Properties of Water Activated with Low-Temperature Plasma in the Context of Microbial Activity

Abstract

1. Introduction

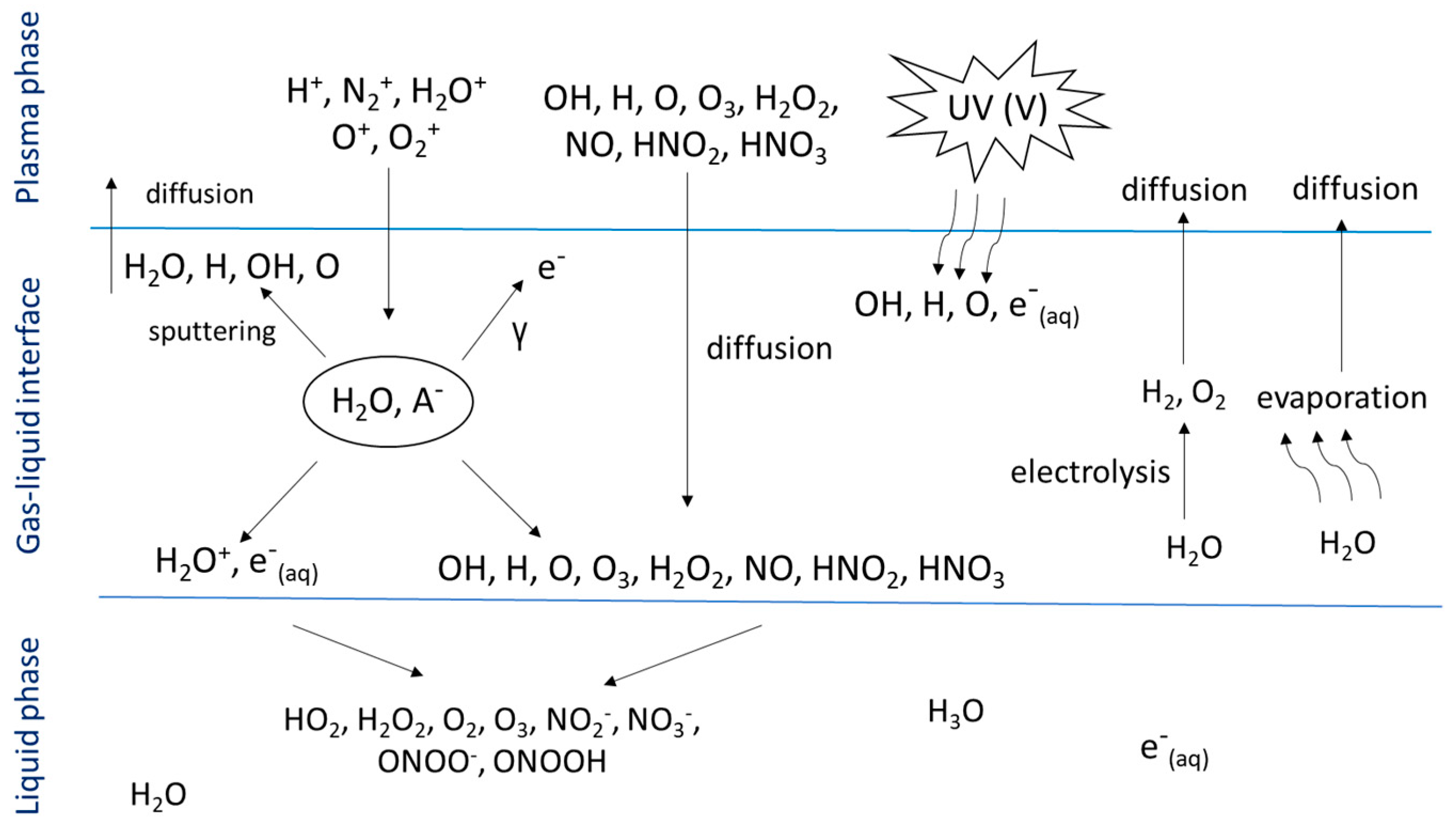

2. Generation of Plasma-Activated Water and Its Properties

2.1. pH

2.2. Oxidation-Reduction Potential

2.3. Conductivity

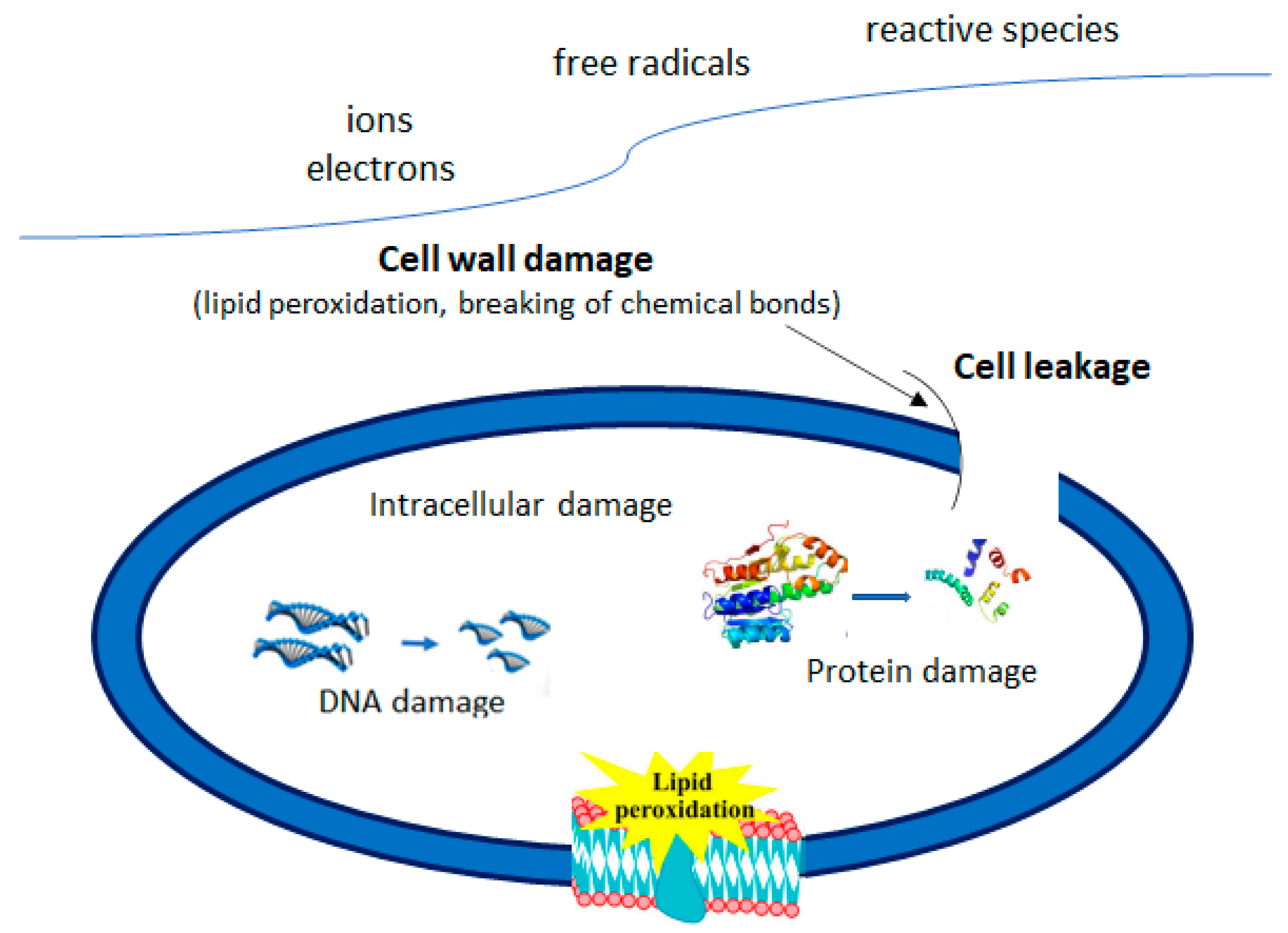

3. Influence of Plasma-Activated Water on Microorganisms

3.1. Role of Reactive Oxygen Species

3.2. Role of Reactive Nitrogen Species

4. The Role of Physiological Factors in the Inactivation of Microorganisms by PAW

5. The Use of Plasma-Activated Water in Inhibiting the Growth of Microorganisms

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bourke, P.; Ziuzina, D.; Han, L.; Cullen, P.J.; Gilmore, B.F. Microbiological interactions with cold plasma. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2017, 123, 308–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pater, A.; Zdaniewicz, M.; Satora, P. Application of water treated with low-temperature low-pressure glow plasma (LPGP) in various industries. Beverages 2022, 8, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogaerts, A.; Neyts, E.; Gijbels, R.; Mullen, J. Gas discharge plasmas and their applications. Spectrochim Acta Part B At. Spectrosc. 2002, 57, 609–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabares, F.L.; Junkar, I. Cold plasma systems and their application in surface treatments for medicine. Molecules 2021, 26, 1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanarro, I.; Herrero, V.J.; Carrasco, E.; Jiménez-Redondo, M. Cold plasma chemistry and diagnostics. Vacuum 2011, 85, 1120–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meichsner, J.; Schmidt, M.; Wagner, H.E. Non-Thermal Plasma Chemistry and Physics, 1st ed.; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2011; pp. 5–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nehra, V.; Kumar, A.; Dwivedi, H.K. Atmospheric non-thermal plasma sources. Int. J. Eng. 2008, 2, 53–68. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, L.; Shi, X.; Wu, X. Applications and challenges of low temperature plasma in pharmaceutical field. J. Pharm. Anal. 2021, 11, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kravets, L.I.; Gilman, A.B.; Dinescu, G. Modification of polymer membrane properties by low-temperature plasma. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2015, 85, 1284–1301. Available online: https://10.1134/S107036321505045X (accessed on 10 August 2022). [CrossRef]

- Kozáková, Z.; Krčma, F.; Čechová, L.; Simic, S.; Doskočil, L. Generation of silver nanoparticles by the pin-hole DC plasma source with and without gas bubbling. Plasma Phys. Technol. 2019, 6, 180–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G.; Kumar, D.; Kumar, A.; Al-Muhtaseb, A.H.; Pathania, D.; Naushad, M.; Mola, G.T. Revolution from monometallic to trimetallic nanoparticle composites, various synthesis methods and their applications: A review. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. 2017, 71, 1216–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, R.; Singh, A.; Singh, A.P. Recent developments in cold plasma decontamination technology in the food industry. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 80, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathod, N.B.; Ranveer, R.C.; Bhagwat, P.K.; Ozogul, F.; Benjakul, S.; Pillai, S.; Annapure, U.S. Cold plasma for the preservation of aquatic food products: An overview. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2021, 20, 4407–4425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozakova, Z.; Klimova, E.J.; Obradovic, B.M.; Dojcinovic, B.P.; Krcma, F.; Kuraica, M.M.; Olejnickova, Z.; Sykora, R.; Vavrova, M. Comparison of liquid and liquid-gas phase plasma reactors for discoloration of azodyes: Analysis of degradation products. Plasma Process. Polym. 2018, 15, 1700178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giardina, A.; Schiorlin, M.; Marotta, E.; Paradisi, C. Atmospheric pressure non-thermal plasma for air purification: Ions and ionic reactions induced by dc+ corona discharges in air contaminated with acetone and methanol. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 2020, 40, 1091–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konchekov, E.M.; Glinushkin, A.P.; Kalinitchenko, V.P.; Artem’ev, K.V.; Burmistrov, D.E.; Kozlov, V.A.; Kolik, L.V. Properties and use of water activated by plasma of piezoelectric direct discharge. Front. Phys. 2021, 8, 616385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, N.; Yasuoka, K. Review of plasma-based water treatment technologies for the decomposition of persistent organic compounds. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2020, 60, SA0801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukes, P.; Locke, B.R.; Brisset, J.L. Aqueous-Phase Chemistry of Electrical Discharge Plasma in Water and in Gas-Liquid Environments. In Plasma Chemistry and Catalysis in Gases and Liquids, 1st ed.; Parvulescu, V.I., Magureanu, M., Lukes, P., Eds.; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA: Weinheim, Germany, 2012; pp. 243–308. [Google Scholar]

- Bruggeman, P.J.; Kushner, M.J.; Locke, B.R.; Gardeniers, J.G.E.; Graham, W.G.; Graves, D.B.; Hofman-Caris, R.C.H.M.; Maric, D.; Reid, J.P.; Ceriani, E.; et al. Plasma–liquid interactions: A review and roadmap. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2016, 25, 053002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradu, C.; Kutasi, K.; Magureanu, M.; Puač, N.; Živković, S. Reactive nitrogen species in plasma-activated water: Generation, chemistry and application in agriculture. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2020, 53, 223001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Zhou, R.; Wang, P.; Xian, Y.; Mai-Prochnow, A.; Lu, X.; Cullen, P.J.; Ostrikov, K.; Bazaka, K. Plasma-activated water: Generation, origin of reactive species and biological applications. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2020, 53, 303001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirumdas, R.; Kothakota, A.; Annapure, U.; Siliveru, K.; Blundell, R.; Gatt, R.; Valdramidis, V.P. Plasma activated water (PAW): Chemistry, physico-chemical properties, applications in food and agriculture. Trends Food. Sci. Technol. 2018, 77, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamichhane, P.; Acharya, T.R.; Kaushik, N.; Nguyen, L.N.; Lim, J.S.; Hessel, V.; Kaushik, N.K.; Choi, E.H. Non-thermal argon plasma jets of various lengths for selective reactive oxygen and nitrogen species production. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 107782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Tian, Y.; Li, Y.; Ma, R.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Fang, J. Bactericidal effects against S. aureus and physicochemical properties of plasma activated water stored at different temperatures. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 28505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Ma, R.; Zhang, Q.; Feng, H.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Fang, J. Assessment of the physicochemical properties and biological effects of water activated by non-thermal plasma above and beneath the water surface. Plasma Process. Polym. 2015, 5, 439–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Wang, G.; Tian, Y.; Wang, K.; Zhang, J.; Fang, J. Non-thermal plasma-activated water inactivation of food-borne pathogen on fresh produce. J. Hazard. Mater. 2015, 300, 643–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Tian, Y.; Ma, R.; Liu, O.; Zhang, J. Effect of plasma activated water on the postharvest quality of button mushrooms, Agaricus bisporus. Food Chem. 2016, 197, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikawa, S.; Kitano, K.; Hamaguchi, S. Effects of pH on bacterial inactivation in aqueous solutions due to low-temperature atmospheric pressure plasma application. Plasma Process. Polym. 2010, 7, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlica, R.; Locke, B.R. Pulsed plasma gliding-arc discharges with water spray. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2008, 44, 482–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlica, R.; Grim, R.G.; Shih, K.Y.; Balkwill, D.; Locke, B.R. Bacteria inactivation using low power pulsed gliding arc discharges with water spray. Plasma Process. Polym. 2010, 7, 640–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traylor, M.J.; Pavlovich, M.; Karim, S.; Hait, P.; Sakiyama, Y.; Clark, D.; Graves, D. Long-term antibacterial efficacy of air plasma-activated water. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2011, 44, 472001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shainsky, N.; Dobrynin, D.; Ercan, U.; Joshi, S.G.; Ji, H.; Brooks, A.; Fridman, G.; Cho, Y.; Fridman, A.; Friedman, G. Retraction: Plasma acid: Water treated by dielectric barrier discharge. Plasma Process. Polym. 2012, 9, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Ma, R.; Tian, Y.; Su, B.; Wang, K.; Yu, S.; Zhang, J.; Fang, J. Sterilization efficiency of a novel electrochemical disinfectant against Staphylococcus aureus. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 3184–3192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pemen, A.J.M.; Hoeben, W.F.L.M.; Ooij, P.; Leenders, P.H.M. Plasma Activated Water. WO Patent No. WO2016096751, 23 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Abuzairi, T.; Ramadhanty, S.; Puspohadiningrum, D.F.; Ratnasari, A.; Poespawati, R.; Purnamaningsih, R.W. Investigation on physicochemical properties of plasma activated water for the application of medical device sterilization. AIP Conf. Proc. 2018, 1933, 040017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialopiotrowicz, T.; Ciesielski, W.; Domanski, J.; Doskocz, M.; Khachatryan, K.; Fiedorowicz, M.; Graz, K.; Koloczek, H.; Kozak, A.; Oszczeda, Z.; et al. Structure and physicochemical properties of water treated with low-temperature low-frequency glow plasma. Curr. Phys. Chem. 2016, 6, 312–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruggeman, P.; Leys, C. Non-thermal plasmas in and in contact with liquids. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2009, 42, 053001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Ma, R.; Zhu, M.; Du, M.; Zhang, H.; Jiao, Z. A systematic study of the antimicrobial mechanisms of cold atmospheric-pressure plasma for water disinfection. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 703, 134965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Qin, D.; Li, W.; Wu, F.; Li, L.; Liu, X. Inactivation of Penicillium italicum on kumquat via plasma-activated water and its effects on quality attributes. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2021, 343, 109090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brisset, J.L.; Benstaali, B.; Moussa, D.; Fanmoe, J.; Njoyim-Tamungang, E. Acidity control of plasma-chemical oxidation: Applications to dye removal, urban waste abatement and microbial inactivation. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2011, 20, 034021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai-Prochnow, A.; Zhou, R.; Zhang, T.; Ostrikov, K.K.; Mugunthan, S.; Rice, S.A.; Cullen, P.J. Interactions of plasma-activated water with biofilms: Inactivation, dispersal effects and mechanisms of action. Biofilms Microbiomes 2021, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamgang-Youbi, G.; Herry, J.M.; Meylheuc, T.; Brisset, J.L.; Bellon-Fontaine, M.N.; Doubla, A.; Naïtali, M. Microbial inactivation using plasma-activated water obtained by gliding electric discharges. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2009, 48, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Wang, J.; Xie, H.; Jiang, J.; Li, C.; Li, W.; Li, L.; Liu, X.; Lin, F. Inactivation effects of plasma-activated water on Fusarium graminearum. Food Control 2022, 134, 108683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.M.; Ojha, S.; Burgess, C.M.; Sun, D.W.; Tiwari, B.K. Inactivation efficacy and mechanisms of plasma activated water on bacteria in planktonic state. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2020, 129, 1248–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreau, M.; Orange, N.; Feuilloley, M.G. Non-thermal plasma technologies: New tools for bio-decontamination. Biotechnol. Adv. 2008, 26, 610–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russel, N.J.; Colley, M.; Simpson, R.K.; Trivett, A.J.; Evans, R.I. Mechanism of action of pulsed high electric field (PHEF) on the membranes of food-poisoning bacteria is an “all-or-nothing” effect. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2000, 55, 133–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Sun, P.; Bai, N.; Tian, Y.; Zhou, H.; Wei, S.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, J.; Fang, J. Inactivation of bacteria in an aqueous environment by a direct-current, cold atmospheric-pressure air plasma microjet. Plasma Process. Polym. 2010, 7, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolezalova, E.; Lukes, P. Membrane damage and active but nonculturable state in liquid cultures of Escherichia coli treated with an atmospheric pressure plasma jet. Bioelectrochem 2015, 103, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marnett, L.J. Lipid peroxidation—DNA damage by malondialdehyde. Mutat. Res. 1999, 424, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Bai, F.; Xiu, Z. Oxidative stress induced in Saccharomyces cerevisiae exposed to dielectric barrier discharge plasma in air at atmospheric pressure. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2010, 38, 1885–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiyuan, N.; Longfei, J.; Jinhai, N.; Hongyu, F.; Ying, S.; Qi, Z.; Dongping, L. Plasma inactivation of Escherichia coli cells by atmospheric pressure air brush-shape plasma. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2013, 234, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; He, B.; Chen, Q.; Li, J.; Xiong, Q.; Yue, G.; Zhang, X.; Yang, S.; Liu, H.; Liu, Q.H. Direct synthesis of hydrogen peroxide from plasma-water interactions. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 38454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyer, K.; Gort, A.S.; Imlay, J.A. Superoxide and the production of oxidative DNA damage. J. Bacteriol. 1995, 177, 6782–6790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.Y.; Häder, D.P. Reactive oxygen species and UV-B: Effect on cyanobacteria. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2002, 1, 729–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, M.J. Singlet oxygen-mediated damage to proteins and its consequences. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003, 305, 761–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, P.E.; Dean, R.T.; Davies, M.J. Protective mechanisms against peptide and protein peroxides generated by singlet oxygen. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2004, 36, 484–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cadet, J.; Douki, T.; Ravanat, J.L. Oxidatively generated damage to the guanine moiety of DNA: Mechanistic aspects and formation in cells. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008, 41, 1075–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.Y.; Muller, J.G.; Ye, Y.; Burrows, C.J. DNA-protein cross-links between guanine and lysine depend on the mechanism of oxidation for formation of C5 vs C8 guanosine adducts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 703–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.Y.; Park, S.; Choe, W.; Yong, H.Y.; Jo, C.; Kim, K. Plasma-functionalized solution: A potent antimicrobial agent for biomedical applications from antibacterial therapeutics to biomaterial surface engineering. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 2017, 9, 43470–43477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staehelin, J.; Hoigné, J. Decomposition of ozone in water in the presence of organic solutes acting as promoters and inhibitors of radical chain reactions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1985, 19, 1206–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, G.; Ricevuti, G.; Galoforo, A.; Franzini, M. Microbiological aspects of ozone: Bactericidal activity and antibiotic/antimicrobial resistance in bacterial strains treated with ozone. Ozone 2018, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, F.C. Antimicrobial reactive oxygen and nitrogen species: Concepts and controversies. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2004, 2, 820–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnabel, U.; Andrasch, M.; Weltmann, K.D.; Ehlbeck, J. Inactivation of vegetative microorganisms and Bacillus atrophaeus endospores by reactive nitrogen species (RNS). Plasma Process. Polym. 2014, 11, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, A.W.; Schoenfisch, M.H. Nitric oxide release: Part II. Therapeutic applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 3742–3752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voskuil, M.I. Inhibition of respiration by nitric oxide induces a Mycobacterium tuberculosis dormancy program. J. Exp. Med. 2003, 198, 705–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodmansee, A.N.; Imlay, J.A. A mechanism by which nitric oxide accelerates the rate of oxidative DNA damage in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 2003, 49, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schapiro, J.M.; Libby, S.J.; Fang, F.C. Inhibition of bacterial DNA replication by zinc mobilization during nitrosative stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 8496–8501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepoivre, M.; Fieschi, F.; Coves, J.; Thelander, L.; Fontecave, M. Inactivation of ribonucleotide reductase by nitric oxide. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1991, 179, 442–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oehmigen, K.; Hähnel, M.; Brandenburg, R.; Wilke, C.; Weltmann, K.D.; Von Woedtke, T. The role of acidification for antimicrobial activity of atmospheric pressure plasma in liquids. Plasma Process. Polym. 2010, 7, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gils, C.A.J.; Hofmann, S.; Boekema, B.K.H.L.; Brandenburg, R.; Bruggeman, P.J. Mechanisms of bacterial inactivation in the liquid phase induced by a remote RF cold atmospheric pressure plasma jet. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2013, 46, 175203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergei, V.; Lymar, I.; Hurst, J.K. CO2-catalyzed one-electron oxidations by peroxynitrite: properties of the reactive intermediate. Inorg. Chem. 1998, 37, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabiscol, E.; Tamarit, J.; Ros, J. Oxidative stress in bacteria and protein damage by reactive oxygen species. Int. Microbiol. 2000, 3, 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Imlay, J.A. The molecular mechanisms and physiological consequences of oxidative stress: Lessons from a model bacterium. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2013, 11, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castello, P.R.; David, P.S.; McClure, T.; Crook, Z.; Poyton, R.O. Mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase produces nitric oxide under hypoxic conditions: Implications for oxygen sensing and hypoxic signaling in eukaryotes. Cell Metab. 2006, 3, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Missall, T.A.; Lodge, J.K.; McEwen, J.E. Mechanisms of resistance to oxidative and nitrosative stress: Implications for fungal survival in mammalian hosts. Eukaryot. Cell 2004, 3, 835–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tillmann, A.; Gow, N.A.R.; Brown, A.J.P. Nitric oxide and nitrosative stress tolerance in yeast. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2011, 39, 219–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Collins, G.; Pruden, A. Differential gene expression in Escherichia coli following exposure to nonthermal atmospheric pressure plasma. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2009, 107, 1440–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barjasteh, A.; Dehghani, Z.; Lamichhane, P.; Kaushik, N.; Choi, E.H.; Kaushik, N.K. Recent progress in applications of non-thermal plasma for water purification, bio-sterilization, and decontamination. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai-Prochnow, A.; Clauson, M.; Hong, J.; Murphy, A.B. Gram positive and Gram negative bacteria differ in their sensitivity to cold plasma. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 38610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smet, C.; Govaert, M.; Kyrylenko, A.; Easdani, M.; Walsh, M.L.; Van Impe, J.F. Inactivation of single strains of Listeria monocytogenes and Salmonella Typhimurium planktonic cells biofilms with plasma activated liquids. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soušková, H.; Scholtz, V.; Julák, J.; Kommová, L.; Savická, D.; Pazlarová, J. The survival of micromycetes and yeasts under the low-temperature plasma generated in electrical discharge. Folia Microbiol. 2011, 56, 77–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Ruan, R.; Mok, C.K.; Huang, G.; Lin, X.; Chen, P. Inactivation of Escherichia coli on almonds using nonthermal plasma. J. Food Sci. 2007, 72, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, A.; Noriega, E.; Thompson, A. Inactivation of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium on fresh produce by cold atmospheric gas plasma technology. Food Microbiol. 2013, 33, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.P.; Su, T.L.; Liang, J. Plasma-activated solutions for bacteria and biofilm inactivation. Curr. Bioact. Compd. 2016, 13, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurita, R.; Barbieri, D.; Gherardi, M.; Colombo, V.; Lukes, P. Chemical analysis of reactive species and antimicrobial activity of water treated by nanosecond pulsed DBD air plasma. Clin. Plasma Med. 2015, 3, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harley, J.C.; Suchowerska, N.; McKenzie, D.R. Cancer treatment with gas plasma and with gas plasma–activated liquid: Positives, potentials and problems of clinical translation. Biophys. Rev. 2020, 12, 989–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milhan, N.V.M.; Chiappim, W.; Sampaio, A.G.; Vegian, M.R.C.; Pessoa, R.S.; Koga-Ito, C.Y. Applications of plasma-activated water in dentistry: A review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, Q.; Fan, L.; Li, Y.; Dong, S.; Li, K.; Bai, Y. A review on recent advances in plasma-activated water for food safety: Current applications and future trends. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 62, 2250–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herianto, S.; Hou, C.Y.; Lin, C.M.; Chen, H.L. Nonthermal plasma-activated water: A comprehensive review of this new tool for enhanced food safety and quality. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2021, 20, 583–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Li, Y.L.; Liu, C.M.; Tian, Y.; Yu, S.; Wang, K.L.; Zhang, J.; Fang, J. Investigation of cold atmospheric plasma-activated water for the dental unit waterline system contamination and safety evaluation in vitro. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 2017, 37, 1091–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q.; Dong, X.; Yu, H.; Sun, H.; Chen, M.; Wang, Y.; Yu, Q. The antimicrobial property of plasma activated liquids (PALs) against oral bacteria Streptococcus mutans. Dental 2021, 3, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdikia, H.; Shokri, B.; Majidzadeh, K. The feasibility study of plasma-activated water as a physical therapy to induce apoptosis in Melanoma Cancer cells in-vitro. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. 2021, 20, 337–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Xu, R.B.; Gou, L.; Liu, Z.C.; Zhao, Y.M.; Liu, D.X.; Zhang, L.; Chen, H.L.; Kong, M.G. Mechanism of virus inactivation by cold atmospheric-pressure plasma and plasma-activated water. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 84, e00726-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Tian, Y.; Zhou, H.Z.; Li, Y.L.; Zhang, Z.H.; Jiang, B.Y.; Yang, B.; Zhang, J.; Fang, J. Inactivation efficacy of non-thermal plasma activated solutions against Newcastle disease virus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 84, e02836-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, R.; Yu, S.; Tian, Y.; Wang, K.; Sun, C.; Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Chen, K.; Fang, J. Effect of non-thermal plasma-activated water on fruit decay and quality in postharvest Chinese bayberries. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 9, 1825–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Huang, K.; Wang, X.; Lyu, C.; Yang, N.; Li, Y.; Wang, J. Inactivation of yeast on grapes by plasma-activated water and its effects on quality attributes. Food Prot. 2017, 80, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, C.Y.; Lai, Y.C.; Hsiao, C.P.; Chen, S.Y.; Liu, C.T.; Wu, J.S.; Lin, C.M. Antibacterial activity and the physicochemical characteristics of plasma activated water on tomato surfaces. LWT 2021, 149, 111879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Liu, C.H.; Jiang, A.L.; Guan, Q.X.; Sun, X.Y.; Liu, S.S.; Hao, K.X.; Hu, W.Z. The effects of cold plasma-activated water treatment on the microbial growth and antioxidant properties of fresh-cut pears. Food Bioproc. Technol. 2019, 12, 1842–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Chen, R.C.; Liu, D.P.; Wang, W.C.; Niu, J.H.; Yang, X.; Qi, Z.H.; Zhao, Z.G.; Song, Y. Effect of nonthermal plasma-activated water on quality and antioxidant activity of freshcut kiwifruit. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2019, 47, 4811–4817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Chen, C.; Jiang, A.; Sun, X.; Guan, Q.; Hu, W. Effects of plasma-activated water on microbial growth and storage quality of fresh-cut apple. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 59, 102256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risa-Vaka, M.; Sone, I.; Garcia Alvarez, R.; Walsh, J.L.; Prabhu, L.; Sivertsvik, M.; Noriega Fernandez, E. Towards the next generation disinfectant: Composition, storability and preservation potential of plasma activated water on baby spinach leaves. Foods 2019, 8, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnabel, U.; Sydow, D.; Schlüter, O.; Andrasch, M.; Ehlbeck, J. Decontamination of fresh-cut iceberg lettuce and fresh mung bean sprouts by non-thermal atmospheric pressure plasma processed water (PPW). Mod. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2015, 1, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berardinelli, A.; Pasquali, F.; Cevoli, C.; Trevisani, M.; Ragni, L.; Mancusi, R.; Manfreda, G. Sanitisation of fresh-cut celery and radicchio by gas plasma treatments in water medium. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2016, 111, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Chen, R.; Tian, E.; Liu, D.; Niu, J.; Wang, W.; Qi, Z.; Xia, Y.; Song, Y.; Zhao, Z. Plasma-activated water treatment of fresh beef: Bacterial inactivation and effects on quality attributes. Trans. Plasma Sci. 2018, 4, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotfy, K.; Khalil, S. Effect of plasma-activated water on microbial quality and physicochemical properties of fresh beef. Open Phys. 2022, 20, 573–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.; Xiang, Q.; Zhao, D.; Wang, W.; Niu, L.; Bai, Y. Inactivation of Pseudomonas deceptionensis CM2 on chicken breasts using plasma-activated water. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 56, 4938–4945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Royintarat, T.; Choi, E.H.; Boonyawan, D.; Seesuriyachan, P.; Wattanutchariya, W. Chemical-free and synergistic interaction of ultrasound combined with plasma-activated water (PAW) to enhance microbial inactivation in chicken meat and skin. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Han, R.; Liao, X.; Ding, T. Application of plasma-activated water (PAW) for mitigating methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) on cooked chicken surface. LWT 2021, 137, 110465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.M.; Chu, Y.C.; Hsiao, C.P.; Wu, J.S.; Hsieh, C.W.; Hou, C.Y. The optimization of plasma-activated water treatments to inactivate Salmonella enteritidis (ATCC 13076) on shell eggs. Foods 2019, 8, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.M.; Hsiao, C.P.; Lin, H.S.; Liou, J.S.; Hsieh, C.W.; Wu, J.S.; Hou, C.Y. The Antibacterial Efficacy and Mechanism of Plasma-Activated Water Against Salmonella enteritidis (ATCC 13076) on Shell Eggs. Foods 2020, 9, 1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, X.Y.; Su, Y.; Liu, D.H.; Chen, S.G.; Hu, Y.Q.; Ye, X.Q.; Wang, J.; Ding, T. Application of atmospheric cold plasma-activated water (PAW) ice for preservation of shrimps (Metapenaeus ensis). Food Control 2018, 94, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Z.; Zhu, Y.P.; Xu, H.B.; Ma, R.N. Plasma-activated water ice inactivation of Listeria monocytogenes in pure culture and salmon strips. J. Zhejiang Univ. 2019, 51, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.M.; Ojha, S.; Burgess, C.M.; Sun, D.W.; Tiwari, B.K. Influence of various fish constituents on inactivation efficacy of plasma-activated water. Int. J. Food Sci. 2020, 55, 2630–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.M.; Oliveira, M.; Burgess, C.M.; Cropotova, J.; Rustad, T.; Sun, D.W.; Tiwari, B.K. Combined effects of ultrasound, plasma-activated water, and peracetic acid on decontamination of mackerel fillets. LWT 2021, 150, 111957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, M.; Meng, X.; Bai, Y.; Dong, X. Effect of plasma-activated water on Shewanella putrefaciens populations growth and quality of Yellow River carp (Cyprinus carpio) fillets application of PAW in the preservation of carp fillets. Food Prot. 2021, 84, 1722–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Physical Properties of PAW | ||||||

| Plasma Generating Equipment | Working Gas | Time of Activation (min) | pH | Conductivity (µS/cm) | Redox Potential (mV) | References |

| Plasma microjet | Air Ar/O2 | 20 20 | 2.3 6.1 | - 18.8 | 540 250 | [24] [25] |

| Plasma jet | Ar/O2 | 15 | 3.0 3.7 | 450 218 | 550 467 | [26] [27] |

| Low frequency plasma jet | He | 5 | 4.2 | - | - | [28] |

| Gliding arc | Air O2 N2 Ar | 15 | 2.8 3.2 3.0 3.6–3.7 | 1100 300 500 50–70 | - - - - | [29] [29] [29] [30] |

| DBD micro discharge | Air | 15 | 2.7 | - | - | [31] |

| DBD | Air O2 | 20 | 2.1 2.2 | - - | - - | [32] [32] |

| DBD with hallow electrodes | Air | 10 | 1.9 | 2000 | 550 | [33] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Małajowicz, J.; Khachatryan, K.; Kozłowska, M. Properties of Water Activated with Low-Temperature Plasma in the Context of Microbial Activity. Beverages 2022, 8, 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages8040063

Małajowicz J, Khachatryan K, Kozłowska M. Properties of Water Activated with Low-Temperature Plasma in the Context of Microbial Activity. Beverages. 2022; 8(4):63. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages8040063

Chicago/Turabian StyleMałajowicz, Jolanta, Karen Khachatryan, and Mariola Kozłowska. 2022. "Properties of Water Activated with Low-Temperature Plasma in the Context of Microbial Activity" Beverages 8, no. 4: 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages8040063

APA StyleMałajowicz, J., Khachatryan, K., & Kozłowska, M. (2022). Properties of Water Activated with Low-Temperature Plasma in the Context of Microbial Activity. Beverages, 8(4), 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages8040063