Effectiveness of a Modified Administration Protocol for the Medical Treatment of Feline Pyometra

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Case Description

3. Outcome and Follow-Up

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hagman, R. Pyometra in Small Animals 2.0. Vet. Clin. Small Anim. Pract. 2022, 52, 631–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pisu, M.C.; Andolfatto, A.; Veronesi, M.C. Pyometra in a six-month-old nulliparous golden hamster (Mesocricetus auratus) treated with aglepristone. Vet. Q. 2012, 32, 179–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Degerfeld, M.M.; Banchi, P.; Quaranta, G. Successful Treatment of pyometra caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in a rabbit. Top. Companion Anim. Med. 2020, 41, 100473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagman, R.; Holst, B.S.; Möller, L.; Egenvall, A. Incidence of pyometra in Swedish insured cats. Theriogenology 2014, 82, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiessing, J.; Thomson, K.S. Treatment of feline pyometra with dinoprost. N. Z. Vet. J. 1980, 28, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Faria, V.P.; Norsworthy, G.D. Pyometra in a 13-year-old neutered queen. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2008, 10, 185–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nak, D.; Nak, Y.; Tuna, B. Follow-up examinations after medical treatment of pyometra in cats with the progesterone-antagonist aglepristone. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2009, 11, 499–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollinshead, F.; Krekeler, N. Pyometra in the queen: To spay or not to spay? J. Feline Med. Surg. 2016, 18, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misk, T.N.; EL-sherry, T.M. Pyometra in Cats: Medical Versus Surgical Treatment. J. Curr. Vet. Res. 2020, 2, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agudelo, C.F. Cystic endometrial hyperplasia-pyometra complex in cats. A review. Vet. Q. 2005, 27, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bosschere, H.; Ducatelle, R.; Vermeirsch, H.; Van Den Broeck, W.; Coryn, M. Cystic endometrial hyperplasia-pyometra complex in the bitch: Should the two entities be disconnected? Theriogenology 2001, 55, 1509–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, C.E.; De Carli, S.; Weber, M.N.; Fonseca, A.C.; Tagliari, N.J.; Foresti, L.; Cibulski, S.P.; Mayer, F.Q.; Canal, C.W.; Siqueira, F.M. Insights on the genetic features of endometrial pathogenic Escherichia coli strains from pyometra in companion animals: Improving the knowledge about pathogenesis. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2020, 85, 104453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verstegen, J.; Onclin, K. The mucometra–pyometra complex in the queen. In Proceedings of the North American Veterinary Conference, Orlando, FL, USA, 7–11 January 2006; pp. 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Klainbart, S.; Agi, L.; Bdolah-Abram, T.; Kelmer, E.; Aroch, I. Clinical, laboratory, and hemostatic findings in cats with naturally occurring sepsis. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2017, 251, 1025–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, S.W.; Pacchiana, P.D. Uterine torsion and metabolic abnormalities in a cat with a pyometra. Can. Vet. J. 2008, 49, 398. [Google Scholar]

- Vilhena, H.; Figueiredo, M.; Cerón, J.J.; Pastor, J.; Miranda, S.; Craveiro, H.; Pires, M.A.; Tecles, F.; Rubio, C.P.; Dabrowski, R.; et al. Acute phase proteins and antioxidant responses in queens with pyometra. Theriogenology 2018, 115, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fieni, F.; Topie, E.; Gogny, A. Medical treatment for pyometra in dogs. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2014, 49, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Mitacek, M.C.; Stornelli, M.C.; Tittarelli, C.M.; Nuñez Favre, R.; de la Sota, R.L.; Stornelli, M.A. Cloprostenol treatment of feline open-cervix pyometra. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2014, 16, 177–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verstegen, J.P.; Onclin, K.; Silva, L.D.; Donnay, I. Abortion induction in the cat using prostaglandin F2 alpha and a new anti-prolactinic agent, cabergoline. J. Reprod. Fertil. Suppl. 1993, 47, 411–417. [Google Scholar]

- Gogny, A.; Fiéni, F. Aglepristone: A review on its clinical use in animals. Theriogenology 2016, 85, 555–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goericke-Pesch, S. Reproduction control in cats: New developments in non-surgical methods. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2010, 12, 539–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aglepristone. Scientific Update 2010. Virbac. Available online: https://es.virbac.com/files/live/sites/virbac-es/files/Elementos%20p%C3%A1ginas/amvac/Archivos/Aglepristone%20Scientific%20update.pdf (accessed on 22 August 2022).

- Contri, A.; Gloria, A.; Carluccio, A.; Pantaleo, S.; Robbe, D. Effectiveness of a modified administration protocol for the medical treatment of canine pyometra. Vet. Res. Commun. 2015, 39, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faya, M.; Carranza, A.; Priotto, M.; Graiff, D.; Zurbriggen, G.; Diaz, J.D.; Gobello, C. Long-term melatonin treatment prolongs interestrus, but does not delay puberty, in domestic cats. Theriogenology 2011, 75, 1750–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goericke-Pesch, S.; Georgiev, P.; Atanasov, A.; Albouy, M.; Navarro, C.; Wehrend, A. Treatment of queens in estrus and after estrus with a GnRH-agonist implant containing 4.7 mg deslorelin; hormonal response, duration of efficacy, and reversibility. Theriogenology 2013, 79, 640–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco, P.G.; Rube, A.; López Merlo, M.; Batista, P.R.; Arioni, S.; López Knudsen, I.; Tórtora, M.; Gobello, C. Uterine two-dimensional and Doppler ultrasonographic evaluation of feline pyometra. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2018, 53, 70–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fieni, F. Clinical evaluation of the use of aglepristone, with or without cloprostenol, to treat cystic endometrial hyperplasia-pyometra complex in bitches. Theriogenology 2006, 66, 1550–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fieni, F.; Martal, J.; Marnet, P.G.; Siliart, B.; Guittot, F. Clinical, biological and hormonal study of mid-pregnancy termination in cats with aglepristone. Theriogenology 2006, 66, 1721–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philibert, D. RU 46534 Affinite Relative de Liaisonpourlesrecepteurssteroidiens-Activite Antiprogesterone In Vivo. Rapportd’etude Interne Roussel Uclaf. 1994. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=it&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Philibert+D.+RU+46534.+Affinite%C2%B4+relative+de+liaison+pour+les+re%C2%B4cepteurs+ste%C2%B4ro%C4%B1%C2%A8diens%E2%80%94activite%C2%B4+antiprogeste%C2%B4rone+in+vivo.+Rapport+d%E2%80%99e%C2%B4tude+interne+Roussel+Uclaf%3B+1994.&btnG= (accessed on 27 August 2022).

- Marino, G.; Pugliese, M.; Pecchia, F.; Garufi, G.; Lupo, V.; Di Giorgio, S.; Sfacteria, A. Conservative treatments for feline fibroadenomatous changes of the mammary gland. Open Vet. J. 2021, 11, 680–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagman, R.; Karlstam, E.; Persson, S.; Kindahl, H. Plasma PGF2α metabolite levels in cats with uterine disease. Theriogenology 2009, 72, 1180–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogny, A.; Mallem, Y.; Destrumelle, S.; Thorin, C.; Desfontis, J.C.; Gogny, M.; Fiéni, F. In vitro comparison of myometrial contractility induced by aglepristone-oxytocin and aglepristone-PGF2alpha combinations at different stages of the estrus cycle in the bitch. Theriogenology 2010, 74, 1531–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melandri, M.; Veronesi, M.C.; Pisu, M.C.; Majolino, G.; Alonge, S. Fertility outcome after medically treated pyometra in dogs. J. Vet. Sci. 2019, 20, e39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ros, L.; Holst, B.S.; Hagman, R. A retrospective study of bitches with pyometra, medically treated with aglepristone. Theriogenology 2014, 82, 1281–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobello, C.; Castex, G.; Klima, L.; Rodríguez, R.; Corrada, Y. A study of two protocols combining aglepristone and cloprostenol to treat open cervix pyometra in the bitch. Theriogenology 2003, 60, 901–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trasch, K.; Wehrend, A.; Bostedt, H. Follow-up examinations of bitches after conservative treatment of pyometra with the antigestagen aglepristone. J. Vet. Med. Ser. A 2003, 50, 375–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Mitacek, M.G.; Bonaura, M.C.; Praderio, R.G.; Favre, R.N.; de la Sota, R.L.; Stornelli, M.A. Progesterone and ultrasonographic changes during aglepristone or cloprosternol treatment in queens at 21 to 22 or 35 to 38 days of pregnancy. Theriogenology 2017, 88, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galac, S.; Kooistra, H.S.; Dieleman, S.J.; Cestnik, V.; Okkens, A.C. Effects of aglepristone, a progesterone receptor antagonist, administered during the early luteal phase in non-pregnant bitches. Theriogenology 2004, 62, 494–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutzler, M.A. Alternative methods for feline fertility control: Use of melatonin to suppress reproduction. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2015, 17, 753–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Animals | Month of Referral | Age | Breed | Referred For | History |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 | March | 9 months | Domestic Short Air | General illness | Renal damage |

| Patient 2 | May | 16 months | Main Coon | Suspicion of vaginitis | Recent mating |

| Patient 3 | April | 23 months | Siamese | Pregnancy diagnosis | Recent mating |

| Patient 4 | May | 13 months | Bengal | Pregnancy diagnosis | Recent mating |

| Patient 5 | July | 20 months | Main Coon | Vaginal Discharge | Recent mating |

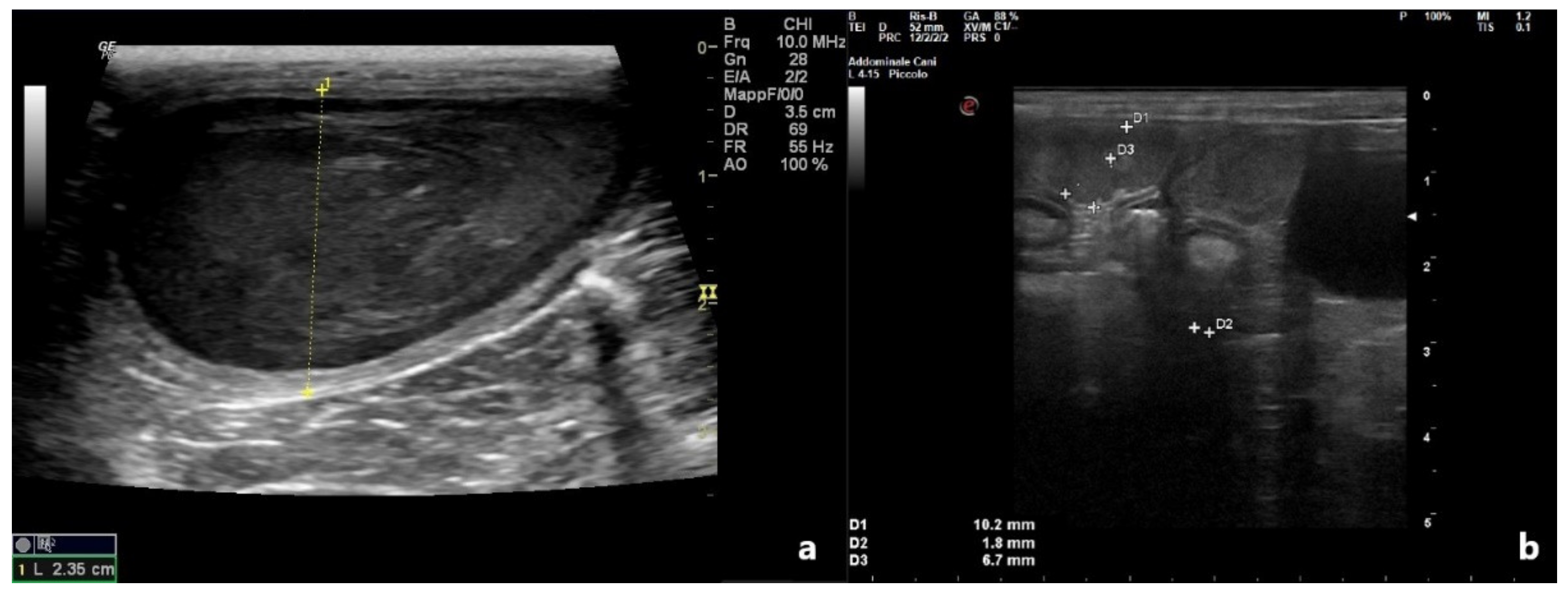

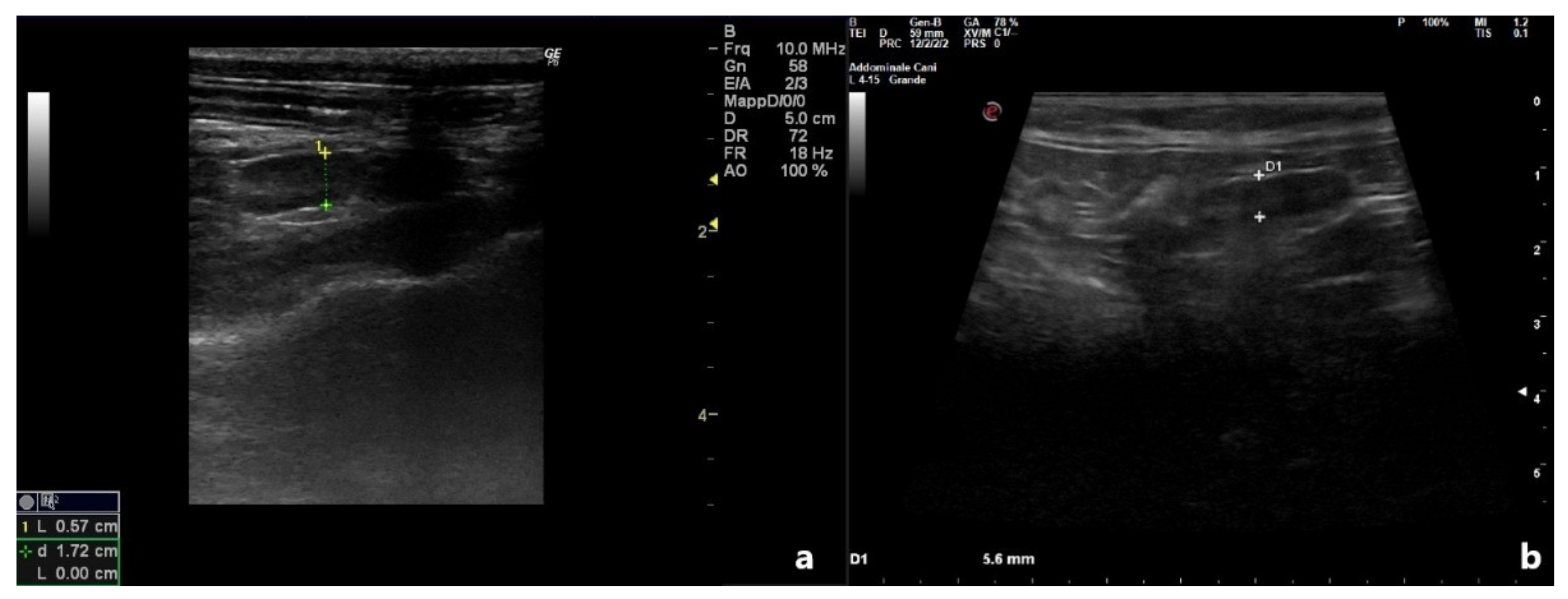

| Uterine Diameter (cm) | Uterine Wall (cm) | Luminal Collection | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D0 | D10 | D0 | D10 | D0 | D10 | |

| Patient 1 | 0.75 | 0.49 | 0.2 | 0.05 | Hypoecoic | No |

| Patient 2 | 2.35 | 0.57 | 0.3 | 0.10 | Heterogeneous | No |

| Patient 3 | 0.41 | 0.23 | 0.1 | 0.1 | Anechoic | No |

| Patient 4 | 1.02 | 0.56 | 0.18 | 0.10 | Anechoic | No |

| Patient 5 | 0.80 | 0.37 | 0.15 | 0.10 | Hypoecoic | No |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Attard, S.; Bucci, R.; Parrillo, S.; Pisu, M.C. Effectiveness of a Modified Administration Protocol for the Medical Treatment of Feline Pyometra. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 517. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci9100517

Attard S, Bucci R, Parrillo S, Pisu MC. Effectiveness of a Modified Administration Protocol for the Medical Treatment of Feline Pyometra. Veterinary Sciences. 2022; 9(10):517. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci9100517

Chicago/Turabian StyleAttard, Simona, Roberta Bucci, Salvatore Parrillo, and Maria Carmela Pisu. 2022. "Effectiveness of a Modified Administration Protocol for the Medical Treatment of Feline Pyometra" Veterinary Sciences 9, no. 10: 517. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci9100517

APA StyleAttard, S., Bucci, R., Parrillo, S., & Pisu, M. C. (2022). Effectiveness of a Modified Administration Protocol for the Medical Treatment of Feline Pyometra. Veterinary Sciences, 9(10), 517. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci9100517