Abstract

Hymenochaetales, belonging to Agaricomycetes, Basidiomycota, comprises most polypores and corticioid fungi and, also, a few agarics. The latest taxonomic framework accepts 14 families in this order. When further exploring species diversity of Hymenochaetales, two corticioid specimens collected from China producing cystidia with large umbrella-shaped crystalline heads attracted our attention. This kind of cystidia was reported only in three unsequenced species, viz. Tubulicrinis corneri, T. hamatus and T. umbraculus, which were accepted in Tubulicrinaceae, Hymenochaetales. The current multilocus-based phylogeny supports that the two Chinese specimens formed an independent lineage from Tubulicrinaceae as well as the additional 13 families and all sampled genera in Hymenochaetales. Therefore, a monotypic family, Umbellaceae, is newly described with the new genus Umbellus as the type genus to represent this lineage. The two Chinese specimens are newly described as U. sinensis, which differs from T. corneri, T. hamatus, and T. umbraculus in a combination of a smooth to grandinioid hymenophoral surface, not flattened, broadly ellipsoid basidiospores with a tiny apiculus, and growth on angiosperm wood. Due to the presence of the unique cystidia, the three species of Tubulicrinis, even though they lack available molecular sequences, are transferred to Umbellus as U. corneri, U. hamatus, and U. umbraculus. Hereafter, all known species with large umbrella-shaped crystalline-headed cystidia are in a single genus. In summary, the current study provides a supplement to the latest taxonomic framework of Hymenochaetales and will help to further explore species diversity and the evolution of this fungal order.

1. Introduction

Hymenochaetales was described as a monotypic order to accommodate Hymenochaetaceae by Frey et al. [1]. This fungal order, belonging to Agaricomycetes, Basidiomycota [2], is globally distributed in the forest ecosystem, and for now comprises 14 families and 83 genera, of which 19 genera have no certain position at the family level [3]. Most of the species in Hymenochaetales are polypores and corticioid fungi, whereas certain species, like those in the genera Blasiphalia, Contumyces, and Rickenella, are agarics. In addition to the morphological diversity, various trophic modes, including saprotrophs, parasites, and symbiotes (with both tree and moss), also exist in Hymenochaetales. More importantly, some polypores of Hymenochaetales, like those in the genera Sanghuangporus and Phylloporia among others, are highly valuable medicinal fungi [4,5]. Therefore, species in Hymenochaetales can be important in the forest ecosystem and for economic development as strategic biological resources [6].

While the species diversity has been well explored all over the world [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17], the systematics of Hymenochaetales at the family level were poorly established. The families recorded in several papers were even contradictory. This phenomenon was mainly due to the samplings in phylogenetic analyses with a biased emphasis on target fungal groups [18,19] and was also caused by the unreliable phylogenetic analyses inferred only from one or two ribosomal loci [18,20]. This was the case until, recently, Wang et al. [3] systematically summarized the taxonomic background and updated the taxonomic framework of Hymenochaetales via multilocus phylogenetic analyses on the basis of the most comprehensive samplings. This update provides a crucial basis for further exploring species diversity and the taxonomic positions of species in Hymenochaetales.

The cystidium is a sterile structure but possesses unique importance in fungal taxonomy, especially for corticioid fungi that normally have simple morphological traits. Among various kinds of cystidia, large umbrella-shaped crystalline-headed cystidia are rarely present and are known only in three species, viz. Tubulicrinis corneri, T. hamatus, and T. umbraculus [21,22,23]. Tubulicrinis, typified by T. glebulosus, was placed in Tubulicrinaceae, Hymenochaetales for the first time by Larsson [20]. This opinion is accepted by Wang et al. [3], treating Tubulicrinaceae as a monotypic family. Unfortunately, the molecular sequences are unavailable from T. corneri, T. hamatus, and T. umbraculus. Therefore, the phylogenetic relationships among these three species and other species in Tubulicrinis are unknown.

When examining two corticioid specimens collected in China, umbrella-shaped crystalline-headed cystidia were observed. To identify these two specimens at a species level and determine their taxonomic position at higher ranks, careful morphological examinations and phylogenetic analyses were performed. In addition to the unique cystidia, other key taxonomic morphological characters of these two specimens were different from T. corneri, T. hamatus, and T. umbraculus. Moreover, these two specimens occupied an independent lineage from Tubulicrinaceae as well as the additional 13 families and all sampled genera in Hymenochaetales. Therefore, these two specimens are described as a new species belonging to a new genus in a new monotypic family. In addition, T. corneri, T. hamatus, and T. umbraculus are transferred to the new genus.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Morphological Examination

The two studied specimens were deposited at the Fungarium, Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (HMAS), Beijing, China.

Macromorphological characters were examined with the aid of a Leica M125 stereomicroscope (Wetzlar, Germany) at magnifications of up to 100×. Special color terms followed Petersen [24]. Micromorphological characters were examined with an Olympus BX43 light microscope (Tokyo, Japan) at magnifications of up to 1000×, following Wang et al. [25]. Specimen sections were separately mounted in Cotton Blue, Melzer’s reagent, and 5% potassium hydroxide. All measurements were made from the sections mounted in Cotton Blue. When presenting the variation in basidiospore sizes, 5% of the measurements were excluded from each end of the range and are given in parentheses. Drawings were made with the aid of a drawing tube. The following abbreviations are used in the descriptions: L = mean basidiospore length (arithmetic average of all measured basidiospores), W = mean basidiospore width (arithmetic average of all measured basidiospores), Q = variation in the L/W ratios between the studied specimens, and (n = a/b) = number of basidiospores (a) measured from given number of specimens (b).

The detailed structure of cystidia was examined with a Hitachi SU8000 scanning election microscope (Tokyo, Japan). The sections of basidiomes were sprayed with gold and platinum using Leica EM ACE600 (Wetzlar, Germany).

2.2. Molecular Sequencing

Crude DNA was extracted from basidiomes of dry specimens as templates for subsequent PCR amplifications using FH Plant DNA Kit (Beijing Demeter Biotech Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The nrSSU, ITS, nrLSU, mtSSU, and RNA polymerase II second largest subunit (RPB2) regions were amplified using the selected primer pairs PNS1/NS41 [26], ITS1F/ITS4 [27], LR0R/LR7 [28], MS1/MS2 [29], and fRPB2-5F/fRPB2-7cR [30] and bRPB2-6F/bRPB2-7.1R [31], respectively. The PCR procedures for nrSSU and mtSSU regions were as follows: initial denaturation at 94 °C for 3 min, followed by 34 cycles at 94 °C for 40 s, 55 °C for 45 s, and 72 °C for 1 min and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. For ITS region, they were as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 3 min, followed by 34 cycles at 94 °C for 40 s, 57.2 °C for 45 s, and 72 °C for 1 min and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. For nrLSU region they were as follows: initial denaturation at 94 °C for 1 min, followed by 34 cycles at 94 °C for 30 s, 47.2 °C for 1 min, and 72 °C for 1.5 min and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. And, for RPB2 region, they were as follows: initial denaturation at 94 °C for 2 min, followed by 9 cycles at 94 °C for 40 s, 60 °C for 40 s, and 72 °C for 2 min and 36 cycles at 94 °C for 45 s, 55 °C for 1.5 min, and 72 °C for 2 min, and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. With the same primers used in PCR amplifications, the PCR products were sequenced at the Beijing Genomics Institute, Beijing, China, and the resulting new sequences were deposited in GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/; accessed on 7 July 2023; Table 1).

Table 1.

Information on taxa in Agaricomycetes used in phylogenetic analyses.

2.3. Phylogenetic Analyses

In addition to the newly generated sequences for this study, additional related sequences, mainly following Wang et al. [3], were also integrated in phylogenetic analyses (Table 1).

The dataset with a combination of nrSSU, ITS, nrLSU, mtSSU, and RPB2 regions was used to explore the phylogenetic position of the newly sequenced specimens in Hymenochaetales. Within Hymenochaetales, all sequenced species with uncertain taxonomic positions at the family level and selected representatives of all 14 previously accepted families were included. Meanwhile, two species from Polyporales, viz. Fomitopsis pinicola and Grifola frondosa, were also included, and two species from Thelephorales, viz. Boletopsis leucomelaena and Thelephora ganbajun, were selected as outgroup taxa [3].

Each of the five regions was separately aligned using MAFFT v.7.110 [32] under the “G-INS-i” option [33]. Due to the crucial role of gaps for delimiting taxa at the higher taxonomic level [34], they were reserved as the fifth character for all five regions. Then, the alignments of the five regions were concatenated as a single alignment (File S1). The best-fit evolutionary models of the concatenated alignment and each single-region alignment were estimated using jModelTest v.2.1.10 [35,36] under Akaike information criterion. Maximum Likelihood (ML) and Bayesian Inference (BI) algorithms were utilized for phylogenetic analyses of the concatenated alignment, and ML algorithm was utilized for phylogenetic analyses of each single-region alignment. The ML algorithm was conducted using raxmlGUI v.8.2.12 [37] and the bootstrap (BS) replicates were calculated under the auto FC option [38]. The BI algorithm was conducted using MrBayes v.3.2.7 [39]. Two independent runs, with each run including four chains and starting from random trees, were employed. Trees were sampled every 1000th generation. Of the sampled trees, the first 25% were removed while the other 75% were retained for constructing a 50% majority consensus tree and calculating Bayesian posterior probabilities (BPPs). Chain convergence was judged using Tracer v.1.7.1 [40] after discarding 25% of samples. The final phylogenetic tree was edited and visualized using tvBOT (https://www.chiplot.online/tvbot.html; accessed on 24 June 2023) [41].

3. Results

3.1. Molecular Phylogeny

In this study, nine sequences for the five regions used in phylogenetic analyses were newly generated from the two studied specimens, viz. LWZ 20190615-27 and LWZ 20190615-39, with the absence of the mtSSU sequence from the specimen LWZ 20190615-39 (Table 1).

The phylogenies generated from the five single-region alignments under the best-fit evolutionary model of GTR + I + G generally share rather similar topologies in their main lineages (Figures S1–S5). However, in each phylogeny, several species are not located in their supposed positions and the BS values are not high enough. This phenomenon indicates that a single region cannot well delimit the taxonomic relationship of Hymenochaetales. Therefore, multilocus-based phylogenetic analyses are necessary.

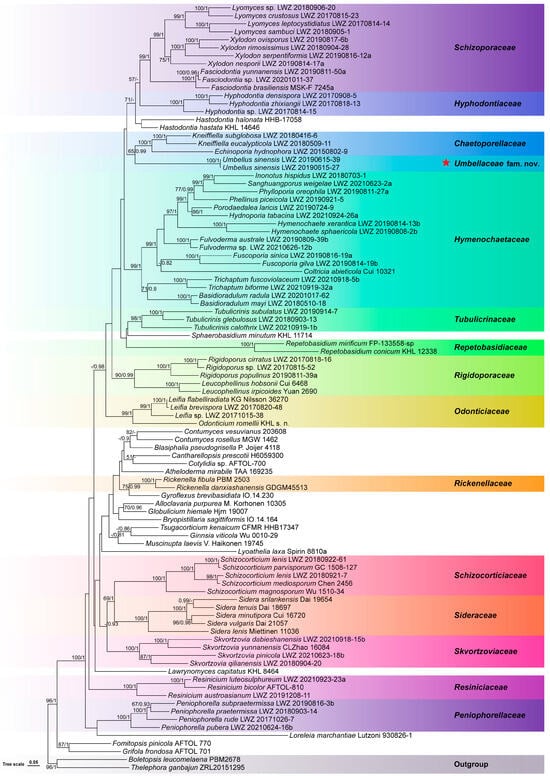

The combined dataset of nrSSU, ITS, nrLSU, mtSSU, and RPB2 regions from 96 collections generated a concatenated alignment of 5190 characters with GTR + I + G as the best-fit evolutionary model. In the ML algorithm, the BS search stopped after 150 replicates. In the BI algorithm, after 25 million generations with an average standard deviation of split frequencies of 0.008948, all chains converged, which was indicated by the effective sample sizes of all parameters being above 6600 and all potential scale reduction factors being equal to 1.000. ML and BI algorithms generated similar topologies in main lineages, and thus, the topology generated by the ML algorithm is presented along with BS values and BPPs above 50% and 0.8, respectively at the nodes (Figure 1). In this phylogeny, the monophyly of Hymenochaetales receives full statistical support, and within Hymenochaetales, the two newly sequenced specimens collected from Guangdong, China, group together as an independent lineage (BS = 100%, BPP = 1) from all sampled families and genera. Taking the unique characters of the two specimens into consideration together, we describe them as members of a new species of a new genus in a new family.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic position of Umbellaceae (marked with a red star) within Hymenochaetales, inferred from the combined dataset of nrSSU, ITS, nrLSU, mtSSU, and RPB2 regions. The topology has been generated using the maximum likelihood algorithm. The maximum likelihood bootstrap values and the Bayesian posterior probability values above 50% and 0.8, respectively are shown at the nodes. Boletopsis leucomelaena and Thelephora ganbajun from Thelephorales have been selected as outgroup taxa.

3.2. Taxonomy

Umbellaceae Xue W. Wang & L.W. Zhou, fam. nov.

MycoBank: MB 851425

Etymology: Umbellaceae (Lat.), referring to the type genus Umbellus.

Diagnosis: Distinguished from other families of Hymenochaetales by capitate cystidia with large umbrella-shaped crystalline heads.

Type genus: Umbellus Xue W. Wang & L.W. Zhou.

Type species: Umbellus sinensis Xue W. Wang & L.W. Zhou.

Description: Basidiomes annual, adnate and resupinate. Hymenophore smooth to grandinioid or odontioid to hydnoid, white to cream; margin thinning out, arachnoid, concolorous or paler than subiculum. Hyphal system monomitic; generative hyphae with clamp connections. Cystidia dimorphic: (1) arising from subhymenium and more or less enclosed in the hymenium or strongly projecting for the greater part of their length, cylindrical, unevenly thick-walled with a narrow or wide lumen, rooted at the base, gradually tapering, broadly rounded at the apex and covered by a large umbrella-shaped crystalline head; (2) originating laterally on subicular hyphae, with the same morphology as those arising from subhymenium but smaller in size and stalk slightly thick-walled. Basidia subclavate to clavate-cylindrical, barrel-shaped or suburniform, with a basal clamp connection and four sterigmata. Basidiospores oblong-ellipsoid or broadly ellipsoid, hyaline, smooth, thin-walled, indextrinoid, inamyloid, acyanophilous.

Notes: Morphologically, the monotypic family Umbellaceae resembles Chaetoporellaceae, Hyphodontiaceae, and Schizoporaceae due to its resupinate basidiomes and light-colored hymenophoral surface, but differs in having capitate cystidia with large umbrella-shaped crystalline heads [3].

Umbellus Xue W. Wang & L.W. Zhou, gen. nov.

MycoBank: MB 851426

Etymology: Umbellus (Lat.), referring to the large umbrella-shaped crystalline head of cystidia.

Diagnosis: Distinguished by capitate cystidia with a large umbrella-shaped crystalline head.

Type: Umbellus sinensis Xue W. Wang & L.W. Zhou.

Description: Basidiomes annual, adnate and resupinate. Hymenophore smooth to grandinioid or odontioid to hydnoid, white to cream; margin thinning out, arachnoid, concolorous or paler than subiculum. Hyphal system monomitic; generative hyphae with clamp connections. Cystidia dimorphic: (1) arising from subhymenium and more or less enclosed in the hymenium or strongly projecting for the greater part of their length, cylindrical, unevenly thick-walled with a narrow or wide lumen, rooted at the base, gradually tapering, broadly rounded at the apex and covered by a large umbrella-shaped crystalline head; (2) originating laterally on subicular hyphae with the same morphology as those arising from subhymenium but smaller in size and stalk slightly thick-walled. Basidia subclavate to clavate-cylindrical, barrel-shaped or suburniform, with a basal clamp connection and four sterigmata. Basidiospores oblong-ellipsoid or broadly ellipsoid, hyaline, smooth, thin-walled, indextrinoid, inamyloid, acyanophilous.

Notes: The two studied specimens, described as Umbellus sinensis below, are distinguished by the capitate cystidia with umbrella-shaped crystalline heads. Previously, three species of Tubulicrinis, viz. T. corneri, T. hamatus, and T. umbraculus, were reported to have this kind of cystidium [21,22,23]. In the current phylogeny, the lineage formed by the two studied specimens is separated from Tubulicrinis (Figure 1). Therefore, they cannot be placed in Tubulicrinis. In addition, while T. corneri was originally described in Tubulicrinis [21], the basionyms of T. hamatus and T. umbraculus belong to Peniophora [22,23]. Peniophora is a genus accepted in Russulales and thus cannot accommodate the two studied specimens. Therefore, a new genus, Umbellus, is introduced to accommodate species with the unique cystidia. Previously, the three species with the large umbrella-shaped crystalline-headed cystidia were all placed in the same genus, Tubulicrinis. For now, the fourth species with this kind of cystidium has been phylogenetically proven in a new genus, Umbellus. Therefore, although the molecular sequences of T. corneri, T. hamatus, and T. umbraculus are unavailable for phylogenetic analyses, these three species are transferred to Umbellus on the basis of their unique cystidia that hereafter are only known in this genus.

Umbellus corneri (Jülich) Xue W. Wang & L.W. Zhou, comb. nov.

MycoBank: MB 851427

Basionym:Tubulicrinis corneri Jülich, Persoonia 10(3): 332 (1979).

Umbellus hamatus (H.S. Jacks. & Donk) Xue W. Wang & L.W. Zhou, comb. nov.

MycoBank: MB 851428

Basionym: Peniophora hamata H.S. Jacks., Canadian Journal of Research, Section C 26: 133 (1948).

≡ Tubulicrinis hamatus (H.S. Jacks.) Donk [as ‘hamata’], Fungus, Wageningen 26 (1–4): 14 (1956).

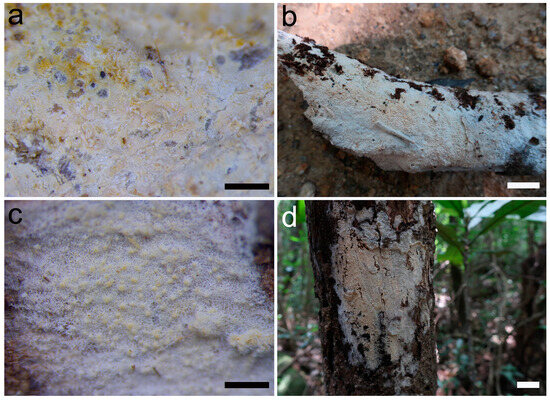

Figure 2.

Basidiomes of Umbellus sinensis. (a,b) LWZ 20190615-27 (holotype). (c,d) LWZ 20190615-39 (paratype). Scale bars: (a,c) = 0.1 mm, (b,d) = 1 cm.

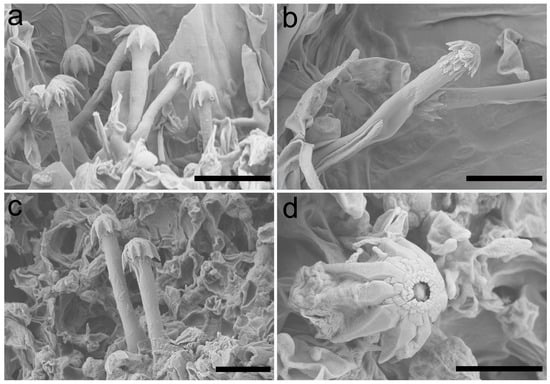

Figure 3.

Scanning electron micrograph of cystidia of Umbellus sinensis. (a,b) LWZ 20190615-27 (holotype). (c,d) LWZ 20190615-39 (paratype). Scale bars: (a–c) = 10 μm, (d) = 5 μm.

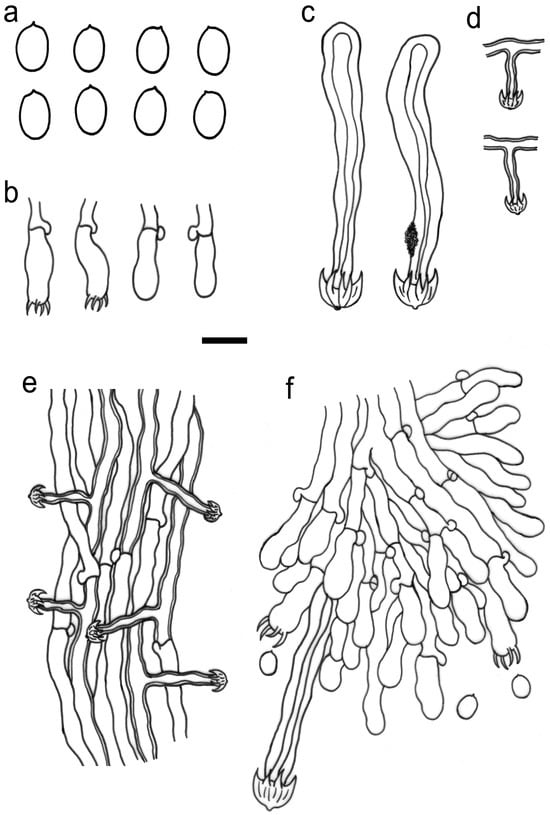

Figure 4.

Microscopic structures of Umbellus sinensis (drawn from LWZ 20190615-27, holotype). (a) Basidiospores. (b) Basidia and basidioles. (c) Cystidia from the subhymenium. (d) Cystidia from subiculum. (e) Hyphae from subiculum. (f) A vertical section through hymenium. Scale bar: for (a) = 5 μm; for (b–f) = 10 μm.

MycoBank: MB 851429

Etymology: sinensis (Lat.), referring to the type locality China.

Diagnosis: Distinguished by smooth to grandinioid hymenophoral surface and not flattened, broadly ellipsoid basidiospores with a tiny apiculus.

Type: China, Guangdong Province, Huizhou, Boluo County, Xiangtoushan National Nature Reserve, on a fallen branch of an angiosperm, 15 June 2019, Li-Wei Zhou, LWZ 20190615-27 (Holotype in HMAS).

Description: Basidiomes annual, adnate and resupinate, easily cracked when dry. Hymenophore smooth to grandinioid, white to cream; margin thinning out, arachnoid, paler than subiculum. Hyphal system monomitic; generative hyphae with clamp connections. Subicular hyphae hyaline, branched, 4–5.5 µm in diam, thin- to slightly thick-walled. Subhymenial hyphae hyaline, thin-walled, 4–4.5 µm in diam. Cystidia dimorphic: (1) arising from subhymenium and strongly projecting out for the greater part of their length, cylindrical, 45–60 × 6.5–9.5 µm, unevenly thick-walled with a lumen up to 4 µm, with a narrow or wide lumen, rooted at the base, gradually tapering, broadly rounded at the apex and covered by a large umbrella-shaped crystalline head of up to 9 µm in diam, set with 10–12 deflexed and radiating ridges terminating in acute spines; (2) originating laterally on subicular hyphae with the same shape as those arising from subhymenium but smaller in size, 15–25 × 1.5–3.5 µm, with an umbrella-shaped crystalline head of 5–6 µm in diam, stalk slightly thick-walled. Basidia subclavate to barrel-shaped, with a basal clamp connection and four sterigmata, 15–17 × 5–7 µm. Basidiospores broadly ellipsoid, hyaline, smooth, thin-walled, inamyloid, indextrinoid, acyanophilous, 4.5–5(–5.1) × (3.2–)3.3–4.2(–4.3) µm, L = 4.80 µm, W = 3.47 µm, Q = 1.37–1.38 (n = 60/2).

Additional specimen examined: China, Guangdong Province, Huizhou, Boluo County, Xiangtoushan National Nature Reserve, on a fallen branch of an angiosperm, 15 June 2019, Li-Wei Zhou, LWZ 20190615-39 (Paratype in HMAS).

Notes. Compared with Umbellus sinensis, U. corneri differs in its odontioid to slightly hydnoid hymenophoral surface [21]; U. hamatus differs in the flattened on one side, larger basidiospores (5.5–7.5 × 4–4.5 µm) with a prominent lateral apiculus [23]; and U. umbraculus (transferred below) differs in obovate, flattened-on-one-side, longer basidiospores (5–6 µm in length) [22]. Noteworthily, U. hamatus is known only on coniferous wood [23], while the other three species of Umbellus grow on angiosperm wood [21,22].

Umbellus umbraculus (G. Cunn.) Xue W. Wang & L.W. Zhou, comb. nov.

MycoBank: MB 851430

Basionym. Peniophora umbracula G. Cunn., Trans. Roy. Soc. N.Z. 83: 291 (1955).

≡ Tubulicrinis umbraculus (G. Cunn.) G. Cunn. [as ‘umbracula’], Bull. N.Z. Dept. Sci. Industr. Res. 145: 142 (1963)

A key to all four known species in Umbellus

- 1 Hymenophore odontioid or slightly hydnoid..........................................................U. corneri

- 1 Hymenophore smooth to grandinioid....................................................................................2

- 2 Basidiospores oblong-ellipsoid or obovate.......................................................U. umbraculus

- 2 Basidiospores broadly ellipsoid...............................................................................................3

- 3 Basidiospores flattened on one side, with a prominent lateral apiculus, 5.5–7.5 × 4–4.5 µm; on coniferous wood..............................................................................................U. hamatus

- 3 Basidiospores not flattened, with a tiny apiculus, 4.5–5 × 3.3–4.2 µm; on angiosperm wood...............................................................................................................................U. sinensis

4. Discussion

In this paper, the latest taxonomic framework of Hymenochaetales, proposed by Wang et al. [3], is supplemented by describing a new family, Umbellaceae. Although Umbellaceae is a monotypic family with the new genus Umbellus as the type genus, it occupies an independent phylogenetic position from all sampled families and genera in Hymenochaetales (Figure 1). Similarly, Chaetoporellaceae was also a monotypic family in Hymenochaetales when being reinstated; however, later study soon added one more genus to this family [3]. Therefore, it is reasonable to describe monotypic families to provide certain taxonomic positions at the family level for as many genera as possible, as if the phylogenetic evidence is solid. More importantly, the large umbrella-shaped crystalline-headed cystidia in Umbellaceae are unique in all fungal groups to our knowledge. In addition to the presence of unique cystidia, Umbellaceae also differs from Tubulicrinaceae in its lack of cylindrical, conical, multi-radicate cystidia with a capitate or subulate apex [3]. Therefore, the description of Umbellaceae is supported from both phylogenetic and morphological perspectives.

In the molecular era of fungal taxonomy, the generic position of a species can be easily determined using accurate molecular phylogenetic analyses [42]. Therefore, the transfer of a fungal species to another genus normally needs molecular evidence. However, in the current case, Umbellus corneri, U. hamatus, and U. umbraculus are rather old species, and we cannot sequence them now and in the foreseeable future. Moreover, the large umbrella-shaped crystalline heads of cystidia are an extremely unique morphological character in taxonomy, and could be tentatively considered to be synapomorphy. In addition to sharing the unique cystidia, Umbellus corneri, U. hamatus, and U. umbraculus also resemble U. sinensis in annual, adnate, resupinate basidiomes and a monomitic hyphal system with clamp-connected generative hyphae. Therefore, we transfer these species to Umbellus based on the morphological perspective, even though their molecular sequences are unavailable. Then, all known species with the unique cystidia are in a single genus.

After the description of Umbellaceae and Umbellus, a total of 15 families accommodating 65 genera are accepted in Hymenochaetales while an additional 19 genera in Hymenochaetales have no certain taxonomic positions at the family level [3]. The species diversity in most of these 19 genera has rarely been systematically explored with the aid of molecular evidence [43,44], and their morphological and phylogenetic relationships with the 15 known families have still not been resolved [3]. Therefore, it is too mature to assign them to any known or new families. Given above, the taxonomic framework of Hymenochaetales still needs to be further updated.

5. Conclusions

In summary, two Chinese corticioid specimens are newly described as Umbellus sinensis, and a new monotypic family Umbellaceae, typified by a new genus, Umbellus, is described to accommodate the new species in Hymenochaetales. Moreover, three combinations, viz. Umbellus corneri, U. hamatus, and U. umbraculus, are proposed for the species previously belonging to Tubulicrinis. The updated taxonomic framework of Hymenochaetales will help further explore species diversity and the evolution of this fungal order, which are the main aims of fungal taxonomy [45].

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jof10010022/s1, File S1: The concatenated alignment of nrSSU, ITS, nrLSU, mtSSU, and RPB2 regions. Figure S1: Phylogenetic relationship within Hymenochaetales, inferred from the nrSSU region. Figure S2: Phylogenetic relationship within Hymenochaetales, inferred from the ITS region. Figure S3: Phylogenetic relationship within Hymenochaetales, inferred from the nrLSU region. Figure S4: Phylogenetic relationship within Hymenochaetales, inferred from the mtSSU region. Figure S5: Phylogenetic relationship within Hymenochaetales, inferred from the RPB2 region.

Author Contributions

X.-W.W. made morphological examinations and performed molecular sequencing and phylogenetic analyses. L.-W.Z. conceived and supervised the work. X.-W.W. and L.-W.Z. wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was financed by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2022YFC2601200) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 31970012 and 32111530245).

Data Availability Statement

All sequence data generated for this study can be accessed via GenBank: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/ (accessed on 7 July 2023).

Acknowledgments

Yu-Cheng Dai (Beijing Forestry University), Zhu-Liang Yang (Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences), and Shi-Liang Liu (Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences) are thanked for their helpful discussion on the morphology of the large umbrella-shaped crystalline headed cystidia.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Frey, W.; Hurka, K.; Oberwinkler, F. Beiträge zur Biologie der Niederen Pflanzen. Systematik, Stammesgeschichte, Ökologie; Gustav Fischer Verlag: Stuttgart, Germany; New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- James, T.Y.; Stajich, J.E.; Hittinger, C.T.; Rokas, A. Toward a fully resolved fungal tree of life. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 74, 29–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.W.; Liu, S.L.; Zhou, L.W. An updated taxonomic framework of Hymenochaetales (Agaricomycetes, Basidiomycota). Mycosphere 2023, 14, 452–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.W.; Ghobad-Nejhad, M.; Tian, X.M.; Wang, Y.F.; Wu, F. Current status of ‘Sanghuang’ as a group of medicinal mushrooms and their perspective in industry development. Food Rev. Int. 2022, 38, 589–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Zhou, L.J.; Jiang, J.H.; Tian, X.M.; Zhou, L.W. Phylloporia (Hymenochaetales, Basidiomycota), a medicinal wood-inhabiting fungal genus with much potential for commercial development. Food Rev. Int. 2023, 39, 2776–2789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, M.; Zhou, L.W.; Tong, Y.J.; Yin, F. Risk assessment and warning system for strategic biological resources in China. Innov. Life 2023, 1, 100004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmasto, E. Hymenochaetoid fungi (Basidiomycota) of North America. Mycotaxon 2001, 81, 107–176. [Google Scholar]

- Arras, L.; Piga, A.; Bernicchia, A.; Gorjon, S.P. Fibricium gloeocystidiatum (Polyporales, Basidiomycetes), new to Europe. Mycotaxon 2007, 100, 343–347. [Google Scholar]

- Telleria, M.T.; Melo, I.; Dueñas, M. Resinicium aculeatum, a new species of corticiaceous fungi from Equatorial Guinea. Nova Hedwig. 2008, 87, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmasto, E.; Saar, I.; Larsson, E.; Rummo, S. Phylogenetic taxonomy of Hymenochaete and related genera (Hymenochaetales). Mycol. Prog. 2014, 13, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miettinen, O.; Larsson, K.H.; Spirin, V. Hydnoporia, an older name for Pseudochaete and Hymenochaetopsis, and typification of the genus Hymenochaete (Hymenochaetales, Basidiomycota). Fungal Syst. Evol. 2019, 4, 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, N.; Singh, A.P.; Dhingra, G.S. Hymenochaete longisterigmata sp. nov. from India. Mycotaxon 2020, 135, 631–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maubet, Y.; Campi, M.; Robledo, G. Hymenochaetaceae from Paraguay: Revision of the family and new records. Curr. Res. Environ. Appl. Mycol. (J. Fungal Biol.) 2020, 10, 242–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurchenko, E.; Riebesehl, J.; Langer, E. Fasciodontia gen. nov. (Hymenochaetales, Basidiomycota) and the taxonomic status of Deviodontia. Mycol. Prog. 2020, 19, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossmann, T.; Costa-Rezende, D.H.; Góes-Neto, A.; Drechsler-Santos, E.R. A new and threatened species of Trichaptum (Basidiomycota, Hymenochaetales) from urban mangroves of Santa Catarina Island, Southern Brazil. Phytotaxa 2021, 482, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viner, I.; Bortnikov, F.; Ryvarden, L.; Miettinen, O. On six African species of Lyomyces and Xylodon. Fungal Syst. Evol. 2021, 8, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, V.X.; de Oliveira, V.R.T.; de Lima-Junior, N.C.; de Oliveira-Filho, J.R.C.; Santos, C.; Lima, N.; Gibertoni, T.B. Taxonomy and phylogenetic analysis reveal one new genus and three new species in Inonotus s.l. (Hymenochaetaceae) from Brazil. Cryptogam. Mycol. 2022, 43, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Zmitrovich, I.V.; Malysheva, V.F. Studies on Oxyporus. I. Segregation of Emmia and general topology of phylogenetic tree. Mikol. I Fitopatol. 2014, 48, 161–171. [Google Scholar]

- Ariyawansa, H.A.; Hyde, K.D.; Jayasiri, S.C.; Buyck, B.; Chethana, K.W.T.; Dai, D.Q.; Dai, Y.C.; Daranagama, D.A.; Jayawardena, R.S.; Lücking, R.; et al. Fungal Diversity notes 111–252–taxonomic and phylogenetic contributions to fungal taxa. Fungal Divers. 2015, 75, 27–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, K.H. Re-thinking the classification of corticioid fungi. Mycol. Res. 2007, 111, 1040–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jülich, W. Studies in resupinate basidiomycetes-VI. Persoonia 1979, 10, 325–336. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, G.H. Thelephoraceae of New Zealand. Part VI. The genus Peniophora. Trans. R. Soc. N. Z. 1955, 83, 247–293. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, H.S. Studies of Canadian Thelephoraceae. I. Some new species of Peniophora. Can. J. Res. 1948, 26, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, J.H. Farvekort. In The Danish Mycological Society’s Colour-Chart; Foreningen til Svampekundskabens Fremme: Greve, Denmark, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.W.; Jiang, J.H.; Zhou, L.W. Basidioradulum mayi and B. tasmanicum spp. nov. (Hymenochaetales, Basidiomycota) from both sides of Bass Strait, Australia. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hibbett, D.S. Phylogenetic evidence for horizontal transmission of group I introns in the nuclear ribosomal DNA of mushroom-forming fungi. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1996, 13, 903–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardes, M.; Bruns, T.D. ITS primers with enhanced specifity for Basidiomycetes: Application to identification of mycorrhizae and rusts. Mol. Ecol. 1993, 2, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilgalys, R.; Hester, M. Rapid genetic identification and mapping of enzymatically amplified ribosomal DNA from several Cryptococcus species. J. Bacteriol. 1990, 172, 4238–4246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, T.J.; Bruns, T.D.; Lee, S.B.; Taylor, J.W. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications; Innis, M.A., Gelfand, D.H., Sninsky, J.J., White, T.J., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1990; pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.J.; Whelen, S.; Hall, B.D. Phylogenetic relationships among Ascomycetes: Evidence from an RNA polymerse II subunit. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1999, 16, 1799–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matheny, P.B. Improving phylogenetic inference of mushrooms with RPB1 and RPB2 nucleotide sequences (Inocybe; Agaricales). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2005, 35, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Standley, D.M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: Improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Kuma, K.; Toh, H.; Miyata, T. MAFFT version 5: Improvement in accuracy of multiple sequence alignment. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessimoz, C.; Gil, M. Phylogenetic assessment of alignments reveals neglected tree signal in gaps. Genome Biol. 2010, 11, R37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guindon, S.; Gascuel, O. A simple, fast and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst. Biol. 2003, 52, 696–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darriba, D.; Taboada, G.L.; Doallo, R.; Posada, D. jModelTest 2: More models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stamatakis, A. RAxML version 8: A tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 1312–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pattengale, N.D.; Alipour, M.; Bininda-Emonds, O.R.P.; Moret, B.M.E.; Stamatakis, A. How many bootstrap replicates are necessary? J. Comput. Biol. 2010, 17, 337–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronquist, F.; Teslenko, M.; van der Mark, P.; Ayres, D.L.; Darling, A.; Höhna, S.; Larget, B.; Liu, L.; Suchard, M.A.; Huelsenbeck, J.P. MrBayes 3.2 efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 2012, 61, 539–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambaut, A.; Drummond, A.J.; Xie, D.; Baele, G.; Suchard, M.A. Posterior summarisation in Bayesian phylogenetics using Tracer 1.7. Syst. Biol. 2018, 67, 901–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.M.; Chen, Y.R.; Cai, G.J.; Cai, R.L.; Hu, Z.; Wang, H. Tree Visualization By One Table (tvBOT): A web application for visualizing, modifying and annotating phylogenetic trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, 587–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Liu, S.L.; Zhou, L.W. Taxonomy of Hyphodermella: A case study to show that simple phylogenies cannot always accurately place species in appropriate genera. IMA Fungus 2023, 14, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redhead, S.A.; Moncalvo, J.M.; Vilgalys, R.; Lutzoni, F. Phylogeny of agarics: Partial systematics solutions for bryophilous omphalinoid agarics outside of the Agaricales (euagarics). Mycotaxon 2002, 82, 151–168. [Google Scholar]

- Nakasone, K.K., Jr.; Burdsall, H.H. Tsugacorticium kenaicum (Hymenochaetales, Basidiomycota), a new corticioid genus and species from Alaska. N. Am. Fungi 2012, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zhou, L.W.; May, T.W. Fungal taxonomy: Current status and research agendas for the interdisciplinary and globalisation era. Mycology 2023, 14, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).