Characterization of Members of the Fusarium incarnatum–equiseti Species Complex from Natural and Cultivated Grasses Intended for Grazing Cattle in Argentina

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Origin of Isolates Examined

2.2. DNA Extraction, Amplification and Sequencing

2.3. Sequence Analysis and Phylogenetic Analysis

2.4. Zearalenone Production

2.5. Zearalenone Analysis

3. Results

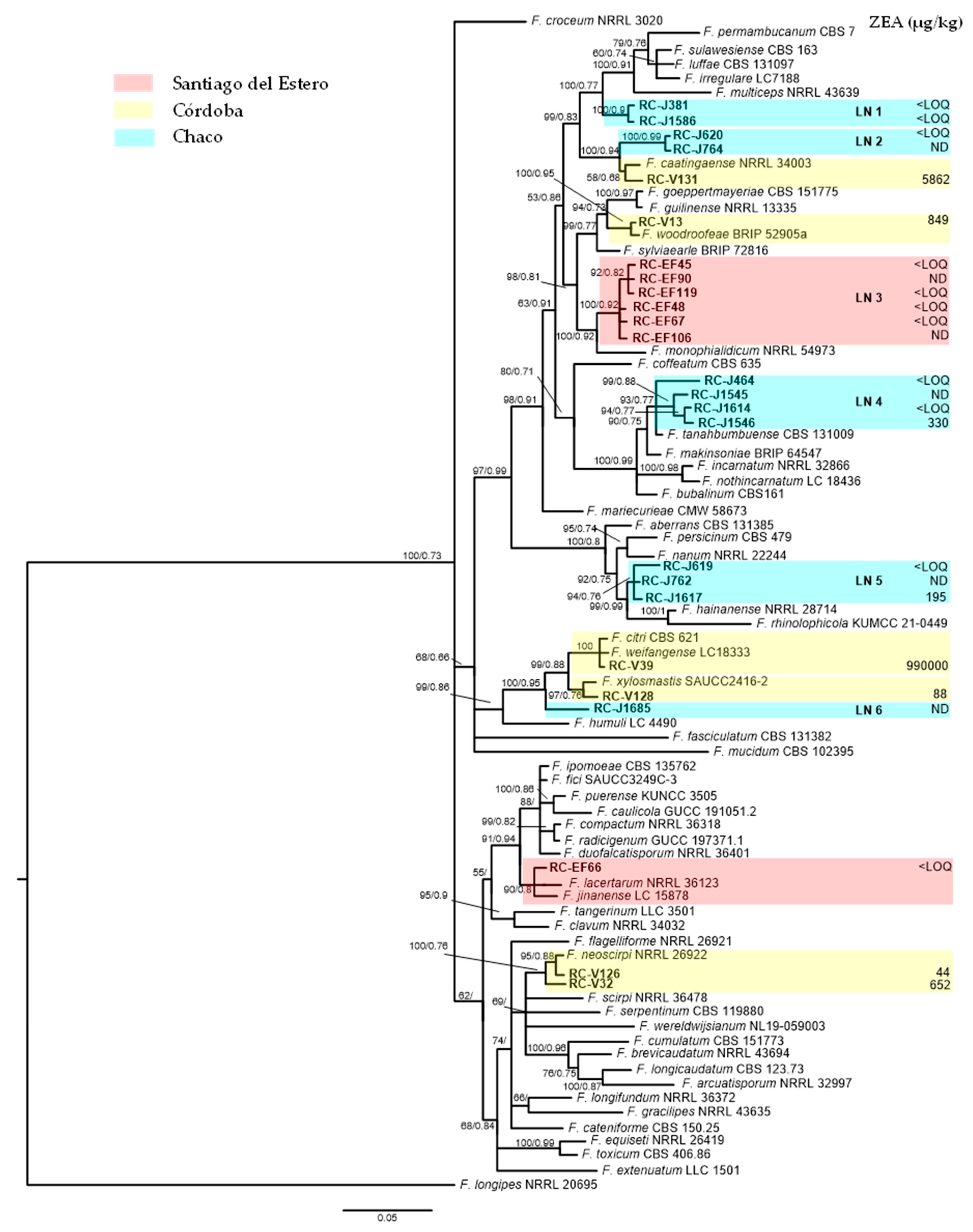

3.1. Phylogenetic Analyses

3.2. ZEA Production

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arelovich, H.M.; Bravo, R.D.; Martinez, M.F. Development, characteristic, and trends for beef cattle production in Argentina. Anim. Front. 2011, 1, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourke, C.A. A review of kikuyu grass (Pennisetum clandestinum) poisoning in cattle. Aust. Vet. J. 2007, 85, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryley, M.; Bourke, C.; Liew, E.C.Y.; Summerell, B. Is Fusarium torulosum the causal agent of kikuyu poisoning in Australia? Australas. Plant Dis. Notes 2007, 2, 133–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botha, C.J.; Truter, M.; Jacobs, A. Fusarium species isolated from Pennisetum clandestinum collected during outbreaks of kikuyu poisoning in cattle in South Africa. Onderstepoort J. Vet. Res. 2014, 81, e1–e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golinski, P.; Kostechi, M.; Golinska, B.T.; Golinsky, P.K. Accumulation of mycotoxins in forage for winter pasture during prolonged utilisation of sward. Pol. J. Vet. Sci. 2003, 6, 81–88. [Google Scholar]

- Driehuis, F.; Spanjer, M.C.; Scholten, J.M.; Te Giffel, M.C. Occurrence of mycotoxins in maize, grass and wheat silage for dairy cattle in the Netherlands. Food Addit. Contam. Part B Surveill. 2008, 1, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skládanka, J.; Nedělník, J.; Adam, V.; Doležal, P.; Moravcová, H.; Dohnal, V. Forage as a primary source of mycotoxins in animal diets. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2011, 8, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erasmuson, A.F.; Scahill, B.G.; West, D.M. Natural zeranol (α-zearalanol) in the urine of pasture-fed animals. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1984, 42, 2721–2725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, C.O.; Erasmuson, A.F.; Wilkins, A.L.; Towers, N.R.; Smith, B.L.; Garthwaite, I.; Scahill, B.G.; Hansen, R.P. Ovine metabolism of zearalenone to α-zearalanol (zeranol). J. Agric. Food Chem. 1996, 44, 3244–3250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Launay, F.M.; Ribeiro, L.; Alves, P.; Vozikis, V.; Tsitsamis, S.; Alfredsson, G.; Sterk, S.S.; Blokland, M.; Litia, A.; Lövgren, T.; et al. Prevalence of zeranol, taleranol and Fusarium spp. toxins in urine: Implications for the control of zeranol abuse in the European Union. Food Addit. Contam. 2004, 21, 833–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, K.F.M.; Moore, D.D. A preliminary survey of zearalenone and other mycotoxins in Australian silage and pasture. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2009, 49, 696–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichea, M.J.; Palacios, S.A.; Chiacchiera, S.M.; Sulyok, M.; Krska, R.; Chulze, S.N.; Torres, A.M.; Ramirez, M.L. Presence of multiple mycotoxins and other fungal metabolites in native grasses from a wetland ecosystem in Argentina intended for grazing cattle. Toxins 2015, 7, 3309–3329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, D.G.; Hewitt, S.A.; McEvoy, J.D.; Currie, J.W.; Cannavan, A.; Blanchflower, W.J.; Elliot, C.T. Zeranol is formed from Fusarium sp. toxins in cattle in vivo. Food Adit. Contam. 1998, 15, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.F.; Morris, C.A. Review of zearalenone studies with sheep in New Zealand. Proc. N. Z. Soc. Anim. Prod. 2006, 66, 306–310. [Google Scholar]

- Nichea, M.J.; Proctor, R.H.; Probyn, C.E.; Palacios, S.A.; Cendoya, E.; Sulyok, M.; Chulze, S.N.; Torres, A.M.; Ramirez, M.L. Fusarium chaquense, sp. nov, a novel type A trichothecene–producing species from native grasses in a wetland ecosystem in Argentina. Mycologia 2022, 114, 46–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aranega, J.P.; Oliveira, C.A. Occurrence of mycotoxins in pastures: A systematic review. QASCF 2022, 14, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, V.C.; Karapanos, I. Decoding potential co-relation between endosphere microbiomecommunity composition and mycotoxin production in forage grasses. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zachetti, V.G.L.; Nichea, M.J.; Sulyok, M.; Torres, A.M.; Chulze, S.N.; Ramirez, M.L. Mycotoxin contamination in natural grasses (Poaceae) intended for grazing cattle in Argentina. Toxins 2017, 9, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Qiu, J.; Wang, S.; Xu, J.; Ma, G.; Shi, J.; Bao, Z. Species diversity and toxigenic potential of Fusarium incarnatum-equiseti species complex isolates from rice and soybean in China. Plant Dis. 2021, 5, 2628–2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, C.; Liu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Li, D.; Geng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Xia, J. Morphological and phylogenetic analyses reveal new species and records of Fusarium (Nectriaceae, Hypocreales) from China. MycoKeys 2025, 116, 53–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munkvold, G.P.; Proctor, R.H.; Moretti, A. Mycotoxin production in Fusarium according to contemporary species concepts. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2021, 59, 373–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, J.F.; Summerell, B.A. The Fusarium Laboratory Manual; Blackwell Professional Publishing: Ames, IA, USA; Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell, K.; Cigelnik, E.; Nirenberg, H.I. Molecular systematics and phylogeography of the Gibberella fujikuroi species complex. Mycologia 1998, 90, 465–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, T.A. BioEdit: A user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 1999, 41, 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Katoh, K.; Rozewicki, J.; Yamada, K. MAFFT online service: Multiple sequence alignment, interactive sequence choice and visualization. Brief. Bioinform. 2017, 20, 1160–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guindon, S.; Dufayard, J.-F.; Lefort, V.; Anisimova, M.; Hordijk, W.; Gascuel, O. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: Assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst. Biol. 2010, 59, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronquist, F.; Teslenko, M.; Van Der Mark, P.; Ayres, D.L.; Darling, A.; Höhna, S.; Larget, B.; Liu, L.; Suchard, M.A.; Huelsenbeck, J.P. MrBayes 3.2: Efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 2012, 61, 539–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darriba, D.; Taboada, G.L.; Doallo, R.; Posada, D. jModelTest 2: More models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacina, O.; Zachariasova, M.; Urbanova, J.; Vaclavikova, M.; Cajka, T.; Hajslova, J. Critical assessment of extraction methods for the simultaneous determination of pesticide residues and mycotoxins in fruits, cereals, spices and oil seeds employing ultra-high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2012, 2, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzuman, Z.; Zachariasova, M.; Veprikova, Z.; Godula, M.; Hajslova, J. Multi-analyte high performance liquid chromatography coupled to high resolution tandem mass spectrometry method for control of pesticide residues, mycotoxins, and pyrrolizidine alkaloids. Anal. Chim. Acta 2015, 10, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, A.R.; Petrovic, T.; Griffiths, S.P.; Burgess, L.W.; Summerell, B.A. Crop pathogens and other Fusarium species associated with Austrostipa aristiglumis. Australas. Plant Pathol. 2007, 36, 434–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nor Azliza, I.N.; Hafizi, R.; Nurhazrati, M.; Salleh, B. Production of major mycotoxins by Fusarium species isolated from wild grasses in peninsular Malaysia. Sains Malays. 2014, 43, 89–94. [Google Scholar]

- Elmer, W.H.; Robert, E.; Marra, R.E.; Li, H.; Li, B. Incidence of Fusarium spp. on the invasive Spartina alterniflora on Chongming Island, Shanghai, China. Biol. Invasions 2016, 18, 2221–2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.M.; Melo, M.P.; Carmo, F.S.; Moreira, G.M.; Guimarães, E.A.; Rocha, F.S.; Costa, S.S.; Abreu, L.M.; Pfenning, L.H. Fusarium species from tropical grasses in Brazil and description of two new taxa. Mycol. Prog. 2021, 20, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Ji, M.; Ze, S.; Wang, H.; Yang, B.; Hu, L.; Zhao, N. Identification and pathogenicity of Fusarium Species from herbaceous plants on grassland in Qiaojia County, China. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tralamazza, S.M.; Piacentini, K.C.; Savi, G.D.; Carnielli-Queiroz, L.; de Carvalho Fontes, L.; Martins, C.S.; Corrêa, B.; Rocha, L.O. Wild rice (O. latifolia) from natural ecosystems in the Pantanal region of Brazil: Host to Fusarium incarnatum-equiseti species complex and highly contaminated by zearalenone. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2021, 345, 109127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewing, C.; Visagie, C.M.; Steenkamp, E.T.; Wingfield, B.D.; Yilmaz, N. Three new species of Fusarium (Nectriaceae, Hypocreales) isolated from Eastern Cape dairy pastures in South Africa. MycoKeys 2025, 115, 241–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villani, A.; Moretti, A.; Saeger, S.D.; Han, Z.; Mavungu, J.D.D.; Soares, C.M.G.; Proctor, R.H.; Venâncio, A.; Lima, N.; Stea, G.; et al. A polyphasic approach for characterization of a collection of cereal isolates of the Fusarium incarnatum-equiseti species complex. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2016, 234, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila, C.F.; Moreira, G.M.; Nicolli, C.P.; Gomes, L.B.; Abreu, L.M.; Pfenning, L.H.; Haidukowski, M.; Moretti, A.; Logrieco, A.; Del Ponte, E.M. Fusarium incarnatum-equiseti species complex associated with Brazilian rice: Phylogeny, morphology and toxigenic potential. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2019, 306, 108267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, G.M.; Nicolli, C.P.; Gomes, L.B.; Ogoshi, C.; Scheuermann, K.K.; Silva-Lobo, V.L.; Schurt, D.A.; Ritieni, A.; Moretti, A.; Pfenning, L.H.; et al. Nationwide survey reveals high diversity of Fusarium species and related mycotoxins in Brazilian rice: 2014 and 2015 harvests. Food Control 2020, 113, 107171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jedidi, I.; Jurado, M.; Cruz, A.; Trabelsi, M.M.; Said, S.; González-Jaén, M.T. Phylogenetic analysis and growth profiles of Fusarium incarnatum-equiseti species complex strains isolated from Tunisian cereals. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2021, 353, 109297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.L.; Wang, M.M.; Ma, Z.Y.; Raza, M.; Zhao, P.; Liang, J.M.; Gao, M.; Li, Y.J.; Wang, J.W.; Hu, D.M.; et al. Fusarium diversity associated with diseased cereals in China, with an updated phylogenomic assessment of the genus. Stud. Mycol. 2023, 104, 87–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, K.; McCormick, S.P.; Busman, M.; Proctor, R.H.; Ward, T.J.; Doehring, G.; Geiser, D.M.; Alberts, J.F.; Rheeder, J.P. Marasas et al. 1984 “Toxigenic Fusarium species: Identity and mycotoxicology” revisited. Mycologia 2018, 110, 1058–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.P.; Bishop-Hurley, S.L.; Marney, T.S.; Marney, R.G. Nomenclatural novelties. Index Aust. Fungi 2025, 54, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Nuangmek, W.; Suwannarach, N.; Sukyai, S.; Khitka, B.; Kumla, J. Fungal pathogens causing postharvest anthracnose and fruit rot in Indian jujube (Ziziphus mauritiana) from northern Thailand and their fungicide response profiles. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1634557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beacorn, J.A.; Thiessen, L.D. First Report of Fusarium lacertarum causing Fusarium head blight on sorghum in North Carolina. Plant Dis. 2021, 105, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do Amaral, A.C.T.; Koroiva, R.; da Costa, A.F.; Lima, C.S.; de Oliveira, N.T. First report of Fusarium lacertarum as the causal agent of wilt in Vigna unguiculata. J. Plant Pathol. 2022, 104, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago, M.F.; Santos, A.M.G.; Inácio, C.P.; Neto, A.C.L.; Assis, T.C.; Neves, R.P.; Doyle, V.P.; Veloso, J.S.; Vieira, W.A.S.; Câmara, M.P.S.; et al. First report of Fusarium lacertarum causing cladode rot in Nopalea cochenellifera in Brazil. J. Plant Pathol. 2018, 100, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.C.D.S.; Trindade, J.V.C.; Lima, C.S.; Barbosa, R.D.N.; da Costa, A.F.; Tiago, P.V.; de Oliveira, N.T. Morphology, phylogeny, and sexual stage of Fusarium caatingaense and Fusarium pernambucanum, new species of the Fusarium incarnatum-equiseti species complex associated with insects in Brazil. Mycologia 2019, 111, 244–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maciel, M.; do Amaral, A.C.T.; da Silva, T.D.; Bezerra, J.D.P.; de Souza-Motta, C.M.; da Costa, A.F.; Tiago, P.V.; de Oliveira, N.T. Evaluation of mycotoxin production and phytopathogenicity of the entomopathogenic fungi Fusarium caatingaense and F. pernambucanum from Brazil. Curr. Microbiol. 2021, 78, 1218–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, J.W.; Sandoval-Denis, M.; Crous, P.W.; Zhang, X.G.; Lombard, L. Numbers to names—Restyling the Fusarium incarnatum-equiseti species complex. Persoonia 2019, 43, 186–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Strain Code | Year | Host | Geographic Origin | GPS Coordinates | GenBank Accession Number TEF1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RC-J381 | 2011 | Poaceae | Chaco | 27°31′36.8″ S, 59°05′03.8″ W | PX363448 |

| RC-J464 | 2011 | Poaceae | Chaco | 27°31′25.6″ S, 59°05′00.5″ W | PX363449 |

| RC-J762 | 2011 | Poaceae | Chaco | 27°33′54.4″ S, 60°24′44.6″ W | PX363452 |

| RC-J619 | 2011 | Poaceae | Chaco | 27°33′28.2″ S, 60°25′05.3″ W | PX363450 |

| RC-J620 | 2011 | Poaceae | Chaco | 27°33′28.2″ S, 60°25′05.3″ W | PX363451 |

| RC-J764 | 2011 | Poaceae | Chaco | 27°33′54.4″ S, 60°24′44.6″ W | PX363453 |

| RC-J1586 | 2014 | Spartina sp. | Chaco | 27°30′49.5″ S, 59°05′06.1″ W | PX363454 |

| RC-J1545 | 2014 | Chloris sp. | Chaco | 27°30′49.5″ S, 59°05′06.1″ W | PX363458 |

| RC-J1546 | 2014 | Chloris sp. | Chaco | 27°30′49.5″ S, 59°05′06.1″ W | PX363459 |

| RC-J1685 | 2014 | Eragrostis sp. | Chaco | 27°31′07.0″ S, 59°05′00.9″ W | PX363457 |

| RC-J1614 | 2014 | Panicum sp. | Chaco | 27°30′49.5″ S, 59°05′06.1″ W | PX363455 |

| RC-J1617 | 2014 | Panicum sp. | Chaco | 27°30′49.5″ S, 59°05′06.1″ W | PX363456 |

| RC-EF45 | 2022 | Megathyrsus maximus | Santiago del Estero | 27°08′02.07″ S, 61°51′34.94″ W | PX363441 |

| RC-EF90 | 2022 | Megathyrsus maximus | Santiago del Estero | 27°08′02.07″ S, 61°51′34.94″ W | PX363445 |

| RC-EF119 | 2022 | Megathyrsus maximus | Santiago del Estero | 27°08′02.07″ S 61°51′34.94″ W | PX363447 |

| RC-EF48 | 2022 | Megathyrsus maximus | Santiago del Estero | 27°08′02.07″ S, 61°51′34.94″ W | PX363442 |

| RC-EF67 | 2022 | Megathyrsus maximus | Santiago del Estero | 27°08′02.07″ S, 61°51′34.94″ W | PX363444 |

| RC-EF106 | 2022 | Megathyrsus maximus | Santiago del Estero | 27°08′02.07″ S, 61°51′34.94″ W | PX363446 |

| RC-EF66 | 2022 | Megathyrsus maximus | Santiago del Estero | 27°08′02.07″ S, 61°51′34.94″ W | PX363443 |

| RC-V13 | 2016 | Aristida laevis | Córdoba | 32°44.661′ S, 64°47.251′ W | PX363463 |

| RC-V32 | 2016 | Paspalum quadrifarium | Córdoba | 32°44.805′ S, 64°46.440′ W | PX363464 |

| RC-V39 | 2016 | Paspalum notatum | Córdoba | 32°44.803′ S, 64°46.440′ W | PX363462 |

| RC-V126 | 2016 | Melinis repens | Córdoba | 32°44.806′ S, 64°46.697′ W | PX363460 |

| RC-V128 | 2016 | Panicum sp. | Córdoba | 32°44.727′ S, 64°46.706′ W | PX363465 |

| RC-V131 | 2016 | Aristida laevis | Córdoba | 32°44.661′ S, 64°47.251′ W | PX363461 |

| Fusarium Species | Strain Number | GenBank Accession Number TEF1 |

|---|---|---|

| F. aberrans | CBS 131385 | MN170445.1 |

| F. arcuatisporum | NRRL 32997 | GQ505624 |

| F. brevicaudatum | NRRL 43694 | GQ505665 |

| F. bubalinum | CBS 161.25 | MN170448 |

| F. caatingaense | NRRL 34003 | MN170449.1 |

| F. cateniforme | CBS 150.25 | MN170451 |

| F. caulicola | GUCC 191051.2 | OR043884.1 |

| F. citri | CBS 621.87 | MN170452.1 |

| F. clavum | NRRL 34032 | GQ505635 |

| F. coffeatum | CBS 635.76 | MN120755.1 |

| F. compactum | NRRL 36318 | GQ505646 |

| F. concolor | NRRL 13459 | GQ505674.1 |

| F. croceum | NRRL 3020 | GQ505586 |

| F. cumulatum | CBS 151773 | OR671087.1 |

| F. duofalcatisporum | NRRL 36401 | GQ505651 |

| F. equiseti | NRRL 26419 | GQ505599.1 |

| F. extenuatum | LLC1501 | OP487158.1 |

| F. fasciculatum | CBS 131382 | MN170473.1 |

| F. fici | SAUCC3249C-3 | PQ309133.1 |

| F. flagelliforme | NRRL 26921 | GQ505600 |

| F. goeppertmayeriae | CBS 151775 | OR670981.1 |

| F. gracilipes | NRRL 43635 | GQ505662.1 |

| F. guilinense | NRRL 13335 | GQ505590 |

| F. hainanense | NRRL 28714 | MN170510.1 |

| F. humuli | LC4490 | MK289614.1 |

| F. incarnatum | NRRL 32866 | GQ505615 |

| F. ipomoeae | CBS 135762 | MN170478.1 |

| F. irregulare | LC7188 | MK289629.1 |

| F. jinanense | LC15878 | OQ125131.1 |

| F. lacertarum | NRRL 36123 | GQ505643 |

| F. longicaudatum | CBS 123.73 | MN170481 |

| F. longifundum | NRRL 36372 | GQ505649 |

| F. longipes | NRRL 20695 | GQ915509 |

| F. luffae | CBS 131097 | MN170482.1 |

| F. makinsoniae | BRIP 64547 | OQ626867 |

| F. mariecurieae | CMW 58673 | OR671063.1 |

| F. monophialidicum | NRRL 54973 | MN170483 |

| F. mucidum | CBS 102395 | MN170485.1 |

| F. multiceps | NRRL 43639 | GQ505666.1 |

| F. nanum | NRRL 22244 | MN170486.1 |

| F. neoscirpi | NRRL 26922 | GQ505601 |

| F. nothincarnatum | LC18436 | OQ125147 |

| F. pernambucanum | CBS 791.70 | MN170491.1 |

| F. persicinum | CBS 479.83 | MN170495.1 |

| F. puerense | KUNCC 3505 | PV464279.1 |

| F. radicigenum | GUCC 197371.1 | OR043907.1 |

| F. rhinolophicola | KUMCC 21-0449 | OR026001.1 |

| F. scirpi | NRRL 36478 | GQ505654 |

| F. serpentinum | CBS 119880 | MN170499 |

| F. sulawesiense | CBS 163.57 | MN170501.1 |

| F. sylviaearle | BRIP 72816 | OR269444 |

| F. tanahbumbuense | CBS 131009 | MN170506.1 |

| F. tangerinum | LLC3501 | OP487189.1 |

| F. toxicum | CBS 406.86 | MN170508 |

| F. weifangense | LC18333 | OQ125107.1 |

| F. wereldwijsianum | NL19-059003 | MZ921852.1 |

| F. xylosmatis | SAUCC2416-2 | PQ309132.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Nichea, M.J.; Cendoya, E.; Zachetti, V.G.; Demonte, L.D.; Repetti, M.R.; Palacios, S.A.; Ramirez, M.L. Characterization of Members of the Fusarium incarnatum–equiseti Species Complex from Natural and Cultivated Grasses Intended for Grazing Cattle in Argentina. J. Fungi 2026, 12, 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof12010026

Nichea MJ, Cendoya E, Zachetti VG, Demonte LD, Repetti MR, Palacios SA, Ramirez ML. Characterization of Members of the Fusarium incarnatum–equiseti Species Complex from Natural and Cultivated Grasses Intended for Grazing Cattle in Argentina. Journal of Fungi. 2026; 12(1):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof12010026

Chicago/Turabian StyleNichea, María Julia, Eugenia Cendoya, Vanessa Gimena Zachetti, Luisina Delma Demonte, María Rosa Repetti, Sofia Alejandra Palacios, and María Laura Ramirez. 2026. "Characterization of Members of the Fusarium incarnatum–equiseti Species Complex from Natural and Cultivated Grasses Intended for Grazing Cattle in Argentina" Journal of Fungi 12, no. 1: 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof12010026

APA StyleNichea, M. J., Cendoya, E., Zachetti, V. G., Demonte, L. D., Repetti, M. R., Palacios, S. A., & Ramirez, M. L. (2026). Characterization of Members of the Fusarium incarnatum–equiseti Species Complex from Natural and Cultivated Grasses Intended for Grazing Cattle in Argentina. Journal of Fungi, 12(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof12010026