USA Mid-Atlantic Consumer Preferences for Front Label Attributes for Local Wine

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Wine Labels

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Choice-Based Conjoint Analysis (CBCA) and Psychographic Questionnaires

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Consumer Demographics

3.2. General Population Results from the CBCA Experiment

3.3. Differences in Consumer Psychographics and Wine Knowledge Affect Wine Label Preference

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Giacalone, D.; Jaeger, S.R. Better the Devil You Know? How Product Familiarity Affects Usage Versatility of Foods and Beverages. J. Econ. Psychol. 2016, 55, 120–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennsylvania Winery Association PA Grape Guide. Available online: https://pennsylvaniawine.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/PWA_WineGuide2020-GrapeGuide-2.pdf (accessed on 4 December 2020).

- DOT-TTB Department of the Treasury Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau Statistical Report-Wine. 2018. Available online: https://www.ttb.gov/statistics/wine-2018-statistics (accessed on 4 December 2020).

- Pennsylvania Winery Association; MKF Research LLC. The Economic Impact of Pennsylvania Wine, Wine Grapes and Juice Grapes-2011. Available online: https://pennsylvaniawine.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/PAWines_2007EconomicImpactReport.pdf (accessed on 4 December 2020).

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAA) Surveillance Report #110 Apparent per Capita Alcohol Conumsption: National, State, and Regional Tredns, 1977–2016. Available online: https://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/surveillance110/CONS16.htm (accessed on 19 January 2021).

- Kelley, K.M.; Hyde, J.; Bruwer, J.U.S. Wine Consumer Preferences for Bottle Characteristics, Back Label Extrinsic Cues and Wine Composition: A Conjoint Analysis. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2015, 27, 516–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennsylvania General Assembly 2016 Act 39 Liquor Code-Omnibus Amendments. Available online: https://www.lcb.pa.gov/Legal/Pages/Act39of2016.aspx (accessed on 4 August 2020).

- Mueller, S.; Szolnoki, G. The Relative Influence of Packaging, Labelling, Branding and Sensory Attributes on Liking and Purchase Intent: Consumers Differ in Their Responsiveness. Food Qual. Prefer. 2010, 21, 774–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celhay, F.; Remaud, H. What Does Your Wine Label Mean to Consumers? A Semiotic Investigation of Bordeaux Wine Visual Codes. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 65, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tonder, E.M.; Mulder, D. Marketing Communication for Organic Wine: Semiotic Guidelines for Wine Bottle Front Labels. Communicatio 2015, 41, 131–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrea, C.; Melo, L.; Evans, G.; Forde, C.; Delahunty, C.; Cox, D.N. An Investigation Using Three Approaches to Understand the Influence of Extrinsic Product Cues on Consumer Behavior: An Example of Australian Wines. J. Sens. Stud. 2011, 26, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garaus, M.; Halkias, G. One Color Fits All: Product Category Color Norms and (a)Typical Package Colors. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2020, 14, 1077–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lick, E.; König, B.; Kpossa, M.R.; Buller, V. Sensory Expectations Generated by Colours of Red Wine Labels. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 37, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gmuer, A.; Siegrist, M.; Dohle, S. Does Wine Label Processing Fluency Influence Wine Hedonics? Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 44, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáenz-Navajas, M.P.; Campo, E.; Sutan, A.; Ballester, J.; Valentin, D. Perception of Wine Quality According to Extrinsic Cues: The Case of Burgundy Wine Consumers. Food Qual. Prefer. 2013, 27, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veale, R.; Quester, P. Do Consumer Expectations Match Experience? Predicting the Influence of Price and Country of Origin on Perceptions of Product Quality. Int. Bus. Rev. 2009, 18, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oczkowski, E. The Impact of Different Names for a Wine Variety on Prices. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2018, 30, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, S.; Tuten, T. Message on a Bottle: The Wine Label’s Influence. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2011, 23, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidry, J.A.; Babin, B.J.; Graziano, W.G.; Schneider, W.J. Pride and Prejudice in the Evaluation of Wine? Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2009, 21, 298–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockshin, L.; Jarvis, W.; d’Hauteville, F.; Perrouty, J.P. Using Simulations from Discrete Choice Experiments to Measure Consumer Sensitivity to Brand, Region, Price, and Awards in Wine Choice. Food Qual. Prefer. 2006, 17, 166–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockshin, L.S.; Spawton, A.L.; Macintosh, G. Using Product, Brand and Purchasing Involvement for Retail Segmentation. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 1997, 4, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orme, B. Interpreting the results of conjoint analysis. In Getting Started with Conjoint Analysis: Strategies for Product Design and Pricing Research; Research Publishers LLC: Madison, WI, USA, 2019; pp. 77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, V.R. Applied Conjoint Analysis; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, K.; Hyde, J.; Bruwer, J. Usage Rate Segmentation: Enriching the US Wine Market Profile. Int. J. Wine Res. 2015, 7, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ittersum, K.; Candel, M.J.J.M.; Meulenberg, M.T.G. The Influence of the Image of a Product’s Region of Origin on Product Evaluation. J. Bus. Res. 2003, 56, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Butler, J.S. Expenditures on Wine in General and Local Wine in Particular: Marketing and Econometric Analysis. J. Agribus. 2018, 36, 109–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Trijp, H.C.M.; Steenkamp, J.-B.E.M. Consumers’ Variety Seeking Tendency with Respect to Foods: Measurement and Managerial Implications. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 1992, 19, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, J.E.; Atkin, T.; Thach, L.; Cuellar, S.S. Variety Seeking by Wine Consumers in the Southern States of the US. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2015, 27, 260–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, D.; Caruana, A. Consumer Wine Knowledge: Components and Segments. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2018, 30, 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, B.J.; Beck, J.T.; Price, J. Food as Ideology: Measurement and Validation of Locavorism. J. Consum. Res. 2018, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quester, P.G.; Smart, J. The Influence of Consumption Situation and Product Involvement over Consumers’ Use of Product Attribute. J. Consum. Mark. 1998, 15, 220–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Carrasco Martínez, L.; Brugarolas Mollá-Bauzá, M.; del Campo Gomis, F.J.; Martínez Poveda, Á. Influence of Purchase Place and Consumption Frequency over Quality Wine Preferences. Food Qual. Prefer. 2006, 17, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thach, L.; Olsen, J. Profiling the High Frequency Wine Consumer by Price Segmentation in the US Market. Wine Econ. Policy 2015, 4, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, K.M.; Todd, M.; Hopfer, H.; Centinari, M. Identifying Wine Consumers Interested in Environmentally Sustainable Production Practices. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res 2021. under review. [Google Scholar]

- Wine Market Council Wine Consumer Segmentation Slide Handbook. Available online: https://winemarketcouncil.com/wp-content/uploads/dlm_uploads/2019/09/2019_WMC_US_Wine_Consumer_Segmentation_Slide_Handbook_11-6-19.pptx (accessed on 7 August 2020).

- Thach, L.; Camillo, A. A Snapshot of the American Wine Consumer in 2018. Available online: https://www.winebusiness.com/news/?go=getArticle&dataId=207060 (accessed on 4 December 2020).

- Moore, W.L.; Gray-Lee, J.; Louviere, J.J. A Cross-Validity Comparison of Conjoint Analysis and Choice Models at Different Levels of Aggregation. Mark. Lett. 1998, 9, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau USDT 27 CFR § 4.21-The Standards of Identity. Available online: https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/27/4.21 (accessed on 7 August 2020).

- Atkin, T.S.; Newton, S.K. Consumer Awareness and Quality Perceptions: A Case for Sonoma County Wines. J. Wine Res. 2012, 23, 155–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.; Bruwer, J. Regional Brand Image and Perceived Wine Quality: The Consumer Perspective. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2007, 19, 276–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, D.; Mattison Thompson, F. The Effect of Wine Knowledge Type on Variety Seeking Behavior in Wine Purchasing. J. Wine Res. 2018, 29, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, S.L. The Influence of Gender on Wine Purchasing and Consumption. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2012, 24, 146–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factors | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Image |  (embellished) |  (simple) | -- |

| Font | Edwardian Script, Book Antiqua Bold (cursive) | Trebuchet, Myriad Variable Concept Light (sans-serif) | -- |

| Wine Type Text | Vidal blanc | White Wine | White Table Wine |

| Location Text | Lehigh Valley AVA (AVA) | Pennsylvania (state) | Proudly produced in Lehigh County, PA (county) |

| Category | Response Option | Counts | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 372 | 36.8% |

| Female | 638 | 63.1% | |

| Prefer not to answer/other | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Age | 21–25 | 43 | 4.2% |

| 26–30 | 76 | 7.5% | |

| 31–35 | 125 | 12.4% | |

| 36–40 | 141 | 13.9% | |

| 41–45 | 141 | 13.9% | |

| 46–50 | 120 | 11.9% | |

| 51–55 | 62 | 6.1% | |

| 56–60 | 72 | 7.1% | |

| 61–65 | 120 | 11.9% | |

| 66–70 | 111 | 11.0% | |

| State | New York | 324 | 32.0% |

| Pennsylvania | 206 | 20.4% | |

| New Jersey | 152 | 15.0% | |

| Ohio | 123 | 12.2% | |

| Virginia | 114 | 11.3% | |

| Maryland | 63 | 6.2% | |

| Washington, DC | 18 | 1.8% | |

| West Virginia | 11 | 1.1% | |

| Income | Less than USD 20,000 | 48 | 4.7% |

| USD 20,000–39,000 | 103 | 10.2% | |

| USD 40,000–59,000 | 139 | 13.7% | |

| USD 60,000–79,000 | 145 | 14.3% | |

| USD 80,000–99,000 | 141 | 13.9% | |

| Over USD 100,000 | 435 | 43.0% | |

| Wine Consumption | Daily | 71 | 7.0% |

| A few times per week | 328 | 32.4% | |

| About once per week | 208 | 20.6% | |

| A few times a month | 279 | 27.6% | |

| About once a month | 125 | 12.4% |

| Label | HB Model Estimate | Actual Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| White Wine, Pennsylvania | 23.4% | 18.9% |

| White Wine, County text | 30.6% | 33.3% |

| Vidal blanc, Pennsylvania | 16.4% | 20.0% |

| Vidal blanc, County text | 29.7% | 27.7% |

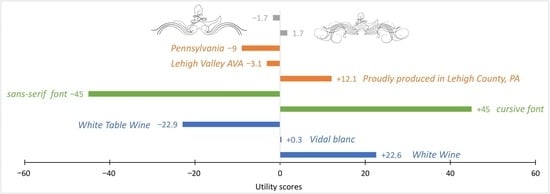

| Attribute | Importance | Levels | Utilities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wine Type | 45.4 | White Wine | 22.6 |

| Vidal blanc | 0.3 | ||

| White Table Wine | −22.9 | ||

| Font Type | 34.5 | Cursive | 45.0 |

| Sans-Serif | −45.0 | ||

| Location Text | 14.6 | County text: Proudly produced in Lehigh County, PA | 12.1 |

| AVA text: Lehigh Valley AVA | −3.1 | ||

| State text: Pennsylvania | −9.0 | ||

| Image | 5.5 | Flourished Image | 1.7 |

| Simple Image | −1.7 |

| Response | Percentage (Count) |

|---|---|

| The majority of the grapes are grown in the area designated on the label | 11% (116) |

| The wine is produced in accordance with winemaking laws designated by this region | 8% (77) |

| The wine has been certified by the American Viticultural Association for quality | 37% (370) |

| All of the grapes used to grow the wine are grown in the USA. | 5% (53) |

| I don’t know | 39% (395) |

| Count | White Wine | Vidal Blanc | White Table Wine | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | 535 | +30.7 | −10.0 | −20.6 |

| Maybe | 176 | +29.8 | −7.4 | −22.5 |

| Yes | 300 | +4.0 | +23.2 | −27.2 |

| Locavorism | Mean ± SD | Range | Counts | White Wine | Vidal Blanc | White Table Wine |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 51.2 ± 8.4 | 15–75 | 1011 | 22.6 | 0.3 | −22.9 |

| Low | 42.2 ± 4.9 | 15–47 | 343 | 25.7 | 1.5 | −27.2 |

| Medium | 51.4 ± 2.2 | 48–55 | 343 | 22.6 | 0.8 | −23.4 |

| High | 60.5 ± 4.2 | 56–75 | 325 | 19.4 | −1.5 | −17.9 |

| Variety Seeking (VARSEEK) | ||||||

| Overall | 29.6 ± 5.2 | 8–40 | 1011 | 22.6 | 0.3 | −22.9 |

| Low | 24.2 ± 3.7 | 8–28 | 369 | 33.6 | −18.1 | −15.5 |

| Medium | 30.5 ± 1.1 | 29–32 | 363 | 20.1 | 7.0 | −27.1 |

| High | 35.6 ± 2.2 | 33–40 | 279 | 11.3 | 16.0 | −27.2 |

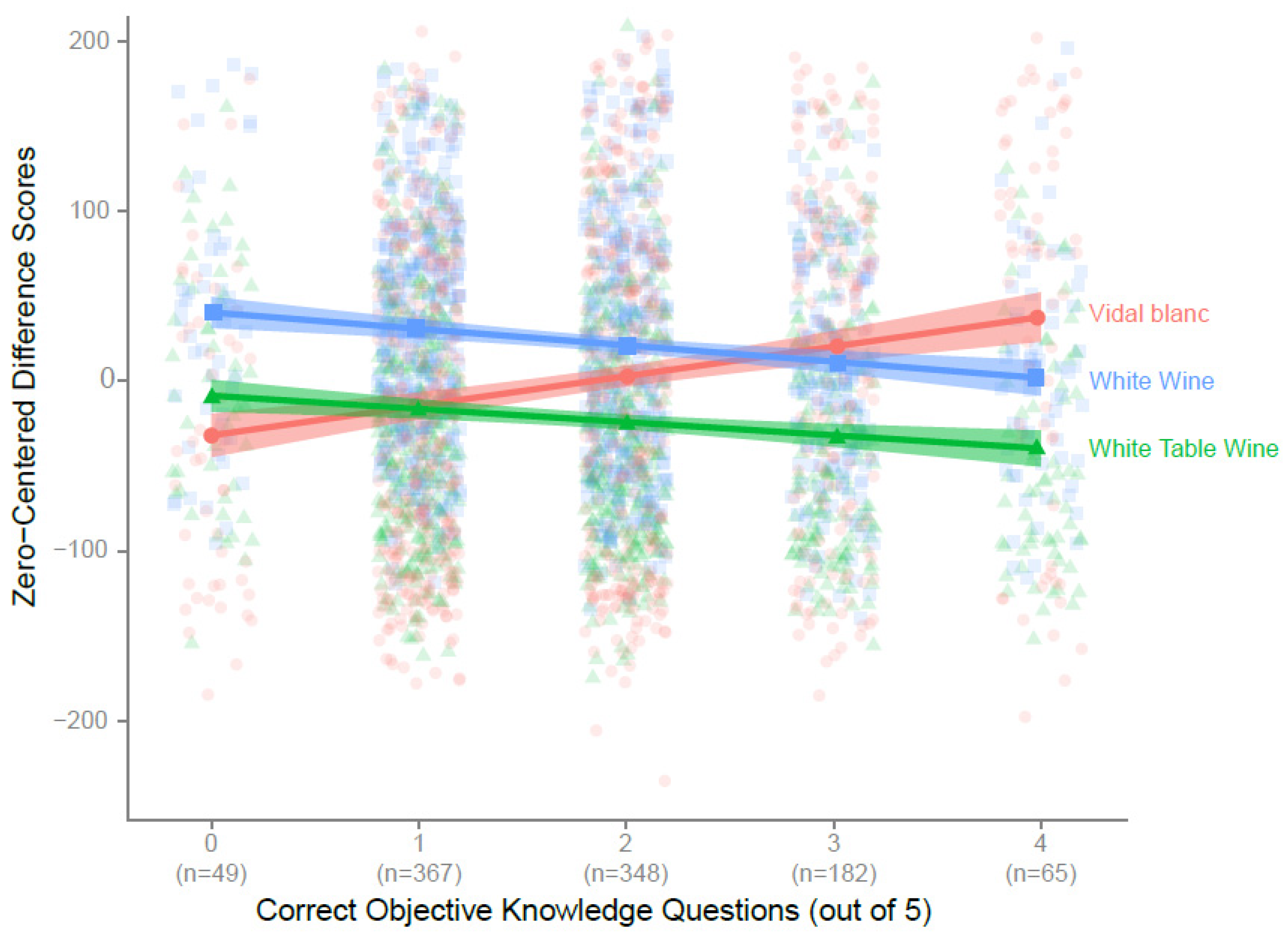

| Subjective Knowledge | ||||||

| Overall | 35.8 ± 10.4 | 9–63 | 1011 | 22.6 | 0.3 | −22.9 |

| Low | 24.8 ± 5.8 | 9–32 | 366 | 29.7 | −11.7 | −18.0 |

| Medium | 36.9 ± 2.3 | 33–40 | 320 | 26.9 | −1.2 | −25.7 |

| High | 47.1 ± 5.5 | 41–63 | 325 | 10.4 | 15.3 | −25.7 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Todd, M.J.; Kelley, K.M.; Hopfer, H. USA Mid-Atlantic Consumer Preferences for Front Label Attributes for Local Wine. Beverages 2021, 7, 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages7020022

Todd MJ, Kelley KM, Hopfer H. USA Mid-Atlantic Consumer Preferences for Front Label Attributes for Local Wine. Beverages. 2021; 7(2):22. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages7020022

Chicago/Turabian StyleTodd, Marielle J., Kathleen M. Kelley, and Helene Hopfer. 2021. "USA Mid-Atlantic Consumer Preferences for Front Label Attributes for Local Wine" Beverages 7, no. 2: 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages7020022

APA StyleTodd, M. J., Kelley, K. M., & Hopfer, H. (2021). USA Mid-Atlantic Consumer Preferences for Front Label Attributes for Local Wine. Beverages, 7(2), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages7020022