Risk Factors and Protection Associated with Well-Being and Psychological Distress of Veterinarians in Brazil

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

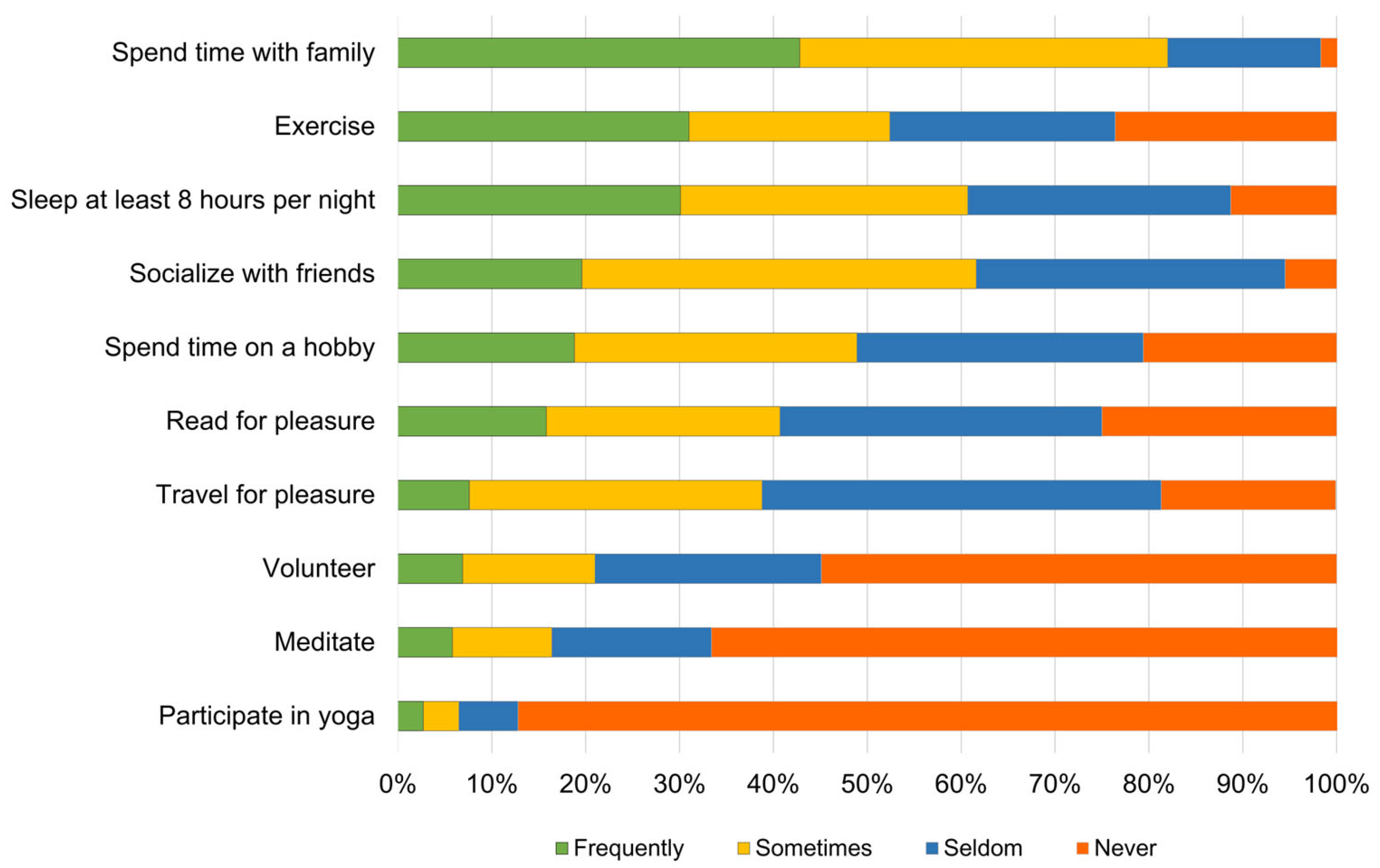

3.1. Sociodemographic, Occupational, and Mental Health Outcomes

3.2. Sociodemographic and Occupational Factors as Predictors of Mental Health Outcomes

3.3. Coping Strategies as Predictors of Mental Health Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Peixoto, M.M. Suicide risk in veterinary professionals in Portugal: Prevalence of psychological symptoms, burnout, and compassion fatigue. Arch. Suicide Res. 2024, 29, 439–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, M.F.; Kho, M.; Thomas, E.F.; Decety, J.; Molenberghs, P.; Amiot, C.E.; Lizzio-Wilson, M.; Wibisono, S.; Allan, F.; Louis, W. The moderating role of different forms of empathy on the association between performing animal euthanasia and career sustainability. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2023, 53, 1088–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira Bergamini, S.; Uccheddu, S.; Riggio, G.; de Jesus Vilela, M.R.; Mariti, C. The emotional impact of patient loss on brazilian veterinarians. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knesl, O.; Hart, B.L.; Fine, A.H.; Cooper, L.; Patterson-Kane, E.; Houlihan, K.E.; Anthony, R. Veterinarians and humane endings: When is it the right time to euthanize a companion animal? Front. Vet. Sci. 2017, 4, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volk, J.O.; Schimmack, U.; Strand, E.B.; Reinhard, A.; Hahn, J.; Andrews, J.; Probyn-Smith, K.; Jones, R. Work-life balance is essential to reducing burnout, improving well-being. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2024, 262, 950–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansen, W.; Lockett, L.; Colville, T.; Uldahl, M.; De Briyne, N. Veterinarian—Chasing a dream job? A comparative survey on wellbeing and stress levels among European veterinarians between 2018 and 2023. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volk, J.O.; Schimmack, U.; Strand, E.B.; Reinhard, A.; Vasconcelos, J.; Hahn, J.; Stiefelmeyer, K.; Probyn-Smith, K. Executive summary of the Merck animal health veterinarian wellbeing study III and veterinary support staff study. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2022, 260, 1547–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smits, F.; Houdmont, J.; Hill, B.; Pickles, K. Mental wellbeing and psychosocial working conditions of autistic veterinary surgeons in the UK. Vet. Rec. 2023, 193, e3311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liss, D.J.; Kerl, M.E.; Tsai, C.-L. Factors associated with job satisfaction and engagement among credentialed small animal veterinary technicians in the United States. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2020, 257, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, P.; Mills, P.; Doneley, B. Relieving veterinarians’ workloads and stress: Leveraging Australia’s veterinary technologists and nurses. Aust. Vet. J. 2023, 101, 409–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, C.O.; Perret, J.L.; Hewson, J.; Khosa, D.K.; Conlon, P.D.; Jones-Bitton, A. A survey of veterinarian mental health and resilience in Ontario, Canada. Can. Vet. J. 2020, 61, 166. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wouk, A.F.P.; Martins, C.M.; Mondadori, R.G.; Pacheco, M.H.d.S.; Molina, T.G.; Silveira, M.B.G.d.; Ferreira, F. Demographics of Veterinary Medicine in Brazil 2022; Editora Guará: Cotia, SP, Brazil, 2023; ISBN 978-85-87925-04-6. [Google Scholar]

- Bilodeau, J.; Marchand, A.; Demers, A. Psychological distress inequality between employed men and women: A gendered exposure model. SSM Popul. Health 2020, 11, 100626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steffey, M.A.; Griffon, D.J.; Risselada, M.; Buote, N.J.; Scharf, V.F.; Zamprogno, H.; Winter, A.L. A narrative review of the physiology and health effects of burnout associated with veterinarian-pertinent occupational stressors. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1184525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedhammer, I.; Bertrais, S.; Witt, K. Psychosocial work exposures and health outcomes: A meta-review of 72 literature reviews with meta-analysis. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2021, 47, 489–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goh, J.; Pfeffer, J.; Zenios, S.A. The relationship between workplace stressors and mortality and health costs in the United States. Manag. Sci. 2016, 62, 608–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, M.J.C.; Sequeira, C.A. Positive and Negative Correlates of Psychological Well-Being and Distress in College Students’ Mental Health: A Correlational Study. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohl, R.; Botscharow, J.; Böckelmann, I.; Thielmann, B. Stress and strain among veterinarians: A scoping review. Ir. Vet. J. 2022, 75, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubauer, V.; Dale, R.; Probst, T.; Pieh, C.; Janowitz, K.; Brühl, D.; Humer, E. Prevalence of mental health symptoms in Austrian veterinarians and examination of influencing factors. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 1984; ISBN 978-0-8261-4192-7. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasi, S.E.; Fechter-Leggett, E.D.; Edwards, N.T.; Reddish, A.D.; Crosby, A.E.; Nett, R.J. Suicide among veterinarians in the United States from 1979 through 2015. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2019, 254, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stetina, B.U.; Krouzecky, C. Reviewing a decade of change for veterinarians: Past, present and gaps in researching stress, coping and mental health risks. Animals 2022, 12, 3199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volk, J.O.; Schimmack, U.; Strand, E.B.; Lord, L.K.; Siren, C.W. Executive summary of the Merck animal health veterinary wellbeing study. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2018, 252, 1231–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kettle, V.E.; Madigan, C.D.; Coombe, A.; Graham, H.; Thomas, J.J.C.; Chalkley, A.E.; Daley, A.J. Effectiveness of physical activity interventions delivered or prompted by health professionals in primary care settings: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2022, 376, e068465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.T.; Barcelos, A.M.; Mills, D.S. Links between pet ownership and exercise on the mental health of veterinary professionals. Vet. Rec. 2023, 10, e62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, R.C.; Barker, P.R.; Colpe, L.J.; Epstein, J.F.; Gfroerer, J.C.; Hiripi, E.; Howes, M.J.; Normand, S.-L.T.; Manderscheid, R.W.; Walters, E.E.; et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2003, 60, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyrbye, L.N.; Szydlo, D.W.; Downing, S.M.; Sloan, J.A.; Shanafelt, T.D. Development and preliminary psychometric properties of a well-being index for medical students. BMC Med. Educ. 2010, 10, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVellis, R.F. Scale Development: Theory and Applications, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-1-5063-4156-9. [Google Scholar]

- Bruzeguini, M.V.; Corassa, R.B.; Wang, Y.-P.; Andrade, L.H.; Sarti, T.D.; Viana, M.C. The performance of K6 as a screening tool for mood disorders: A population-based study of the São Paulo metropolitan area. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2024, 18, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mocanu, E.; Mohr, C.; Pouyan, N.; Thuillard, S.; Dan-Glauser, E.S. Reasons, years and frequency of yoga practice: Effect on emotion response reactivity. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gohel, M.K.; Phatak, A.G.; Kharod, U.N.; Pandya, B.A.; Prajapati, B.L.; Shah, U.M. Effect of long-term regular yoga on physical health of yoga practitioners. Indian J. Community Med. 2021, 46, 508–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brscic, M.; Contiero, B.; Schianchi, A.; Marogna, C. Challenging suicide, burnout, and depression among veterinary practitioners and students: Text mining and topics modelling analysis of the scientific literature. BMC Vet. Res. 2021, 17, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andela, M. Burnout, somatic complaints, and suicidal ideations among veterinarians: Development and validation of the veterinarians stressors inventory. J. Vet. Behav. 2020, 37, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foote, A. Burnout, compassion fatigue and moral distress in veterinary professionals. Vet. Nurse 2023, 14, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spendelow, J.; Cripwell, C.; Stott, R.; Francis, K.; Powell, J.; Cavanagh, K.; Corbett, R. Workplace stressor factors, profiles and the relationship to career stage in UK veterinarians, veterinary nurses and students. Vet. Med. Sci. 2024, 10, e1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vivian, S.R.; Holt, S.L.; Williams, J. What factors influence the perceptions of job satisfaction in registered veterinary nurses currently working in veterinary practice in the United Kingdom? J. Vet. Med. Educ. 2022, 49, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbe Montoya, A.I.; Hazel, S.J.; Matthew, S.M.; McArthur, M.L. Why do veterinarians leave clinical practice? A qualitative study using thematic analysis. Vet. Rec. 2021, 188, e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilton, K.; Burke, K.; Signal, T. Mental health in the veterinary profession: An individual or organisational focus? Aust. Vet. J. 2023, 101, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podpečan, O.; Hlebec, V.; Kuhar, M.; Kubale, V.; Jakovac Strajn, B. Predictors of Burnout and Well-Being Among Veterinarians in Slovenia. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudry, A.; Truchot, D.; Andela, M. Development and longitudinal validation of the Veterinary Stressors Questionnaire. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 21846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, C.E.; Norris, K.; Dawkins, S.; Martin, A. Barriers to mental health help-seeking in veterinary professionals working in Australia and New Zealand: A preliminary cross-sectional analysis. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 1051571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M.; Hagen, B.N.M.; Gohar, B.; Wichtel, J.; Jones-Bitton, A. A qualitative study exploring the perceived effects of veterinarians’ mental health on provision of care. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1064932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, T.A.F.; Alqurashi, A.A.B.; Mahmud, I.; Alharbi, R.J.; Islam, S.M.S.; Almustanyir, S.; Maklad, A.E.; AlSarraj, A.; Mughaiss, L.N.; Al-Tawfiq, J.A.; et al. COVID-19: Factors Associated with the Psychological Distress, Fear and Resilient Coping Strategies among Community Members in Saudi Arabia. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Montero, E.; Ferradás, M.d.M.; Freire, C. Personal Resources for Psychological Well-Being in University Students: The Roles of Psychological Capital and Coping Strategies. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2024, 14, 2686–2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emikpe, B.O.; Asare, D.A.; Emikpe, A.O.; Botchway, L.A.N.; Bonney, R.A. Prevalence and associated risk factors of burnout amongst veterinary students in Ghana. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0271434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moir, F.; Van den Brink, A. Current insights in veterinarians’ psychological wellbeing. N. Z. Vet. J. 2020, 68, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mincarone, P.; Bodini, A.; Tumolo, M.R.; Sabina, S.; Colella, R.; Mannini, L.; Sabato, E.; Leo, C.G. Association Between Physical Activity and the Risk of Burnout in Health Care Workers: Systematic Review. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2024, 10, e49772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Olds, T.; Curtis, R.; Dumuid, D.; Virgara, R.; Watson, A.; Szeto, K.; O’Connor, E.; Ferguson, T.; Eglitis, E.; et al. Effectiveness of physical activity interventions for improving depression, anxiety and distress: An overview of systematic reviews. Br. J. Sports Med. 2023, 57, 1203–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | n | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Professional profile | ||

| Monthly income (USD) a | ||

| Up to 640 | 722 | 36.2% |

| 641–1165 | 539 | 27.1% |

| 1166–2330 | 354 | 17.8% |

| 2331+ | 168 | 8.4% |

| I prefer not to answer | 209 | 10.5% |

| Current position | ||

| Employee at a veterinary clinic | 739 | 37.1% |

| Owner or co-owner | 558 | 28.0% |

| Surrogate veterinary | 252 | 12.7% |

| Academic position (professor, researcher, etc.) | 157 | 7.9% |

| Non-executive role in the industry | 100 | 5.0% |

| Consultant | 93 | 4.7% |

| Other | 93 | 4.7% |

| Time from graduation (years) | ||

| 0–5 | 748 | 37.6% |

| 6–10 | 403 | 20.2% |

| 11–20 | 515 | 25.9% |

| 21+ | 326 | 16.4% |

| Work conditions | ||

| Current workload | ||

| I’m working more hours than I would like to | 1000 | 50.2% |

| I’m working less hours than I would like to | 259 | 13.0% |

| I’m satisfied with the number of hours I’m working | 637 | 32.0% |

| I prefer not to answer | 96 | 4.8% |

| In addition to your regular job, do you have a second job? | ||

| Yes | 772 | 38.8% |

| No | 1172 | 58.8% |

| I prefer not to answer | 48 | 2.4% |

| Career satisfaction | ||

| Would you recommend a veterinary career? | ||

| Yes | 774 | 38.9% |

| No | 1126 | 56.5% |

| I prefer not to answer | 92 | 4.6% |

| Do you regret becoming a veterinarian? | ||

| Yes | 542 | 27.2% |

| No | 1368 | 68.7% |

| I prefer not to answer | 82 | 4.1% |

| Predictors | Psychological Distress (K6) | Well-Being (PWBI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | |

| Sociodemographic factors | ||||

| Age | 1.00 (0.98–1.03) | 0.747 | 1.03 (1.01–1.05) | 0.025 |

| Gender (ref: Female) | 1.25 (0.94–1.65) | 0.103 | 0.48 (0.37–0.62) | <0.001 |

| Marital status (ref: Single) | ||||

| Married | 0.74 (0.59–0.94) | 0.013 | 1.13 (0.88–1.52) | 0.285 |

| Separated | 1.46 (0.92–2.33) | 0.103 | 0.86 (1.16–3.26) | 0.011 |

| Widower | 1.03 (0.20–5.22) | 0.979 | 3.22 (0.31–5.21) | 0.738 |

| Parental status (ref: No children) | 1.04 (0.81–1.33) | 0.755 | 0.90 (0.69–1.16) | 0.404 |

| Occupational factors | ||||

| Income | 0.85 (0.75–0.98) | 0.022 | 1.09 | 0.223 |

| Time since graduation | 0.98 (0.95–0.99) | 0.038 | 1.02 (1.00–1.05) | 0.053 |

| Workload satisfaction (ref: Satisfied) | ||||

| Less than desired | 1.26 (0.92–1.73) | 0.148 | 0.80 (0.59–1.10) | 0.174 |

| More than desired | 1.74 (1.37–2.21) | <0.001 | 0.31 (0.24–0.40) | <0.001 |

| Second job (ref: No) | 0.98 (0.80–1.21) | 0.878 | 1.30 (1.03–1.64) | 0.030 |

| Career satisfaction | ||||

| Recommend career (ref: Yes) | 1.84 (1.44–2.35) | <0.001 | 0.42 (0.32–0.53) | <0.001 |

| Regret career (ref: No) | 2.53 (2.00–3.20) | <0.001 | 0.54 (0.39–0.74) | <0.001 |

| Model fit indices | ||||

| K6: χ2 = 302.97, p < 0.001; Nagelkerke R2 = 0.196; Hosmer–Lemeshow test p = 0.962 | ||||

| PWBI: χ2 = 468.21, p < 0.001; Nagelkerke R2 = 0.300; Hosmer–Lemeshow test p = 0.386 | ||||

| Coping Strategies | Psychological Distress (K6) | Well-Being (PWBI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | |

| Physical exercise | 0.92 (0.83–1.02) | 0.119 | 1.06 (0.95–1.19) | 0.281 |

| Yoga practice | 1.20 (0.99–1.45) | 0.061 | 0.79 (0.66–0.94) | 0.010 |

| Socialize with friends | 0.82 (0.71–0.95) | 0.006 | 1.26 (1.08–1.47) | 0.003 |

| Meditate | 0.89 (0.77–1.03) | 0.119 | 1.11 (0.97–1.26) | 0.130 |

| Read for pleasure | 0.94 (0.84–1.06) | 0.315 | 1.17 (1.04–1.31) | 0.009 |

| Travel for pleasure | 0.67 (0.58–0.78) | <0.001 | 1.36 (1.17–1.57) | <0.001 |

| Volunteer | 0.86 (0.76–0.97) | 0.013 | 1.07 (0.95–1.21) | 0.241 |

| Spend time on a hobby | 0.81 (0.71–0.92) | <0.001 | 1.23 (1.08–1.41) | 0.002 |

| Spend time with family | 0.69 (0.60–0.80) | <0.001 | 1.83 (1.54–2.18) | <0.001 |

| Sleep at least 8 h a night | 0.80 (0.72–0.89) | <0.001 | 1.36 (1.21–1.53) | <0.001 |

| Model fit indices | ||||

| K6: χ2 = 334.35, p < 0.001; Nagelkerke R2 = 0.215; Hosmer–Lemeshow test p = 0.383 | ||||

| PWBI: χ2 = 366.20, p < 0.001; Nagelkerke R2 = 0.241; Hosmer–Lemeshow test p = 0.282 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gresele, B.S.; Pereira, J.L.; Rosa, A.d.S.; Lyrio-Carvalho, H.C.; Ulisses, S.M.V.; da Silva, A.R.S. Risk Factors and Protection Associated with Well-Being and Psychological Distress of Veterinarians in Brazil. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 835. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci12090835

Gresele BS, Pereira JL, Rosa AdS, Lyrio-Carvalho HC, Ulisses SMV, da Silva ARS. Risk Factors and Protection Associated with Well-Being and Psychological Distress of Veterinarians in Brazil. Veterinary Sciences. 2025; 12(9):835. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci12090835

Chicago/Turabian StyleGresele, Bianca S., Jefferson L. Pereira, Anderson da S. Rosa, Helena C. Lyrio-Carvalho, Sofia M. V. Ulisses, and Alexandre R. S. da Silva. 2025. "Risk Factors and Protection Associated with Well-Being and Psychological Distress of Veterinarians in Brazil" Veterinary Sciences 12, no. 9: 835. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci12090835

APA StyleGresele, B. S., Pereira, J. L., Rosa, A. d. S., Lyrio-Carvalho, H. C., Ulisses, S. M. V., & da Silva, A. R. S. (2025). Risk Factors and Protection Associated with Well-Being and Psychological Distress of Veterinarians in Brazil. Veterinary Sciences, 12(9), 835. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci12090835