Coronary Bifurcation PCI—Part II: Advanced Considerations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. SB Considerations

2.1. Factors Predicting SB Compromise

2.2. Plaque Shift and Carina Shift

2.3. Situations That Call for a Two-Stent Approach Upfront

2.4. Role of Physiologic Testing for SB Protection

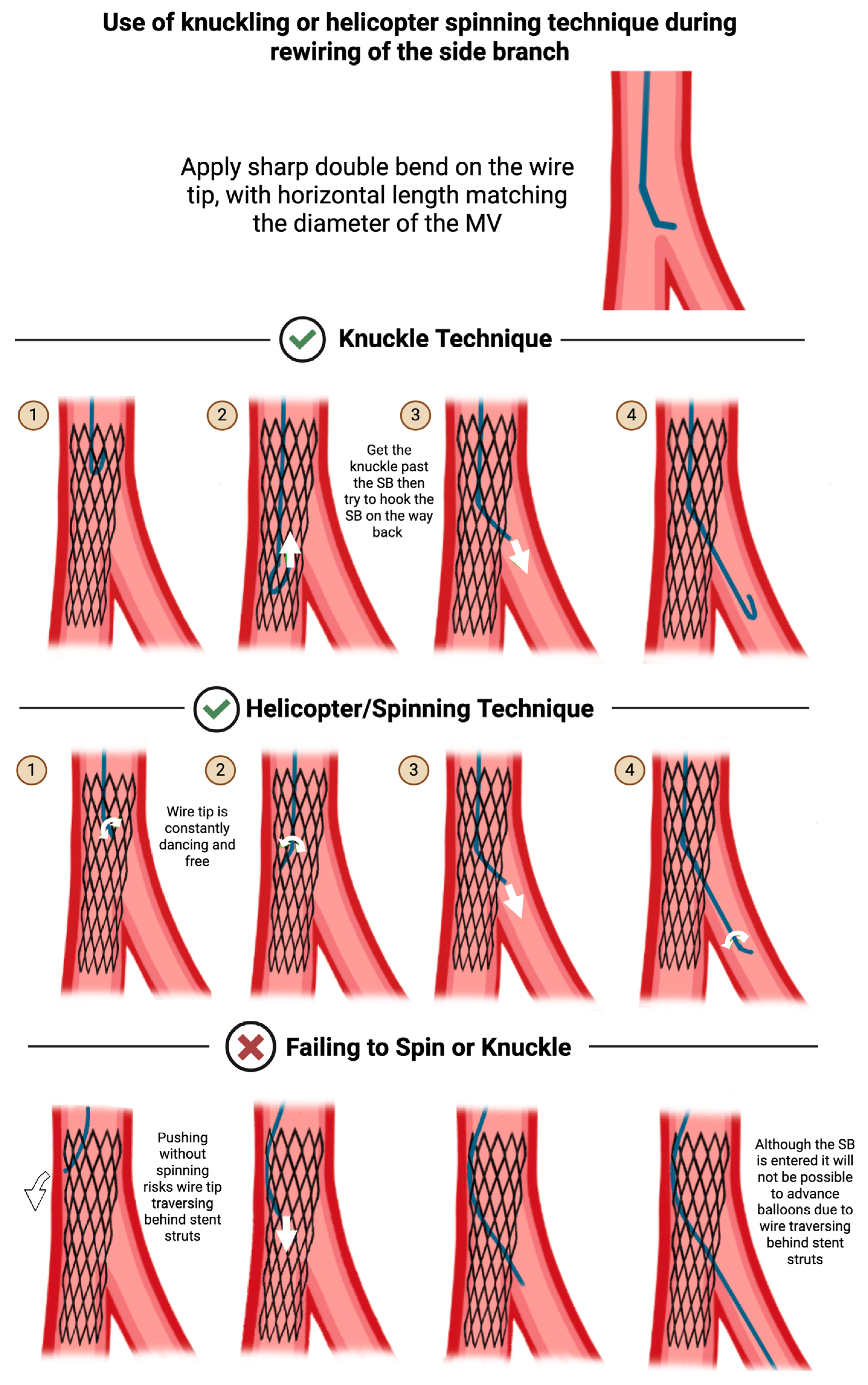

3. SB Protection, Wiring, and Rewiring

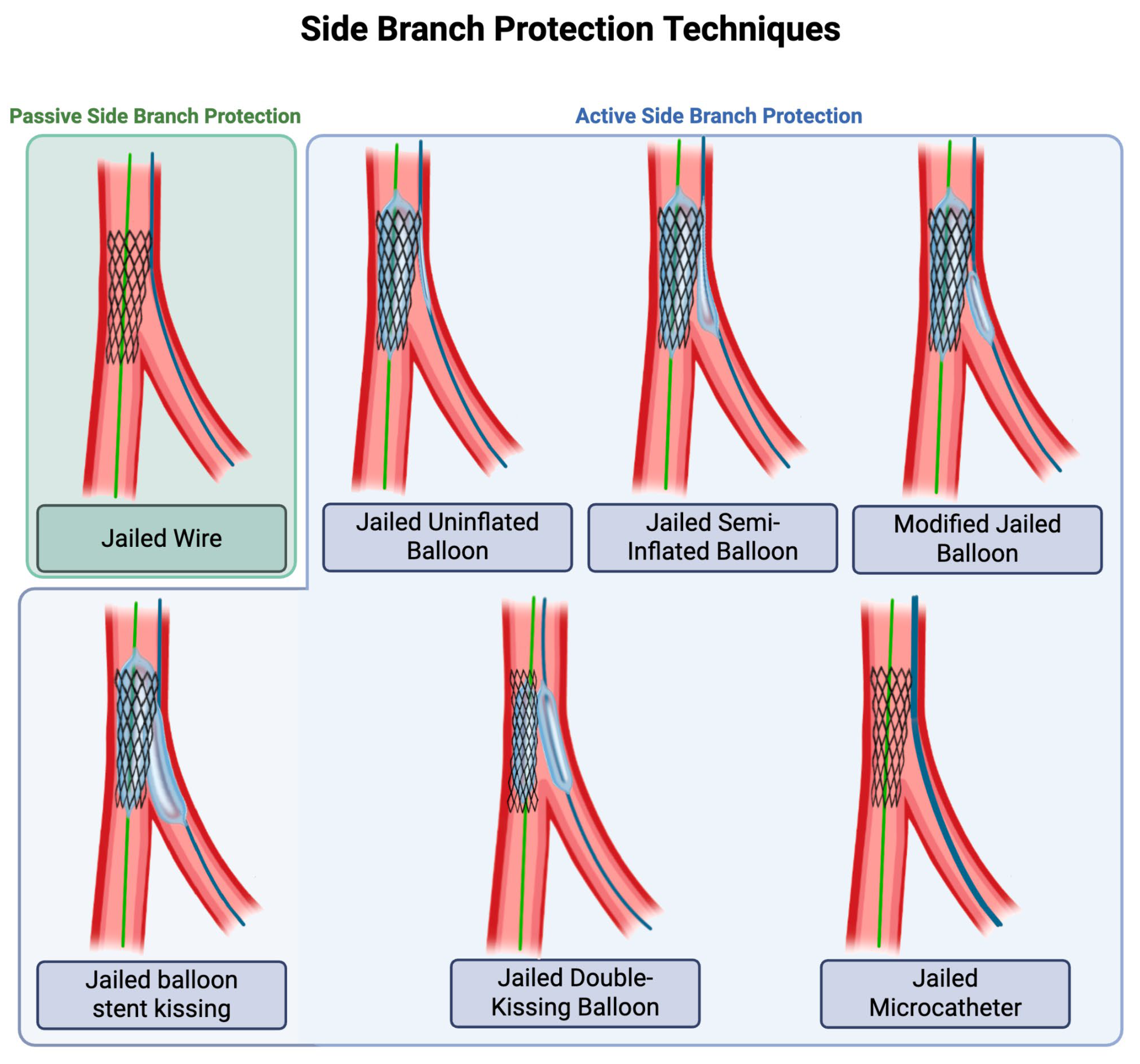

3.1. Techniques for Passive and Active SB Protection

3.2. Three-Wire vs. Two-Wire Technique for Rewiring the SB

3.3. Tips for Maintaining or Regaining SB Access

3.4. Guidewire Entrapment in the SB

4. Algorithm for Bifurcation PCI

5. Outcomes of Randomized Trials

5.1. Synopsis of Landmark Trials of Provisional vs. Two-Stent Strategies

5.2. Synopsis of Landmark Trials Focusing on Complex Bifurcations

5.3. Synopsis of Landmark Trials Focusing on Left Main Bifurcations

6. Evolving Techniques

6.1. Role of Intravascular Imaging in Bifurcation PCI

6.2. Role of Drug-Coated Balloons in SB Treatment

6.3. Role of Bifurcation-Dedicated Stents

6.4. Role of Bioresorbable Vascular Scaffolds and Bioadaptor Stents

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Albiero, R.; Burzotta, F.; Lassen, J.F.; Lefèvre, T.; Banning, A.P.; Chatzizisis, Y.S.; Johnson, T.W.; Ferenc, M.; Pan, M.; Daremont, O.; et al. Treatment of coronary bifurcation lesions, part I: Implanting the first stent in the provisional pathway. The 16th expert consensus document of the European Bifurcation Club. EuroIntervention 2022, 18, e362–e376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollanen, S.; Damrongwatanasuk, R.; Bae, J.Y.; Wen, J.; Nanna, M.G.; Damluji, A.A.; Mamas, M.A.; Hanna, E.B.; Hu, J.R. Coronary Bifurcation PCI—Part I: Fundamentals. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2025, 12, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Peng, H.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, J. Predictors and complications of side branch occlusion after recanalization of chronic total occlusions complicated with bifurcation lesions. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 4460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Xu, B.; Yin, D.; Li, Y.P.; He, Y.; You, S.J.; Qiao, S.B.; Wu, Y.J.; Yan, H.B.; Yang, Y.J.; et al. Clinical and angiographic predictors of major side branch occlusion after main vessel stenting in coronary bifurcation lesions. Chin. Med. J. 2015, 128, 1471–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iles, T.L.; Stankovic, G.; Lassen, J.F. “The significant other”: Evaluation of side branch ostial compromise in bifurcation stenting. Cardiol. J. 2020, 27, 474–477. [Google Scholar]

- Dou, K.; Zhang, D.; Xu, B.; Yang, Y.; Yin, D.; Qiao, S.; Wu, Y.; You, S.; Wang, Y.; Yan, R.; et al. An angiographic tool based on Visual estimation for Risk prEdiction of Side branch OccLusion in coronary bifurcation interVEntion: The V-RESOLVE score system. EuroIntervention 2016, 11, e1604–e1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, K.; Zhang, D.; Xu, B.; Yang, Y.; Yin, D.; Qiao, S.; Wu, Y.; Yan, H.; You, S.; Wang, Y.; et al. An angiographic tool for risk prediction of side branch occlusion in coronary bifurcation intervention: The RESOLVE score system (risk prediction of side branch occlusion in coronary bifurcation intervention). JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2015, 8 Pt A, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karanasos, A.; Tu, S.; van der Heide, E.; Reiber, J.H.; Regar, E. Carina shift as a mechanism for side-branch compromise following main vessel intervention: Insights from three-dimensional optical coherence tomography. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 2012, 2, 173–177. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Guan, C.; Chen, J.; Dou, K.; Tang, Y.; Yang, W.; Shi, Y.; Hu, F.; Song, L.; Yuan, J.; et al. Validation of bifurcation DEFINITION criteria and comparison of stenting strategies in true left main bifurcation lesions. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 10461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.L.; Sheiban, I.; Xu, B.; Jepson, N.; Paiboon, C.; Zhang, J.J.; Ye, F.; Sansoto, T.; Kwan, T.W.; Lee, M.; et al. Impact of the complexity of bifurcation lesions treated with drug-eluting stents: The DEFINITION study (Definitions and impact of complex bifurcation lesions on clinical outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention using drug-eluting stents). JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2014, 7, 1266–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, J.; Zhang, J.J.; Sheiban, I.; Santoso, T.; Munawar, M.; Tresukosol, D.; Xu, K.; Stone, G.W.; Chen, S.L.; DEFINITION II Investigators. 3-Year Outcomes After 2-Stent with Provisional Stenting for Complex Bifurcation Lesions Defined by DEFINITION Criteria. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2022, 15, 1310–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.L. DEFINITION criteria for left main bifurcation stenting—From clinical need to a formula. AsiaIntervention 2023, 9, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.J.; Ye, F.; Xu, K.; Kan, J.; Tao, L.; Santoso, T.; Munawar, M.; Tresukosol, D.; Li, L.; Sheiban, I.; et al. Multicentre, randomized comparison of two-stent and provisional stenting techniques in patients with complex coronary bifurcation lesions: The DEFINITION II trial. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 2523–2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.L.; Zhang, J.J.; Han, Y.; Kan, J.; Chen, L.; Qiu, C.; Jiang, T.; Tao, L.; Zeng, H.; Li, L.; et al. Double Kissing Crush Versus Provisional Stenting for Left Main Distal Bifurcation Lesions: DKCRUSH-V Randomized Trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017, 70, 2605–2617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, J.E.; Sen, S.; Dehbi, H.M.; Al-Lamee, R.; Petraco, R.; Nijjer, S.S.; Bhindi, R.; Lehman, S.J.; Walters, D.; Sapontis, J.; et al. Use of the Instantaneous Wave-free Ratio or Fractional Flow Reserve in PCI. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 1824–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Götberg, M.; Christiansen, E.H.; Gudmundsdottir, I.J.; Sandhall, L.; Danielewicz, M.; Jakobsen, L.; Olsson, S.E.; Öhagen, P.; Olsson, H.; Omerovic, E.; et al. Instantaneous Wave-free Ratio versus Fractional Flow Reserve to Guide PCI. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 1813–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.S.; Kim, U.; Yang, S.; Murasato, Y.; Louvard, Y.; Song, Y.B.; Kubo, T.; Johnson, T.W.; Hong, S.J.; Omori, H.; et al. Physiological Approach for Coronary Artery Bifurcation Disease: Position Statement by Korean, Japanese, and European Bifurcation Clubs. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2022, 15, 1297–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, B.K.; Kang, H.J.; Youn, T.J.; Chae, I.H.; Choi, D.J.; Kim, H.S.; Sohn, D.W.; Oh, B.H.; Lee, M.M.; Park, Y.B.; et al. Physiologic assessment of jailed side branch lesions using fractional flow reserve. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2005, 46, 633–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, B.K.; Rahman, M.N.; Tai, J.M.; Faheem, O. Jailed balloons for side branch protection: A review of techniques and literature: Jailed balloons for side branch protection. AsiaIntervention 2020, 6, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burzotta, F.; Trani, C.; Sianos, G. Jailed balloon protection: A new technique to avoid acute side-branch occlusion during provisional stenting of bifurcated lesions. Bench test report and first clinical experience. EuroIntervention 2010, 5, 809–813. [Google Scholar]

- Çaylı, M.; Şeker, T.; Gür, M.; Elbasan, Z.; Şahin, D.Y.; Elbey, M.A.; Çil, H. A Novel-Modified Provisional Bifurcation Stenting Technique: Jailed Semi-Inflated Balloon Technique. J. Interv. Cardiol. 2015, 28, 420–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shishido, K.; Moriyama, N.; Hayashi, T.; Yokota, S.; Miyashita, H.; Mashimo, Y.; Yokoyama, H.; Nishimoto, T.; Ochiai, T.; Tobita, K.; et al. The efficacy of modified jailed balloon technique for true bifurcation lesions. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2020, 96, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, S.; Shishido, K.; Moriyama, N.; Ochiai, T.; Mizuno, S.; Yamanaka, F.; Sugitatsu, K.; Tobita, K.; Matsumi, J.; Tanaka, Y.; et al. Modified jailed balloon technique for bifurcation lesions. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2018, 92, E218–E226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, W.B.; Zhang, W.; Liu, J.Y.; Zhang, F.; Mu, S.N.; Zhang, S.M.; Tang, H.; Liu, X.Q.; Li, X.Q.; Liu, B.C.; et al. Modified balloon-stent kissing technique avoid side-branch compromise for simple true bifurcation lesions. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2019, 19, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Z.; Li, L.; Wang, M.; Zhang, S.; Chen, Z.; Shen, Z. Innovative provisional stenting approach to treat coronary bifurcation lesions: Balloon-stent kissing technique. J. Invasive Cardiol. 2013, 25, 600–604. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Song, Y.; Cao, J.; Weng, X.; Zhang, F.; Dai, Y.; Lu, H.; Li, C.; Huang, Z.; Qian, J.; et al. Double kissing inflation outside the stent secures the patency of small side branch without rewiring. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2021, 21, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuno, T.; Sugiyama, T.; Imaeda, S.; Hashimoto, K.; Ryuzaki, T.; Yokokura, S.; Saito, T.; Yamazaki, H.; Tabei, R.; Kodaira, M.; et al. Novel Insights of Jailed Balloon and Jailed Corsair Technique for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention of Bifurcation Lesions. Cardiovasc. Revasc. Med. 2019, 20, 1065–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, K.; Zhang, D.; Pan, H.; Guo, N.; Li, L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, B.; Shen, Z.; Zhang, B.; et al. Active SB-P Versus Conventional Approach to the Protection of High-Risk Side Branches: The CIT-RESOLVE Trial. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2020, 13, 1112–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhao, Z.; Gao, G.; Xu, H.; Wang, H.; Liu, S.; Yin, D.; Feng, L.; Zhu, C.; Wang, Y.; et al. Jailed Balloon Technique Is Superior to Jailed Wire Technique in Reducing the Rate of Side Branch Occlusion: Subgroup Analysis of the Conventional Versus Intentional StraTegy in Patients with High Risk PrEdiction of Side Branch OccLusion in Coronary Bifurcation InterVEntion Trial. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 814873. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, Q.; Zheng, B.; Liu, J.; Zhang, B.; Chen, M.; Li, J.; Huo, Y. Active Versus Conventional Side Branch Protection Strategy for Coronary Bifurcation Lesions. Int. Heart J. 2021, 62, 1241–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steigen, T.K.; Maeng, M.; Wiseth, R.; Erglis, A.; Kumsars, I.; Narbute, I.; Gunnes, P.; Mannsverk, J.; Meyerdierks, O.; Rotevatn, S.; et al. Randomized study on simple versus complex stenting of coronary artery bifurcation lesions: The Nordic bifurcation study. Circulation 2006, 114, 1955–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferenc, M.; Gick, M.; Kienzle, R.P.; Bestehorn, H.P.; Werner, K.D.; Comberg, T.; Kuebler, P.; Büttner, H.J.; Neumann, F.J. Randomized trial on routine vs. provisional T-stenting in the treatment of de novo coronary bifurcation lesions. Eur. Heart J. 2008, 29, 2859–2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colombo, A.; Bramucci, E.; Saccà, S.; Violini, R.; Lettieri, C.; Zanini, R.; Sheiban, I.; Paloscia, L.; Grube, E.; Schofer, J.; et al. Randomized study of the crush technique versus provisional side-branch stenting in true coronary bifurcations: The CACTUS (Coronary Bifurcations: Application of the Crushing Technique Using Sirolimus-Eluting Stents) Study. Circulation 2009, 11, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hildick-Smith, D.; de Belder, A.J.; Cooter, N.; Curzen, N.P.; Clayton, T.C.; Oldroyd, K.G.; Bennett, L.; Holmberg, S.; Cotton, J.M.; Glennon, P.E.; et al. Randomized trial of simple versus complex drug-eluting stenting for bifurcation lesions: The British Bifurcation Coronary Study: Old, new, and evolving strategies. Circulation 2010, 121, 1235–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.H.; Lee, J.H.; Roh, J.H.; Ahn, J.M.; Yoon, S.H.; Park, D.W.; Lee, J.Y.; Yun, S.C.; Kang, S.J.; Lee, S.W.; et al. Randomized Comparisons Between Different Stenting Approaches for Bifurcation Coronary Lesions with or Without Side Branch Stenosis. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2015, 8, 550–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hildick-Smith, D.; Behan, M.W.; Lassen, J.F.; Chieffo, A.; Lefèvre, T.; Stankovic, G.; Burzotta, F.; Pan, M.; Ferenc, M.; Bennett, L.; et al. The EBC TWO Study (European Bifurcation Coronary TWO): A Randomized Comparison of Provisional T-Stenting Versus a Systematic 2 Stent Culotte Strategy in Large Caliber True Bifurcations. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2016, 9, e003643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumsars, I.; Holm, N.R.; Niemelä, M.; Erglis, A.; Kervinen, K.; Christiansen, E.H.; Maeng, M.; Dombrovskis, A.; Abraitis, V.; Kibarskis, A.; et al. Randomised comparison of provisional side branch stenting versus a two-stent strategy for treatment of true coronary bifurcation lesions involving a large side branch: The Nordic-Baltic Bifurcation Study IV. Open Heart 2020, 7, e000947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behan, M.W.; Holm, N.R.; de Belder, A.J.; Cockburn, J.; Erglis, A.; Curzen, N.P.; Niemelä, M.; Oldroyd, K.G.; Kervinen, K.; Kumsars, I.; et al. Coronary bifurcation lesions treated with simple or complex stenting: 5-year survival from patient-level pooled analysis of the Nordic Bifurcation Study and the British Bifurcation Coronary Study. Eur. Heart J. 2016, 37, 1923–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katritsis, D.G.; Siontis, G.C.M.; Ioannidis, J.P.A. Double versus single stenting for coronary bifurcation lesions: A meta-analysis. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2009, 2, 409–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.L.; Zhang, J.J.; Ye, F.; Chen, Y.D.; Patel, T.; Kawajiri, K.; Lee, M.; Kwan, T.W.; Mintz, G.; Tan, H.C. Study comparing the double kissing (DK) crush with classical crush for the treatment of coronary bifurcation lesions: The DKCRUSH-1 Bifurcation Study with drug-eluting stents. Eur. J. Clin. Invest 2008, 38, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.L.; Santoso, T.; Zhang, J.J.; Ye, F.; Xu, Y.W.; Fu, Q.; Kan, J.; Paiboon, C.; Zhou, Y.; Ding, S.Q.; et al. A randomized clinical study comparing double kissing crush with provisional stenting for treatment of coronary bifurcation lesions: Results from the DKCRUSH-II (Double Kissing Crush versus Provisional Stenting Technique for Treatment of Coronary Bifurcation Lesions) trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2011, 57, 914–920. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.L.; Santoso, T.; Zhang, J.J.; Ye, F.; Xu, Y.W.; Fu, Q.; Kan, J.; Zhang, F.F.; Zhou, Y.; Xie, D.J.; et al. Clinical Outcome of Double Kissing Crush Versus Provisional Stenting of Coronary Artery Bifurcation Lesions: The 5-Year Follow-Up Results from a Randomized and Multicenter DKCRUSH-II Study (Randomized Study on Double Kissing Crush Technique Versus Provisional Stenting Technique for Coronary Artery Bifurcation Lesions). Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2017, 10, e004497. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.L.; Xu, B.; Han, Y.L.; Sheiban, I.; Zhang, J.J.; Ye, F.; Kwan, T.W.; Paiboon, C.; Zhou, Y.J.; Lv, S.Z.; et al. Clinical Outcome After DK Crush Versus Culotte Stenting of Distal Left Main Bifurcation Lesions: The 3-Year Follow-Up Results of the DKCRUSH-III Study. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2015, 8, 1335–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hildick-Smith, D.; Egred, M.; Banning, A.; Brunel, P.; Ferenc, M.; Hovasse, T.; Wlodarczak, A.; Pan, M.; Schmitz, T.; Silvestri, M.; et al. The European bifurcation club Left Main Coronary Stent study: A randomized comparison of stepwise provisional vs. systematic dual stenting strategies (EBC MAIN). Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 3829–3839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arunothayaraj, S.; Egred, M.; Banning, A.P.; Brunel, P.; Ferenc, M.; Hovasse, T.; Wlodarczak, A.; Pan, M.; Schmitz, T.; Silvestri, M.; et al. Stepwise Provisional Versus Systematic Dual-Stent Strategies for Treatment of True Left Main Coronary Bifurcation Lesions. Circulation 2025, 151, 612–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Gao, X.; Kan, J.; Ge, Z.; Han, L.; Lu, S.; Tian, N.; Lin, S.; Lu, Q.; Wu, X.; et al. Intravascular Ultrasound Versus Angiography-Guided Drug-Eluting Stent Implantation: The ULTIMATE Trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 72, 3126–3137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zito, A.; Burzotta, F.; Aurigemma, C.; Romagnoli, E.; Paraggio, L.; Fracassi, F.; Lunardi, M.; Cappannoli, L.; Bianchini, F.; Trani, C.; et al. Intravascular imaging for percutaneous coronary intervention on bifurcation and unprotected left main lesions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Heart 2025, 12, e003026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, N.R.; Andreasen, L.N.; Neghabat, O.; Laanmets, P.; Kumsars, I.; Bennett, J.; Olsen, N.T.; Odenstedt, J.; Hoffmann, P.; Dens, J.; et al. OCT or Angiography Guidance for PCI in Complex Bifurcation Lesions. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 1477–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassen, J.F.; Albiero, R.; Johnson, T.W.; Burzotta, F.; Lefèvre, T.; Iles, T.L.; Pan, M.; Banning, A.P.; Chatzizisis, Y.S.; Ferenc, M.; et al. Treatment of coronary bifurcation lesions, part II: Implanting two stents. The 16th expert consensus document of the European Bifurcation Club. EuroIntervention 2022, 18, 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burzotta, F.; Louvard, Y.; Lassen, J.F.; Lefèvre, T.; Finet, G.; Collet, C.; Legutko, J.; Lesiak, M.; Hikichi, Y.; Albiero, R.; et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention for bifurcation coronary lesions using optimised angiographic guidance: The 18th consensus document from the European Bifurcation Club. EuroIntervention 2024, 20, e915–e926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.F.; Ge, Z.; Kong, X.Q.; Kan, J.; Han, L.; Lu, S.; Tian, N.L.; Lin, S.; Lu, Q.H.; Wang, X.Y.; et al. 3-Year Outcomes of the ULTIMATE Trial Comparing Intravascular Ultrasound Versus Angiography-Guided Drug-Eluting Stent Implantation. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2021, 14, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladwiniec, A.; Walsh, S.J.; Holm, N.R.; Hanratty, C.G.; Mäkikallio, T.; Kellerth, T.; Hildick-Smith, D.; Mogensen, L.J.H.; Hartikainen, J.; Menown, I.B.A.; et al. Intravascular ultrasound to guide left main stem intervention: A NOBLE trial substudy. EuroIntervention 2020, 16, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Kang, D.Y.; Ahn, J.M.; Kweon, J.; Choi, Y.; Kim, H.; Lee, J.; Chae, J.; Kang, S.J.; Park, D.W.; et al. Optimal Minimal Stent Area and Impact of Stent Underexpansion in Left Main Up-Front 2-Stent Strategy. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2024, 17, e013006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, Z.; Kan, J.; Gao, X.F.; Kong, X.Q.; Zuo, G.F.; Ye, F.; Tian, N.L.; Lin, S.; Liu, Z.Z.; Sun, Z.; et al. Comparison of intravascular ultrasound-guided with angiography-guided double kissing crush stenting for patients with complex coronary bifurcation lesions: Rationale and design of a prospective, randomized, and multicenter DKCRUSH VIII trial. Am. Heart J. 2021, 234, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kereiakes, D.J. “Leave Nothing Behind”: Strategy of Choice for Small Coronaries? JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2020, 13, 2850–2852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, Q.M.; Zhao, X.; Han, Y.L.; Gao, L.L.; Zheng, Y.; Li, Z.Q.; Yang, P.; Cong, H.L.; Gao, C.Y.; Jiang, T.M.; et al. A drug-eluting Balloon for the trEatment of coronarY bifurcatiON lesions in the side branch: A prospective multicenter ranDomized (BEYOND) clinical trial in China. Chin. Med. J. 2020, 133, 899–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Tian, N.; Kan, J.; Li, P.; Wang, M.; Sheiban, I.; Figini, F.; Deng, J.; Chen, X.; Santoso, T.; et al. Drug-Coated Balloon Angioplasty of the Side Branch During Provisional Stenting: The Multicenter Randomized DCB-BIF Trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2025, 85, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, A.A.; Jayaraman, B. Dedicated bifurcation stents. Indian Heart J. 2012, 64, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundeken, M.J.; Magro, M.; Gil, R.; Briguori, C.; Sardella, G.; Berland, J.; Wykrzykowska, J.J.; Serruys, P.W. Dedicated stents for distal left main stenting. EuroIntervention 2015, 11 (Suppl. S5), V129–V134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Stankovic, G.; Lassen, J.F. When and how to use BRS in bifurcations? EuroIntervention 2015, 11, V185–V187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Peng, X.; Qu, W.; Jia, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yu, B.; Tian, J. Bioresorbable Scaffolds: Contemporary Status and Future Directions. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2020, 7, 589571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indolfi, C.; De Rosa, S.; Colombo, A. Bioresorbable vascular scaffolds—Basic concepts and clinical outcome. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2016, 13, 719–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onuma, Y.; Dudek, D.; Thuesen, L.; Webster, M.; Nieman, K.; Garcia-Garcia, H.M.; Ormiston, J.A.; Serruys, P.W. Five-year clinical and functional multislice computed tomography angiographic results after coronary implantation of the fully resorbable polymeric everolimus-eluting scaffold in patients with de novo coronary artery disease: The ABSORB cohort A trial. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2013, 6, 999–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, G.W.; Kimura, T.; Gao, R.; Kereiakes, D.J.; Ellis, S.G.; Onuma, Y.; Chevalier, B.; Simonton, C.; Dressler, O.; Crowley, A.; et al. Time-Varying Outcomes with the Absorb Bioresorbable Vascular Scaffold During 5-Year Follow-up: A Systematic Meta-analysis and Individual Patient Data Pooled Study. JAMA Cardiol. 2019, 4, 1261–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, S.; Bennett, J.; Nef, H.M.; Webster, M.; Namiki, A.; Takahashi, A.; Kakuta, T.; Yamazaki, S.; Shibata, Y.; Scott, D.; et al. First randomised controlled trial comparing the sirolimus-eluting bioadaptor with the zotarolimus-eluting drug-eluting stent in patients with de novo coronary artery lesions: 12-month clinical and imaging data from the multi-centre, international, BIODAPTOR-RCT. EClinicalMedicine 2023, 65, 102304. [Google Scholar]

- Erlinge, D.; Andersson, J.; Fröbert, O.; Törnerud, M.; Hamid, M.; Kellerth, T.; Grimfjärd, P.; Winnberg, O.; Jurga, J.; Wagner, H.; et al. Bioadaptor implant versus contemporary drug-eluting stent in percutaneous coronary interventions in Sweden (INFINITY-SWEDEHEART): A single-blind, non-inferiority, registry-based, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2024, 404, 1750–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berland, J. The Nile CroCo and Nile PAX stents. EuroIntervention 2015, 11 (Suppl. S5), V149–V150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capodanno, D.; Dipasqua, F.; Tamburino, C. Novel drug-eluting stents in the treatment of de novo coronary lesions. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2011, 7, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Ormiston, J.A.; De Vroey, F.; Webster, M.W.I.; Kandzari, D.E. The Petal dedicated bifurcation stent. EuroIntervention 2010, 6 (Suppl. J), J139–J142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doran, L.M. Medtronic launches latest generation drug-eluting coronary stent system following CE Mark ap-proval. Available online: https://news.medtronic.com/Medtronic-launches-latest-generation-drug-eluting-coronary-stent-system-following-CE-Mark-approval (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Premarket Approval (PMA) Resolute Onyx Zotarolimus-Eluting Coronary Stent System, Onyx Frontier Zotarolimus-Eluting Coronary Stent System. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfpma/pma.cfm?id=P160043S058 (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- TriReme Medical Inc. Receives CE Marking for Antares(TM) Coronary Stent System. Available online: https://www.biospace.com/trireme-medical-inc-receives-ce-marking-for-antares-tm-coronary-stent-system (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Chen, X.-L.; Sheiban, I. Dedicated Bifurcation Stents Strategy. Interv. Cardiol. Rev. 2009, 4, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, R.J.; Bil, J.; Kern, A.; Pawłowski, T. First-in-man study of dedicated bifurcation cobalt-chromium sirolimus-eluting stent BiOSS LIM C®—Three-month results. Kardiol. Pol. 2018, 76, 464–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyxaras, S.A.; Schmitz, T.; Naber, C.K. The STENTYS Self-Apposing® stent. EuroIntervention 2015, 11, V147–V148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blossom, D. Cappella Medical Devices Ltd Announces Excellent Long Term Follow-Up Clinical Data on its Sideguard(R) Technology. Available online: https://www.biospace.com/cappella-medical-devices-ltd-announces-excellent-long-term-follow-up-clinical-data-on-its-sideguard-r-technology (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Tryton Medical, Inc. Receives CE Mark Approval for its Side-Branch Stent. Available online: https://www.biospace.com/tryton-medical-inc-receives-ce-mark-approval-for-its-side-branch-stent (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Premarket Approval (PMA). Tryton Side Branch Stent. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfpma/pma.cfm?ID=320643 (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Rawlins, J.; Din, J.; Talwar, S.; O’Kane, P. AXXESSTM Stent: Delivery Indications and Outcomes. Interv. Cardiol. 2015, 10, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Thiel, J.; Devax, Inc. Receives CE Mark for the AXXESS Drug Eluting Bifurcation Stent. Available online: https://www.biospace.com/devax-inc-receives-ce-mark-for-the-axxess-drug-eluting-bifurcation-stent (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Meredith, I.; Worthley, S.; Whitbourn, R.; Webster, M.; Fitzgerald, P.; Ormiston, J. First-in-human experience with the Medtronic Bifurcation Stent System. EuroIntervention. 2011, 7, 662–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khorsandi, M.; Abizaid, A.; Dani, S.; Bourang, H.; Costa, R.A.; Kar, S.; Makkar, R. The ABS mother-daughter platforms. EuroIntervention. 2015, 11, V151–V152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Major Criteria | Minor Criteria |

|---|---|

|

|

| Trial | Strategy Compared | Follow-Up | MACE | Definite/Probable IST | ISR/TLR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nordic Bifurcation (2006) [31] | Provisional vs. two-stent (Culotte or Crush) | 6 mo | 2.9% vs. 3.4%, p = NS | 0.5% vs. 0%, p = 0.31 | ISR 5.3% vs. 5.1%, p = NS TLR 1.9% vs. 1.0%, p = 0.36 |

| BBK (2008) [32] | Provisional vs. routine T-stenting | 12 mo | 12.9% vs. 11.9%, p = 0.83 | 2% vs. 2%, p = 1.0 | TLR 10.9% vs. 8.9%, p = 0.64 |

| CACTUS (2009) [33] | Provisional vs. two-stent (Crush) | 6 mo | 15% vs. 15.8%, p = 0.95 | 1.1% vs. 1.7% | TLR 6.3% vs. 7.3%, p = 0.83 |

| BBC ONE (2010) [34] | Provisional vs. two-stent (Culotte or Crush) | 9 mo | 8% vs. 15.2%, p = 0.009 | 0.4% vs. 2.0% | TLR 5.6% vs. 6.8%, p = NS |

| PERFECT 2015 [35] | Provisional vs. two-stent (Crush) | 12 mo | 18.5% vs. 17.8%, p = 0.85 | 0% vs. 0.5%, p = 0.32 | ISR 11% vs. 8.4%, p = 0.44 TLR 3.4% vs. 1.9%, p = 0.33 |

| EBC TWO 2016 [36] | Provisional vs. two-stent (Culotte) in non-LM | 12 mo | 7.7% vs. 10.3%, p = 0.53 | 0.97% vs. 2.06%, p = 0.357 | TVR 2.9% vs. 1.0%, p = 0.621 |

| NORDIC IV 2020 [37] | Provisional vs. two-stent (Culotte) | 24 mo | 12.9% vs. 8.4%, p = 0.12 | 2.8% vs. 2.2%, p = 0.7 | TLR 9.2% vs. 6.2%, p = 0.23 |

| Trial | Strategy Compared | Follow-Up | MACE | Definite/Probable IST | ISR/TLR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DKCRUSH-I (2008) [40] | Classical vs. DK crush | 8 mo | 24.4% vs. 11.4%, p = 0.02 | 3.2% vs. 1.3%, p = 1.0 | 22.6% vs. 9%, p = 0.03 |

| DKCRUSH-II (2011) [41] | Provisional vs. two-stent (DK crush) in non-LM | 12 mo | 17.3% vs. 10.3%, p = 0.07 | 1.1% vs. 2.7%, p = 0.449 | TLR 13% vs. 4.3%, p = 0.005 |

| Trial | Strategy Compared | Follow-Up | MACE | Definite/Probable IST | ISR/TLR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DKCRUSH-III (2015) [43] | DK crush vs. Culotte (LM bifurcation) in unprotected LM | 36 mo | 8.2% vs. 23.7%, p < 0.001) | 0.5% vs. 3.9%, p = 0.02 | TLR 5.8% vs. 18.8%, p < 0.001 |

| DKCRUSH-V (2017) [14] | Provisional vs. two-stent (DK crush-LM bifurcation) in distal LM | 12 mo | 10.7% vs. 5%, p = 0.02 | 3.3% vs. 0.4%, p = 0.02 | TLR 7.9% vs. 3.8%, p = 0.06 |

| DEFINITION II (2020) [13] | Provisional vs. two-stent (DK crush) in complex bifurcations | 12 mo | 11.4% vs. 6.1%, p = 0.019 | 2.5% vs. 1.2%, p = 0.244 | TLR 5.5% vs. 2.4%, p = 0.049 |

| EBC MAIN (2021) [44] | Provisional vs. two-stent (Culotte or TAP) in LM | 12 mo | 14.7% vs. 17.7%, p = 0.34 | 1.7% vs. 1.3%, p = 0.9 | TLR 6.1% vs. 9.3%, p = 0.16 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Damrongwatanasuk, R.; Pollanen, S.; Bae, J.Y.; Wen, J.; Nanna, M.G.; Damluji, A.A.; Mamas, M.A.; Hanna, E.B.; Hu, J.-R. Coronary Bifurcation PCI—Part II: Advanced Considerations. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2025, 12, 439. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd12110439

Damrongwatanasuk R, Pollanen S, Bae JY, Wen J, Nanna MG, Damluji AA, Mamas MA, Hanna EB, Hu J-R. Coronary Bifurcation PCI—Part II: Advanced Considerations. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease. 2025; 12(11):439. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd12110439

Chicago/Turabian StyleDamrongwatanasuk, Rongras, Sara Pollanen, Ju Young Bae, Jason Wen, Michael G. Nanna, Abdulla A. Damluji, Mamas A Mamas, Elias B. Hanna, and Jiun-Ruey Hu. 2025. "Coronary Bifurcation PCI—Part II: Advanced Considerations" Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease 12, no. 11: 439. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd12110439

APA StyleDamrongwatanasuk, R., Pollanen, S., Bae, J. Y., Wen, J., Nanna, M. G., Damluji, A. A., Mamas, M. A., Hanna, E. B., & Hu, J.-R. (2025). Coronary Bifurcation PCI—Part II: Advanced Considerations. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease, 12(11), 439. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd12110439