Seeking Sweetness: A Systematic Scoping Review of Factors Influencing Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Consumption in Remote Indigenous Communities Worldwide

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Selection Process and Data Collection

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Data Synthesis

2.6. Quality Assessment

3. Results

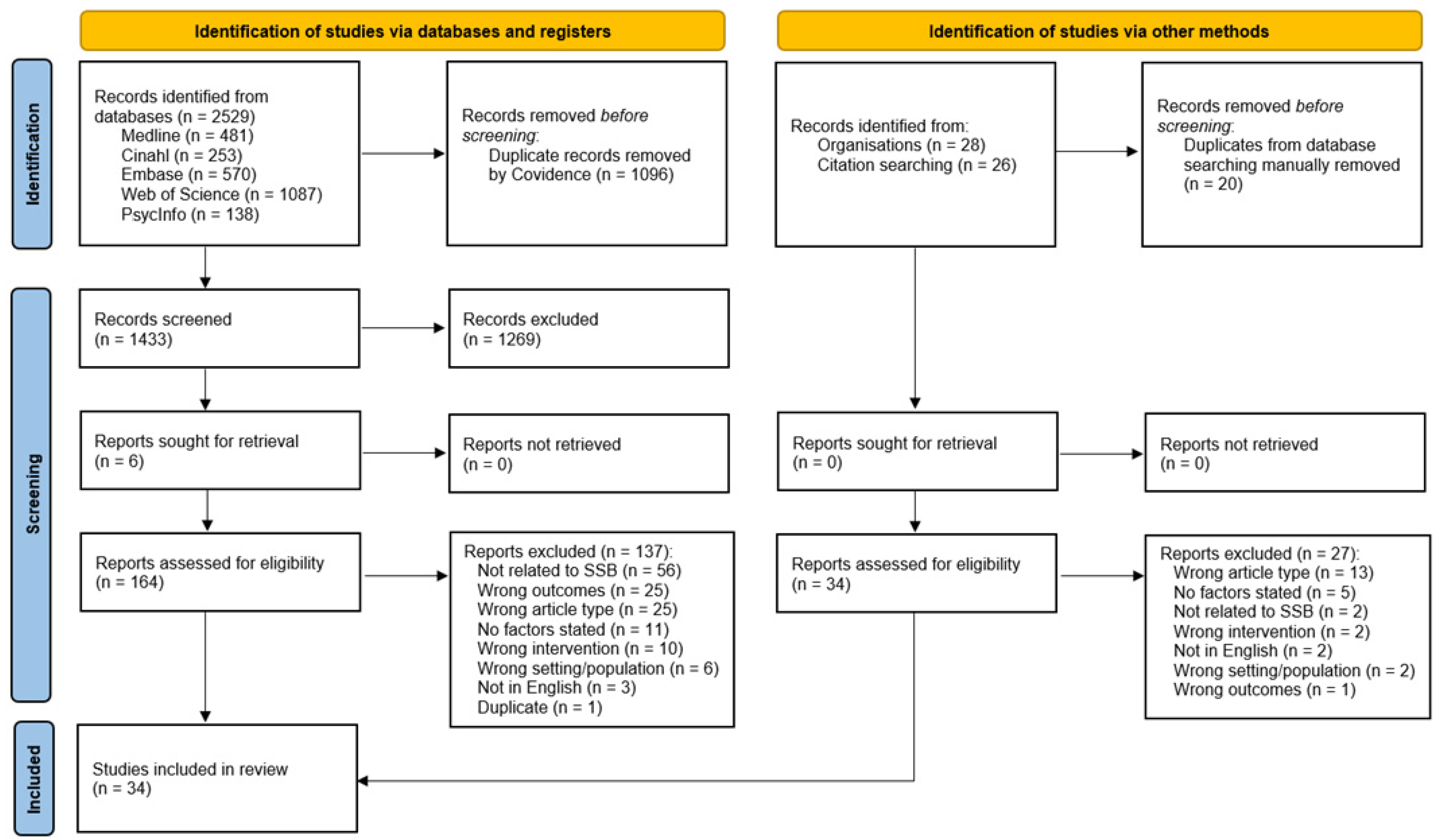

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Quality Assessment

3.3. Study Characteristics

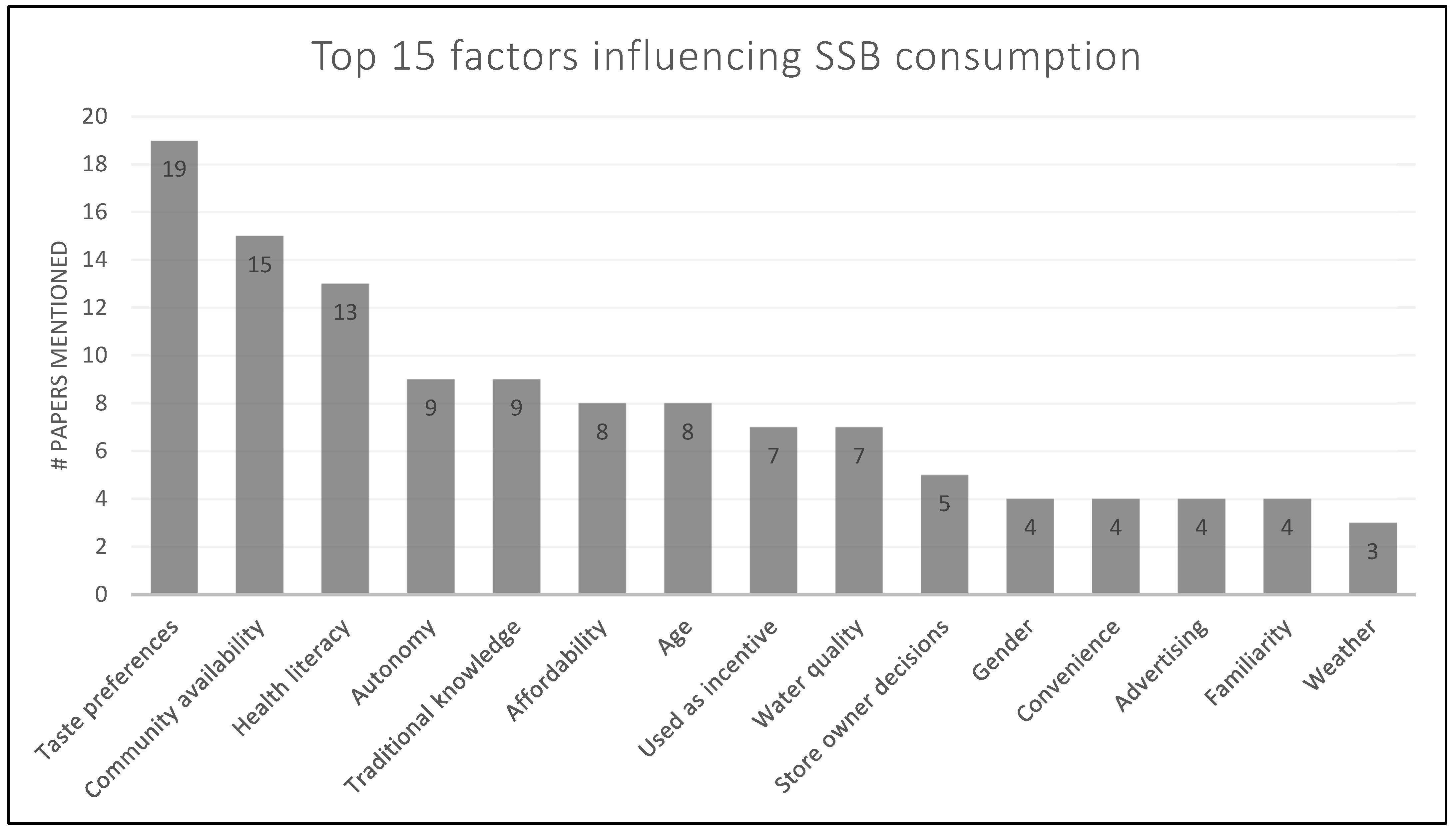

3.4. Review Outcomes

3.4.1. Individual Level

3.4.2. Interpersonal Level

3.4.3. Environmental Level

3.4.4. Policy Level

4. Discussion

4.1. Individual Level Factors Moderating SSB Intake

4.2. Interpersonal Level Factors Moderating SSB Intake

4.3. Environmental Level Factors Moderating SSB Intake

4.4. Policy Level Factors Moderating SSB Intake

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ferdinand, A.; Lambert, M.; Trad, L.; Pedrana, L.; Paradies, Y.; Kelaher, M. Indigenous engagement in health: Lessons from Brazil, Chile, Australia and New Zealand. Int. J. Equity Health 2020, 19, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations. State of the World’s Indigenous Peoples: Indigenous Peoples’ Access to Health Services. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/wp-content/uploads/sites/19/2018/03/The-State-of-The-Worlds-Indigenous-Peoples-WEB.pdf (accessed on 8 September 2022).

- Harris, S.B.; Tompkins, J.W.; TeHiwi, B. Call to Action: A New Path for Improving Diabetes Care for Indigenous Peoples, a Global Review. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2016, 123, 120–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, F.; Owen, N.; Oddy, W.H. Sugar sweetened beverages and increasing prevalence of type 2 diabetes in the Indigenous community of Australia. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2021, 31, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health. 2004. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9241592222 (accessed on 4 May 2022).

- Johnson, R.J.; Perez-Pozo, S.E.; Sautin, Y.Y.; Manitius, J.; Sanchez-Lozada, L.G.; Feig, D.I.; Shafiu, M.; Segal, M.; Glassock, R.J.; Shimada, M.; et al. Hypothesis: Could Excessive Fructose Intake and Uric Acid Cause Type 2 Diabetes? Endocr. Rev. 2009, 30, 96–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moodie, R.; Stuckler, D.; Monteiro, C.; Sheron, N.; Neal, B.; Thamarangsi, T.; Lincoln, P.; Casswell, S. Profits and pandemics: Prevention of harmful effects of tobacco, alcohol, and ultra-processed food and drink industries. Lancet 2013, 381, 670–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, K.M.; Dono, J.; Brownbill, A.L.; Pearson, O.; Bowden, J.; Wycherley, T.P.; Keech, W.; O’Dea, K.; Roder, D.; Avery, J.C.; et al. Sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) consumption, correlates and interventions among Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities: A scoping review. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e023630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imamura, F.; O’Connor, L.; Ye, Z.; Mursu, J.; Hayashino, Y.; Bhupathiraju, S.N.; Forouhi, N.G. Consumption of sugar sweetened beverages, artificially sweetened beverages, and fruit juice and incidence of type 2 diabetes: Systematic review, meta-analysis, and estimation of population attributable fraction. Br. J. Sports Med. 2016, 50, 496–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drewnowski, A.; Tappy, L.; Forde, C.G.; McCrickerd, K.; Tee, E.S.; Chan, P.; Amin, L.; Trinidad, T.P.; Amarra, M.S. Sugars and sweeteners: Science, innovations, and consumer guidance for Asia. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 28, 645–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennessy, T.W.; Whistler, B.; Bruce, M.G.; Rolin, S.; Beltrdn-Aguilar, E.; Swanzy, M.; Byrd, K.K.; Husain, F.; Klejka, J.; Jones, C.; et al. Dental Caries in Rural Alaska Native Children—Alaska, 2008. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2011, 60, 1275–1278. [Google Scholar]

- Stroehla, B.C.; Malcoe, L.H.; Velie, E.M. Dietary Sources of Nutrients among Rural Native American and White Children. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2005, 105, 1908–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bersamin, A.; Herron, J.; Nash, S.; Maier, J.; Luick, B. Characterizing beverage patterns among Alaska Natives living in rural, remote communities: The CANHR study. FASEB J. 2011, 25, 991.11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, T.J.; Haardörfer, R.; Greene, B.M.; Parulekar, S.; Kegler, M.C. Beverage consumption patterns among overweight and obese African American women. Nutr. J. 2017, 9, 1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennison, M.E.; Sisson, S.B.; Lora, K.; Stephens, L.D.; Copeland, K.C.; Caudillo, C. Assessment of Body Mass Index, Sugar Sweetened Beverage Intake and Time Spent in Physical Activity of American Indian Children in Oklahoma. J. Community Health 2015, 40, 808–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebuli, M.A.; Hendrie, G.A.; Baird, D.L.; Mahoney, R.; Riley, M.D. Beverage Intake and Associated Nutrient Contribution for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians: Secondary Analysis of a National Dietary Survey 2012–2013. Nutr. J. 2022, 14, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 4727.0.55.009—Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey: Consumption of Added Sugars, 2012–2013. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/by%20Subject/4727.0.55.009~2012-13~Main%20Features~Key%20Findings~1 (accessed on 24 April 2022).

- Leonard, D.; Aquino, D.; Hadgraft, N.; Thompson, F.; Marley, J.V. Poor nutrition from first foods: A cross-sectional study of complementary feeding of infants and young children in six remote Aboriginal communities across northern Australia: Poor nutrition from first foods in remote northern Australia. Nutr. Diet. 2017, 74, 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Health and Medical Research Council. Infant Feeding Guidelines: Summary. Available online: https://www.eatforhealth.gov.au/sites/default/files/files/the_guidelines/n56_infant_feeding_guidelines_summary_150916.pdf (accessed on 18 June 2022).

- National Health and Medical Research Council. Australian dietary guidelines—Providing the scientific evidence for healthier Australian diets. Available online: https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/adg (accessed on 18 June 2022).

- Lee, A.; Rainow, S.; Tregenza, J.; Tregenza, L.; Balmer, L.; Bryce, S.; Paddy, M.; Sheard, J.; Schomburgk, D. Nutrition in remote Aboriginal communities: Lessons from Mai Wiru and the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Lands. Aust. New Zealand J. Public Health 2016, 40, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, M.; O’Dea, K.; Altman, J.; Moodie, M.; Brimblecombe, J. Health-promoting food pricing policies and decision-making in very remote aboriginal and torres strait islander community stores in Australia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockburn, N.; Lalloo, R.; Schubert, L.; Ford, P.J. Beverage consumption in Australian children. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 72, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahns, L.; McDonald, L.; Wadsworth, A.; Morin, C.; Liu, Y.; Nicklas, T. Barriers and facilitators to following the Dietary Guidelines for Americans reported by rural, Northern Plains American-Indian children. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 482–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, J.; Lock, M.; Walker, T.; Egan, M.; Backholer, K. Effects of food policy actions on Indigenous Peoples’ nutrition-related outcomes: A systematic review. BMJ Global Health 2020, 5, e002442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winn, M.T.; Paris, D. R-words: Refusing Research. In Humanizing Research: Decolonizing Qualitative Inquiry with Youth and Communities; SAGE Publications Inc.: London, UK, 2014; ISBN 9781452225395. [Google Scholar]

- Kirmayer, L.J.; Brass, G. Addressing global health disparities among Indigenous peoples. Lancet 2016, 388, 105–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations. Indigenous Peoples and the 2030 Agenda. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/focus-areas/post-2015-agenda/the-sustainable-development-goals-sdgs-and-indigenous.html (accessed on 5 May 2022).

- PRISMA. Welcome to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) website. Available online: https://www.prisma-statement.org/ (accessed on 24 April 2022).

- Bond University. SR-Accelerator. Available online: https://sr-accelerator.com/#/polyglot (accessed on 24 April 2022).

- Covidence. Better systematic review management. Available online: https://www.covidence.org/ (accessed on 24 April 2022).

- Stok, F.M.; Hoffmann, S.; Volkert, D.; Boeing, H.; Ensenauer, R.; Stelmach-Mardas, M.; Kiesswetter, E.; Weber, A.; Rohm, H.; Lien, N.; et al. The DONE framework: Creation, evaluation, and updating of an interdisciplinary, dynamic framework 2.0 of determinants of nutrition and eating. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q.N.; Fàbregues Feijóo, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; O’Cathain, A.; et al. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ. Inf. 2018, 34, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailie, R.S.; Carson, B.E.; McDonald, E.L. Water supply and sanitation in remote Indigenous communities-priorities for health development. Aust. New Zealand J. Public Health 2004, 28, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brimblecombe, J.; Maypilama, E.; Colles, S.; Scarlett, M.; Dhurrkay, J.G.; Ritchie, J.; O’Dea, K. Factors Influencing Food Choice in an Australian Aboriginal Community. Qual. Health Res. 2014, 24, 387–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byker Shanks, C.; Ahmed, S.; Dupuis, V.; Houghtaling, B.; Running Crane, M.A.; Tryon, M.; Pierre, M. Perceptions of food environments and nutrition among residents of the Flathead Indian Reservation. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakona, G. Social circumstances and cultural beliefs influence maternal nutrition, breastfeeding and child feeding practices in South Africa. Nutr. J. 2020, 19, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colles, S.L.; Maypilama, E.; Brimblecombe, J. Food, food choice and nutrition promotion in a remote Australian Aboriginal community. Aust. J. Prim. Health 2014, 20, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitropoulos, Y.; Gunasekera, H.; Blinkhorn, A.; Byun, R.; Binge, N.; Gwynne, K.; Irving, M. A collaboration with local Aboriginal communities in rural New South Wales, Australia to determine the oral health needs of their children and develop a community-owned oral health promotion program. Rural. Remote. Health 2018, 18, 4453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elwan, D.; Schweinitz, P.D.; Wojcicki, J.M. Beverage consumption in an Alaska Native village: A mixed-methods study of behaviour, attitudes and access. Int. J. Circumpolar. Health 2016, 75, 29905–29910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, S.M.; Durden, T.E. Two approaches, one problem: Cultural constructions of type II diabetes in an indigenous community in Yucatán, Mexico. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 172, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galloway, T.; Johnson-Down, L.; Egeland, G.M. Socioeconomic and Cultural Correlates of Diet Quality in the Canadian Arctic: Results from the 2007-2008 Inuit Health Survey. Can. J. Diet Pract. Res. 2015, 76, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godrich, S.L.; Davies, C.R.; Darby, J.; Devine, A. What are the determinants of food security among regional and remote Western Australian children? Aust. New Zealand J. Public Health 2017, 41, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, N.L. Challenges of WASH in remote Australian indigenous communities. J. Water Sanit. Hyg. Dev. 2019, 9, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson-Down, L.M.; Egeland, G.M. How is nutrition transition affecting dietary adequacy in Eeyouch (Cree) adults of Northern Quebec, Canada? Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2013, 38, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkham, R.; King, S.; Graham, S.; Boyle, J.A.; Whitbread, C.; Skinner, T.; Rumbold, A.; Maple-Brown, L. ‘No sugar’, ‘no junk food’, ‘do more exercise’—Moving beyond simple messages to improve the health of Aboriginal women with Hyperglycaemia in Pregnancy in the Northern Territory—A phenomenological study. Women Birth 2021, 34, 578–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koller, K.R.; Flanagan, C.A.; Nu, J.; Lee, F.; Desnoyers, C.; Walch, A.; Alexie, L.; Bersamin, A.; Thomas, T.K. Storekeeper perspectives on improving dietary intake in 12 rural remote western Alaska communities: The "Got Neqpiaq?" project. Int. J. Circumpolar. Health 2021, 80, 1961393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruske, S.; Belton, S.; Wardaguga, M.; Narjic, C. Growing Up Our Way: The First Year of Life in Remote Aboriginal Australia. Qual. Health. Res. 2012, 22, 777–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurschner, S.; Madrigal, L.; Chacon, V.; Barnoya, J.; Rohloff, P. Impact of school and work status on diet and physical activity in rural Guatemalan adolescent girls: A qualitative study. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2020, 1468, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyoon-Achan, G.; Schroth, R.J.; DeMaré, D.; Sturym, M.; Edwards, J.M.; Sanguins, J.; Campbell, R.; Chartrand, F.; Bertone, M.; Moffatt, M.E.K. First Nations and Metis peoples’ access and equity challenges with early childhood oral health: A qualitative study. Int. J. Equity Health 2021, 20, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, A.; Sokal-Gutierrez, K.; Hargrave, A.; Funsch, E.; Hoeft, K.S. Maintaining traditions: A qualitative study of early childhood caries risk and protective factors in an indigenous community. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindsay, A.C.; Tavares Machado, M.; Sussner, K.M.; Hardwick, C.K.; Sansigolo Kerr, L.R.F.; Peterson, K.E. Brazilian mothers’ beliefs, attitudes, and practices related to child weight status and early feeding within the context of nutrition transition. J. Biosoc. Sci. 2009, 41, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myers, J.; Thorpe, S.; Browne, J.; Gibbons, K.; Brown, S. Early childhood nutrition concerns, resources and services for Aboriginal families in Victoria. Aust. New Zealand J. Public Health 2014, 38, 370–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, J.; Durey, A.; Naoum, S.; Kruger, E.; Slack-Smith, L. Oral health education and prevention strategies among remote Aboriginal communities: A qualitative study. Aust. Dent. J. 2022, 67, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollard, C.M.; Nyaradi, A.; Lester, M.; Sauer, K. Understanding food security issues in remote Western Australian Indigenous communities. Health Promot. J. Austr. 2014, 25, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A.; Hanrahan, M.; Hudson, A. Water insecurity in Canadian Indigenous communities: Some inconvenient truths. Rural Remote Health 2015, 15, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seear, K.H.; Atkinson, D.N.; Henderson-Yates, L.M.; Lelievre, M.P.; Marley, J.V. Maboo wirriya, be healthy: Community-directed development of an evidence-based diabetes prevention program for young Aboriginal people in a remote Australian town. Eval. Program Plan. 2020, 81, 101818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurber, K.A.; Bagheri, N.; Banwell, C. Social determinants of sugar-sweetened beverage consumption in the Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children. Fam. Matters 2014, 95, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurber, K.A.; Long, J.; Salmon, M.; Cuevas, A.G.; Lovett, R. Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption among Indigenous Australian children aged 0-3 years and association with sociodemographic, life circumstances and health factors. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 23, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomayko, E.J.; Mosso, K.L.; Cronin, K.A.; Carmichael, L.; Kim, K.; Parker, T.; Yaroch, A.L.; Adams, A.K. Household food insecurity and dietary patterns in rural and urban American Indian families with young children. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonkin, E.; Jeffs, L.; Wycherley, T.P.; Maher, C.; Smith, R.; Hart, J.; Cubillo, B.; Hum Nut, B.; Brimblecombe, J. A smartphone app to reduce sugar-sweetened beverage consumption among young adults in Australian remote indigenous communities: Design, formative evaluation and user-testing. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2017, 5, e192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walch, A.K.; Ohle, K.A.; Koller, K.R.; Alexie, L.; Lee, F.; Palmer, L.; Nu, J.; Thomas, T.K.; Bersamin, A. Impact of Assistance Programs on Indigenous Ways of Life in 12 Rural Remote Western Alaska Native Communities: Elder Perspectives Shared in Formative Work for the "Got Neqpiaq?" Project. Int. J. Circumpolar. Health 2022, 81, 2024679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walch, A.K.; Ohle, K.A.; Koller, K.R.; Alexie, L.; Sapp, F.; Thomas, T.K.; Bersamin, A. Alaska Native Elders’ perspectives on dietary patterns in rural, remote communities. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wattelez, G.; Frayon, S.; Cavaloc, Y.; Cherrier, S.; Lerrant, Y.; Galy, O. Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption and associated factors in school-going adolescents of New Caledonia. Nutr. J. 2019, 11, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, A.J.; Graham, S.; Boyle, J.A.; Marcusson-Rababi, B.; Anderson, S.; Connors, C.; McIntyre, H.D.; Maple-Brown, L.; Kirkham, R. Incorporating Aboriginal women’s voices in improving care and reducing risk for women with diabetes in pregnancy—A phenomenological study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021, 21, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wycherley, T.P.; Van Der Pols, J.C.; Daniel, M.; Howard, N.J.; O’Dea, K.; Brimblecombe, J.K. Associations between community environmental-level factors and diet quality in geographically isolated Australian communities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoellner, J.; You, W.; Connell, C.; Smith-Ray, R.L.; Allen, K.; Tucker, K.L.; Davy, B.M.; Estabrooks, P. Health Literacy Is Associated with Healthy Eating Index Scores and Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Intake: Findings from the Rural Lower Mississippi Delta. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2011, 111, 1012–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, S.J. Food and nutrition policy issues in remote Aboriginal communities: Lessons from Arnhem Land. Aust. J. Public Health 1991, 15, 281–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowitja Institute. Close the Gap Campaign Report 2022—Transforming Power: Voices for Generational Change. Available online: https://www.lowitja.org.au/content/Document/Lowitja-Publishing/ClosetheGapReport_2022.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2022).

- Desor, J.A.; Beauchamp, G.K. Longitudinal changes in sweet preferences in humans. Physiol. Behav. 1987, 39, 639–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadhoke, P. Structure, culture, and agency: Framing a child as change agent approach for adult obesity prevention in American Indian households. Doctoral Thesis, The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gracey, M.P.; King, M.P. Indigenous health part 1: Determinants and disease patterns. Lancet 2009, 374, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, E.J.; Jamieson, L.M. Associations between indigenous Australian oral health literacy and self-reported oral health outcomes. BMC Oral Health 2010, 10, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keleher, H.; Hagger, V. Health literacy in primary health care. Aust. J. Prim. Health 2007, 13, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brimblecombe, J.; Ferguson, M.; Chatfield, M.D.; Liberato, S.C.; Gunther, A.; Ball, K.; Moodie, M.; Miles, E.; Magnus, A.; Mhurchu, C.N.; et al. Effect of a price discount and consumer education strategy on food and beverage purchases in remote Indigenous Australia: A stepped-wedge randomised controlled trial. Lancet Public Health 2017, 2, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dono, J.; Ettridge, K.; Wakefield, M.; Pettigrew, S.; Coveney, J.; Roder, D.; Durkin, S.; Wittert, G.; Martin, J.; Miller, C. Nothing beats taste or convenience: A national survey of where and why people buy sugary drinks in Australia. Aust. New Zealand J. Public Health 2020, 44, 291–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepino, M.Y.; Mennella, J.A. Factors Contributing to Individual Differences in Sucrose Preference. Chem. Senses 2005, 30, 319–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, A. Nature and Nurture: Aboriginal Childrearing in North-Central Arnhem Land; Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies: Canberra, Australia, 1981; ISBN 0855751126. [Google Scholar]

- Hoare, A.; Virgo-Milton, M.; Boak, R.; Gold, L.; Waters, E.; Gussy, M.; Calache, H.; Smith, M.; De Silva, A.M. A qualitative study of the factors that influence mothers when choosing drinks for their young children. BMC Res. Notes 2014, 7, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dussart, F. Diet, Diabetes and Relatedness in a Central Australian Aboriginal Settlement: Some Qualitative Recommendations to Facilitate the Creation of Culturally Sensitive Health Promotion Initiatives. Health Promot. J. Austr. 2009, 20, 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, M.; Hagar, H.; Zivot, C.; Dodd, W.; Skinner, K.; Kenny, T.; Caughey, A.; Gaupholm, J.; Lemire, M. Drivers and health implications of the dietary transition among Inuit in the Canadian Arctic: A scoping review. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 2650–2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grijalba, R.F. Breakfast in Paraguay: Quantitative and Qualitative Aspects. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2017, 71, 246. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, R.; Tapsell, L.; Lyons-Wall, P. Trends in purchasing patterns of sugar-sweetened water-based beverages in a remote Aboriginal community store following the implementation of a community-developed store nutrition policy. Nutr. Diet. 2011, 68, 115–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Human rights to safe drinking water and sanitation of indigenous peoples: State of affairs and lessons from ancestral cultures. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/documents/issues/water/2022-11-04/A-HRC-51-24-Friendly-version-EN.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2022).

- Public Health Advocacy Institute. Soft Drink Consumption in Aboriginal Communities Western Australia. Available online: https://www.phaiwa.org.au/soft-drink-consumption-in-aboriginal-communities/ (accessed on 30 October 2022).

- Dibay Moghadam, S.; Krieger, J.W.; Louden, D.K.N. A systematic review of the effectiveness of promoting water intake to reduce sugar-sweetened beverage consumption. Obes. Sci. Pract. 2020, 6, 229–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database | Search String | #Papers Retrieved |

|---|---|---|

| Embase | (aborigin*:ti,ab OR ‘torres strait island*’:ti,ab OR indigen*:ti,ab OR ‘first natio*’:ti,ab OR maori:ti,ab OR aotearoa:ti,ab OR ‘first people*’:ti,ab OR ‘native people*’:ti,ab OR ‘native born’:ti,ab OR metis:ti,ab OR inuit*:ti,ab OR ‘african america*’:ti,ab OR ‘native america*’:ti,ab OR ‘american india*’:ti,ab OR amerindian*:ti,ab OR eskimo*:ti,ab OR ‘native canad*’:ti,ab OR ‘first america*’:ti,ab OR ‘indigenous america*’:ti,ab OR saami:ti,ab OR sami:ti,ab OR greenlandic*:ti,ab OR nunavut*:ti,ab OR ‘first australia*’:ti,ab OR ‘alaska native*’:ti,ab OR ‘alaskan native*’:ti,ab OR ‘native hawaiian*’:ti,ab OR natives:ti,ab OR ‘alaska native’/exp OR ‘american indian’/exp OR ‘canadian aboriginal’/exp OR ‘indigenous people’/exp/mj OR ‘torres strait islander’/exp OR ‘australian aborigine’/exp) AND (remote:ti,ab OR isolated:ti,ab OR rural:ti,ab OR secluded:ti,ab OR regional:ti,ab OR ‘rural population’/exp) AND ((((soft OR sugar* OR fizzy OR energy OR carbonated OR discretionary OR ‘sugar sweetened’ OR ‘sugar-sweetened’ OR ‘sucrose sweetened’ OR ‘sucrose-sweetened’) NEAR/3 (beverage* OR drink*)):ti,ab) OR cordial*:ti,ab OR juice*:ti,ab OR soda*:ti,ab OR ‘coca cola’:ti,ab OR coke:ti,ab OR softdrink*:ti,ab OR ‘sugar-sweetened beverage’/exp OR (((diet* OR food* OR drink*) NEAR/3 (qualit* OR preference* OR choice* OR pattern*)):ti,ab) OR ‘food secur*’:ti,ab OR ‘food insecur*’:ti,ab OR ‘food preference’/exp) | 570 |

| CINAHL | (((TI Aborigin* OR AB Aborigin*) OR (TI “torres strait island*” OR AB “torres strait island*”) OR (TI Indigen* OR AB Indigen*) OR (TI “first natio*” OR AB “first natio*”) OR (TI Maori OR AB Maori) OR (TI Aotearoa OR AB Aotearoa) OR (TI “first people*” OR AB “first people*”) OR (TI “native people*” OR AB “native people*”) OR (TI “native born” OR AB “native born”) OR (TI Metis OR AB Metis) OR (TI Inuit* OR AB Inuit*) OR (TI “African America*” OR AB “African America*”) OR (TI “Native America*” OR AB “Native America*”) OR (TI “American India*” OR AB “American India*”) OR (TI Amerindian* OR AB Amerindian*) OR (TI Eskimo* OR AB Eskimo*) OR (TI “Native Canad*” OR AB “Native Canad*”) OR (TI “First America*” OR AB “First America*”) OR (TI “Indigenous America*” OR AB “Indigenous America*”) OR (TI Saami OR AB Saami) OR (TI Sami OR AB Sami) OR (TI Greenlandic* OR AB Greenlandic*) OR (TI Nunavut* OR AB Nunavut*) OR (TI “first Australia*” OR AB “first Australia*”) OR (TI “Alaska Native*” OR AB “Alaska Native*”) OR (TI “Alaskan Native*” OR AB “Alaskan Native*”) OR (TI “Native Hawaiian*” OR AB “Native Hawaiian*”) OR (TI natives OR AB natives)) OR (MH “Native Americans+”) OR (MM “Alaska Natives”) OR (MH “Aboriginal Canadians+”) OR (MH “Indigenous Peoples+”) OR (MM “Torres Strait Islanders”) OR (MM “Aboriginal Australians”) OR (MH “First Nations of Australia+”)) AND (((TI Remote OR AB Remote) OR (TI Isolated OR AB Isolated) OR (TI rural OR AB rural) OR (TI secluded OR AB secluded) OR (TI regional OR AB regional)) OR (MM “Rural Population”)) AND (((((TI soft OR AB soft) OR (TI sugar* OR AB sugar*) OR (TI fizzy OR AB fizzy) OR (TI energy OR AB energy) OR (TI carbonated OR AB carbonated) OR (TI discretionary OR AB discretionary) OR (TI “sugar sweetened” OR AB “sugar sweetened”) OR (TI “sucrose sweetened” OR AB “sucrose sweetened”) OR (TI sucrose-sweetened OR AB sucrose-sweetened) OR (TI sugar-sweetened OR AB sugar-sweetened)) N3 ((TI beverage* OR AB beverage*) OR (TI drink* OR AB drink*))) OR ((TI cordial* OR AB cordial*) OR (TI juice* OR AB juice*) OR (TI soda* OR AB soda*) OR (TI “coca cola” OR AB “coca cola”) OR (TI coke OR AB coke) OR (TI softdrink* OR AB softdrink*))) OR (MM “Sweetened Beverages”) OR (((((TI Diet* OR AB Diet*) OR (TI food* OR AB food*) OR (TI drink* OR AB drink*)) N3 ((TI qualit* OR AB qualit*) OR (TI preference* OR AB preference*) OR (TI choice* OR AB choice*) OR (TI pattern* OR AB pattern*))) OR ((TI “Food secur*” OR AB “Food secur*”) OR (TI “food insecur*” OR AB “food insecur*”))) OR (MM “Food preferences”))) | 253 |

| PsycInfo | ((((title: (Aborigin*)) OR (title: (“torres strait island*”)) OR (title: (Indigen*)) OR (title: (“first natio*”)) OR (title: (Maori)) OR (title: (Aotearoa)) OR (title: (“first people*”)) OR (title: (“native people*”)) OR (title: (“native born”)) OR (title: (Metis)) OR (title: (Inuit*)) OR (title: (“African America*”)) OR (title: (“Native America*”)) OR (title: (“American India*”)) OR (title: (Amerindian*)) OR (title: (Eskimo*)) OR (title: (“Native Canad*”)) OR (title: (“First America*”)) OR (title: (“Indigenous America*”)) OR (title: (Saami)) OR (title: (Sami)) OR (title: (Greenlandic*)) OR (title: (Nunavut*)) OR (title: (“first Australia*”)) OR (title: (“Alaska Native*”)) OR (title: (“Alaskan Native*”)) OR (title: (“Native Hawaiian*”)) OR (title: (natives))) OR ((abstract: (Aborigin*)) OR (abstract: (“torres strait island*”)) OR (abstract: (Indigen*)) OR (abstract: (“first natio*”)) OR (abstract: (Maori)) OR (abstract: (Aotearoa)) OR (abstract: (“first people*”)) OR (abstract: (“native people*”)) OR (abstract: (“native born”)) OR (abstract: (Metis)) OR (abstract: (Inuit*)) OR (abstract: (“African America*”)) OR (abstract: (“Native America*”)) OR (abstract: (“American India*”)) OR (abstract: (Amerindian*)) OR (abstract: (Eskimo*)) OR (abstract: (“Native Canad*”)) OR (abstract: (“First America*”)) OR (abstract: (“Indigenous America*”)) OR (abstract: (Saami)) OR (abstract: (Sami)) OR (abstract: (Greenlandic*)) OR (abstract: (Nunavut*)) OR (abstract: (“first Australia*”)) OR (abstract: (“Alaska Native*”)) OR (abstract: (“Alaskan Native*”)) OR (abstract: (“Native Hawaiian*”)) OR (abstract: (natives)))) OR (((IndexTermsFilt: (“American Indians”)) OR (IndexTermsFilt: (“Alaska Natives”)) OR (IndexTermsFilt: (“Hawaii Natives”)) OR (IndexTermsFilt: (“Indigenous Populations”))))) AND ((title: (Remote) OR title: (Isolated) OR title: (rural) OR title: (secluded) OR title: (regional)) OR (abstract: (Remote) OR abstract: (Isolated) OR abstract: (rural) OR abstract: (secluded) OR abstract: (regional))) AND ((((((title: (soft))) OR ((title: (sugar*))) OR ((title: (fizzy))) OR ((title: (energy))) OR ((title: (carbonated))) OR ((title: (discretionary))) OR ((title: (“sucrose sweetened”))) OR ((title: (sucrose-sweetened))) OR ((title: (“sugar sweetened”))) OR ((title: (sugar-sweetened)))) NEAR/3 (((title: (beverage*))) OR ((title: (drink*)))) OR (((abstract: (soft))) OR ((abstract: (sugar*))) OR ((abstract: (fizzy))) OR ((abstract: (energy))) OR ((abstract: (carbonated))) OR ((abstract: (discretionary))) OR ((abstract: (“sucrose sweetened”))) OR ((abstract: (sucrose-sweetened))) ((abstract: (“sugar sweetened”))) OR ((abstract: (sugar-sweetened)))) NEAR/3 (((abstract: (beverage*))) OR ((abstract: (drink*))))) OR ((((title: (cordial*))) OR ((title: (juice*))) OR ((title: (soda*))) OR ((title: (“coca cola”))) OR ((title: (coke))) OR ((title: (softdrink*)))) OR (((abstract: (cordial*))) OR ((abstract: (juice*))) OR ((abstract: (soda*))) OR ((abstract: (“coca cola”))) OR ((abstract: (coke))) OR ((abstract: (softdrink*)))))) OR (((((title: (diet*))) OR ((title: (food*))) OR ((title: (drink*)))) NEAR/3 (((title: (qualit*))) OR ((title: (preference*))) OR ((title: (choice*))) OR ((title: (pattern*)))) OR (((abstract: (diet*))) OR ((abstract: (food*))) OR ((abstract: (drink*)))) NEAR/3 (((abstract: (qualit*))) OR ((abstract: (preference*))) OR ((abstract: (choice*))) OR ((abstract: (pattern*))))) OR ((((title: (“Food secur*”))) OR ((title: (“food insecur*”)))) OR (((abstract: (“Food secur*”))) OR ((abstract: (“food insecur*”))))) OR ((((IndexTermsFilt: (“Food Preferences”))))))) | 138 |

| Web of Science | (TI = (Aborigin* OR “torres strait island*” OR Indigen* OR “first natio*” OR Maori OR Aotearoa OR “first people*” OR “native people*” OR “native born” OR Metis OR Inuit* OR “African America*” OR “Native America*” OR “American India*” OR Amerindian* OR Eskimo* OR “Native Canad*” OR “First America*” OR “Indigenous America*” OR Saami OR Sami OR Greenlandic* OR Nunavut* OR “first Australia*” OR “Alaska Native*” OR “Alaskan Native*” OR “Native Hawaiian*” OR natives OR “American Indians or Alaska Natives” OR “Indigenous Canadians” OR “Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander”) OR AB = (Aborigin* OR “torres strait island*” OR Indigen* OR “first natio*” OR Maori OR Aotearoa OR “first people*” OR “native people*” OR “native born” OR Metis OR Inuit* OR “African America*” OR “Native America*” OR “American India*” OR Amerindian* OR Eskimo* OR “Native Canad*” OR “First America*” OR “Indigenous America*” OR Saami OR Sami OR Greenlandic* OR Nunavut* OR “first Australia*” OR “Alaska Native*” OR “Alaskan Native*” OR “Native Hawaiian*” OR natives OR “American Indians or Alaska Natives” OR “Indigenous Canadians” OR “Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander”)) AND (TI = (Remote OR Isolated OR rural OR secluded OR regional OR “Rural Population”) OR AB = (Remote OR Isolated OR rural OR secluded OR regional OR “Rural Population”)) AND ((TI = (((((soft OR sugar* OR fizzy OR energy OR carbonated OR discretionary OR “sugar sweetened” OR sugar-sweetened OR “sucrose sweetened” OR sucrose-sweetened) NEAR/3 (beverage* OR drink*)) OR (cordial* OR juice* OR soda* OR “coca cola” OR coke OR softdrink*)) OR “Sugar-Sweetened Beverages” OR ((((Diet* OR food* OR drink*) NEAR/3 (qualit* OR preference* OR choice* OR pattern*)) OR (“Food secur*” OR “food insecur*”)) OR “Food preferences”)))) OR AB = (((((soft OR sugar* OR fizzy OR energy OR carbonated OR discretionary OR “sugar sweetened” OR sugar-sweetened OR “sucrose sweetened” OR sucrose-sweetened) NEAR/3 (beverage* OR drink*)) OR (cordial* OR juice* OR soda* OR “coca cola” OR coke OR softdrink*)) OR “Sugar-Sweetened Beverages” OR ((((Diet* OR food* OR drink*) NEAR/3 (qualit* OR preference* OR choice* OR pattern*)) OR (“Food secur*” OR “food insecur*”)) OR “Food preferences”)))) | 1087 |

| Ovid Medline | ((Aborigin* or “torres strait island*” or Indigen* or “first natio*” or Maori or Aotearoa or “first people*” or “native people*” or “native born” or Metis or Inuit* or “African America*” or “Native America*” or “American India*” or Amerindian* or Eskimo* or “Native Canad*” or “First America*” or “Indigenous America*” or Saami or Sami or Greenlandic* or Nunavut* or “first Australia*” or “Alaska Native*” or “Alaskan Native*” or “Native Hawaiian*” or natives).tw. or exp “American Indians or Alaska Natives”/ or exp “Indigenous Canadians”/ or exp “Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander”/) and ((Remote or Isolated or rural or secluded or regional).tw. or exp “Rural Population”/) and ((((soft or sugar* or fizzy or energy or carbonated or discretionary or “sugar sweetened” or sugar-sweetened or “sucrose sweetened” or sucrose-sweetened) adj3 (beverage* or drink*)) or (cordial* or juice* or soda* or “coca cola” or coke or softdrink*)).tw. or exp “Sugar-Sweetened Beverages”/ or ((((Diet* or food* or drink*) adj3 (qualit* or preference* or choice* or pattern*)) or (“Food secur*” or “food insecur*”)).tw. or exp “Food preferences”/)) | 481 |

| S1 | S2 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 4.1 | 4.2 | 4.3 | 4.4 | 4.5 | 5.1 | 5.2 | 5.3 | 5.4 | 5.5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bailie et al. [34] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||||||||||

| Brimblecombe et al. [35] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||||||||||

| Byker Shanks et al. [36] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||||||||||

| Chakona et al. [37] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||||||||||

| Colles et al. [38] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||||||||||

| Dimitropoulos et al. [39] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||||||||||

| Elwan et al. [40] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||||||||||

| Frank et al. [41] | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | ||||||||||

| Galloway et al. [42] | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | ||||||||||

| Godrich et al. [43] | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||||||||||

| Hall et al. [44] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||||||||||

| Johnson-Down et al. [45] | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | ||||||||||

| Kirkham et al. [46] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||||||||||

| Koller et al. [47] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||||||||||

| Kruske et al. [48] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||||||||||

| Kurschner et al. [49] | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | ||||||||||

| Kyoon-Achan et al. [50] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||||||||||

| Levin et al. [51] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||||||||||

| Lindsay et al. [52] | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||||||||||

| Myers et al. [53] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||||||||||

| Patel et al. [54] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||||||||||

| Pollard et al. [55] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||||||||||

| Sarkar et al. [56] | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | ||||||||||

| Seear et al. [57] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||||||||||

| Thurber et al. [58] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | ||||||||||

| Thurber et al. [59] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | ||||||||||

| Tomayko et al. [60] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||||||||||

| Tonkin et al. [61] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | ||||||||||

| Walch et al. [62] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||||||||||

| Walch et al. [63] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||||||||||

| Wattelez et al. [64] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | ||||||||||

| Wood et al. [65] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||||||||||

| Wycherley et al. [66] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | ||||||||||

| Zoellner et al. [67] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Screening | |

|---|---|

| S1 | Are there clear research questions? |

| S2 | Do the collected data allow to address the research questions? |

| Qualitative | |

| 1.1 | Is the qualitative approach appropriate to answer the research question? |

| 1.2 | Are the qualitative data collection methods adequate to address the research question? |

| 1.3 | Are the findings adequately derived from the data? |

| 1.4 | Is the interpretation of results sufficiently substantiated by data? |

| 1.5 | Is there coherence between qualitative data sources, collection, analysis, and interpretation? |

| Quantitative Descriptive | |

| 4.1 | Is the sampling strategy relevant to address the research question? |

| 4.2 | Is the sample representative of the target population? |

| 4.3 | Are the measurements appropriate? |

| 4.4 | Is the risk of nonresponse bias low? |

| 4.5 | Is the statistical analysis appropriate to answer the research question? |

| Mixed methods | |

| 5.1 | Is there an adequate rationale for using a mixed methods design to address the research question? |

| 5.2 | Are the different components of the study effectively integrated to answer the research question? |

| 5.3 | Are the outputs of the integration of qualitative and quantitative components adequately interpreted? |

| 5.4 | Are divergences and inconsistencies between quantitative and qualitative results adequately addressed? |

| 5.5 | Do the different components of the study adhere to the quality criteria of each tradition of the methods involved? |

| Author | Year Published | Study Location | Study Title | Study Aim | Study Design: Method | Study Quality 1 | Number of Participants | Participant Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bailie et al. [34] | 2004 | QLD, SA, NSW, NT, WA Tasmania, Victoria, Australia | Water supply and sanitation in remote Indigenous communities–priorities for health development | To review survey data on water supply and sanitation in remote Indigenous communities over the past 10 years, and to discuss the significance of the findings in terms of their contribution to the available information and in terms of informing priorities for health development. | Quantitative: surveys | Strong | N/A–2 pre-existing survey results used | N/A–Community Housing and Infrastructure Needs Survey (QLD, SA, NSW, NT, WA Tasmania, Victoria), Environmental Health Survey (NT) |

| Brimblecombe et al. [35] | 2014 | NT, Australia | Factors Influencing Food Choice in an Australian Aboriginal Community | To build a deeper understanding of the meaning of the traditional Aboriginal diet and the contemporary food supply through people’s views and experiences in relation to food-related knowledge, attitudes, and choice. | Qualitative: semi-structured interviews and focus groups | Strong | 46 people (12 from individual interviews, 34 from focus groups) | All adults, 67% individual interviews male, 6 focus groups with family members, 2 with health centre staff |

| Byker Shanks et al. [36] | 2020 | Montana, USA | Perceptions of food environments and nutrition among residents of the Flathead Indian Reservation | To investigate food environments and diets among Flathead Reservation residents to inform programs, policy, and practice around food and nutrition in the future. | Mixed methods: Qualitative semi-structured interviews, Quantitative surveys | Strong | 80 people (80 from surveys, 76 from interviews) | All participants identified as household decision makers, 78% female, 82% graduated high school, mean age 40 years, 81% no children |

| Chakona et al. [37] | 2020 | Eastern Cape province, South Africa | Social circumstances and cultural beliefs influence maternal nutrition, breastfeeding and child feeding practices in South Africa | To gather information on infant care giving practices including breastfeeding, children’s diets, maternal and child dietary diversity and household socio-economic characteristics. | Mixed methods: Qualitative focus groups Quantitative: surveys | Strong | 178 caregiver/child pairs (84 from surveys, 94 from focus groups) | Surveys: mean age of 34.7 years for mothers/caregivers and 16.3 months for children, 48 pairs were mother–child whilst 36 were caregiver–child pairs which included 21 grandmothers and the other 15 pairs were other female family members. Focus groups: 43 Mothers and 51 grandmothers, majority of which had informal employment, 6 participants <20 years, 24 participants 20–30 years, 26 participants 31–50 years, 38 participants >50 years, from 9 different communities |

| Colles et al. [38] | 2014 | NT, Australia | Food, food choice and nutrition promotion in a remote Australian Aboriginal community | To explore strategies to provide culturally sensitive information and approaches to support food choice and health among residents of a remote Aboriginal community. | Qualitative: semi-structured interviews | Strong | 30 people | Adults aged 18–61 years, 70% female, mean age 42.9 years, number of people in each participants household ranges from 3 to 20, with an average of 9.3 people. |

| Dimitropoulos et al. [39] | 2018 | NSW, Australia | A collaboration with local Aboriginal communities in rural New South Wales, Australia to determine the oral health needs of their children and develop a community-owned oral health promotion program | To collaborate with local Aboriginal communities to determine the oral health needs of Aboriginal children aged 5–12 years, the oral health knowledge, and attitudes towards oral health of parents/guardians, and the perceived barriers and enablers towards oral health promotion for school children by local school staff and community health workers. | Quantitative: surveys | Strong | 149 people | Children survey: 78 children aged 5–12 years enrolled in local schools, 56% female Caregiver survey: 32 parents/guardians, 88% female Staff survey: 37 School staff/Health workers employed in local schools and community centres–3 school principals, 19 teachers, 4 administration staff, 11 education officers |

| Elwan et al. [40] | 2015 | Rural Athabascan community, 200 miles west of Fairbanks, Alaska, USA | Beverage consumption in an Alaska Native village: a mixed-methods study of behaviour, attitudes, and access | To assess the frequency of SSB, water and milk consumption, ascertain the attitudes towards consumption of water, milk and SSB of residents of a rural, Interior Alaska Native (Athasbascan) community, and assess rural access to water, milk and SSBs. | Mixed methods: Quantitative: survey and shop inventory Qualitative–focus groups and individual interviews | Strong | 95 people (67 from surveys, 21 from focus groups, 7 from interviews) and 3 shops | Survey: 25 adults (76% female), 21 adolescents (48% female), and 21 children (48% female) Interviews: Head Start and Early Head Start program instructors and shop owners Focus groups: community members Shops: located in the village |

| Frank et al. [41] | 2016 | Yucatan, Mexico | Two approaches, one problem: Cultural constructions of type II diabetes in an indigenous community in Yucatán, Mexico | To understand how diabetes is understood and treated in Indigenous settings in rural Yucatán. | Qualitative: semi-structured interviews | Moderate-strong | 36 people | 34 community members (74% female, aged from 33 to 38 years, 71% had T2DM), 2 clinicians employed in health care facility |

| Galloway et al. [42] | 2015 | Inuvialuit, Nunavut, and Nunatsiavut Regions, North Canada | Socioeconomic and Cultural Correlates of Diet Quality in the Canadian Arctic: Results from the 2007–2008 Inuit Health Survey | To increase understanding of the factors influencing nutrition and health outcomes in Inuit communities so that the many positive aspects of Inuit nutrition can operate unconstrained by socioeconomic and institutional barriers. | Quantitative: survey | Moderate | 2097 people | All Inuit residents, 26% aged 19–30 yo, 47% aged 31–50 years, 27% aged 51+ years, 62% women, 40% employed |

| Godrich et al. [43] | 2017 | WA, Australia | What are the determinants of food security among regional and remote Western Australian children? | To explore the impact of food security determinants on children in regional and remote WA, across food availability, access, and utilisation dimensions. | Qualitative: semi-structured interviews | Moderate-strong | 20 people | 8 health workers, 6 school/youth workers, 6 food supply workers, 80% female |

| Hall et al. [44] | 2019 | NT, QLD, NSW, and SA, Australia | Challenges of WASH in remote Australian Indigenous communities | To identify the status of water, sanitation, and hygiene services within remote communities on mainland Australia. | Qualitative: open-ended interviews | Strong | 16 people | 6 state representatives, 4 Indigenous representatives, 3 research representatives, 2 utility representatives, 2 NGO representatives |

| Johnson-Down et al. [45] | 2012 | Northern Quebec, Canada | How is nutrition transition affecting dietary adequacy in Eeyouch (Cree) adults of Northern Quebec, Canada? | To evaluate TF intake for its importance in Cree communities and characterise the nutrient intake and dietary adequacy of adults in this population, as well as look at the impact of TF on dietary adequacy. | Quantitative: surveys | Moderate | 850 people | 59% women, average age of 40.9 years, age range of 19–91 years, 48% current smokers |

| Kirkham et al. [46] | 2020 | NT, Australia | ‘No sugar’, ‘no junk food’, ‘do more exercise’–moving beyond simple messages to improve the health of Aboriginal women with Hyperglycaemia in Pregnancy in the Northern Territory–A phenomenological study | To explore Aboriginal women’s experiences of hyperglycaemia in pregnancy, associated health care, and their understandings of the condition and health behaviours, to better understand women’s specific needs and inform future systems change. | Qualitative: semi-structured interviews | Strong | 42 people | 35 Aboriginal women (age spanning 21–44 years, 2 pregnant, 33 post-partum, 10 with T2DM and 25 who had GDM), 7 Health professionals across NT (100% female) |

| Koller et al. [47] | 2021 | Yukon-Kuskowim region, Western Alaska, USA | Storekeeper perspectives on improving dietary intake in 12 rural remote western Alaska communities: the “Got Neqpiaq?” project | To update and increase understanding of why fruit and vegetable intake remains low and SSB consumption continues to be high despite years of recommended changes by health care providers, nutritionists, and public health professionals. | Qualitative: semi-structured interviews | Strong | 22 people | 100% storekeepers, from 12 different communities |

| Kruske et al. [48] | 2012 | NT, Australia | Growing Up Our Way: The First Year of Life in Remote Aboriginal Australia | To better inform Western-educated health professionals working in remote communities on how to incorporate an Aboriginal-centred perspective in their work associated with infant development, parenting, and child-rearing practices by collecting Aboriginal families’ stories about child rearing, development, behaviour, health, and well-being. | Qualitative: semi-structured interviews every 4–6 weeks for 1 year | Strong | 15 mothers and any family members present at time of interview | 100% female, 100% pregnant, aged between 15 and 29 years, 93% had male partners, 40% were first time mothers, 60% had 2–4 children |

| Kurschner et al. [49] | 2019 | Tecpan, Chimaltenango, Guatemala | Impact of school and work status on diet and physical activity in rural Guatemalan adolescent girls: a qualitative study | To address the impact of out-of-school status on diet and physical activity by conducting a series of qualitative interviews with adolescent girls from one midsized, largely Indigenous Maya town. | Qualitative: semi-structured interviews | Moderate-strong | 20 people | 20% 15–16 years, 70% 17–18 years, 10% 19 years, 100% girls, 50% at school and unemployed, 10% at school and employed, 40% not at school and employed, 95% single, 25% have children, median household size is 6 people |

| Kyoon-Achan et al. [50] | 2021 | Manitoba, Canada | First Nations and Metis peoples’ access and equity challenges with early childhood oral health: a qualitative study | To report the challenges and problems faced by First Nations and Metis parents in meeting the early childhood oral health needs of their children and to offer context-based and community informed recommendations on improving oral healthcare equity and outcomes in First Nations and Metis communities in Manitoba. | Qualitative: focus groups | Strong | 59 people | 18.4% male, 88% had children, age range from 21 to 71 years, 44% employed, 50% married or living in common-law relationships |

| Levin et al. [51] | 2017 | Pueblo Kichwa, Rukullakta, Ecuador | Maintaining Traditions: A Qualitative Study of Early Childhood Caries Risk and Protective Factors in an Indigenous Community | To identify the risk factors and protective factors for nutrition and oral health among Kichwa families participating in a community-based oral health and nutrition intervention. | Qualitative: semi-structured interviews | Strong | 18 caregiver/child pairs | Parent/caregiver commenting on their child. Child mean age was 4.1 years, age range was 6 months-6 years, 56% male, average of 6.4 decayed teeth. No information on parents provided. |

| Lindsay et al. [52] | 2008 | Ceara State, North-East Brazil | Brazilian mothers’ beliefs, attitudes and practices related to child weight status and early feeding within the context of nutrition transition | To describe mothers’ child feeding practices and perceptions of how these factors might be associated with child weight status, including underweight and the development of childhood overweight, to explore the role of socioeconomic, cultural, and organisational factors on these relationships; and to identify potential barriers that mothers in this population face to making healthy feeding choices for their children. | Qualitative: focus groups | Moderate-strong | 41 people | 100% mothers, 75% married, age range of 19–49 years, have 4 children on average |

| Myers et al. [53] | 2014 | Victoria, Australia | Early childhood nutrition concerns, resources, and services for Aboriginal families in Victoria | To investigate the child nutrition concerns of Aboriginal families with young children attending Aboriginal health and early childhood services in Victoria, training needs of early childhood practitioners, and sources of nutrition and child health information and advice for Aboriginal families with young children. | Qualitative: focus groups and semi-structured interviews | Strong | 80 people (35 from focus groups, 45 from interviews) | Focus groups: parents of children aged 0–8 years, 63% male Interviews: health and children’s services practitioners, “mostly female”, 44% Aboriginal health workers |

| Patel et al. [54] | 2021 | Kimberley, WA, Australia | Oral health education and prevention strategies among remote Aboriginal communities: a qualitative study | To investigate the perceptions and attitudes of oral health among Aboriginal Australians living in remote Kimberley communities in the context of better understanding existing and informing future prevention and education strategies. | Qualitative: interviews and focus groups | Strong | 103 people (23 from interviews, 80 from focus groups) | Adults over 18 years, 66% females |

| Pollard et al. [55] | 2014 | WA, Australia | Understanding food security issues in remote Western Australian Indigenous communities | To determine store managers’ perceptions of the extent of food insecurity in their communities, key concerns relating to food in remote stores, store operations, infrastructure, and resource needs. | Qualitative: telephone semi-structured interview | Strong | 33 people | 100% remote community store managers |

| Sarkar et al. [56] | 2015 | Labrador, Canada | Water insecurity in Canadian Indigenous communities: some inconvenient truths | To determine the water insecurity of a remote Indigenous community and their coping strategies and to find their associated health risks. | Mixed methods; Qualitative: open-ended interviews and focus groups Quantitative: water quality testing | Moderate | 48 people (43 from focus groups, 5 from interviews) 4 water samples | 4 Focus groups: women’s group, high school students, community members, and community leaders Interviews: community leader, woman, community nurse, teacher, elder Water samples: wells, brooks, ponds, and public water |

| Seear et al. [57] | 2020 | Derby, WA, Australia | Maboo wirriya, be healthy: Community-directed development of an evidence-based diabetes prevention program for young Aboriginal people in a remote Australian town | To discover what type of prevention program would be suitable for young Aboriginal people in and around Derby; utilise community knowledge and previous research evidence to design a preliminary lifestyle modification program consistent with community preferences; and refine the program after testing in a small exploratory pilot. | Qualitative: focus groups | Strong | 32 people | 75% female, 47% participants aged 16–17 years, 13% aged 18–25 years, 41% aged from 26 to 45 years |

| Thurber et al. [58] | 2014 | 11 diverse locations across Australia | Social determinants of sugar-sweetened beverage consumption in the Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children | Using data from the fourth wave of the Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children, this cross-sectional study uses multilevel modelling to examine the association between sugar-sweetened beverage consumption and an array of social, cultural, and environmental factors, including area-level influences. | Quantitative: survey | Moderate | 1283 caregiver/child pairs | Parent/caregiver reporting on their child. Children aged 3–9 years |

| Thurber et al. [59] | 2018 | 11 diverse locations across Australia | Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption among Indigenous Australian children aged 0–3 years and association with sociodemographic, life circumstances and health factors | To explore beverage intake and associations between sugar-sweetened beverage intake and sociodemographic, life circumstances, health, and well-being factors in a national cohort of Indigenous children. | Mixed methods: Quantitative: survey Qualitative: focus groups | Moderate-strong | 938 people (933 from surveys, 5 from focus groups) | Survey: Parent/caregiver reporting on their child. Children 0–3 years, 51% male, 30% aged 0–12 months, 42% aged 12–18 months, and 28% 18–36 months old. Focus groups: Research Administration Officers, 100% Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander, most live in the area in which they conduct interviews |

| Tomayko et al. [60] | 2017 | 5 communities across USA | Household food insecurity and dietary patterns in rural and urban American Indian families with young children | To evaluate the prevalence of food insecurity among American Indian households from both rural and urban communities and examine the association of food insecurity with diet patterns of both adults and young children (2–5 years) concurrently in these households. | Mixed methods; Quantitative: survey Qualitative–focus groups | Strong | 481 caregiver/child pairs (450 from surveys, 31 from focus groups) | Survey: 53% rural households, 61% food insecure, 100% adult caregiver (95% female, average age 31.5 years), of child (average age 45 months old, 50% female) 6 Focus groups: adults from families who had completed the Healthy Children Strong Families 2 intervention |

| Tonkin et al. [61] | 2017 | NT, Australia | A Smartphone App to Reduce Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Consumption Among Young Adults in Australian Remote Indigenous Communities: Design, Formative Evaluation and User-Testing | To consult RIC members to inform the content of a smartphone app that can be used to monitor and reduce sugar-sweetened beverage intake in RICs. | Mixed method; Qualitative: semi-structured interviews (F and E), “think aloud shop” (F and E) Quantitative–survey (F) | Moderate-strong | 36 people (20 from formative research phase, 16 new participants and 4 repeated participants in end-user testing phase) | Formative research: 50% female, 55% under 25 years, age range from 18 to 35 years End-user testing: 55% female, 25% under 25 years, age range from 21 to 35 years |

| Walch et al. [62] | 2022 | Yukon-Kuskokwim region, South-West Alaska, USA | Impact of Assistance Programs on Indigenous Ways of Life in 12 Rural Remote Western Alaska Native Communities: Elder Perspectives Shared in Formative Work for the “Got Neqpiaq?” Project | To share perspectives of Alaska Native Elders that identify the benefits of, and encourage, careful consideration of the impact of government-sponsored food, nutrition, and childcare assistance programmes on Indigenous cultures and traditional ways of life. | Qualitative: focus groups | Strong | 66 people | 55% female, 100% community elders |

| Walch et al. [63] | 2021 | Yukon-Kuskokwim region, South-West Alaska, USA | Alaska Native Elders’ perspectives on dietary patterns in rural, remote communities | To enhance the local and regional relevance to design, implement, and evaluate an obesity prevention effort, the objective of this study was to listen to Yup’ik and Cup’ik Elders to better understand their views on maintaining a healthy diet, physical activities, and traditional values to inform obesity prevention efforts. | Qualitative: focus groups | Strong | 66 people | 55% female, 100% community elders |

| Wattelez et al. [64] | 2019 | New Caledonia | Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Consumption and Associated Factors in School-Going Adolescents of New Caledonia | To broaden the vision on health among the 11–16 years adolescents in New Caledonia by assessing their SSB consumption behaviours and the associations with individual and socio-environmental factors. | Quantitative: survey | Moderate-strong | 447 people | Adolescents 11–16 years, 57% female, 81% rural, 46% low SES |

| Wood et al. [65] | 2021 | NT, Australia | Incorporating Aboriginal women’s voices in improving care and reducing risk for women with diabetes in pregnancy–A phenomenological study | To explore Aboriginal women’s and health providers’ preferences for a program to prevent and improve diabetes after pregnancy. | Qualitative: semi-structured interviews | Strong | 22 people | 11 Aboriginal women with a history of GDM or T2DM in the last 5 years, aged >18 years, 7 health professionals, 4 community advocates |

| Wycherley et al. [66] | 2019 | NT, Australia | Associations between Community Environmental-Level Factors and Diet Quality in Geographically Isolated Australian Communities | To conduct a descriptive analysis to explore modifiable environmental-level factors that are associated with the features of dietary intake that underpin cardio-metabolic disease risk in geographically isolated Indigenous Australian communities. | Quantitative: point-of-sale data | Moderate-strong | N/A–2 pre-existing study results used | N/A –the Stores Healthy Options Project in Remote Indigenous Communities (SHOP@RIC) study and the Environments and Remote Indigenous Cardio-Metabolic Health Project (EnRICH) |

| Zoellner et al. [67] | 2011 | Lower Mississippi Delta, USA | Health literacy is associated with healthy eating index scores and sugar-sweetened beverage intake: findings from the rural Lower Mississippi Delta | To evaluate health literacy skills in relation to Healthy Eating Index scores and SSB consumption while accounting for demographic variables. | Quantitative: survey | Strong | 376 people | 76% female, aged 18–84 years |

| Author | Quotes | Other Comments | Summarised Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brimblecombe et al. [35] |

|

| Exposure to food promotion–Advertising Environment food availability and accessibility- Community availability Cultural cognitions–Autonomy Food knowledge, skills, and abilities–Health literacy Situational and time constraints–Convenience Sensory perception–Taste preferences |

| Colles et al. [38] | In response to the question, “if you are in the store and your child/children/grandchildren is/are crying ‘I want, I want’ for coke or lollies, what do you do?”

|

| Parent feeding style–used as incentive Food knowledge, skills, and abilities–Health literacy Cultural cognitions–Autonomy Social influence–presence of others Household SES–parent education level Sensory perception–Taste preferences |

| Frank et al. [41] |

|

| Cultural cognitions–traditional knowledge Sensory perception–Taste preferences Home food availability and accessibility–Household availability Environment food availability and accessibility–Community availability Biological demographics–gender Cultural cognitions–Autonomy Food Habits–Familiarity Food knowledge, skills, and abilities–Health literacy |

| Godrich et al. [43] |

|

| Exposure to food promotion–Advertising Government regulations–Store owner decisions |

| Hall [44] |

|

| Characteristics of living area–water quality Sensory perception–Taste preferences |

| Kirkham et al. [46] |

|

| Food knowledge, skills, and abilities–Health literacy Sensory perception–Taste preferences |

| Koller et al. [47] |

|

| Biological demographics–age Natural conditions- weather Food Habits–Familiarity Sensory perception–Taste preferences Market prices–Affordability Environment food availability and accessibility–Community availability Parental behaviours–parent role modelling Government regulations–Store owner decisions Cultural cognitions–Autonomy |

| Kruske et al. [48] |

|

| Parent feeding style–used as incentive |

| Kurschner et al. [49] |

|

| Situational and time constraints–Convenience Environment food availability and accessibility–Community availability |

| Kyoon-Achan et al. [50] |

|

| Food knowledge, skills, and abilities–Health literacy Environment food availability and accessibility–Community availability Parent feeding style–used as incentive Parental resources and risk factors- time constraints |

| Levin et al. [51] |

|

| Environment food availability and accessibility–Community availability Market prices–Affordability Sensory perception–Taste preferences Characteristics of living area- water quality Food knowledge, skills, and abilities–Health literacy Parent feeding style–used as incentive Situational and time constraints–Convenience Cultural cognitions–traditional knowledge |

| Lindsay et al. [52] |

|

| Household SES–parental income |

| Myers et al. [53] |

|

| Food knowledge, skills, and abilities–Health literacy Parent feeding style–used as incentive Sensory perception- Taste preferences Campaigns–Lack of policy |

| Patel et al. [54] |

|

| Environment food availability and accessibility–Community availability Sensory perception- Taste preferences Government regulation–Exploitation of small communities Market prices- Affordability Parent feeding style–used as incentive Exposure to food promotion- Advertising Cultural cognitions–traditional knowledge Government regulation–Store owner decisions |

| Pollard et al. [55] |

|

| Sensory perception–Taste preferences |

| Seear et al. [57] |

|

| Environment food availability and accessibility–Community availability Exposure to food promotion–Advertising Cultural cognitions–Autonomy Biological demographics–age Sensory perception–Taste preferences |

| Walch et al. [62] |

|

| Environment food availability and accessibility–Community availability Cultural cognitions–traditional knowledge |

| Walch et al. [63] |

|

| Sensory perception–Taste preferences Government regulations–Store owner decisions Environment food availability and accessibility–Community availability Cultural cognitions –traditional knowledge Situational and time constraints–Convenience Market prices–Affordability Parent feeding style–used as incentive Cultural cognitions–Autonomy Food habits–familiarity |

| Wood et al. [65] |

|

| Sensory perception- Taste preferences Cultural cognitions–Autonomy Environment food availability and accessibility- Community availability Market prices–Affordability Cultural cognitions–traditional knowledge Characteristics of living area- living environment |

| Author | Quotes | Other Comments | Summarised Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Byker Shanks et al. [36] |

|

| Environment food availability and accessibility–Community availability |

| Chakona [37] |

|

| Market prices–Affordability Parental attitudes and beliefs–priorities Sensory perception–Taste preferences Food knowledge, skills, and abilities–Health literacy |

| Elwan et al. [40] |

|

| Biological demographics–Age Food knowledge, skills, and abilities–Health literacy Cultural cognitions–Autonomy Government regulations–Store owner decisions Market prices–Affordability Environment food availability and accessibility–Community availability Sensory perception- Taste preferences Social influence–presence of others |

| Sarkar et al. [56] |

|

| Sensory perception–Taste preferences Market prices–Affordability Environment food availability and accessibility–Community availability Characteristics of living area–water quality Biological demographics–age Natural conditions- weather |

| Thurber et al. [59] |

|

| Biological demographics–age Family structure–Household size Parental resources and risk factors–Age of mother Parental resources and risk factors–parental social support Parental resources and risk factors–mother smoking status Parental resources and risk factors–prenatal catch-up attendance Household SES–parental income Household SES–parental employment status Parental attitudes and beliefs–priorities Characteristics of living area- water quality Natural conditions–weather Situational and Time Constraints–Stress Characteristics of living area–Access to health services |

| Tomayko et al. [60] |

|

| Household SES–Food security |

| Tonkin et al. [61] |

|

| Sensory perception–Taste preferences Food Habits–Familiarity Food knowledge, skills, and abilities–Health literacy |

| Author | Other Comments | Summarised Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Bailie et al. [34] |

| Characteristics of living area-water quality Sensory perception-Taste preferences |

| Dimitropoulos et al. [39] |

| Food knowledge, skills, and abilities–Health literacy Characteristics of living area–water quality |

| Galloway et al. [42] |

| Biological demographics–gender Biological demographics–age Cultural cognitions–traditional knowledge |

| Johnson-Down et al. [45] |

| Biological demographics–gender Biological demographics–age Cultural cognitions–traditional knowledge |

| Thurber et al. [58] |

| Cultural cognitions –traditional knowledge Family structure–Household size Household SES–parental income Household SES–parental employment status Household SES–parental education level Cultural cognitions–Autonomy Biological demographics–age |

| Wattelez et al. [64] |

| Characteristics of living area–living environment Food knowledge, skills, and abilities–Health literacy Personal SES–Income Environment food availability and accessibility–Community availability Characteristics of living area–water quality Sensory perception–Taste preferences |

| Wycherley et al. [66] |

| Family structure–Household size Personal SES–Employment status Characteristics of living area–area deprivation |

| Zoellner et al. [67] |

| Biological demographics–gender Biological demographics–age Food knowledge, skills, and abilities–Health literacy |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cartwright, J.; Netzel, M.E.; Sultanbawa, Y.; Wright, O.R.L. Seeking Sweetness: A Systematic Scoping Review of Factors Influencing Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Consumption in Remote Indigenous Communities Worldwide. Beverages 2023, 9, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages9010011

Cartwright J, Netzel ME, Sultanbawa Y, Wright ORL. Seeking Sweetness: A Systematic Scoping Review of Factors Influencing Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Consumption in Remote Indigenous Communities Worldwide. Beverages. 2023; 9(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages9010011

Chicago/Turabian StyleCartwright, Jessica, Michael E. Netzel, Yasmina Sultanbawa, and Olivia R. L. Wright. 2023. "Seeking Sweetness: A Systematic Scoping Review of Factors Influencing Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Consumption in Remote Indigenous Communities Worldwide" Beverages 9, no. 1: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages9010011

APA StyleCartwright, J., Netzel, M. E., Sultanbawa, Y., & Wright, O. R. L. (2023). Seeking Sweetness: A Systematic Scoping Review of Factors Influencing Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Consumption in Remote Indigenous Communities Worldwide. Beverages, 9(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages9010011