The Beneficial Effects of Guanidinoacetic Acid as a Functional Feed Additive: A Possible Approach for Poultry Production

Simple Summary

Abstract

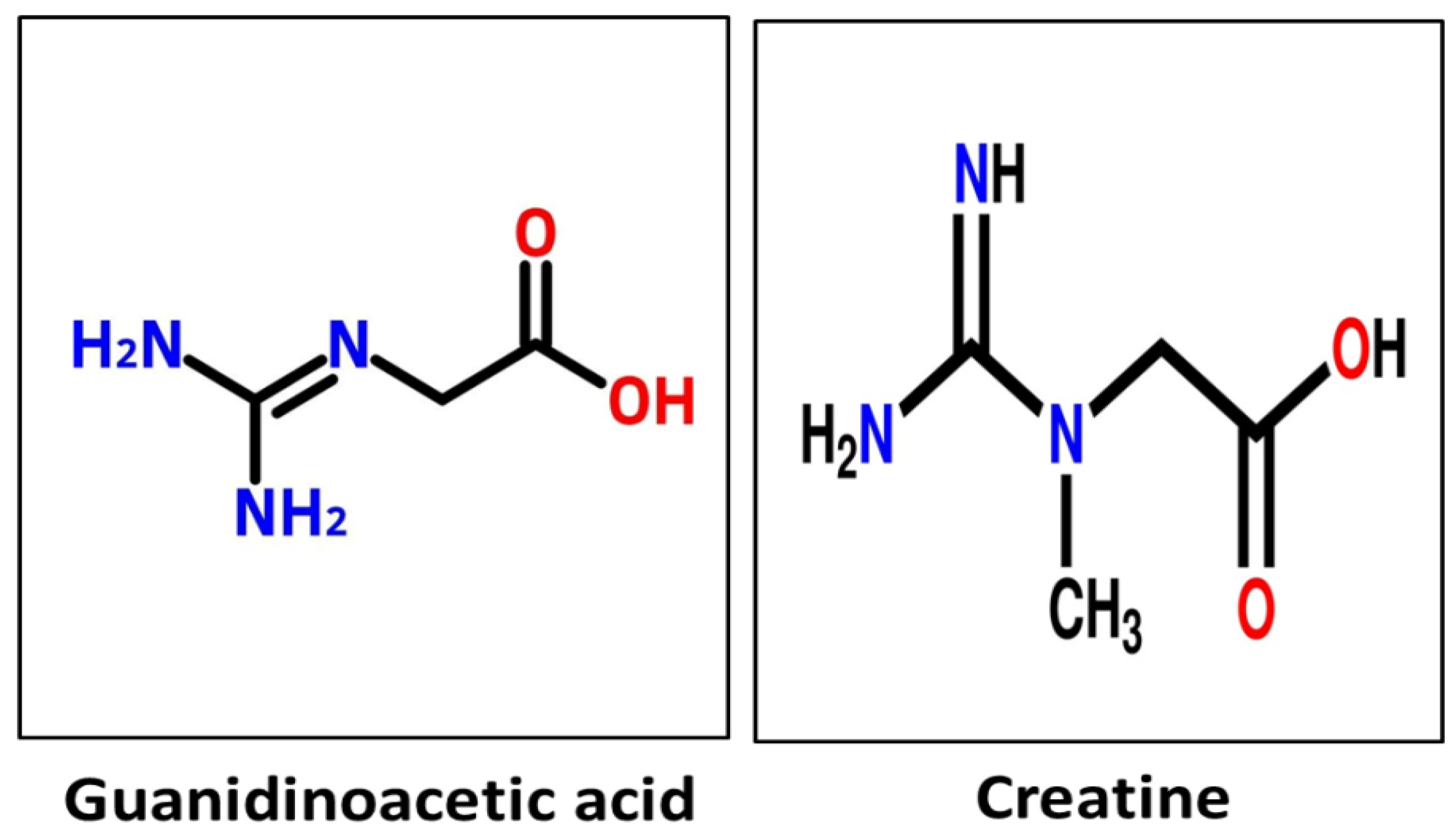

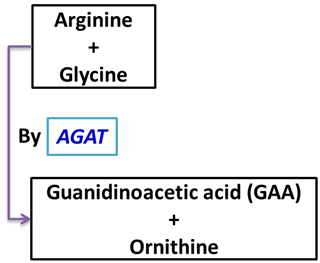

1. Introduction

2. Comprehensive Methodology for Review

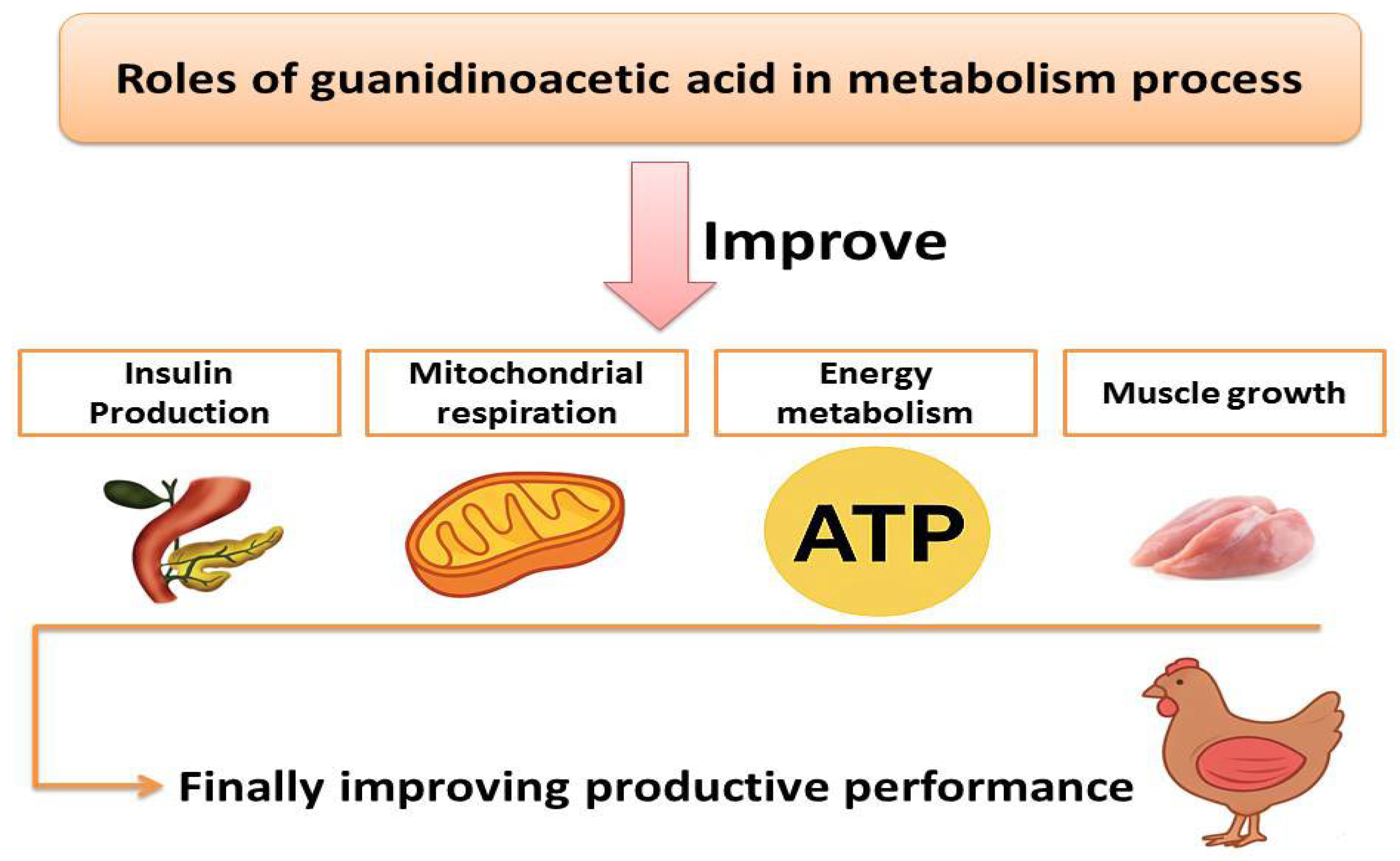

3. Guanidinoacetic Acid and Its Effects on Metabolic Processes, Energy Utilization, and Nutrient Digestibility

4. Effect of GAA on Blood Parameters

5. Effect of GAA on Lipid Profile

6. Effect of GAA on Antioxidant Indices

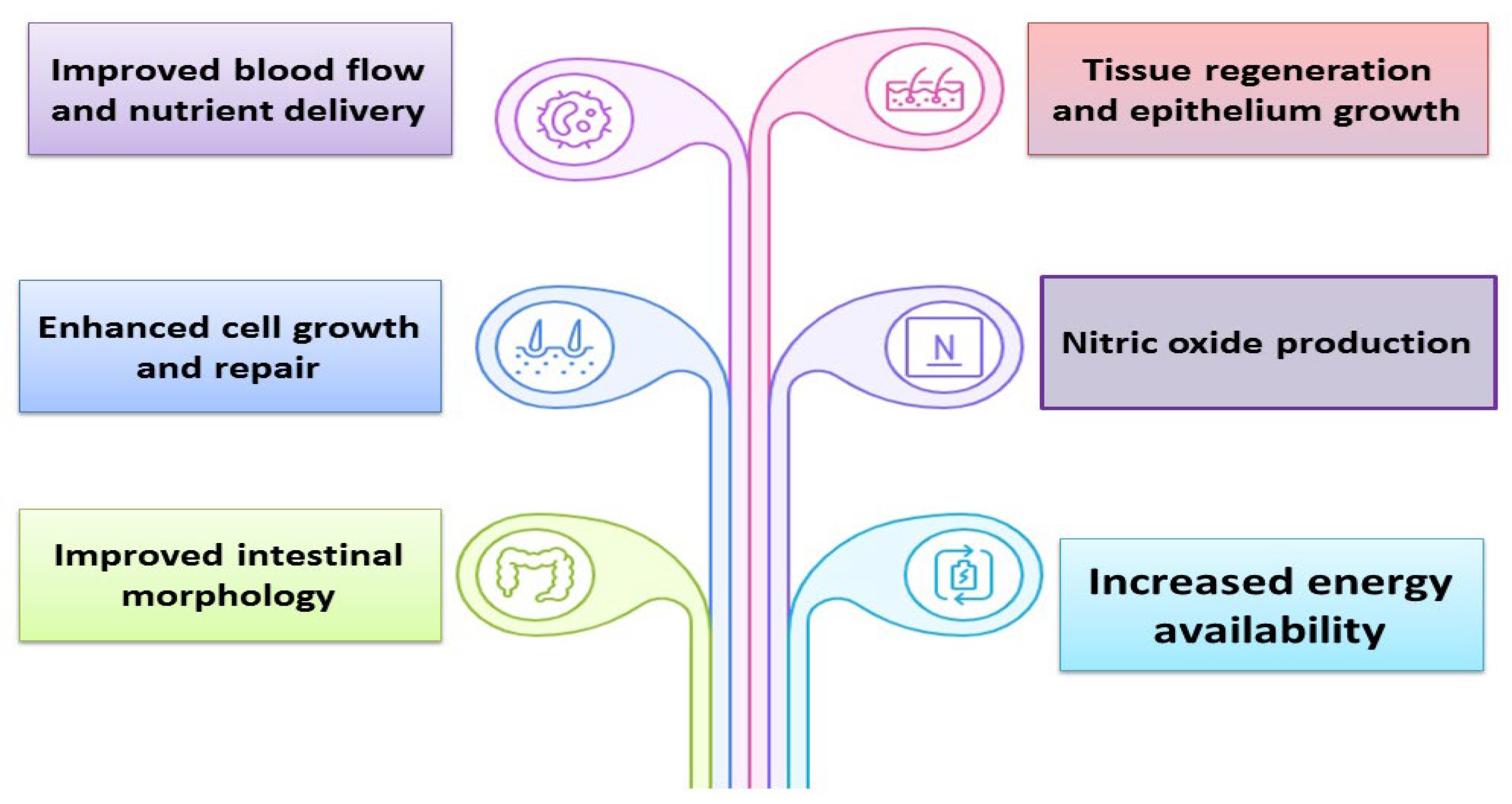

7. Effect of GAA on Immunity

8. Effect of GAA on Gut Microbiota

9. Effect of GAA on Intestinal Integrity

10. Effect of GAA on Reproduction

11. Effect of GAA on Egg Quality

12. Effect of GAA on Growth Performance

13. Strengths, Limitations, and Future Prospects

14. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Asiriwardhana, M.; Bertolo, R.F. Guanidinoacetic acid supplementation: A narrative review of its metabolism and effects in swine and poultry. Front. Anim. Sci. 2022, 3, 972868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostojic, S.M. Guanidinoacetic acid as a performance-enhancing agent. Amino Acids 2016, 48, 1867–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Aziz, A.A.; Alsenosy, A.E.W.; Puvača, N.; Tufarelli, V. Guanidinoacetic acid as a functional additive in broiler nutrition: Insights into performance, carcass, antioxidant capacity, and health. World’s Poult. Sci. J. 2025, 81, 855–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, H.A.; Azizollahi, M.; Lahroudi, M.A.; Taherpour, K.; Hajkhodadadi, I.; Akhavan-Salamat, H.; Rahmatnejad, E. Guanidinoacetic acid in laying hen diets with varying dietary energy: Productivity, antioxidant status, yolk fatty acid profile, hepatic lipid metabolism, and gut health. Poult. Sci. 2025, 104, 105159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, W.; Li, J.; Xing, T.; Zhang, L.; Gao, F. Effects of guanidinoacetic acid and complex antioxidant supplementation on growth performance, meat quality, and antioxidant function of broiler chickens. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2021, 101, 3961–3968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, D.H. Advances in protein–amino acid nutrition of poultry. Amino Acids 2009, 37, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Gu, C.; Hu, S.; Li, B.; Zeng, X.; Yin, J. Dietary guanidinoacetic acid supplementation improved carcass characteristics, meat quality and muscle fibre traits in growing–finishing gilts. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2020, 104, 1454–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michiels, J.; Maertens, L.; Buyse, J.; Lemme, A.; Rademacher, M.; Dierick, N.A.; De Smet, S. Supplementation of guanidinoacetic acid to broiler diets: Effects on performance, carcass characteristics, meat quality, and energy metabolism. Poult. Sci. 2012, 91, 402–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilger, R.N.; Bryant-Angeloni, K.; Payne, R.L.; Lemme, A.; Parsons, C.M. Dietary guanidino acetic acid is an efficacious replacement for arginine for young chicks. Poult. Sci. 2013, 92, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyss, M.; Kaddurah-Daouk, R. Creatine and creatinine metabolism. Physiol. Rev. 2000, 80, 1107–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nain, S.; Ling, B.; Alcorn, J.; Wojnarowicz, C.M.; Laarveld, B.; Olkowski, A.A. Biochemical factors limiting myocardial energy in a chicken genotype selected for rapid growth. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2008, 149, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majdeddin, M.; Braun, U.; Lemme, A.; Golian, A.; Kermanshahi, H.; De Smet, S.; Michiels, J. Guanidinoacetic acid supplementation improves feed conversion in broilers subjected to heat stress associated with muscle creatine loading and arginine sparing. Poult. Sci. 2020, 99, 4442–4453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.Y.; Xing, T.; Li, J.L.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, Y.; Gao, F. Guanidinoacetic acid supplementation improves intestinal morphology, mucosal barrier function of broilers subjected to chronic heat stress. J. Anim. Sci. 2023, 101, skac355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadipour, B.; Khajali, F.; Sharifi, M.R. Effect of guanidinoacetic acid supplementation on growth performance and gut morphology in broiler chickens. Poult. Sci. J. 2018, 6, 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- DeGroot, A.A.; Braun, U.; Dilger, R.N. Guanidinoacetic acid is efficacious in improving growth performance and muscle energy homeostasis in broiler chicks fed arginine-deficient or arginine-adequate diets. Poult. Sci. 2019, 98, 2896–2905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portocarero, N.; Braun, U. The physiological role of guanidinoacetic acid and its relationship with arginine in broiler chickens. Poult. Sci. 2021, 100, 101203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ncho, C.M.; Gupta, V.; Choi, Y.H. Effects of dietary glutamine supplementation on heat-induced oxidative stress in broiler chickens: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, Z.; Li, J. Effects of Guanidine Acetic Acid on the Growth and Slaughter Performance, Meat Quality, Antioxidant Capacity, and Cecal Microbiota of Broiler Chickens. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 550. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Bian, J.; Xing, T.; Zhao, L.; Li, J.; Zhang, L.; Gao, F. Effects of guanidinoacetic acid supplementation on growth performance, hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis, and immunity of broilers challenged with chronic heat stress. Poult. Sci. 2023, 102, 103114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolo, R.F.; McBreairty, L.E. The nutritional burden of methylation reactions. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2013, 16, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeGroot, A.A.; Braun, U.; Dilger, R.N. Efficacy of guanidinoacetic acid on growth and muscle energy metabolism in broiler chicks receiving arginine-deficient diets. Poult. Sci. 2018, 97, 890–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tossenberger, J.; Rademacher, M.; Németh, K.; Halas, V.; Lemme, A.J.P.S. Digestibility and metabolism of dietary guanidino acetic acid fed to broilers. Poult. Sci. 2016, 95, 2058–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fosoul, S.S.A.S.; Azarfar, A.; Gheisari, A.; Khosravinia, H. Energy utilisation of broiler chickens in response to guanidinoacetic acid supplementation in diets with various energy contents. Br. J. Nutr. 2018, 120, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khajali, F.; Lemme, A.; Rademacher-Heilshorn, M. Guanidinoacetic acid as a feed supplement for poultry. World’s Poult. Sci. J. 2020, 76, 270–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majdeddin, M.; Golian, A.; Kermanshahi, H.; Michiels, J.; De Smet, S. Effects of methionine and guanidinoacetic acid supplementation on performance and energy metabolites in breast muscle of male broiler chickens fed corn-soybean diets. Br. Poult. Sci. 2019, 60, 554–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostojic, S.M. Cellular bioenergetics of guanidinoacetic acid: The role of mitochondria. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2015, 47, 369–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boroumandnia, Z.; Khosravinia, H.; Masouri, B.; Parizadian Kavan, B. Effects of dietary supplementation of guanidinoacetic acid on physiological response of broiler chicken exposed to repeated lactic acid injection. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2021, 20, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostojic, S.M. An alternative mechanism for guanidinoacetic acid to affect methylation cycle. Med. Hypotheses 2014, 83, 847–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosnan, J.T.; Brosnan, M.E. Creatine: Endogenous metabolite, dietary, and therapeutic supplement. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2007, 27, 241–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, S.; Al-Sagan, A.A.; Abdellatif, H.A.; Prince, A.; El-Banna, R. Effects of guanidinoacetic acid supplementation on zootechnical performance and some biometric indices in broilers challenged with T3-Hormone. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2021, 20, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majdeddin, M.; Braun, U.; Lemme, A.; Golian, A.; Kermanshahi, H.; De Smet, S.; Michiels, J. Effects of feeding guanidinoacetic acid on oxidative status and creatine metabolism in broilers subjected to chronic cyclic heat stress in the finisher phase. Poult. Sci. 2023, 102, 102653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mousavi, S.N.; Afsar, A.; Lotfollahian, H. Effects of guanidinoacetic acid supplementation to broiler diets with varying energy contents. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2013, 22, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raei, A.; Karimi, A.; Sadeghi, A. Performance, antioxidant status, nutrient retention and serum profile responses of laying Japanese quails to increasing addition levels of dietary guanidinoacetic acid. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2020, 19, 75–85. [Google Scholar]

- Wallimann, T.; Tokarska-Schlattner, M.; Schlattner, U. The creatine kinase system and pleiotropic effects of creatine. Amino Acids 2011, 40, 1271–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, K.M.; Mello, H.H.D.C.; Café, M.B.; Arnhold, E.; Xavier, H.P.; de Oliveira, H.F.; Mascarenhas, A.G. Effect of dietary inclusion of guanidinoacetic acid on broiler performance. Revista Colomb. Cienc. Pec. 2021, 34, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizollahi, M.; Ghasemi, H.A.; Foroudi, F.; Hajkhodadadi, I. Effect of guanidinoacetic acid on performance, egg quality, yolk fatty acid composition, and nutrient digestibility of aged laying hens fed diets with varying substitution levels of corn with low-tannin sorghum. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 103297. [Google Scholar]

- Córdova-Noboa, H.A.; Oviedo-Rondón, E.O.; Sarsour, A.H.; Barnes, J.; Sapcota, D.; López, D.; Braun, U. Effect of guanidinoacetic acid supplementation on live performance, meat quality, pectoral myopathies and blood parameters of male broilers fed corn-based diets with or without poultry by-products. Poult. Sci. 2018, 97, 2494–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeGroot, A. Efficacy of Dietary Guanidinoacetic Acid in Broiler Chicks. Master’s Thesis, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Champaign, IL, USA, 2015; p. 397184. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/2142/72902 (accessed on 25 December 2024).

- Hu, X.; Wang, Y.; Sheikhahmadi, A.; Li, X.; Buyse, J.; Lin, H.; Song, Z. Effects of glucocorticoids on lipid metabolism and AMPK in broiler chickens’ liver. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2019, 232, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmawati, D.; Hanim, C. Supplementation of guanidinoacetic acid in feed with different levels of protein on intestinal histomorphology, serum biochemistry, and meat quality of broiler. J. Indones. Trop. Anim. Agric. 2022, 4, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaa, M.; Abdel Razek, A.H.; Tony, M.A.; Yassin, A.M.; Warda, M.; Awad, M.A.; Bawish, B.M. Guanidinoacetic acid supplementation and stocking density effects on broiler performance: Behavior, biochemistry, immunity, and small intestinal histomorphology. Acta Vet. Scand. 2024, 66, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, M.; Ghasemi, H.A.; Hajkhodadadi, I.; Farahani, A.H.K. Efficacy of guanidinoacetic acid at different dietary crude protein levels on growth performance, stress indicators, antioxidant status, and intestinal morphology in broiler chickens subjected to cyclic heat stress. Anim. Feed. Sci. Technol. 2019, 254, 114208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Jiang, F.; Yuan, Q.; Yan, R.; Zhuang, S. Effects of guanidinoacetic acid on performance and antioxidant capacity in Cherry Valley ducks. J. Nanjing Agric. Univ. 2016, 39, 269–274. [Google Scholar]

- Nasiroleslami, M.; Torki, M.; Saki, A.A.; Abdolmohammadi, A.R. Effects of dietary guanidinoacetic acid and betaine supplementation on performance, blood biochemical parameters and antioxidant status of broilers subjected to cold stress. J. Appl. Anim. Res. 2018, 46, 1016–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebeid, T.A.; Aljabeili, H.S.; Al-Homidan, I.H.; Volek, Z.; Barakat, H. Ramifications of heat stress on rabbit production and role of nutraceuticals in alleviating its negative impacts: An updated review. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodambashi Emami, N.; Golian, A.; Rhoads, D.D.; Danesh Mesgaran, M. Interactive effects of temperature and dietary supplementation of arginine or guanidinoacetic acid on nutritional and physiological responses in male broiler chickens. Br. Poult. Sci. 2017, 58, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhoads, J.M.; Chen, W.; Gookin, J.; Wu, G.Y.; Fu, Q.; Blikslager, A.T.; Romer, L.H. Arginine stimulates intestinal cell migration through a focal adhesion kinase dependent mechanism. Gut 2004, 53, 514–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Abdullatif, A.A.; Azzam, M.M.; Samara, E.M.; Al-Badwi, M.A.; Dong, X.; Abdel-Moneim, A.M.E. Assessing the Influence of Guanidinoacetic Acid on Growth Performance, Body Temperature, Blood Metabolites, and Intestinal Morphometry in Broilers: A Comparative Sex-Based Experiment. Animals 2024, 14, 1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, C.; Ding, Y.; He, Q.; Azzam, M.M.M.; Lu, J.J.; Zou, X.T. L-arginine upregulates the gene expression of target of rapamycin signaling pathway and stimulates protein synthesis in chicken intestinal epithelial cells. Poult. Sci. 2015, 94, 1043–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez de la Lastra, J.M.; Curieses Andrés, C.M.; Andrés Juan, C.; Plou, F.J.; Pérez-Lebeña, E. Hydroxytyrosol and arginine as antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and immunostimulant dietary supplements for COVID-19 and long COVID. Foods 2023, 12, 1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Bin, P.; Tao, S.; Zhu, G.; Wu, Z.; Cheng, W.; Wei, H. Evaluation of the mechanisms underlying amino acid and microbiota interactions in intestinal infections using germ-free animals. Infect. Microbes Dis. 2021, 3, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceylan, N.; Koca, S.; Adabi, S.G.; Kahraman, N.; Bhaya, M.N.; Bozkurt, M.F. Effects of dietary energy level and guanidino acetic acid supplementation on growth performance, carcass quality and intestinal architecture of broilers. Czech J. Anim. Sci. 2021, 66, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, H.T.; Swick, R.A. New insights into arginine and arginine-sparing effects of guanidinoacetic acid and citrulline in broiler diets. World’s Poult. Sci. J. 2021, 77, 753–773. [Google Scholar]

- Sharideh, H.; Esmaeile Neia, L.; Zaghari, M.; Zhandi, M.; Akhlaghi, A.; Lotfi, L. Effect of feeding guanidinoacetic acid and L-arginine on the fertility rate and sperm penetration in the perivitelline layer of aged broiler breeder hens. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2016, 100, 316–322. [Google Scholar]

- Tapeh, R.S.; Zhandi, M.; Zaghari, M.; Akhlaghi, A. Effects of guanidinoacetic acid diet supplementation on semen quality and fertility of broiler breeder roosters. Theriogenology 2017, 89, 178–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reicher, N.; Epstein, T.; Gravitz, D.; Cahaner, A.; Rademacher, M.; Braun, U.; Uni, Z. From broiler breeder hen feed to the egg and embryo: The molecular effects of guanidinoacetate supplementation on creatine transport and synthesis. Poult. Sci. 2020, 99, 3574–3582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murakami, A.E.; Rodrigueiro, R.J.B.; Santos, T.C.; Ospina-Rojas, I.C.; Rademacher, M. Effects of dietary supplementation of meat-type quail breeders with guanidinoacetic acid on their reproductive parameters and progeny performance. Poult. Sci. 2014, 93, 2237–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salah, A.S.; Ahmed-Farid, O.A.; El-Tarabany, M.S. Effects of Guanidinoacetic acid supplements on laying performance, egg quality, liver nitric oxide and energy metabolism in laying hens at the late stage of production. J. Agric. Sci. 2020, 158, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimenta, J.G.; Barbosa, H.J.; Fraga, M.G.; Triginelli, M.V.; Costa, B.T.; Ferreira, M.A.; Lara, L.J. Inclusion of guanidinoacetic acid in the diet of laying hens at late phase of feeding. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2023, 63, 596–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khakran, G.; Chamani, M.; Foroudi, F.; Sadeghi, A.A.; Afshar, M.A. Effect of guanidine acetic acid addition to corn-soybean meal based diets on productive performance, blood biochemical parameters and reproductive hormones of laying hens. Kafkas Univ. Vet. Fak. Derg. 2018, 24, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manwar, S.J.; Moudgal, R.P.; Sastry, K.V.H.; Mohan, J.; Tyagi, J.B.S.; Raina, R. Role of nitric oxide in ovarian follicular development and egg production in Japanese quail (Coturnix coturnix japonica). Theriogenology 2006, 65, 1392–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyanga, V.A.; Xin, Q.; Sun, M.; Zhao, J.; Wang, X.; Jiao, H.; Lin, H. Research Note: Effects of dietary L-arginine on the production performance and gene expression of reproductive hormones in laying hens fed low crude protein diets. Poult. Sci. 2022, 101, 101816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gladwin, M.T.; Raat, N.J.; Shiva, S.; Dezfulian, C.; Hogg, N.; Kim-Shapiro, D.B.; Patel, R.P. Nitrite as a vascular endocrine nitric oxide reservoir that contributes to hypoxic signaling, cytoprotection, and vasodilation. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2006, 291, H2026–H2035. [Google Scholar]

- Vlčková, J.; Tůmová, E.; Míková, K.; Englmaierová, M.; Okrouhlá, M.; Chodová, D. Changes in the quality of eggs during storage depending on the housing system and the age of hens. Poult. Sci. 2019, 98, 6187–6193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaman, F.; Acikan, I.; Dundar, S.; Simsek, S.; Gul, M.; Ozercan, I.H.; Sahin, K. Dietary arginine silicate inositol complex increased bone healing: Histologic and histomorphometric study. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2016, 10, 2081–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieboldt, M.A.; Halle, I.; Frahm, J.; Schrader, L.; Weigend, S.; Preisinger, R.; Dänicke, S. Effects of long-term graded L-arginine supply on growth development, egg laying and egg quality in four genetically diverse purebred layer lines. J. Poult. Sci. 2015, 53, 8–21. [Google Scholar]

- Sahin, K.; Orhan, C.; Tuzcu, M.; Hayirli, A.; Komorowski, J.R.; Sahin, N. Effects of dietary supplementation of arginine-silicate-inositol complex on absorption and metabolism of calcium of laying hens. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0189329. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, X.; Cai, C.; Jia, R.; Bai, S.; Zeng, Q.; Mao, X.; Wang, J. Dietary resveratrol improved production performance, egg quality, and intestinal health of laying hens under oxidative stress. Poult. Sci. 2022, 101, 101886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, S.; He, W.; Qi, G.; Wang, J.; Qiu, K.; Ayalew, H.; Wu, S. Inclusion of guanidinoacetic acid in a low metabolizable energy diet improves broilers growth performance by elevating energy utilization efficiency through modulation serum metabolite profile. J. Anim. Sci. 2024, 102, skae001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, D.; Yang, L.; Li, J.; Dong, B.; Lai, W.; Zhang, L. Effects of guanidinoacetic acid on growth performance, creatine metabolism and plasma amino acid profile in broilers. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2019, 103, 766–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemme, A.; Ringel, J.; Rostagno, H.S.; Redshaw, M.S. Supplemental guanidino acetic acid improved feed conversion, weight gain, and breast meat yield in male and female broilers. In Proceedings of the 16th European Symposium on Poultry Nutrition, Strasbourg, France, 26–30 August 2007; pp. 335–338. [Google Scholar]

- Heger, J.; Zelenka, J.; Machander, V.; de la Cruz, C.; Lešták, M.; Hampel, D. Effects of guanidinoacetic acid supplementation to broiler diets with varying energy content. Acta Univ. Agric. Silvic. Mendel. Brun. 2014, 62, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraji, M.; Karimi Dehkordi, S.; Zamiani Moghadam, A.K.; Ahmadipour, B.; Khajali, F. Combined effects of guanidinoacetic acid, coenzyme Q10 and taurine on growth performance, gene expression and ascites mortality in broiler chickens. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2019, 103, 162–169. [Google Scholar]

- Boney, J.W.; Patterson, P.H.; Solis, F. The effect of dietary inclusions of guanidinoacetic acid on D1-42 broiler performance and processing yields. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2020, 29, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, C.; Eyng, C.; Viott, A.M.; De Avila, A.S.; Pacheco, W.J.; Junior, N.R.; Nunes, R.V. Effect of dietary guanidinoacetic acid or nucleotides supplementation on growth performances, carcass traits, meat quality and occurrence of myopathies in broilers. Livest. Sci. 2021, 251, 104659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, D.; El Sayed, R.; Abdelfattah-Hassan, A.; Morshedy, A.M. Creatine or guanidinoacetic acid? Which is more effective at enhancing growth, tissue creatine stores, quality of meat, and genes controlling growth/myogenesis in Mulard ducks. J. Appl. Anim. Res. 2019, 47, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabatabaei Yazdi, F.; Golian, A.; Zarghi, H.; Varidi, M. Effect of wheat-soy diet nutrient density and guanidine acetic acid supplementation on performance and energy metabolism in broiler chickens. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2017, 16, 593–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khajali, F.; Wideman, R.F. Dietary arginine: Metabolic, environmental, immunological and physiological interrelationships. World’s Poult. Sci. J. 2010, 66, 751–766. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Q.C.; Xuan, J.J.; Yan, X.C.; Hu, Z.Z.; Wang, F. Effects of dietary supplementation of guanidino acetic acid on growth performance, thigh meat quality and development of small intestine in Partridge-Shank broilers. J. Agric. Sci. 2018, 156, 1130–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Yan, Z.; Liu, S.; Yin, Y.; Yang, T.; Chen, Q. Regulative mechanism of guanidinoacetic acid on skeletal muscle development and its application prospects in animal husbandry: A review. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 714567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majdeddin, M.; Golian, A.; Kermanshahi, H.; De Smet, S.; Michiels, J. Guanidinoacetic acid supplementation in broiler chickens fed on corn-soybean diets affects performance in the finisher period and energy metabolites in breast muscle independent of diet nutrient density. Br. Poult. Sci. 2018, 59, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, J.L.; Wang, X.F.; Zhu, X.D.; Gao, F.; Zhou, G.H. Attenuating effects of guanidinoacetic acid on preslaughter transport-induced muscle energy expenditure and rapid glycolysis of broilers. Poult. Sci. 2019, 98, 3223–3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Faham, A.I.; Abdallah, A.G.; El-Sanhoury, M.H.S.; Ali, N.G.; Abddelaziz, M.A.M.; Abdelhady, A.Y.M.; Arafa, A.S.M. Effect of graded levels of guanidine acetic acid in low protein broiler diets on performance and carcass parameters. Egypt. J. Nutr. Feeds 2019, 22, 223–233. [Google Scholar]

- Maynard, C.J.; Nelson, D.S.; Rochell, S.J.; Owens, C.M. Reducing broiler breast myopathies through supplementation of guanidinoacetic acid in broiler diets. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2023, 32, 100324. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Liu, N.; He, Z.; Song, P.; Hao, M.; Xie, Y.; Sun, Z. Guanidino-acetic acid: A scarce substance in biomass that can regulate postmortem meat glycolysis of broilers subjected to pre-slaughter transportation. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 8, 631194. [Google Scholar]

| Tissues | Functions |

|---|---|

| Liver | Methylation of GAA to creatine (via guanidinoacetic acid methyltransferase) |

| Kidney/Pancreas | Synthesis of GAA (via Arg: Gly amidinotransferase) |

| Muscles/Brain | Uptake of creatine; energy buffering via phosphocreatine |

| 1. Formation of GAA | 2. Methylation of GAA to Creatine | 3. Transport and Storage |

|---|---|---|

| Location: Primarily occurs in the kidney and pancreas. | Location: Occurs mainly in the liver | Transport: Creatine is transported through the bloodstream to target tissues like skeletal muscle, heart and brain |

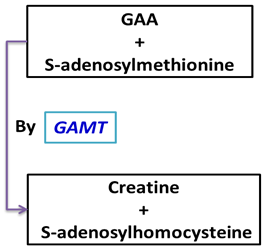

| Enzyme: L-arginine:glycine amidinotransferase (AGAT) | Enzyme: Guanidinoacetate N-methyltransferase (GAMT) | Storage: In these tissues, creatine is phosphorylated to phosphocreatine (PCr) by creatine kinase (CK) for use in energy buffering |

Reaction: | Reaction: |

| N | Actions | References |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sparing Arg for use in protein synthesis and muscle size augmentation | [2,20] |

| 2 | Arg is a precursor of growth-promoting polyamines (putrescine, spermidine, and spermine) Polyamines have anabolic functions in the body, such as synthesis of DNA, RNA, and proteins, as well as the cellular uptake of amino acids | [78] |

| 3 | Regulating the phosphocreatine/creatine kinase (PCr-CK) system by GAA. The PCr-CK system plays a vital role in cellular energy metabolism through ATP regeneration | [34] |

| 4 | Improving the efficiency of energy utilization by replenishing ATP through the Cre-PCre shuttle system in addition to its Arg-sparing effect, which plays a central role in endogenous nitric oxide synthesis and maximizing growth performance | [16] |

| 5 | Redirecting amino acids (arginine and glycine) toward functions such as protein synthesis | [9,21] |

| 6 | Elevating plasma insulin-like growth factor-I | [8] |

| 7 | Improving morphology of small intestine | [79] |

| GAA Dose | Species | Trial Duration | Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.6 and 1.2 g/kg | Broiler chicks | 1–42 days | Improving growth performance and FCR | [71] |

| 0.6 and 1.2 g/kg | Broiler chicks | 1–42 days | GAA can significantly enhance broiler chicken growth performance by affecting creatine metabolism and utilization efficiency of essential AA | [39] |

| 0.6 and 1.2 g/kg | Broiler chicks | 1–26 days | Improvement in feed conversion in the final period | [8] |

| 1.2 g/kg | Broiler chicks | 8–17 days | Significantly improved their weight gain and feed conversion | [9] |

| 0.6 g/kg | Broiler chicks | 0 to 40 days | Improved FCR and reduced feed intake, with no significant effects on BW gain. | [32] |

| 0.6, 1.2, 2.4 g/kg | Quail breeders | 25–29 weeks | Better weight gain and FCR in offspring | [57] |

| 0.6 g/kg | Broiler chicks | 1–35 days | Little effect on BW or BWG but improved FCR | [72] |

| 1.5 and 2 g/kg | Broiler chicks | 1–42 days | 1.5 g GAA improved FCR while having no effect on BWG or feed intake. Poor growth performance was caused by the high dose of GAA (2 g/kg) | [14] |

| 0.6 g/kg | Broiler chicks | 0–50 days | Improvement in FCR of 0.042 | [37] |

| 1.2 g/kg | Broiler chicks | 1–35 days | Heightened the compromised growth and enhanced the FCR of birds | [23] |

| 0.6 and 1.2 g/kg | Broiler chicks | 1–42 days | Enhancing BW, BWG, FCR and average daily feed intake | [42] |

| 0.75, 1.5 and 2.25 g/kg | Broiler chicks | 1–42 days | 1.5 g GAA improved BWG and FCR; higher supplementation (2.25 g/kg) worsened these responses. | [73] |

| 0.6 g/kg | Broiler chicks | 1–42 days | Improving BW and FCR | [74] |

| 0.6 g/kg | Broiler chicks | 1–32 days | Improving FCR by 4.03% | [30] |

| 0.6 g/kg | Broiler chicks | 1–42 days | Improved feed intake, BWG and growth performance | [75] |

| 0.6 g/kg | Broiler chicks | 1–43 days | Improving final BW and FCR | [53] |

| 0.6 and 6 g/kg | Broiler chicks | 1–35 days | Feeding 0.6 g/kg GAA did not improve growth performance, whereas 6.0 g/kg GAA resulted in a reduction of feed consumption and consequently of BWG | [22] |

| 0.6 and 1.2 g/kg | Broiler chicks | 28–42 days | No differences in ADG, ADFI, or feed efficiency | [82] |

| 0.6 and 1.2 g/kg | Qiandongnan Xiaoxiang chickens | 22–24 weeks | No effect on the ADFI, ADG | [85] |

| 1.2 g/kg | Broiler chicks | 1–42 days | No effect on feed intake, body weight gain, and FCR | [44] |

| 0.2, 0.4, 0.6 and 0.8 g/kg | Broiler chicks | 1–42 days | No effect on BW, BWG, or enhanced FCR | [69] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Elnesr, S.S.; Shehab-El-Deen, M. The Beneficial Effects of Guanidinoacetic Acid as a Functional Feed Additive: A Possible Approach for Poultry Production. Vet. Sci. 2026, 13, 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010046

Elnesr SS, Shehab-El-Deen M. The Beneficial Effects of Guanidinoacetic Acid as a Functional Feed Additive: A Possible Approach for Poultry Production. Veterinary Sciences. 2026; 13(1):46. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010046

Chicago/Turabian StyleElnesr, Shaaban S., and Mohamed Shehab-El-Deen. 2026. "The Beneficial Effects of Guanidinoacetic Acid as a Functional Feed Additive: A Possible Approach for Poultry Production" Veterinary Sciences 13, no. 1: 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010046

APA StyleElnesr, S. S., & Shehab-El-Deen, M. (2026). The Beneficial Effects of Guanidinoacetic Acid as a Functional Feed Additive: A Possible Approach for Poultry Production. Veterinary Sciences, 13(1), 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010046