Changes in Fitness Parameters in Ridden Trained Showjumping Horses After Healing of Gastric Ulcers: Preliminary Results

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

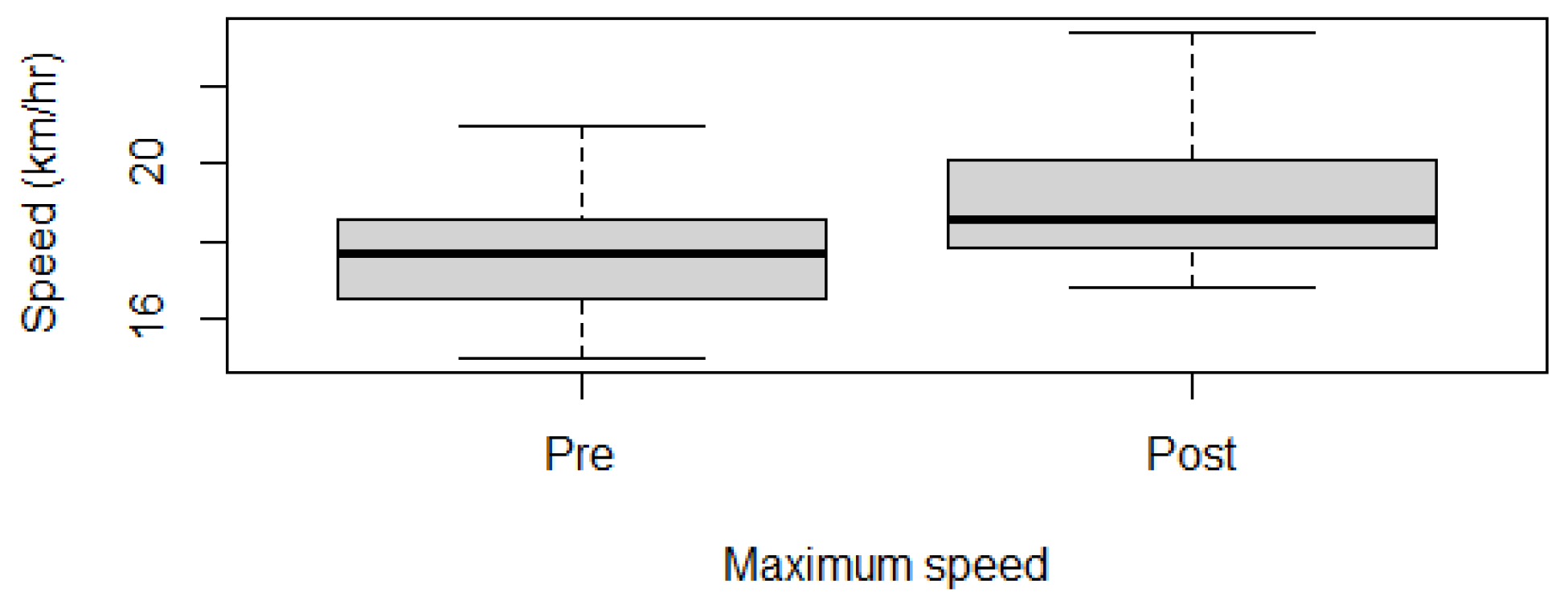

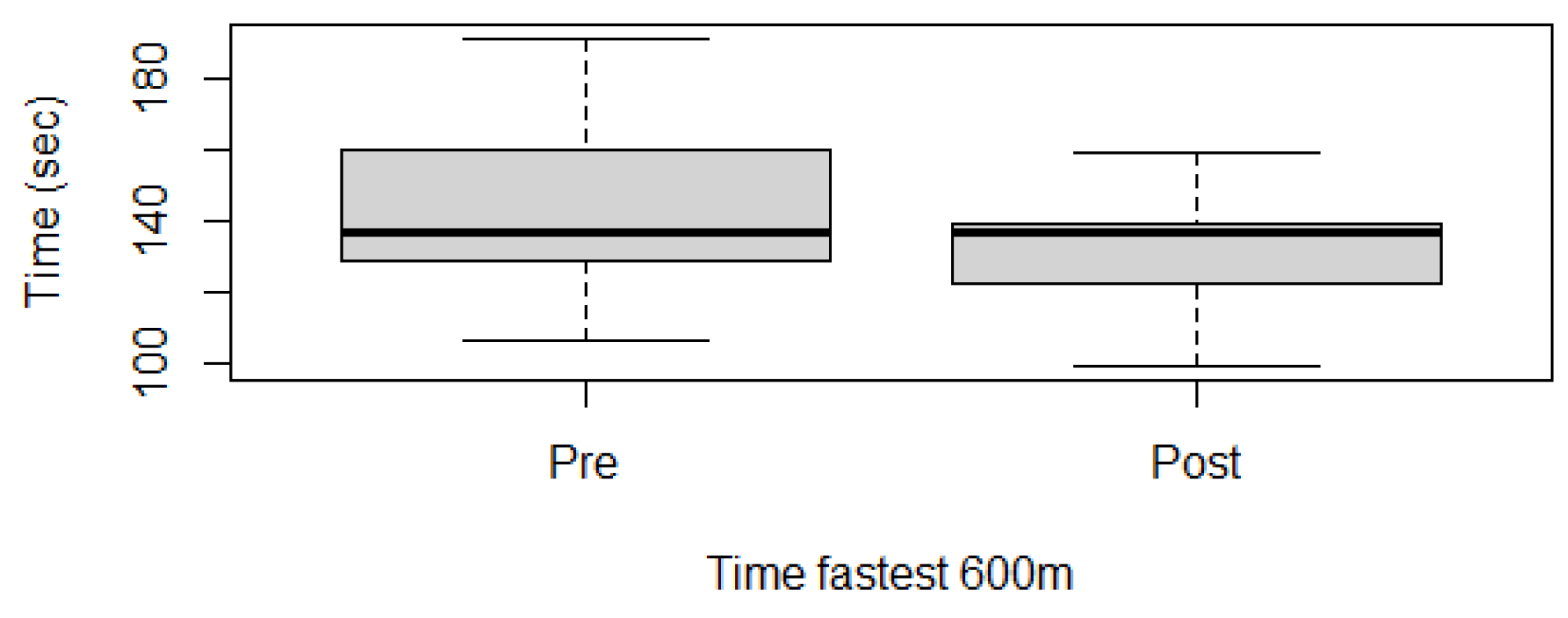

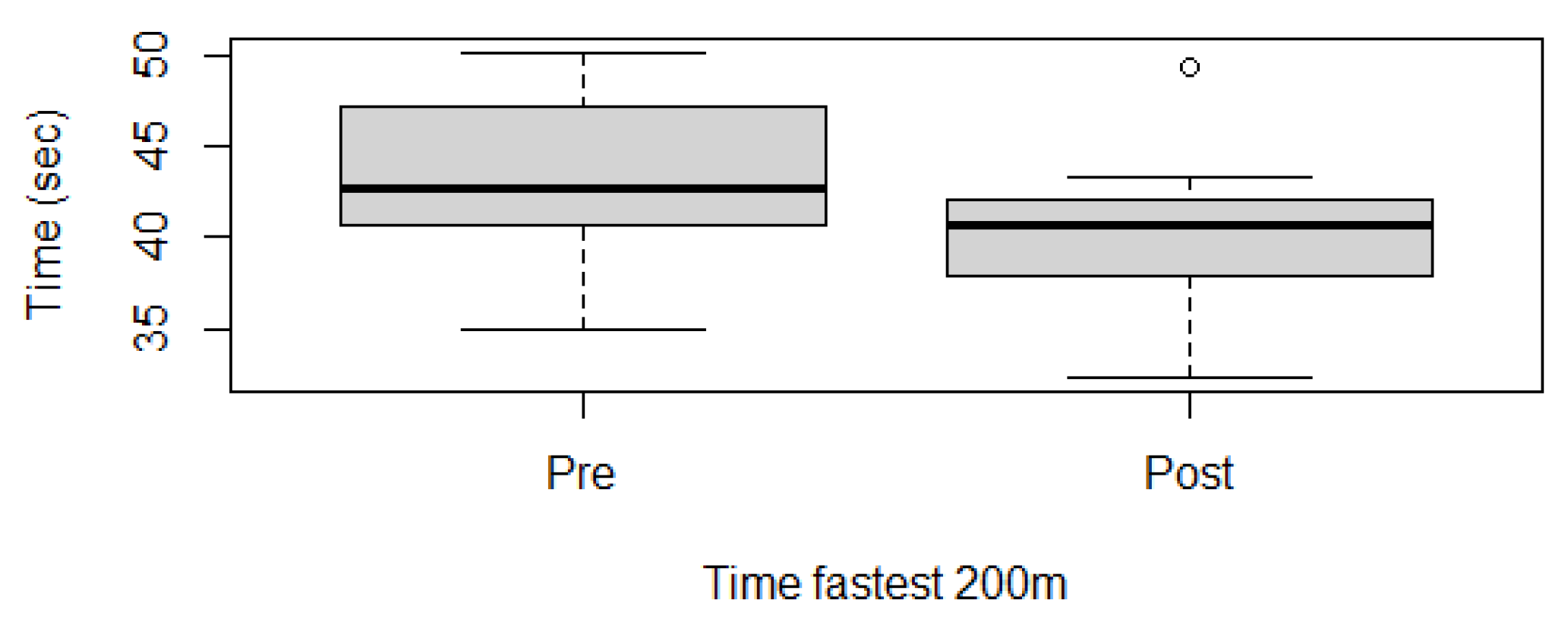

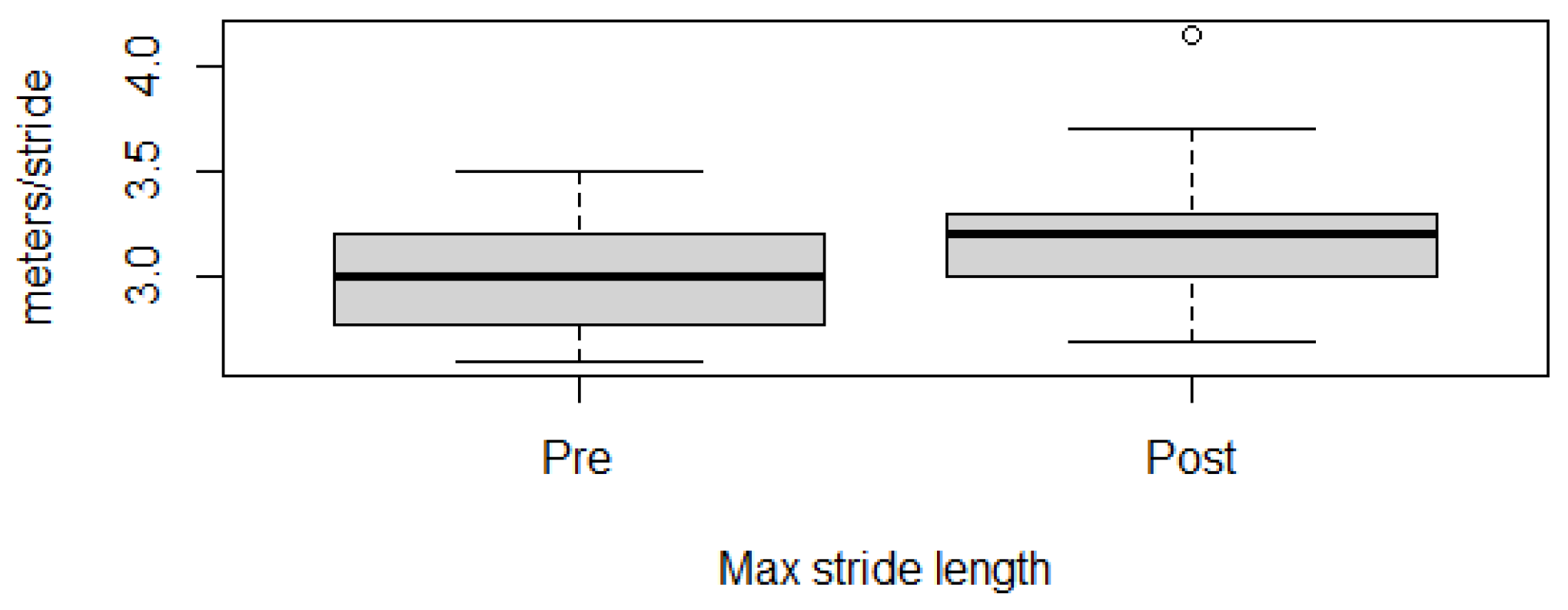

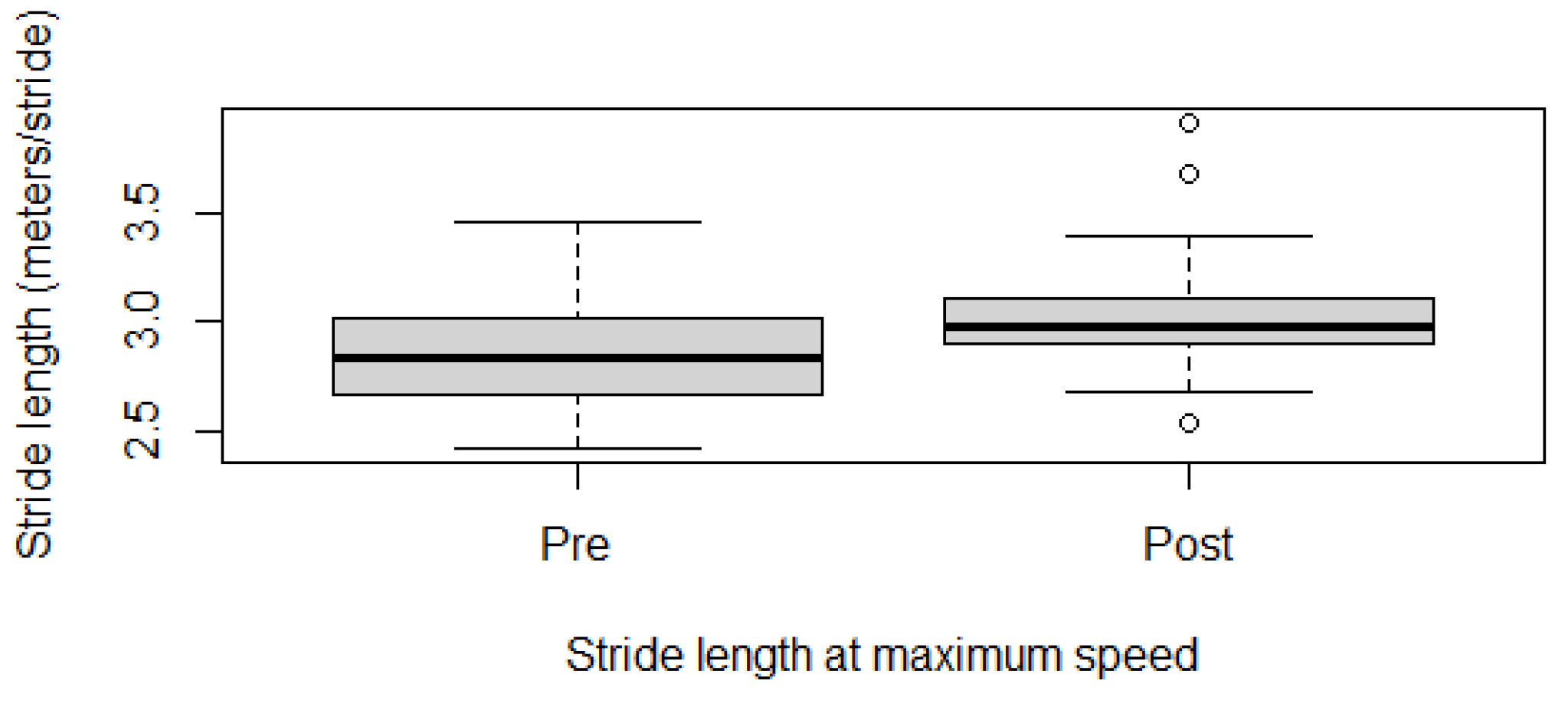

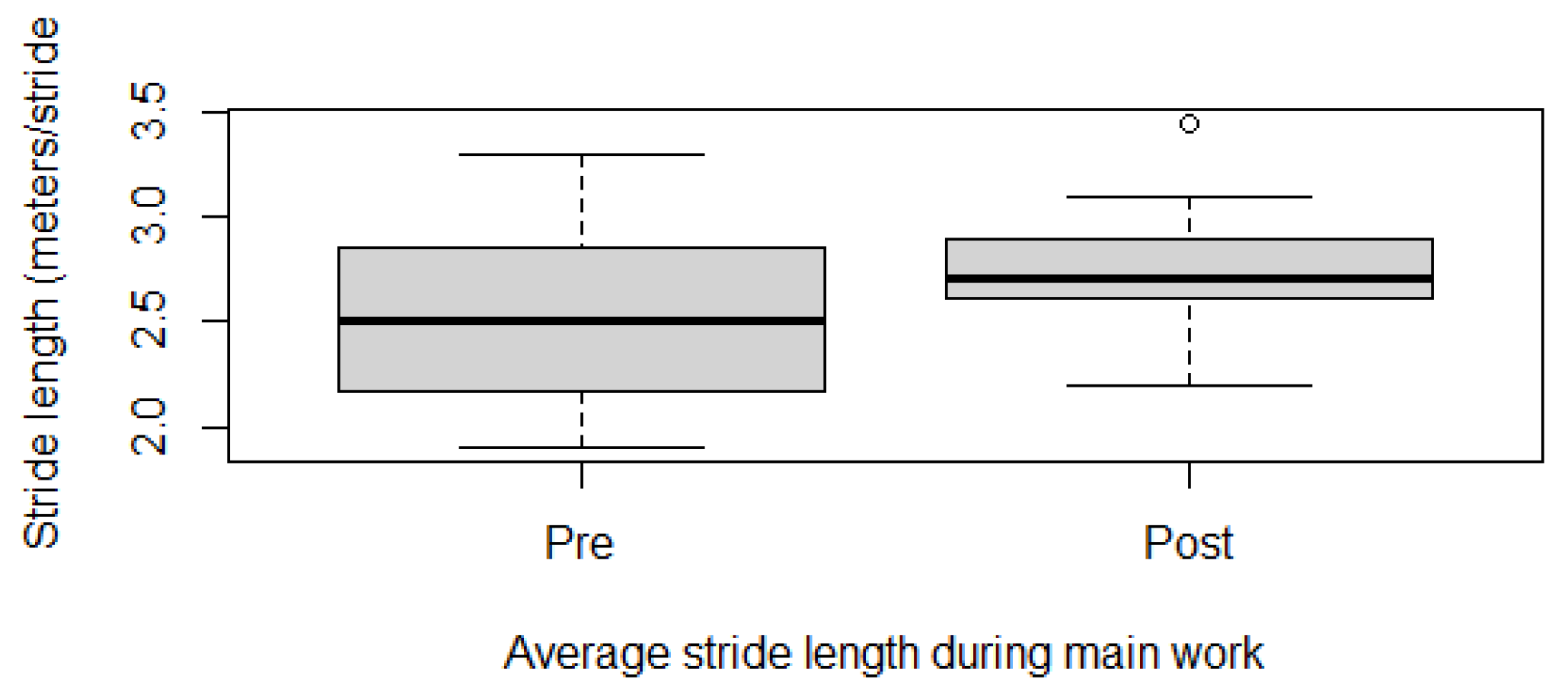

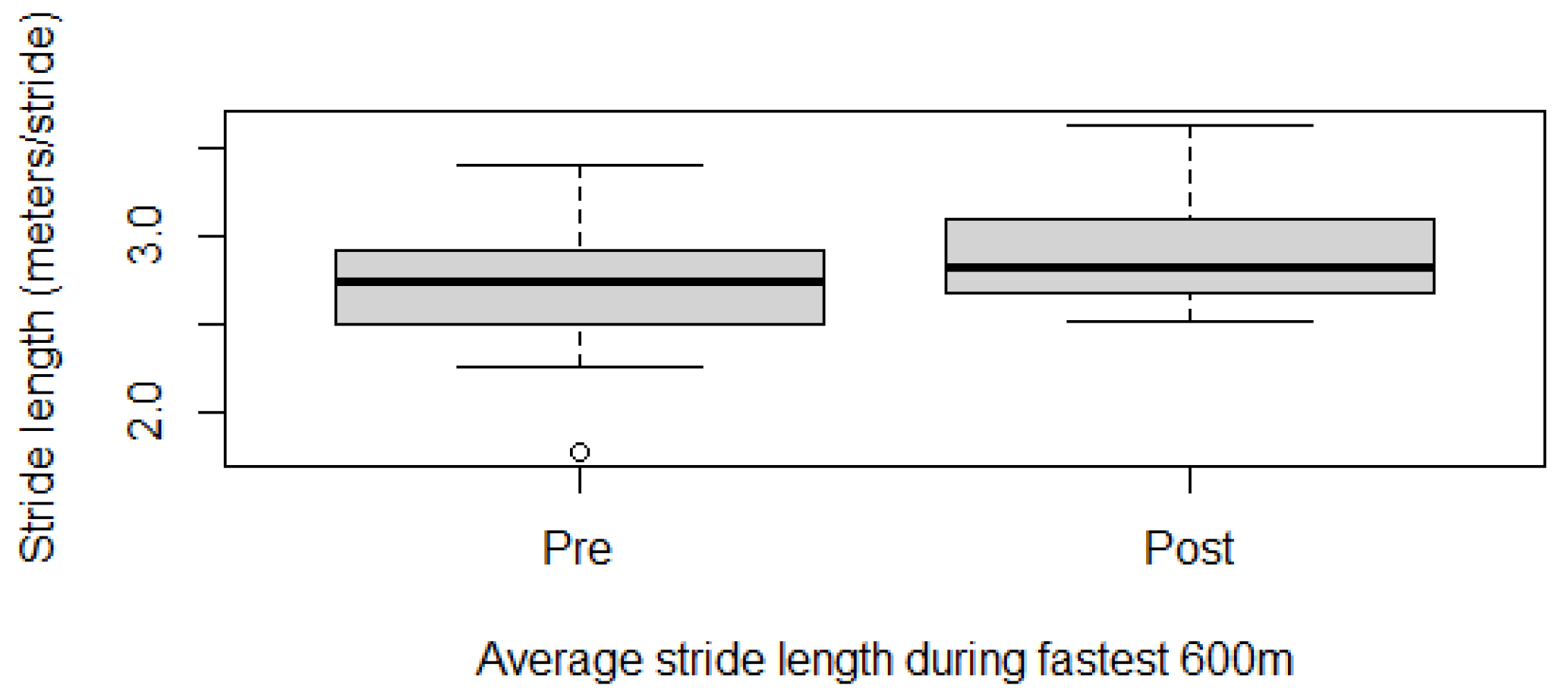

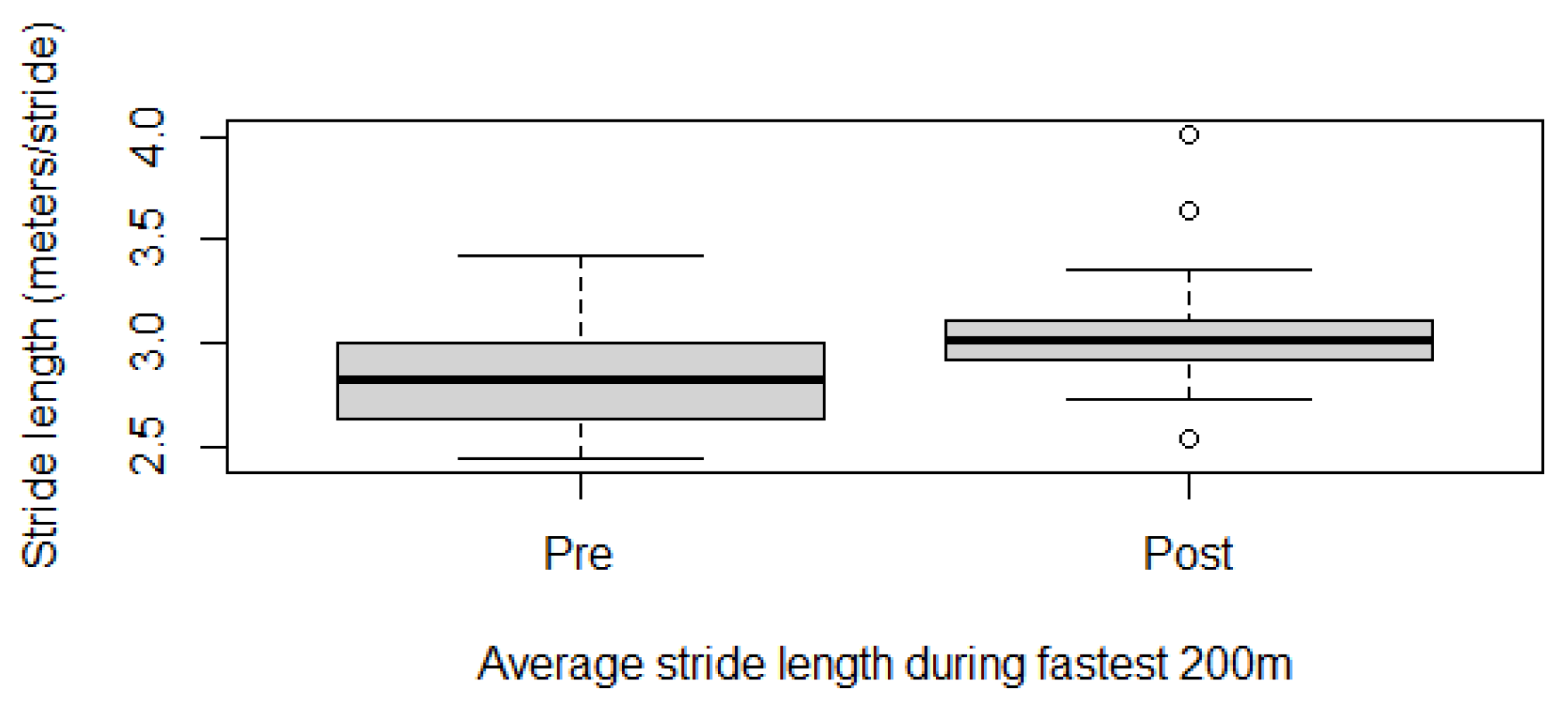

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sykes, B.W.; Hewetson, M.; Hepburn, R.J.; Luthersson, N.; Tamzali, Y. European College of Equine Internal Medicine Consensus Statement—Equine Gastric Ulcer Syndrome in Adult Horses. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2015, 29, 1288–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendle, D.; Bowen, M.; Brazil, T.; Conwell, R.; Hallowell, G.; Hepburn, R.; Hewetson, M.; Sykes, B. Recommendations for the Management of Equine Glandular Gastric Disease. UK-Vet Equine 2018, 2, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Boom, R. Equine Gastric Ulcer Syndrome in Adult Horses. Vet. J. 2022, 283–284, 105830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vokes, J.; Lovett, A.; Sykes, B. Equine Gastric Ulcer Syndrome: An Update on Current Knowledge. Animals 2023, 13, 1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sykes, B.W.; Bowen, M.; Habershon-Butcher, J.L.; Green, M.; Hallowell, G.D. Management Factors and Clinical Implications of Glandular and Squamous Gastric Disease in Horses. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2019, 33, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, H.; Dong, H.-J.; Han, J.; Cho, S.; Kim, Y.; Lee, I. Prevalence and Treatment of Gastric Ulcers in Thoroughbred Racehorses of Korea. J. Vet. Sci. 2021, 23, e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, S.K.; Cribb, A.E.; Windeyer, M.C.; Read, E.K.; French, D.; Banse, H.E. Risk Factors for Equine Glandular and Squamous Gastric Disease in Show Jumping Warmbloods. Equine Vet. J. 2018, 50, 747–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedźwiedź, A.; Kubiak, K.; Nicpoń, J. Endoscopic Findings of the Stomach in Pleasure Horses in Poland. Acta Vet. Scand. 2013, 55, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busechian, S.; Bindi, F.; Orvieto, S.; Zappulla, F.; Marchesi, M.C.; Nisi, I.; Rueca, F. Prevalence and Risk Factors for the Presence of Gastric Ulcers in Pleasure and Breeding Horses in Italy. Animals 2024, 14, 1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chameroy, K.A.; Nadeau, J.A.; Bushmich, S.L.; Dinger, J.E.; Hoagland, T.A.; Saxton, A.M. Prevalence of Non-Glandular Gastric Ulcers in Horses Involved in a University Riding Program. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2006, 26, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busechian, S.; Bindi, F.; Pieramati, C.; Orvieto, S.; Pisello, L.; Cozzi, S.; Ortolani, F.; Rueca, F. Is There a Difference in the Prevalence of Gastric Ulcers between Stallions Used for Breeding and Those Not Used for Breeding? Animals 2024, 14, 1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertone, J. Prevalence of Gastric Ulcers in Elite, Heavy Use Western Performance Horses. In Proceedings of the 48th Annual AAEP Convention, Orlando, FL, USA, 4–8 December 2002; pp. 256–259. [Google Scholar]

- Millares-Ramirez, E.M.; Le Jeune, S.S. Girthiness: Retrospective Study of 37 Horses (2004–2016). J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2019, 79, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, S.H.; Brazil, T.J.; Allen, K.J. Poor Performance Associated with Equine Gastric Ulceration Syndrome in Four Thoroughbred Racehorses. Equine Vet. Educ. 2008, 20, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Feudo, C.M.; Stucchi, L.; Stancari, G.; Conturba, B.; Bozzola, C.; Zucca, E.; Ferrucci, F. Associations between Medical Disorders and Racing Outcomes in Poorly Performing Standardbred Trotter Racehorses: A Retrospective Study. Animals 2023, 13, 2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Feudo, C.M.; Stucchi, L.; Conturba, B.; Stancari, G.; Zucca, E.; Ferrucci, F. Equine Gastric Ulcer Syndrome Affects Fitness Parameters in Poorly Performing Standardbred Racehorses. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 1014619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo Feudo, C.M.; Stucchi, L.; Conturba, B.; Stancari, G.; Zucca, E.; Ferrucci, F. Medical Causes of Poor Performance and Their Associations with Fitness in Standardbred Racehorses. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2023, 37, 1514–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto, J.E.; Snyder, J.R.; Vatistas, N.J.; Jones, J.H. Effect of Gastric Ulceration on Physiologic Responses to Exercise in Horses. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2009, 70, 787–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Erck-Westergren, E. Exercise Testing in the Field. In Equine Sports Medicine and Surgery; Elsevier: St. Louis, MI, USA, 2024; pp. 58–82. [Google Scholar]

- Van Erck-Westergren, E. The Connected Horse. In Equine Sports Medicine and Surgery; Elsevier: St. Louis, MI, USA, 2024; pp. 83–94. [Google Scholar]

- Kee, P.; Anderson, N.; Gargiulo, G.D.; Velie, B.D. A Synopsis of Wearable Commercially Available Biometric-Monitoring Devices and Their Potential Applications during Gallop Racing. Equine Vet. Educ. 2023, 35, 551–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, R.C. Veterinary Aspects of Conditioning, Training, and Competing the Showjumping Horse. In Equine Sports Medicine and Surgery; Elsevier: St. Louis, MI, USA, 2024; pp. 1228–1239. [Google Scholar]

- Busechian, S.; Sgorbini, M.; Orvieto, S.; Pisello, L.; Zappulla, F.; Briganti, A.; Nocera, I.; Conte, G.; Rueca, F. Evaluation of a Questionnaire to Detect the Risk of Developing ESGD or EGGD in Horses. Prev. Vet. Med. 2021, 188, 105285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ter Woort, F.; Dubois, G.; Tansley, G.; Didier, M.; Verdegaal, L.; Franklin, S.; Van Erck-Westergren, E. Validation of an Equine Fitness Tracker: ECG Quality and Arrhythmia Detection. Equine Vet. J. 2022, 55, 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ter Woort, F.; Dubois, G.; Didier, M.; Van Erck-Westergren, E. Validation of an Equine Fitness Tracker: Heart Rate and Heart Rate Variability. Comp. Exerc. Physiol. 2021, 17, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyson, S. The Ridden Horse Pain Ethogram. Equine Vet. Educ. 2022, 34, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineau, V.; ter Woort, F.; Julien, F.; Vernant, M.; Lambey, S.; Hébert, C.; Hanne-Poujade, S.; Westergren, V.; van Erck-Westergren, E. Improvement of Gastric Disease and Ridden Horse Pain Ethogram Scores with Diet Adaptation in Sport Horses. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2024, 38, 3297–3308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A Flexible Statistical Power Analysis Program for the Social, Behavioral, and Biomedical Sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posit Team. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R; Posit Software, PBC: Boston, MA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Dionne, R.M.; Vrins, A.; Doucet, M.Y.; Pare, J. Gastric Ulcers in Standardbred Racehorses: Prevalence, Lesion Description, and Risk Factors. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2003, 17, 218–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekeux, P.; Art, T.; Linden, A.; Desmecht, D.; Amory, H. Heart Rate, Haematological and Serum Biochemical Responses to Show Jumping. In Equine Exercise Physiology 3 (Proceedings of the 3rd Int’l Conference on Equine Exercise Physiology); ICEEP Publications: Davis, CA, USA, 1991; pp. 385–390. [Google Scholar]

- Art, T.; Amory, H.; Desmecht, D.; Lekeux, P. Effect of Show Jumping on Heart Rate, Blood Lactate and Other Plasma Biochemical Values. Equine Vet. J. 1990, 22, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbst, A.C.; Coleman, M.C.; Macon, E.L.; Harris, P.A.; Adams, A.A. Demographics and Health of U.S. Senior Horses Used in Competitions. Equine Vet. J. 2025, 57, 1044–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munsters, C.C.B.M.; van Iwaarden, A.; van Weeren, R.; Sloet van Oldruitenborgh-Oosterbaan, M.M. Exercise Testing in Warmblood Sport Horses under Field Conditions. Vet. J. 2014, 202, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, A.S.M.; Morrice-West, A.V.; Whitton, R.C.; Hitchens, P.L. Changes in Thoroughbred Speed and Stride Characteristics over Successive Race Starts and Their Association with Musculoskeletal Injury. Equine Vet. J. 2023, 55, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinchcliff, K.W. The Horse as an Athlete. In Equine Sports Medicine and Surgery; Elsevier: St. Louis, MI, USA, 2024; pp. 23–31. [Google Scholar]

- Stucchi, L.; Alberti, E.; Stancari, G.; Conturba, B.; Zucca, E.; Ferrucci, F. The Relationship between Lung Inflammation and Aerobic Threshold in Standardbred Racehorses with Mild-Moderate Equine Asthma. Animals 2020, 10, 1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couëtil, L.L.; Cardwell, J.M.; Gerber, V.; Lavoie, J.-P.; Léguillette, R.; Richard, E.A. Inflammatory Airway Disease of Horses—Revised Consensus Statement. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2016, 30, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darbandi, H.; Munsters, C.; Parmentier, J.; Havinga, P. Detecting Fatigue of Sport Horses with Biomechanical Gait Features Using Inertial Sensors. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0284554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, Y.; Takahashi, T.; Mukai, K.; Ohmura, H. Effects of Fatigue on Stride Parameters in Thoroughbred Racehorses During Races. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2021, 101, 103447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickler, S.J.; Greene, H.M.; Egan, K.; Astudillo, A.; Dutto, D.J.; Hoyt, D.F. Stride Parameters and Hindlimb Length in Horses Fatigued on a Treadmill and at an Endurance Ride. Equine Vet. J. Suppl. 2006, 38, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrurs, C.; Blott, S.; Dubois, G.; Van Erck-Westergren, E.; Gardner, D.S. Locomotory Profiles in Thoroughbreds: Peak Stride Length and Frequency in Training and Association with Race Outcomes. Animals 2022, 12, 3269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKeever, J.M.; McKeever, K.H.; Albeirci, J.M.; Gordon, M.E.; Manso Filho, H.C. Effect of Omeprazole on Markers of Performance in Gastric Ulcer-Free Standardbred Horses. Equine Vet. J. Suppl. 2006, 38, 668–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Salvo, A.; Busechian, S.; Zappulla, F.; Marchesi, M.C.; Pieramati, C.; Orvieto, S.; Boveri, M.; Predieri, P.G.; Rueca, F.; Della Rocca, G. Pharmacokinetics and Tolerability of a New Formulation of Omeprazole in the Horse. J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 40, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Breed | Age | Sex | ESGD_t1 | ESGD_t2 | EGGD_t1 | EGGD_t2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Italian Saddlebred | 13 | male | 3 | 0 | neg | neg |

| German Saddlebred | 8 | gelding | 4 | 0 | pos | neg |

| German Saddlebred | 14 | gelding | 3 | 0 | pos | neg |

| Pony | 17 | gelding | 4 | 0 | pos | neg |

| French Saddlebred | 7 | gelding | 4 | 0 | neg | neg |

| Belgian Saddlebred | 7 | gelding | 4 | 0 | pos | neg |

| Belgian Saddlebred | 9 | gelding | 3 | 0 | neg | neg |

| Warmblood | 12 | gelding | 4 | 0 | neg | neg |

| Dutch warmblood | 11 | gelding | 3 | 0 | neg | neg |

| Irish warmblood | 11 | gelding | 3 | 0 | neg | neg |

| Pony | 20 | female | 3 | 0 | neg | neg |

| French Saddlebred | 12 | gelding | 3 | 0 | neg | neg |

| Italian Saddlebred | 10 | gelding | 4 | 2 | neg | neg |

| German Saddlebred | 9 | gelding | 4 | 2 | pos | neg |

| German Saddlebred | 11 | gelding | 4 | 0 | pos | neg |

| Dutch warmblood | 17 | gelding | 4 | 0 | pos | neg |

| Italian Saddlebred | 8 | female | 4 | 0 | neg | neg |

| French Saddlebred | 11 | male | 3 | 0 | neg | neg |

| Belgian Saddlebred | 11 | gelding | 4 | 2 | neg | neg |

| Dutch warmblood | 22 | female | 4 | 0 | pos | neg |

| Pony | 12 | gelding | 4 | 4 | neg | neg |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Busechian, S.; Salvo, A.D.; Orvieto, S.; Rueca, F.; Villella, C.; Sollevanti, G.; Pieramati, C.; Nisi, I.; della Rocca, G. Changes in Fitness Parameters in Ridden Trained Showjumping Horses After Healing of Gastric Ulcers: Preliminary Results. Vet. Sci. 2026, 13, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010009

Busechian S, Salvo AD, Orvieto S, Rueca F, Villella C, Sollevanti G, Pieramati C, Nisi I, della Rocca G. Changes in Fitness Parameters in Ridden Trained Showjumping Horses After Healing of Gastric Ulcers: Preliminary Results. Veterinary Sciences. 2026; 13(1):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010009

Chicago/Turabian StyleBusechian, Sara, Alessandra Di Salvo, Simona Orvieto, Fabrizio Rueca, Chiara Villella, Gaia Sollevanti, Camillo Pieramati, Irma Nisi, and Giorgia della Rocca. 2026. "Changes in Fitness Parameters in Ridden Trained Showjumping Horses After Healing of Gastric Ulcers: Preliminary Results" Veterinary Sciences 13, no. 1: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010009

APA StyleBusechian, S., Salvo, A. D., Orvieto, S., Rueca, F., Villella, C., Sollevanti, G., Pieramati, C., Nisi, I., & della Rocca, G. (2026). Changes in Fitness Parameters in Ridden Trained Showjumping Horses After Healing of Gastric Ulcers: Preliminary Results. Veterinary Sciences, 13(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010009