Transcriptome-Wide Identification and Analysis Reveals m6A Regulation of Porcine Intestinal Epithelial Cells Under TGEV Infection

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture and TGEV Infection

2.2. TCID50 Assay

2.3. m6A MeRIP-Seq and RNA-Seq

2.4. Sequencing Data Analysis

2.5. qPCR Analysis

2.6. Western Blotting Analysis

2.7. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Establishment of TGEV-Infected IPEC-J2 Cell Model

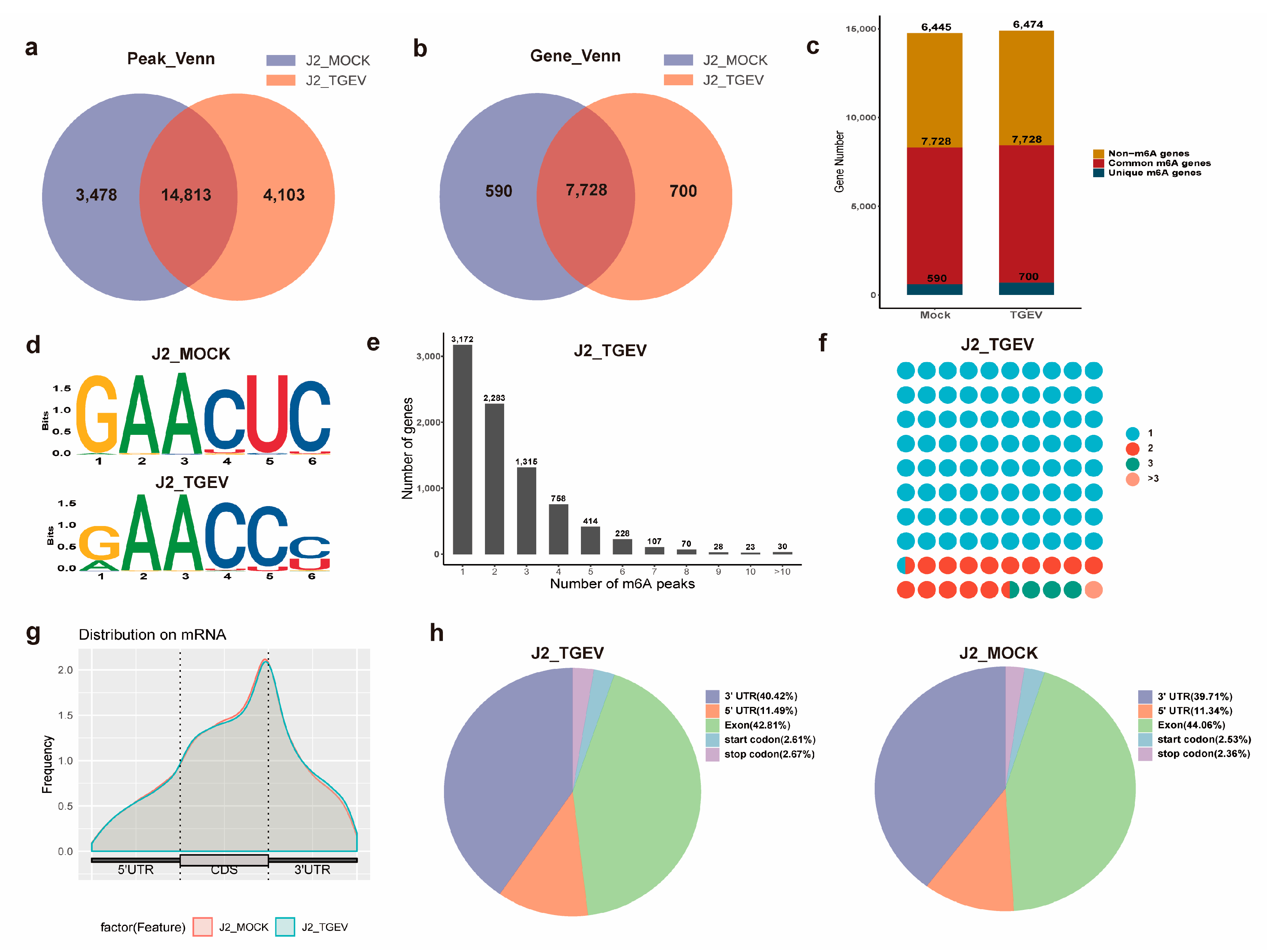

3.2. Transcriptome-Wide Characterization of m6A Modification Dynamics upon TGEV Infection

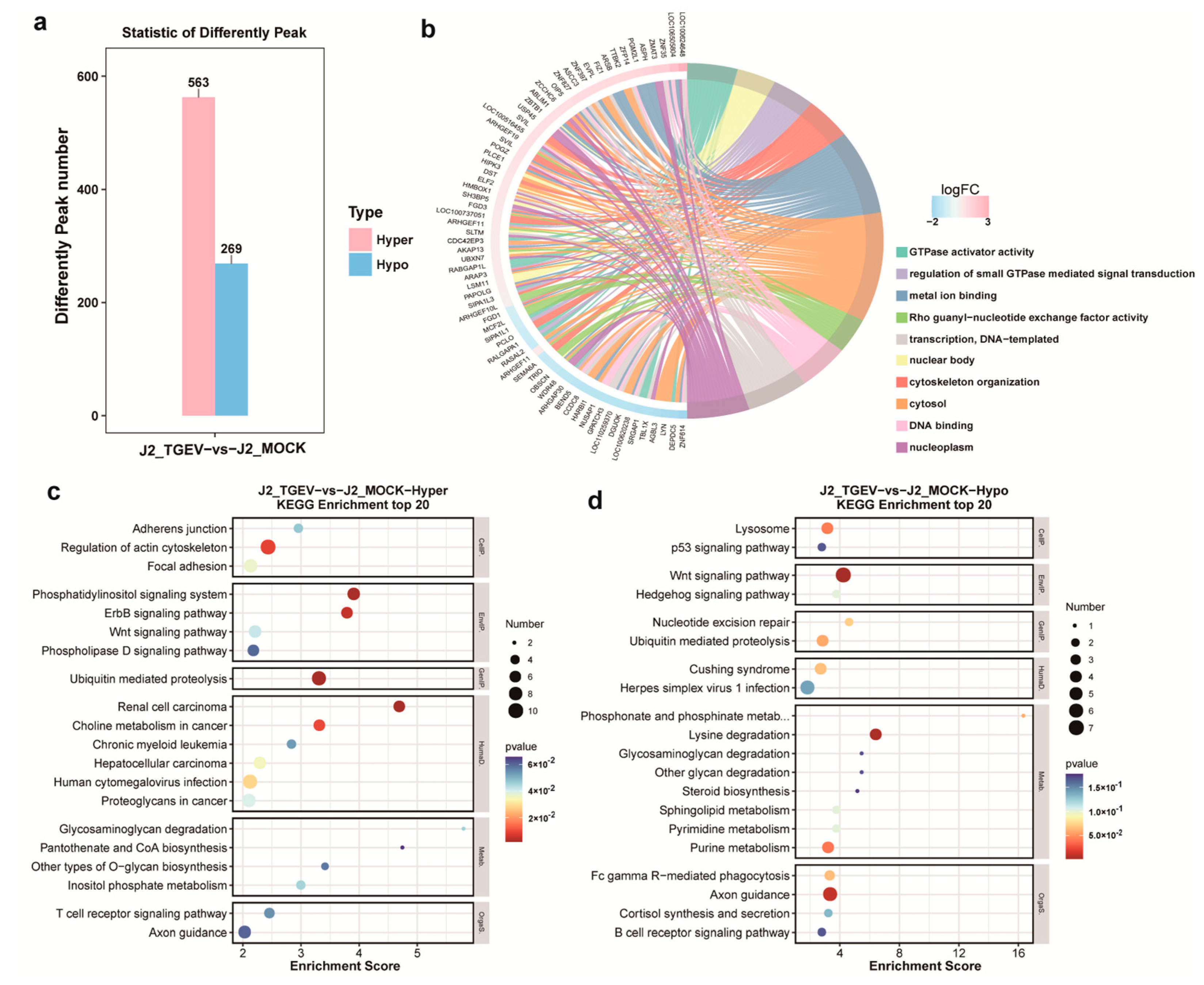

3.3. Pathway Enrichment Analysis of m6A-Methylated Genes

3.4. Identification of Transcriptional Changes in TGEV-Infected Cells

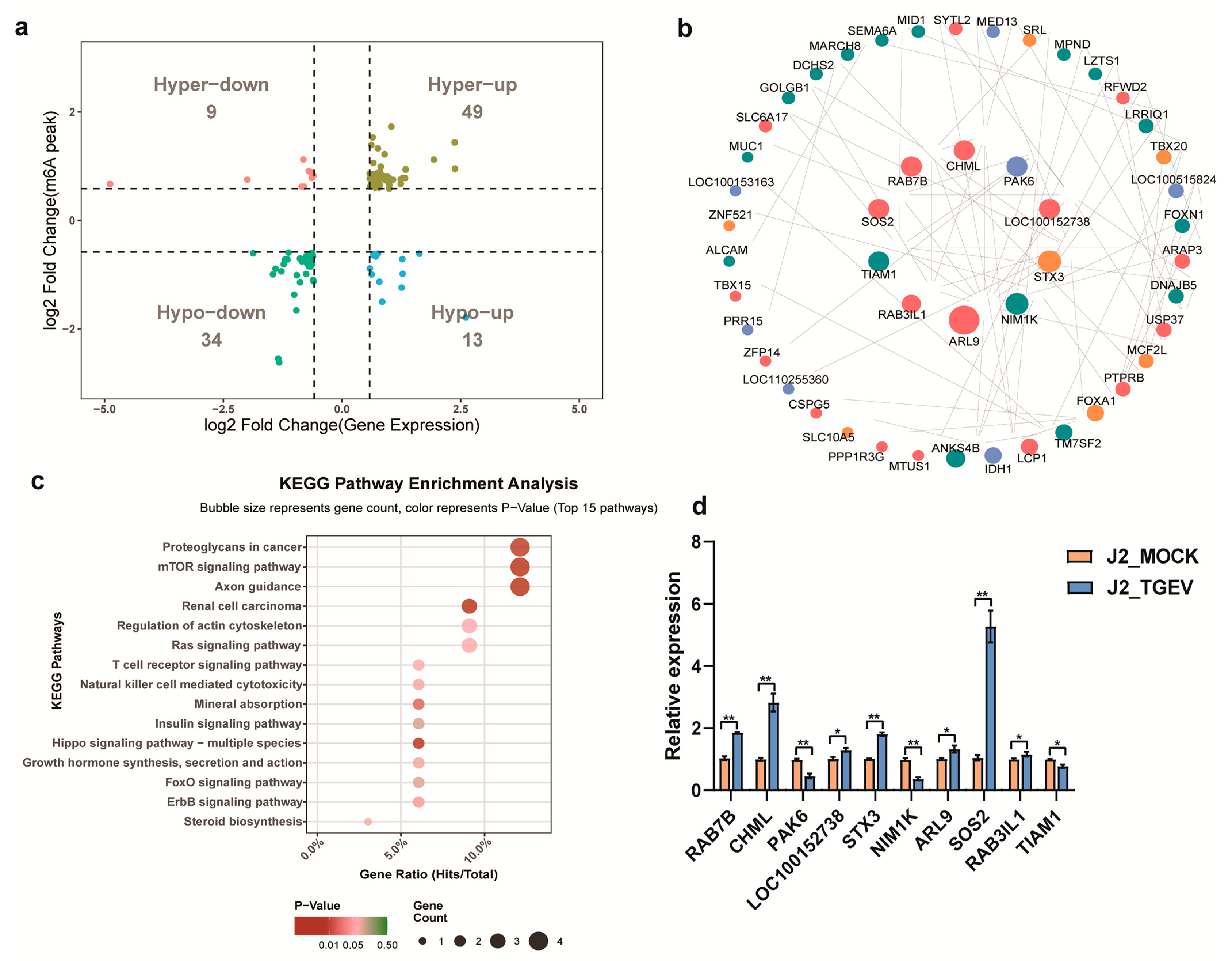

3.5. Conjoint Analysis of m6A-RIP-Seq and RNA-Seq Data

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Olech, M.; Antas, M. Transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV) and porcine respiratory coronavirus (PRCV): Epidemiology and molecular characteristics-an updated overview. Viruses 2025, 17, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crespo, F.I.; Mayora, S.J.; De Sanctis, J.B.; Martínez, W.Y.; Zabaleta-Lanz, M.E.; Toro, F.I.; Deibis, L.H.; García, A.H. SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Venezuelan Pediatric Patients-A Single Center Prospective Observational Study. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamau, E.; Bessaud, M.; Majumdar, M.; Martin, J.; Simmonds, P.; Harvala, H. Estimating prevalence of Enterovirus D111 in human and non-human primate populations using cross-sectional serology. J. Gen. Virol. 2023, 104, 001915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhou, J.; Ma, L.; Li, J.; Yang, L.; Ouyang, H.; Yuan, H.; Pang, D. Transmissible Gastroenteritis Virus: An Update Review and Perspective. Viruses 2023, 15, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turlewicz-Podbielska, H.; Pomorska-Mol, M. Porcine coronaviruses: Overview of the state of the art. Virol. Sin. 2021, 36, 833–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, N.; Li, Y.; Tan, C.; Cai, Y.; Rui, X.; Liu, Y.; Fu, Y.; Liu, G. Transmissible gastroenteritis virus induces inflammatory responses via RIG-I/NF-κB/HIF-1α/glycolysis axis in intestinal organoids and in vivo. J. Virol. 2024, 98, e0046124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, J.; Chen, D.; Tian, G.; He, J.; Zheng, P.; Huang, Z.; Mao, X.; Yu, J.; Luo, Y.; Luo, J.; et al. All-trans retinoic acid alleviates transmissible gastroenteritis virus-induced intestinal inflammation and barrier dysfunction in weaned piglets. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2024, 15, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antas, M.; Olech, M. First report of transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV) and porcine respiratory coronavirus (PRCV) in pigs from Poland. BMC Vet. Res. 2024, 20, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xiong, X.; Yi, C. Epitranscriptome sequencing technologies: Decoding RNA modifications. Nat. Methods 2016, 14, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lence, T.; Paolantoni, C.; Worpenberg, L.; Roignant, J.Y. Mechanistic insights into m6A RNA enzymes. BBA-Gene Regul. Mech. 2019, 1862, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominissini, D.; Moshitch-Moshkovitz, S.; Schwartz, S.; Salmon-Divon, M.; Ungar, L.; Osenberg, S.; Cesarkas, K.; Jacob-Hirsch, J.; Amariglio, N.; Kupiec, M.; et al. Topology of the human and mouse m6A RNA methylomes revealed by m6A-seq. Nature 2012, 485, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.; Dahl, J.A.; Niu, Y.; Fedorcsak, P.; Huang, C.M.; Li, C.J.; Vågbø, C.B.; Shi, Y.; Wang, W.L.; Song, S.H.; et al. ALKBH5 is a mammalian RNA demethylase that impacts RNA metabolism and mouse fertility. Mol. Cell 2013, 49, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Hsu, P.J.; Chen, Y.S.; Yang, Y.G. Dynamic transcriptomic m6A decoration: Writers, erasers, readers and functions in RNA metabolism. Cell Res. 2018, 28, 616–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, H.J.; Hao, S.J.; Chen, H.H.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Y.F.; Wang, J.; Wang, H.Z.; Zhang, B.; Qiu, J.M.; Deng, F.; et al. N6-methyladenosine modification and METTL3 modulate enterovirus 71 replication. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, 362–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durbin, A.F.; Wang, C.; Marcotrigiano, J.; Gehrke, L. RNAs containing modified nucleotides fail to trigger RIG-I conformational changes for innate immune signaling. mBio 2016, 7, e00833-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karikó, K.; Buckstein, M.; Ni, H.; Weissman, D. Suppression of RNA recognition by Toll-like receptors: The impact of nucleoside modification and the evolutionary origin of RNA. Immunity 2005, 23, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heng, J.; Tian, M.; Zhang, W.; Chen, F.; Guan, W.; Zhang, S. Maternal heat stress regulates the early fat deposition partly through modification of m6A RNA methylation in neonatal piglets. Cell Stress Chaperones 2019, 24, 635–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, N.A.; Li, X.M.; Yu, J.Y.; Li, Y. Curcumin Attenuates Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Hepatic Lipid Metabolism Disorder by Modification of m6A RNA Methylation in Piglets. Lipids 2018, 53, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.F.; Liu, Y.H.; Zhao, Y.L.; Bi, Z.; Yao, Y.X.; Liu, Q.; Wang, F.Q.; Wang, Y.Z.; Wang, X.X. m6A methylation controls pluripotency of porcine induced pluripotent stem cells by targeting SOCS3/JAK2/STAT3 pathway in a YTHDF1/YTHDF2-orchestrated manner. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Wang, H.; Liu, R.; He, M.N.; Che, T.D.; Jin, L.; Deng, L.M.; Tian, S.L.; Li, Y.; Lu, H.F.; et al. mRNA N6-methyladenosine methylation of postnatal liver development in pig. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0173421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Dominissini, D.; Rechavi, G.; He, C. Gene Expression Regulation Mediated through Reversible m6A RNA Methylation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2014, 15, 293–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adhikari, S.; Xiao, W.; Zhao, Y.L.; Yang, Y.G. m6A: Signaling for mRNA Splicing. RNA Biol. 2016, 13, 756–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebastian-delaCruz, M.; Olazagoitia-Garmendia, A.; Gonzalez-Moro, I.; Santin, I.; Garcia-Etxebarria, K.; Castellanos-Rubio, A. Implication of m6A mRNA Methylation in Susceptibility to Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Epigenomes 2020, 4, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.; Chen, W.; He, J.; Jin, S.; Liu, Y.; Yi, Y.; Gao, Z.; Yang, J.; Yang, J.; Cui, J.; et al. Interplay of m6A and H3K27 Trimethylation Restrains Inflammation during Bacterial Infection. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaba0647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Xu, C.; Gu, S.; Xiao, Y.; Wu, S.; Wang, H.; Bao, W. Integrated Metabolomic and transcriptomic analyses reveal deoxycholic acid promotes transmissible gastroenteritis virus infection by inhibiting phosphorylation of NF-κB and STAT3. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Cao, Y.; Xu, C.; Wang, G.; Huang, Y.; Bao, W.; Zhang, S. Integrated metabolomics and transcriptomics analyses reveal metabolic responses to TGEV infection in porcine intestinal epithelial cells. J. Gen. Virol. 2023, 104, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Shi, X.; Wu, L.; Wu, Z.; Wu, S.; Bao, W. Genome-Wide DNA Methylome and Transcriptome Analysis of Porcine Testicular Cells Infected with Transmissible Gastroenteritis Virus. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 8, 779323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominissini, D.; Moshitch-Moshkovitz, S.; Salmon-Divon, M.; Amariglio, N.; Rechavi, G. Transcriptome-wide mapping of N6-methyladenosine by m6A-seq based on immunocapturing and massively parallel sequencing. Nat. Protoc. 2013, 8, 176–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet. J. 2011, 17, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. HISAT: A fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, T.; Meyer, C.A.; Eeckhoute, J.; Johnson, D.S.; Bernstein, B.E.; Nusbaum, C.; Myers, R.M.; Brown, M.; Li, W.; et al. Model-based Analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS). Genome Biol. 2008, 9, R137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Shao, N.Y.; Liu, X.; Maze, I.; Feng, J.; Nestler, E.J. diffReps: Detecting differential chromatin modifification sites from ChIP-seq data with biological replicates. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e65598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorvaldsdottir, H.; Robinson, J.T.; Mesirov, J.P. Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV): High-performance genomics data visualization and exploration. Brief Bioinform. 2013, 14, 178–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shannon, P.; Markiel, A.; Ozier, O.; Baliga, N.S.; Wang, J.T.; Ramage, D.; Amin, N.; Schwikowski, B.; Ideker, T. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003, 13, 2498–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Liu, Y.; Song, R.; Zhao, L.; Yang, J.; Lu, F.; Cao, X. RNA 2’-O-methyltransferase Fibrillarin facilitates virus entry into macrophages through inhibiting type I interferon response. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 793582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, W.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, R.; Lu, Y.; Wang, X.; Tian, H.; Yang, Y.; Gu, Z.; Gao, Y.; Yang, X.; et al. N6-methyladenosine RNA modification suppresses antiviral innate sensing pathways via reshaping double-stranded RNA. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, G.D.; Gokhale, N.S.; Horner, S.M. Regulation of viral infection by the RNA modification N6-Methyladenosine. Ann. Rev. Virol. 2019, 6, 235–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Peng, Q.; Wang, L. N6-methyladenosine modification-a key player in viral infection. Cell Mol. Biol. Lett. 2023, 28, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Xu, Z.; Lu, L.; Zeng, T.; Gu, L.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Yang, P.; Wen, Y.; Lin, D.; et al. Transcriptome-wide study revealed m6A regulation of embryonic muscle development in Dingan goose (Ansercygnoides orientalis). BMC Genom. 2021, 22, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, X.; Chen, J.; Jiang, Y.; Wei, Y.; Chen, Y.; Xu, H.; Zhu, L.; Tang, G.; Li, M.; Jiang, A.; et al. Transcriptome-wide N6-methyladenosine methylome profiling of porcine muscle and adipose tissues reveals a potential mechanism for transcriptional regulation and differential methylation pattern. BMC Genom. 2017, 18, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhu, G. Profiling of RNA N6-methyladenosine methylation during follicle selection in chicken ovary. Poult. Sci. 2019, 98, 6117–6124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Q.; Yao, Z.; Chen, L.; He, Y.; Xie, Z.; Zhang, H.; Lin, W.; Chen, F.; Xie, Q.; Zhang, X. Transcriptome-wide dynamics of m6A methylation in tumor livers induced by ALV-J infection in Chickens. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 868892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Q.; Gui, Y.; Ma, X.; Zhang, B.; Xiong, W.; Yang, S.; Cao, C.; Mo, S.; Shu, G.; Ye, J.; et al. N6-methyladenosine writer METTL16-mediated alternative splicing and translation control are essential for murine spermatogenesis. Genome Biol. 2024, 25, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Sun, J.; Lin, Z.; Zhang, W.; Wang, S.; Wang, W.; Wang, Q.; Ning, G. m6A mRNA Methylation Controls Functional Maturation in Neonatal Murine β-Cells. Diabetes 2020, 69, 1708–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayr, C. What Are 3′ UTRs Doing? Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2019, 11, a034728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, W.V.; Bell, T.A.; Schaening, C. Messenger RNA modifications: Form, distribution, and function. Science 2016, 352, 1408–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warda, A.S.; Kretschmer, J.; Hackert, P.; Lenz, C.; Urlaub, H.; Hobartner, C.; Sloan, K.E.; Bohnsack, M.T. Human METTL16 is a N6-methyladenosine (m6A) methyltransferase that targets pre-mRNAs and various non-coding RNAs. EMBO Rep. 2017, 18, 2004–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Gong, L.; Zhang, W.; Chen, W.; Pan, H.; Zeng, Y.; Liang, X.; Ma, J.; Zhang, G.; Wang, H. Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway inhibits porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus replication by enhancing the nuclear factor-κB-dependent innate immune response. Vet. Microbiol. 2020, 251, 108904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Ghosh, S.; Datey, A.; Mahish, C.; Chattopadhyay, S.; Chattopadhyay, S. Chikungunya virus perturbs the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway for efficient viral infection. J. Virol. 2023, 97, e0143023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- More, S.; Yang, X.; Zhu, Z.; Bamunuarachchi, G.; Guo, Y.; Huang, C.; Bailey, K.; Metcalf, J.P.; Liu, L. Regulation of influenza virus replication by Wnt/β-catenin signaling. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0191010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, Y.; Li, Y.; Yang, S.; Chen, J.; Liu, G. Transmissible Gastroenteritis Virus Infection Promotes the Self-Renewal of Porcine Intestinal Stem Cells via Wnt/β-Catenin Pathway. J. Virol. 2022, 96, e0096222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wu, S.; Xia, Y.; Li, X.E.; Xia, Y.; Zhou, Z.D.; Sun, J. Wingless homolog Wnt11 suppresses bacterial invasion and inflammation in intestinal epithelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2011, 301, G992–G1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, H.; Yao, Q.; Ba, J.; Luan, J.; Zhao, P.; Qin, Z.; Qi, Z. mTOR signaling regulates Zika virus replication bidirectionally through autophagy and protein translation. J. Med. Virol. 2023, 95, e28422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wei, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Meng, Z.; Lu, M. mTOR Signaling: The Interface Linking Cellular Metabolism and Hepatitis B Virus Replication. Virol. Sin. 2021, 36, 1303–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossler, F.; Hoppe-Seyler, K.; Hoppe-Seyler, F. PI3K/AKT/mTOR Signaling Regulates the Virus/Host Cell Crosstalk in HPV-Positive Cervical Cancer Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Chen, D.; Yu, B.; He, J.; Yu, J.; Mao, X.; Luo, Y.; Zheng, P.; Luo, J. L-Leucine Promotes STAT1 and ISGs Expression in TGEV-Infected IPEC-J2 Cells via mTOR Activation. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 656573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, Y.; Zhou, G.; Wang, G.; Wu, Z. Transcriptome-Wide Identification and Analysis Reveals m6A Regulation of Porcine Intestinal Epithelial Cells Under TGEV Infection. Vet. Sci. 2026, 13, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010010

Liu Y, Zhou G, Wang G, Wu Z. Transcriptome-Wide Identification and Analysis Reveals m6A Regulation of Porcine Intestinal Epithelial Cells Under TGEV Infection. Veterinary Sciences. 2026; 13(1):10. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010010

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Ying, Gang Zhou, Guolian Wang, and Zhengchang Wu. 2026. "Transcriptome-Wide Identification and Analysis Reveals m6A Regulation of Porcine Intestinal Epithelial Cells Under TGEV Infection" Veterinary Sciences 13, no. 1: 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010010

APA StyleLiu, Y., Zhou, G., Wang, G., & Wu, Z. (2026). Transcriptome-Wide Identification and Analysis Reveals m6A Regulation of Porcine Intestinal Epithelial Cells Under TGEV Infection. Veterinary Sciences, 13(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010010