Molecular Identification, Occurrence, and Risk Factors for Small Babesia Species Among American Stafford Terriers in Serbia

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection and Study Population

2.2. Extraction and PCR Detection

2.3. Sanger Sequencing

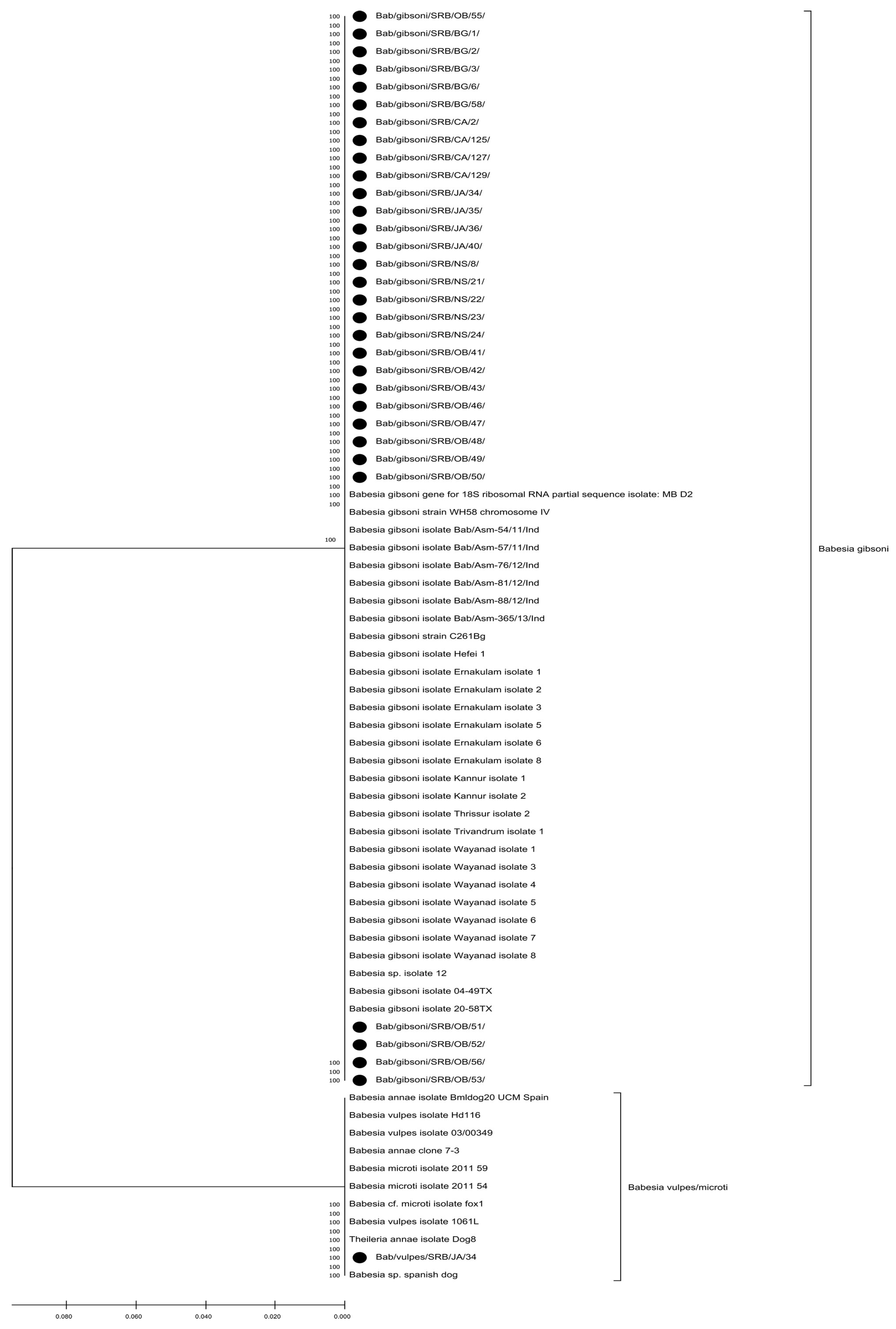

2.4. Phylogenetic Analysis

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Prevalence and Risk Factors for Small Babesia Species Infection

3.2. Sequencing Results

3.3. Phylogenetic Analysis Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Prevalence of Babesia gibsoni and B. vulpes in ASTs in Serbia

4.2. Small Babesia Species Infected ASTs with and Without Clinical Signs

4.3. Transmission Routes of Small Babesia Species: Dog Bites vs. Tick Exposure

4.4. Possible Vertical Transmission of Small Babesia Species and Other Risk Factors

4.5. Genealogy of Small Babesia Species

4.6. Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Janjić, F.; Sarvan, D.; Tomanović, S.; Ćuk, J.; Krstić, V.; Radonjić, V.; Ajtić, J. A short-term and long-term relationship between occurrence of acute canine babesiosis and meteorological parameters in Belgrade, Serbia. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis. 2019, 10, 101273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krstic, V.; Trailović, D.; Andrić, N.; Čalić, M.; Jovanović, M. Contribution to epizootiology of dog babesiosis in Belgrade area. In Proceedings of the 7th Conference Veterinarians of Serbia, Zlatibor, Yugoslavia, 13–16 September 1994; pp. 25–26. [Google Scholar]

- Davitkov, D.; Vucicevic, M.; Stevanovic, J.; Krstic, V.; Tomanovic, S.; Glavinic, U.; Stanimirovic, Z. Clinical babesiosis and molecular identification of Babesia canis and Babesia gibsoni infections in dogs from Serbia. Acta Vet. Hung. 2015, 63, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milošević, S.; Ilić Božović, A.; Magaš, V.; Sukara, R.; Tomanović, S.; Radaković, M.; Spariosu, K.; Kovačević Filipović, M.; Francuski Andrić, J. First clinical evidence with one-year monitoring of Babesia gibsoni mono-infection in two dogs from Serbia. Pak. Vet. J. 2024, 4, 1315–1321. [Google Scholar]

- Spariosu, K.; Davitkov, D.; Glišić, D.; Janjić, F.; Stepanović, P.; Kovačević Filipović, M. The first clinical case of Babesia vogeli infection in a dog from Serbia. Acta Vet.-Beograd 2025, 75, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovačević Filipović, M.M.; Beletić, A.D.; Božović, A.V.I.; Milanović, Z.; Tyrrell, P.; Buch, J.; Breitschwerdt, E.B.; Birkenheuer, A.J.; Chandrashekar, R. Molecular and serological prevalence of Anaplasma, Ehrlichia, Borrelia and Babesia spp. among clinically healthy outdoor dogs in Serbia. Vet. Parasitol. Reg. Stud. Rep. 2018, 14, 117–122. [Google Scholar]

- Camacho, A.T.; Pallas, E.; Gestal, J.J.; Guitián, F.J.; Olmeda, A.S.; Goethert, H.K.; Telford, S.R. Infection of dogs in northwest Spain with a Babesia microti-like agent. Vet. Rec. 2001, 149, 552–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrielli, S.; Otašević, S.; Ignjatović, A.; Savić, S.; Fraulo, M.; Arsić-Arsenijević, V.; Momčilović, S.; Cancrini, G. Canine Babesioses in noninvestigated areas of Serbia. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2015, 15, 535–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukara, R.; Chochlakis, D.; Ćirović, D.; Penezić, A.; Mihaljica, D.; Ćakić, S.; Valčić, M.; Tselentis, Y.; Psaroulaki, A.; Tomanović, S. Golden jackals (Canis aureus) as hosts for ticks and tick-borne pathogens in Serbia. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis. 2018, 9, 1090–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birkenheuer, A.J.; Buch, J.; Beall, M.J.; Braff, J.; Chandrashekar, R. Global distribution of canine Babesia species identified by a commercial diagnostic laboratory. Vet. Parasitol. Reg. Stud. Rep. 2020, 22, 100471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.P.; Xie, G.C.; Li, D.; Su, M.; Jian, R.; Du, L.Y. Molecular detection and genetic characteristics of Babesia gibsoni in dogs in Shaanxi Province, China. Parasites Vectors 2020, 13, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neelawala, D.; Dissanayake, D.R.A.; Prasada, D.V.P.; Silva, I.D. Analysis of risk factors associated with recurrence of canine babesiosis caused by Babesia gibsoni. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2021, 74, 101572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuu, A.; Kawabe, A.; Koshida, Y.; Ikadai, H.; Okano, S.; Higuchi, S. Incidence of canine Babesia gibsoni infection and subclinical infection among Tosa dogs in Aomori Prefecture, Japan. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2004, 66, 893–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, S.K.; Levy, J.K.; Crawford, P.C. Efficacy of azithromycin and compounded atovaquone for treatment of Babesia gibsoni in dogs. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2017, 31, 1108–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birkenheuer, A.J.; Marr, H.S.; Wilson, J.M.; Breitschwerdt, E.B.; Qurollo, B.A. Babesia gibsoni cytochrome b mutations in canine blood samples submitted to a US veterinary diagnostic laboratory. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2018, 32, 1965–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jongejan, F.; Su, B.L.; Yang, H.J.; Berger, L.; Bevers, J.; Liu, P.C.; Fang, J.C.; Cheng, Y.W.; Kraakman, C.; Plaxton, N. Molecular evidence for the transovarial passage of Babesia gibsoni in Haemaphysalis hystricis ticks from Taiwan: A novel vector for canine babesiosis. Parasites Vectors 2018, 11, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solano-Gallego, L.; Sainz, A.; Roura, X.; Estrada-Peña, A.; Miró, G. A review of canine babesiosis: The European perspective. Parasites Vectors 2016, 9, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkenheuer, A.J.; Correa, M.T.; Levy, M.G.; Breitschwerdt, E.B. Geographic distribution of babesiosis among dogs in the United States and association with dog bites: 150 cases (2000–2003). J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2005, 227, 942–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, A.T.; Pallas, E.; Gestal, J.J.; Guitián, F.J.; Olmeda, A.S.; Telford, S.R.; Spielman, A. Ixodes hexagonus is the main candidate as vector of Theileria annae in northwest Spain. Vet. Parasitol. 2003, 112, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomanović, S.; Radulović, Ž.; Ćakić, S.; Mihaljica, D.; Sukara, R.; Penezić, A.; Burazerović, J.; Ćirović, D. Tick species (Acari: Ixodidae) of red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) in Serbia. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Symposium on Hunting, Novi Sad, Serbia, 17–20 October 2013; pp. 107–108. [Google Scholar]

- Ushigusa, T.; Mizuishi, Y.; Katuyama, Y.; Sunaga, F.; Namikawa, K.; Kanno, Y. A Case of Babesia gibsoni Possibly Developed by Transplacental Infection. J. Anim. Protozooses Jpn. 2005, 20, 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Stegeman, J.R.; Birkenheuer, A.J.; Kruger, J.M.; Breitschwerdt, E.B. Transfusion-associated Babesia gibsoni infection in a dog. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2003, 222, 959–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Singh, H.; Singh, N.K.; Singh, N.D.; Rath, S.S. Canine babesiosis in Northwestern India: Molecular detection and assessment of risk factors. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 741785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muguiro, D.H.; Nekouei, O.; Lee, K.Y.; Hill, F.; Barrs, V.R. Prevalence of Babesia and Ehrlichia in owned dogs with suspected tick-borne infection in Hong Kong, and risk factors associated with Babesia gibsoni. Prev. Vet. Med. 2023, 214, 105908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, I.; Helm, C.S.; von Samson-Himmelstjerna, G.; Krücken, J.; Kottmann, T.; Holtdirk, A.; Kohn, B.; Hendrick, G.; Marsboom, C.; Müller, E. Molecular detection of Babesia spp. in dogs in Germany (2007–2020) and identification of potential risk factors for infection. Parasites Vectors 2023, 16, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janjić, F.; Živanović, D.; Radaković, M.; Davitkov, D.; Spariosu, K.; Francuski Andrić, J.; Kovačević Filipović, M. Trends in the top ten popular dog breeds in Serbia (2008–2022). Vet. Glas. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmeda, A.S.; Armstrong, P.M.; Rosenthal, B.M.; Valladares, B.; Del Castillo, A.; De Armas, F.; Miguelez, G.; González, A.; Rodrı;guez Rodrıguez, J.A.; Spielman, A.; et al. A subtropical case of human babesiosis. Acta Trop. 1997, 67, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuska-Szalay, B.; Vizi, Z.; Hofmann-Lehmann, R.; Vajdovich, P.; Takács, N.; Meli, M.L.; Farkas, R.; Stummer-Knyihár, V.; Jerzsele, Á.; Kontschán, J.; et al. Babesia gibsoni emerging with high prevalence and co-infections in “fighting dogs” in Hungary. Curr. Res. Parasitol. Vector Borne Dis. 2021, 1, 100048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannon, S.H.; Levy, J.K.; Kirk, S.K.; Crawford, P.C.; Leutenegger, C.M.; Shuster, J.J.; Chandrashekar, R. Infectious di eases in dogs rescued during dogfighting investigations. Vet. J. 2016, 211, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miró, G.; Checa, R.; Paparini, A.; Ortega, N.; González-Fraga, J.L.; Gofton, A.; Bartolomé, A.; Montoya, A.; Gálvez, R.; Mayo, P.P.; et al. Theileria annae (syn. Babesia microti-like) infection in dogs in NW Spain detected using direct and indirect diagnostic techniques: Clinical report of 75 cases. Parasites Vectors 2015, 8, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garden, O.A.; Kidd, L.; Mexas, A.M.; Chang, Y.M.; Jeffery, U.; Blois, S.L.; Fogle, J.E.; MacNeill, A.L.; Lubas, G.; Birkenheuer, A.; et al. ACVIM consensus statement on the diagnosis of immune-mediated hemolytic anemia in dogs and cats. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2019, 33, 313–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macintire, D.K.; Boudreaux, M.K.; West, G.D.; Bourne, C.; Wright, J.C.; Conrad, P.A. Babesia gibsoni infection among dogs in the southeastern United States. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2002, 220, 325–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, A.L.; Shiel, R.E.; Irwin, P.J. Clinical, haematological, cytokine and acute phase protein changes during experimental Babesia gibsoni infection of beagle puppies. Exp. Parasitol. 2015, 157, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, R.; Vojta, L.; Mrljak, V.; Marinculić, A.; Beck, A.; Zivicnjak, T.; Cacciò, S.M. Diversity of Babesia and Theileria species in symptomatic and asymptomatic dogs in Croatia. Int. J. Parasitol. 2009, 39, 843–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solano-Gallego, L.; Baneth, G. Babesiosis in dogs and cats—Expanding parasitological and clinical spectra. Vet. Parasitol. 2011, 181, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Notari, L.; Cannas, S.; Di Sotto, Y.A.; Palestrini, C. A retrospective analysis of dog–dog and dog–human cases of aggression in Northern Italy. Animals 2020, 10, 1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milanović, Z.; Beletić, A.; Vekić, J.; Zeljković, A.; Andrić, N.; Božović, A.I.; Filipović, M.K. Evidence of acute phase reaction in asymptomatic dogs naturally infected with Babesia canis. Vet. Parasitol. 2020, 282, 109140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milošević, S.; Francuski Andrić, J.; Vakanjac, S.; Nedić, S.; Kovačević Filipović, M.; Diklić, M.; Glišić, D.; Magaš, V. Male fertility impairment associated with Babesia gibsoni infection in dogs. Pak. Vet. J. 2025, 45, 262. [Google Scholar]

- Birkenheuer, A.J.; Levy, M.G.; Breitschwerdt, E.B. Efficacy of combined atovaquone and azithromycin for therapy of chronic Babesia gibsoni (Asian genotype) infections in dogs. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2004, 18, 494–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almendros, A.; Burchell, R.; Wierenga, J. An alternative combination therapy with metronidazole, clindamycin and doxycycline for Babesia gibsoni (Asian genotype) in dogs in Hong Kong. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2020, 82, 1334–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baneth, G.; Cardoso, L.; Brilhante-Simões, P.; Schnittger, L. Establishment of Babesia vulpes n. sp. (Apicomplexa: Babesiidae), a piroplasmid species pathogenic for domestic dogs. Parasites Vectors 2019, 12, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jefferies, R.; Ryan, U.M.; Jardine, J.; Robertson, I.D.; Irwin, P.J. Babesia gibsoni: Detection during experimental infections and after combined atovaquone and azithromycin therapy. Exp. Parasitol. 2007, 117, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goethert, H.K. What Babesia microti is now. Pathogens 2021, 10, 1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Negative n = 64 | Positive n = 37 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| With/without clinical signs | 0.7 | 3.1 | Fisher’s Exact p = 0.003 |

| With clinical signs | 28 (43.8%) | 28 (75.6%) | |

| B. gibsoni | / | 27 (72.9%) | |

| B. vulpes | / | 1 (2.7%) | |

| Without clinical signs | 36 (56.2%) | 9 (24.4%) | |

| B. gibsoni | / | 9 (24.4%) | |

| B. vulpes | / | 0 |

| PCR-Negative n = 64 | PCR-Positive n = 37 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| With clinical signs | |||

| Body temperature (°C) | 39 (37–41)28 | 38 (37–40)28 | p = 0.058 |

| Weight (kg) | 18 (10–33)28 | 20 (15–28)28 | p = 0.097 |

| Age (years) | 4 (2–9)28 | 4 (2–9)28 | p = 0.555 |

| Without clinical signs | |||

| Body temperature (°C) | 38 (37–38)36 | 38 (37–38)9 | p = 0.686 |

| Weight (kg) | 21.5 (15–41)36 | 18 (15–30)9 | p = 0.267 |

| Age (years) | 4 (2–9)36 | 3 (2–8)9 | p = 0.393 |

| PCR-Negative n = 64 | PCR-Positive n = 37 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | p = 0.216 | ||

| Male | 45.3% | 59.5% | |

| Female | 54.7% | 40.5% | |

| Fatigue | p = 0.059 | ||

| Yes | 1.6% | 10.8% | |

| No | 98.4% | 88.2% | |

| Recent wounds | p = 0.766 | ||

| Yes | 12.5% | 16.2% | |

| No | 87.5% | 83.8% | |

| Scars | p = 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 60.9% | 91.9% | |

| No | 39.1% | 8.1% | |

| BCS | p < 0.001 | ||

| 1 | 1.6% | 13.5% | |

| 2 | 9.5% | 35.1% | |

| 3 | 31.7% | 21.6% | |

| 4 | 36.5% | 21.6% | |

| 5 | 20.6% | 8.1% | |

| History of VBD | p = 0.035 | ||

| Yes | 4.7% | 18.9% | |

| No | 95.3% | 81.1% |

| PCR-Negative n = 64 | PCR-Positive n = 37 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Households | p = 0.531 | ||

| Single-dog | 3.1% | 0.0% | |

| Multi-dog | 96.9% | 100.0% | |

| Housing | p = 0.205 | ||

| Indoor | 29.7% | 16.2% | |

| Outdoor | 70.3% | 83.8% | |

| Antiparasitics | p = 0.105 | ||

| Yes | 62.5% | 67.6% | |

| No | 37.4% | 32.4% | |

| Ticks’ exposure | p = 0.004 | ||

| Yes | 3.1% | 21.6% | |

| No | 96.9% | 78.4% | |

| District | p < 0.001 | ||

| Urban | 76.5% | 23.5% | |

| Rural | 36.4% | 63.6% |

| Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Intervals | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rural environment | 5.68 | 2.30–14.08 | <0.001 |

| Presence of scars | 4.00 | 1.74–9.19 | 0.001 |

| Ticks exposure | 3.53 | 0.90–13.86 | 0.071 |

| Previous vector-borne disease | 2.99 | 0.88–10.18 | 0.080 |

| Low body condition score | 2.91 | 1.18–7.19 | 0.021 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Davitkov, D.; Kovačević Filipović, M.; Glišić, D.; Tarić, E.; Ilić Bozović, A.; Radaković, M.; Davitkov, D. Molecular Identification, Occurrence, and Risk Factors for Small Babesia Species Among American Stafford Terriers in Serbia. Vet. Sci. 2026, 13, 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010026

Davitkov D, Kovačević Filipović M, Glišić D, Tarić E, Ilić Bozović A, Radaković M, Davitkov D. Molecular Identification, Occurrence, and Risk Factors for Small Babesia Species Among American Stafford Terriers in Serbia. Veterinary Sciences. 2026; 13(1):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010026

Chicago/Turabian StyleDavitkov, Dajana, Milica Kovačević Filipović, Dimitrije Glišić, Elmin Tarić, Anja Ilić Bozović, Milena Radaković, and Darko Davitkov. 2026. "Molecular Identification, Occurrence, and Risk Factors for Small Babesia Species Among American Stafford Terriers in Serbia" Veterinary Sciences 13, no. 1: 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010026

APA StyleDavitkov, D., Kovačević Filipović, M., Glišić, D., Tarić, E., Ilić Bozović, A., Radaković, M., & Davitkov, D. (2026). Molecular Identification, Occurrence, and Risk Factors for Small Babesia Species Among American Stafford Terriers in Serbia. Veterinary Sciences, 13(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010026