Abstract

(1) Background: Heart failure (HF) represents a public health problem due to its high morbidity and mortality, increased consumption of health resources, prolonged hospitalization, and frequent readmissions. This study was conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of a nursing educational intervention using home visits (HV) combined with telephone contact in reducing hospital readmission and the mortality of patients with HF. (2) Methods: This is systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs). The databases used were CINAHL, Cochrane, PubMed and SciELO. A gray literature search included Google Scholar, OpenThesis, Clinical trials and reference lists of eligible studies. RCTs of patients diagnosed with HF were included, distributed between the control group (CG) and intervention (IG), in which the IG was submitted to the nursing intervention with HV and telephone contact in association and analyzed the result of readmission and mortality. (3) Results: The search resulted in 2528 articles and, after following steps, 11 remained for final analysis. A total of 1417 patients were analyzed and distributed: 683 in the IG and 734 in the CG. As a primary outcome, the meta-analysis identified a 36% reduction in the risk of readmission [RR 0.64, 95% CI, 0.54–0.75, p < 0.01] and a 35% reduction in mortality in the IG [RR 0.65, 95% CI, 0.50–0.85, p < 0.01]. Heterogeneity was moderate for readmission and homogeneous for mortality. (4) Conclusions: HV and telephone contact are an effective intervention strategy for nurses’ educational practice.

1. Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is a complex clinical syndrome characterized by structural and functional cardiac abnormalities that impairs ventricular function of storing or ejecting blood [1]. The disease affects a significant number of people in the world and represents a public health problem due to its high morbidity and mortality (approximately 17 million deaths), increased consumption of health resources, prolonged hospitalization, and frequent readmissions [2].

Constant hospital readmissions have been associated with decompensation of the disease, which results from exacerbation of the signs and symptoms triggered by cardiovascular or non-cardiovascular factors [3]. Therefore, HF management programs constitute a patient care approach to improve adherence to the proposed therapeutic regimen [4].

Outpatient care provided by nurses to patients with HF has been the focus of studies, showing a reduction in hospital readmissions, whether it is performed on a technical (performing health procedures), educational (guidance on self-care) or managerial (referral to complementary health services) [5]. A multidisciplinary team is highly recommended for long-term follow-up of patients with HF, but each country will provide assistance according to its local health system. However, if multidisciplinary monitoring is not possible, the participation of nurses is indicated [6].

Supportive care recommendations of previous studies suggest the use of home visits (HV) between 7–14 days after hospital discharge, with assessment performed by health professionals [2,7]. This educational strategy was tested and has a proven impact in reducing morbidity and mortality [8]. However, some situations may limit the use of HV, such as territorial extension, ability to access the location of the patient, and reduced financial resources [1]. In parallel, telephone monitoring is used as an adjuvant method of follow-up, and data from Azeka and collaborators indicate the efficiency of telephone follow-up when recording data of decreased need emergency care and re-hospitalization and death. However, when it occurs in isolation, lower results are identified when compared to HV [9].

From this perspective, it remains unclear whether the association of different nursing interventions, such as home visits and telemonitoring, may provide better clinical results than a singular intervention [1,5,6]. Furthermore, there is no systematic review in the literature to evidence this hypothesis. Given the limitations regarding the use of one technique or the other, a systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of a nursing educational intervention using home visits combined with telephone contact in reducing hospital readmission and the mortality of patients with HF, compared to those accompanied by regular health service care, without the combined intervention.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Type of Study

This was a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCT) performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) recommendations. The systematic review protocol is registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) CRD42018105760.

2.2. Search Strategy and Eligibility Criteria

The review was conducted to answer the research question: “Does the educational intervention provided by a nurse reduce the readmission or the mortality of patients with heart failure?” The PICOS strategy (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, Study) was used in the following manner: (P) patients diagnosed with HF, (I) educational intervention provided by nurses, (C) comparison with patients without the intervention, (O) primary outcome of readmission, secondary outcome of mortality, and (S) RCT.

The inclusion criteria were: (i) RCT; (ii) patients diagnosed with HF, both clinically and by complementary exams; (iii) at least two groups: control group (CG) and intervention group (IG); (iv) patients from IG receiving a nursing intervention combining HV and telephone contact; (v) outcome variables of readmission or mortality.

The excluded studies included: (i) articles not available in their entirety, even after contacting the authors; (ii) articles in which other health professionals provided the intervention; (iii) an elective outpatient allocation of participants in conditions of clinical stability; (iv) reviews, letters, conference abstracts, editorials, case reports, case series studies, and guidelines. No restriction on language or year of publication was applied.

Detailed search strategies for each of the following bibliographic databases were developed: PubMed/MEDLINE, CINAHL, SciELO and Cochrane. The database search strategies can be found in Appendix A Table A1. A gray literature search included Google Scholar, OpenThesis, and clinical trials. The Google Scholar search was limited to the first 100 most relevant articles published in the last 10 years. The reference lists of all eligible studies and reviews followed the same inclusion steps. Both the gray literature searches and electronic database searches were conducted from their coverage starting date to 7 January 2021. The results obtained were exported to Microsoft Excel™ software version 16.0, with a manual removal of duplicates. Finally, a database was generated with the titles of the articles to be analyzed.

2.3. Data Collection

Article selection occurred in two phases. In the first, the titles and abstracts of the articles were analyzed by two researchers (C.R. and Y.A.) in an independent and paired manner. Subsequently, agreement was verified between the examiners regarding the classified references, using the Kappa statistical test. The test defined agreement as low (<0.40), good (0.40–0.75) and excellent (>0.75) [10]. Good or excellent agreement was defined to enable follow-up of the steps. Otherwise, reviewers would have to undergo new training on the subject and eligibility criteria.

When the ideal level of agreement was not obtained, a third reviewer (A.F.M.) was tasked to resolve the issue. The titles and abstracts that met the eligibility criteria were maintained for the second phase. In the second phase, these eligible studies were read in their entirety. The selection system followed the previous step for final decision, and those that were not selected, after discussion, were separately recorded, along with the reason for exclusion. A standardized spreadsheet was developed for data extraction, including the following information from the studies: author(s); year of publication; country; sample of CG and IG; age group; sex; nursing intervention used; follow-up period; number of readmissions; mortality; other main findings; and study limitations. There was no analysis separated by subgroup.

The risk of bias in the included articles was assessed by two independent reviewers (C.R. and Y.A.) using the Cochrane Collaboration’s ROB tool for RCTs and disagreements were resolved by consensus or by a third reviewer (A.F.M.). The risk of bias for each item was individually classified as low, unclear, or high, according to established criteria [11].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

A forest plot was used to present the effect sizes and 95% confidence intervals. A two-tailed p-value <0.05 was used to determine significance. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed by Cochran’s Q test, and quantified by the I2 index. The Cochran Q statistic was used to evaluate the heterogeneity of the studies included in the meta-analysis, and p = 0.100 indicated significant heterogeneity. The I2 test was used to evaluate the consistency of the effects in studies in which a zero value indicated lack of heterogeneity, I2 ≤ 25% indicated low heterogeneity, 25–75% indicated moderate heterogeneity, and ≥75% indicated high heterogeneity. The relative risk (RR) with a 95% CI was calculated for dichotomous outcomes (occurrence of readmission or mortality or lack of occurrence). For results with high or moderate heterogeneity between studies, sensitivity analysis was performed to explore the effect of each individual study on the combined global estimate. In this way, the RR of studies with a low risk of bias to hide the allocation were analyzed and presented in a forest plot. The analysis was performed using the Review Manager, version 5.3 (Cochrane IMS).

3. Results

3.1. Included Studies

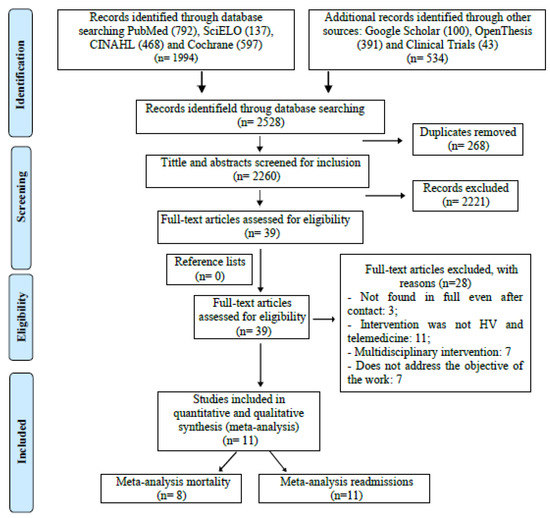

The process of identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion is depicted in the PRISMA flowchart (Figure 1). A total of 2528 studies were identified. Of these, 268 studies were duplicates, 2221 studies were excluded based on titles and abstracts, and 28 studies were excluded after screened the full text versions. Thus, 11 articles were selected for this review [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. The kappa test was applied in the first stage of selection, reaching a level of 0.63, which is considered good for continuity of the following stages.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram. PRISMA flow diagram showing study identification, selection, eligibility, and inclusion. Eleven articles were selected for this review. HV: Home Visit.

3.2. Study Characteristics

The selected articles were published between 2001 and 2019. A total of 1417 patients were analyzed, with 683 in IGs and 734 in CGs. Male participants (56%) and a mean age of 72 years prevailed in IG. CG had a higher participation of men (55%), and a mean age of 74. A summary of the descriptive characteristics of the included articles is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Main characteristics of the studies eligible for analysis.

Table 2.

Strategies intervention versus control.

The quantity and frequency of home evaluation varied among studies. A total of 73% (n = 8) of the analyzed articles revealed the total number of HV performed, ranging from one to nine, with a mean of four visits. The frequency of visits was not established a priori, as it was influenced by the clinical presentation of the patient post-discharge. The ideal duration of follow-up and the number of visits per year have not been clearly defined and are likely to depend on the patient and clinical characteristics.

Telephone intervention was used as a complementary method to HV in all 11 studies. As for HV, some variation was identified in the number of assessments and the time between each telephone contact. Some authors [16,17,18,19,20,21,22] provided the number of calls made to patients, with a range of 4–18, and a mean of 9 within the follow-up period. The ideal number of telephone consultations and the duration of each call were not defined in this study.

The readmission and mortality results were the primary outcomes analyzed in this review and are shown in Table 1. Different authors evaluated the impact of educational interventions on QoL [16,17,18,21,22], knowledge of the disease [20,22], self-care [17,20,22], costs of readmission for HF [12,19], and the cost-effectiveness ratio of the intervention [12]. The comparison of results between groups in each study is shown in Table 1.

3.3. Risk of Bias

In the risk of bias analysis, the kappa coefficient between the two reviewers was considered excellent (0.81). Appendix A Table A2 shows the bias risk analysis for each selected study.

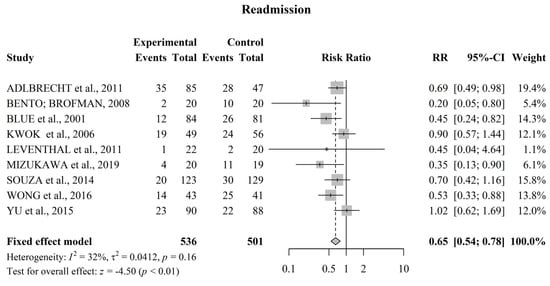

3.4. Meta-Analysis for Readmission

Figure 2 shows a meta-analysis of the effectiveness of nursing interventions on reducing readmissions in patients with HF. IG presented a lower number of readmissions in the follow-up period compared to CG (155 vs. 245, respectively), except in two studies [12,16]. Moderate heterogeneity was detected among studies (I2 = 39%). The meta-analysis indicated that the proposed educational intervention reduced the risk of readmission by 36% when compared to usual care [RR 0.64, 95% CI, 0.54–0.75, p < 0.01].

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the effect of educational nursing interventions on reducing readmissions in patients with HF. The meta-analysis identified a 36% reduction in the risk of readmission [RR 0.64, 95% CI, 0.54−0.75, p < 0.01]. CI = confidence interval; RR = relative risk. References involved in the study: [12,13,14,15,16,17,20,21,22].

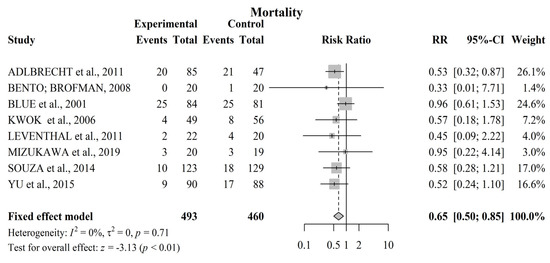

3.5. Meta-Analysis for Mortality

Figure 3 shows a meta-analysis of the effectiveness of nursing interventions on reducing the mortality of patients with HF. In this analysis, eight studies presented mortality data [12,13,14,16,17,20,22]. A total of 953 patients participated in the studies that investigated this outcome. Of these participants, IG shows a lower number of deaths in the follow-up period compared to CG (73 vs. 97, respectively), except in tow studies [14,17] in which an equal value was noted between groups. The risk of bias analysis using the Q test expressed by I2 indicates that the studies were homogeneous (0%) with regard to their methodological process. The meta-analysis indicates that patients with nursing follow-up supported by a pre-established educational intervention had a 35% lower risk of death when compared to those treated with routine care [RR 0.65, 95% CI, 0.50–0.85, p < 0.01].

Figure 3.

Forest plot of the effect of educational nursing interventions on reducing mortality in patients with HF. The meta-analysis identified a 35% reduction in mortality in the IG [RR 0.65, 95% CI, 0.50−0.85. References involved in the study: [12,13,14,15,16,17,20,22].

4. Discussion

The main findings of this systematic review and meta-analysis include: (1) educational intervention by nurses, from home visits combined with telephone contact, reduced the chance of readmission by 36% compared to the usual care group; and (2) IG patients showed a 35% reduction in the risk of death when compared to those in CG.

The results of our study are similar to the results of systematic reviews previously published, indicating a lower rate of readmission or mortality in individuals with HF followed by nurses after hospital discharge [23,24]. A meta-analysis carried out by Van Spall and colleagues [23], which included 53 RCT studies, showed 22% less risk of death [RR 0.78, 95% CI, 0.62–0.98] and 35% readmission for all causes [RR 0.65, 95% CI, 0.49–0.86] in IG patients followed by nurses with RV compared to CG with usual care. Slyer and collaborators [24] evaluated studies published until July 2010 in their meta-analysis. They show that the transition from health care intervention by HV and telephone contact led by a nurse can reduce the rate of readmission of patients with heart failure. However, the results were not statistically significant (RR 0.80, 95% CI, 0.66–0.96 and RR 1.06, 95% CI, 0.95–1.19, respectively).

As of today, there is no other known method than meta-analysis that has assessed the impact of nursing intervention with home visits associated with telephone consultations after hospital discharge of patients with HF on readmission or mortality rates. In addition to the primary outcomes mentioned above, our review incorporates evidence from different authors who assessed the impact of educational interventions on QoL, knowledge of the disease, self-care, readmission costs for HF and the cost-effectiveness of the intervention.

Non-adherence to established therapy for symptom control, in addition to sudden clinical changes generated by the disease, require urgent intervention and this is reflected in frequent hospital readmissions [1]. Similarity was found in the aspects addressed in each consultation with the patient in the selected studies, both in the HV and telephone contacts. Although the studies are not exclusively Brazilian, the approach for patients with HF in other countries was similar to the recommendations of the latest Brazilian HF guideline and other international guidelines, such as the European Society of Cardiology, American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association and Canadian Cardiovascular Society, which highlights clinical assessment and support in relation to adequate food, therapeutic adherence and behavioral adjustments to stimulate self-care [8]. This review showed benefits in reducing mortality and readmission when nurses held the following-up of patients after hospital discharge with face-to-face assessments combined with telephone call interventions. However, the ideal duration of post-discharge follow-up and the number of personal assessments and telephone consultations were not defined as our primary outcome. Therefore, a new meta-analysis that includes this objective is suggested.

The meta-analysis carried out by Gandhi et al. [25] showed a reduction in readmission and mortality in the group of patients who were followed up for ≥3 months in a HF clinic after recent decompensation that required a visit to the emergency room or hospitalization. Other studies recommend that the first home visit be carried out at least in the first 14 days after discharge [8] and within the period considered most critical for readmission (first 30 days after discharge) [26].

Before establishing the intervention strategy, health professionals should determine the stage of HF, the functional status verified in previous assessments, the date of the last hospitalization, the patient’s clinical comorbidities, as well as the availability of human and financial resources to perform the follow-up. Ten of the studies selected in this systematic review reported the necessary follow-up time [12,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22], except for Bento and Brofman [13]. This process should be adapted to the reality experienced by patients and their caregivers when moving from a technologically supported environment and with a multidisciplinary team (hospital) to another that does not have essential resources for the continuity of care in the most appropriate way (home).

Hospital readmissions related to HF are considered preventable, and the prevention of this problem remains a major focus of care in the management of patients with HF [27]. However, reduction of hospital readmissions and mortality, as a primary outcome, should not always be considered a positive outcome of an intervention, as the results that facilitate the reduction of hospital hospitalization can be translated into higher mortality rates of patients who decompensated the disease and were unable to access the health service [28,29]. Thus, hospitalization can often provide the opportunity to adjust care [30]. Comorbidities can impact the results and are important considerations before the allocation of patients, in order to avoid bias in the results of the study [11].

Some criteria were used in the studies of this review to reduce the impact on the outcome of the proposed intervention, such as exclusion of patients unable or unwilling to comply with the proposed intervention [13,14,17]; those with severe psychiatric disorders or cognitive impairment [16,17,19,21] and recent acute myocardial infarction or stroke [13,14,16,20]; those in the postoperative period from heart surgery or other scheduled surgery [12,13,14,16,22] or end-stage of HF [18]; those in an acute phase secondary to another comorbidity [20]; those with diseases resulting in reduced life expectancy [13,14,15,16,19]; and those on dialysis as a result of kidney disease [16,19].

The differences in the methodologies of each study did not negatively influence the analysis of this review. The heterogeneity of the articles included for hospital readmission outcome analysis was considered moderate (I2 = 39%), and the eight articles were considered homogeneous in terms of mortality analysis (I2 = 0%). In addition, a sensitivity analysis was carried out for the primary outcome of readmission, as the studies showed moderate heterogeneity with no substantial change observed in the grouped RR, indicating that no individual study had a considerable influence on the grouped estimate.

In addition to clinical deterioration, other aspects contribute to the probability of hospital readmission and mortality, such as psychosocial and socioeconomic factors [28,29,31]. Consequently, new methods for treating the disease, with consequent improvement in psychosocial aspects, are currently needed [32].

Some RCT show that the lack of follow-up focused on patients’ deficits for disease control, such as knowledge and self-care, results in a greater number of hospital readmissions in the CG [3,33]. A nursing intervention based on recommendations for self-care and the distribution of educational booklets was effective in improving quality of life (QoL) components over six months [34]. These data allow us to understand the importance of educational intervention aimed at controlling multiple factors that lead to hospital readmission, aiming to influence behavioral factors patient related to prevent readmissions, such as therapeutic non-adherence and nutritional imprudence [35].

In another aspect, this review showed that constant hospitalizations have an economic impact both for the patient in maintaining self-care and for the health systems that offer care during hospitalization [12,19]. In this sense, it means that in order to carry to some type of intervention aimed at reducing harmful clinical outcomes for the patient, such as hospital readmission and mortality, the reduction costs during a longer survival time should also be taken into account.

The specificities found around the world in relation to health systems require that caregivers can assist patients with heart failure, considering each scenario to achieve the objectives proposed for this care. In Brazil, which has a unified and free health system (SUS, as per its Portuguese acronym), home care is provided by health professionals who provide services in a defined area for the coverage of these professionals. As for the studies listed in this meta-analysis, the proposed follow-up with HV and telephone contact was carried out by professionals belonging to the hospitals linked to each study, with the assistance of their respective funding agency.

This review has some limitations, such as not establishing the ideal number of HV and telephone consultation, an ideal period of follow-up after hospital discharge and not stratification by groups that may benefit from the proposed intervention. However, the meta-analysis showed effectiveness in reducing the outcomes of readmission and mortality with HV and telephone contact made by nurses.

5. Conclusions

Evidence indicates that the use of HV and telephone contact for patient follow-up after hospital discharge for HF decompensation contribute to a reduction in hospital readmission and mortality and is a potential educational strategy for nursing practice. Despite the limitations related to the short follow-up time and small sample size, as well as the absence of pre-established protocols in some of the RCT, the results presented were not compromised. In this review, some studies demonstrated benefits in knowledge, self-care, and QoL outcomes. Further studies of meta-analyses should be performed in order to evidence the cost-effectiveness of the educational intervention proposed in these and other outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.R.d.G.M., R.d.C.A.V., A.F.d.M. and E.S.-S.; methodology, C.R.d.G.M., R.d.C.A.V., A.F.d.M., C.D.d.F. and E.S.-S.; validation, C.R.d.G.M., R.d.C.A.V., A.F.d.M., C.D.d.F., A.S.B. and E.S.-S.; formal analysis, C.R.d.G.M., R.d.C.A.V., A.F.d.M., Y.A.C.F., A.S.B. and E.S.-S.; investigation, C.R.d.G.M., A.S.O., A.C.M.T., Y.A.C.F. and E.S.-S.; writing—original draft preparation, C.R.d.G.M., R.d.C.A.V., A.F.d.M. and E.S.-S.; writing—review and editing, C.R.d.G.M., R.d.C.A.V. and E.S.-S.; visualization, C.R.d.G.M., R.d.C.A.V., A.F.d.M., A.S.B., C.D.d.F. and E.S.-S.; supervision, E.S.-S.; project administration, E.S.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Search strategy used in PubMed, SciELO, CINAHL, Cochrane, Google Scholar, Clinical Trials, and OpenThesis databases.

Table A1.

Search strategy used in PubMed, SciELO, CINAHL, Cochrane, Google Scholar, Clinical Trials, and OpenThesis databases.

| BASE | Search Strategy |

|---|---|

| PubMed | (((“Heart Failure”[Mesh] OR “Heart Failure” OR “Cardiac Failure” OR “Heart Decompensation” OR “Heart Failure, Right Sided” OR “Right-Sided Heart Failure” OR “Right Sided Heart Failure” OR “Myocardial Failure” OR “Congestive Heart Failure” OR “Heart Failure, Congestive” OR “Heart Failure, Left Sided” OR “Left Sided Heart Failure”)) AND ((“Patient Education as Topic”[Mesh] OR “Education, Patient” OR “Patient Education” OR “Education of Patients” OR “Self Care”[Mesh] OR “Self-Care” OR “Nursing Care”[Mesh] OR “Nursing Care” OR “Care, Nursing” OR “Management, Nursing Care” OR “Nursing Care Management” OR “educative intervention” OR “educational intervention” OR “nursing intervention”))) AND ((((clinical[Title/Abstract] AND trial[Title/Abstract]) OR clinical trials as topic[MeSH Terms] OR clinical trial[Publication Type] OR random*[Title/Abstract] OR random allocation[MeSH Terms] OR therapeutic use[MeSH Subheading]))) |

| SciELO | ((“Heart Failure” OR “Heart Failure, Systolic” OR “Heart Failure, Diastolic”) AND (“Nursing” OR “Nursing Assessment” OR “Nursing Care” OR “Cardiovascular Nursing” OR “Home Health Nursing” OR “Patient Care Planning”) AND (“Patient Education as topic” OR “Patient Education Handout”)) ((“Insuficiência cardíaca” OR “Insuficiência Cardíaca sistólica” OR “Insuficiência Cardíaca diastólica”)) AND ((enfermagem OR “Avaliação em Enfermagem” OR “Cuidados de Enfermagem” OR “Enfermagem Cardiovascular” OR “Enfermagem Domiciliar” OR “Planejamento de Assistência ao Paciente”)) AND ((“Educação de Pacientes como Assunto” OR “Prospecto para Educação de Pacientes”)) ((“Insuficiencia Cardíaca” OR “Insuficiencia Cardíaca Sistólica” OR “Insuficiencia Cardíaca Diastólica” AND (Enfermería OR “Evaluación en Enfermería” OR “Atención de Enfermería” OR “Enfermería Cardiovascular” OR “Cuidados de Enfermería en el Hogar” OR “Planificación de Atención al Paciente”) AND (“Educación del Paciente como Asunto” OR “Folleto Informativo para Pacientes”)) |

| CINAHL | ((MM “Heart Failure”) OR (MM “Heart Injuries”) OR (MM “Heart Hypertrophy”) OR (MM “Heart”) OR (MM “Heart Diseases”) OR (MH “Coronary Disease”) OR (MM “Cardiac Patients”) AND (MM “Education, Nursing, Associate”) OR (MM “Practical Nursing”) OR (MM “Nursing Protocols”) OR (MM “Nursing Interventions”) OR (MM “Nursing Care Plans”) OR (MM “Education, Nursing, Practical”) OR (MH “Nursing Practice”) AND (MM “Patient Education”) OR (MM “Patient Discharge Education”) OR (MM “Cardiac Patients”) OR (MM “Patient Orientation”)) |

| COCHRANE | (“Heart Failure” OR “Heart Failure” OR “Cardiac Failure” OR “Heart Decompensation” OR “Heart Failure, Right Sided” OR “Right-Sided Heart Failure” OR “Right Sided Heart Failure” OR “Myocardial Failure” OR “Congestive Heart Failure” OR “Heart Failure, Congestive” OR “Heart Failure, Left Sided” OR “Left Sided Heart Failure”) AND (“Patient Education as Topic” OR “Education, Patient” OR “Patient Education” OR “Education of Patients” OR “Self Care” OR “Self-Care”) AND (“Nursing Care” OR “Nursing Care” OR “Care, Nursing” OR “Management, Nursing Care” OR “Nursing Care Management” OR “educative intervention” OR “educational intervention” OR “nursing intervention”) |

| Google Scholar | (“Heart Failure”) and (“Nursing” or “Patient Education”) |

| Open Thesis | ((“Heart Failure”) AND (“Nurse” OR “Nursing” OR “Nurses”) AND (“Patient education” OR “Self-care”)) |

| Clinicaltrials.gov | “Nursing” and “Heart Failure” and “Patient Education” |

Table A2.

Risk of bias assessment.

Table A2.

Risk of bias assessment.

| Authors | Random Sequence Generation | Allocation Concealment | Blinding of Participants and Professionals | Blinding of Outcome Evaluators | Incomplete Outcomes | Selective Outcome Report | Other Sources of Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adlbrecht et al., 2011 [12] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Bento; Brofman, 2008 [13] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Blue et al., 2001 [14] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Kwok et al., 2006 [15] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Leventhal et al., 2011 [16] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Mizukawa et al., 2019 [17] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Quinn, 2006 [18] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Riegel et al., 2002 [19] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Souza et al., 2014 [20] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Wong et al., 2016 [21] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Yu et al., 2015 [22] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

(+) low risk of bias, (-) high risk of bias, (?) Risk of uncertain bias.

References

- BocchiI, E.A.; BragaI, F.G.M.; FerreiraI, S.M.A.; Rohde, L.E.P.; de Oliveira, W.A.; de Almeida, D.R.; Moreir, M.d.C.V.; Bestetti, R.B.; Bordignon, S.; Azevedo, C.; et al. Diretriz Brasileira de Insuficiência Cardíaca Crônica. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2009, 93, 3–70. [Google Scholar]

- Yancy, C.W.; Jessup, M.; Bozkurt, B.; Butler, J.; Casey, D.E., Jr.; Colvin, M.M.; Drazner, M.H.; Filippatos, G.S.; Fonarow, G.C.; Givertz, M.M.; et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA Focused Update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. Circulation 2017, 136, e137–e161. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Oscalices, M.I.L.; Okuno, M.F.P.; Lopes, M.C.B.T.; Campanharo, C.R.V.; Batista, R.E.A. Discharge guidance and telephone follow-up in the therapeutic adherence of heart failure: Randomized clinical trial. Rev. Lat. Am. Enferm. 2019, 27, e3159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambrosy, A.P.; Fonarow, G.C.; Butler, J.; Chioncel, O.; Greene, S.J.; Vaduganathan, M.; Nodari, S.; Lam, C.S.; Sato, N.; Shah, A.N.; et al. The Global Health and Economic Burden of Hospitalizations for Heart Failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014, 63, 1123–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, Y. Multidisciplinary management of heart failure just beginning in Japan. J. Cardiol. 2015, 66, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros e Silva, P.G.M.; Ribeiro, D.J.; Fernandes, V.A.; Rinaldi, D.; Ramos, D.; Okada, M. Initial Impact of a Disease Management Program on Heart Failure in a Private Cardiology Hospital. Rev. Bras. Cardiol. 2014, 27, 90–96. [Google Scholar]

- Ezekowitz, J.A.; O’Meara, E.; McDonald, M.A.; Abrams, H.; Chan, M.; Ducharme, A.; Giannetti, N.; Grzeslo, A.; Hamilton, P.G.; Heckman, G.A.; et al. Comprehensive update of the Canadian cardiovascular society guidelines for the management of heart failure. Can. J. Cardiol. 2017, 33, 1342–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohde, L.E.P.; Montera, M.W.; Bocchi, E.A.; Clausell, N.O.; Albuquerque, D.C.d.; Rassi, S.; Colafranceschi, A.S.; Freitas, A.F.d., Jr.; Ferraz, A.S.; Biolo, A.; et al. Coordinating committee on heart failure guideline. Brazilian guideline of chronic and acute heart failure. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2018, 111, 436–539. [Google Scholar]

- Azeka, E.; Jatene, M.B.; Jatene, I.B.; Horowitz, E.S.K.; Branco, K.C.; Neto, J.D.S.; Miura, N.; Mattos, S.; Afiune, J.Y.; Tanaka, A.C.; et al. Brazilian guideline of heart failure and heart transplantation, in fetus, children and adults with congenital heart disease, of the Brazilian Society of Cardiology. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2014, 103, 1–126. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Landis, J.R.; Koch, G.G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977, 33, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A. (Eds.) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.1 (Updated September 2020); John Wiley & Sons: Cochrane, AB, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Adlbrecht, C.; Huelsmann, M.; Berger, R.; Moertl, D.; Strunk, G.; Oesterle, A.; Ahmadi, R.; Szucs, T.; Pacher, R. Cost analysis and cost-effectiveness of NT-proBNP-guided heart failure specialist care in addition to home-based nurse care. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2011, 41, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bento, V.F.R.; Brofman, P.R.S. Impact of the nursing consultation on the frequency of hospitalizations in patients with heart failure in Curitiba, Parana State. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2009, 92, 490–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blue, L.; Lang, E.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Davie, A.P.; McDonagh, T.A.; Murdoch, D.R.; Petrie, M.C.; Connolly, E.; Norrie, J.; Round, C.E.; et al. Randomised controlled trial of specialist nurse intervention in heart failure. BMJ 2001, 323, 715–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwok, T.; Lee, J.; Woo, J.; Lee, D.T.; Griffith, S. A randomized controlled trial of a community nurse-supported hospital discharge programme in older patients with chronic heart failure. J. Clin. Nurs. 2008, 1, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leventhal, M.E.; Denhaerynck, K.; Rocca, H.-P.B.-L.; Burnand, B.; Conca-Zeller, A.; Bernasconi, A.T.; Mahrer-Imhof, R.; Froelicher, E.S.; De Geest, S. Swiss Interdisciplinary Management Programme for Heart Failure (SWIM-HF): A randomised controlled trial study of an outpatient inter-professional management programme for heart failure patients in Switzerland. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2011, 141, w13171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizukawa, M.; Moriyama, M.; Yamamoto, H.; Rahman, M.; Naka, M.; Kitagawa, T.; Kobayashi, S.; Oda, N.; Yasunobu, Y.; Tomiyama, M.; et al. Nurse-Led Collaborative Management Using Telemonitoring Improves Quality of Life and Prevention of Rehospitalization in Patients with Heart Failure. Int. Heart J. 2019, 60, 1293–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinn, C. Low-technology heart failure care in home health: Improving patient outcomes. Home Healthc. Now 2006, 8, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riegel, B.; Carlson, B.; Kopp, Z.; LePetri, B.; Glaser, D.; Unger, A. Effect of a standardized nurse case-management telephone intervention on resource use in patients with chronic heart failure. Arch. Intern. Med. 2002, 6, 705–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Souza, E.N.; Rohde, L.E.; Ruschel, K.B.; Mussi, C.M.; Beck-da-Silva, L.; Biolo, A.; Clausell, N.; Rabelo-Silva, E.R. A nurse-based strategy reduces heart failure morbidity in patients admitted for acute decompensated heart failure in Brazil: The HELEN-II clinical trial. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2014, 9, 1002–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, F.K.Y.; Ng, A.Y.M.; Lee, P.H.; Lam, P.-T.; Ng, J.S.C.; Ng, N.H.Y.; Sham, M.M.K. Effects of a transitional palliative care model on patients with end-stage heart failure: A randomised controlled trial. Heart 2016, 102, 1100–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, D.S.F.; Lee, D.T.F.; Stewart, S.; Thompson, D.R.; Choi, K.; Yu, C. Effect of Nurse-Implemented Transitional Care for Chinese Individuals with Chronic Heart Failure in Hong Kong: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2015, 63, 1583–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Spall, H.G.C.; Rahman, T.; Mytton, O.; Ramasundarahettige, C.; Ibrahim, Q.; Kabali, C.; Coppens, M.; Haynes, R.B.; Connolly, S. Comparative effectiveness of transitional care services in patients discharged from the hospital with heart failure: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2017, 19, 1427–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slyer, J.T.; Concert, C.M.; Eusebio, A.M.; Rogers, M.E.; Singleton, J. A systematic review of the effectiveness of nurse coordinated transitioning of care on readmission rates for patients with heart failure. JBI Evid. Synth. 2011, 9, 464–490. [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi, S.; Mosleh, W.; Sharma, U.C.; Demers, C.; Farkouh, M.E.; Schwalm, J.-D. Multidisciplinary heart failure clinics are associated with lower heart failure hospitalization and mortality: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Can. J. Cardiol. 2017, 33, 1237–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aliti, G.B.; Rabelo, E.R.; Domingues, F.B.; Clausell, N. Educational settings in the management of patients with heart failure. Rev. Lat. Am. Enferm. 2007, 15, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Strömberg, A. The crucial role of patient education in heart failure. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2005, 3, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joynt, K.E.; Jha, A.K. Thirty-day readmissions—Truth and consequences. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 15, 1366–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Au, A.G.; McAlister, F.A.; Bakal, J.A.; Ezekowitz, J.; Kaul, P.; van Walraven, C. Predicting the risk of unplanned readmission or death within 30 days of discharge after a heart failure hospitalization. Am. Heart J. 2012, 164, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidenreich, P.A.; Sahay, A.; Kapoor, J.R.; Pham, M.X.; Massie, B. Divergent trends in survival and readmission following a hospitalization for heart failure in the Veterans Affairs health care system 2002 to 2006. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2010, 56, 362–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desai, A.S.; Stevenson, L.W. Rehospitalization for heart failure: Predict or prevent? Circulation 2012, 126, 501–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Amaral, D.R.; Rossi, M.B.; Lopes, C.T.; de Lima Lopes, J. Nonpharmacological interventions to improve quality of life in heart failure: An integrative review. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2017, 70, 198–209. [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro, R.J.; Viacava, F.; Travassos, C.; Brito, A.S. Gender, morbidity, access and utilization of health services in Brazil. Ciência Saúde Coletiva 2002, 7, 105–109. [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar, S.B.; Reilly, C.M.; Gary, R.; Higgins, M.K.; Culler, S.; Butts, B.; Butler, J. Randomized clinical trial of an integrated self-care intervention for persons with heart failure and diabetes: Quality of life and physical functioning outcomes. J. Card. Fail. 2015, 21, 719–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gheorghiade, M.; Vaduganathan, M.; Fonarow, G.C.; Bonow, R.O. Rehospitalization for heart failure: Problems and perspectives. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013, 61, 391–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).