A Small-Molecular-Weight Bacteriocin-like Inhibitory Substance (BLIS) UI-11 Produced by Lactobacillus plantarum HYH-11 as an Antimicrobial Agent for Aeromonas hydrophila

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Isolation and Identification of Bacteria

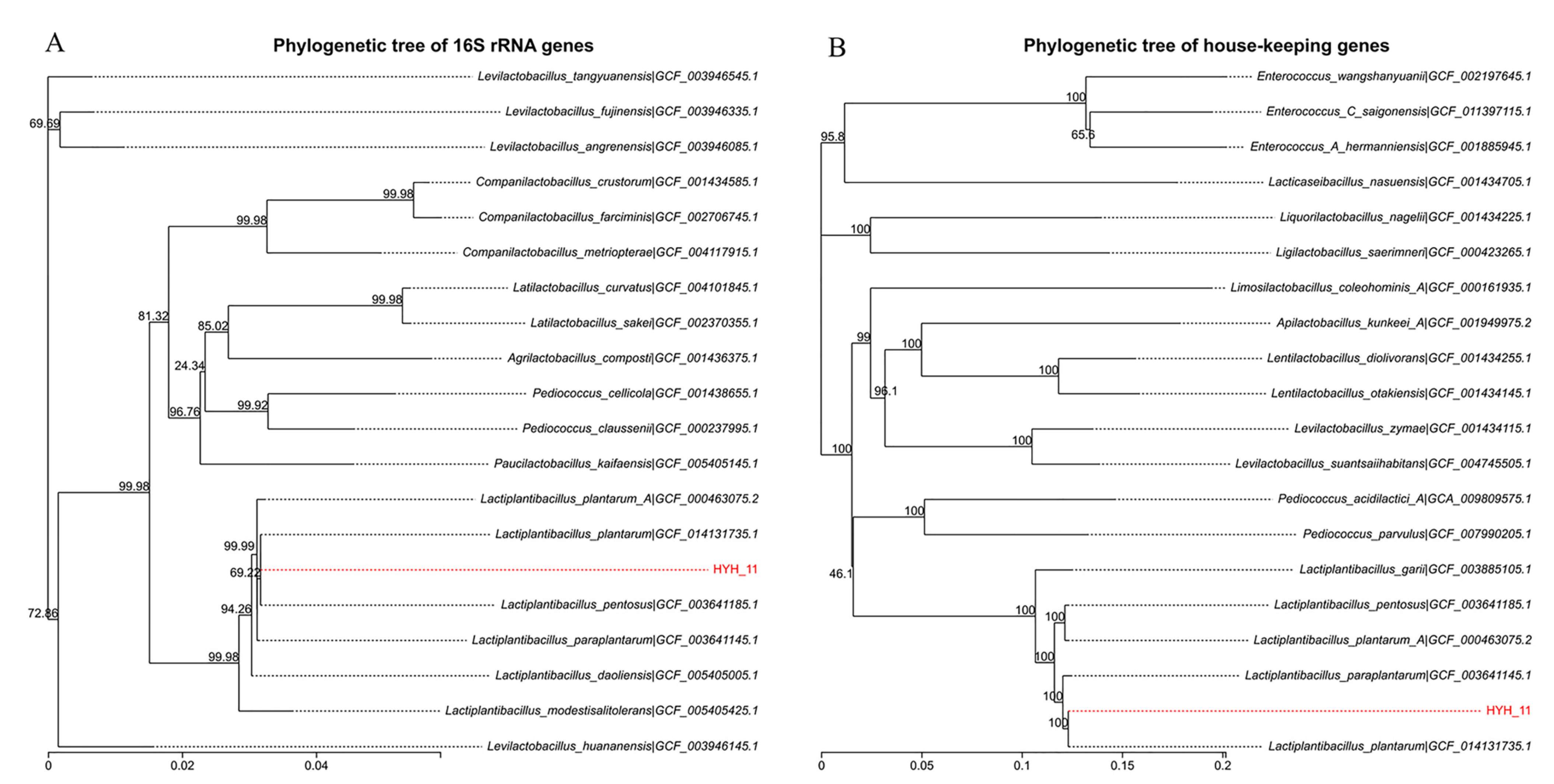

2.2. Evolutionary Tree of L. plantarum HYH-11

2.3. Preparation of L. plantarum CFS

2.4. Basic Antimicrobial Activity Assay for CFS

2.5. Antimicrobial Spectrum

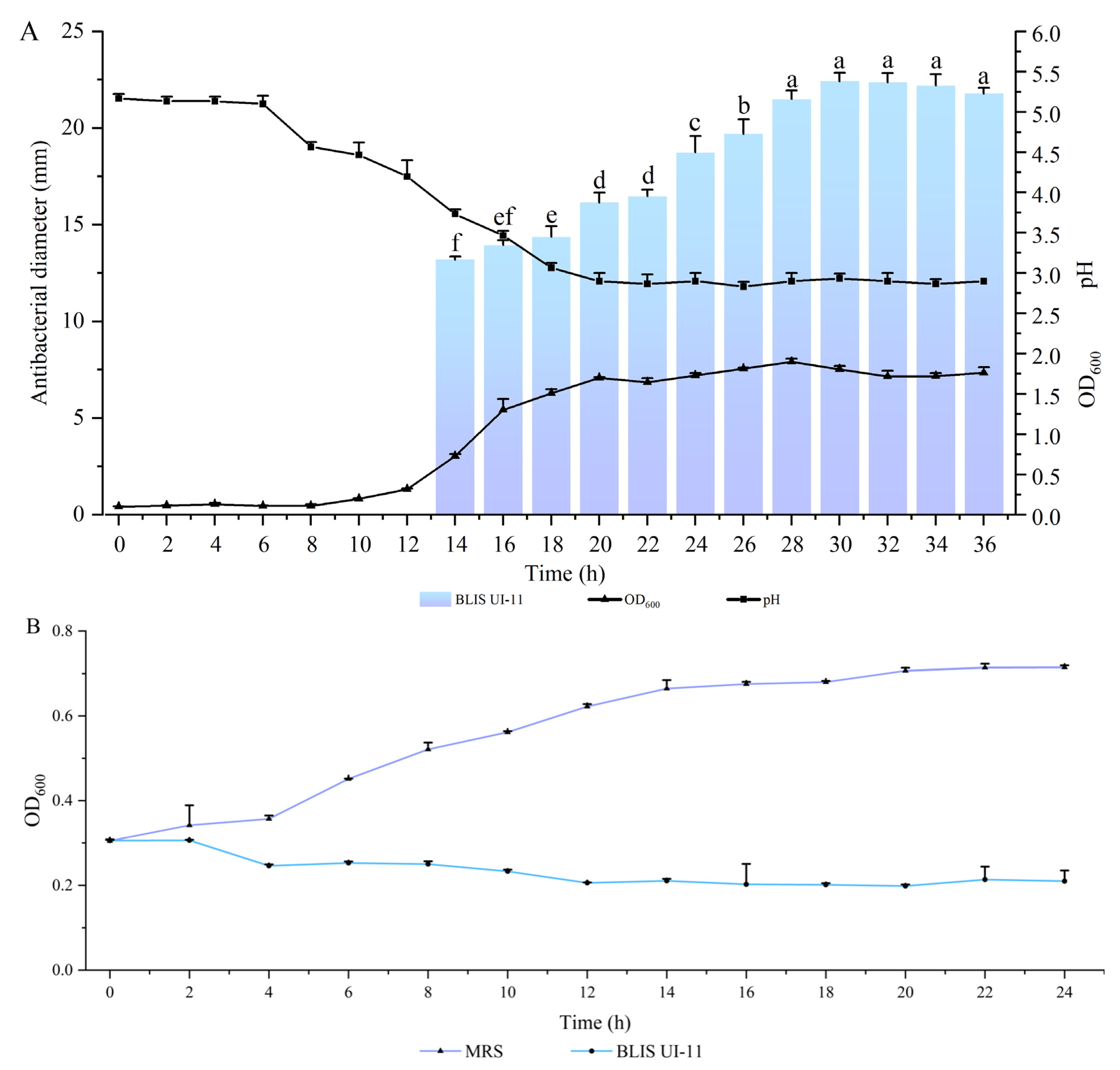

2.6. BLIS UI-11 Production Kinetics

2.7. Bactericidal Curve of A. hydrophila ATCC 7966 Under BLIS UI-11

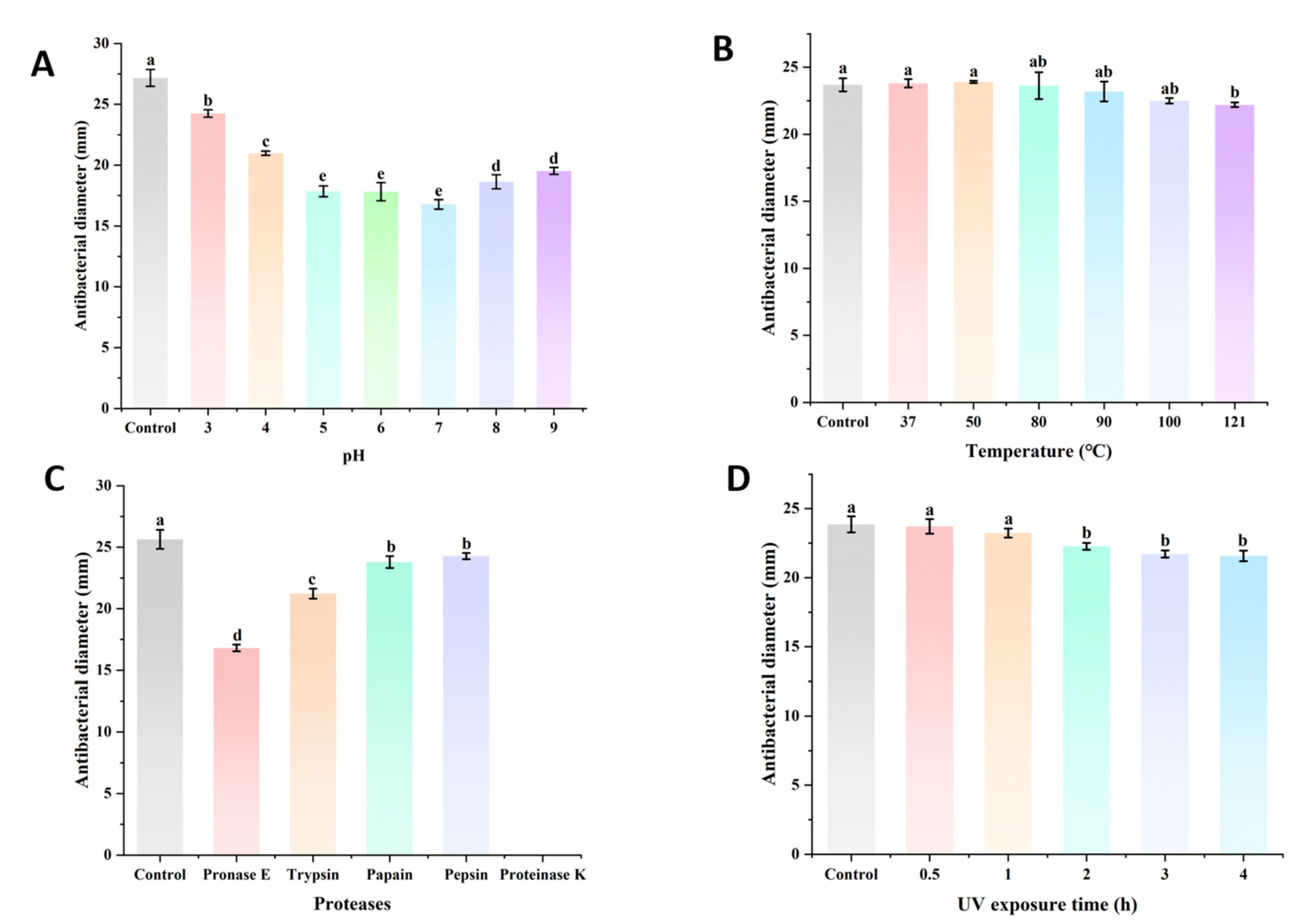

2.8. The Stability Assay of BLIS UI-11

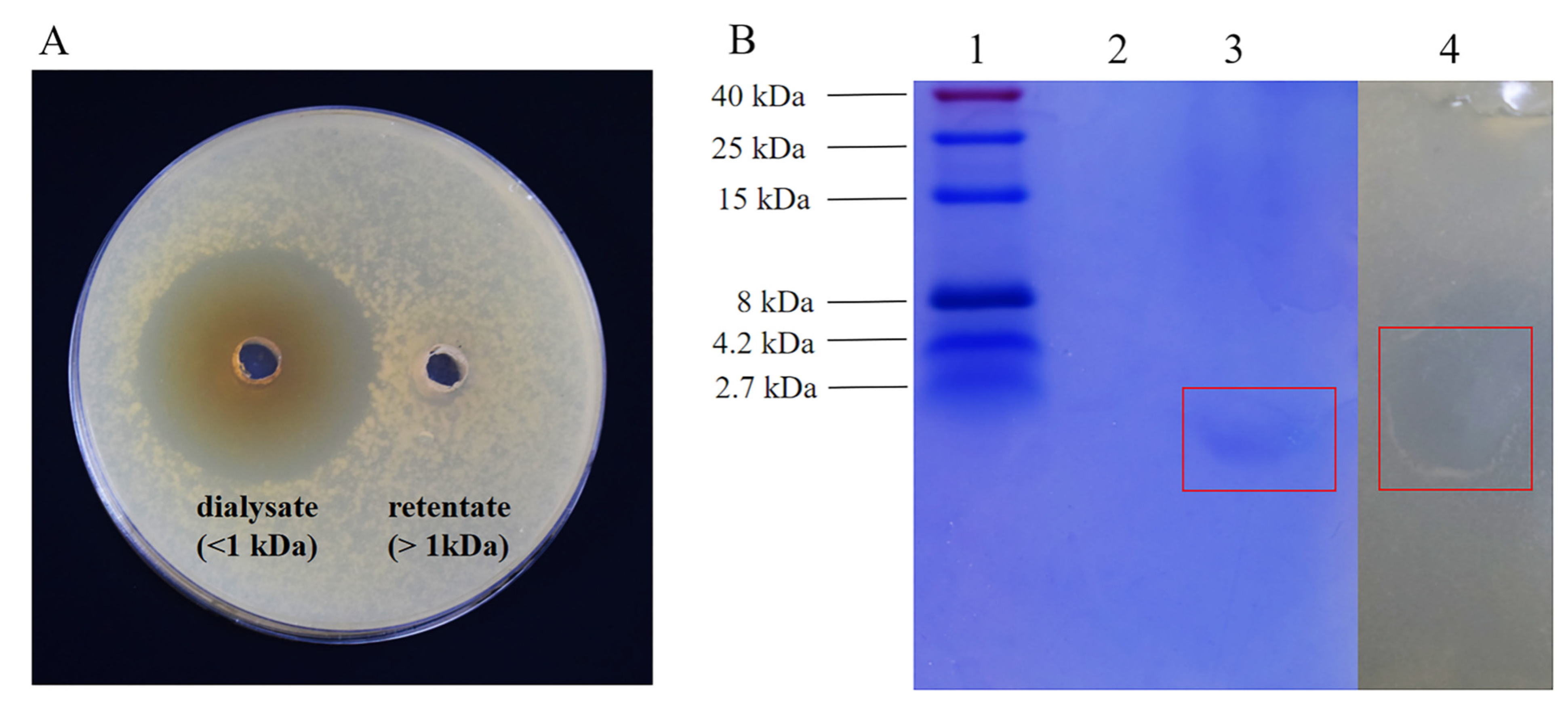

2.9. Molecular Weight Determination of BLIS UI-11 and Original Activity Assay

2.10. Whole Genome Analysis of L. plantarum HYH-11

2.11. Live/Dead Cell Staining Experiment

2.12. Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM)

2.13. The Security Testing of BLIS UI-11

2.14. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Evolutionary Tree of HYH-11

3.2. The Antibacterial Activity and Antibacterial Spectrum

3.3. The Production Kinetics Curve of L. plantarum HYH-11 and the Inhibition Curve of A. hydrophila ATCC 7966 Under the Action of BLIS UI-11

3.4. Effect of pH, Temperature, Protease and UV on the Antimicrobial Activity

3.5. The Analysis of Molecular Weight Size

3.6. Genomic Features and Gene Cluster Analysis of L. plantarum HYH-11

3.7. Comparison of Experimental Results and Analysis of Staining of Live and Dead Cells Under Fluorescence Microscopy

3.8. Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) Analysis

3.9. Hemolysis Test Measurement of BLIS UI-11

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Harikrishnan, R.; Balasundaram, C.J. Modern Trends in Aeromonas hydrophila Disease Management with Fish. Rev. Fish. Sci. 2005, 13, 281–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citterio, B.; Biavasco, F. Aeromonas hydrophila Virulence. Virulence 2015, 6, 417–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, M.J.A.; Rashid, M.M. Pathogenicity of the Bacterial Isolate Aeromonas hydrophila to Catfishes, Carps and Perch. J. Bangladesh Agric. Univ. 2012, 10, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nhinh, D.T.; Le, D.V.; Van, K.V.; Huong Giang, N.T.; Dang, L.T.; Hoai, T.D. Prevalence, Virulence Gene Distribution and Alarming the Multidrug Resistance of Aeromonas hydrophila Associated with Disease Outbreaks in Freshwater Aquaculture. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdella, B.; Shokrak, N.M.; Abozahra, N.A.; Elshamy, Y.M.; Kadira, H.I.; Mohamed, R.A. Aquaculture and Aeromonas hydrophila: A Complex Interplay of Environmental Factors and Virulence. Aquac. Int. 2024, 32, 7671–7681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M.V.; Dias, M.F.F.; Francisco, C.J.; David, G.S.; da Silva, R.J.; Júnior, J.P.A. Aeromonas hydrophila in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) from Brazilian aquaculture: A public health problem. Emergent Life Sci. Res. 2019, 5, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serwecińska, L. Antimicrobials and Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria: A Risk to the Environment and to Public Health. Water 2020, 12, 3313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chokshi, A.; Sifri, Z.; Cennimo, D.; Horng, H. Global Contributors to Antibiotic Resistance. J. Glob. Infect. Dis. 2019, 11, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Xie, Y. A Systematic Review on Antibiotics Misuse in Livestock and Aquaculture and Regulation Implications in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 798, 149205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limbu, S.M.; Chen, L.-Q.; Zhang, M.-L.; Du, Z.-Y. A Global Analysis on the Systemic Effects of Antibiotics in Cultured Fish and Their Potential Human Health Risk: A Review. Rev. Aquac. 2021, 13, 1015–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotter, P.D.; Ross, R.P.; Hill, C. Bacteriocins—A Viable Alternative to Antibiotics? Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2013, 11, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabo, S.S.; Vitolo, M.; González, J.M.D.; Oliveira, R.P.S. Overview of Lactobacillus plantarum as a Promising Bacteriocin Producer among Lactic Acid Bacteria. Food Res. Int. 2014, 64, 527–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayabaskar, P.; Somasundaram, S.T. Isolation of Bacteriocin Producing Lactic Acid Bacteria from Fish Gut and Probiotic Activity against Common Fresh Water Fish Pathogen Aeromonas hydrophila. Biotechnology 2008, 7, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Tian, Y.; Zhu, J.; Wen, R.; Chen, Q.; Kong, B. Technological Characterization and Flavor-Producing Potential of Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolated from Traditional Dry Fermented Sausages in Northeast China. Food Microbiol. 2022, 106, 104059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Yang, J.; He, P.; Wang, M.; Li, C.; Chen, G.; Rao, Y. Microbial Communities in Biofilm and Brine Samples during the Spoilage Process of Traditional Pickle. CABI Digit. Libr. 2016, 7, 305–313. [Google Scholar]

- Dinev, T.; Beev, G.; Tzanova, M.; Denev, S.; Dermendzhieva, D.; Stoyanova, A. Antimicrobial Activity of Lactobacillus plantarum against Pathogenic and Food Spoilage Microorganisms: A Review. Bulg. J. Vet. Med. 2018, 21, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vuyst, L.; Callewaert, R.; Crabbé, K. Primary Metabolite Kinetics of Bacteriocin Biosynthesis by Lactobacillus amylovorus and Evidence for Stimulation of Bacteriocin Production under Unfavourable Growth Conditions. Microbiology 1996, 142, 817–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, S.; Hammami, R.; Cotter, P.D.; Rebuffat, S.; Said, L.B.; Gaudreau, H.; Bédard, F.; Biron, E.; Drider, D.; Fliss, I. Bacteriocins as a New Generation of Antimicrobials: Toxicity Aspects and Regulations. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2021, 45, fuaa039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, E.; Dennison, S.R.; Harris, F.; Phoenix, D.A. pH Dependent Antimicrobial Peptides and Proteins, Their Mechanisms of Action and Potential as Therapeutic Agents. Pharmaceuticals 2016, 9, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chih, Y.-H.; Wang, S.-Y.; Yip, B.-S.; Cheng, K.-T.; Hsu, S.-Y.; Wu, C.-L.; Yu, H.-Y.; Cheng, J.-W. Dependence on Size and Shape of Non-Nature Amino Acids in the Enhancement of Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) Neutralizing Activities of Antimicrobial Peptides. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019, 533, 492–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, S.; Shirwaikar, A.A.; Srinivasan, K.K.; Alex, J.; Prabu, S.L.; Mahalaxmi, R.; Kumar, R. Stability of Proteins in Aqueous Solution and Solid State. Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 2006, 68, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smitha, S.; Bhat, S.G. Thermostable Bacteriocin BL8 from Bacillus licheniformis Isolated from Marine Sediment. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2013, 114, 688–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tull, D.; Gottschalk, T.E.; Svendsen, I.; Kramhøft, B.; Phillipson, B.A.; Bisgård-Frantzen, H.; Olsen, O.; Svensson, B. Extensive N-Glycosylation Reduces the Thermal Stability of a Recombinant Alkalophilic Bacillus α-Amylase Produced in Pichia pastoris. Protein Expr. Purif. 2001, 21, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebeling, W.; Hennrich, N.; Klockow, M.; Metz, H.; Orth, H.D.; Lang, H. Proteinase K from Tritirachium album Limber. Eur. J. Biochem. 1974, 47, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marciniszyn, J., Jr.; Huang, J.S.; Hartsuck, J.A.; Tang, J. Mechanism of Intramolecular Activation of Pepsinogen. Evidence for an Intermediate Delta and the Involvement of the Active Site of Pepsin in the Intramolecular Activation of Pepsinogen. J. Biol. Chem. 1976, 251, 7095–7102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, G. The Structure and Mechanism of Action of Papain. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 1970, 257, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Shea, E.F.; O’Connor, P.M.; Cotter, P.D.; Ross, R.P.; Hill, C. Synthesis of Trypsin-Resistant Variants of the Listeria-Active Bacteriocin Salivaricin P. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 5356–5362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narahashi, Y.; Yanagita, M. Studies on Proteolytic Enzymes (Pronase) of Streptomyces griseus K-1. J. Biochem. 1967, 62, 633–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Acharya, B.; Varadaraj, M.C.; Gowda, L.R.; Tharanathan, R.N. Characterization of Chito-Oligosaccharides Prepared by Chitosanolysis with the Aid of Papain and Pronase, and Their Bactericidal Action against Bacillus cereus and Escherichia coli. Biochem. J. 2005, 391, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves-Petersen, M.T.; Gajula, G.P.; Petersen, S.B. UV Light Effects on Proteins: From Photochemistry to Nanomedicine. In Molecular Photochemistry—Various Aspects; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2012; pp. 125–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, R.C.R.; Wachsman, M.; Torres, N.I.; LeBlanc, J.G.; Todorov, S.D.; Franco, B.D.G.M. Biochemical, Antimicrobial and Molecular Characterization of a Noncytotoxic Bacteriocin Produced by Lactobacillus plantarum ST71KS. Food Microbiol. 2013, 34, 376–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.-F.; Zhu, M.-Y.; Gu, Q. Purification and Characterization of Plantaricin ZJ5, a New Bacteriocin Produced by Lactobacillus plantarum ZJ5. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e105549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Q.; Zhang, M.; Xue, R.; Liu, T.; Yang, Z.; Yang, Z. Purification and Characterization of a Novel Low-Molecular-Weight Antimicrobial Peptide Produced by Lactiplantibacillus plantarum NMGL2. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 248, 125932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, C.; Fan, S.; Deng, F.; Zhao, L. A Novel Bacteriocin Isolated from Lactobacillus plantarum W3-2 and Its Biological Characteristics. Front. Nutr. 2023, 9, 1111880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kloosterman, A.M.; Shelton, K.E.; van Wezel, G.P.; Medema, M.H.; Mitchell, D.A. RRE-Finder: A Genome-Mining Tool for Class-Independent RiPP Discovery. mSystems 2020, 5, e00267-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias-Orozco, P.; Zhou, L.; Yi, Y.; Cebrián, R.; Kuipers, O.P. Uncovering the Diversity and Distribution of Biosynthetic Gene Clusters of Prochlorosins and Other Putative RiPPs in Marine Synechococcus Strains. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e03611-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderssen, E.L.; Diep, D.B.; Nes, I.F.; Eijsink, V.G.H.; Nissen-Meyer, J. Antagonistic Activity of Lactobacillus plantarum C11: Two New Two-Peptide Bacteriocins, Plantaricins EF and JK, and the Induction Factor Plantaricin A. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1998, 64, 2269–2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekblad, B.; Kyriakou, P.K.; Oppegård, C.; Nissen-Meyer, J.; Kaznessis, Y.N.; Kristiansen, P.E. Structure–Function Analysis of the Two-Peptide Bacteriocin Plantaricin EF. Biochemistry 2016, 55, 5106–5116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnison, P.G.; Bibb, M.J.; Bierbaum, G.; Bowers, A.A.; Bugni, T.S.; Bulaj, G.; Camarero, J.A.; Campopiano, D.J.; Challis, G.L. Ribosomally Synthesized and Post-Translationally Modified Peptide Natural Products: Overview and Recommendations for a Universal Nomenclature. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2013, 30, 108–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warwick, T.G. Structural Studies on Staphylococcus aureus Quorum Sensing Proteins AgrA and AgrB. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, S.K.; Rajasree, K.; Fasim, A.; Arakere, G.; Gopal, B. Influence of the AgrC-AgrA Complex on the Response Time of Staphylococcus aureus Quorum Sensing. J. Bacteriol. 2014, 196, 2876–2888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontaine, L.; Boutry, C.; Guédon, E.; Guillot, A.; Ibrahim, M.; Grossiord, B.; Hols, P. Quorum-Sensing Regulation of the Production of Blp Bacteriocins in Streptococcus thermophilus. J. Bacteriol. 2007, 189, 7195–7205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Saizieu, A.; Gardès, C.; Flint, N.; Wagner, C.; Kamber, M.; Mitchell, T.J.; Keck, W.; Amrein, K.E.; Lange, R. Microarray-Based Identification of a Novel Streptococcus pneumoniae Regulon Controlled by an Autoinduced Peptide. J. Bacteriol. 2000, 182, 4696–4703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majchrzykiewicz, J.A.; Kuipers, O.P.; Bijlsma, J.J.E. Generic and Specific Adaptive Responses of Streptococcus pneumoniae to Challenge with Three Distinct Antimicrobial Peptides, Bacitracin, LL-37, and Nisin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 440–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, E.L.; Abrudan, M.I.; Roberts, I.S.; Rozen, D.E. Diverse Ecological Strategies Are Encoded by Streptococcus pneumoniae Bacteriocin-like Peptides. Genome Biol. Evol. 2016, 8, 1072–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negash, A.W.; Tsehai, B.A. Current Applications of Bacteriocin. Int. J. Microbiol. 2020, 2020, 4374891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacharof, M.-P.; Lovitt, R.W. Bacteriocins Produced by Lactic Acid Bacteria a Review Article. Apcbee Procedia 2012, 2, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; She, P.; Li, Z.; Li, Y.; Yang, Y.; Li, L.; Zhou, L.; Wu, Y. Insights into the Antimicrobial Effects of Ceritinib against Staphylococcus aureus In Vitro and In Vivo by Cell Membrane Disruption. AMB Express 2022, 12, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Wu, H.; Zou, Y.; Li, P.; Sun, C.; Xu, W.; Liu, F.; Wang, D. Class III Bacteriocin Helveticin-M Causes Sublethal Damage on Target Cells through Impairment of Cell Wall and Membrane. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 45, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, L.; Wei, Y.; Shang, N.; Zhang, X.; Li, P. Two-Peptide Bacteriocin PlnEF Causes Cell Membrane Damage to Lactobacillus plantarum. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2016, 1858, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, H.; Chang, Y.H.; Yune, J.H.; Jeong, C.H.; Shin, D.M.; Kwon, H.C.; Kim, D.H.; Hong, S.W.; Hwang, H.; Jeong, J.Y.; et al. Probiotic Properties of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum LB5 Isolated from Kimchi Based on Nitrate Reducing Capability. Foods 2020, 9, 1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lad, V.; Panchal, D.; Pithawala, M.; Dwivedi, M.K.; Amaresan, N. Determination of Hemolytic Activity. In Biosafety Assessment of Probiotic Potential; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 43–46. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, J.L.; Yates, E.A.; Bielecki, M.; Olczak, T.; Smalley, J.W. Potential Role for Streptococcus gordonii-Derived Hydrogen Peroxide in Heme Acquisition by Porphyromonas gingivalis. Mol. Oral Microbiol. 2018, 33, 322–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, C.; Li, X.; Liu, J.; Gu, J.; Gao, F.; Sun, J.; Pang, X.; Lu, Y. Different Oligosaccharides and Sodium Caseinate Glycosylated Conjugates for the Microencapsulation of Lactobacillus fermentum to Improve Stability and Cholesterol-Lowering Activity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 334, 149167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcena, A.J.; Nakpil, A.; Gloriani, N.; Medina, P.M. Lowland and Highland Varieties of Dioscorea esculenta Tubers Stimulate Growth of Lactobacillus sp. over Enterotoxigenic E. coli In Vitro. Acta Med. Philipp. 2022, 56, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Indicator Strains | Source | Gram | Inhibition Zone (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gram-negative bacteria | |||

| A. hydrophila | ATCC 6799 | −ve | 31.45 ± 0.47 |

| A. hydrophila | HYH-C12 | −ve | 30.97 ± 0.62 |

| A. salmonicida | XN-9 | −ve | 29.67 ± 0.33 |

| A. dhakensis | HYH-B11 | −ve | 27.13 ± 0.24 |

| E. coli | ATCC 25922 | −ve | 24.56 ± 0.34 |

| S. Typhimurium | ATCC 14028 | −ve | 23.41 ± 0.29 |

| Gram-positive bacteria | |||

| S. aureus | ATCC 25923 | +ve | 24.68 ± 0.56 |

| L. monocytogenes | ATCC 19115 | +ve | 26.55 ± 0.52 |

| V. fluvialis | HYH-B7 | +ve | 28.20 ± 0.49 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

He, Y.; Tang, D.; Lin, J.; Zhang, J.; Sha, W.; Dong, W. A Small-Molecular-Weight Bacteriocin-like Inhibitory Substance (BLIS) UI-11 Produced by Lactobacillus plantarum HYH-11 as an Antimicrobial Agent for Aeromonas hydrophila. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 1165. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci12121165

He Y, Tang D, Lin J, Zhang J, Sha W, Dong W. A Small-Molecular-Weight Bacteriocin-like Inhibitory Substance (BLIS) UI-11 Produced by Lactobacillus plantarum HYH-11 as an Antimicrobial Agent for Aeromonas hydrophila. Veterinary Sciences. 2025; 12(12):1165. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci12121165

Chicago/Turabian StyleHe, Yinghui, Donghui Tang, Jiarui Lin, Jiayue Zhang, Wanli Sha, and Wenlong Dong. 2025. "A Small-Molecular-Weight Bacteriocin-like Inhibitory Substance (BLIS) UI-11 Produced by Lactobacillus plantarum HYH-11 as an Antimicrobial Agent for Aeromonas hydrophila" Veterinary Sciences 12, no. 12: 1165. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci12121165

APA StyleHe, Y., Tang, D., Lin, J., Zhang, J., Sha, W., & Dong, W. (2025). A Small-Molecular-Weight Bacteriocin-like Inhibitory Substance (BLIS) UI-11 Produced by Lactobacillus plantarum HYH-11 as an Antimicrobial Agent for Aeromonas hydrophila. Veterinary Sciences, 12(12), 1165. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci12121165