Innate Immunity against Cryptococcus, from Recognition to Elimination

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Cryptococcosis

1.2. Host Immune Response

2. Innate Immune Cells

2.1. Macrophages

2.2. Dendritic Cells

2.3. Neutrophils

3. Arsenal of Pattern Recognition Receptors

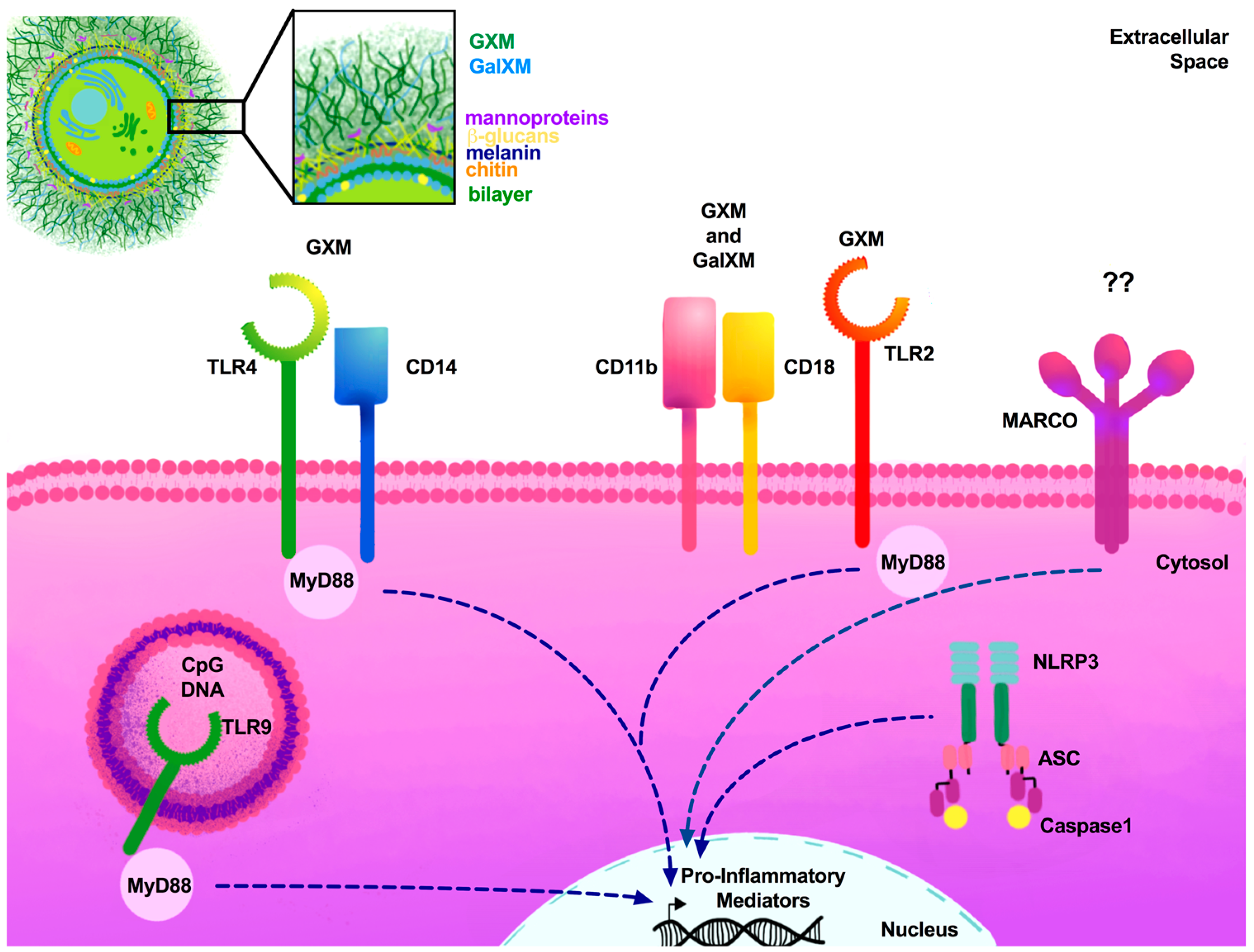

3.1. Toll-Like Receptors

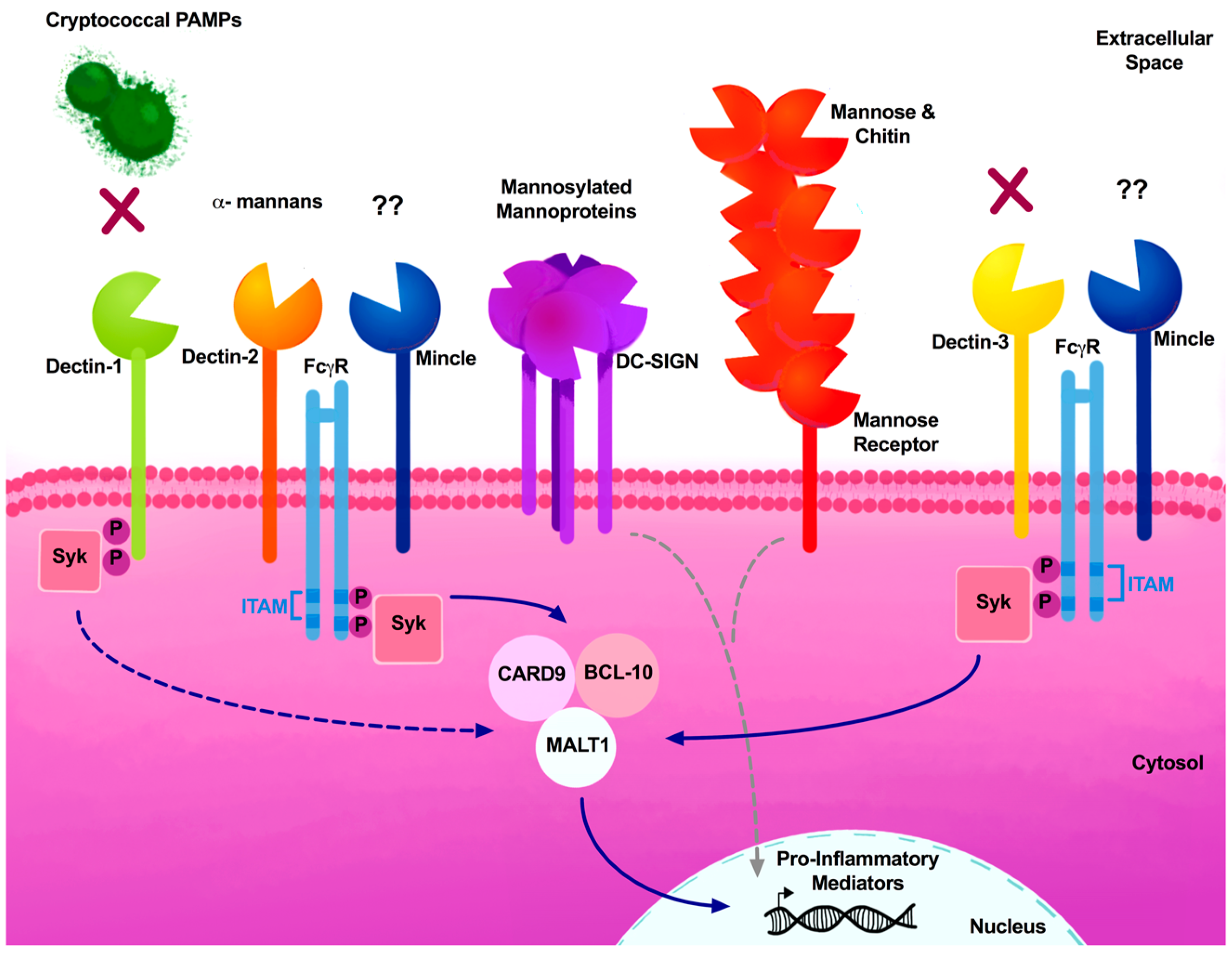

3.2. C-Type Lectin Receptors

3.3. NOD-Like Receptors (NLRs)

3.4. Other Critical Receptors

4. Cryptococcal Cell Wall PAMPs

5. Concluding Remarks

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Armstrong-James, D.; Bicanic, T.; Brown, G.D.; Hoving, J.C.; Meintjes, G.; Nielsen, K. Working Group from the, E.W.o.A.-R.M. AIDS-Related Mycoses: Current Progress in the Field and Future Priorities. Trends Microbiol. 2017, 25, 428–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon-Chung, K.J.; Fraser, J.A.; Doering, T.L.; Wang, Z.; Janbon, G.; Idnurm, A.; Bahn, Y.S. Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii, the etiologic agents of cryptococcosis. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2014, 4, a019760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perfect, J.R.; Dismukes, W.E.; Dromer, F.; Goldman, D.L.; Graybill, J.R.; Hamill, R.J.; Harrison, T.S.; Larsen, R.A.; Lortholary, O.; Nguyen, M.H.; et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of cryptococcal disease: 2010 update by the infectious diseases society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2010, 50, 291–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagen, F.; Khayhan, K.; Theelen, B.; Kolecka, A.; Polacheck, I.; Sionov, E.; Falk, R.; Parnmen, S.; Lumbsch, H.T.; Boekhout, T. Recognition of seven species in the Cryptococcus gattii/Cryptococcus neoformans species complex. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2015, 78, 16–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajasingham, R.; Smith, R.M.; Park, B.J.; Jarvis, J.N.; Govender, N.P.; Chiller, T.M.; Denning, D.W.; Loyse, A.; Boulware, D.R. Global burden of disease of HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis: An updated analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, 873–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denning, D.W. Minimizing fungal disease deaths will allow the UNAIDS target of reducing annual AIDS deaths below 500,000 by 2020 to be realized. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2016, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirofski, L.A.; Casadevall, A. Immune-Mediated Damage Completes the Parabola: Cryptococcus neoformans Pathogenesis Can Reflect the Outcome of a Weak or Strong Immune Response. mBio 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bicanic, T.; Meintjes, G.; Rebe, K.; Williams, A.; Loyse, A.; Wood, R.; Hayes, M.; Jaffar, S.; Harrison, T. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis: A prospective study. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2009, 51, 130–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neal, L.M.; Xing, E.; Xu, J.; Kolbe, J.L.; Osterholzer, J.J.; Segal, B.M.; Williamson, P.R.; Olszewski, M.A. CD4+ T Cells Orchestrate Lethal Immune Pathology despite Fungal Clearance during Cryptococcus neoformans Meningoencephalitis. mBio 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldman, D.L.; Khine, H.; Abadi, J.; Lindenberg, D.J.; Pirofski, L.; Niang, R.; Casadevall, A. Serologic evidence for Cryptococcus neoformans infection in early childhood. Pediatrics 2001, 107, E66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huffnagle, G.B.; Yates, J.L.; Lipscomb, M.F. Immunity to a pulmonary Cryptococcus neoformans infection requires both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. J. Exp. Med. 1991, 173, 793–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huffnagle, G.B. Role of cytokines in T cell immunity to a pulmonary Cryptococcus neoformans infection. Biol. Signals 1996, 5, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huffnagle, G.B.; Boyd, M.B.; Street, N.E.; Lipscomb, M.F. IL-5 is required for eosinophil recruitment, crystal deposition, and mononuclear cell recruitment during a pulmonary Cryptococcus neoformans infection in genetically susceptible mice (C57BL/6). J. Immunol. 1998, 160, 2393–2400. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Huffnagle, G.B.; Lipscomb, M.F. Cells and cytokines in pulmonary cryptococcosis. Res. Immunol. 1998, 149, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, S.A.; May, R.C. Cryptococcus interactions with macrophages: Evasion and manipulation of the phagosome by a fungal pathogen. Cell. Microbiol. 2013, 15, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osterholzer, J.J.; Surana, R.; Milam, J.E.; Montano, G.T.; Chen, G.H.; Sonstein, J.; Curtis, J.L.; Huffnagle, G.B.; Toews, G.B.; Olszewski, M.A. Cryptococcal urease promotes the accumulation of immature dendritic cells and a non-protective T2 immune response within the lung. Am. J. Pathol. 2009, 174, 932–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukaremera, L.; Nielsen, K. Adaptive Immunity to Cryptococcus neoformans Infections. J. Fungi 2017, 3, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romani, L. Immunity to fungal infections. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 11, 275–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wormley, F.L., Jr.; Perfect, J.R.; Steele, C.; Cox, G.M. Protection against cryptococcosis by using a murine γ interferon-producing Cryptococcus neoformans strain. Infect. Immun. 2007, 75, 1453–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decken, K.; Kohler, G.; Palmer-Lehmann, K.; Wunderlin, A.; Mattner, F.; Magram, J.; Gately, M.K.; Alber, G. Interleukin-12 is essential for a protective Th1 response in mice infected with Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect. Immun. 1998, 66, 4994–5000. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kawakami, K.; Koguchi, Y.; Qureshi, M.H.; Miyazato, A.; Yara, S.; Kinjo, Y.; Iwakura, Y.; Takeda, K.; Akira, S.; Kurimoto, M.; et al. IL-18 contributes to host resistance against infection with Cryptococcus neoformans in mice with defective IL-12 synthesis through induction of IFN-γ production by NK cells. J. Immunol. 2000, 165, 941–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rayhane, N.; Lortholary, O.; Fitting, C.; Callebert, J.; Huerre, M.; Dromer, F.; Cavaillon, J.M. Enhanced sensitivity of tumor necrosis factor/lymphotoxin-α-deficient mice to Cryptococcus neoformans infection despite increased levels of nitrite/nitrate, interferon-γ, and interleukin-12. J. Infect. Dis. 1999, 180, 1637–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bettelli, E.; Carrier, Y.; Gao, W.; Korn, T.; Strom, T.B.; Oukka, M.; Weiner, H.L.; Kuchroo, V.K. Reciprocal developmental pathways for the generation of pathogenic effector TH17 and regulatory T cells. Nature 2006, 441, 235–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onishi, R.M.; Gaffen, S.L. Interleukin-17 and its target genes: Mechanisms of interleukin-17 function in disease. Immunology 2010, 129, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murdock, B.J.; Teitz-Tennenbaum, S.; Chen, G.H.; Dils, A.J.; Malachowski, A.N.; Curtis, J.L.; Olszewski, M.A.; Osterholzer, J.J. Early or late IL-10 blockade enhances Th1 and Th17 effector responses and promotes fungal clearance in mice with cryptococcal lung infection. J. Immunol. 2014, 193, 4107–4116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angkasekwinai, P.; Sringkarin, N.; Supasorn, O.; Fungkrajai, M.; Wang, Y.H.; Chayakulkeeree, M.; Ngamskulrungroj, P.; Angkasekwinai, N.; Pattanapanyasat, K. Cryptococcus gattii infection dampens Th1 and Th17 responses by attenuating dendritic cell function and pulmonary chemokine expression in the immunocompetent hosts. Infect. Immun. 2014, 82, 3880–3890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szymczak, W.A.; Sellers, R.S.; Pirofski, L.A. IL-23 dampens the allergic response to Cryptococcus neoformans through IL-17-independent and -dependent mechanisms. Am. J. Pathol. 2012, 180, 1547–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wozniak, K.L.; Hardison, S.E.; Kolls, J.K.; Wormley, F.L. Role of IL-17A on resolution of pulmonary C. neoformans infection. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e17204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muller, U.; Stenzel, W.; Kohler, G.; Werner, C.; Polte, T.; Hansen, G.; Schutze, N.; Straubinger, R.K.; Blessing, M.; McKenzie, A.N.; et al. IL-13 induces disease-promoting type 2 cytokines, alternatively activated macrophages and allergic inflammation during pulmonary infection of mice with Cryptococcus neoformans. J. Immunol. 2007, 179, 5367–5377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.H.; McNamara, D.A.; Hernandez, Y.; Huffnagle, G.B.; Toews, G.B.; Olszewski, M.A. Inheritance of immune polarization patterns is linked to resistance versus susceptibility to Cryptococcus neoformans in a mouse model. Infect. Immun. 2008, 76, 2379–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, Y.; Davis, M.J.; Dayrit, J.K.; Hadd, Z.; Meister, D.L.; Osterholzer, J.J.; Williamson, P.R.; Olszewski, M.A. Immune modulation mediated by cryptococcal laccase promotes pulmonary growth and brain dissemination of virulent Cryptococcus neoformans in mice. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e47853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wozniak, K.L.; Ravi, S.; Macias, S.; Young, M.L.; Olszewski, M.A.; Steele, C.; Wormley, F.L. Insights into the mechanisms of protective immunity against Cryptococcus neoformans infection using a mouse model of pulmonary cryptococcosis. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e6854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lohmann-Matthes, M.L.; Steinmuller, C.; Franke-Ullmann, G. Pulmonary macrophages. Eur. Respir. J. 1994, 7, 1678–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McQuiston, T.J.; Williamson, P.R. Paradoxical roles of alveolar macrophages in the host response to Cryptococcus neoformans. J. Infect. Chemother. 2012, 18, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Leopold Wager, C.M.; Wormley, F.L., Jr. Classical versus alternative macrophage activation: The Ying and the Yang in host defense against pulmonary fungal infections. Mucosal Immunol. 2014, 7, 1023–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malyshev, I.; Malyshev, Y. Current Concept and Update of the Macrophage Plasticity Concept: Intracellular Mechanisms of Reprogramming and M3 Macrophage “Switch” Phenotype. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 341308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, P.J.; Wynn, T.A. Protective and pathogenic functions of macrophage subsets. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 11, 723–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rath, M.; Muller, I.; Kropf, P.; Closs, E.I.; Munder, M. Metabolism via Arginase or Nitric Oxide Synthase: Two Competing Arginine Pathways in Macrophages. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, M.J.; Tsang, T.M.; Qiu, Y.; Dayrit, J.K.; Freij, J.B.; Huffnagle, G.B.; Olszewski, M.A. Macrophage M1/M2 polarization dynamically adapts to changes in cytokine microenvironments in Cryptococcus neoformans infection. mBio 2013, 4, e00264-13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arora, S.; Olszewski, M.A.; Tsang, T.M.; McDonald, R.A.; Toews, G.B.; Huffnagle, G.B. Effect of cytokine interplay on macrophage polarization during chronic pulmonary infection with Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect. Immun. 2011, 79, 1915–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardison, S.E.; Herrera, G.; Young, M.L.; Hole, C.R.; Wozniak, K.L.; Wormley, F.L., Jr. Protective immunity against pulmonary cryptococcosis is associated with STAT1-mediated classical macrophage activation. J. Immunol. 2012, 189, 4060–4068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardison, S.E.; Ravi, S.; Wozniak, K.L.; Young, M.L.; Olszewski, M.A.; Wormley, F.L., Jr. Pulmonary infection with an interferon-γ-producing Cryptococcus neoformans strain results in classical macrophage activation and protection. Am. J. Pathol. 2010, 176, 774–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Herrero, C.; Li, W.P.; Antoniv, T.T.; Falck-Pedersen, E.; Koch, A.E.; Woods, J.M.; Haines, G.K.; Ivashkiv, L.B. Sensitization of IFN-γ Jak-STAT signaling during macrophage activation. Nat. Immunol. 2002, 3, 859–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leopold Wager, C.M.; Hole, C.R.; Wozniak, K.L.; Olszewski, M.A.; Mueller, M.; Wormley, F.L., Jr. STAT1 signaling within macrophages is required for antifungal activity against Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect. Immun. 2015, 83, 4513–4527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leopold Wager, C.M.; Hole, C.R.; Wozniak, K.L.; Olszewski, M.A.; Wormley, F.L., Jr. STAT1 signaling is essential for protection against Cryptococcus neoformans infection in mice. J. Immunol. 2014, 193, 4060–4071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardison, S.E.; Wozniak, K.L.; Kolls, J.K.; Wormley, F.L., Jr. Interleukin-17 is not required for classical macrophage activation in a pulmonary mouse model of Cryptococcus neoformans infection. Infect. Immun. 2010, 78, 5341–5351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eastman, A.J.; He, X.; Qiu, Y.; Davis, M.J.; Vedula, P.; Lyons, D.M.; Park, Y.D.; Hardison, S.E.; Malachowski, A.N.; Osterholzer, J.J.; et al. Cryptococcal heat shock protein 70 homolog Ssa1 contributes to pulmonary expansion of Cryptococcus neoformans during the afferent phase of the immune response by promoting macrophage M2 polarization. J. Immunol. 2015, 194, 5999–6010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syme, R.M.; Spurrell, J.C.; Amankwah, E.K.; Green, F.H.; Mody, C.H. Primary dendritic cells phagocytose Cryptococcus neoformans via mannose receptors and Fcγ receptor II for presentation to T lymphocytes. Infect. Immun. 2002, 70, 5972–5981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, R.M.; Chen, J.; Yauch, L.E.; Levitz, S.M. Opsonic requirements for dendritic cell-mediated responses to Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect. Immun. 2005, 73, 592–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wozniak, K.L.; Vyas, J.M.; Levitz, S.M. In vivo role of dendritic cells in a murine model of pulmonary cryptococcosis. Infect. Immun. 2006, 74, 3817–3824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wozniak, K.L.; Levitz, S.M. Cryptococcus neoformans enters the endolysosomal pathway of dendritic cells and is killed by lysosomal components. Infect. Immun. 2008, 76, 4764–4771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hole, C.R.; Bui, H.; Wormley, F.L., Jr.; Wozniak, K.L. Mechanisms of dendritic cell lysosomal killing of Cryptococcus. Sci. Rep. 2012, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syme, R.M.; Spurrell, J.C.; Ma, L.L.; Green, F.H.; Mody, C.H. Phagocytosis and protein processing are required for presentation of Cryptococcus neoformans mitogen to T lymphocytes. Infect. Immun. 2000, 68, 6147–6153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauman, S.K.; Nichols, K.L.; Murphy, J.W. Dendritic cells in the induction of protective and nonprotective anticryptococcal cell-mediated immune responses. J. Immunol. 2000, 165, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieira, P.L.; de Jong, E.C.; Wierenga, E.A.; Kapsenberg, M.L.; Kalinski, P. Development of Th1-inducing capacity in myeloid dendritic cells requires environmental instruction. J. Immunol. 2000, 164, 4507–4512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osterholzer, J.J.; Milam, J.E.; Chen, G.H.; Toews, G.B.; Huffnagle, G.B.; Olszewski, M.A. Role of dendritic cells and alveolar macrophages in regulating early host defense against pulmonary infection with Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect. Immun. 2009, 77, 3749–3758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Eastman, A.J.; Flaczyk, A.; Neal, L.M.; Zhao, G.; Carolan, J.; Malachowski, A.N.; Stolberg, V.R.; Yosri, M.; Chensue, S.W.; et al. Disruption of Early Tumor Necrosis Factor α Signaling Prevents Classical Activation of Dendritic Cells in Lung-Associated Lymph Nodes and Development of Protective Immunity against Cryptococcal Infection. mBio 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huston, S.M.; Li, S.S.; Stack, D.; Timm-McCann, M.; Jones, G.J.; Islam, A.; Berenger, B.M.; Xiang, R.F.; Colarusso, P.; Mody, C.H. Cryptococcus gattii is killed by dendritic cells, but evades adaptive immunity by failing to induce dendritic cell maturation. J. Immunol. 2013, 191, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiller, T.; Farrokhshad, K.; Brummer, E.; Stevens, D.A. Effect of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor on polymorphonuclear neutrophils, monocytes or monocyte-derived macrophages combined with voriconazole against Cryptococcus neoformans. Med. Mycol. 2002, 40, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, D.; Zhang, M.; Liu, G.; Wu, H.; Zhu, X.; Zhou, H.; Shi, M. Real-Time Imaging of Interactions of Neutrophils with Cryptococcus neoformans Demonstrates a Crucial Role of Complement C5a-C5aR Signaling. Infect. Immun. 2015, 84, 216–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, D.; Shi, M. Neutrophil swarming toward Cryptococcus neoformans is mediated by complement and leukotriene B4. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2016, 477, 945–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Z.M.; Murphy, J.W. Mobility of human neutrophils in response to Cryptococcus neoformans cells, culture filtrate antigen, and individual components of the antigen. Infect. Immun. 1993, 61, 5067–5077. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dong, Z.M.; Murphy, J.W. Intravascular cryptococcal culture filtrate (CneF) and its major component, glucuronoxylomannan, are potent inhibitors of leukocyte accumulation. Infect. Immun. 1995, 63, 770–778. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ellerbroek, P.M.; Ulfman, L.H.; Hoepelman, A.I.; Coenjaerts, F.E. Cryptococcal glucuronoxylomannan interferes with neutrophil rolling on the endothelium. Cell. Microbiol. 2004, 6, 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.Y.; Thompson, G.R., III; Hastey, C.J.; Hodge, G.C.; Lunetta, J.M.; Pappagianis, D.; Heinrich, V. Coccidioides Endospores and Spherules Draw Strong Chemotactic, Adhesive, and Phagocytic Responses by Individual Human Neutrophils. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0129522. [Google Scholar]

- Ellerbroek, P.M.; Lefeber, D.J.; van Veghel, R.; Scharringa, J.; Brouwer, E.; Gerwig, G.J.; Janbon, G.; Hoepelman, A.I.; Coenjaerts, F.E. O-acetylation of cryptococcal capsular glucuronoxylomannan is essential for interference with neutrophil migration. J. Immunol. 2004, 173, 7513–7520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha, J.D.; Nascimento, M.T.; Decote-Ricardo, D.; Corte-Real, S.; Morrot, A.; Heise, N.; Nunes, M.P.; Previato, J.O.; Mendonca-Previato, L.; DosReis, G.A.; et al. Capsular polysaccharides from Cryptococcus neoformans modulate production of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) by human neutrophils. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mambula, S.S.; Simons, E.R.; Hastey, R.; Selsted, M.E.; Levitz, S.M. Human neutrophil-mediated nonoxidative antifungal activity against Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect. Immun. 2000, 68, 6257–6264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mednick, A.J.; Feldmesser, M.; Rivera, J.; Casadevall, A. Neutropenia alters lung cytokine production in mice and reduces their susceptibility to pulmonary cryptococcosis. Eur. J. Immunol. 2003, 33, 1744–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wozniak, K.L.; Kolls, J.K.; Wormley, F.L., Jr. Depletion of neutrophils in a protective model of pulmonary cryptococcosis results in increased IL-17A production by γδ T cells. BMC Immunol. 2012, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feretzaki, M.; Hardison, S.E.; Wormley, F.L., Jr.; Heitman, J. Cryptococcus neoformans hyperfilamentous strain is hypervirulent in a murine model of cryptococcal meningoencephalitis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e104432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Meara, T.R.; Holmer, S.M.; Selvig, K.; Dietrich, F.; Alspaugh, J.A. Cryptococcus neoformans Rim101 is associated with cell wall remodeling and evasion of the host immune responses. mBio 2013, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiesner, D.L.; Smith, K.D.; Kashem, S.W.; Bohjanen, P.R.; Nielsen, K. Different Lymphocyte Populations Direct Dichotomous Eosinophil or Neutrophil Responses to Pulmonary Cryptococcus Infection. J. Immunol. 2017, 198, 1627–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, J.A. The immune response of Drosophila. Nature 2003, 426, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akira, S.; Uematsu, S.; Takeuchi, O. Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell 2006, 124, 783–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawai, T.; Takeuchi, O.; Fujita, T.; Inoue, J.; Muhlradt, P.F.; Sato, S.; Hoshino, K.; Akira, S. Lipopolysaccharide stimulates the MyD88-independent pathway and results in activation of IFN-regulatory factor 3 and the expression of a subset of lipopolysaccharide-inducible genes. J. Immunol. 2001, 167, 5887–5894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arthur, J.S.; Ley, S.C. Mitogen-activated protein kinases in innate immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2013, 13, 679–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Mahony, D.S.; Pham, U.; Iyer, R.; Hawn, T.R.; Liles, W.C. Differential constitutive and cytokine-modulated expression of human Toll-like receptors in primary neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2008, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viriyakosol, S.; Fierer, J.; Brown, G.D.; Kirkland, T.N. Innate immunity to the pathogenic fungus Coccidioides posadasii is dependent on Toll-like receptor 2 and Dectin-1. Infect. Immun. 2005, 73, 1553–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Netea, M.G.; Ferwerda, G.; van der Graaf, C.A.; Van der Meer, J.W.; Kullberg, B.J. Recognition of fungal pathogens by toll-like receptors. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2006, 12, 4195–4201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorgi, C.A.; Secatto, A.; Fontanari, C.; Turato, W.M.; Belanger, C.; de Medeiros, A.I.; Kashima, S.; Marleau, S.; Covas, D.T.; Bozza, P.T.; et al. Histoplasma capsulatum cell wall β-glucan induces lipid body formation through CD18, TLR2, and dectin-1 receptors: Correlation with leukotriene B4 generation and role in HIV-1 infection. J. Immunol. 2009, 182, 4025–4035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yauch, L.E.; Mansour, M.K.; Shoham, S.; Rottman, J.B.; Levitz, S.M. Involvement of CD14, toll-like receptors 2 and 4, and MyD88 in the host response to the fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans in vivo. Infect. Immun. 2004, 72, 5373–5382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biondo, C.; Midiri, A.; Messina, L.; Tomasello, F.; Garufi, G.; Catania, M.R.; Bombaci, M.; Beninati, C.; Teti, G.; Mancuso, G. MyD88 and TLR2, but not TLR4, are required for host defense against Cryptococcus neoformans. Eur. J. Immunol. 2005, 35, 870–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, K.; Miyagi, K.; Koguchi, Y.; Kinjo, Y.; Uezu, K.; Kinjo, T.; Akamine, M.; Fujita, J.; Kawamura, I.; Mitsuyama, M.; et al. Limited contribution of Toll-like receptor 2 and 4 to the host response to a fungal infectious pathogen, Cryptococcus neoformans. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2006, 47, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yauch, L.E.; Mansour, M.K.; Levitz, S.M. Receptor-mediated clearance of Cryptococcus neoformans capsular polysaccharide in vivo. Infect. Immun. 2005, 73, 8429–8432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonseca, F.L.; Nohara, L.L.; Cordero, R.J.; Frases, S.; Casadevall, A.; Almeida, I.C.; Nimrichter, L.; Rodrigues, M.L. Immunomodulatory effects of serotype B glucuronoxylomannan from Cryptococcus gattii correlate with polysaccharide diameter. Infect. Immun. 2010, 78, 3861–3870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoham, S.; Huang, C.; Chen, J.M.; Golenbock, D.T.; Levitz, S.M. Toll-like receptor 4 mediates intracellular signaling without TNF-α release in response to Cryptococcus neoformans polysaccharide capsule. J. Immunol. 2001, 166, 4620–4626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, K.; Miyazato, A.; Xiao, G.; Hatta, M.; Inden, K.; Aoyagi, T.; Shiratori, K.; Takeda, K.; Akira, S.; Saijo, S.; et al. Deoxynucleic acids from Cryptococcus neoformans activate myeloid dendritic cells via a TLR9-dependent pathway. J. Immunol. 2008, 180, 4067–4074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, Y.; Zeltzer, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, F.; Chen, G.H.; Dayrit, J.; Murdock, B.J.; Bhan, U.; Toews, G.B.; Osterholzer, J.J.; et al. Early induction of CCL7 downstream of TLR9 signaling promotes the development of robust immunity to Cryptococcal infection. J. Immunol. 2012, 188, 3940–3948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, K.; Kinjo, T.; Saijo, S.; Miyazato, A.; Adachi, Y.; Ohno, N.; Fujita, J.; Kaku, M.; Iwakura, Y.; Kawakami, K. Dectin-1 is not required for the host defense to Cryptococcus neoformans. Microbiol. Immunol. 2007, 51, 1115–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, N.M.; Wuthrich, M.; Wang, H.; Klein, B.; Hull, C.M. Characterization of C-type lectins reveals an unexpectedly limited interaction between Cryptococcus neoformans spores and Dectin-1. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0173866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, Y.; Sato, K.; Yamamoto, H.; Matsumura, K.; Matsumoto, I.; Nomura, T.; Miyasaka, T.; Ishii, K.; Kanno, E.; Tachi, M.; et al. Dectin-2 deficiency promotes Th2 response and mucin production in the lungs after pulmonary infection with Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect. Immun. 2015, 83, 671–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishikawa, T.; Itoh, F.; Yoshida, S.; Saijo, S.; Matsuzawa, T.; Gonoi, T.; Saito, T.; Okawa, Y.; Shibata, N.; Miyamoto, T.; et al. Identification of distinct ligands for the C-type lectin receptors Mincle and Dectin-2 in the pathogenic fungus Malassezia. Cell Host Microbe 2013, 13, 477–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hole, C.R.; Leopold Wager, C.M.; Mendiola, A.S.; Wozniak, K.L.; Campuzano, A.; Lin, X.; Wormley, F.L., Jr. Antifungal Activity of Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells against Cryptococcus neoformans In Vitro Requires Expression of Dectin-3 (CLEC4D) and Reactive Oxygen Species. Infect. Immun. 2016, 84, 2493–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campuzano, A.; Castro-Lopez, N.; Wozniak, K.L.; Leopold Wager, C.M.; Wormley, F.L., Jr. Dectin-3 Is Not Required for Protection against Cryptococcus neoformans Infection. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0169347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamasaki, S.; Matsumoto, M.; Takeuchi, O.; Matsuzawa, T.; Ishikawa, E.; Sakuma, M.; Tateno, H.; Uno, J.; Hirabayashi, J.; Mikami, Y.; et al. C-type lectin Mincle is an activating receptor for pathogenic fungus, Malassezia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 1897–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dan, J.M.; Kelly, R.M.; Lee, C.K.; Levitz, S.M. Role of the mannose receptor in a murine model of Cryptococcus neoformans infection. Infect. Immun. 2008, 76, 2362–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansour, M.K.; Latz, E.; Levitz, S.M. Cryptococcus neoformans glycoantigens are captured by multiple lectin receptors and presented by dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 2006, 176, 3053–3061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, C.; Chen, M.; Fa, Z.; Lu, A.; Fang, W.; Sun, B.; Chen, C.; Liao, W.; Meng, G. Acapsular Cryptococcus neoformans activates the NLRP3 inflammasome. Microbes Infect. 2014, 16, 845–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Xing, Y.; Lu, A.; Fang, W.; Sun, B.; Chen, C.; Liao, W.; Meng, G. Internalized Cryptococcus neoformans Activates the Canonical Caspase-1 and the Noncanonical Caspase-8 Inflammasomes. J. Immunol. 2015, 195, 4962–4972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redlich, S.; Ribes, S.; Schutze, S.; Eiffert, H.; Nau, R. Toll-like receptor stimulation increases phagocytosis of Cryptococcus neoformans by microglial cells. J. Neuroinflamm. 2013, 10, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez-Ortiz, Z.G.; Specht, C.A.; Wang, J.P.; Lee, C.K.; Bartholomeu, D.C.; Gazzinelli, R.T.; Levitz, S.M. Toll-like receptor 9-dependent immune activation by unmethylated CpG motifs in Aspergillus fumigatus DNA. Infect. Immun. 2008, 76, 2123–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biondo, C.; Signorino, G.; Costa, A.; Midiri, A.; Gerace, E.; Galbo, R.; Bellantoni, A.; Malara, A.; Beninati, C.; Teti, G.; et al. Recognition of yeast nucleic acids triggers a host-protective type I interferon response. Eur. J. Immunol. 2011, 41, 1969–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyazato, A.; Nakamura, K.; Yamamoto, N.; Mora-Montes, H.M.; Tanaka, M.; Abe, Y.; Tanno, D.; Inden, K.; Gang, X.; Ishii, K.; et al. Toll-like receptor 9-dependent activation of myeloid dendritic cells by Deoxynucleic acids from Candida albicans. Infect. Immun. 2009, 77, 3056–3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, N.S.; Kasperkovitz, P.V.; Timmons, A.K.; Mansour, M.K.; Tam, J.M.; Seward, M.W.; Reedy, J.L.; Puranam, S.; Feliu, M.; Vyas, J.M. Dectin-1 Controls TLR9 Trafficking to Phagosomes Containing β-1,3 Glucan. J. Immunol. 2016, 196, 2249–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villamon, E.; Gozalbo, D.; Roig, P.; Murciano, C.; O’Connor, J.E.; Fradelizi, D.; Gil, M.L. Myeloid differentiation factor 88 (MyD88) is required for murine resistance to Candida albicans and is critically involved in Candida -induced production of cytokines. Eur. Cytokine Netw. 2004, 15, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bellocchio, S.; Montagnoli, C.; Bozza, S.; Gaziano, R.; Rossi, G.; Mambula, S.S.; Vecchi, A.; Mantovani, A.; Levitz, S.M.; Romani, L. The contribution of the Toll-like/IL-1 receptor superfamily to innate and adaptive immunity to fungal pathogens in vivo. J. Immunol. 2004, 172, 3059–3069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, C.Y.; Castro-Lopez, N.; Cole, G.T. CARD9- and MyD88-mediated IFN-γ and Nitric Oxide Productions Are Essential for Resistance to Subcutaneous Coccidioides Infection. Infect. Immun. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loures, F.V.; Pina, A.; Felonato, M.; Feriotti, C.; de Araujo, E.F.; Calich, V.L. MyD88 signaling is required for efficient innate and adaptive immune responses to Paracoccidioides brasiliensis infection. Infect. Immun. 2011, 79, 2470–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Bernuth, H.; Picard, C.; Puel, A.; Casanova, J.L. Experimental and natural infections in MyD88- and IRAK-4-deficient mice and humans. Eur. J. Immunol. 2012, 42, 3126–3135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Bernuth, H.; Picard, C.; Jin, Z.; Pankla, R.; Xiao, H.; Ku, C.L.; Chrabieh, M.; Mustapha, I.B.; Ghandil, P.; Camcioglu, Y.; et al. Pyogenic bacterial infections in humans with MyD88 deficiency. Science 2008, 321, 691–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoving, J.C.; Wilson, G.J.; Brown, G.D. Signalling C-type lectin receptors, microbial recognition and immunity. Cell. Microbiol. 2014, 16, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plato, A.; Willment, J.A.; Brown, G.D. C-type lectin-like receptors of the Dectin-1 cluster: Ligands and signaling pathways. Int. Rev. Immunol. 2013, 32, 134–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth, S.; Bergmann, H.; Jaeger, M.; Yeroslaviz, A.; Neumann, K.; Koenig, P.A.; Prazeres da Costa, C.; Vanes, L.; Kumar, V.; Johnson, M.; et al. Vav Proteins Are Key Regulators of CARD9 Signaling for Innate Antifungal Immunity. Cell Rep. 2016, 17, 2572–2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodridge, H.S.; Shimada, T.; Wolf, A.J.; Hsu, Y.M.; Becker, C.A.; Lin, X.; Underhill, D.M. Differential use of CARD9 by Dectin-1 in macrophages and dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 2009, 182, 1146–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strasser, D.; Neumann, K.; Bergmann, H.; Marakalala, M.J.; Guler, R.; Rojowska, A.; Hopfner, K.P.; Brombacher, F.; Urlaub, H.; Baier, G.; et al. Syk kinase-coupled C-type lectin receptors engage protein kinase C-sigma to elicit CARD9 adaptor-mediated innate immunity. Immunity 2012, 36, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamasaki, S.; Ishikawa, E.; Sakuma, M.; Hara, H.; Ogata, K.; Saito, T. Mincle is an ITAM-coupled activating receptor that senses damaged cells. Nat. Immunol. 2008, 9, 1179–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gringhuis, S.I.; den Dunnen, J.; Litjens, M.; van der Vlist, M.; Wevers, B.; Bruijns, S.C.; Geijtenbeek, T.B. Dectin-1 directs T helper cell differentiation by controlling noncanonical NF-kappaB activation through Raf-1 and Syk. Nat. Immunol. 2009, 10, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, J.B.; Sircy, L.M.; Heusinkveld, L.E.; Ding, W.; Leander, R.N.; McClelland, E.E.; Nelson, D.E. Modulation of Macrophage Inflammatory Nuclear Factor kappaB (NF-kappaB) Signaling by Intracellular Cryptococcus neoformans. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 15614–15627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobato-Pascual, A.; Saether, P.C.; Fossum, S.; Dissen, E.; Daws, M.R. Mincle, the receptor for mycobacterial cord factor, forms a functional receptor complex with MCL and Fc epsilon RI-γ. Eur. J. Immunol. 2013, 43, 3167–3174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyake, Y.; Toyonaga, K.; Mori, D.; Kakuta, S.; Hoshino, Y.; Oyamada, A.; Yamada, H.; Ono, K.; Suyama, M.; Iwakura, Y.; et al. C-type lectin MCL is an FcRγ-coupled receptor that mediates the adjuvanticity of mycobacterial cord factor. Immunity 2013, 38, 1050–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, L.M.; Gupta, V.; Schafer, G.; Reid, D.M.; Kimberg, M.; Dennehy, K.M.; Hornsell, W.G.; Guler, R.; Campanero-Rhodes, M.A.; Palma, A.S.; et al. The C-type lectin receptor CLECSF8 (CLEC4D) is expressed by myeloid cells and triggers cellular activation through Syk kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 25964–25974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, L.L.; Zhao, X.Q.; Jiang, C.; You, Y.; Chen, X.P.; Jiang, Y.Y.; Jia, X.M.; Lin, X. C-type lectin receptors Dectin-3 and Dectin-2 form a heterodimeric pattern-recognition receptor for host defense against fungal infection. Immunity 2013, 39, 324–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodridge, H.S.; Simmons, R.M.; Underhill, D.M. Dectin-1 stimulation by Candida albicans yeast or zymosan triggers NFAT activation in macrophages and dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 2007, 178, 3107–3115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, G.D.; Gordon, S. Immune recognition. A new receptor for β-glucans. Nature 2001, 413, 36–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ariizumi, K.; Shen, G.L.; Shikano, S.; Xu, S.; Ritter, R., 3rd.; Kumamoto, T.; Edelbaum, D.; Morita, A.; Bergstresser, P.R.; Takashima, A. Identification of a novel, dendritic cell-associated molecule, Dectin-1, by subtractive cDNA cloning. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 20157–20167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steele, C.; Rapaka, R.R.; Metz, A.; Pop, S.M.; Williams, D.L.; Gordon, S.; Kolls, J.K.; Brown, G.D. The β-glucan receptor dectin-1 recognizes specific morphologies of Aspergillus fumigatus. PLoS Pathog. 2005, 1, e42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gow, N.A.; Netea, M.G.; Munro, C.A.; Ferwerda, G.; Bates, S.; Mora-Montes, H.M.; Walker, L.; Jansen, T.; Jacobs, L.; Tsoni, V.; et al. Immune recognition of Candida albicans β-glucan by Dectin-1. J. Infect. Dis. 2007, 196, 1565–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, K.; Miyazato, A.; Koguchi, Y.; Adachi, Y.; Ohno, N.; Saijo, S.; Iwakura, Y.; Takeda, K.; Akira, S.; Fujita, J.; et al. Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) and Dectin-1 contribute to the production of IL-12p40 by bone marrow-derived dendritic cells infected with Penicillium marneffei. Microbes Infect. 2008, 10, 1223–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubino, I.; Coste, A.; Le Roy, D.; Roger, T.; Jaton, K.; Boeckh, M.; Monod, M.; Latge, J.P.; Calandra, T.; Bochud, P.Y. Species-specific recognition of Aspergillus fumigatus by Toll-like receptor 1 and Toll-like receptor 6. J. Infect. Dis. 2012, 205, 944–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, P.R.; Tsoni, S.V.; Willment, J.A.; Dennehy, K.M.; Rosas, M.; Findon, H.; Haynes, K.; Steele, C.; Botto, M.; Gordon, S.; et al. Dectin-1 is required for β-glucan recognition and control of fungal infection. Nat. Immunol. 2007, 8, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giles, S.S.; Dagenais, T.R.; Botts, M.R.; Keller, N.P.; Hull, C.M. Elucidating the pathogenesis of spores from the human fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect. Immun. 2009, 77, 3491–3500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ifrim, D.C.; Bain, J.M.; Reid, D.M.; Oosting, M.; Verschueren, I.; Gow, N.A.; van Krieken, J.H.; Brown, G.D.; Kullberg, B.J.; Joosten, L.A.; et al. Role of Dectin-2 for host defense against systemic infection with Candida glabrata. Infect. Immun. 2014, 82, 1064–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, M.J.; Osorio, F.; Rosas, M.; Freitas, R.P.; Schweighoffer, E.; Gross, O.; Verbeek, J.S.; Ruland, J.; Tybulewicz, V.; Brown, G.D.; et al. Dectin-2 is a Syk-coupled pattern recognition receptor crucial for Th17 responses to fungal infection. J. Exp. Med. 2009, 206, 2037–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loures, F.V.; Rohm, M.; Lee, C.K.; Santos, E.; Wang, J.P.; Specht, C.A.; Calich, V.L.; Urban, C.F.; Levitz, S.M. Recognition of Aspergillus fumigatus hyphae by human plasmacytoid dendritic cells is mediated by Dectin-2 and results in formation of extracellular traps. PLoS Pathog. 2015, 11, e1004643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Xu, X.Y.; Shao, H.T.; Su, X.; Wu, X.D.; Wang, Q.; Shi, Y. Dectin-2 is predominately macrophage restricted and exhibits conspicuous expression during Aspergillus fumigatus invasion in human lung. Cell. Immunol. 2013, 284, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGreal, E.P.; Rosas, M.; Brown, G.D.; Zamze, S.; Wong, S.Y.; Gordon, S.; Martinez-Pomares, L.; Taylor, P.R. The carbohydrate-recognition domain of Dectin-2 is a C-type lectin with specificity for high mannose. Glycobiology 2006, 16, 422–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, K.; Yang, X.L.; Yudate, T.; Chung, J.S.; Wu, J.; Luby-Phelps, K.; Kimberly, R.P.; Underhill, D.; Cruz, P.D., Jr.; Ariizumi, K. Dectin-2 is a pattern recognition receptor for fungi that couples with the Fc receptor γ chain to induce innate immune responses. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 38854–38866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balch, S.G.; McKnight, A.J.; Seldin, M.F.; Gordon, S. Cloning of a novel C-type lectin expressed by murine macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 18656–18664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arce, I.; Martinez-Munoz, L.; Roda-Navarro, P.; Fernandez-Ruiz, E. The human C-type lectin CLECSF8 is a novel monocyte/macrophage endocytic receptor. Eur. J. Immunol. 2004, 34, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, M.; Tanaka, T.; Kaisho, T.; Sanjo, H.; Copeland, N.G.; Gilbert, D.J.; Jenkins, N.A.; Akira, S. A novel LPS-inducible C-type lectin is a transcriptional target of NF-IL6 in macrophages. J. Immunol. 1999, 163, 5039–5048. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Miyake, Y.; Masatsugu, O.H.; Yamasaki, S. C-Type Lectin Receptor MCL Facilitates Mincle Expression and Signaling through Complex Formation. J. Immunol. 2015, 194, 5366–5374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marodi, L.; Korchak, H.M.; Johnston, R.B., Jr. Mechanisms of host defense against Candida species. I. Phagocytosis by monocytes and monocyte-derived macrophages. J. Immunol. 1991, 146, 2783–2789. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ezekowitz, R.A.; Williams, D.J.; Koziel, H.; Armstrong, M.Y.; Warner, A.; Richards, F.F.; Rose, R.M. Uptake of Pneumocystis carinii mediated by the macrophage mannose receptor. Nature 1991, 351, 155–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietrella, D.; Corbucci, C.; Perito, S.; Bistoni, G.; Vecchiarelli, A. Mannoproteins from Cryptococcus neoformans promote dendritic cell maturation and activation. Infect. Immun. 2005, 73, 820–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dan, J.M.; Wang, J.P.; Lee, C.K.; Levitz, S.M. Cooperative stimulation of dendritic cells by Cryptococcus neoformans mannoproteins and CpG oligodeoxynucleotides. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinsbroek, S.E.; Taylor, P.R.; Martinez, F.O.; Martinez-Pomares, L.; Brown, G.D.; Gordon, S. Stage-specific sampling by pattern recognition receptors during Candida albicans phagocytosis. PLoS Pathog. 2008, 4, e1000218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagener, J.; Malireddi, R.K.; Lenardon, M.D.; Koberle, M.; Vautier, S.; MacCallum, D.M.; Biedermann, T.; Schaller, M.; Netea, M.G.; Kanneganti, T.D.; et al. Fungal chitin dampens inflammation through IL-10 induction mediated by NOD2 and TLR9 activation. PLoS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1004050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Kooyk, Y.; Geijtenbeek, T.B. DC-SIGN: Escape mechanism for pathogens. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2003, 3, 697–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engering, A.; Van Vliet, S.J.; Geijtenbeek, T.B.; Van Kooyk, Y. Subset of DC-SIGN(+) dendritic cells in human blood transmits HIV-1 to T lymphocytes. Blood 2002, 100, 1780–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engering, A.; Geijtenbeek, T.B.; van Vliet, S.J.; Wijers, M.; van Liempt, E.; Demaurex, N.; Lanzavecchia, A.; Fransen, J.; Figdor, C.G.; Piguet, V.; et al. The dendritic cell-specific adhesion receptor DC-SIGN internalizes antigen for presentation to T cells. J. Immunol. 2002, 168, 2118–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serrano-Gomez, D.; Leal, J.A.; Corbi, A.L. DC-SIGN mediates the binding of Aspergillus fumigatus and keratinophylic fungi by human dendritic cells. Immunobiology 2005, 210, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sainz, J.; Lupianez, C.B.; Segura-Catena, J.; Vazquez, L.; Rios, R.; Oyonarte, S.; Hemminki, K.; Forsti, A.; Jurado, M. Dectin-1 and DC-SIGN polymorphisms associated with invasive pulmonary Aspergillosis infection. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e32273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saijo, S.; Ikeda, S.; Yamabe, K.; Kakuta, S.; Ishigame, H.; Akitsu, A.; Fujikado, N.; Kusaka, T.; Kubo, S.; Chung, S.H.; et al. Dectin-2 recognition of α-mannans and induction of Th17 cell differentiation is essential for host defense against Candida albicans. Immunity 2010, 32, 681–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glocker, E.O.; Hennigs, A.; Nabavi, M.; Schaffer, A.A.; Woellner, C.; Salzer, U.; Pfeifer, D.; Veelken, H.; Warnatz, K.; Tahami, F.; et al. A homozygous CARD9 mutation in a family with susceptibility to fungal infections. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 361, 1727–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drummond, R.A.; Lionakis, M.S. Mechanistic Insights into the Role of C-Type Lectin Receptor/CARD9 Signaling in Human Antifungal Immunity. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2016, 6, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cetinkaya, P.G.; Ayvaz, D.C.; Karaatmaca, B.; Gocmen, R.; Soylemezoglu, F.; Bainter, W.; Chou, J.; Chatila, T.A.; Tezcan, I. A young girl with severe cerebral fungal infection due to CARD9 deficiency. Clin. Immunol. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, H.; Nakamura, Y.; Sato, K.; Takahashi, Y.; Nomura, T.; Miyasaka, T.; Ishii, K.; Hara, H.; Yamamoto, N.; Kanno, E.; et al. Defect of CARD9 leads to impaired accumulation of γ interferon-producing memory phenotype T cells in lungs and increased susceptibility to pulmonary infection with Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect. Immun. 2014, 82, 1606–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Vinh, D.C.; Casanova, J.L.; Puel, A. Inborn errors of immunity underlying fungal diseases in otherwise healthy individuals. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2017, 40, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.K.; Shin, J.S.; Nahm, M.H. NOD-Like Receptors in Infection, Immunity, and Diseases. Yonsei Med. J. 2016, 57, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franchi, L.; Munoz-Planillo, R.; Nunez, G. Sensing and reacting to microbes through the inflammasomes. Nat. Immunol. 2012, 13, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaki, M.H.; Boyd, K.L.; Vogel, P.; Kastan, M.B.; Lamkanfi, M.; Kanneganti, T.D. The NLRP3 inflammasome protects against loss of epithelial integrity and mortality during experimental colitis. Immunity 2010, 32, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, R.F., Jr.; Thakur, S.A.; Mayfair, J.K.; Holian, A. MARCO mediates silica uptake and toxicity in alveolar macrophages from C57BL/6 mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 34218–34226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Flaczyk, A.; Neal, L.M.; Fa, Z.; Eastman, A.J.; Malachowski, A.N.; Cheng, D.; Moore, B.B.; Curtis, J.L.; Osterholzer, J.J.; et al. Scavenger Receptor MARCO Orchestrates Early Defenses and Contributes to Fungal Containment during Cryptococcal Infection. J. Immunol. 2017, 198, 3548–3557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Flaczyk, A.; Neal, L.M.; Fa, Z.; Cheng, D.; Ivey, M.; Moore, B.B.; Curtis, J.L.; Osterholzer, J.J.; Olszewski, M.A. Exploitation of Scavenger Receptor, Macrophage Receptor with Collagenous Structure, by Cryptococcus neoformans Promotes Alternative Activation of Pulmonary Lymph Node CD11b(+) Conventional Dendritic Cells and Non-Protective Th2 Bias. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voelz, K.; May, R.C. Cryptococcal interactions with the host immune system. Eukaryot. Cell 2010, 9, 835–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaragoza, O.; Taborda, C.P.; Casadevall, A. The efficacy of complement-mediated phagocytosis of Cryptococcus neoformans is dependent on the location of C3 in the polysaccharide capsule and involves both direct and indirect C3-mediated interactions. Eur. J. Immunol. 2003, 33, 1957–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, V.; Del Poeta, M. Role of glucose in the expression of Cryptococcus neoformans antiphagocytic protein 1, App1. Eukaryot. Cell 2011, 10, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mershon, K.L.; Vasuthasawat, A.; Lawson, G.W.; Morrison, S.L.; Beenhouwer, D.O. Role of complement in protection against Cryptococcus gattii infection. Infect. Immun. 2009, 77, 1061–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urai, M.; Kaneko, Y.; Ueno, K.; Okubo, Y.; Aizawa, T.; Fukazawa, H.; Sugita, T.; Ohno, H.; Shibuya, K.; Kinjo, Y.; et al. Evasion of Innate Immune Responses by the Highly Virulent Cryptococcus gattii by Altering Capsule Glucuronoxylomannan Structure. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2015, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, F.; Wolf, J.M.; da Silva, T.A.; DeLeon-Rodriguez, C.M.; Rezende, C.P.; Pessoni, A.M.; Fernandes, F.F.; Silva-Rocha, R.; Martinez, R.; Rodrigues, M.L.; et al. Galectin-3 impacts Cryptococcus neoformans infection through direct antifungal effects. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, L.; Wolf, J.M.; Prados-Rosales, R.; Casadevall, A. Through the wall: Extracellular vesicles in Gram-positive bacteria, mycobacteria and fungi. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 13, 620–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alspaugh, J.A. Virulence mechanisms and Cryptococcus neoformans pathogenesis. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2015, 78, 55–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doering, T.L. How does Cryptococcus get its coat? Trends Microbiol. 2000, 8, 547–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reese, A.J.; Doering, T.L. Cell wall α-1,3-glucan is required to anchor the Cryptococcus neoformans capsule. Mol. Microbiol. 2003, 50, 1401–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snarr, B.D.; Qureshi, S.T.; Sheppard, D.C. Immune Recognition of Fungal Polysaccharides. J. Fungi 2017, 3, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doering, T.L. How sweet it is! Cell wall biogenesis and polysaccharide capsule formation in Cryptococcus neoformans. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2009, 63, 223–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, M.L.; Nakayasu, E.S.; Oliveira, D.L.; Nimrichter, L.; Nosanchuk, J.D.; Almeida, I.C.; Casadevall, A. Extracellular vesicles produced by Cryptococcus neoformans contain protein components associated with virulence. Eukaryot. Cell 2008, 7, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stappers, M.H.T.; Clark, A.E.; Aimanianda, V.; Bidula, S.; Reid, D.M.; Asamaphan, P.; Hardison, S.E.; Dambuza, I.M.; Valsecchi, I.; Kerscher, B.; et al. Recognition of DHN-melanin by a C-type lectin receptor is required for immunity to Aspergillus. Nature 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ost, K.S.; Esher, S.K.; Leopold Wager, C.M.; Walker, L.; Wagener, J.; Munro, C.; Wormley, F.L., Jr.; Alspaugh, J.A. Rim Pathway-Mediated Alterations in the Fungal Cell Wall Influence Immune Recognition and Inflammation. mBio 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| PRRs | PAMP | Model System | Outcome | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TLR2 | GXM | TLR2 KO (C57B1/6) | TLR2 KO mice were more susceptible to experimental pulmonary, but not systemic, Cryptococcus infection. | [82] |

| No significant difference in mortality observed between WT and TLR2 KO mice infected via i.p. inoculation. However, TLR2 KO mice experienced significant increases in fungal burden and decreases in pro-inflammatory cytokine responses. | [83] | |||

| Limited role for TLR2 in host response to C. neoformans. | [84] | |||

| TLR2 is not required for clearance of GXM found in serum. | [85] | |||

| TLR2/TLR1 and TLR2/TLR6 | GXM | HEK293 | GXM from various Cryptococcus serotypes were differentially recognized by TLR2/TLR1 and TLR2/TLR6 heterodimers expressed on TLR-transfected HEK293 cells. | [86] |

| TLR2/CD14 | GXM | CHO cells | CHO cells transfected with both CD14 and TLR2 were not activated in response to Cryptococcus GXM. | [87] |

| TLR4/CD14 | GXM | CHO cells | CHO cells transfected with both CD14 and TLR4 were activated in response to Cryptococcus GXM. | [87] |

| TLR4 | GXM | C3H/HeJ | No significant difference in mortality observed in C3H/HeN mice compared to C3H/HeJ mice with loss of functional TLR4 receptor. | [83] |

| TLR4 KO (C57B1/6) | No significant difference in pulmonary pro-inflammatory cytokine production in infected TLR4 KO mice compared to WT mice. | [84] | ||

| TLR4 is not required for clearance of GXM found in serum. | [85] | |||

| TLR9 | Cryptococcosis DNA | TLR9 KO (C57B1/6) | TLR9 KO mice were more susceptible to experimental pulmonary cryptococcosis. | [88] |

| TLR9 KO mice showed increased fungal burden and decreased Rh1-type cytokine responses. | [89] | |||

| Dectin-1 (CLEC7A, CLECSF12, CD369) | β-glucans | Dectin-1 KO (C57B1/6) | Dectin-1 receptor is dispensable for recognition of cryptococcal yeast and spores. | [90,91] |

| Dectin-2 (CLEC6A, CLEC4N) | α-mannans | Dectin-2 KO (C57B1/6) | Dectin-2 KO mice lacked effective protective Th1 or Th17 responses and, interested, demonstrated elevated Th2-type cytokine responses. | [92] |

| NFAT-GFP reporter cells | Dectin-2 NFAT-GFP reporter system did not recognize Cryptococcus. | [93] | ||

| Dectin-3 (MCL, CLEC4D, CLECSF8) | α-mannans? | Dectin-3 KO (C57B1/6) | Dectin-3 facilitates recruitment of pDCs to the lungs. However, Dectin-3 is dispensable for recognition and phagocytosis of Cryptococcus by pulmonary macrophages and DCs. | [94,95] |

| Mincle (CLEC4E, CLECSF9) | Glycerol-glycolipid | NFAT-GFP reporter cells | Mincle NFAT-GFP reporter system did not recognize Cryptococcus. | [96] |

| Mannose Receptor (CD206) | Mannose and chitin | Mannose Receptor KO (C57B1/6) | Mannose receptor expression on DCs were necessary for phagocytosis of Cryptococcus and stimulation of CD4+ T cells. | [97] |

| DV-SIGN (SIGNR, CD209) | mannoprotein | K562 cell line | Transfected DC-SIGN cells had an increased affinity to cryptococcal mannoproteins. | [98] |

| NLRP3 | Internalized pathogens | NLRP3 KO (C57B1/6) | NLRP3 is activated in the presence of acapsular and capsular Cryptococcus, resulting in internalization and effective cryptococcal killing. | [99,100] |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Campuzano, A.; Wormley, F.L., Jr. Innate Immunity against Cryptococcus, from Recognition to Elimination. J. Fungi 2018, 4, 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof4010033

Campuzano A, Wormley FL Jr. Innate Immunity against Cryptococcus, from Recognition to Elimination. Journal of Fungi. 2018; 4(1):33. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof4010033

Chicago/Turabian StyleCampuzano, Althea, and Floyd L. Wormley, Jr. 2018. "Innate Immunity against Cryptococcus, from Recognition to Elimination" Journal of Fungi 4, no. 1: 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof4010033

APA StyleCampuzano, A., & Wormley, F. L., Jr. (2018). Innate Immunity against Cryptococcus, from Recognition to Elimination. Journal of Fungi, 4(1), 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof4010033