The Conservation Crisis of Ophiocordyceps sinensis: Strategies, Challenges, and Sustainable Future of Artificial Cultivation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Depletion of Wild O. sinensis Resources and Soaring Market Demand

2.1. Distribution of Wild O. sinensis and Multiple Drivers of Its Decline

2.2. Market Value and Demand

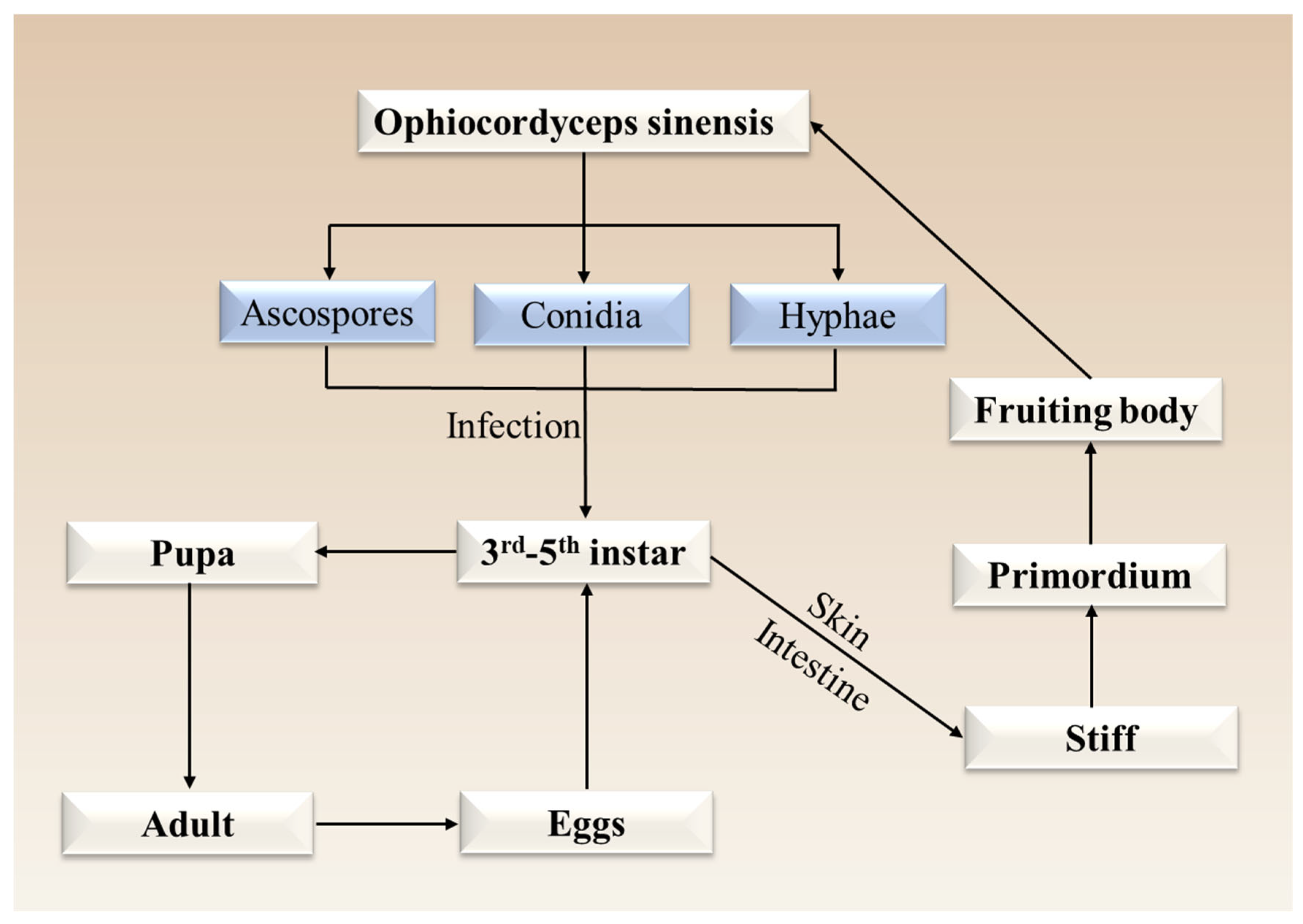

3. Two Approaches to the Artificial Cultivation of O. sinensis

3.1. Mycelial Fermentation

3.1.1. Fungal Species

3.1.2. Industrial Fermentation Production

| Species | Wild Distribution | Chemical Constituents | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ophiocordyceps sinensis | Tibet, Qinghai, Sichuan, Yunnan, and Gansu provinces | Adenosine, cordycepin, mannitol, polysaccharides, ergosterol, glutamic acid, arginine, tryptophan, tyrosine, trace elements, vitamins | [8,9] |

| Cordyceps militaris | Yunnan, Guizhou, Sichuan, Chongqing | Adenosine, cordycepin, N6-(2-hydroxyethyl)-adenosine, pentostatin, adenine, 2′-deoxyuridine, mannitol, polysaccharides, albumin, glutelin, globulin, γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), ergothioneine, lovastatin, sterols, cerebroside B | [4,93,94,95,96,97,98] |

| Cordyceps chanhua | Zhejiang, Jiangsu, Anhui, Hubei, Hunan, Guangdong, Sichuan, Yunnan, Fujian, and Taiwan | Polysaccharides, nucleosides, mannitol, ergosterol, myriocin, amino acids | [99] |

| Tolypocladium guangdongense | Guangdong | Adenosine, cordycepin, mannitol, glutamic acid, arginine | [100,101] |

3.2. Bio-Cultivation of O. sinensis

3.2.1. Host Insect Species of O. sinensis

3.2.2. Rearing of Host Insects

| Inoculation Method | Procedure | References |

|---|---|---|

| Cuticular Infection | Topical application of suspensions containing ascospores, conidia, or mycelia. | [125,126] |

| Infection of larvae with fungal mycelial mats. | [46] | |

| Laser-induced micro-abrasions followed by spore application. | [47] | |

| Oral Infection | Feeding larvae with symbiotic complexes of H. sinensis (the anamorph of O. sinensis) and plant tissues. | [127] |

| Internal Injection | Direct micro-injection of mycelial and conidial suspensions using a needle | [128] |

| Injection of blastospore mixtures. | [129] |

4. Conclusions and Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Qian, G.M.; Pan, G.F.; Guo, J.Y. Anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive effects of cordymin, a peptide purified from the medicinal mushroom Cordyceps sinensis. Nat. Prod. Res. 2012, 26, 2358–2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Xu, B.J.; Zhao, L.B.; Li, L.; Xu, K.Y.; Tang, A.Q.; Zhou, S.S.; Song, L.; Zhang, X.; et al. Based on network pharmacology tools to investigate the molecular mechanism of Cordyceps sinensis on the treatment of diabetic nephropathy. J. Diabetes Res. 2021, 2021, 8891093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, W.M.; Mao, X.B.; Li, C.F.; Zhu, L.C.; He, Z.Y.; Wang, B.C. Mannitol mediates the mummification behavior of Thitarodes xiaojinensis larvae infected with Ophiocordyceps sinensis. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1411645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.T.; Sun, S.J.; Fang, J.W. Brief of similarities and differences between Cordyceps militaris and Cordyceps sinensis. J. Liaoning Univ. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2014, 16, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, R.C.; Wu, H.; Tao, H.P.; Qiu, X.H.; Liu, G.Q.; Rao, Z.C.; Cao, L. Research on Chinese Cordyceps during the past 70 years in China. Chin. J. Appl. Entomol 2019, 56, 849–883. [Google Scholar]

- Ong, B.Y.; Aziz, Z. Efficacy of Cordyceps sinensis as an adjunctive treatment in kidney transplant patients: A systematic-review and meta-analysis. Complement. Ther. Med. 2017, 30, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, S.A.; Elkhalifa, A.E.O.; Siddiqui, A.J.; Patel, M.; Awadelkareem, A.M.; Snoussi, M.; Ashraf, M.S.; Adnan, M.; Hadi, S. Cordycepin for Health and Wellbeing: A potent bioactive metabolite of an entomopathogenic medicinal fungus Cordyceps with its nutraceutical and therapeutic potential. Molecules 2020, 25, 2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olatunji, O.J.; Tang, J.; Tola, A.; Auberon, F.; Oluwaniyi, O.; Ouyang, Z. The genus Cordyceps: An extensive review of its traditional uses, phytochemistry and pharmacology. Fitoterapia 2018, 129, 293–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Llerena, J.L.; Treviño-Almaguer, D.; Leal-Mendez, J.A.; Garcia-Valdez, G.; Balderas-Moreno, A.G.; Heya, M.S.; Balderas-Renteria, I.; Camacho-Corona, M.d.R.; Espinosa-Rodriguez, B.A. The Cordyceps genus as a potential source of bioactive compounds for adjuvant cancer therapy: A network pharmacology approach. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Liu, L.; Rao, B.F.; Gao, X.Y. Research status of immunosuppressive effects of Ophiocordyceps sinensis. J. North. Sichuan Med. Coll. 2001, 2, 108–110. [Google Scholar]

- Jędrejko, K.J.; Lazur, J.; Muszyńska, B. Cordyceps militaris: An overview of its chemical constituents in relation to biological activity. Foods 2021, 10, 2634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.X.; Yang, E.C.; Li, Y.L.; Liu, X.Z. Clarifying terms on Chinese Cordyceps from different scientific subjects, industry and public. J. Fungal Res. 2020, 18, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.H.; Li, W.J.; Li, Z.Z.; Yan, W.J.; Li, T.H.; Liu, X.Z.; Cai, L.; Zeng, W.B.; Chai, M.Q.; Chen, S.J.; et al. Cordyceps industry in China: Current status, challenges and perspectives—Jinhu declaration for Cordyceps industry development. Mycosystema 2016, 35, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yan, Y.J.; Tang, Z.Y.; Wang, K.; He, S.J.; Yao, Y.J. Conserving the Chinese caterpillar fungus under climate change. Biodivers. Conserv. 2021, 30, 547–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martel, J.; Ko, Y.F.; Liau, J.C.; Lee, C.S.; Ojcius, D.M.; Lai, H.C.; Young, J.D. Myths and realities surrounding the mysterious caterpillar fungus. Trends Biotechnol. 2017, 35, 1017–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, W.; Zhang, G.R.; Peng, Q.Y.; Liu, X. Development of Ophiocordyceps sinensis through plant-mediated interkingdom host colonization. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 17482–17493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrestha, U.B. Asian medicine: A fungus in decline. Nature 2012, 482, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennike, R.B.; Nielsen, M.R.; Smith-Hall, C. Do high-value environmental products provide a pathway out of poverty? The case of the world’s most valuable fungus (Ophiocordyceps sinensis). Environ. Dev. 2025, 56, 101281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, R. Mycology. Last stand for the body snatcher of the Himalayas? Science 2008, 322, 1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, K.V.; Balasubramanian, B.; Park, S.; Bhattacharya, S.; Sebastian, J.K.; Liu, W.C.; Pappuswamy, M.; Meyyazhagan, A.; Kamyab, H.; Chelliapan, S.; et al. Conservation of endangered Cordyceps sinensis through artificial cultivation strategies of C. militaris, an alternate. Mol. Biotechnol. 2025, 67, 1382–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, U.B.; Bawa, K.S. Impact of climate change on potential distribution of Chinese caterpillar fungus (Ophiocordyceps sinensis) in Nepal Himalaya. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e106405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopping, K.A.; Chignell, S.M.; Lambin, E.F. The demise of caterpillar fungus in the Himalayan region due to climate change and overharvesting. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 11489–11494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, G.L.; Wang, F.; Dong, C.H. Chinese Cordyceps products, geographic traceability and authenticity assessment: Current status, challenges, and future directions. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2025, 45, 1435–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Liu, Q.; Li, W.J.; Li, Q.P.; Qian, Z.M.; Liu, X.Z.; Dong, C.H. A breakthrough in the artificial cultivation of Chinese Cordyceps on a large-scale and its impact on science, the economy, and industry. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2019, 39, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, C.H.; Guo, S.P.; Wang, W.F.; Liu, X.Z. Cordyceps industry in China. Mycology 2015, 6, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Z.; Cao, L.; Zhang, Y.; Ye, Y.S.; Han, R.C. Laboratory rearing of Thitarodes armoricanus and Thitarodes jianchuanensis (Lepidoptera: Hepialidae), hosts of the Chinese medicinal fungus Ophiocordyceps sinensis (Hypocreales: Ophiocordycipitaceae). J. Econ. Entomol 2016, 109, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.R.; Tian, Z.Y.; Fan, Q.; Li, D.D.; Wang, Y.B.; Huang, L.D. Research status and sustainable utilization of Ophiocordyceps sinensis. Edible Fungi China 2021, 40, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.H.; Yang, S.S.; Deng, W.Q.; Lin, Q.Y. Cordyceps sensu lato and their domestication and cultivation in China. Acta Edulis Fungi 2023, 30, 113–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, K.V.; Ulhas, R.S.; Malaviya, A. Bioactive compounds from Cordyceps and their therapeutic potential. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2024, 44, 753–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, C.Y.; Zhao, Y.Q.; Zhang, L.; Li, X.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, D.M.; Xu, C.S.; Qi, M.Y.; Wang, J.H.; Guo, X.R.; et al. Myxobacteria restrain phytophthora invasion by scavenging thiamine in soybean rhizosphere via outer membrane vesicle-secreted thiaminase I. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.H.; Cao, L.; Han, R.C. The progress, issues and perspectives in the research of Ophiocordyceps sinensis. J. Environ. Entomol 2016, 38, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.C.; Qiu, J.J.; Qiu, F. Research on sustainable utilization of Cordyceps sinensis resources in Naqu region of Xizang Zizhiqu. Ecol. Econ. 2011, 6, 112–114+126. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, D.C.; Hajjar, R. Forests as pathways to prosperity: Empirical insights and conceptual advances. World Dev. 2020, 125, 104647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.L.; Teng, H.F.; Chen, S.C.; Zhou, Y.; Wan, D.; Shi, Z. Future habitat shifts and economic implications for Ophiocordyceps sinensis under climate change. Ecol. Evol. 2025, 15, e71327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith-Hall, C.; Bennike, R.B. Understanding the sustainability of Chinese caterpillar fungus harvesting: The need for better data. Biodivers. Conserv. 2022, 31, 729–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.W.; Li, L.J.; Tian, E.W. Advances in research of the artificial cultivation of Ophiocordyceps sinensis in China. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2014, 34, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, P.F.; Hywel-Jones, N.L.; Maczey, N.; Norbu, L.; Tshitila; Samdup, T.; Lhendup, P. Steps towards sustainable harvest of Ophiocordyceps sinensis in Bhutan. Biodivers. Conserv. 2009, 18, 2263–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negi, C.S.; Joshi, P.; Bohra, S. Rapid vulnerability assessment of Yartsa Gunbu (Ophiocordyceps sinensis [Berk.] G.H. Sung et al.) in pithoragarh district, Uttarakhand state, India. Mt. Res. Dev. 2015, 35, 382–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Fan, J.F.; An, Y.B.; Meng, G.L.; Ji, B.Y.; Li, Y.; Dong, C.H. Tracing the geographical origin of endangered fungus Ophiocordyceps sinensis, especially from Nagqu, using UPLC-Q-TOF-MS. Food Chem. 2024, 440, 138247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.Z.; Bi, Y.F.; Ye, J.X.; Chen, C.Z.; Bi, X.Y. Origin traceability of Cordyceps sinensis based on trace elements and stable isotope fingerprints. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 169591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.F.; Zhou, K.W.; Liu, Y.; Du, H.J.; Wang, D.H.; Liu, S.M.; Liu, S.; Li, J.G.; Zhao, L.M. A simplified hyperspectral identification system based on mathematical transformation: An example of Cordyceps sinensis geographical origins. Microchem. J. 2024, 205, 111191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.J.; Jin, S.M.; Wang, Y. Natural suitability evaluation of human settlements in Qinghai-Tibet Plateau based on GIS. Ecol. Sci. 2020, 39, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.S.; Zhong, Y.C.; Zhao, J.N.; Dai, Y.; Hua, H.; Yang, A.D.; Zhang, Y.G.; Song, X.R. Research and development thinking and path of American dietary supplement based on Sichuan genuine medicinal materials and TCM classical famous prescriptions. World Chin. Med. 2020, 15, 191–199. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, K. Cordyceps sinensis active extract Cordyceps polysaccharide combined with aerobic exercise improvement suggestions. Edible Fungi China 2019, 38, 42–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.F.; Song, Z.W. Effect of Cordyceps sinensis polysaccharide extract on the complement system of female wrestlers. Edible Fungi China 2019, 38, 27–29+45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhang, L.; Li, M. Application of herbal traditional Chinese medicine in the treatment of lupus nephritis. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 981063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.J.; Ye, M.; Zhou, Z.J.; Song, K.; Dai, Y. A preliminary study on the olfactory response to several plantsof Cordyceps Hepialus larvae. Sichuan J. Zool 2013, 32, 228–231. [Google Scholar]

- Gunter, N.V.; Ong, Y.S.; Lai, Z.W.; Morita, H.; Chamyuang, S.; Owatworakit, A.; Mah, S.H. Anti-cancer effects of Cordyceps sinensis, C. militaris and C. cicadae and their mechanisms of action. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2025, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, K.; Shinozuka, K.; Yoshikawa, N. Anticancer and antimetastatic effects of Cordycepin, an active component of Cordyceps sinensis. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2015, 127, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Cai, H.W.; Sun, H.H.; Qu, J.B.; Zhao, B.; Hu, X.F.; Li, W.J.; Qian, Z.M.; Yu, X.; Kang, F.H.; et al. Extracts of Cordyceps sinensis inhibit breast cancer growth through promoting M1 macrophage polarization via NF-κB pathway activation. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 260, 112969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Tang, Q.J.; Tang, C.H.; Liu, Y.F.; Ma, F.Y.; Zhang, X.Y.; Zhang, J.S. Triterpenes and Soluble Polysaccharide Changes in Lingzhi or Reishi Medicinal Mushroom, Ganoderma lucidum (Agaricomycetes), During Fruiting Growth. Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2018, 20, 859–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zan, K.; Huang, L.L.; Guo, L.N.; Liu, J.; Zheng, J.; Ma, S.C.; Qian, Z.M.; Li, W.J. Comparative study on specific chromatograms and main nucleosides of cultivated and wild Cordyceps sinensis. China J. Chin. Mater. Medica 2017, 42, 3957–3962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Xie, F.; Chen, Z.H.; Zhang, R.R. Research progress on Ophiocordyceps Sinensis compounds. Guangzhou Chem. Ind. 2023, 51, 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.Q.; Sun, M.T.; Li, W.J.; Yang, F.Q.; Tian, Y.; Qian, Z.M. Simultaneous Determination of Three Sterols in Cordyceps sinensis by HPLC-ELSD. J. Li-Shizhen Tradit. Chin. Med. 2018, 29, 862–864. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda, H.; Akaki, J.; Nakamura, S.; Okazaki, Y.; Kojima, H.; Tamesada, M.; Yoshikawa, M. Apoptosis-inducing effects of sterols from the dried powder of cultured mycelium of Cordyceps sinensis. Chem. Pharm. Bull (Tokyo) 2009, 57, 411–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, H.C.; Hsieh, C.; Lin, F.Y.; Hsu, T.H. A systematic review of the mysterious caterpillar fungus Ophiocordyceps sinensis in Dong-ChongXiaCao (Dōng Chóng Xià Cǎo) and related bioactive ingredients. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 2013, 3, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Wang, A.Z.; Cheng, D.Z.; Shen, J.W.; Chen, S.L.; Zhou, D.W. Comparison on the Chemical Constituents between Cultural Cordyceps Militaris and Natural Fruiting Body of Cordyceps Sinensis. Guid. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. Pharm. 2019, 25, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.J.; Jang, K.H.; Im, S.Y.; Lee, Y.K.; Farooq, M.; Farhoudi, R.; Lee, D.J. Physico-chemical properties and cytotoxic potential of Cordyceps sinensis metabolites. Nat. Prod. Res. 2015, 29, 455–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, M.; Zhao, Y.C.; Liu, Y.Y.; Wu, S.R.; Zhao, T.R.; Fan, J. Study on polyphenol extraction of Cordyceps sinensis mycelium and their lnhibitory effect on three kinds of cancer cells. Edible Fungi China 2017, 36, 48–52. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, L.X.; Hong, Y.H.; Zhou, Q.Z.; Zhu, Q.; Xu, X.M.; Wang, J.H. Fungus-larva relation in the formation of Cordyceps sinensis as revealed by stable carbon isotope analysis. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 7789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.Q.; Li, W.J.; Dong, C.H.; Zhou, J.Q.; Qian, Z.M. Determination of Cordycepic acid in cultivated and wild Chinese Cordyceps. J. Fungal Res. 2018, 16, 102–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.S.; Zhong, X.; Li, S.S.; Zhang, G.R.; Liu, X. Metabolic characterization of natural and cultured Ophicordyceps sinensis from different origins by 1H NMR spectroscopy. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2015, 115, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.B.; Liu, J.; Lu, J.G.; Yang, M.R.; Zhang, W.; Li, W.J.; Qian, Z.M.; Jiang, Z.H.; Bai, L.P. Quantitative 1H NMR with global spectral deconvolution approach for quality assessment of natural and cultured Cordyceps sinensis. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2023, 235, 115603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.Q.; Kan, L.J.; Nie, S.P.; Chen, H.H.; Cui, S.W.; Phillips, A.O.; Phillips, G.O.; Li, Y.J.; Xie, M.Y. A comparison of chemical composition, bioactive components and antioxidant activity of natural and cultured Cordyceps sinensis. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 63, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.M.; Zhang, X.; Song, Q.; Lu, W.L.; Wu, T.N.; Zhang, Q.L.; Li, C.R. Determination and comparative analysis of 13 nucleosides and nucleobases in natural fruiting body of Ophiocordyceps sinensis and its substitutes. Mycology 2017, 8, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.X.; Zhang, G.W.; Li, Q.Q.; Xu, X.M.; Wang, J.H. Novel arsenic markers for discriminating wild and cultivated Cordyceps. Molecules 2018, 23, 2804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.J.; Wei, R.S.; Xia, J.M.; Lv, Y.H. Ophiocordyceps sinensis in the intestines of Hepialus larvae. Mycosystema 2016, 35, 450–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Rao, Z.C.; Cao, L.; Clercq, P.D.; Han, R.C. Infection of Ophiocordyceps sinensis fungus causes dramatic changes in the microbiota of its thitarodes host. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 577268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buenz, E.J.; Bauer, B.A.; Osmundson, T.W.; Motley, T.J. The traditional Chinese medicine Cordyceps sinensis and its effects on apoptotic homeostasis. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005, 96, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, G.H.; Hywel-Jones, N.L.; Sung, J.M.; Luangsa-ard, J.J.; Shrestha, B.; Spatafora, J.W. Phylogenetic classification of Cordyceps and the clavicipitaceous fungi. Stud. Mycol. 2007, 57, 5–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.P.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Y.J. Evaluation of biological activities and artificial cultivation of fruiting bodies of Cordyceps blackwelliae. Mycosystema 2022, 41, 1807–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.H.; Yao, Y.J. On the reliability of fungal materials used in studies on Ophiocordyceps sinensis. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 38, 1027–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.H.; Liu, C.; Han, Y.F.; Liang, J.D.; Tian, W.Y.; Liang, Z.Q. Two new recorded species in Cordyceps sensu lato. Microbiol. China 2020, 47, 710–717. [Google Scholar]

- Song, B.; Lin, Q.Y.; Li, T.H.; Shen, Y.H.; Li, J.J.; Luo, D.X. Known species of Cordyceps from China and their distribution. J. Fungal Res. 2006, 4, 10–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Yao, Y.J. Names related to Cordyceps sinensis anamorph. Mycotaxon 2002, 84, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.J.; Guo, Y.L.; Yu, Y.X.; Zeng, W. Isolation and identification of the anamorphic state of Cordyceps sinensis (Berk.) Sacc. Mycosystema 1989, 8, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.W. One Fungus = One Name: DNA and fungal nomenclature twenty years after PCR. IMA Fungus 2011, 2, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turgeon, B.G.; Yoder, O.C. Proposed nomenclature for mating type genes of filamentous ascomycetes. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2000, 31, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, Y.J.; Liu, X.Z.; Wen, H.A.; Wang, M.; Liu, D.S. Cloning and analysis of the MAT1-2-1 gene from the traditional Chinese medicinal fungus Ophiocordyceps sinensis. Fungal Biol. 2011, 115, 708–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushley, K.E.; Raja, R.; Jaiswal, P.; Cumbie, J.S.; Nonogaki, M.; Boyd, A.E.; Owensby, C.A.; Knaus, B.J.; Elser, J.; Miller, D.; et al. The genome of Tolypocladium inflatum: Evolution, organization, and expression of the cyclosporin biosynthetic gene cluster. PLoS Genet. 2013, 9, e1003496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, P.; Xia, Y.L.; Xiao, G.H.; Xiong, C.H.; Hu, X.; Zhang, S.W.; Zheng, H.J.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, S.Y.; et al. Genome sequence of the insect pathogenic fungus Cordyceps militaris, a valued traditional Chinese medicine. Genome Biol. 2011, 12, R116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, S.Y.; Yao, Y.J. Evaluation of nutritional and physical stress conditions during vegetative growth on conidial production and germination in Ophiocordyceps sinensis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2013, 346, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.J.; Li, E.W.; Wang, C.S.; Li, Y.L.; Liu, X.Z. Ophiocordyceps sinensis, the flagship fungus of China: Terminology, life strategy and ecology. Mycology 2012, 3, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.Y.; Liang, G.H.; Liang, L.; Lv, Y.H.; Li, W.J.; Xie, J.J. Effects of medium and environmental conditions on the sporulation of Ophiocordyceps sinensis in solid fermentation. Mycosystema 2016, 35, 440–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, F.; Gui, L.; Li, C.R.; Fan, M.Z. Studies on solid-state fermentation condition of Hirsutella sinensis anamorph of Cordyceps sinensis. J. Biol. 2009, 26, 22–25. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.L. Anamorphs of Cordyceps and artificial cultivation of their fruiting bodies. Guizhou Agric. Sci. 1990, 1, 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Z.Q.; Liu, A.Y.; Liu, M.H.; Kang, J.C. The genus Cordyceps and its allies from the Kuankuoshui Reserve in Guizhou III. Fungal Divers. 2003, 14, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.Q.; Gu, D.Y.; Gu, Z.X. Cordyceps rice wine: A novel brewing process. J. Food Process Eng. 2015, 39, 581–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, C.; Jin, J.; Liu, H.; Xie, J.; Liu, P.A.; Zhang, S.H. Transcriptomic analysis of Ophiocordyceps xuefengensis stromata at different development stages. Mod. Chin. Med. 2023, 25, 523–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China. 2009. Available online: https://www.nhc.gov.cn/zwgkzt/wsbysj/200903/39591.shtml (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Food Safety and Health Supervision Bureau. Announcement on Approving 7 New Resource Foods Including Camellia Flowers (No. 1 of 2013) [Announcement]. Available online: https://www.nhc.gov.cn/wjw/c100175/201301/f8c6b8e23f1a424fa9736233bf96a108.shtml (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Choi, G.S.; Shin, Y.S.; Kim, J.E.; Ye, Y.M.; Park, H.S. Five cases of food allergy to vegetable worm (Cordyceps sinensis) showing cross-reactivity with silkworm pupae. Allergy 2010, 65, 1196–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.J.; Wei, F.; Ma, S.C. Application of ITS1 barcode sequence for the identification of Cordyceps sinensis from its counterfeit species. Chin. J. Pharm. Anal. 2015, 35, 1716–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.Y.; Zou, Y.; Zheng, Q.W.; Lu, F.X.; Li, D.H.; Guo, L.Q.; Lin, J.F. Physicochemical, functional and structural properties of the major protein fractions extracted from Cordyceps militaris fruit body. Food Res. Int. 2021, 142, 110211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, B.X.; Xue, L.N.; Wei, T.; Ye, Z.W.; Li, X.H.; Guo, L.Q.; Lin, J.F. Enhancement of ergothioneine production by discovering and regulating its metabolic pathway in Cordyceps militaris. Microb. Cell Fact. 2022, 21, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.B.; Xu, J.; Wang, S.; Hou, Z.D.; Lu, X.C.; An, L.P.; Du, P.G. A new cerebroside from cordyceps militaris with anti-PTP1B activity. Fitoterapia 2019, 138, 104342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.F.; Li, H.X.; Li, W.J.; Zhuang, S.S.; He, Y.; Zhan, X.Y.; Mei, Q.X.; Qian, Z.M. Determination of free and total sterols in four Cordyceps species by green HPLC method. Mycosystema 2022, 41, 1796–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Tian, Y.H.; Pang, D.R.; Gao, X.; Guo, Y.J.; Li, X. Research progress on chemical composition, pharmacological effects and industrialization of Cordyceps militaris. Chin. Tradit. Herbal. Drugs 2024, 55, 2413–2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.D.; Zhong, H.Q.; Wang, X.B.; Xue, L.Y. Research progress on active components of Cordyceps cicadae and their applications. Food Ind. 2025, 46, 231–237. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, Z.; Zhang, J.L.; Zhang, C.H.; Chen, X.L.; Huang, Q.J.; Huang, H.; Li, T.H.; Wang, G.Z.; Deng, W.Q. Cloning and expression analysis of small heat shock protein gene HSP30 in Tolypocladium guangdongense. Genom. Appl. Biol. 2022, 41, 1713–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.Y.; Li, T.H.; Song, B.; Huang, H. Comparison of selected chemical component levels in Cordyceps guangdongensis, C. sinensis and C. militaris. Acta Edulis Fungi 2009, 16, 54–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.Y.; Zhu, Y.J.; Zhang, D.L.; Fu, Y.N.; Hou, S.L.; Yin, L.P.; Chen, S.J. Research progress in host insects of materia medica Dongchong Xiacao. West. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2020, 33, 136–145. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, D.R.; Li, C.D.; Shu, C.; Yang, Y.X. Study on the Chinese species of the genus Hepialus and their geocraphical distribution. Acta Entomol. Sin. 1996, 39, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.F. The host insect of chinese “insect herb”, Hepialus armoricanus oberthür. Acta Entomol. Sin. 1965, 14, 620–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, E.S.; Robinson, G.S.; Wagner, D.L. Ghost-moths of the world: A global inventory and bibliography of the Exoporia (Mnesarchaeoidea and Hepialoidea) (Lepidoptera). J. Nat. Hist. 2020, 34, 823–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.W.; Liu, X.; Zhang, G.R. Revision of taxonomic system of the genus Hepialus (Lepidoptera, Hepialidae) currently adopted in China. J. Hunan Univ. Sci. Technol. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2010, 25, 114–120. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.L.; Yao, Y.J. Host insect species of Ophiocordyceps sinensis: A review. Zookeys 2011, 127, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Ye, Y.S.; Han, R.C. Fruiting body production of the medicinal Chinese caterpillar mushroom, Ophiocordyceps sinensis (Ascomycetes), in artificial medium. Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2015, 17, 1107–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.J.; Ye, M.; Zhou, Z.J.; Dai, Y.; Xiang, L. Research progress on rearing of host insects of Ophiocordyceps sinensis. Chin. Tradit. Herbal. Drugs 2009, 40, 85–87. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, N.Y.; Zhou, Z.R.; Zhang, X.C.; San, Z.; Zeng, L. Preliminary study on Ophiocordyceps sinensis. Chin. Tradit. Herbal. Drugs 1980, 11, 273–275. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.F.; Wang, Z.; Zheng, F.Y.; Lin, M.Y. Preliminary screening of feed materials for Hepialus larvae and study on its feeding habits. Fujian Agric. Sci. Technol. 2016, 4, 16–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.P.; Mu, D.D.; Chen, S.J.; Liu, L.; Wang, Z.K. The title of the article: Effects on growth and digestive enzyme activities of the Hepialus gonggaensis larvae caused by introducing probiotics. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 27, 529–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.B.; Wang, Z.; Huang, X.F.; Zheng, F.Y. Research status on biological characteritics host insects and larva feeding of Ophiocordyceps sinensis Berk. Sacc., Hepithelial Armoricanus Oberthlir. Fujian Agric. Sci. Technol. 2019, 5, 66–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Chen, S.J.; Xiao, Z.X.; Luo, S.D.W. Study on larval rearing of host insects of Ophiocordyceps sinensis in Naqu, Tibet. Chongqing J. Res. Chin. Drugs Herbs 2011, 2, 2–4. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, L. Rearing of host insects of Ophiocordyceps sinensis. Gansu Sci. Technol. 1994, 1, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.P.; He, Y.; Liu, J.M.; Xia, J.M.; Li, W.J.; Liu, X.Z. Hybrid breeding of high quality of Hepialus sp., the host of Ophiocordyceps sinensis, and prevention of the host insect reproductive degradation. Mycosystema 2016, 35, 456–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, L.; Chen, S.L.; Dai, Y.; Han, K.H.; Wang, Q.; Chen, X.P.; Zhou, Z.J.; Ye, M.; Zhou, Y.J. Study on biological characteristics of artificial breeding adults of Hepialus Xiaojinensis the larval host of Cordyceps sinensis. Mod. Tradit. Chin. Med. Mater. Medica-World Sci. Technol. 2012, 14, 1172–1176. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, D.R.; Peng, Y.Q.; Chen, J.Y.; Cao, Y.Q.; Yang, P. Advances in genus Hepialus moth of Cordyceps sinensis host. In Proceedings of the 2009 Annual Conference of Yunnan Entomological Society, Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming, China, 1 October 2009; Available online: https://cpfd.cnki.com.cn/Article/CPFDTOTAL-YNKC200909001066.htm (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Guo, L.N.; Liu, J.; Yuan, H.; Zan, K.; Zheng, J.; Ma, S.C.; Qian, Z.M.; Li, W.J. Comparative study of DNA barcoding of cultivated and natural Cordyceps sinensis. Chin. J. Pharm. Anal. 2019, 39, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, W.; Li, S.S.; Peng, Q.Y.; Zhang, G.R.; Liu, X. A real-time qPCR assay to quantify Ophiocordyceps sinensis biomass in Thitarodes larvae. J. Microbiol. 2013, 51, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ma, Q.L.; Qiao, Z.Q. Study on the isolation culture of Cordyceps sinensis (Berkeley) Saccrdo in Gansu province. Gansu Agric. Sci. Technol. 2001, 7, 43–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.Q.; Zhang, D.L.; Zeng, W.; Chen, S.J.; Yin, D.H. An experiment of infecting Hepialus larvae with Cordyceps sinensis. Edible Fungi 2010, 32, 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, Y.Q.; Zhu, H.L.; Zhang, D.L.; Chen, S.J. Different strains of Cordyceps sinensis on infectivity of host larvae. Edible Fungi China 2012, 31, 32–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Q.L.; Zhou, G.L.; Zhang, H.; Meng, Q.; Zhang, J.H.; Wang, H.T.; Miao, L.; Li, X. Obstacles and approaches in artificial cultivation of Chinese Cordyceps. Mycology 2018, 9, 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.M.; Peng, X.; Lee, K.L.D.; Tang, J.C.; Cheung, P.C.K.; Wu, J.Y. Structural characterisation and immunomodulatory property of an acidic polysaccharide from mycelial culture of Cordyceps sinensis fungus Cs-HK1. Food Chem. 2011, 125, 637–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.R.; Ye, M.L.; Wei, Y.S. A Method for Improving the Infection Rate of Ophiocordyceps sinensis host. CN201510281868.8, 28 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, X.; Liu, X.; He, J.M. A Method for Preparing Ophiocordyceps sinensis Strain Material with High Infection Activity and Infecting Larvae of Thitarodes hookeri. CN104381011B, 30 September 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.P. A Method for Artificial Cultivation of Chinese Cordyceps. CN201010604460.7, 24 December 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.Q.; Han, R.C.; Cao, L. Artificial cultivation of the Chinese Cordyceps from injected ghost moth larvae. Environ. Entomol 2019, 48, 1088–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Z.X.; Yu, J.F.; Wu, W.J.; Zhang, G.R. Molecular characterization and gene expression of apolipophorin III from the ghost moth, Thitarodes pui (Lepidoptera, Hepialidae). Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 2012, 80, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.S.; Zhong, X.; Kan, X.T.; Gu, L.; Sun, H.X.; Zhang, G.R.; Liu, X. De novo transcriptome analysis of Thitarodes jiachaensis before and after infection by the caterpillar fungus, Ophiocordyceps sinensis. Gene 2016, 580, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, J.C.; Wei, X.L.; Zheng, W.F.; Guo, W.; Liu, R.D. Species identification and component detection of Ophiocordyceps sinensis cultivated by modern industry. Mycosystema 2016, 35, 404–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Component | Category | Biological Functions | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polysaccharides | Polysaccharides | Immune modulation; tumor therapy; anti aging; endocrine regulation; improvement of athletic performance | [8,45] |

| Soluble polysaccharides | [51] | ||

| Adenosine | Nucleosides | Vasodilation, lowering of blood pressure; reduction in heart rate; other important pharmacological effects | [52] |

| Inosine | [53] | ||

| Hypoxanthine | [53] | ||

| Cholesterol | Sterols | Immune modulation; anti tumor; anti aging; enhancement of lung function; inhibition of cell proliferation | [54] |

| Ergosterol | [55] | ||

| Sitosterol | [55,56] | ||

| Cordycepin | Adenosine derivatives | Reduction in organ rejection; antibacterial; anti inflammatory; antiviral; anti tumor and immunomodulatory activities | [6,46] |

| Cordycepic acid (Mannitol) | Alcohols | Inhibition of tumors and enhancement of immunity | [57] |

| Polyphenols | Polyphenols | Strong antioxidant and potential anti cytotoxic activities | [58,59] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

He, Z.; Ye, M.; Wu, H.; Liang, D.; Huan, J.; Yao, Y.; Wu, X.; Luo, X. The Conservation Crisis of Ophiocordyceps sinensis: Strategies, Challenges, and Sustainable Future of Artificial Cultivation. J. Fungi 2025, 11, 892. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120892

He Z, Ye M, Wu H, Liang D, Huan J, Yao Y, Wu X, Luo X. The Conservation Crisis of Ophiocordyceps sinensis: Strategies, Challenges, and Sustainable Future of Artificial Cultivation. Journal of Fungi. 2025; 11(12):892. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120892

Chicago/Turabian StyleHe, Zhoujian, Meng Ye, Huaxue Wu, Dan Liang, Jie Huan, Yuan Yao, Xinyue Wu, and Xiaomei Luo. 2025. "The Conservation Crisis of Ophiocordyceps sinensis: Strategies, Challenges, and Sustainable Future of Artificial Cultivation" Journal of Fungi 11, no. 12: 892. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120892

APA StyleHe, Z., Ye, M., Wu, H., Liang, D., Huan, J., Yao, Y., Wu, X., & Luo, X. (2025). The Conservation Crisis of Ophiocordyceps sinensis: Strategies, Challenges, and Sustainable Future of Artificial Cultivation. Journal of Fungi, 11(12), 892. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120892