Precision Glyco-Modulation of Macrophages with EF-M2 (ImmutalonTM) Improves Function and Lowers Inflammatory Biomarkers in Aging Dogs: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Oversight

2.2. Participants

2.3. Randomization and Masking

2.4. Interventions

2.5. Outcomes

2.6. Assessments and Quality Control

2.7. Sample-Size Calculation

2.8. Statistical Analysis

- Co-primary endpoints: For P1 and P2, an ANCOVA model of change from baseline was fitted with treatment group as a fixed effect and the corresponding baseline value as a covariate; additional fixed effects for center/strata could be included as prespecified sensitivity terms. The hierarchical gatekeeping sequence required statistical significance on P1 before formal testing of P2.

- Key secondary endpoints: Continuous endpoints (e.g., week-4 activity, BAER, TEWL) were analyzed via ANCOVA on change from baseline with baseline as covariate. Family-wise error was controlled across key secondaries using Holm–Bonferroni procedures; BAER was a prioritized secondary endpoint. Symptom endpoints (PVAS, OTIS-3) were restricted to dogs symptomatic at baseline per protocol.

- Responder endpoints: PGIC responder analyses used prespecified cut points; between-group comparisons used Fisher’s exact test with 95% CIs for risk differences.

- Pharmacodynamic endpoints: Δ(day 7–day 0) changes were compared between groups using ANCOVA, adjusting for baseline; exploratory correlations of ΔPD with clinical changes and mediation analyses were prespecified in the SAP.

- Missing data: Primary analyses assumed missing at random (MAR) and used ANCOVA/MMRM as appropriate; sensitivity analyses used multiple imputation (MICE) and PP populations.

2.9. Data Monitoring and Quality Assurance

2.10. Ethics and Informed Consent

2.11. Role of the Funding Source

3. Results

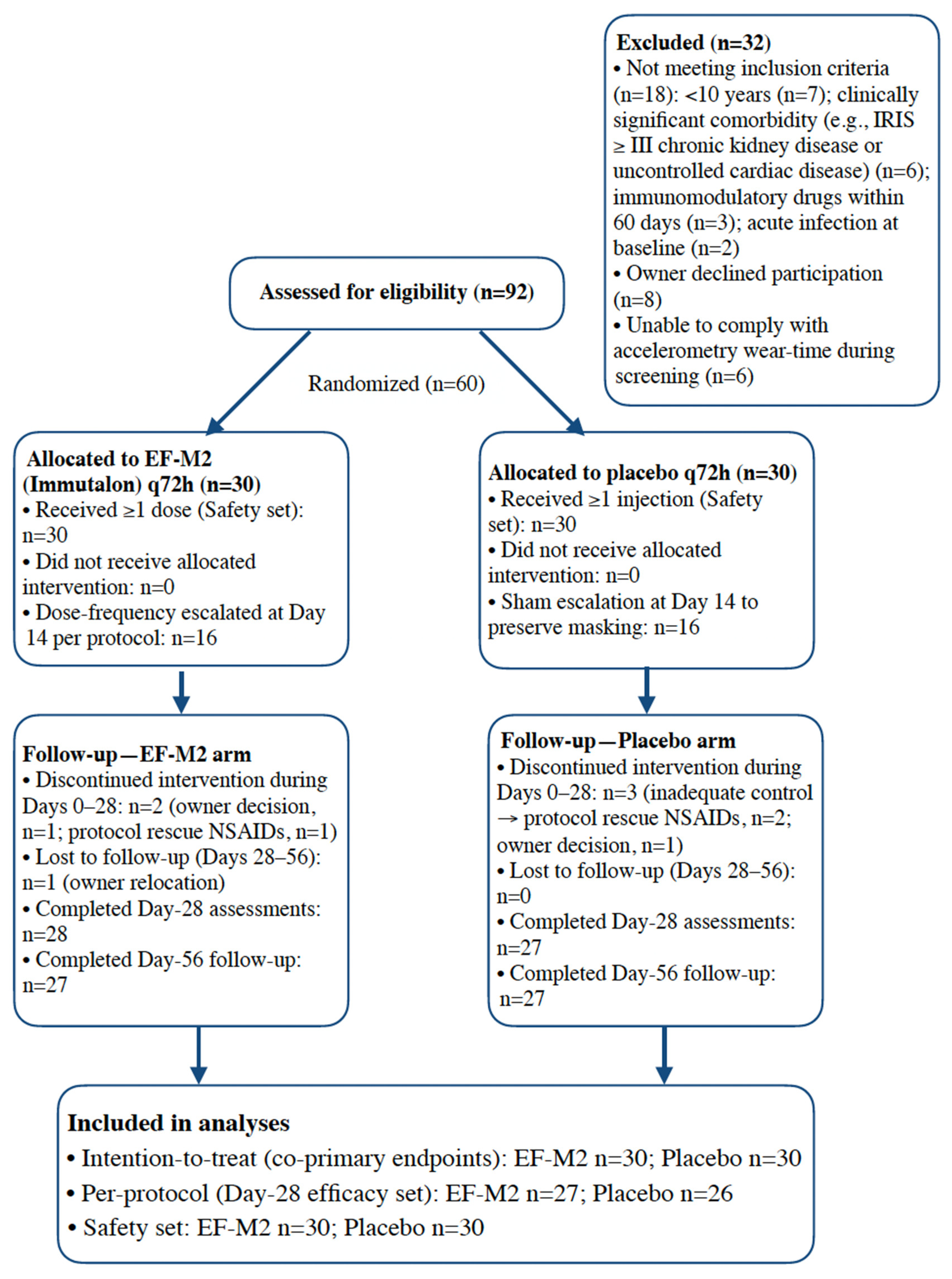

3.1. Participants and Follow-Up

3.2. Baseline Characteristics

3.3. Co-Primary Endpoints

3.4. Key Secondary Endpoints

3.5. Global Impression of Change

3.6. Pharmacodynamic Biomarkers

3.7. Safety

3.8. Data Completeness and Protocol Adherence

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fulop, T.; Larbi, A.; Pawelec, G.; Khalil, A.; Cohen, A.A.; Hirokawa, K.; Witkowski, J.M.; Franceschi, C. Immunology of Aging: The Birth of Inflammaging. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2023, 64, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- De Maeyer, R.P.H.; Chambers, E.S. The impact of ageing on monocytes and macrophages. Immunol. Lett. 2021, 230, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linehan, E.; Fitzgerald, D.C. Ageing and the immune system: Focus on macrophages. Eur. J. Microbiol. Immunol. 2015, 5, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- McCusker, R.H.; Kelley, K.W. Immune-neural connections: How the immune system’s response to infectious agents influences behavior. J. Exp. Biol. 2013, 216 Pt 1, 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chen, O.; Luo, X.; Ji, R.R. Macrophages and microglia in inflammation and neuroinflammation underlying different pain states. Med. Rev. 2023, 3, 381–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chen, S.; Saeed, A.F.U.H.; Liu, Q.; Jiang, Q.; Xu, H.; Xiao, G.G.; Rao, L.; Duo, Y. Macrophages in immunoregulation and therapeutics. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nguyen, T.Q.T.; Cho, K.A. Targeting immunosenescence and inflammaging: Advancing longevity research. Exp. Mol. Med. 2025, 57, 1881–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zaal, A.; Li, R.J.E.; Lübbers, J.; Bruijns, S.C.M.; Kalay, H.; van Kooyk, Y.; van Vliet, S.J. Activation of the C-Type Lectin MGL by Terminal GalNAc Ligands Reduces the Glycolytic Activity of Human Dendritic Cells. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- van Vliet, S.J.; van Liempt, E.; Saeland, E.; Aarnoudse, C.A.; Appelmelk, B.; Irimura, T.; Geijtenbeek, T.B.; Blixt, O.; Alvarez, R.; van Die, I.; et al. Carbohydrate profiling reveals a distinctive role for the C-type lectin MGL in the recognition of helminth parasites and tumor antigens by dendritic cells. Int. Immunol. 2005, 17, 661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcelo, F.; Supekar, N.; Corzana, F.; van der Horst, J.C.; Vuist, I.M.; Live, D.; Boons, G.P.H.; Smith, D.F.; van Vliet, S.J. Identification of a secondary binding site in human macrophage galactose-type lectin by microarray studies: Implications for the molecular recognition of its ligands. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 1300–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gabba, A.; Bogucka, A.; Luz, J.G.; Diniz, A.; Coelho, H.; Corzana, F.; Cañada, F.J.; Marcelo, F.; Murphy, P.V.; Birrane, G. Crystal Structure of the Carbohydrate Recognition Domain of the Human Macrophage Galactose C-Type Lectin Bound to GalNAc and the Tumor-Associated Tn Antigen. Biochemistry 2021, 60, 1327–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehder, D.S.; Nelson, R.W.; Borges, C.R. Glycosylation status of vitamin D binding protein in cancer patients. Protein Sci. 2009, 18, 2036–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nabeshima, Y.; Abe, C.; Kawauchi, T.; Hiroi, T.; Uto, Y.; Nabeshima, Y.I. Simple method for large-scale production of macrophage activating factor GcMAF. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 19122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Borges, C.R.; Rehder, D.S. Glycan structure of Gc Protein-derived Macrophage Activating Factor as revealed by mass spectrometry. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2016, 606, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pokushalov, E.; Kudlay, D.; Revkov, N.; Shcherbakova, A.; Johnson, M.; Miller, R. Targeted Macrophage Modulation as a Disease-Modifying Approach in Canine Osteoarthritis: The Efficacy of EF-M2 (Immutalon) in a Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Study. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Strizova, Z.; Benesova, I.; Bartolini, R.; Novysedlak, R.; Cecrdlova, E.; Foley, L.K.; Striz, I. M1/M2 macrophages and their overlaps-myth or reality? Clin. Sci. 2023, 137, 1067–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Brown, D.C.; Boston, R.C.; Coyne, J.C.; Farrar, J.T. Ability of the canine brief pain inventory to detect response to treatment in dogs with osteoarthritis. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2008, 233, 1278–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Davies, V.; Reid, J.; Wiseman-Orr, M.L.; Scott, E.M. Optimising outputs from a validated online instrument to measure health-related quality of life (HRQL) in dogs. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0221869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wiseman-Orr, M.L.; Scott, E.M.; Reid, J.; Nolan, A.M. Validation of a structured questionnaire as an instrument to measure chronic pain in dogs on the basis of effects on health-related quality of life. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2006, 67, 1826–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yam, P.S.; Penpraze, V.; Young, D.; Todd, M.S.; Cloney, A.D.; Houston-Callaghan, K.A.; Reilly, J.J. Validity, practical utility and reliability of Actigraph accelerometry for the measurement of habitual physical activity in dogs. J. Small Anim. Pract. 2011, 52, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szczykutowicz, J. Ligand Recognition by the Macrophage Galactose-Type C-Type Lectin: Self or Non-Self?—A Way to Trick the Host’s Immune System. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 17078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ravnsborg, T.; Olsen, D.T.; Thysen, A.H.; Christiansen, M.; Houen, G.; Højrup, P. The glycosylation and characterization of the candidate Gc macrophage activating factor. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2010, 1804, 909–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirikovich, S.S.; Levites, E.V.; Proskurina, A.S.; Ritter, G.S.; Peltek, S.E.; Vasilieva, A.R.; Ruzanova, V.S.; Dolgova, E.V.; Oshihmina, S.G.; Sysoev, A.V.; et al. The Molecular Aspects of Functional Activity of Macrophage-Activating Factor GcMAF. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 17396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Brown, D.C.; Boston, R.C.; Coyne, J.C.; Farrar, J.T. Development and psychometric testing of an instrument designed to measure chronic pain in dogs with osteoarthritis. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2007, 68, 631–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hilborn, E.C.; Rudinsky, A.J.; Kieves, N.R. Commercially available wearable health monitors in dogs only had a very strong correlation during longer durations of time: A pilot study. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2024, 85, ajvr.24.06.0162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanger, A.; Buhmann, G.; Dörfelt, S.; Zablotski, Y.; Fischer, A. Rapid hearing threshold assessment with modified auditory brainstem response protocols in dogs. Front. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 1358410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kurashina, R.; Denda-Nagai, K.; Saba, K.; Hisai, T.; Hara, H.; Irimura, T. Intestinal lamina propria macrophages upregulate interleukin-10 mRNA in response to signals from commensal bacteria recognized by MGL1/CD301a. Glycobiology 2021, 31, 827–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sancho, D.; Reis e Sousa, C. Signaling by myeloid C-type lectin receptors in immunity and homeostasis. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2012, 30, 491–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Szanto, A.; Balint, B.L.; Nagy, Z.S.; Barta, E.; Dezso, B.; Pap, A.; Szeles, L.; Poliska, S.; Oros, M.; Evans, R.M.; et al. STAT6 transcription factor is a facilitator of the nuclear receptor PPARγ-regulated gene expression in macrophages and dendritic cells. Immunity 2010, 33, 699–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yoon, Y.S.; Kim, S.Y.; Kim, M.J.; Lim, J.H.; Cho, M.S.; Kang, J.L. PPARγ activation following apoptotic cell instillation promotes resolution of lung inflammation and fibrosis via regulation of efferocytosis and proresolving cytokines. Mucosal Immunol. 2015, 8, 1031–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yin, C.; Heit, B. Cellular Responses to the Efferocytosis of Apoptotic Cells. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 631714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Celik, M.Ö.; Labuz, D.; Keye, J.; Glauben, R.; Machelska, H. IL-4 induces M2 macrophages to produce sustained analgesia via opioids. JCI Insight 2020, 5, e133093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Heger, L.; Balk, S.; Lühr, J.J.; Heidkamp, G.F.; Lehmann, C.H.K.; Hatscher, L.; Purbojo, A.; Hartmann, A.; Garcia-Martin, F.; Nishimura, S.I.; et al. CLEC10A Is a Specific Marker for Human CD1c+ Dendritic Cells and Enhances Their Toll-Like Receptor 7/8-Induced Cytokine Secretion. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pye, C.; Bruniges, N.; Peffers, M.; Comerford, E. Advances in the pharmaceutical treatment options for canine osteoarthritis. J. Small Anim. Pract. 2022, 63, 721–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- FDA Center for Veterinary Medicine. Get the Facts About Pain Relievers for Pets; U.S. Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/animal-veterinary/animal-health-literacy/get-facts-about-pain-relievers-pets (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Homedes, J.; Ocak, M.; Riedle, S.; Salichs, M. A blinded, randomized and controlled multicenter field study investigating the safety and efficacy of long-term use of enflicoxib in the treatment of naturally occurring osteoarthritis in client-owned dogs. Front. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 1349901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kaeberlein, M.; Creevy, K.E.; Promislow, D.E. The dog aging project: Translational geroscience in companion animals. Mamm. Genome 2016, 27, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hoffman, J.M.; Creevy, K.E.; Franks, A.; O’Neill, D.G.; Promislow, D.E.L. The companion dog as a model for human aging and mortality. Aging Cell 2018, 17, e12737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Creevy, K.E.; Akey, J.M.; Kaeberlein, M.; Promislow, D.E.L. Dog Aging Project Consortium. An open science study of ageing in companion dogs. Nature 2022, 602, 51–57, Erratum in Nature 2022, 608, E33. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-05179-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Variable | Placebo (n = 30) | EF-M2 (n = 30) | Total (n = 60) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 12.3 (1.7) | 12.6 (1.9) | 12.4 (1.8) | 0.48 |

| Weight, kg | 17.3 (10.3) | 18.6 (11.7) | 17.9 (11.0) | 0.65 |

| Active minutes/day at baseline | 147.5 (43.9) | 142.2 (32.2) | 144.8 (38.3) | 0.60 |

| CBPI-PSS (0–10) | 3.84 (2.52) | 4.68 (2.03) | 4.26 (2.31) | 0.16 |

| HRQL-vitality (0–10) | 3.79 (1.40) | 3.98 (1.06) | 3.88 (1.23) | 0.56 |

| Appetite VAS (0–10) | 6.62 (1.54) | 6.50 (1.41) | 6.56 (1.47) | 0.74 |

| Male sex—n (%) | 17 (56.7%) | 15 (50.0%) | 32 (53.3%) | 0.80 |

| Intact—n (%) | 12 (40.0%) | 15 (50.0%) | 27 (45.0%) | 0.60 |

| Pain at baseline—n (%) | 20 (66.7%) | 16 (53.3%) | 36 (60.0%) | 0.19 |

| Pruritus at baseline—n (%) | 11 (36.7%) | 8 (26.7%) | 19 (31.7%) | 0.58 |

| Otitis at baseline—n (%) | 4 (13.3%) | 7 (23.3%) | 11 (18.3%) | 0.50 |

| Endpoint (Change from Baseline) | Placebo (n = 30) | EF-M2 (n = 30) | Adjusted Difference (EF-M2 − Placebo), 95% CI | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1: Objective activity (week 1 vs. Baseline), min/day—Δ mean (SD) | 6.8 (9.4) | 30.0 (9.8) | 23.05 (18.16 to 27.94) | <0.001 |

| P2: Vitality composite z (day 28 vs. Day 0)—Δ mean (SD) | 0.70 (0.71) | 2.71 (1.15) | 2.01 (1.52 to 2.50) | <0.001 |

| Endpoint (Change from Baseline) | Placebo | EF-M2 | Adjusted Difference (EF-M2 − Placebo), 95% CI | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Objective activity (week 4 vs. Baseline), min/day—Δ mean (SD) | 9.9 (12.3) | 43.0 (11.9) | 33.00 (26.83 to 39.18) | <0.001 |

| BAER threshold (dB), day 28 − day 0—Δ mean (SD) | −0.92 (5.53) | −4.78 (5.22) | −5.28 (−7.53 to −3.04) | <0.001 |

| TEWL (g/m2·h), day 28 − day 0—Δ mean (SD) | −1.83 (2.75) | −3.57 (3.52) | −1.35 (−2.45 to −0.25) | 0.02 |

| PVAS (0–10), day 28 − day 0—Δ mean (SD) [symptomatic at baseline] * | −0.85 (1.04) | −2.96 (1.28) | −2.05 (−3.07 to −1.04) | 0.001 |

| OTIS-3 (0–10), day 28 − day 0—Δ mean (SD) [symptomatic at baseline] † | −3.00 (2.16) | −3.71 (1.89) | −0.64 (−3.22 to 1.95) | 0.64 |

| Outcome | Placebo | EF-M2 | Risk Difference (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PGIC responder (day 28)—n/N (%) | 3/30 (10.0%) | 28/30 (93.3%) | 0.83 (0.69 to 0.97) | <0.001 |

| PGIC responder (day 56, off-drug)—n/N (%) | 5/30 (16.7%) | 15/30 (50.0%) | 0.33 (0.11 to 0.56) | 0.01 |

| Biomarker—Δ Mean (SD) | Placebo | EF-M2 | Adjusted Difference (EF-M2 − Placebo), 95% CI | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARG1:iNOS ratio | 0.070 (0.055) | 0.264 (0.078) | 0.196 (0.162 to 0.230) | <0.001 |

| IL-10, pg/mL | 1.40 (0.97) | 4.26 (1.73) | 2.85 (2.13 to 3.57) | <0.001 |

| TNF-α, pg/mL | −0.27 (0.48) | −1.40 (0.72) | −1.12 (−1.44 to −0.81) | <0.001 |

| hs-CRP, mg/L | −0.15 (0.36) | −0.85 (0.57) | −0.71 (−0.95 to −0.46) | <0.001 |

| IL-6, pg/mL | −0.07 (0.22) | −0.51 (0.25) | −0.44 (−0.56 to −0.32) | <0.001 |

| Safety Outcome | Placebo (n = 30) | EF-M2 (n = 30) |

|---|---|---|

| Subjects with ≥1 adverse event—n (%) | 6 (20.0%) | 5 (16.7%) |

| Total adverse events—n | 6 | 5 |

| Grade ≥ 2 AEs—n | 1 | 1 |

| Serious AEs—n | 0 | 0 |

| Injection site erythema—n (%) | 3 (10.0%) | 1 (3.3%) |

| Mild lethargy ≤ 24 h—n (%) | 2 (6.7%) | 2 (6.7%) |

| Transient low-grade fever—n (%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (3.3%) |

| ALT/AST increased—n (%) | 1 (3.3%) | 1 (3.3%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pokushalov, E.; Kudlay, D.; Garcia, C.; Smith, J.; Revkov, N.; Shcherbakova, A.; Miller, R. Precision Glyco-Modulation of Macrophages with EF-M2 (ImmutalonTM) Improves Function and Lowers Inflammatory Biomarkers in Aging Dogs: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 1168. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci12121168

Pokushalov E, Kudlay D, Garcia C, Smith J, Revkov N, Shcherbakova A, Miller R. Precision Glyco-Modulation of Macrophages with EF-M2 (ImmutalonTM) Improves Function and Lowers Inflammatory Biomarkers in Aging Dogs: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Veterinary Sciences. 2025; 12(12):1168. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci12121168

Chicago/Turabian StylePokushalov, Evgeny, Dmitry Kudlay, Claire Garcia, John Smith, Nikolai Revkov, Anastasya Shcherbakova, and Richard Miller. 2025. "Precision Glyco-Modulation of Macrophages with EF-M2 (ImmutalonTM) Improves Function and Lowers Inflammatory Biomarkers in Aging Dogs: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial" Veterinary Sciences 12, no. 12: 1168. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci12121168

APA StylePokushalov, E., Kudlay, D., Garcia, C., Smith, J., Revkov, N., Shcherbakova, A., & Miller, R. (2025). Precision Glyco-Modulation of Macrophages with EF-M2 (ImmutalonTM) Improves Function and Lowers Inflammatory Biomarkers in Aging Dogs: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Veterinary Sciences, 12(12), 1168. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci12121168