolution and dispersal. MBio 2014, 5, e01464-14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aminnejad, M.; Cogliati, M.; Duan, S.; Arabatzis, M.; Tintelnot, K.; Castaneda, E.; Lazera, M.; Velegraki, A.; Ellis, D.; Sorrell, T.C.; et al. Identification and characterization of VNI/VNII and novel VNII/VNIV hybrids and impact of hybridization on virulence and antifungal susceptibility within the C. neoformans/C. gattii species complex. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0163955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aminnejad, M.; Diaz, M.; Arabatzis, M.; Castañeda, E.; Lazera, M.; Velegraki, A.; Marriott, D.; Sorrell, T.C.; Meyer, W. Identification of novel hybrids between Cryptococcus neoformans var. grubii VNI and Cryptococcus gattii VGII. Mycopathologia 2012, 173, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velez, N.; Alvarado, M.; Parra-Giraldo, C.M.; Sanchez-Quitian, Z.A.; Escandon, P.; Castaneda, E. Genotypic diversity is independent of pathogenicity in Colombian strains of Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii in Galleria mellonella. J. Fungi 2018, 4, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walraven, C.J.; Gerstein, W.; Hardison, S.E.; Wormley, F.; Lockhart, S.R.; Harris, J.R.; Fothergill, A.; Wickes, B.; Gober-Wilcox, J.; Massie, L.; et al. Fatal disseminated Cryptococcus gattii infection in New Mexico. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e28625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firacative, C.; Trilles, L.; Meyer, W. MALDI-TOF MS enables the rapid identification of the major molecular types within the Cryptococcus neoformans/C. gattii species complex. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e37566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagen, F.; Colom, M.F.; Swinne, D.; Tintelnot, K.; Iatta, R.; Montagna, M.T.; Torres-Rodriguez, J.M.; Cogliati, M.; Velegraki, A.; Burggraaf, A.; et al. Autochthonous and dormant Cryptococcus gattii infections in Europe. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2012, 18, 1618–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcellos, V.A.; Martins, L.M.S.; Fontes, A.C.L.; Reuwsaat, J.C.V.; Squizani, E.D.; de Sousa Araujo, G.R.; Frases, S.; Staats, C.C.; Schrank, A.; Kmetzsch, L.; et al. Genotypic and phenotypic diversity of Cryptococcus gattii VGII clinical isolates and its impact on virulence. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidd, S.E.; Hagen, F.; Tscharke, R.L.; Huynh, M.; Bartlett, K.H.; Fyfe, M.; Macdougall, L.; Boekhout, T.; Kwon-Chung, K.J.; Meyer, W. A rare genotype of Cryptococcus gattii caused the cryptococcosis outbreak on Vancouver Island (British Columbia, Canada). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 17258–17263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Emergence of Cryptococcus gattii-Pacific Northwest, 2004–2010. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2010, 59, 865–868. [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett, K.H.; Cheng, P.Y.; Duncan, C.; Galanis, E.; Hoang, L.; Kidd, S.; Lee, M.K.; Lester, S.; MacDougall, L.; Mak, S.; et al. A decade of experience: Cryptococcus gattii in British Columbia. Mycopathologia 2012, 173, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Severo, C.B.; Xavier, M.O.; Gazzoni, A.F.; Severo, L.C. Cryptococcosis in children. Paediatr. Respir. Rev. 2009, 10, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darze, C.; Lucena, R.; Gomes, I.; Melo, A. [The clinical laboratory characteristics of 104 cases of cryptococcal meningoencephalitis]. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2000, 33, 21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Correa Mdo, P.; Oliveira, E.C.; Duarte, R.R.; Pardal, P.P.; Oliveira Fde, M.; Severo, L.C. Cryptococcosis in children in the State of Para, Brazil. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 1999, 32, 505–508. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, D.H.; Pfeiffer, T.J. Natural habitat of Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1990, 28, 1642–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazera, M.S.; Pires, F.D.; Camillo-Coura, L.; Nishikawa, M.M.; Bezerra, C.C.; Trilles, L.; Wanke, B. Natural habitat of Cryptococcus neoformans var. neoformans in decaying wood forming hollows in living trees. J. Med. Vet. Mycol. 1996, 34, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazera, M.S.; Cavalcanti, M.A.; Trilles, L.; Nishikawa, M.M.; Wanke, B. Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii-evidence for a natural habitat related to decaying wood in a pottery tree hollow. Med. Mycol. 1998, 36, 119–122. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, T.G.; Castañeda, E.; Nielsen, K.; Wanke, B.; Lazéra, M.S. Environmental Niches for Cryptococcus Neoformans and Cryptococcus ga$ttii. In Cryptococcus: From Human Pathogen to Model Yeast; Heitman, J., Kozel, T.R., Kwon-Chung, J.K., Perfect, J.R., Casadevall, A., Eds.; ASM Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Granados, D.P.; Castañeda, E. Influence of climatic conditions on the isolation of members of the Cryptococcus neoformans species complex from trees in Colombia from 1992–2004. FEMS Yeast Res. 2006, 6, 636–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escandón, P.; Quintero, E.; Granados, D.; Huerfano, S.; Ruiz, A.; Castañeda, E. [Isolation of Cryptococcus gattii serotype B from detritus of Eucalyptus trees in Colombia]. Biomedica 2005, 25, 390–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, R.; Krockenberger, M.B.; O’Brien, C.R.; Carter, D.; Meyer, W.; Canfield, P.J. Veterinary Insights into Cryptococcosis Caused by Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii. In Cryptococcus: From Human Pathogen to Model Yeast; Heitman, J., Kozel, T.R., Kwon-Chung, K.J., Perfect, J.R., Eds.; American Society for Microbiology: Herndon, VA, USA, 2010; pp. 489–504. [Google Scholar]

- Krockenberger, M.; Stalder, K.; Malik, R.; Canfield, P. Cryptococcosis in Australian Wildlife. Microbiol. Aust. 2005, 26, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockhart, S.R.; Iqbal, N.; Harris, J.R.; Grossman, N.T.; DeBess, E.; Wohrle, R.; Marsden-Haug, N.; Vugia, D.J. Cryptococcus gattii in the United States: Genotypic diversity of human and veterinary isolates. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e74737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, L.M.; Meyer, W.; Firacative, C.; Thompson, G.R., 3rd; Samitz, E.; Sykes, J.E. Antifungal drug susceptibility and phylogenetic diversity among Cryptococcus isolates from dogs and cats in North America. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2014, 52, 2061–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvintseva, A.P.; Marra, R.E.; Nielsen, K.; Heitman, J.; Vilgalys, R.; Mitchell, T.G. Evidence of sexual recombination among Cryptococcus neoformans serotype A isolates in sub-Saharan Africa. Eukaryot. Cell 2003, 2, 1162–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litvintseva, A.P.; Carbone, I.; Rossouw, J.; Thakur, R.; Govender, N.P.; Mitchell, T.G. Evidence that the human pathogenic fungus Cryptococcus neoformans var. grubii may have evolved in Africa. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e19688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.C.; Meyer, W.; Sorrell, T.C. Cryptococcus gattii infections. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2014, 27, 980–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| C. neoformans Species Complex | C. gattii Species Complex | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country [Ref] | n | Source | VNI | VNII | VNIII | VNIV | VGI | VGII | VGIII | VGIV | Total |

| Brazil [18,20,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92] | 2762 1 | Cli | 1537 2 | 91 | - | 2 | 21 | 409 2,3 | 18 | - | 2078 |

| Env | 365 | 16 | 1 | 23 | 7 | 242 3 | - | - | 654 | ||

| Vet | 3 | - | - | - | - | 14 | - | - | 17 | ||

| Colombia [18,32,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109] | 1436 | Cli | 396 3 | 19 3 | - | 6 | 12 | 64 2,3 | 40 | 2 | 539 |

| Env | 686 | 6 | - | - | 4 2 | 107 2 | 83 | 11 | 897 | ||

| Argentina [18,20,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119] | 644 | Cli | 532 | 15 | 31 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 2 3 | - | 600 |

| Env | 19 | - | - | - | 23 | 2 | - | 44 | |||

| Mexico [18,32,120,121] | 321 | Cli | 209 | 21 | 12 | 7 | 11 | 5 | 26 2 | 7 | 298 |

| Env | 18 | - | - | - | - | - | 5 | - | 23 | ||

| Cuba [17,35,122,123,124] | 247 | Cli | 141 | - | - | 36 | - | - | 1 | - | 178 |

| Env | 68 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 68 | ||

| Vet | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | ||

| Venezuela [18,32,125,126] | 101 | Cli | 70 | 10 | 1 | - | 5 | 12 | 3 | - | 101 |

| Peru [18,127,128] | 85 | Cli | 64 | 16 | 2 | 2 | 1 | - | - | - | 85 |

| Costa Rica [129] | 36 | Cli | 22 | 11 | - | - | 2 | - | - | 1 | 36 |

| Ecuador [130,131] | 28 | Cli | 27 | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | 28 |

| Chile [18,125,132,133] | 20 | Cli | 4 | 3 | 3 | 5 | - | - | - | - | 15 |

| Env | 4 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 4 | ||

| Vet | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | ||

| Guatemala [18] | 15 | Cli | 14 | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | 15 |

| Bolivia [134] | 1 | Cli | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 |

| Honduras [15] | 1 | Cli | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | 1 |

| Paraguay [32] | 1 | Cli | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 |

| Uruguay [135] | 1 | Env | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | 1 |

| Cli | 3022 | 186 | 49 | 64 | 60 | 492 | 93 | 10 | 3976 | ||

| Env | 1160 | 22 | 1 | 23 | 34 | 350 | 90 | 11 | 1691 | ||

| Vet | 3 | - | - | - | 1 | 14 | 1 | - | 19 | ||

| Total | 4185 | 208 | 50 | 87 | 95 | 856 | 184 | 21 | 5686 | ||

| Population Group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species Complex | MT | Clinical | Environmental | Veterinary | Total |

| C. neoformans | VNI | 262 | 76 | - | 344 2 |

| VNB | - | 5 | - | 5 | |

| VNII | 12 | - | - | 12 | |

| VNIV | 6 | - | - | 6 | |

| n of isolates | 280 | 81 | - | 367 2 | |

| n of STs | 34 | 16 | - | 41 | |

| D1 | 0.6149 | 0.7247 | - | 0.7104 | |

| C. gattii | VGI | 28 | 2 | 1 | 31 |

| VGII | 207 | 82 | 10 | 299 | |

| VGIII | 37 | 32 | - | 69 | |

| VGIV | 1 | - | - | 1 | |

| n of isolates | 273 | 116 | 11 | 400 | |

| n of STs | 125 | 116 | 8 | 149 | |

| D1 | 0.9806 | 0.9195 | 0.9273 | 0.9755 | |

| Amphotericin-B (µg/mL) | 5-Fluorocytosine (µg/mL) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MT | n | Range | GM | Range | GM | Ref. |

| VNI | 99 | 0.016–0.125 | 0.099 | 0.25–8 | 2.519 | [77] 1 |

| 26 | 0.03–0.25 | 0.060 | [79] 1 | |||

| 18 | 0.03–1 | - | 0.125–4 | - | [89] 1 | |

| 75 | 0.03–2 | 0.348 | [116] 1 | |||

| 19 | 0.125–0.25 | - | 0.5–8 | - | [17] 1 | |

| 7 | 0.125–0.25 | - | [65] 2 | |||

| 1 | 0.125 | - | [72] 2 | |||

| 17 | 0.5–1 | 0.670 | 0.5–8 | 2.770 | [58] 1 | |

| 1 | 0.5 | - | 2 | - | [91] 5 | |

| VNII | 2 | 0.12 | 0.120 | [116] 1 | ||

| VNIII | 4 | 0.06–0.5 | 0.173 | [116] 1 | ||

| VGI | 1 | 0.06 | - | 8 | - | [60] 1 |

| 4 | 0.125–0.5 | 0.290 | [54] 3 | |||

| 1 | 0.125 | - | 8 | - | [123] 1 | |

| 1 | 0.125 | - | 0.5 | - | [124] 1 | |

| VGII | 4 | 0.03–0.125 | 0.060 | [79] 1 | ||

| 7 | 0.03–0.25 | - | [90] 1 | |||

| 8 | 0.03–0.5 | 0.105 | 0.5–2 | 0.771 | [89] 1 | |

| 18 | 0.06–0.25 | 0.079 | 1–8 | 3.700 | [66] 1 | |

| 50 | 0.125–0.5 | 0.390 | [54] 3 | |||

| 2 | 0.125 | - | 2–4 | - | [81] 1 | |

| 1 | 0.19 | - | [65] 2 | |||

| 10 | 0.5–1 | 0.710 | 1–16 | 4.92 | [58] 1 | |

| 1 | 0.5 | - | 8 | - | [59] 1 | |

| VGIII | 54 | 0.125–2 | 0.030 | 0.5–8 | 2.095 | [32] 4 |

| 1 | 0.125 | - | 4 | - | [134] 1 | |

| 2 | 0.25 | - | [117] 3 | |||

| Fluconazole (µg/mL) | Itraconazole (µg/mL) | Voriconazole (µg/mL) | Posaconazole (µg/mL) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MT | n | Range | GM | Range | GM | Range | GM | Range | GM | Ref. |

| VNI | 99 | 0.125–8 | 0.521 | <0.016–0.25 | 0.026 | <0.016–0.125 | 0.022 | <0.016–0.125 | 0.027 | [77] 1 |

| 75 | 0.125–32 | 2.971 | [116] 1 | |||||||

| 19 | 0.25–8 | - | <0.016–0.5 | - | <0.016–0.25 | - | 0.016–0.125 | - | [17] 1 | |

| 51 | 0.25–16 | 7.22 | [85] 1 | |||||||

| 18 | 0.5–16 | - | 0.06–0.25 | - | 0.03–1 | - | [89] 1 | |||

| 17 | 1–16 | 4.34 | 0.03–0.25 | 0.09 | 0.06–0.5 | 0.28 | [58] 1 | |||

| 1 | 1 | - | [91] 6 | |||||||

| 26 | 2–8 | 4.57 | 0.03–0.25 | 0.07 | [79] 1 | |||||

| 7 | 2–48 | - | 0.125–0.5 | - | [65] 3 | |||||

| 19 | 4–>64 | - | [63] 2 | |||||||

| 1 | 32 | - | [72] 3 | |||||||

| VNB | 6 | 4–8 | 6.86 | [85] 1 | ||||||

| VNII | 2 | 1–2 | 1.414 | [116] 1 | ||||||

| 14 | 1–8 | 2.5 | [85] 1 | |||||||

| VNIII | 4 | 2–4 | 2.378 | [116] 1 | ||||||

| VNIV | 36 | 0.125–64 | - | [35] 4 | ||||||

| VGI | 1 | 2 | - | [123] 1 | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | - | 0.125 | - | 0.063 | - | 0.125 | - | [124] 1 | |

| 4 | 4–8 | 5.3 | [54] 2 | |||||||

| 1 | 8 | - | 0.25 | - | 0.5 | - | [60] 1 | |||

| VGII | 18 | 0.5–16 | 2.0785 | 0.031–0.25 | 0.0994 | 0.031–0.25 | 0.0853 | 0.031–0.25 | 0.0853 | [66] 1 |

| 8 | 0.5–16 | 4 | 0.125–0.25 | 0.1777 | 0.0031–1 | 0.148 | [89] 1 | |||

| 7 | 1–8 | - | 0.03–0.125 | - | [90] 1 | |||||

| 10 | 1–16 | 7.46 | 0.03–0.5 | 0.22 | 0.06–0.5 | 0.28 | [58] 1 | |||

| 50 | 1–64 | 12.2 | [54] 2 | |||||||

| 2 | 4–16 | - | 1 | - | 0.12–1 | - | [81] 1 | |||

| 10 | 4–64 | 25.82 | [85] 1 | |||||||

| 4 | 8–32 | 19 | 0.125–0.5 | 0.29 | [79] 1 | |||||

| 1 | 8 | - | 0.25 | - | 0.5 | - | [59] 1 | |||

| 1 | 24 | - | 0.5 | - | [65] 3 | |||||

| VGIII | 54 | 1–128 | 8.239 | <0.015–0.125 | 0.061 | <0.008–1 | 0.033 | 0.015–0.25 | 0.057 | [32] 5 |

| 2 | 4–16 | - | 0.125 | - | 0.06–0.125 | - | [117] 2 | |||

| 1 | 32 | - | 0.25 | - | 0.25 | - | 0.5 | - | [134] 1 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Firacative, C.; Meyer, W.; Castañeda, E. Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii Species Complexes in Latin America: A Map of Molecular Types, Genotypic Diversity, and Antifungal Susceptibility as Reported by the Latin American Cryptococcal Study Group. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 282. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof7040282

Firacative C, Meyer W, Castañeda E. Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii Species Complexes in Latin America: A Map of Molecular Types, Genotypic Diversity, and Antifungal Susceptibility as Reported by the Latin American Cryptococcal Study Group. Journal of Fungi. 2021; 7(4):282. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof7040282

Chicago/Turabian StyleFiracative, Carolina, Wieland Meyer, and Elizabeth Castañeda. 2021. "Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii Species Complexes in Latin America: A Map of Molecular Types, Genotypic Diversity, and Antifungal Susceptibility as Reported by the Latin American Cryptococcal Study Group" Journal of Fungi 7, no. 4: 282. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof7040282

APA StyleFiracative, C., Meyer, W., & Castañeda, E. (2021). Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii Species Complexes in Latin America: A Map of Molecular Types, Genotypic Diversity, and Antifungal Susceptibility as Reported by the Latin American Cryptococcal Study Group. Journal of Fungi, 7(4), 282. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof7040282