An Assessment of the Competitive Position of the Emergent Uruguayan Wine Industry: A Preliminary Netnographic Baseline Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Scope of the Research

3. Literature Review

Historical Highlights and Current Developments

4. Theoretical Background

4.1. Theoretical Framework

4.2. Strategic Choice

4.2.1. Cost Leadership

4.2.2. Differentiation

4.2.3. Focus

5. Research questions

- A.

- What are the critical competing factors of the Uruguayan wine industry?

- B.

- How do these factors compare to global competitors?

- C.

- What are the opportunities for the Uruguayan wine industry to become a competitive player in the global wine business landscape?

6. Methodology

6.1. Research Design

6.2. Data Collection

7. Findings

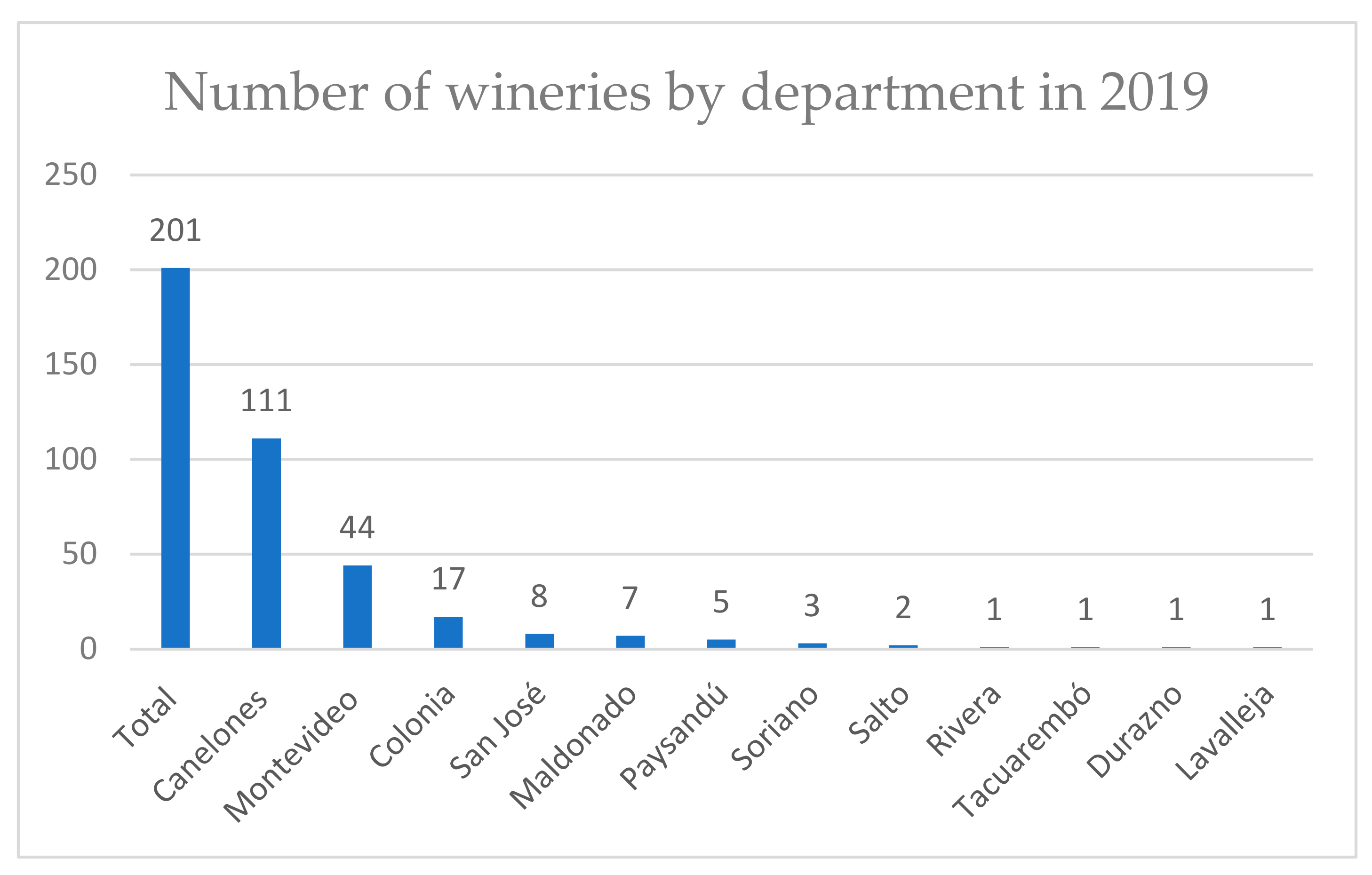

7.1. Factors of Production

7.2. Aggregate Production by Grape Type

8. Synthesis and Discussion

8.1. Critical Success/Failure Factors of the Uruguayan Wine Industry

8.1.1. The Factor “Land”

8.1.2. The Factor “Human” (Labor)

8.1.3. The Factor “Capital”

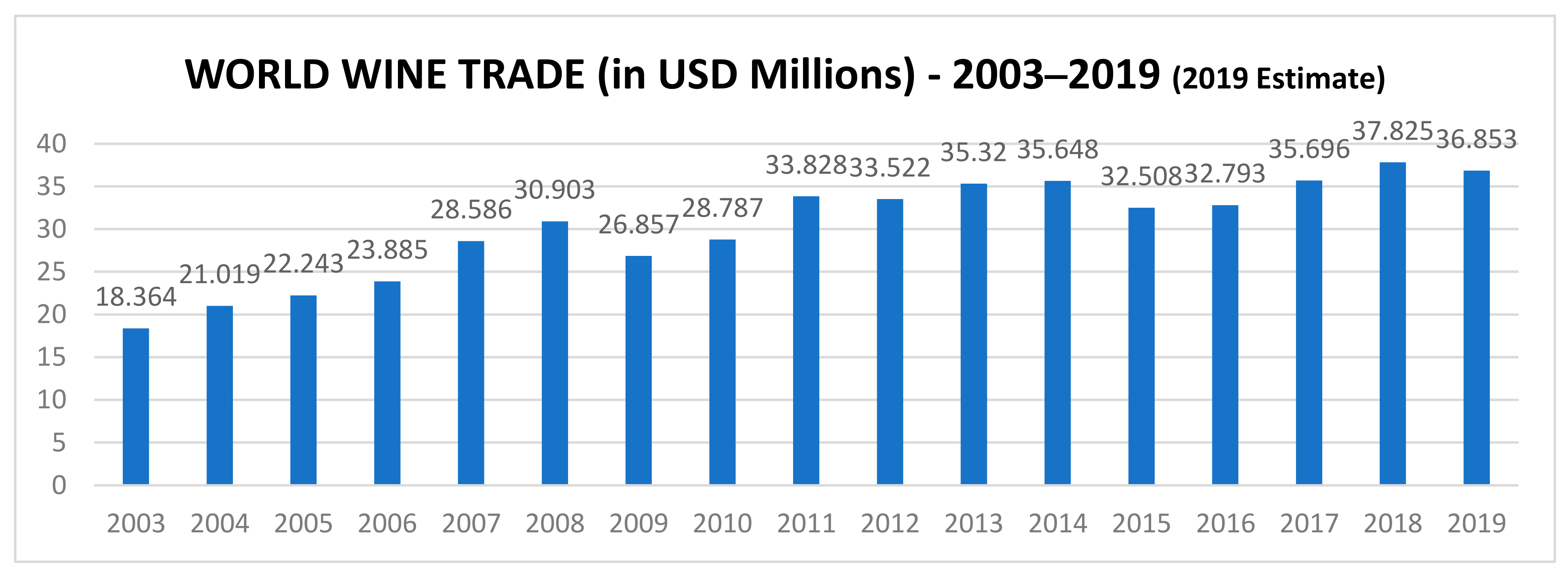

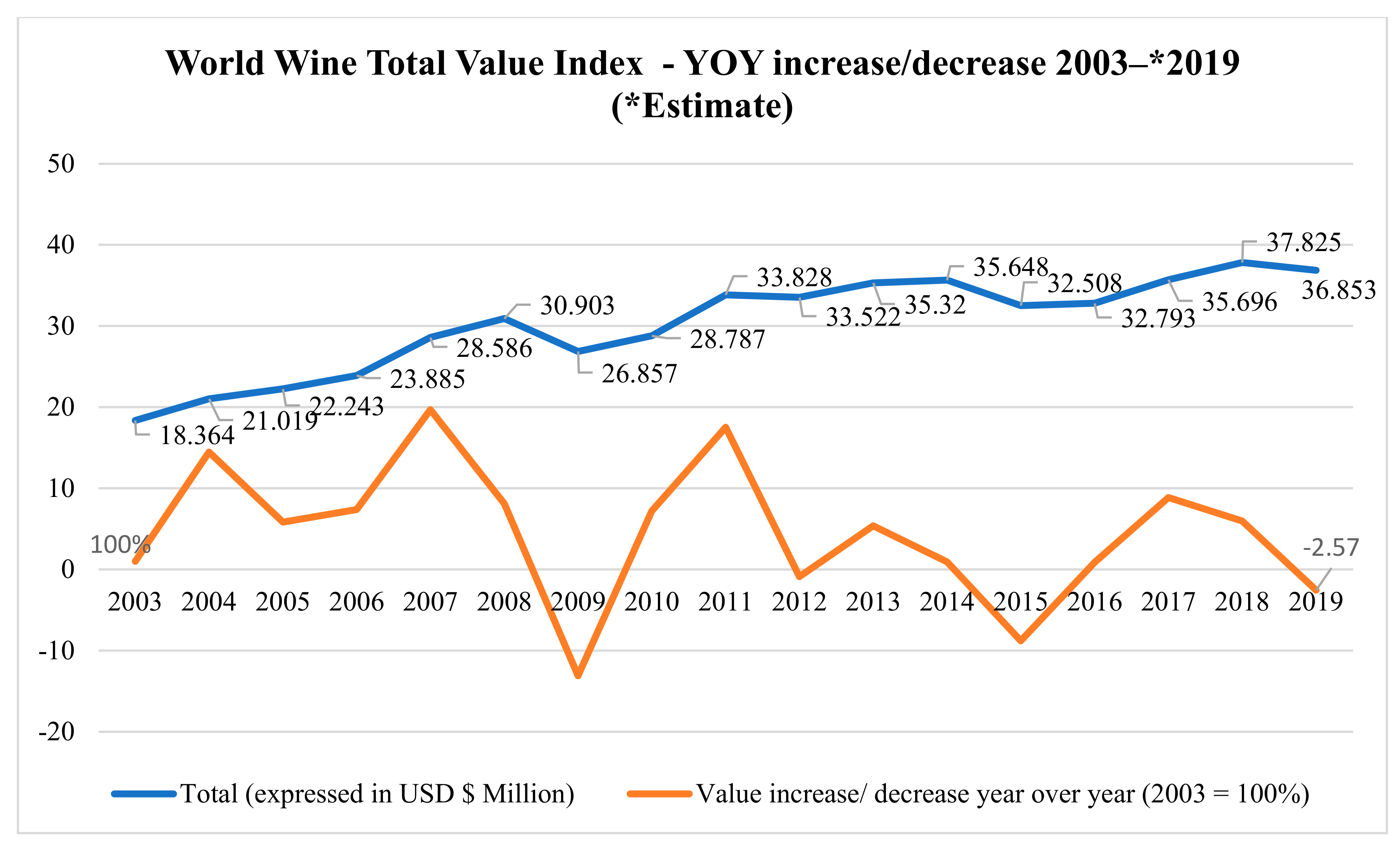

8.1.4. The “Supply and Demand” Factors

8.2. Answer to the Research Questions

- A.

- What are the critical competing factors of the Uruguayan wine industry?

- Being one of the countries in the southern hemisphere to produce wine earlier provides a first mover’s advantage in experimentation, new product release, immediate corrective action if needed, earlier market penetration, and monitoring of competitors in the rest of the world.

- The geographic location, favorable climate, terrain, hydropower and the high density of the hydrographic network, available agricultural land, an available and well-educated workforce, unique land infrastructure, the newness of grape varietal (Tannat) being introduced to the world market with positive results, the government support to aid the industry and grow the export business, as well as complementary economic developments such as enotourism and its multiplier effect and its contribution to the local economy. Since the data were collected using cyberethnography without interviewing key players and a sample of the population, the list presented above may not be exhaustive.

- The attractiveness of the industry and the political landscape may attract investors interested in investing in the wine industry, both domestic and foreign. Although Uruguay’s ranking in terms of ease to do business is not high, it moves upward. This is supported by the membership with the Mercosur, OIV, and the preferred trade relations with the EU and the United States. Uruguay has benefited from export surplus, indicating that the wine industry could follow suit and positively contribute to the country’s GDP.

- B.

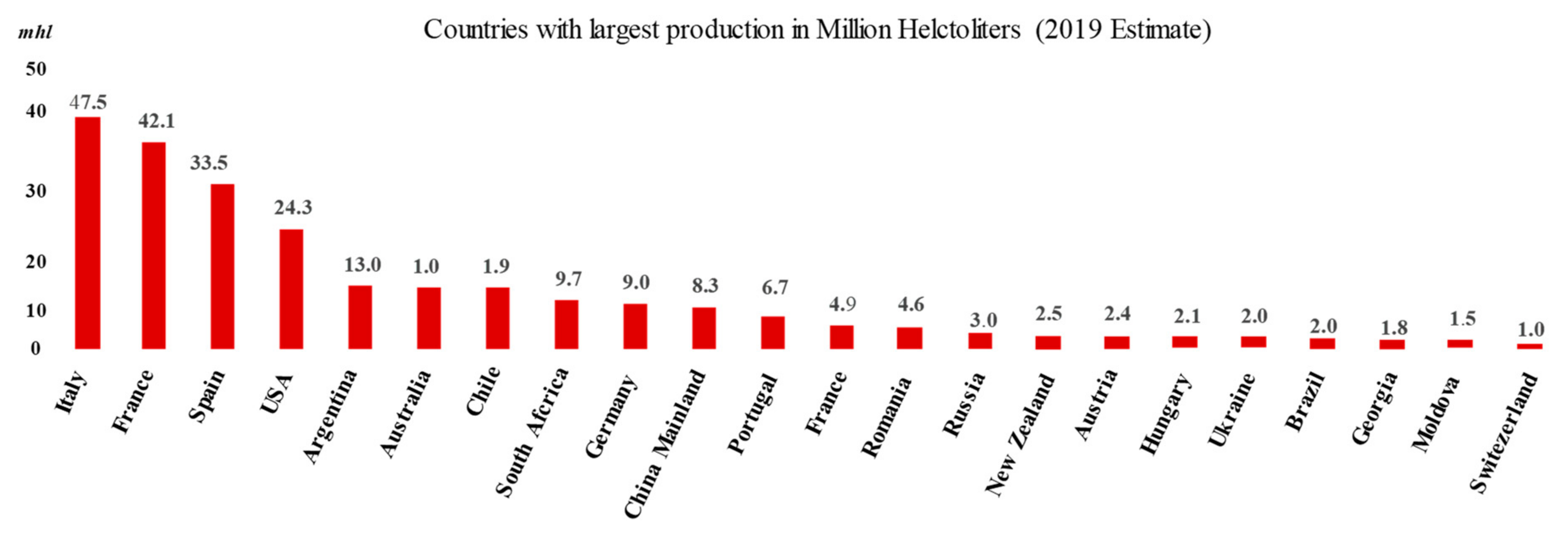

- How do these factors compare to global competitors?

- Being a young wine-producing country, the grape and wine production infrastructure is also new, which means that Uruguay has a significant advantage in using the latest technology, the latest and most efficient viticultural and enological management practices, and can become completely environmentally sustainable before other established countries. In 2019, Uruguay became the first country in the world to implement traceability technology and track all agricultural products. Currently, about 73% of the workforce is employed in the service industry, which means that it is well-trained technologically. Being over 90% dependable on renewal energy is also an asset. This technological advancement can significantly benefit the wine industry, especially the viticultural sector. Uruguay has less dependency on imported fuel and natural gas while striving to become competitively sustainable.

- C.

- What are the opportunities for the Uruguayan wine industry to become a competitive player in the global wine business landscape?

- In 1987, the Uruguayan Government enacted a law to create the National Institute of Vitiviniculture (INAVI) [6], which was assigned with the legal status of a person of non-state public law and with legal headquarters in the city of Las Piedras, department of Canelones. In January 1988, INAVI formally began operating as the governing body of the country’s wine policy. Today, INAVI is the governing body of all wine activity in the country. It has the legal authority to control the production process, regulate volume and quality, and develop the industrial process. INAVI plays a vital role in the promotion, development, and research of wine activities. In addition to the tasks assigned by law, INAVI has the function of advising the Executive Power on a mandatory basis and supervising compliance with the regulations that are issued in the wine sector. In collaboration with other governmental agencies, the agency is a catalyst for significant activities in establishing a booming and globally competitive wine industry.As an example, a particular project supported by INAVI was launched in 2019 to end in 2022, with the title “Adjustment, dissemination, and application of the integrated production regulations for wine grapes, aligned with the demands of the international wine market” [1]. The scope is to strive to consolidate a sustainable and differentiated production system in Uruguayan viticulture under an integrated production standard. The goal is to make the Uruguayan wine industry achieve better conditions of competitiveness to meet an increasingly demanding international wine market in terms of environmental care, food safety, and worker safety in production systems. Therefore, it would be possible to increase the volume of wine placement in the international market, while meeting the required quality standards, and ensuring a product with a low content of pesticide residues and the lowest impact on the general environment [23].

- By achieving the same or exceeding the standard of competing countries, Uruguay can position itself as a global player in the global marketplace. Uruguayan wine producers are striving to become global players, and as such, the government holds a membership with the OIV, The International Organization of Vine and Wine, an intergovernmental organization made up of members from 47 wine-producing countries [7]. Membership allows access to data, competition, education, and other benefits and compels members to act according to the organization’s rules. OIV and INAVI are the primary sources of the data gathered for the study, although additional, non-scientific data were gathered from other sources.

8.3. Proposed Strategies for Growth and Exploitation Factors

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baptista, B. La temprana vitivinicultura en Uruguay: Surgimiento y consolidación (1870–1930). Am. Lat. Hist. Econ. 2008, 29, 99–129. Available online: http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1405-22532008000100003&lng=es&tlng=es (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- Carrau, F.M. The emergence of a new Uruguayan wine industry. J. Wine Res. 1997, 8, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanti, A. El Vino. La Industria Vitivinícola Uruguaya. Estudio Crítico Ilustrado; Tipograpfia Italia: Mendoza, Argentina, 1919; pp. 73–173. Available online: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.$c47020&view=1up&seq=7 (accessed on 13 June 2020).

- Frutos, E.D.; Curi, A.B. Desafíos y proyección de una viticultura joven de escala reducida: Tannat del Uruguay. BIO Web Conf. 2019, 12, 03007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bodega Garzon. Premios Y Reconocimientos, Nuestros Vinos Premiados a Nivel Internacional. Bodega Garson, Uruguay. Available online: https://bodegagarzon.com/es/premios/?concurso=wine-spectator&wine_sel=&pais=&galardon=&year_sel= (accessed on 20 May 2020).

- INAVI. Estadísticas Anuales De Viñedos—2019 Datos Departamentales. Instituto Nacional de Vitivinicultura (INAVI). 2020. Available online: http://www.inavi.com.uy/vinedos/estadisticas (accessed on 22 June 2020).

- OIV. 2019 Wine Production; International Organisation of Vine and Wine Intergovernmental Organisation: Paris, France, 2020; Available online: http://www.oiv.int/en/statistiques (accessed on 20 May 2020).

- Analist Group. Precision Farming with the Drone: NDVI Vineyard Analysis. How to generate and analyze the NDVI of a Vineyard with the Drone for Precision Farming. Available online: https://blog.analistgroup.com/en/precision-farming-with-the-drone-ndvi-vineyard-analysis/ (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- Smith, P. Drones in Precision Agriculture. DroneBelow.com. 2019. Available online: https://dronebelow.com/2018/07/19/drones-in-precision-agriculture (accessed on 25 June 2020).

- Carpenter, G.; Humphreys, A. Disruptive Innovation. What the Wine Industry Understands about Connecting with Consumers. Harvard Business Review Online Edition 2019. Available online: https://hbr.org/2019/03/what-the-u-s-wine-industry-understands-about-connecting-with-customers (accessed on 25 June 2020).

- Cooper, J.O.; Heron, T.E.; Heward, W.L. Applied Behavioral Analysis, 2nd ed.; Pearson Education, Inc.: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- GIZ. Baseline Study of the Armenian Wine Sector. Development Strategy for 2015–2025; GIZ (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit, GmbH): Bonn, Germany; iCare (The International Center for Agribusiness Research and Education): Yerevan, Armenia, 2014; Available online: https://icare.am/arc/publications (accessed on 7 August 2019).

- Barreto, S. La escuela agricola ‘Jackson’ de El Manga. Rev. Union Viticultores Bodeg. 1936, 135, 4–19. [Google Scholar]

- Barreto, S. Cartillas Comision Pro-lndustria Vitivinicola; Ministerio de Lndustria: Montevideo, Uruguay, 1932. [Google Scholar]

- Varzi, P. La lndustria Vitivinicolaen Nuestro Pais; El Economista Umguayo: Montevideo, Uruguay, 1917. [Google Scholar]

- Versini, G.; Carrau, F.M.; Gioia, O.; Dalla Serra, A. Caracterizacion de perfil aromatico del vino Moscatel Miel de Uruguay y su relacion con otros Moscateles. In Proceedings of the XXI Congreso Mundial de la Viña y el Vino de OIV, Punta del Este, Uruguay, 27–30 November 1995; pp. 173–174. [Google Scholar]

- CNN. Why Uruguay Could Be the World’s Next Great Wine Destination. 11 March 2020. Available online: https://www.cnn.com/travel/article/uruguay-winery-bodega-garzn/index.html (accessed on 15 May 2020).

- Cicchetti, D.V. Who won the 1976 blind tasting of French Bordeaux and US Cabernets? Parametrics to the rescue. J. Wine Res. 2004, 15, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulkower, N.D. The judgment of Paris according to Borda. J. Wine Res. 2009, 20, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taber, G.M. Judgment of Paris: California vs. France and the Historic 1976 Paris Tasting that Revolutionized Wine; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA. Available online: https://www.simonandschuster.com/books/Judgment-of-Paris/George-M-Taber/9780743297325 (accessed on 20 May 2020).

- Kim, C.W.; Mauborgne, R. Blue Ocean Strategy: How to Create Uncontested Market Space and Make the Competition Irrelevant; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2005; Volume 28, pp. 31–32. [Google Scholar]

- INAVI. VINOS URUGUAYOS PREMIADOS EN EL MUNDO. Uruguay Obtuvo Ocho Medallas -Dos De Oro Y Seis De Plata- En Las Ediciones 2020 De Los Concursos Vinalies Internationales Y Concurso Internacional De Vinos Bacchus. 2020. Available online: http://www.inavi.com.uy/noticias/vinos-uruguayos-premiados-en-el-mundo (accessed on 20 May 2020).

- INIA. Special Research Project. National Institute for Agricultural Research. 2020. Available online: http://www.inia.uy/Proyectos/Paginas/FPTA_353.aspx# (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- Uruguay XXI. Vinos Uruguayos De Calidad Histórica Se Preparan Para Salir Al Mundo. Uruguay XXI, Promoción De Exportaciones, Inversiones e Imagen País. 2020. Available online: https://www.uruguayxxi.gub.uy/es/noticias/articulo/vinos-uruguayos-de-calidad-historica-se-preparan-para-salir-al-mundo (accessed on 20 May 2020).

- Camillo, A.A.; Holt, S.; Marques, J.; Hu, J. A strategic analysis of the competing factors in the global wine trade and the development of a mode. In Handbook of Research on Effective Marketing in Contemporary Globalism; Christiansen, B., Yıldız, S., Yıldız, E., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2014; pp. 281–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. How competitive forces shape strategy. Harvard Business Review, March–April 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E. Competitive Strategy: Technique for Analyzing Industries and Competitors; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E. The Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E. (Ed.) Competition in global industries: A conceptual framework. In Competition in Global Industries; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Hitt, M.A.; Ireland, R.D. Corporate distinctive competence, strategy, industry and performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 1985, 6, 273–293, July–September. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljungquist, U. Core competency beyond identification: Presentation of a model. Manag. Decis. 2007, 45, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooney, A. Core competence, distinctive competence, and competitive advantage: What is the difference? J. Educ. Bus. 2007, 83, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C.; Hamel, G. The core competence of the corporation. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1990, 68, 79–91. [Google Scholar]

- Snow, C.C.; Hrebiniak, L.G. Strategy, distinctive competence, and organizational performance. In Strategic Management Concepts and Cases, 3rd ed.; Thompson, A.A., Jr., Strickland, A.J., Eds.; Business Publications: Piano, TX, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Stoner, C.R. Distinctive competence and competitive advantage. J. Small Bus. Manag. 1987, 25, 33–46. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C. The integrated model of core competence and core capability. Total Qual. Manag. 2015, 26, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G. The dynamic capabilities of firms: An introduction. Ind. Corp. Chang. 1994, 3, 537–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMIllan, B. The State of the U.S. Wine Industry 2021; Silicon Valley Bank, Wine Division: Santa Clara, CA, USA, 2021; p. 4. Available online: https://www.svb.com/globalassets/trendsandinsights/reports/wine/sotwi-2021/svb-state-of-the-wine-industry-report-2021.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2021).

- Barney, J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apstein, M. Wine Pricing, Still Economics 101. Wine Review Online.com. Available online: http://www.winereviewonline.com/Michael_Apstein_on_wine_pricing.cfm (accessed on 22 September 2019).

- Camillo, A.A. An analysis of wine list engineering of Three Michelin Star U.S. restaurants: A preliminary study. 2020, Unpublished manuscript.

- Précis of the, U.S. Wine Market and Three-tier Sales Channel. Tincknell & Tincknell, wine sales and marketing consultants. Available online: https://marketingwine.nfshost.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/tt-precis-of-us-wine-market-and-three-tier-sales-channel.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2020).

- Kozinets, R.V. I want to believe’: A netnography of the X-Philes’ subculture of consumption. Adv. Consum. Res. 1997, 24, 470–475. Available online: http://acrwebsite.org/volumes/8088/volumes/v24/NA-24 (accessed on 22 June 2020).

- Kozinets, R.V. The field behind the screen: Using netnography for marketing research in online communities. J Mark. Res. 2002, 39, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozinets, R.V.; Dolbec, P.Y.; Earley, A. Netnographic analysis: Understanding culture through social media data. In Sage Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis; Flick, U., Ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2014; pp. 262–275. [Google Scholar]

- Fait, M.; Cavallo, F.; Maizza, A.; Iaia, L.; Scorrano, P. An interpretative model for the Web image analysis: The case of a wine tourism destination. In Proceedings of the International Conference of the Society for Global Business & Economic Development, Ancona, Italy, 16–18 July 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Puri, A. The web of insights: The art and practice of webnography. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2007, 49, 387–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, J.; Xun, J. Applying netnography to market research: The case of the online forum. J Target. Meas. Anal. Mark. 2010, 18, 17–31. [Google Scholar]

- Monder, R. Trading places: The ethnographic process in small firms’ research. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 1999, 11, 95–108. [Google Scholar]

- Willis, D.G.; Sullivan-Bolyai, S.; Knafl, K.; Cohen, M.Z. Distinguishing features and similarities between descriptive phenomenological and qualitative description research. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2016, 38, 1185–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Åkerlind, G.S. Variation and commonality in phenomenographic research methods. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2012, 31, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, B.L. Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences, 7th ed.; Pearson Education: Boston, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. World Population Prospects 2019, Online Edition. Rev. 1; United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division: New York, NY, USA, 2019; Available online: https://population.un.org/wpp/Download/Standard/Population (accessed on 22 June 2020).

- Zimmer, G. Harvest Report, Uruguay 2020; Gabi Zimmer Reports Web Publishing, Uruguay. Available online: https://gabizimmer.com/free-report (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- CIA. CIA World Fact Book, Uruguay. CIA Library. Available online: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/uy.html (accessed on 22 June 2020).

- Bodegas. Enoturismo. La Bodegas Del Uruguay. Available online: http://www.bodegasdeluruguay.com.uy/bodegas (accessed on 23 June 2020).

- Defiendace. Comodato vs Depósito. Sito de la Republica Argentina. Available online: https://www.defiendase.com/articulos/comodato-vs-deposito/2737 (accessed on 22 June 2020).

- Legal Dictionary. Meaning of Commodatum. Legal Dictionary. 2020. Available online: https://legal-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/commodatum (accessed on 22 June 2020).

- Global Edge. Global Insight: Uruguay, Introduction. Global Business Knowledge. 2020. Available online: https://globaledge.msu.edu/countries/uruguay (accessed on 19 June 2020).

- Global Edge. Global Insight: Uruguay, Trade Statistics. Global Business Knowledge. 2020. Available online: https://globaledge.msu.edu/countries/uruguay/tradestats (accessed on 19 June 2020).

- COFACE. Uruguay’s Micro Economic Indicators. Coface Economic Studies. Available online: https://www.coface.com/Economic-Studies-and-Country-Risks/Uruguay (accessed on 13 June 2020).

- Porter, M.E. The Five Competitive Forces That Shape Strategy. Harvard Business Review, January 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wine by Numbers. Global Trade 2019. A Statistical Analysis Provided by the Unione Italiana Vini. Association for The General Conservation of the Activities of the Wine Industry Economic Cycle. Il Corriere Vinicolo. Available online: www.winebynumbers.it (accessed on 20 May 2020).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| South America Wine Production 2020 Mhl (million Hectoliters) ** Estimate | South America Vineyard Surface Area in 2020-kha (1000 hectares) ** Estimate, ## Includes Non-Vinifera Grapes | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Argentine ** | 11,600,000 | Argentine | 215,000 |

| Chile ** | 10,500,000 | Chile | 220,000 |

| Brazil ** | 2,000,000 | Brazil | 81,000 |

| Uruguay ** | 650,000 | Peru ** ## | 11,000 |

| Peru ** | 610,000 | Uruguay | 5880 |

| Bolivia ** | 82,000 | Bolivia ** | 3000 |

| Total ** | 25,442,000 | Total ** | 535,880 |

| Type of Ownership | Number of Vineyards | Percentage Share Of the Land |

|---|---|---|

| Aparcero (sharecropper) | 56 | 4.4% |

| Arrendatario (tenant) | 259 | 20.3% |

| Comodatario(leaseholder) | 323 | 25.4% |

| Medianero (mediator) | 21 | 1.6% |

| Ocupante(tenant) | 11 | 0.9% |

| Poseedor (keeper, proprietor, possessor) | 2 | 0.2% |

| Propietario (proprietor, owner) | 578 | 45.4% |

| Usufructuario (usufructuary, tenant for life) | 6 | 0.5% |

| Otros (other types of ownership) | 18 | 1.4% |

| Total | 100% |

| Grape Type | Production in (kg) | Percentage | Surface (ha) | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Red grapes | 65,775,913 | 76% | 4942 | 80% |

| White grapes | 20,453,328 | 24% | 1202 | 20% |

| Total production % | 86,229,241 | 100% | 6144 | 100% |

| 2019 Statistics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Varietals | Surface | Production | ||

| Red Vinifera Grapes | ha (hectares) | Percent of National Surface | kg | Percent of National Production |

| Cot Rouge | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% |

| Bonarda | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% |

| Fortana | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% |

| Grand Noir (Granoir) | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% |

| Cereza O Criolla | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% |

| Jurançon Noir | 0.06 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% |

| Carignan | 0.11 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% |

| Gamay | 0.18 | 0.00% | 637 | 0.00% |

| Aubun | 0.27 | 0.00% | 1000 | 0.00% |

| Barbera | 0.99 | 0.02% | 9000 | 0.01% |

| Mourvedre | 1.11 | 0.02% | 3800 | 0.00% |

| Garnacha (Grenache) | 1.19 | 0.02% | 8700 | 0.01% |

| Cinsaut (Picapol) | 1.45 | 0.02% | 0 | 0.00% |

| Folle Noire (Vidiella) | 2.10 | 0.03% | 17,390 | 0.02% |

| Ruby Cabernet | 2.57 | 0.04% | 18,000 | 0.02% |

| Egiodola | 2.85 | 0.05% | 60,780 | 0.07% |

| Nebbiolo | 4.28 | 0.07% | 24,080 | 0.03% |

| Hibridos Tintos | 4.40 | 0.07% | 10,163 | 0.01% |

| Mezcla (Tinta) | 8.10 | 0.13% | 80,765 | 0.09% |

| Tempranillo | 15.83 | 0.26% | 191,174 | 0.22% |

| Alicante Bouchet | 20.60 | 0.34% | 472,110 | 0.55% |

| Concord | 24.26 | 0.39% | 472,965 | 0.55% |

| Petit Verdot | 31.36 | 0.51% | 283,024 | 0.33% |

| Cot (Malbec) | 35.55 | 0.58% | 511,012 | 0.59% |

| Arinarnoa | 54.45 | 0.89% | 914,375 | 1.06% |

| Syrah | 55.97 | 0.91% | 606,520 | 0.70% |

| Pinot Noire | 58.44 | 0.95% | 316,437 | 0.37% |

| Frutilla | 66.02 | 1.07% | 606,450 | 0.70% |

| Otras Tintas De Vino | 70.03 | 1.14% | 580,698 | 0.67% |

| Marselan | 158.57 | 2.58% | 2,277,344 | 2.64% |

| Cabernet Franc | 239.40 | 3.90% | 2,500,526 | 2.90% |

| Cabernet Sauvignon | 397.93 | 6.48% | 3,433,035 | 3.98% |

| Merlot | 689.32 | 11.22% | 7,684,209 | 8.91% |

| Moscatel Hamburgo (Vino) | 1163.24 | 18.93% | 18,790,185 | 21.79% |

| Tannat (Harriague) | 1631.71 | 26.56% | 23,810,851 | 27.61% |

| Total Tintas Vino (Total Red Vinifera) | 4742 | 77.18% | 63,685,230 | 73.86% |

| 2019 Statistics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Varietals | Surface | Production | ||

| White Vinifera Grapes | ha (hectares) | Percent of Total National Surface | kg | Percent of Total National Production |

| Mezcla (Blanca) | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% |

| Chasselas | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% |

| Pedro Ximenez | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% |

| Colombard | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% |

| Ducomander | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% |

| Silvaner | 0.02 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% |

| Riesling Renano | 0.02 | 0.00% | 663 | 0.00% |

| Riesling Italico | 0.10 | 0.00% | 406 | 0.00% |

| Jacquere | 0.11 | 0.00% | 1010 | 0.00% |

| Falso Pinot | 0.14 | 0.00% | 1535 | 0.00% |

| Gross Manseng | 0.65 | 0.01% | 6689 | 0.01% |

| Folle Blanche | 1.26 | 0.02% | 0 | 0.00% |

| Muscat Ottonel | 1.27 | 0.02% | 7250 | 0.01% |

| Chenin | 1.74 | 0.03% | 57,670 | 0.07% |

| Marsanne | 2.00 | 0.03% | 14,988 | 0.02% |

| Roussanne | 3.01 | 0.05% | 19,883 | 0.02% |

| Pinot Blanco | 3.18 | 0.05% | 16,120 | 0.02% |

| Hibridos Blancos | 4.17 | 0.07% | 6810 | 0.01% |

| Riesling | 5.02 | 0.08% | 27,570 | 0.03% |

| Torrontes | 6.37 | 0.10% | 134,386 | 0.16% |

| Muscat De Frontignan | 6.84 | 0.11% | 94,380 | 0.11% |

| Arriloba | 7.09 | 0.12% | 132,282 | 0.15% |

| Trebbiano | 10.19 | 0.17% | 118,580 | 0.14% |

| Sauvignon Gris | 10.82 | 0.18% | 164,123 | 0.19% |

| Pinot Gris | 11.05 | 0.18% | 50,397 | 0.06% |

| Gewurztraminer | 12.84 | 0.21% | 58,816 | 0.07% |

| Semillon | 13.22 | 0.22% | 106,909 | 0.12% |

| Moscatel Blanco | 18.03 | 0.29% | 347,174 | 0.40% |

| Otras Blancas De Vino | 32.78 | 0.53% | 311,985 | 0.36% |

| Viogner | 47.52 | 0.77% | 492,215 | 0.57% |

| Albariño | 57.36 | 0.93% | 381,378 | 0.44% |

| Chardonnay | 104.49 | 1.70% | 1,208,042 | 1.40% |

| Sauvignon | 129.86 | 2.11% | 1,738,928 | 2.02% |

| Ugni Blanc | 646.45 | 10.52% | 14,099,416 | 16.35% |

| Total Blancas De Vino (Total white vinifera) | 1138 | 18.51% | 19,599,605 | 22.73% |

| Grapes Distributed to Buyers for Various Use or Processed for Own Production by Producers | ||

|---|---|---|

| Description | Production (kg) | Percentage |

| Sold To Wineries | 65.742.601 | 76.24% |

| Sold For Fresh Consumption | 2.630.405 | 3.05% |

| Sold To Individuals For Vinification | 89.872 | 0.10% |

| Vinified In Own Cellar | 16.701.410 | 19.37% |

| Sold To Cooperative Vineriw | 995.689 | 1.15% |

| Vinified For Own Consumption | 43.657 | 0.05% |

| Sold As Grape Juice | 25.607 | 0.03% |

| Total national production | 86.229.241 | 100% |

| Strengths | Weaknesses | Opportunities | Threats |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| Levels | Local | National | Global | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environment | ||||

| Political | Policies of local political entities: services available; eligibility. | National government policies: subsidies; grants; R&D funding. | Global trade agreements, double taxation, free trade zone, diplomatic relationship. | |

| Economic | Local income-per-capita; state of the local economy; economic resources. | Country’s fiscal policy; interest rates; government loans. | Cross-border opportunities and economic growth, trade balance, foreign reserves | |

| Social | Size and growth of local population, literacy, life expectancy. | Demographic changes: aging, family composition, migration, ethnicity, level of diversity and minorities | Migration and immigration; study abroad, cross-cultural family union | |

| Technological | Development and installation of new technologies | Country’s level of technological advancement and service provision | Global–technological changes; communication channels. | |

| Legal | Local law enforcement, licensing, permits, ease of doing business. | The Country’s “law of the land.” In commonwealth countries, it is the British law plus national amendments | International agreements on sustainability, human rights, freedom of speech, religion, and expression | |

| Environmental | Contribution to local environmental sustainability | National sustainability issues: air, water, and land pollution, preservation, and prevention initiatives | Global sustainability issues: air, water, and land pollution, preservation, and prevention initiatives–carbon footprints | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Camillo, A.A.; Kim, W.G. An Assessment of the Competitive Position of the Emergent Uruguayan Wine Industry: A Preliminary Netnographic Baseline Study. Beverages 2021, 7, 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages7020026

Camillo AA, Kim WG. An Assessment of the Competitive Position of the Emergent Uruguayan Wine Industry: A Preliminary Netnographic Baseline Study. Beverages. 2021; 7(2):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages7020026

Chicago/Turabian StyleCamillo, Angelo A., and Woo Gon Kim. 2021. "An Assessment of the Competitive Position of the Emergent Uruguayan Wine Industry: A Preliminary Netnographic Baseline Study" Beverages 7, no. 2: 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages7020026

APA StyleCamillo, A. A., & Kim, W. G. (2021). An Assessment of the Competitive Position of the Emergent Uruguayan Wine Industry: A Preliminary Netnographic Baseline Study. Beverages, 7(2), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages7020026