Highly Conserved Influenza A Nucleoprotein as a Target for Broad-Spectrum Intervention: Characterization of a Monoclonal Antibody with Pan-Influenza Reactivity

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Lines, Viruses, and Animals

2.2. The Isolation of the Virus Strain

2.3. Genome Sequencing and Analysis

2.4. Mouse Immunization

2.5. Indirect Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (iELISA)

2.6. Subtype Identification

2.7. Western Blot

2.8. Indirect Immunofluorescence Assay (IFA)

2.9. Dot Blot

2.10. Truncation and Expression of NP Genes

2.11. Further Localization of the Amino Acid Sequence of the Linear B-Cell Epitope

2.12. H9N2-HN22 NP Protein Structure Prediction and Conservation Analysis of Antigenic Epitopes

2.13. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

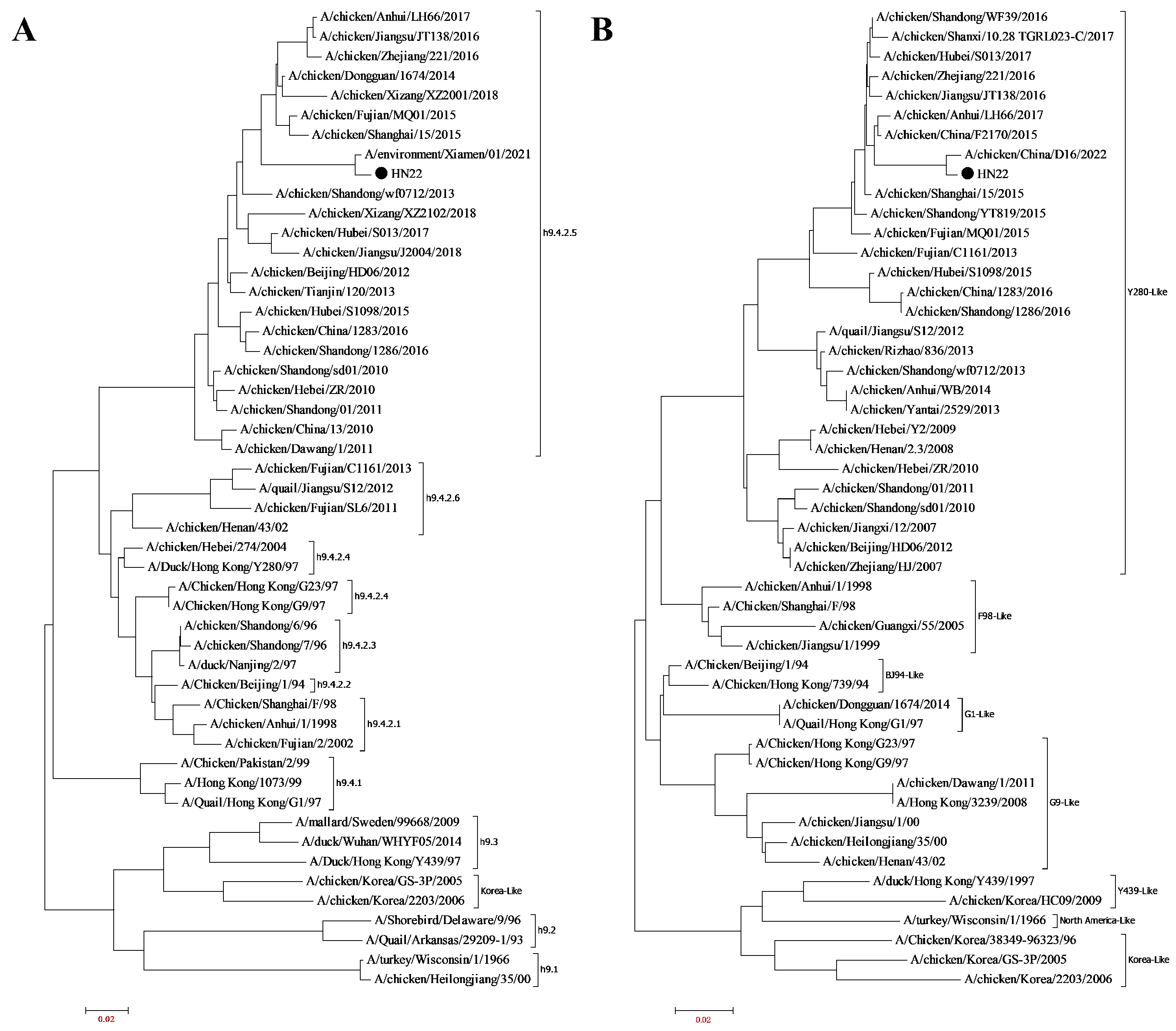

3.1. Virus Isolation and Identification

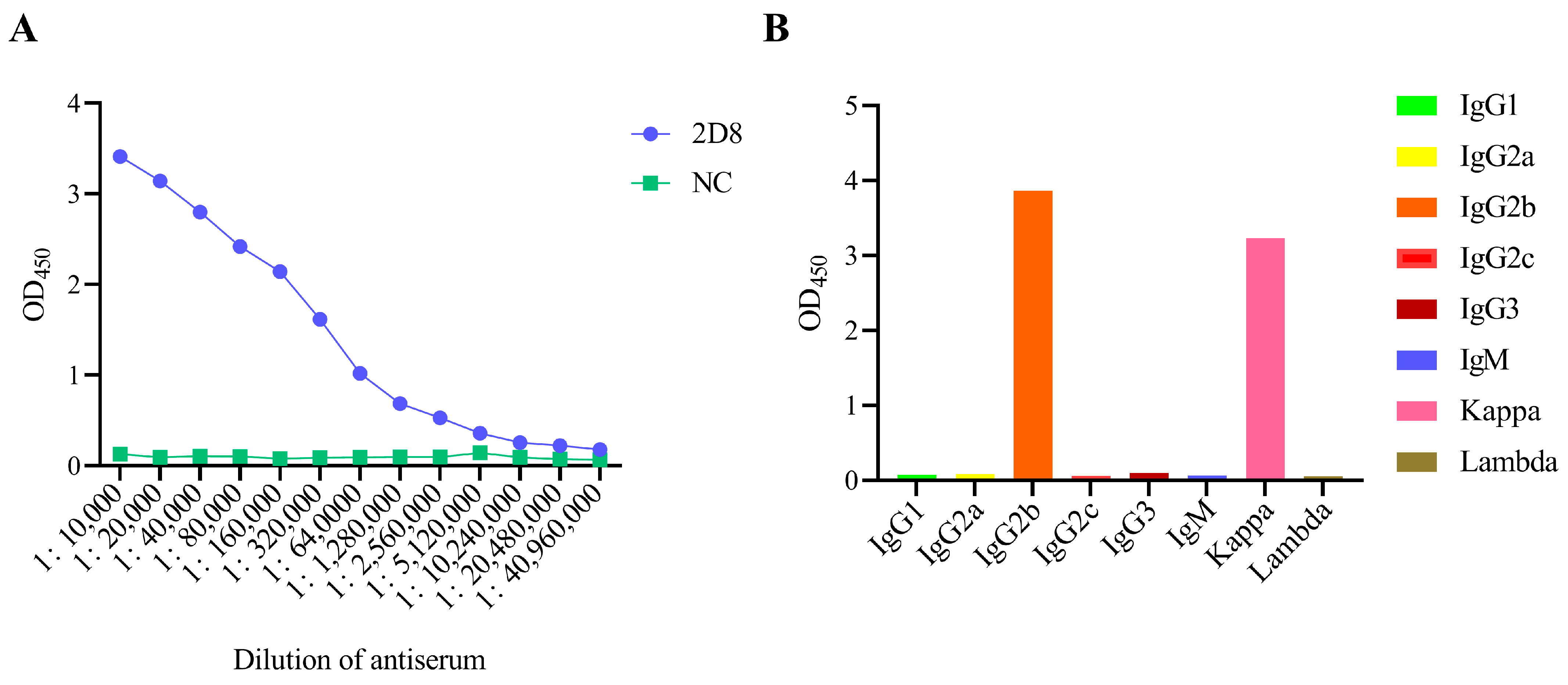

3.2. Generation of mAbs Against H9N2-HN22 Strain

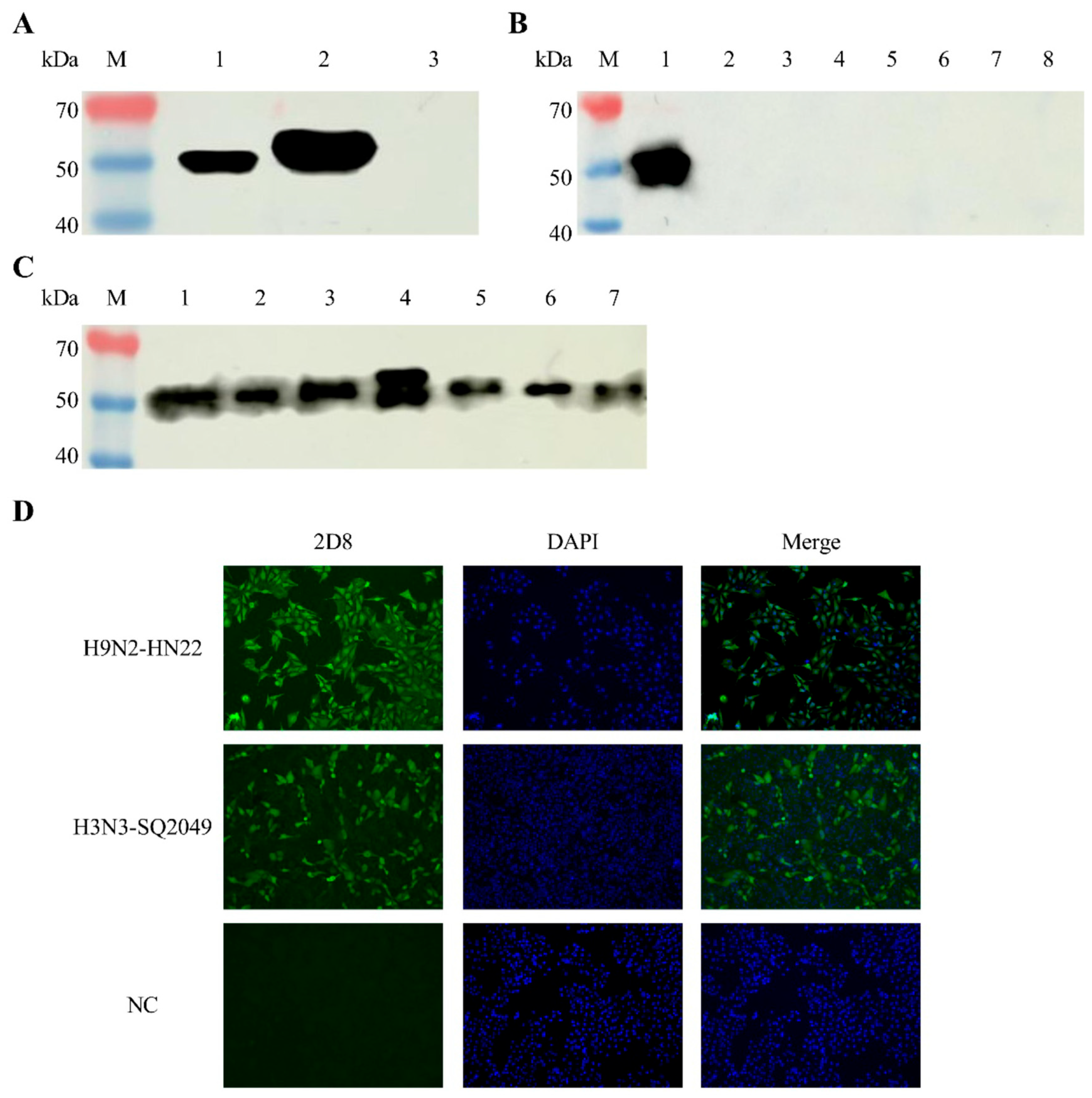

3.3. Identification of 2D8 mAb Characteristics

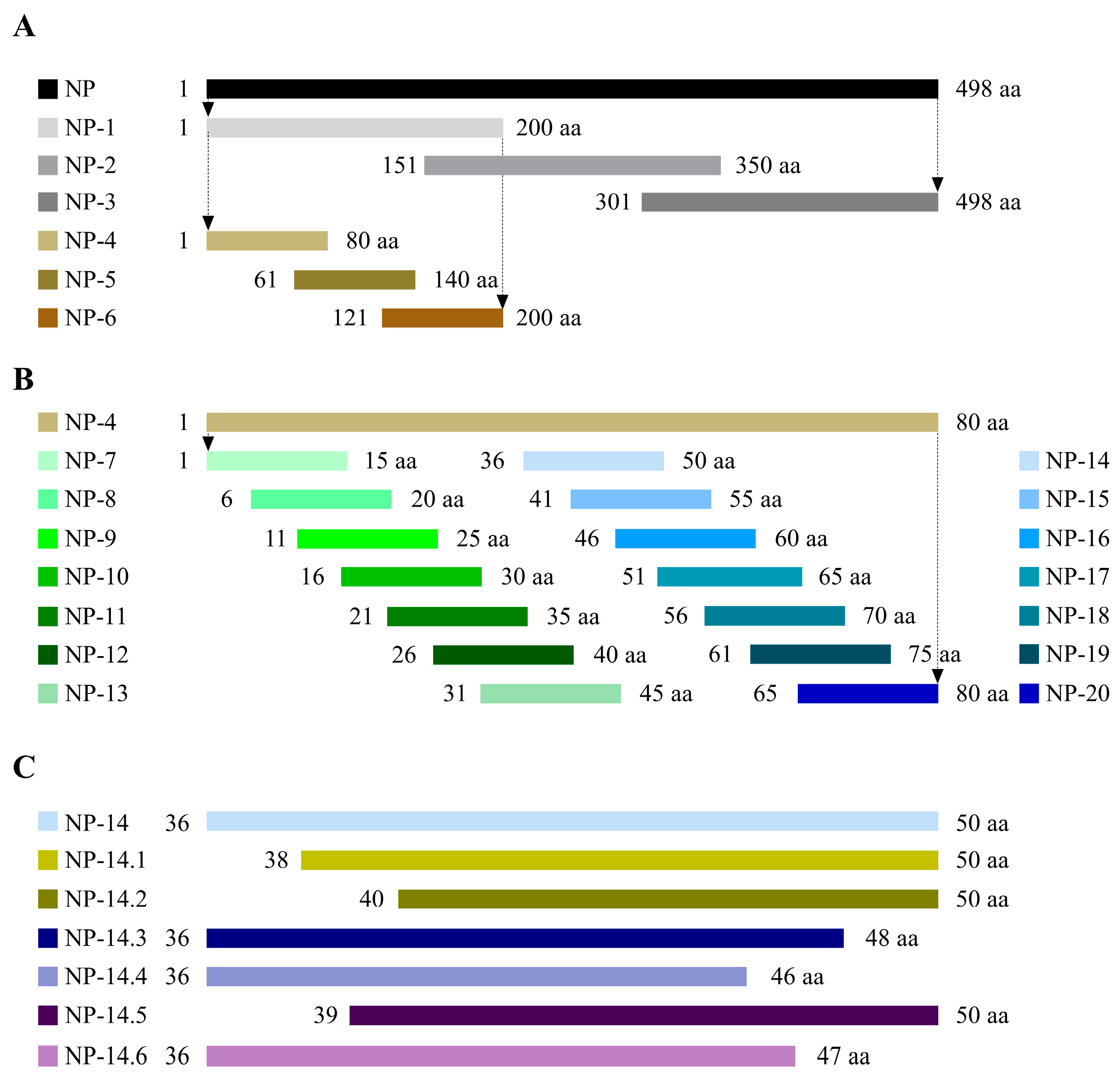

3.4. Peptide Truncation Strategies

3.5. Identification of Antigenic Epitopes in 2D8 mAb

3.6. Spatial Structure of Epitope

3.7. Conservative Analysis of Identified Epitope

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Paules, C.; Subbarao, K. Influenza. Lancet 2017, 390, 697–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Q.; Wang, S.; Liu, S.; Hou, G.; Li, J.; Jiang, W.; Wang, K.; Peng, C.; Liu, D.; Guo, A.; et al. Diversity and distribution of type A influenza viruses: An updated panorama analysis based on protein sequences. Virol. J. 2019, 16, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, S.; Reinhart, K.; Couture, A.; Kniss, K.; Davis, C.T.; Kirby, M.K.; Murray, E.L.; Zhu, S.; Kraushaar, V.; Wadford, D.A.; et al. Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Virus Infections in Humans. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 392, 843–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryt-Hansen, P.; George, S.; Hjulsager, C.K.; Trebbien, R.; Krog, J.S.; Ciucani, M.M.; Langerhuus, S.N.; DeBeauchamp, J.; Crumpton, J.C.; Hibler, T.; et al. Rapid surge of reassortant A(H1N1) influenza viruses in Danish swine and their zoonotic potential. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2025, 14, 2466686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Qin, K. Human-infecting influenza A (H9N2) virus: A forgotten potential pandemic strain? Zoonoses Public Health 2020, 67, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, M.; Zeng, X.; Xie, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, J.; Yang, J.; Yang, L.; Wang, D. Reported human infections of H9N2 avian influenza virus in China in 2021. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1255969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duong, M.H.; Phan, T.N.U.; Nguyen, T.H.; Ho, N.H.N.; Nguyen, T.N.; Nguyen, V.T.; Cao, M.T.; Luong, C.Q.; Nguyen, V.T.; Nguyen, V.T. Human Infection with Avian Influenza A(H9N2) Virus, Vietnam, April 2024. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2025, 31, 388–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potdar, V.; Hinge, D.; Satav, A.; Simões, E.A.F.; Yadav, P.D.; Chadha, M.S. Laboratory-Confirmed Avian Influenza A(H9N2) Virus Infection, India, 2019. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2019, 25, 2328–2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peiris, M.; Yuen, K.Y.; Leung, C.W.; Chan, K.H.; Ip, P.L.S.; Lai, R.W.M.; Orr, W.K.; Shortridge, K.F. Human infection with influenza H9N2. Lancet 1999, 354, 916–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Um, S.; Siegers, J.Y.; Sar, B.; Chin, S.; Patel, S.; Bunnary, S.; Hak, M.; Sor, S.; Sokhen, O.; Heng, S.; et al. Human Infection with Avian Influenza A(H9N2) Virus, Cambodia, February 2021. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2021, 27, 2742–2745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, P.P.; Zhang, Y.H.; Tian, K.Y.; Bian, C.Z.; Zhao, J. Development of a reverse transcription recombinase polymerase amplification combined with lateral-flow dipstick assay for avian influenza H9N2 HA gene detection. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2019, 66, 546–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, G.; Luo, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, C.; Duan, M.; Deliberto, T.J.; Nolte, D.L.; Ji, G.; He, H. Phylogenetic diversity and genotypical complexity of H9N2 influenza A viruses revealed by genomic sequence analysis. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e17212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peacock, T.H.P.; James, J.; Sealy, J.E.; Iqbal, M. A Global Perspective on H9N2 Avian Influenza Virus. Viruses 2019, 11, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrat, F.; Flahault, A. Influenza vaccine: The challenge of antigenic drift. Vaccine 2007, 25, 6852–6862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Zhang, N.; Yang, Y.; Liang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Suzuki, Y.; Wu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yang, H.; et al. Immune Escape Adaptive Mutations in Hemagglutinin Are Responsible for the Antigenic Drift of Eurasian Avian-Like H1N1 Swine Influenza Viruses. J. Virol. 2022, 96, e0097122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Shortridge, K.F.; Krauss, S.; Webster, R.G. Molecular characterization of H9N2 influenza viruses: Were they the donors of the “internal” genes of H5N1 viruses in Hong Kong? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 9363–9367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Li, H.; Tong, Q.; Han, Q.; Liu, J.; Yu, H.; Song, H.; Qi, J.; Li, J.; Yang, J.; et al. Airborne transmission of human-isolated avian H3N8 influenza virus between ferrets. Cell 2023, 186, 4074–4084.e4011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Shi, J.; Cui, P.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Hou, Y.; Liu, L.; Jiang, Y.; Guan, Y.; Chen, H.; et al. Genetic analysis and biological characterization of H10N3 influenza A viruses isolated in China from 2014 to 2021. J. Med. Virol. 2023, 95, e28476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Liu, B.Y.; Gong, L.; Chen, Z.; Chen, X.L.; Hou, S.; Yu, J.L.; Wu, J.B.; Xia, Z.C.; Latif, A.; et al. Genetic characterization of the first detected human case of avian influenza A (H5N6) in Anhui Province, East China. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 15282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Du, D.; Sun, Z.; Geng, X.; Liu, W.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Pang, W.; Tian, K. Evaluation of the immune effect of a triple vaccine composed of fowl adenovirus serotype 4 fiber-2 recombinant subunit, inactivated avian influenza (H9N2) vaccine, and Newcastle disease vaccine against respective pathogenic virus challenge in chickens. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2024, 33, 100410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Chen, H.; Meng, F.; Tao, S.; Ma, S.; Qiao, C.; Chen, H.; Yang, H. A single amino acid at position 158 in haemagglutinin affects the antigenic property of Eurasian avian-like H1N1 swine influenza viruses. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2022, 69, e236–e243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, S.; Pawan, K.; Mansor, M.D.; Farkad, B.; Jalal, N.A.; Hasan, M.A.; Amresh, P.; Kumar, V. In silico evaluation of the inhibitory potential of nucleocapsid inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2: A binding and energetic perspective. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2023, 41, 9797–9807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Sneyd, H.; Dekant, R.; Wang, J. Influenza A Virus Nucleoprotein: A Highly Conserved Multi-Functional Viral Protein as a Hot Antiviral Drug Target. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2017, 17, 2271–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, H.; Kukol, A. Harnessing viral internal proteins to combat flu and beyond. Virology 2025, 604, 110414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panthi, S.; Hong, J.-Y.; Satange, R.; Yu, C.-C.; Li, L.-Y.; Hou, M.-H. Antiviral drug development by targeting RNA binding site, oligomerization and nuclear export of influenza nucleoprotein. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 282, 136996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, C.-Y.; Tang, Y.-S.; Shaw, P.-C. Structure and Function of Influenza Virus Ribonucleoprotein. In Virus Protein and Nucleoprotein Complexes; Harris, J.R., Bhella, D., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 95–128. [Google Scholar]

- Miyoshi-Akiyama, T.; Yamashiro, T.; Mai, L.Q.; Narahara, K.; Miyamoto, A.; Shinagawa, S.; Mori, S.; Kitajima, H.; Kirikae, T. Discrimination of influenza A subtype by antibodies recognizing host-specific amino acids in the viral nucleoprotein. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses 2012, 6, 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myers, M.L.; Conlon, M.T.; Gallagher, J.R.; Woolfork, D.D.; Khorrami, N.D.; Park, W.B.; Stradtman-Carvalho, R.K.; Harris, A.K. Analysis of polyclonal and monoclonal antibody to the influenza virus nucleoprotein in different oligomeric states. Virus Res. 2025, 355, 199563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rak, A.; Isakova-Sivak, I.; Rudenko, L. Nucleoprotein as a Promising Antigen for Broadly Protective Influenza Vaccines. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayedahmed, E.E.; Elshafie, N.O.; dos Santos, A.P.; Jagannath, C.; Sambhara, S.; Mittal, S.K. Development of NP-Based Universal Vaccine for Influenza A Viruses. Vaccines 2024, 12, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrera-Rodriguez, J.; Meijerhof, T.; Niesters, H.G.; Stjernholm, G.; Hovden, A.-O.; Sørensen, B.; Ökvist, M.; Sommerfelt, M.A.; Huckriede, A. A novel peptide-based vaccine candidate with protective efficacy against influenza A in a mouse model. Virology 2018, 515, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuklina, M.; Stepanova, L.; Ozhereleva, O.; Kovaleva, A.; Vidyaeva, I.; Korotkov, A.; Tsybalova, L. Inserting CTL Epitopes of the Viral Nucleoprotein to Improve Immunogenicity and Protective Efficacy of Recombinant Protein against Influenza A Virus. Biology 2024, 13, 801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eickhoff, C.S.; Terry, F.E.; Peng, L.; Meza, K.A.; Sakala, I.G.; Van Aartsen, D.; Moise, L.; Martin, W.D.; Schriewer, J.; Buller, R.M.; et al. Highly conserved influenza T cell epitopes induce broadly protective immunity. Vaccine 2019, 37, 5371–5381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, E.; Stech, J.; Guan, Y.; Webster, R.G.; Perez, D.R. Universal primer set for the full-length amplification of all influenza A viruses. Arch. Virol. 2001, 146, 2275–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Momont, C.; Dang, H.V.; Zatta, F.; Hauser, K.; Wang, C.; di Iulio, J.; Minola, A.; Czudnochowski, N.; De Marco, A.; Branch, K.; et al. A pan-influenza antibody inhibiting neuraminidase via receptor mimicry. Nature 2023, 618, 590–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray, R.; Nait Mohamed, F.A.; Maurer, D.P.; Huang, J.; Alpay, B.A.; Ronsard, L.; Xie, Z.; Han, J.; Fernandez-Quintero, M.; Phan, Q.A.; et al. Eliciting a single amino acid change by vaccination generates antibody protection against group 1 and group 2 influenza A viruses. Immunity 2024, 57, 1141–1159.e1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Chen, J.; Zhang, J.; Tan, L.; Lu, G.; Luo, Y.; Pan, T.; Liang, J.; Li, Q.; Luo, B.; et al. Identification of a novel compound targeting the nuclear export of influenza A virus nucleoprotein. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2018, 22, 1826–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, Y.; Li, B.; Zhou, L.; Luo, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, S.; Lu, Q.; Tan, W.; Chen, Z. Protein transduction domain-mediated influenza NP subunit vaccine generates a potent immune response and protection against influenza virus in mice. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020, 9, 1933–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Xu, J.; Chen, Z.; Wei, Y.; Wang, Q.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, Q.; Xu, S. Broad-spectrum inhibition of influenza A virus replication by blocking the nuclear export of viral ribonucleoprotein complexes. J. Virol. 2025, 99, e0147825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashour, J.; Schmidt Florian, I.; Hanke, L.; Cragnolini, J.; Cavallari, M.; Altenburg, A.; Brewer, R.; Ingram, J.; Shoemaker, C.; Ploegh Hidde, L. Intracellular Expression of Camelid Single-Domain Antibodies Specific for Influenza Virus Nucleoprotein Uncovers Distinct Features of Its Nuclear Localization. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 2792–2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, M.; Jiao, J.; Liu, S.; Zhao, W.; Ge, Z.; Cai, K.; Xu, L.; He, D.; Zhang, X.; Qi, X.; et al. Monoclonal antibody targeting a novel linear epitope on nucleoprotein confers pan-reactivity to influenza A virus. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 107, 2437–2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuong, N.H.; Kwak, C.; Heo, C.-Y.; Cho, E.W.; Yang, J.; Poo, H. Development and Characterization of Monoclonal Antibodies against Nucleoprotein for Diagnosis of Influenza A Virus. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 28, 809–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyoshi-Akiyama, T.; Narahara, K.; Mori, S.; Kitajima, H.; Kase, T.; Morikawa, S.; Kirikae, T. Development of an immunochromatographic assay specifically detecting pandemic H1N1 (2009) influenza virus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2010, 48, 703–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Luo, J.; Chen, Z. Development of universal influenza vaccines based on influenza virus M and NP genes. Infection 2014, 42, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Kang, J.O.; Chang, J. Nucleoprotein vaccine induces cross-protective cytotoxic T lymphocytes against both lineages of influenza B virus. Clin. Exp. Vaccine Res. 2019, 8, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Campo, J.; Bouley, J.; Chevandier, M.; Rousset, C.; Haller, M.; Indalecio, A.; Guyon-Gellin, D.; Le Vert, A.; Hill, F.; Djebali, S.; et al. OVX836 Heptameric Nucleoprotein Vaccine Generates Lung Tissue-Resident Memory CD8+ T-Cells for Cross-Protection Against Influenza. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 678483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensen, L.; Illing, P.T.; Bridie Clemens, E.; Nguyen, T.H.O.; Koutsakos, M.; van de Sandt, C.E.; Mifsud, N.A.; Nguyen, A.T.; Szeto, C.; Chua, B.Y.; et al. CD8(+) T cell landscape in Indigenous and non-Indigenous people restricted by influenza mortality-associated HLA-A*24:02 allomorph. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, J.; Bilsel, P.; del Guercio, M.F.; Marinkovic-Petrovic, A.; Southwood, S.; Stewart, S.; Ishioka, G.; Kotturi, M.F.; Botten, J.; Sidney, J.; et al. Identification of broad binding class I HLA supertype epitopes to provide universal coverage of influenza A virus. Hum. Immunol. 2010, 71, 468–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanker, D.J.; Oveissi, S.; Tscharke, D.C.; Duan, M.; Wan, S.; Zhang, X.; Xiao, K.; Mifsud, N.A.; Gibbs, J.; Izzard, L.; et al. Influenza A Virus Infection Induces Viral and Cellular Defective Ribosomal Products Encoded by Alternative Reading Frames. J. Immunol. 2019, 202, 3370–3380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zheng, H.; Guo, P.; Hu, L.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J.; Ju, Y.; Meng, S. Broadly Protective CD8(+) T Cell Immunity to Highly Conserved Epitopes Elicited by Heat Shock Protein gp96-Adjuvanted Influenza Monovalent Split Vaccine. J. Virol. 2021, 95, e00507-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, P.G.; Keating, R.; Hulse-Post, D.J.; Doherty, P.C. Cell-mediated protection in influenza infection. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2006, 12, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene | Primers | Primer Sequences (5′–3′) | Region | Gene Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NP | NP-F | CGCGGATCCATGGCGTCTCAAGGCACCAAACGAT | 1–498 aa | 1–1494 bp |

| NP-R | CCCAAGCTTTTAATTGTCATATTCCTCTGCATTG | |||

| NP-1 | NP-1-F | CGCGGATCCATGGCGTCTCAAGGCACCAAACGAT | 1–200 aa | 1–600 bp |

| NP-1-R | CCCAAGCTTTTAACCTCGTTTTATCATTCGAATC | |||

| NP-2 | NP-2-F | CGCGGATCCACGAGAGCTCTTGTACGTACTGGAA | 151–350 aa | 451–1050 bp |

| NP-2-R | CCCAAGCTTTTATGTCCCTCTGATGAAACTTGAG | |||

| NP-3 | NP-3-F | CGCGGATCCATAGACCCTTTCCGTCTGCTTCAAA | 301–498 aa | 901–1494 bp |

| NP-3-R | CCCAAGCTTTTAATTGTCATATTCCTCTGCATTG | |||

| NP-4 | NP-4-F | CGCGGATCCATGGCGTCTCAAGGCACCAAACGAT | 1–80 aa | 1–240 bp |

| NP-4-R | CCCAAGCTTTTATTCCAGATATCTGTTCCTTCTT | |||

| NP-5 | NP-5-F | CGCGGATCCATAACAATAGAGAGAATGGTACTCT | 61–140 aa | 181–420 bp |

| NP-5-R | CCCAAGCTTTTAGTGCCATATCATCATATGGGTA | |||

| NP-6 | NP-6-F | CGCGGATCCCGTCAAGCGAACAATGGAGAAGACG | 121–200 aa | 361–600 bp |

| NP-6-R | CCCAAGCTTTTAACCTCGTTTTATCATTCGAATC |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, J.; Gao, W.; Zhao, K.; Huang, Z.; Liu, L.; Chang, J.; Cao, X.; Zhou, W.; Zhou, X.; Liu, Y.; et al. Highly Conserved Influenza A Nucleoprotein as a Target for Broad-Spectrum Intervention: Characterization of a Monoclonal Antibody with Pan-Influenza Reactivity. Vet. Sci. 2026, 13, 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010045

Liu J, Gao W, Zhao K, Huang Z, Liu L, Chang J, Cao X, Zhou W, Zhou X, Liu Y, et al. Highly Conserved Influenza A Nucleoprotein as a Target for Broad-Spectrum Intervention: Characterization of a Monoclonal Antibody with Pan-Influenza Reactivity. Veterinary Sciences. 2026; 13(1):45. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010045

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Jingrui, Wenming Gao, Kunkun Zhao, Zongmei Huang, Lin Liu, Jingjing Chang, Xiaoyang Cao, Wenwen Zhou, Xiaojie Zhou, Yuman Liu, and et al. 2026. "Highly Conserved Influenza A Nucleoprotein as a Target for Broad-Spectrum Intervention: Characterization of a Monoclonal Antibody with Pan-Influenza Reactivity" Veterinary Sciences 13, no. 1: 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010045

APA StyleLiu, J., Gao, W., Zhao, K., Huang, Z., Liu, L., Chang, J., Cao, X., Zhou, W., Zhou, X., Liu, Y., Li, X., & Song, Y. (2026). Highly Conserved Influenza A Nucleoprotein as a Target for Broad-Spectrum Intervention: Characterization of a Monoclonal Antibody with Pan-Influenza Reactivity. Veterinary Sciences, 13(1), 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010045